Abstract

Objectives

To describe the prevalence of respiratory pathogens in tuberculosis (TB) patients and in their household contact controls, and to determine the clinical significance of respiratory pathogens in TB patients.

Methods

We studied 489 smear-positive adult TB patients and 305 household contact controls without TB with nasopharyngeal swab samples within an ongoing prospective cohort study in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, between 2013 and 2015. We used multiplex real-time PCR to detect 16 respiratory viruses and seven bacterial pathogens from nasopharyngeal swabs.

Results

The median age of the study participants was 33 years; 61% (484/794) were men, and 21% (168/794) were HIV-positive. TB patients had a higher prevalence of HIV (28.6%; 140/489) than controls (9.2%; 28/305). Overall prevalence of respiratory viral pathogens was 20.4% (160/794; 95%CI 17.7–23.3%) and of bacterial pathogens 38.2% (303/794; 95%CI 34.9–41.6%). TB patients and controls did not differ in the prevalence of respiratory viruses (Odds Ratio [OR] 1.00, 95%CI 0.71–1.44), but respiratory bacteria were less frequently detected in TB patients (OR 0.70, 95%CI 0.53–0.94). TB patients with both respiratory viruses and respiratory bacteria were likely to have more severe disease (adjusted OR [aOR] 1.6, 95%CI 1.1–2.4; p 0.011). TB patients with respiratory viruses tended to have more frequent lung cavitations (aOR 1.6, 95%CI 0.93–2.7; p 0.089).

Conclusions

Respiratory viruses are common for both TB patients and household controls. TB patients may present with more severe TB disease, particularly when they are co-infected with both bacteria and viruses.

Keywords: Haemophilus influenzae, Human rhinovirus virus, Influenza, Respiratory bacteria, Respiratory viruses, Tanzania, Tuberculosis

Introduction

Tuberculosis (TB) caused by the bacterium Mycobacterium tuberculosis affected an estimated 10.4 million new cases and caused 1.7 million deaths in 2016, making TB the leading global cause of death from an infectious disease [1]. Influenza pandemics have selectively caused higher mortality among persons with TB compared to the general population [2], [3]. For instance, the 1918 influenza pandemic brought about a sharp decline in TB burden, possibly because of the higher mortality among TB patients co-infected with influenza viruses [3], [4].

In sub-Saharan Africa, HIV has been the most important risk factor driving the TB epidemic in recent decades [5]. The efforts towards understanding other risk factors in TB—such as respiratory viruses, helminths [6], and bacteria [7]—are becoming increasingly important [8]. Evidence from experimental mouse models suggests that respiratory viruses such as influenza viruses may play a pathogenic role in individuals with tuberculous disease by negatively affecting immunity against M. tuberculosis [9]. The effect of respiratory viruses on TB may mimic the development of bacterial pneumonia immediately after an infection with respiratory viruses [10]. Studies of the lung microbiota (the community of microorganisms in the airways), which have focused on respiratory bacterial populations, suggest that there are differences in respiratory bacterial species populations among patients with and without TB, among new and recurrent TB patients, as well as among those in whom TB treatment has failed [7].

The differences in airway microorganism populations could indicate that respiratory pathogens can be involved in TB pathogenesis [11]. However, little is known about the prevalence of respiratory pathogens, whether viral or bacterial, and their role in clinical presentation in TB. We therefore studied the prevalence of respiratory pathogens in TB patients and household contact controls, and assessed the associations between both respiratory viruses and bacterial pathogens and the clinical presentation of TB patients who were prospectively recruited in an area of Dar es Salaam (Tanzania) with a high TB burden.

Methods

Study setting and study population

This is a prospective cohort study conducted in the densely populated Temeke district of Dar es Salaam, Tanzania; it is a study within a previously described ongoing prospective cohort study of TB patients and household contact controls in Dar es Salaam (TB-DAR) [6]. Between November 2013 and October 2015, we recruited smear-positive TB patients diagnosed at Temeke district hospital and household contact controls who lived in the same household as the index TB cases [6].

Assuming (a) a prevalence of respiratory viruses of 25% in TB patients and of 12.5% in household contact controls [12], based on the prevalence of respiratory viruses in similar settings, and assuming that respiratory viruses are more frequent in TB patients than in controls, (b) a cluster correlation of 0.2, and (c) a non-participation rate of 20%, we estimated that 175 case–control pairs would provide 85% power to observe a statistically significant difference in the prevalence at the 5% level of significance.

