Ever since the first report of the discovery of an unknown novel coronavirus that had caused pneumonia in Wuhan, China, had filed to WHO by China, on December 31, 2019, the government had instituted drastic measures to contain the outbreak of the epidemic. To keep transparency, the China’s National Health Commission reports confirmed, suspected, recovered and death case numbers daily, yet the epidemiological community is still calling for more information. Specifically, they want to have the critical “Basic Reproduction Number”, . According to Jones [1] and van den Driessche and Watmough [2], , is defined as the expected number of secondary cases produced by a single (typical) infection in a completely susceptible population:

| (1) |

in which is the transmissibility (i.e., probability of infection given contact between a susceptible and infected individual), is the average rate of contact between susceptible and infected individuals, and is the duration of infectiousness. Apparently, is a number depends on many parameters. It is useful in some idealized conditions to predict the development course of a given epidemic in a completely susceptible homogeneous population. However, to determine requires too much information to be realistic in the heat of a developing epidemic. Therefore, it is rarely observed in the field and is usually calculated via a mathematical model relying on tuning, which severely limits its usefulness. Furthermore, to adopt one constant number to describe the full course of an epidemic development is problematic, for the dynamic of the epidemic may exhibit different transmission pattern in difference phase of the event. Additionally, the course of the epidemic could change dynamically subject to various medical and administrative interventions. The frontline personnel in fighting the epidemic would need a quick and robust tool to detect minute and subtle changes of the epidemic course for effective management.

With this point of view, we propose a simple and data driven model based on the physics of natural growth algorithm, for the transmission pattern in an epidemic is quite similar to the natural growth: the more infected, the more infections. In nature, the natural growth occurs everywhere. For example, the diffusivity process in the oceans is controlled by complicated turbulent processes. To investigate this diffusivity process, the non-breaking wave-induced vertical mixing theory [3] was developed and has been successfully applied in the modeling of daily Escherichia coli fluctuations in nearshore water [4]. Such example provides us clue for defining a new parameter of transmission rate.

Considering the above experiences and the limitations, in lieu of the more sophistic , we proposed a simple, data driven and robust way to track the course and to detect the efficacy of any intervention measure for an epidemic dynamically based on the natural growth law:

| (2) |

where is the current existing infected case number at time , which is the total confirmed case number minus the cumulative death and recovered; is the initial number of the existing infected case number at , and is the growth rate at time . To emulate the epidemiological community practice, we further define the transmission rate, , as

| (3) |

It indicates the potential of transmission rate. Specifically, when , the existing infected number would be constant or reach a peak; when , the existing infected number would increase; and when , the existing infected number would decrease.

In this simple model, no nuance on transmission modes or mechanisms is necessary. We have kept the model as simple as possible, but every parameter is a function of time. The values are determined by the observed/reported data directly; therefore, they would offer a tracking tool for the events as the epidemic develops and detecting the efficacy of any intervention measure dynamically. Since the transmission rate is data driven, accurate data is the base for precise estimation of the transmission rate. Furthermore, the larger of the infected number or samples, the lower of the uncertainty for the estimated transmission rate.

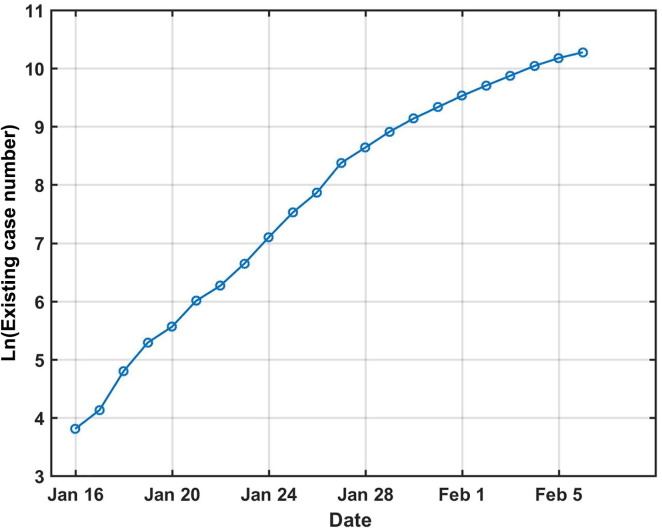

When the daily number data, current existing case number of infected from the China’s National Health Commission are used as input, the case number data are shown in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Daily existing infected case number in China starting on January 16, 2020 plotted on semi-log coordinate.

On the semi-logarithmic coordinate, the overall linear feature of the data indeed suggests an exponential growth pattern as proposed in the natural growth model. On careful examination, one can detect a subtle bending of the curve toward the end. This simple observation is only possible with the help of logarithmic scale. It is much more revealing than the linear scale used in most reports.

