Abstract

The geographic spread and rapid increase in the cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) caused by a novel coronavirus (MERS-CoV) during the past two months have raised concern about its pandemic potential. Here we call for the rapid development of an effective and safe MERS vaccine to control the spread of MERS-CoV.

Keywords: Coronavirus, MERS-CoV, Receptor, Receptor-binding domain, Vaccine

Very recently, a new case of Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS) coronavirus (MERS-CoV) was reported in a 44-year-old man living in Yemen with no relevant travel history – possibly the first autochthonous case outside of Saudi Arabia. When considered with recent news of the three reported cases of MERS in the United States, there is urgency to consider renewing the global commitment to combat MERS and accelerate the development of a MERS vaccine.

To date, however, the interest and enthusiasm of the global public health community in both MERS and a MERS vaccine could be described as ambivalent. At last year's World Health Assembly in Geneva, Dr. Margaret Chan, the World Health Organization (WHO) Director General, announced that MERS-CoV is “a threat to the entire world”. However, later that summer, a special WHO panel muted such sentiments by indicating that MERS did not yet constitute a “public health emergency of international concern” [1]. As of May 23, 2014, 635 laboratory-confirmed cases of MERS-CoV infection, including 193 deaths, had been reported to WHO from seven countries in the Middle East, two countries in Africa, six countries in Europe, two countries in Asia, and one country in North America [2].

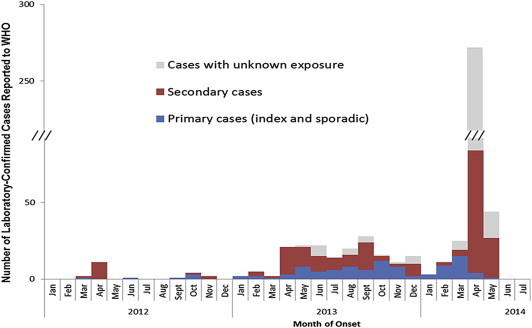

More worrisome, 429 of these cases have been reported since March 27, 2014. A majority of these newly reported cases are secondary cases or cases with unknown exposure (Fig. 1 ), partly reflecting increased surveillance for this disease in Saudi Arabia, but also possibly suggesting an increased ratio of human-to-human transmission of MERS-CoV. Yet a group of WHO experts during a visit to Saudi Arabia failed to recommend any new public health measures beyond ongoing surveillance for respiratory infections. Moreover, no new travel restrictions including restrictions on trade or the annual pilgrimage have been instituted [3]. Of course, this situation could change, pending new developments.

Fig. 1.

Ratios of the primary and secondary cases, and those with unknown exposure among the 536 laboratory-confirmed patients with MERS-CoV infection (as of 8 May 2014). This figure was reproduced from the website of the World Health Organization with their permission. (http://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/archive_updates/en/).

Similar to how the scientific community responded to the outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) CoV that emerged from South China more than a decade ago, several promising avenues for developing a MERS vaccine have been explored. For now, however, many of us have received mixed messages on the urgency of advancing a vaccine development program for MERS-CoV.

In 1973, Harold Bloom, Yale University English professor and literary critic, published his famous book entitled The Anxiety of Influence: A Therory of Poetry. In essence, Bloom advances the hypothesis that poets aspire to write something truly original, but they become hindered in their creative processes by the influence, both conscious and unconscious, of previous works [4].

Anxiety of influence similarly affects virus researchers today because of a medical and scientific disaster that struck NIH and Merck investigators almost 50 years ago during the testing of a first-generation formalin-inactivated respiratory syncytial virus (RSV) vaccine [5]. The vaccine failed to protect infants who received this vaccine in 1966–67, and many became sick from antibody-dependent enhanced respiratory signs and symptoms. Two young children died [6].

Since then, investigators working with experimental respiratory vaccines have proceeded with great caution and even reluctance based on the prospect of causing another such incident. In laboratory animals antibody-dependent immune enhancement is associated with eosinophilic infiltrates in the lungs of laboratory mice following virus challenge. Indeed, experimental whole virus vaccines for SARS have been shown to cause eosinophilic immune enhancement, as well as subunit vaccines comprised of the full spike protein of the SARS coronavirus [7], [8], although to a lesser degree. Such concerns prompted efforts to develop a more restricted receptor binding domain (RBD) of the S protein as a recombinant vaccine [9], [10], which elicits highly effective cross-neutralizing antibody responses in the vaccinated animals [11].

