Abstract

Objective

We aimed to assess the effects of amoxicillin treatment in adult patients presenting to primary care with a lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) who were infected with a potential bacterial, viral, or mixed bacterial/viral infection.

Methods

This multicentre randomized controlled trial focused on adults with LRTI not suspected for pneumonia. Patients were randomized to receive either antibiotic (amoxicillin 1 g) or placebo three times daily for 7 consecutive days using computer-generated random numbers (follow-up 28 days). In this secondary analysis of the trial, symptom duration (primary outcome), symptom severity (scored 0–6), and illness deterioration (reconsultation with new or worsening symptoms, or hospital admission) were analysed in pre-specified subgroups using regression models. Subgroups of interest were patients with a (strictly) bacterial, (strictly) viral, or combined infection, and patients with elevated values of procalcitonin, C-reactive protein, or blood urea nitrogen.

Results

2058 patients (amoxicillin n = 1036; placebo n = 1022) were randomized. Treatment did not affect symptom duration (n = 1793). Patients from whom a bacterial pathogen only was isolated (n = 207) benefited from amoxicillin in that symptom severity (n = 804) was reduced by 0.26 points (95% CI −0.48 to −0.03). The odds of illness deterioration (n = 2024) was 0.24 (95% CI 0.11 to 0.53) times lower from treatment with amoxicillin when both a bacterial and a viral pathogen were isolated (combined infection; n = 198).

Conclusions

Amoxicillin may reduce the risk of illness deterioration in patients with a combined bacterial and viral infection. We found no clinically meaningful benefit from amoxicillin treatment in other subgroups.

Keywords: Aetiology, Amoxicillin, Illness deterioration, Lower respiratory tract infection, Symptom duration, Symptom severity

Introduction

Acute lower respiratory tract infection (LRTI) is common in primary care [1]. Antibiotic treatment is of limited benefit both overall and in subgroups at higher risk of an adverse course. Nevertheless, antibiotics are prescribed for most patients with LRTI [2], [3], [4], [5]. Primary analysis of the largest trial to date, the Genomics to combat Resistance against Antibiotics in Community-acquired LRTI (GRACE; http://www.grace-lrti.org) randomized placebo controlled trial (RCT), found no clear evidence of a clinically meaningful benefit from treatment with amoxicillin [2]. A follow-up analysis that examined the benefit of amoxicillin in clinically defined subgroups of patients with LRTI who are most likely to be prescribed antibiotics (i.e. patients with green sputum or those with significant comorbidities) found no clear evidence of meaningful benefit from amoxicillin even in these subgroups [3]. Only those patients with evidence of pneumonia on chest X-ray benefited from amoxicillin treatment [6].

However, it is unclear whether patients infected with bacterial pathogens might selectively benefit from antibiotic treatment, and filling this evidence gap could help better target antibiotic prescribing in primary care. This secondary analysis of the GRACE RCT therefore aims to assess whether patients from whom potential bacterial pathogens are isolated receive benefit from amoxicillin treatment. In addition, we aimed to assess whether isolation of a viral pathogen and high levels of C-reactive protein (CRP), blood urea nitrogen (BUN), or procalcitonin (PCT) were associated with benefit from treatment with amoxicillin [7], [8], [9].