Study procedures

At the time of recruitment of study participants, we collected a single sample of nasopharyngeal swabs from TB patients and controls using flexible nasopharyngeal flocked swabs (Copan Diagnostics, CA, USA) [13]. For TB patients, the nasopharyngeal swabs were taken immediately after diagnosis of TB and prior to initiation of anti-TB treatment. The nasopharyngeal swab samples were then added to 1-mL eNAT tubes for transportation at temperatures between 2° and 8°C to the Ifakara Health Institute (IHI) research laboratory at Bagamoyo where they were stored at –80°C pending analysis.

Laboratory investigations

Detection of respiratory pathogens by multiplex PCR

We used the validated multiplex real-time PCRs from Seegene (www.seegene.com/) for detection of a broad panel of respiratory viral and bacterial pathogens in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions, as previously published [14]. The nasopharyngeal swab samples were also analysed using Anyplex II RV16 simultaneously which detects 16 respiratory viruses, and the Allplex Respiratory Panel 4 assay which detects seven respiratory bacterial pathogens (Table S1). Sample processing and analysis to detect respiratory pathogens were all done at the IHI research laboratory in accordance with the manufacturer's instructions and Standard Operating Procedures (SOP).

Other laboratory procedures

TB confirmation was by positive Löwenstein–Jensen (LJ) solid media mycobacterial culture (done at the IHI Research laboratory in Bagamoyo). We ruled out TB in controls with both a negative Gene Xpert MTB/RIF result and no mycobacterial growth in LJ solid media culture. HIV testing for TB patients and controls was done as per Tanzania HIV testing algorithms using an Alere Determine HIV (Alere, USA) and a Uni-Gold HIV (Trinity Biotech; Wicklow, Ireland) confirmatory test rapid tests [15]. CD4+ T cells and full blood-cell counts were obtained as previously described [6].

Data collection and definitions

Clinical severity of TB was graded as per published clinical TB score [16], but modified to a set of 12 TB score parameters instead of 13, since tachycardia was not systematically measured as previously noted [6]. Diagnosis delay was defined as a cough duration of ≥3 weeks as previously published from the same cohort study [17].

Data were captured using electronic case report forms developed from the open source data collection software Open Data Kit (ODK, https://opendatakit.org/) on Android PC tablets, and data were then managed using the eManagement tool ‘odk_planner’ as published previously [18].

Statistical analysis

We compared the baseline characteristics of TB patients and household contact controls using the McNemar test, paired t-test, or Wilcoxon signed rank test, as appropriate. We estimated the prevalence of any respiratory viruses and bacteria using logistic regression models adjusting for clustering at the household level. We used mixed-effects logistic regression models with random household intercepts to assess the risk factors associated with detection of respiratory pathogens in TB patients and controls. The differences in the mean Ct values of respiratory bacteria detected (as a relative measure of the bacterial load) between TB patients and controls were assessed using mixed-effect linear regression models. Logistic regression models adjusting for age, sex, and HIV infection were used to assess the associations between respiratory pathogens and clinical presentations of TB at the time of recruitment among TB patients, with the following outcome variables: severe TB score (score of ≥6) versus mild (score of 1–5), high sputum bacterial load (sputum AFB smear microscopy of ≥2+) versus low bacterial load, and presence versus absence of lung infiltrations and cavitations (chest x-ray findings). Associations were expressed as crude odds ratios (ORs) and adjusted ORs (aORs) with their corresponding 95% confidence intervals (95%CIs). All analyses were performed in Stata version 14.0 (Stata Corp, College Station, Texas, USA).

Ethics approval

The study was approved by the IHI Institutional Review Board (IHI/IRB/No: 04-2015) and the Medical Research Coordinating Committee of the National Institute of Medical Research (NIMR/HQ/R.8c/Vol.I/357) in Tanzania, as well as by the Ethics Committee of the Canton of Basel in Switzerland (EKNZ UBE-15/42). All study participants gave written informed consent. TB patients were managed as per National TB and Leprosy Programme treatment guidelines [19]. Treatment and care for HIV-positive individuals were as per Tanzania National HIV/AIDS treatment guideline [15].