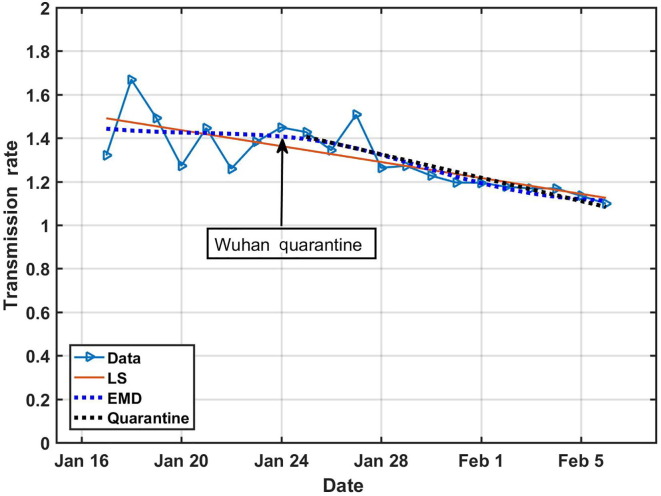

Using these data, we can compute the transmission rate as defined by Eqs. (2), (3). The result is given in Fig. 2 .

Fig. 2.

The transmission rate of 2019-nCoV, with trend lines determined by EMD (dotted blue) and Least Squared (LS, solid red) and the trend after the quarantine of Wuhan (dotted black) added. The quarantine was introduced on January 23, 2020, we count its effects from the following day of January 24. The peak time estimate is made based on the extension of the trend.

Here we have added the trends determined by the traditional Least Square method and Empirical Mode Decomposition (EMD) [5], [6]. The negligible difference especially toward the end supports that the model is robust in terms of the variation of data analysis methods. However, we believe the EMD method is better, for it does not pre-assumed the functional form of the trend. At any rate, we can see a gentle but quantitative downward trend, indicating that the transmission rate is decreasing. The descending rate of the past several days clearly indicates that the implemented measures by Chinese central and local governments are effective. Simple as the result is, it offers more information on the development of the epidemic than the raw number tabulated or plotted in linear scale figures showing daily on public media.

Although the present tool is only for data analysis and event tracking, it also enables us to make an estimate for the future course of the epidemic. If the rate remains at this present course, it is estimated that the existing infected cases would peak 13 days from now (February 6th), and start to decrease from there on based on the trends determined with all the data.

However, if we take only the data after the quarantine was imposed on the City of Wuhan on January 24th (Technically, the quarantine was imposed on January 23rd, but its effects could only be counted on the next day), the trend would be slightly different as shown in the black dotted line in Fig. 2. This trend clearly shows the effectiveness of the quarantine. It is well known that for a disease without effective medicine, quarantine would be the best measure to contain the epidemic. If this trend holds, the epidemic should peak 3 days later from now (February 6th, 2020) on or around February 9th. At that time, the total existing infected cases would be between 37,000 and 44,000. This is a much more optimistic view. Fortunately, it is encouraging to see that the trends of all methods seem to converge.

This estimate is based on the assumption that the overall conditions are not changing. As the quarantine effect becomes more apparent, more hospital mobilized, newly constructed hospitals open, new pharmaceutical interventions introduced, and more efficient medical management method instituted the transmission rate might even decrease faster. However, the large pool of suspected may delay the estimated peak time. Another special condition is also coming up: the return tide of the workers after the Spring Festival holiday, which may increase the transmission rate.

It should be pointed out that an accurate estimate of the peak period and infected number remains a tough task, with large variations for different models. For example, by using the traditional epidemiological model, Wu et al. [7] estimated that the epidemic of Wuhan would peak around April 2020 or even later with reduced transmissibility, and the infected number will be unbelievable high. Yet Prof. Nanshan Zhong, national leading scientist for this epidemic issue, estimated on January 28, 2020 that the peak might appear 7–10 days later. On February 2, Prof. Michael Levitt, Nobel Prize winner from the Stanford University of the United States published a report on website, announced that the peak will appear within one week. Meanwhile, popular media (New York Times, for example) is warning the potential of a pandemic. Facing such confusing information and uncertainty, a simple and robust estimate would serve the public better, we think. Fortunately, it is reassuring that some models based on different mechanisms and assumptions and leading expert in the frontline all produce results converging in a similar range as this simple, direct and data driven one does.

Standard approach might provide more detailed scientific information, if the “Susceptible-Infected-Removed (SIR)” model is tuned correctly. However, that would depend on many assumptions and much more detailed data, which might or might not be available. This present simple, direct, data driven transmission rate proposed here is intuitive, holistic and robust. Under uncertainty of different models, we prefer Ockham’s Razor principle in model selection.

This practical tracking tool for the epidemic course is an urgent societal need and for effective epidemic managing. No much scientific breakthrough is involved. There are of course limitations of this simple data driven model. The most severe one is the lack of epidemiological details. Another limitation is on the characteristics of the population. All models assume homogeneous population. In addition, the large number of suspected cases may influence the final estimation. As the present model is not depending on the details, it is the least influenced by the heterogenous population.