Methods

Data

The details of the GRACE RCT have been described in detail elsewhere [2]. In summary, non-pregnant adults presenting to primary care with acute cough, in whom pneumonia was not suspected, were recruited between November 2007 and April 2010 by primary care physicians in 16 networks across 12 European countries (Belgium, England, France, Germany, Italy, The Netherlands, Poland, Spain, Slovakia, Slovenia, Sweden, and Wales). Patients who did not consume antibiotics in the month before consultation were randomized to receive either an antibiotic (amoxicillin 1 g) or a placebo three times daily for 7 consecutive days. All patients were asked to complete a symptom diary daily until their symptoms had settled (up to a maximum of 28 days). The diary recorded the severity of cough, phlegm, shortness of breath, wheezing, runny nose, chest pain, muscle ache, headache, disturbed sleep, feeling unwell, fever, and interference with daily activities. Symptoms were scored on a 7-point scale (0: normal/not affected, 1: very little problem, 2: slight problem, 3: moderately bad, 4: bad, 5: very bad, 6: as bad as it could be) [10]. For each patient, a nasopharyngeal swab was taken on the day of presentation. This sample was then analysed using bacterial and viral polymerase chain reaction analysis. We tested for both bacterial pathogens (Streptococcus pneumoniae, Haemophilus influenza, Mycoplasma pneumoniae, Chlamydia pneumoniae, Bordetella pertussis, Legionella pneumoniae) and viral pathogens (rhinovirus, influenza virus, coronavirus, respiratory syncytial virus, human metapneumovirus, parainfluenza virus, adenovirus, polyomavirus, bocavirus) [11]. Samples with a pathogen present, either bacterial or viral, were referred to as confirmed infections. Samples in which a bacterial pathogen was detected were referred to as bacterial infections. If no viral pathogens were present in these samples, they were referred to as purely bacterial infections. Samples in which a viral pathogen was detected were referred to as viral infections. If no bacterial pathogens were present in these samples, they were referred to as purely viral infections. Samples in which both a bacterial and a viral pathogen were detected were referred to as combined infections. Note that these categorizations are not mutually exclusive. Within 24 hours of presentation to the GP, a venous blood sample was obtained. CRP and BUN were measured using the conventional immunoturbidimetric method. PCT was measured using a rapid sensitive assay [11]. We defined an elevated CRP, PCT, and BUN as the top 25% of measurements in our patient population (referred to as high CRP, high PCT, and high BUN, respectively).

Main outcomes

Symptom duration: The primary outcome was the duration of symptoms rated moderately bad or worse by the patient (score 3 or above) following the initial presentation (in days) [12].

Symptom severity: A secondary outcome was symptom severity, calculated as the mean diary score for all symptoms on days 2–4 (rated by the patient). This time frame was selected because before day 2 antibiotics will have had little chance to provide benefit, and after day 4 the overall symptom severity is less than moderately bad [12].

Illness deterioration: An additional secondary outcome was illness deterioration, defined as a return to the physician with worsening symptoms, new symptoms, new signs or illness requiring admission to hospital within 4 weeks of the initial consultation (documented through a notes review) [13].

Analysis

We fitted a Cox regression model for symptom duration (allowing for censoring), a linear regression model for symptom severity, and a logistic regression model for illness deterioration [14], [15], [16]. All analyses controlled for severity of symptoms at baseline and included an interaction term between a particular subgroup (in the studied subgroup or not) and treatment (amoxicillin or placebo). This interaction term was used to assess whether the effectiveness of amoxicillin treatment varied by the subgroup. Similar models, excluding the interaction term, were fitted for patients in the selected subgroup.

The subgroups of interest were patients with a confirmed, bacterial, purely bacterial, viral, purely viral, or combined infection. We were also interested in subgroups with a high CRP, high BUN, or high PCT. Subgroups were not mutually exclusive.

Ethics approval

The study was approved by ethics committees in all participating countries. The competent authority in each country also gave their approval. Patients who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were given written and verbal information on the study and provided written informed consent. The GRACE RCT is registered with EudraCT (2007-001586-15), UKCRN Portfolio (ID 4175), ISRCTN (52261229), and FWO (G.0274.08N).

Results

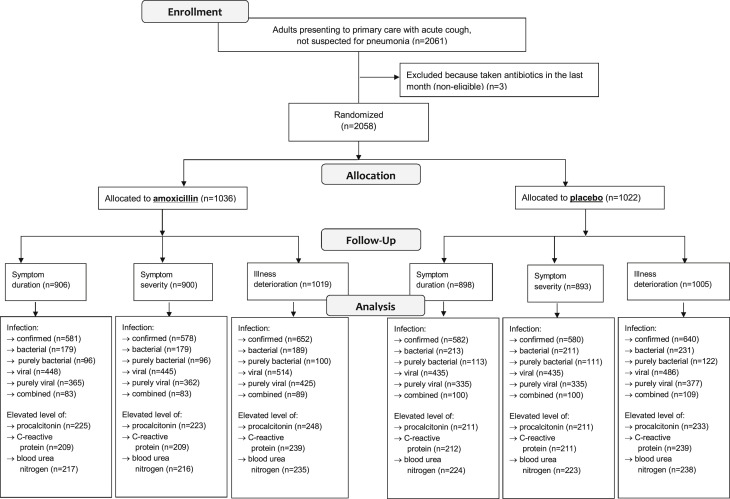

In total, 2058 patients (out of 2061) that did not consume antibiotics in the month before consultation were randomized. Symptom duration and symptom severity were reported for 87% (1793/2058) and 88% (1804/2024) of patients, respectively. Illness deterioration (or no deterioration) was documented in 98% (2024/2058) of whom 18% (355/2024) experienced illness deterioration. The vast majority of those with illness deterioration represented reconsultation with new or worsening symptoms. Sample size information for subgroup analyses is presented in Fig. 1 .

