In late December, 2019, a cluster of cases of viral pneumonia was linked to a seafood market in Wuhan (Hubei, China), and was later determined to be caused by a novel coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2; previously known as 2019-nCoV).1 The genome sequence of SARS-CoV-2 is similar to, but distinct from, those of two other coronaviruses responsible for large-scale outbreaks in the past: severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV; about 79% sequence identity) and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV; about 50%).2

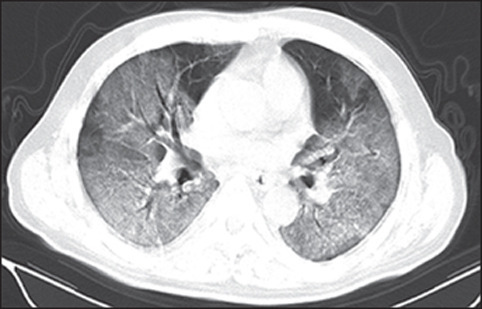

CT has been an important imaging modality in assisting in the diagnosis and management of patients with coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) pneumonia, and reports on the radiological appearances of COVID-19 pneumonia are emerging. In The Lancet Infectious Diseases, Heshui Shi and colleagues3 discuss the CT findings and temporal changes of COVID-19 pneumonia with reference to the time of onset of symptoms, in the largest cohort thus far reported. The predominant CT findings included ground-glass opacification, consolidation, bilateral involvement, and peripheral and diffuse distribution. These findings concur with other reports in smaller cohorts and with our own experience.4, 5, 6 Notably, in Shi and colleagues' study, the asymptomatic (subclinical) group of patients showed early CT changes, supporting what was first observed in a familial cluster with COVID-19 pneumonia.7 Conversely, other studies have shown positive RT-PCR results for SARS-CoV-2 in the absence of CT changes, or abnormal CT findings with initial false-negative RT-PCR results.8 As the epidemic evolves, we are starting to observe the varied presentations of COVID-19 pneumonia, with symptomatic patients showing concordant CT and RT-PCR findings.8 Nevertheless, this small number of individuals with COVID-19 pneumonia poses a diagnostic dilemma given the varied manifestations.

The evolution of the disease on CT is not well understood. Shi and colleagues reported the presence of unilateral ground-glass opacities in a subgroup of 15 asymptomatic patients with COVID-19 pneumonia, substantiating previous anecdotal reports that asymptomatic patients could have CT changes before symptom onset. This finding suggests that CT is a sensitive modality with which to detect COVID-19 pneumonia, even in asymptomatic individuals, and could be considered as a screening tool—together with RT-PCR—when a patient has significant travel history or has had close contact with an infected individual. Furthermore, CT might be a particularly important screening tool in the small proportion of patients who have false-negative RT-PCR results. Shi and colleagues also showed that the lesions that were present in asymptomatic individuals progressed to bilateral diffuse disease with consolidation at around the first to second week after symptom onset.9

In Hubei, there was a surge of diagnoses of COVID-19 on Feb 12 because of the introduction of new diagnostic criteria that included CT changes. These criteria were employed to ensure timely treatment and isolation measures, because of the delays associated with laboratory testing and a large number of patients presenting with respiratory symptoms in the province.

As the predominant pattern seen in COVID-19 pneumonia is ground-glass opacification, detecting COVID-19 with use of chest radiography—on which this type of abnormality is often imperceivable, particularly in patients with few symptoms or low severity—is likely to be challenging. By contrast, chest radiographs were used frequently in the diagnosis of SARS as both ground-glass opacification and consolidation were present early.10, 11

The current literature is partly skewed by the geographical distribution of COVID-19 pneumonia and the preferential use of CT over chest radiograph in China. This preference might be due to the ease of access to CT in China and the lack of requirement for intravenous contrast agent for the examination. Therefore, it is unclear whether the threshold for performing CT evaluation of potential lung changes should be lower when chest radiographs are normal. Further research is needed to better select patients for CT examination, to define the utility of CT in COVID-19 pneumonia, and to explore the application of artificial intelligence in screening chest radiographs in suspected cases.

Overall, we congratulate Shi and colleagues in adding valuable information to the current literature. The authors carefully evaluated the CT findings in a large cohort of patients with COVID-19 pneumonia, providing indirect evidence of the evolution of the CT changes with reference to the onset of symptoms. There is more to be learnt about this novel contagious viral pneumonia; more research is needed into the correlation of CT findings with clinical severity and progression, the predictive value of baseline CT or temporal changes for disease outcome, and the sequelae of acute lung injury induced by COVID-19.

© 2020 Elsevier

Acknowledgments

We declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Huang C, Wang Y, Li X. Clinical features of patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus in Wuhan, China. Lancet. 2020;395:497–506. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30183-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lu R, Zhao X, Li J. Genomic characterisation and epidemiology of 2019 novel coronavirus: implications for virus origins and receptor binding. Lancet. 2020;395:565–574. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30251-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shi H, Han X, Jiang N. Radiological findings from 81 patients with COVID-19 pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30086-4. published online Feb 24. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chung M, Bernheim A, Mei X. CT imaging features of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) Radiology. 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200230. published online Feb 4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Song F, Shi N, Shan F. Emerging coronavirus 2019-nCoV pneumonia. Radiology. 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200274. published online Feb 6. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ng M, Lee E, Yang J. Imaging profile of the COVID-19 infection: radiologic findings and literature review. Radiol Cardiothorac Imaging. 2020;2 doi: 10.1148/ryct.2020200034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Chan JF, Yuan S, Kok KH. A familial cluster of pneumonia associated with the 2019 novel coronavirus indicating person-to-person transmission: a study of a family cluster. Lancet. 2020;395:514–523. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30154-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Xie X, Zhong Z, Zhao W, Zheng C, Wang F, Liu J. Chest CT for typical 2019-nCoV pneumonia: relationship to negative RT-PCR testing. Radiology. 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200343. published online Feb 12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Pan F, Ye T, Sun P. Time course of lung changes on chest CT during recovery from 2019 novel coronavirus (COVID-19) pneumonia. Radiology. 2020 doi: 10.1148/radiol.2020200370. published online Feb 13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Ooi GC, Khong PL, Muller NL. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: temporal lung changes at thin-section CT in 30 patients. Radiology. 2004;230:836–844. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2303030853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ooi CG, Khong PL, Ho JC. Severe acute respiratory syndrome: radiographic evaluation and clinical outcome measures. Radiology. 2003;229:500–506. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2292030737. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]