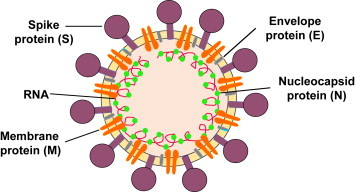

An equivalent RBD molecule has now been identified from MERS-CoV spike protein (Fig. 2 )[12], [13], [14], potentially making it feasible to co-develop this molecule as a recombinant MERS vaccine, alongside an RBD-based SARS vaccine. To date, however, the level of interest from scientific funding agencies to develop MERS vaccines has been modest. When considering the time and expense of developing a safe and effective vaccine against uncertain risk factors, global health policymakers have so far hesitated in prioritizing MERS-CoV vaccines for the purpose of creating a stockpile in the event of a public health emergency.

Fig. 2.

Schematic diagram of MERS-CoV. It contains four structural proteins, including three surface proteins, spike (S), envelope (E), and membrane (M) proteins, and one nucleocapsid (N) protein. The receptor-binding domain (RBD) in the S protein S1 subunit contains major neutralizing epitopes, serving as an attractive target for MERS vaccine [14].

Yet waiting for a full-blown MERS epidemic, or even pandemic, to occur before even beginning vaccine development could result in the loss of many lives, especially in Saudi Arabia. Therefore, the current situation of MERS in the Middle East, especially as we move closer to the Hajj pilgrimage in the fall, will continue to require vigilance by the WHO and other international health agencies, which in turn, must include meaningful and frequent communications with vaccinologists in both academia and industry.

Conflict of interest

The authors have declared that no conflict of interests exist.

Contributor Information

Peter J. Hotez, Email: hotez@bcm.edu.

Shibo Jiang, Email: shibojiang@fudan.edu.cn.

References

- 1.http://news.sciencemag.org/health/2013/07/mers-virus-not-yet-global-emergency-who-panel-says.

- 2.MERS-CoV summary updates. http://www.who.int/csr/don/2014_05_23_mers/en/.

- 3.http://www.emro.who.int/media/news/mers-cov-mission-saudi-arabia.html.

- 4.Bloom Harold. Oxford University Press; USA: 1997. The anxiety of influence: a theory of poetry. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kim H.W., Canchola J.G., Brandt C.D., Pyles G., Chanock R.M., Jensen K. Respiratory syncytial virus disease in infants despite prior administration of antigenic inactivated vaccine. Am J Epidemiol. 1969;89:422–434. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.aje.a120955. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Englund J. In Search of a vaccine for respiratory syncytial virus: the Saga continues. J Infect Dis. 2005;191:1036–1039. doi: 10.1086/427998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jaume M., Yip M.S., Cheung C.Y., Leung H.L., Li P.H., Kien F. Anti-severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus spike antibodies trigger infection of human immune cells via a pH- and cysteine protease-independent FcgammaR pathway. J Virol. 2011;85:10582–10597. doi: 10.1128/JVI.00671-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tseng C.T., Sbrana E., Iwata-Yoshikawa N., Newman P.C., Garron T., Atmar R.L. Immunization with SARS coronavirus vaccines leads to pulmonary immunopathology on challenge with the SARS virus. PLoS ONE. 2012;7:e35421. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0035421. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Du L., He Y., Zhou Y., Liu S., Zheng B.J., Jiang S. The spike protein of SARS-CoV: a target for vaccine and therapeutic development. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2009;7:226–236. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jiang S., Bottazzi M.E., Du L., Lustigman S., Tseng C.T., Curti E. Roadmap to developing a recombinant coronavirus S protein receptor-binding domain vaccine for severe acute respiratory syndrome. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2012;11:1405–1413. doi: 10.1586/erv.12.126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen W.H., Du L., Chag S.M., Ma C., Tricoche N., Tao X. Yeast-expressed recombinant protein of the receptor-binding domain in SARS-CoV spike protein with deglycosylated forms as a SARS vaccine candidate. Hum Vaccin Immunother. 2013 Dec 19;10(3) doi: 10.4161/hv.27464. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Du L., Zhao G., Kou Z., Ma C., Sun S., Poon V.K. Identification of a receptor-binding domain in the S protein of the novel human coronavirus Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus as an essential target for vaccine development. J Virol. 2013;87:9939–9942. doi: 10.1128/JVI.01048-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Du L., Kou Z., Ma C., Tao X., Wang L., Zhao G. A truncated receptor-binding domain of MERS-CoV spike protein potently inhibits MERS-CoV infection and induces strong neutralizing antibody responses: implication for developing therapeutics and vaccines. PLoS ONE. 2013;8:e81587. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0081587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Zhang N., Jiang S., Du L. Current advancements and potential strategies in the development of MERS-CoV vaccines. Expert Rev Vaccines. 2014 Apr 26:761–774. doi: 10.1586/14760584.2014.912134. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]