Fig. 1.

Patient flow chart.

Symptom duration

No subgroups were identified that were significantly more likely to benefit from amoxicillin for the duration of symptoms (in days) rated moderately bad or worse (Table 1 ).

Table 1.

Symptom durationa in patients consulting in primary care with LRTI treated with amoxicillin versus placebo

| Median symptom duration (IQR) |

Interaction termb (95% CI) | p-Value | Hazard ratio for subgroupb (95% CI) | p-Value | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Amoxicillin | Placebo | |||||

| Whole cohort (n = 1804) | 6 (3–11) | 7 (3–13) | 1.06 (0.96 to 1.17) | 0.268 | ||

| Confirmed infection (n = 1163) | 6 (3–11) | 7 (4–11) | 0.92 (0.75 to 1.14) | 0.435 | 1.03 (0.91 to 1.16) | 0.673 |

| Bacterial infection (n = 392) | 6 (3–16) | 7 (4–14) | 0.96 (0.76 to 1.23) | 0.767 | 1.03 (0.83 to 1.27) | 0.821 |

| Purely bacterial infection (n = 209) | 5 (3–16.5) | 9 (5–17) | 1.10 (0.80 to 1.51) | 0.554 | 1.13 (0.84 to 1.53) | 0.421 |

| Viral infection (n = 883) | 6 (3.5–11) | 7 (3–11) | 0.92 (0.75 to 1.12) | 0.394 | 1.01 (0.88 to 1.17) | 0.884 |

| Purely viral infection(n = 700) | 6 (3–11) | 7 (3–11) | 0.98 (0.80 to 1.21) | 0.855 | 1.04 (0.89 to 1.23) | 0.599 |

| Combined infection (n = 183) | 7 (4–14) | 6 (3.5–11) | 0.83 (0.59 to 1.15) | 0.250 | 0.89 (0.65 to 1.21) | 0.450 |

| High PCT (n = 436) | 6 (4–13) | 7 (4–13) | 1.06 (0.84 to 1.34) | 0.602 | 1.09 (0.89 to 1.33) | 0.423 |

| High BUN (n = 441) | 6 (3–13) | 7 (3–13) | 0.96 (0.76 to 1.21) | 0.723 | 0.99 (0.81 to 1.22) | 0.956 |

| High CRP (n = 421) | 6 (4–11) | 7 (4–12) | 1.03 (0.81 to 1.31) | 0.797 | 1.06 (0.86 to 1.31) | 0.567 |

BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CRP, C-reactive protein; IQR, interquartile range; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; PCT, procalcitonin.

Calculated as the median (IQR) number of days with symptoms rated moderately bad or worse by the patient following the initial presentation.

Estimates controlled for baseline symptom severity; values <1 favour amoxicillin.

Symptom severity

Patients with a purely bacterial infection benefitted from amoxicillin treatment (Table 2 ; interaction term −0.25 (95% CI −0.49 to 0.00); the mean symptom severity score was 0.26 (95% CI −0.48 to −0.03) points lower compared with patients on placebo (Table 2).

Table 2.

Symptom severitya (standard deviation) in patients consulting in primary care with LRTI treated with amoxicillin versus placebo

| Amoxicillin | Placebo | Interaction termb (95% CI) | p-Value | Difference for subgroupb (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole cohort (n = 1793) | 1.59 (0.95) | 1.70 (1.01) | −0.07 (−0.15 to 0.01) | 0.065 | ||

| Confirmed infection (n = 1158) | 1.71 (0.99) | 1.82 (1.02) | 0.03 (−0.13 to 0.19) | 0.720 | −0.06 (−0.16 to 0.04) | 0.221 |

| Bacterial infection (n = 390) | 1.56 (0.95) | 1.87 (1.05) | −0.09 (−0.28 to 0.10) | 0.330 | −0.14 (−0.31 to 0.03) | 0.108 |

| Purely bacterial infection (n = 207) | 1.44 (0.95) | 1.90 (1.09) | −0.25 (−0.49 to 0.00) | 0.048 | −0.26 (−0.48 to −0.03) | 0.027 |