Results

Characteristics of study participants

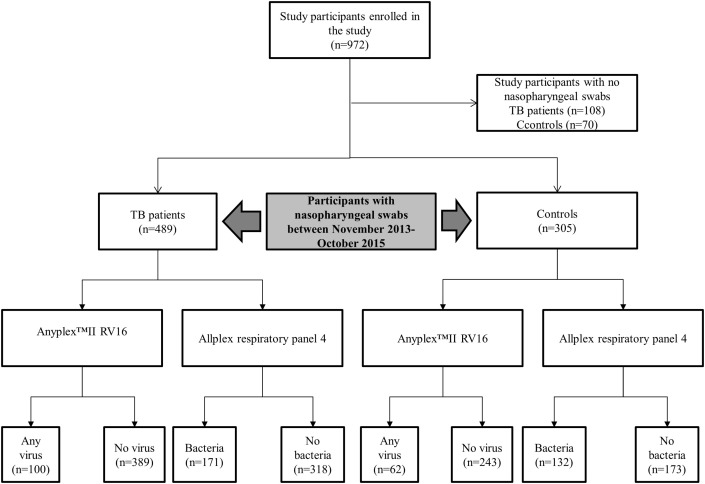

Between November 2013 and October 2015, 972 study participants were enrolled in the TB-Dar study. A total of 794 study participants (81.6%; 794/972) had a nasopharyngeal swab taken, of whom 489 were TB patients and 305 were household contact controls (Fig. 1 ). The overall median age was 33 years (interquartile range (IQR) 26.1–41.2 years), and 61% (484/794) were men. The overall HIV prevalence was 21.2% (168/794; 95%CI 18.4–24.1%); 140 TB patients (28.6%; 140/489) and 28 controls (9.2%; 28/305) were HIV-positive (Table 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Flow diagram for participants enrolled in the study.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of 489 tuberculosis (TB) patients and 305 household contact controls without TB in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania

| Characteristics n (%) | All |

TB patients |

Controls |

p |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 794) | (n = 489) | (n = 305) | ||

| Age (years), median (IQR) | 33.0 (26.1–41.2) | 33.0 (27.0–40.0) | 32.0 (25.7–42.4) | 0.7 |

| Age groups (years) | 0.096 | |||

| <25 | 153 (19.3) | 82 (16.8) | 71 (23.3) | |

| 25–34 | 290 (36.5) | 188 (38.4) | 102 (33.4) | |

| 35–44 | 205 (25.8) | 132 (27) | 73 (23.9) | |

| ≥45 | 146 (18.4) | 87 (17.8) | 59 (19.3) | |

| Male, sex | 484 (61.0) | 336 (68.7) | 148 (48.5) | <0.001 |

| HIV-positive | 168 (21.2) | 140 (28.6) | 28 (9.2) | <0.001 |

| Education level | 0.19 | |||

| No/primary | 285 (35.9) | 168 (34.4) | 117 (38.4) | |

| Secondary/University | 509 (64.1) | 321 (65.6) | 188 (61.6) | |

| Occupation | 0.25 | |||

| Employed | 509 (64.1) | 321 (65.6) | 188 (61.6) | |

| Current smoker | 0.053 | |||

| Yes | 104 (13.1) | 73 (14.9) | 31 (10.2) | |

| People in the household | 0.22 | |||

| >3 people | 204 (25.7) | 133 (27.2) | 71 (23.3) | |

| Weight (kg), median (IQR) | 54.0 (48.0–61.0) | 51.0 (45.5–57.0) | 59.0 (53.0–67.0) | <0.001 |

| BMI (kg/m2), median(IQR) | 20.1 (17.5–23.4) | 18.3 (16.5–20.4) | 24.0 (21.7–27.9) | <0.001 |

| BMI categories (kg/m2) | <0.001 | |||

| Normal/obese ≥18 | 517 (65.1) | 227 (46.4) | 290 (95.1) | |

| Underweight <18 | 277 (34.9) | 262 (53.6) | 15 (4.9) | |

| Body fat percentage (%) | 9.92 (7.5–14.4) | 9.41 (6.8–13.5) | 11 (8.5–15.8) | <0.001 |

| Hb level (g/dL), median (IQR) | 12.1 (10.4–13.3) | 11.4 (9.9–12.7) | 12.8 (11.5–14.2) | <0.001 |

| TB categories | ||||

| New | 477 (97.5) | 477 (97.5) | NA | NA |

| Retreatment | 12 (2.5) | 12 (2.5) | NA | |

BMI, body mass index; IQR, interquartile range; Hb, haemoglobin; HIV, human immunodeficiency virus; NA, not applicable.

Prevalence of respiratory viral and bacterial pathogens

The frequency distributions of the respiratory viruses detected from study participants are summarized in Table 2 . The overall prevalence of any respiratory virus among TB patients and controls was 20.4% (161/794; 95%CI 17.7–23.3%), and the odds of detecting any virus was the same in TB patients and controls (OR 1.00, 95%CI 0.71–1.44; p 0.98). The most common respiratory species detected was human rhinovirus A/B/C (HRV), which was found in 9.3% (74/794) of the study participants, followed by influenza A in 3.1% (25/794) and respiratory syncytial virus A (RSVA) in 1.9% (15/794). We detected only minor differences between TB patients and household contact controls in the prevalence (Table 2) and the semiquantitative detection (Fig. S1) of respiratory viruses. We detected respiratory viruses more frequently during the months of March and April, and October to November (Fig. S2).