Application of the transmission rate to 2019-nCoV epidemic reveals that the rate has been decreasing, indicating the effective of the quarantine of Wuhan and other strict measures from Chinese government. For example, with a mortality of 0.02%, the recent H1N1 Influenza of 2009–2010 is estimated by WHO [8] to cause a total fatality between 100,000 and 400,000. Yet under quarantine, the much more vicious SARS has caused less than 800 worldwide.

Importantly, under the strict quarantine, if the present trend of transmission rate holds, we estimate the epidemic peak on or around February 9 with the existing infected cases between 37,000 and 44,000. It should be no later than February 19 even for the slow decrease of transmission rate. At least, this simple model could serve as an administrative guide for frontline personnel fighting and managing the epidemic efficiently. And it could also keep the public informed of the general trend of the events better than the raw case numbers.

It should be pointed out that the socio-economic developments and civilization evolution have always been facing grand challenges including climate/environmental changes and extremes [9], and epidemics are one kind of them [10], [11]. The direct and indirect causes of this 2019-nCoV epidemic are still unclear. Consumption of wild animals, sanitation and hygiene practices should be responsible, while environment evolutions including climate change and extreme events may also contribute [12], [13], [14]. But these critical topics are beyond the purview of this note.

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (41821004). We have reported these results to Ministry of Science and Technology, China since February 1, 2020. All data used in this study are public.

Biographies

Norden E. Huang is a member of US National Academy of Engineering, foreign member of the Chinese Academy of Engineering, and former chief scientist of oceanography NASA/GSFC. He received Ph.D. degree in Fluid Mechanics and Mathematics from Johns Hopkins University in 1967. He is a pioneering expert in nonlinear data analysis and the inventor of Hilbert-Huang Transform. He is currently a senior advisor at the First Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources of China.

Fangli Qiao received his Ph.D. degree in Physical Oceanography, and is senior researcher at the First Institute of Oceanography, Ministry of Natural Resources of China. Research activities cover ocean and climate model development, ocean turbulence and air-sea interaction. He is the member of the Executive Planning Group of the UN Decade of Ocean Science for Sustainable Development.

Footnotes

Chinese version of this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.scib.2020.02.005.

Appendix A. Supplementary material

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Jones JH. Notes on Ro. Califonia: Department of Anthropological Sciences; 2007.

- 2.van den Driessche P, Watmough J. Further notes on the basic reproduction number. Mathematical Epidemiology. 2008; 159–178, Part of the Lecture Notes in Mathematics Book Series, Springer.

- 3.Qiao F., Yuan Y., Deng J. Wave turbulence interaction induced vertical mixing and its effects in ocean and climate models. Philosoph Trans Roy Soc London Ser A - Math Phys Eng Sci. 2016;374:20150201. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2015.0201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ge Z., Whitman R., Nevers M. Wave-induced mass transport affects daily Escherichia coli fluctuations in nearshore water. Environ Sci Technol. 2012;46:2204–2211. doi: 10.1021/es203847n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Huang N., Shen Z., Long S. The empirical mode decomposition method and the Hilbert spectrum for non-stationary time series analysis. Proc Roy Soc London A. 1998;4:903–995. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wu Z., Huang N., Long S. On the trend, detrending, and the variability of nonlinear and non-stationary time series. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2007;104:14889–14894. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0701020104. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wu J., Leung K., Leung G. Nowcasting and forecasting the potential domestic and international spread of the 2019-nCoV outbreak originating in Wuhan, China: a modelling study. Lancet. 2020 doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30260-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.World Health Organization. Managing Epidemics: keys facts about major deadly diseases. 2018, pp. 257.

- 9.Liu M., Liu X., Huang Y. Epidemic transition of environmental health risk during China’s urbanization. Sci Bull. 2017;62:92–98. doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2016.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yue R., Lee H. Climate change and plague history in Europe. Sci China Earth Sci. 2018;61:163–177. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen F., Fu B., Xia J. Major advances in studies of the physical geography and living environment of China during the past 70 years and future prospects. Sci China Earth Sci. 2019;62:1665–1701. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dong G. Understanding past human-environment interaction from an interdisciplinary perspective. Sci Bull. 2018;63:1023–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.scib.2018.07.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hong X., Tian H., Lin X. Influence of extreme weather and meteorological anomalies on outbreaks of influenza A (H1N1) Chin Sci Bull. 2013;58:741–749. doi: 10.1007/s11434-012-5571-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liu Q., Tan Z., Sun J. Changing rapid weather variability increases influenza epidemic risk in a warming climate. Environ Res Lett. 2020 doi: 10.1088/1748-9326/ab70bc. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.