| Viral infection (n = 880) | 1.78 (1.00) | 1.83 (1.01) | 0.12 (−0.03 to 0.28) | 0.119 | −0.02 (−0.13 to 0.10) | 0.801 |

| Purely viral infection (n = 697) | 1.80 (1.01) | 1.83 (1.01) | 0.09 (−0.07 to 0.25) | 0.251 | −0.02 (−0.15 to 0.11) | 0.755 |

| Combined infection (n = 183) | 1.69 (0.94) | 1.84 (1.00) | 0.10 (−0.15 to 0.36) | 0.423 | −0.01 (−0.27 to 0.25) | 0.943 |

| High PCT (n = 434) | 1.67 (0.98) | 1.87 (1.14) | −0.09 (−0.27 to 0.09) | 0.326 | −0.13 (−0.30 to 0.04) | 0.144 |

| High BUN (n = 439) | 1.45 (0.93) | 1.52 (0.98) | −0.03 (−0.21 to 0.16) | 0.782 | −0.08 (−0.23 to 0.07) | 0.294 |

| High CRP (n = 420) | 1.88 (1.00) | 2.03 (1.03) | −0.07 (−0.25 to 0.12) | 0.473 | −0.12 (−0.29 to 0.06) | 0.201 |

BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CRP, C-reactive protein; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; PCT, procalcitonin.

Calculated as the mean (standard deviation) diary score for all symptoms on days 2–4 (rated by the patient).

Estimates controlled for baseline symptom severity; negative values favour amoxicillin.

Illness deterioration

Patients with a bacterial infection benefited from amoxicillin in terms of illness deterioration (Table 3 ; interaction term 0.47 (95% CI 0.27 to 0.82), OR 0.46 (95% CI 0.29 to 0.75)).

Table 3.

Illness deteriorationa in patients consulting in primary care with LRTI treated with amoxicillin versus placebo

| Amoxicillin | Placebo | Interaction termb (95% CI) | p-Value | Odds ratio for subgroupb (95% CI) | p-Value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Whole cohort (n = 2024) | 162/1019 | 193/1005 | 0.80 (0.63 to 1.00) | 0.051 | ||

| Confirmed infection (n = 1292) | 100/652 | 137/640 | 0.58 (0.36 to 0.95) | 0.029 | 0.67 (0.50 to 0.88) | 0.005 |

| Bacterial infection (n = 420) | 30/189 | 67/231 | 0.47 (0.27 to 0.82) | 0.007 | 0.46 (0.29 to 0.75) | 0.002 |

| Purely bacterial infection (n = 222) | 21/100 | 32/122 | 0.91 (0.46 to 1.79) | 0.792 | 0.75 (0.40 to 1.40) | 0.364 |

| Viral infection (n = 1000) | 72/514 | 98/486 | 0.66 (0.41 to 1.04) | 0.075 | 0.64 (0.46 to 0.90) | 0.010 |

| Purely viral infection (n = 802) | 63/425 | 63/377 | 1.12 (0.69 to 1.81) | 0.639 | 0.87 (0.59 to 1.27) | 0.464 |

| Combined infection (n = 198) | 9/89 | 35/109 | 0.26 (0.11 to 0.59) | 0.001 | 0.24 (0.11 to 0.53) | <0.001 |

| High PCT (n = 481) | 39/248 | 59/233 | 0.62 (0.36 to 1.06) | 0.079 | 0.55 (0.35 to 0.86) | 0.010 |

| High BUN (n = 473) | 40/235 | 45/238 | 1.15 (0.67 to 1.99) | 0.605 | 0.88 (0.55 to 1.41) | 0.593 |

| High CRP (n = 478) | 41/239 | 49/239 | 1.03 (0.60 to 1.75) | 0.927 | 0.80 (0.51 to 1.27) | 0.350 |

BUN, blood urea nitrogen; CRP, C-reactive protein; LRTI, lower respiratory tract infection; PCT, procalcitonin.

Defined as a return to the physician with worsening symptoms, new symptoms, new signs, or illness requiring admission to hospital within 4 weeks of the initial consultation (determined through a notes review).

Estimates controlled for baseline symptom severity; values <1 favour amoxicillin.