Table 2.

Frequencies of virus detection in the tuberculosis (TB) patients and household contact controls in Tanzania, and odds ratios of detection in TB patients compared to controls

| Detection of viral species | All |

TB patients |

Controls |

OR (95%CI) | p |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| (n = 794) | (n = 489) | (n = 305) | |||

| Any respiratory virus | 162 (20.4) | 100 (20.4) | 62 (20.3) | 1.00 (0.71–1.44) | 0.98 |

| Respiratory viral species | |||||

| Human rhinovirus A/B/C | 74 (9.3) | 42 (8.6) | 32 (10.5) | 0.80 (0.49–1.30) | 0.37 |

| Influenza A | 25 (3.1) | 15 (3.1) | 10 (3.3) | 0.93 (0.41–2.11) | 0.87 |

| RSVA | 15 (1.9) | 12 (2.5) | 3 (1.0) | 2.53 (0.71–9.05) | 0.15 |

| Adenovirus | 14 (1.8) | 9 (1.8) | 5 (1.6) | 1.13 (0.37–3.39) | 0.83 |

| RSVB | 12 (1.5) | 9 (1.8) | 3 (1.0) | 1.89 (0.51–7.03) | 0.34 |

| Parainfluenza virus 4 | 9 (1.1) | 4 (0.8) | 5 (1.6) | 0.49 (0.13–1.86) | 0.3 |

| Coronavirus OC43 | 9 (1.1) | 5 (1.0) | 4 (1.3) | 0.78 (0.21–2.92) | 0.71 |

| Coronavirus NL63 | 4 (0.5) | 3 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | 1.87 (0.19–18.12) | 0.59 |

| Enterovirus | 4 (0.5) | 4 (0.8) | 0 (0) | NA | |

| Bocavirus 1/2/3/4 | 3 (0.4) | 2 (0.4) | 1 (0.3) | 1.24 (0.11–13.83) | 0.86 |

| Parainfluenza virus 2 | 3 (0.4) | 1 (0.2) | 2 (0.7) | 0.31 (0.03–3.44) | 0.34 |

| Influenza B | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.2) | 1 (0.3) | 0.62 (0.04–10.0) | 0.74 |

| Parainfluenza virus 3 | 2 (0.3) | 2 (0.4) | 0 (0) | 0.90 (0.41–1.97) | 0.80 |

| Metapneumovirus | 1 (0.1) | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0) | NA | |

| Coronavirus 229E | 1 (0.1) | 0 (0) | 1 (0.3) | NA | |

| Groups of detected viruses | |||||

| Influenza A/B | 27 (3.4) | 16 (3.3) | 11 (3.6) | 0.90 (0.41–1.97) | 0.80 |

| Influenza-like (influenza and parainfluenza viruses) | 40 (5.0) | 23 (4.7) | 17 (5.6) | 0.84 (0.44–1.60) | 0.59 |

| Coronaviruses | 14 (1.8) | 8 (1.6) | 6 (2.0) | 0.83 (0.28–2.41) | 0.73 |

| Parainfluenza 2/3/4 | 13 (1.6) | 7 (1.4) | 6 (2.0) | 0.72 (0.24–2.17) | 0.56 |

| RSV | 25 (3.1) | 19 (3.9) | 6 (2.0) | 2.01 (0.80–5.10) | 0.14 |

| Groups according to the number of detected viral species | 0.96 | ||||

| One species | 145 (18.3) | 89 (18.2) | 56 (18.4) | 0.99 (0.69–1.44) | |

| ≥2 species | 17 (2.1) | 11 (2.2) | 6 (2.0) | 1.15 (0.42–3.13) | |

| Respiratory bacterial pathogens | |||||

| Any bacterial species | 303 (38.2) | 171 (35.0) | 132 (43.3) | 0.70 (0.53–0.94) | 0.019 |

| Respiratory bacterial species | |||||

| Haemophilus influenzae | 207 (26.1) | 110 (22.5) | 97 (31.8) | 0.62 (0.45–0.86) | 0.004 |

| Streptococcus pneumoniae | 171 (21.5) | 99 (20.2) | 72 (23.6) | 0.82 (0.58–1.16) | 0.26 |

| Legionella pneumophila | 12 (1.5) | 9 (1.8) | 3 (1.0) | 1.89 (0.51–7.03) | 0.34 |

| Bordetella parapertussis | 4 (0.5) | 3 (0.6) | 1 (0.3) | 1.88 (0.19–18.12) | 0.59 |

| Mycoplasma pneumoniae | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | N/A |

| Bordetella pertussis | 5 (0.6) | 4 (0.8) | 1 (0.3) | 2.51 (0.28–22.54) | 0.41 |

| Chlamydophila pneumoniae | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | NA | NA |

| Groups according to the number of detected bacterial species | 0.062 | ||||

| One specie | 209 (26.3) | 119 (24.3) | 90 (29.5) | 0.72 (0.52–1.00) | |

| ≥2 species | 94 (11.8) | 52 (10.6) | 42 (13.8) | 0.67 (0.43–1.05) | |

OR, odds ratio; 95%CI, 95% confidence interval; NA, not applicable.

ORs and p calculated from mixed-effects logistic regression models with random household intercepts.

The prevalence of any bacterial pathogen among study participants was 38.2% (303/794; 95%CI 34.9–41.6%, Table 2). Respiratory bacteria were less likely be detected in TB patients than in controls (OR 0.70, 95%CI 0.53–0.94; p 0.02). The most common bacterial species detected were Haemophila influenzae, found in 26.1% of study participants (207/794), followed by Streptococcus pneumoniae in 21.5% (171/794). TB patients were less likely than household contact controls to have H. influenzae (OR 0.62, 95%CI 0.45–0.86; p 0.004). The mean values of cycle threshold for TB patients were slightly higher (indicating a smaller bacterial load) than those of household contact controls (greater bacterial load), but this did not reach conventional levels of statistical significance (Fig. S3). There were 12 TB patients on a retreatment drug regimen, and in ten of them (83.3%) both respiratory bacteria and respiratory viruses were detected.

The factors associated with detection of respiratory viruses include smoking and households containing three or more people. Men were the more likely to have respiratory bacteria (see Table S3).

Associations between respiratory pathogens and clinical presentation

TB patients with both viral and bacterial pathogens had significantly more severe TB disease than TB-only patients (aOR 1.64, 95%CI 1.11–2.37; p 0.01; Table 3 ). Bacterial respiratory pathogens were not significantly associated with the clinical presentation of TB patients at TB diagnosis. Detection of respiratory pathogens was not associated with including diagnostic delay (defined as duration of symptoms of 3 weeks or more) (see Table 3). No association was found between detection of respiratory pathogens and chest x-ray findings among TB patients (Table 4 ). In addition, the detection of respiratory pathogens was similar for HIV-positive and HIV-negative TB patients (Tables S2 and S3).

Table 3.

Clinical significance of respiratory pathogens among tuberculosis (TB) patients at the time of TB diagnosis

| Respiratory pathogens detected | Severe TB scorea |

High sputum bacterial loadb |

Lung cavitationc |

Lung infiltrationsc |

Diagnostic delayd |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| aOR (95%CI) | p | aOR (95%CI) | p | aOR (95%CI) | p | aOR (95%CI) | p | aOR (95%CI) | p | |

| Respiratory viruses | ||||||||||

| Any viral species | 0.072 | 0.69 | 0.089 | 0.88 | 0.46 | |||||

| Yes | 1.52 (0.96–2.4) | 1.10 (0.69–1.76) | 1.58 (0.93–2.68) | 1.04 (0.60–1.83) | 0.80 (0.45–1.43) | |||||

| Respiratory bacteria | ||||||||||

| Any bacterial species | 0.17 | 0.89 | 0.65 | 0.85 | 0.77 | |||||

| Yes | 1.32 (0.89–1.94) | 1.03 (0.69–1.53) | 0.90 (0.56–1.44) | 0.95 (0.58–1.56) | 1.07 (0.67–1.71) | |||||

| Combined detection of viral and bacterial species | 0.01 | 0.95 | 0.7 | 0.71 | 0.53 | |||||

| Yes | 1.64 (1.11–2.37) | 1.00 (0.68–1.46) | 1.09 (0.70–1.71) | 0.92 (0.57–1.46) | 0.87 (0.55–1.37) | |||||

aOR, adjusted odds ratios; 95% CI, 95% confidence interval

Logistic regression model adjusted for age-group, sex, and HIV infection.

Severe TB score (6 to 12) compared to mild TB score (1 to 5).

High sputum bacterial load (≥2+ according to qualitative AFB smear microscopy grading) compared to low load (scanty up to 1+).

As determined by chest x-ray features.

Diagnostic delay defined as defined symptoms duration of ≥3 weeks.

Table 4.

Chest x-ray findings of tuberculosis (TB) patients with and without any respiratory pathogens (viruses and bacteria)

| Chest x-ray findings | Total |

TB and respiratory pathogen(s) |

TB only |

pa |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||

| Any respiratory viruses | ||||

| Infiltrates | 236 (64) | 51 (64.6) | 185 (63.8) | 0.90 |

| Cavitations | 125 (33.9) | 33 (41.8) | 92 (31.7) | 0.09 |

| Pleural effusion | 44 (11.9) | 7 (8.9) | 37 (12.8) | 0.34 |

| Lymph nodes | 31 (8.4) | 6 (7.6) | 25 (8.6) | 0.77 |

| Micronodules | 22 (6) | 5 (6.3) | 17 (5.9) | 0.88 |

| Macronodules | 5 (1.4) | 1 (1.3) | 4 (1.4) | 0.94 |

| Any respiratory bacteria | ||||

| Infiltrations | 236 (64) | 78 (63.9) | 158 (64) | 0.99 |

| Cavitations | 125 (33.9) | 40 (32.8) | 85 (34.4) | 0.76 |

| Pleural effusion | 44 (11.9) | 15 (12.3) | 29 (11.7) | 0.88 |

| Lymph nodes | 31 (8.4) | 11 (9) | 20 (8.1) | 0.77 |

| Micronodules | 22 (6) | 9 (7.4) | 13 (5.3) | 0.42 |

| Macronodules | 5 (1.4) | 1 (0.8) | 4 (1.6) | 0.53 |

p calculated from χ-square test.

Discussion

Both respiratory viruses and respiratory bacteria are commonly detected in a high-TB-incidence setting, and the prevalence of respiratory bacteria was lower in TB patients than in household contact controls. Detection of respiratory viruses and respiratory bacteria in TB patients was associated with more severe disease.

The prevalence of any respiratory viruses was the same (20%) for both TB patients and controls without TB. Similar prevalence of respiratory viruses in controls as compared to TB patients could be due to controls being more active than TB patients, hence having increased social contacts. The prevalence shown in our study was lower than that reported in an Indonesian study of influenza viruses that observed respective prevalences of around 46% and 41% for TB patients and controls, respectively [20]. The difference in the prevalence of influenza in that study compared to ours could be due to the different study region (Asia versus sub-Saharan Africa) and the use of different diagnostic methods (immunological assay versus molecular detection). We detected respiratory viruses from nasopharyngeal swabs using a highly sensitive and specific molecular technique [21], whereas the study from Indonesia [20] measured influenza virus antibody titres which also detect patients with previous exposure to influenza viruses. The influenza antibody titres were higher in TB patients than in controls, suggesting recent viral infection before the clinical manifestations of TB [20].

We did not find any evidence for an association between HIV infection and detection of respiratory pathogens. In line with our results, a household study on respiratory illness surveillance and HIV testing in Kenya [22] did not find any association between HIV and influenza viruses. However, household contacts of the HIV-infected influenza index cases were twice as likely to develop a secondary case of influenza-like illness [22].

We also found that the presence of both viruses and bacteria could potentially alter the clinical course of TB, and present with a more severe disease as measured by the previously validated clinical TB score [16]. Direct evidence of clinical effects of respiratory viruses on TB have only been demonstrated in experimental mouse models that have exhibited higher mycobacterial loads in the lungs and increased lung inflammation [9]. The immunological pathway responsible for more severe clinical presentation in TB patients may occur either via the type I interferon-receptor-dependent pathway [9] or via decreased MHC II expression on dendritic cells [23], which may result in poor clearance of M. tuberculosis from the lungs.

We found smoking and living in a household with three or more persons to be risk factors for respiratory viruses. Smoking has been shown, at least in animal models, to inhibit the pulmonary T-cell response to influenza viruses, thus increasing susceptibility to infection [24], and respiratory viruses were more likely to be detected in children living with a smoker [25]. In addition, overcrowding—which we defined as three or more persons in a household—is a common risk factor for most airborne pathogens such as M. tuberculosis [26] and respiratory viruses [22].

The prevalence of bacterial respiratory pathogens in our study was lower in TB patients than in household contact controls, suggesting interactions between M. tuberculosis and the bacterial populations in the airways. Overall respiratory bacterial load was smaller in TB patients than in controls. This is similar to findings from a microbiota study which reported smaller bacterial loads in TB patients than in controls [27]. The authors argue that the initial phase of M. tuberculosis invasion in the lungs may prompt an immune response that could also reduce the commensal flora in the lower respiratory tract [27]. Interestingly, in a mouse model, M. tuberculosis infection in the lungs appeared also to have an effect on the gut microbiota, which is part of the collective human microbiota [28]. These findings consistently suggest interactions between M. tuberculosis and the communities of microorganisms, and a role for these interactions in TB pathogenesis.

We believe that this is the first study to have looked systematically at a wide range of viral and bacterial species in TB patients and controls, and using sensitive molecular techniques and clinical specimens from a well-defined compartment of the airways. A particular strength of the study is that potentially confounding and unmeasured risk factors were minimized by studying patients and controls who lived in the same households. A limitation of the study is its undifferentiated attention to respiratory viruses because of small numbers which precluded assessment of the clinical effects of individual viruses. However, we presume that all respiratory viruses have similar levels of immunomodulation, and thus we could combine all respiratory viruses together.

In conclusion, respiratory pathogens are common in the high-TB setting of Tanzania for both TB patients and household contact controls without TB. However, respiratory bacterial species were more frequently detected in household contact controls than in TB patients. Our findings suggest that TB patients co-infected with both respiratory viruses and respiratory bacteria have severe TB disease. Further research should focus on the pathogenic role of respiratory pathogens in high-TB-incidence settings and their effects on clinical and treatment outcomes.

Transparency declaration

All authors have declared no conflicts of interest. This work was supported by the Rudolf Geigy Foundation, Basel, Switzerland (to LF and FM), and a personal grant by the ‘Amt für Ausbildungsbeiträge’, Basel, Switzerland (to FM).

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank all the study participants whose data were used in this study. We are most grateful for the assistance and support of the District Medical Officer, Medical Officer in charge, hospital staff, the district TB coordinators in the Temeke district, Dar es Salaam, Tanzania, and the National Tuberculosis and Leprosy Programme. We also thank the Ifakara Health Institute study team working at the Temeke district hospital for recruiting study participants.

Editor: M. Paul

Footnotes

Preliminary findings of this study were presented at (i) the 9th European Congress on Tropical Medicine and International Health (ECTMIH), 6–10 September 2015, Basel, Switzerland, and (ii) the 47th Union World Conference on Lung Health, 26–29 October 2016, Liverpool, UK.

Supplementary data related to this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cmi.2018.03.019.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the supplementary data related to this article:

References

- 1.WHO . World Health Organization; Geneva, Switzerland: 2017. Global tuberculosis report. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noymer A. Testing the influenza–tuberculosis selective mortality hypothesis with Union Army data. Soc Sci Med. 2009;68:1599–1608. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.02.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zürcher K., Zwahlen M., Ballif M., Rieder H.L., Egger M., Fenner L. Influenza pandemics and tuberculosis mortality in 1889 and 1918: analysis of historical data from Switzerland. PLoS One. 2016;11:e0162575. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Noymer A. The 1918 influenza pandemic hastened the decline of tuberculosis in the United States: an age, period, cohort analysis. Vaccine. 2011;29:B38–B41. doi: 10.1016/j.vaccine.2011.02.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.WHO . 2016. Global tuberculosis report; p. 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mhimbira F., Hella J., Said K., Kamwela L., Sasamalo M., Maroa T. Prevalence and clinical relevance of helminth co-infections among tuberculosis patients in urban Tanzania. PLoS Negl Trop Dis. 2017;11:e0005342. doi: 10.1371/journal.pntd.0005342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu J., Liu W., He L., Huang F., Chen J., Cui P. Sputum microbiota associated with new, recurrent and treatment failure tuberculosis. PLoS One. 2013;8:e83445. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0083445. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Marais B.J., Lönnroth K., Lawn S.D., Migliori G.B., Mwaba P., Glaziou P. Tuberculosis comorbidity with communicable and non-communicable diseases: integrating health services and control efforts. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;3 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70015-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Redford P.S., Mayer-Barber K.D., McNab F.W., Stavropoulos E., Wack A., Sher A. Influenza A virus impairs control of Mycobacterium tuberculosis coinfection through a type I interferon receptor-dependent pathway. J Infect Dis. 2013 doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit424. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rohde G., Wiethege A., Borg I., Kauth M., Bauer T.T., Gillissen A. Respiratory viruses in exacerbations of chronic obstructive pulmonary disease requiring hospitalisation: a case–control study. Thorax. 2003;58:37–42. doi: 10.1136/thorax.58.1.37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wood M.R., Yu E.A., Mehta S. The human microbiome in the fight against tuberculosis. Am J Trop Med Hyg. 2017;96:1274–1284. doi: 10.4269/ajtmh.16-0581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Bigogo G.M., Breiman R.F., Feikin D.R., Audi A.O., Aura B., Cosmas L. Epidemiology of respiratory syncytial virus infection in rural and urban Kenya. J Infect Dis. 2013;208:S207–S216. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.FLOQSwabsTM: COPAN’s patented flocked swabs. Copan Diagn Inc n.d. http://www.copanusa.com/products/collection-transport/floqswabs-flocked-swabs/ (accessed June 5, 2017).

- 14.Cho C.H., Chulten B., Lee C.K., Nam M.H., Yoon S.Y., Lim C.S. Evaluation of a novel real-time RT-PCR using TOCE technology compared with culture and Seeplex RV15 for simultaneous detection of respiratory viruses. J Clin Virol. 2013;57:338–342. doi: 10.1016/j.jcv.2013.04.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.NACP . 5th ed. Ministry of Health and Social Welfare; Dar es Salaam: 2015. National guidelines for the management of HIV and AIDS. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wejse C., Gustafson P., Nielsen J., Gomes V.F., Aaby P., Andersen P.L. TB score: signs and symptoms from tuberculosis patients in a low-resource setting have predictive value and may be used to assess clinical course. Scand J Infect Dis. 2008;40:111–120. doi: 10.1080/00365540701558698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Said K., Hella J., Mhalu G., Chiryankubi M., Masika E., Maroa T. Diagnostic delay and associated factors among patients with pulmonary tuberculosis in Dar es Salaam, Tanzania. Infect Dis Poverty. 2017;6:64. doi: 10.1186/s40249-017-0276-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Steiner A., Hella J., Grüninger S., Mhalu G., Mhimbira F., Cercamondi C.I. Managing research and surveillance projects in real-time with a novel open-source eManagement tool designed for under-resourced countries. J Am Med Inform Assoc. 2016:ocv185. doi: 10.1093/jamia/ocv185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.NTLP, MoHSW . 6th ed. Ministry of Health and Social Welfare; Dar es Salaam: 2013. Manual for the management of tuberculosis and leprosy. [Google Scholar]

- 20.de Paus R.A., van Crevel R., van Beek R., Sahiratmadja E., Alisjahbana B., Marzuki S. The influence of influenza virus infections on the development of tuberculosis. Tuberculosis. 2013;93:338–342. doi: 10.1016/j.tube.2013.02.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Niang M.N., Diop N.S., Fall A., Kiori D.E., Sarr F.D., Sy S. Respiratory viruses in patients with influenza-like illness in Senegal: focus on human respiratory adenoviruses. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0174287. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0174287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Judd M.C., Emukule G.O., Njuguna H., McMorrow M.L., Arunga G.O., Katz M.A. The role of HIV in the household introduction and transmission of influenza in an urban slum, Nairobi, Kenya, 2008–2011. J Infect Dis. 2015;212:740–744. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Flórido M., Grima M., Gillis C.M., Xia Y., Turner S.J., Triccas J. Influenza A virus infection impairs mycobacteria-specific T cell responses and mycobacterial clearance in the lung during pulmonary coinfection. J Immunol. 2013;191:302–311. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1202824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Feng Y., Kong Y., Barnes P.F., Huang F.-F., Klucar P., Wang X. Exposure to cigarette smoke inhibits the pulmonary T-cell response to influenza virus and Mycobacterium tuberculosis. Infect Immun. 2010;79:229–237. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00709-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nicolai A., Frassanito A., Nenna R., Cangiano G., Petrarca L., Papoff P. Risk factors for virus-induced acute respiratory tract infections in children younger than 3 years and recurrent wheezing at 36 months follow-up after discharge. Pediatr Infect Dis. 2017;36:179–183. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000001385. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corbett E.L., Bandason T., Cheung Y.B., Makamure B., Dauya E., Munyati S.S. Prevalent infectious tuberculosis in Harare, Zimbabwe: burden, risk factors and implications for control. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2009;13:1231–1237. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Cui Z., Zhou Y., Li H., Zhang Y., Zhang S., Tang S. Complex sputum microbial composition in patients with pulmonary tuberculosis. BMC Microbiol. 2012;12:276. doi: 10.1186/1471-2180-12-276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Winglee K., Eloe-Fadrosh E., Gupta S., Guo H., Fraser C., Bishai W. Aerosol Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection causes rapid loss of diversity in gut microbiota. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97048. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097048. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.