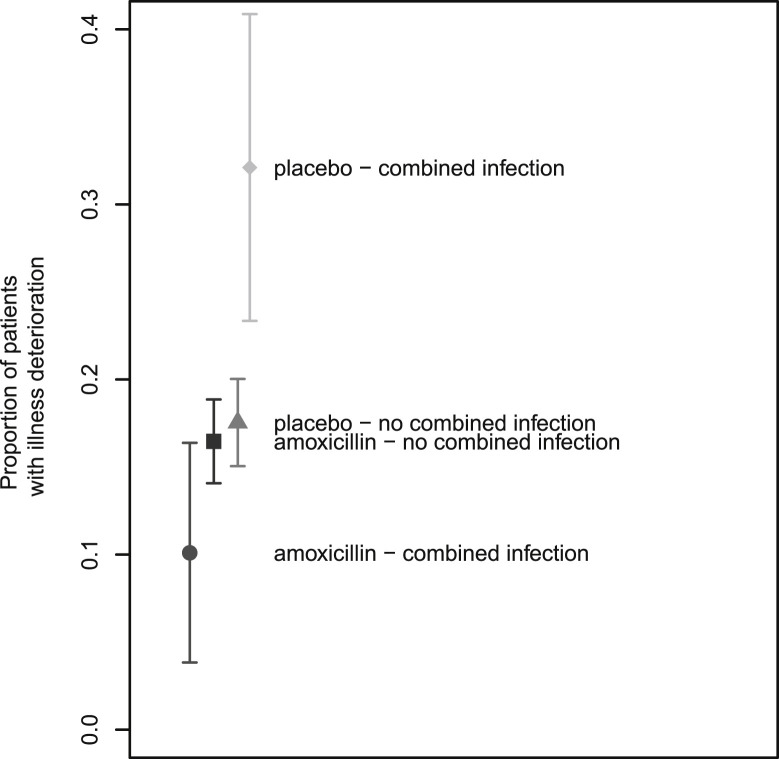

Patients with a combined infection treated with amoxicillin were less likely to experience illness deterioration (Table 3; interaction term 0.26 (95% CI 0.11; 0.59), OR 0.24 (95% CI 0.11 to 0.53)), with 32% (95% CI 23 to 41%) of patients receiving placebo experienced illness deterioration compared with only 10% (95% CI 4 to 16%) of patients receiving amoxicillin (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 2.

Interaction between amoxicillin treatment (versus placebo) and having a combined infection (versus not having one): estimates and 95% CI.

Discussion

We found no clear evidence of clinically meaningful benefit in terms of symptom duration from amoxicillin treatment in patents consulting in primary care with LRTI and from whom we isolated potential bacterial pathogens, viral pathogens, or identified mixed viral/bacterial infections. However, amoxicillin treatment did reduce symptom severity among patients with a purely bacterial infection, and did reduce the risk of illness deterioration in patients with a combined infection, but this effect was not seen among those with a purely bacterial infection.

Previous analyses from this GRACE trial of amoxicillin versus placebo in patients presenting with acute LRTI in primary care found that amoxicillin provided little benefit, both overall and in patients aged 60 and above. In fact, amoxicillin treatment was even associated with slight harm, in that more patients experienced side effects than were prevented from experiencing illness deterioration [2]. A secondary subgroup analysis found that only those patients with significant comorbidities (mostly asthma or chronic obstructive pulmonary disease) benefitted from amoxicillin treatment in terms of reduced symptom severity between days 2 and 4 after first consulting in primary care. However, there was no benefit in terms of symptom duration or odds of illness deterioration, suggesting questionable clinical significance of the modest statistical short-term benefits of amoxicillin treatment in this subgroup [3].

The secondary subgroup analysis presented here has found that patients with a purely bacterial infection benefit from amoxicillin in terms of reduced symptom severity, and that patients with a combined infection benefit from amoxicillin in terms of a reduced chance of illness deterioration. Although the benefit from amoxicillin treatment in those infected only by potential bacterial pathogens is of questionable clinical significance and has only borderline statistical significance, the effect in the combined infection group was an almost 20% reduction in the probability of illness deterioration.

We only found clear evidence of benefit (with p-values below 0.01) from amoxicillin treatment in the group of patients who had a bacterial infection. Given that the amoxicillin treatment is on average ineffective in patients with a purely bacterial infection, the effect of antibiotics in patients with a bacterial infection is driven by the effect in those patients with a combined infection. Assuming that this effect was not a result of chance, it may be biologically plausible: viral infections may predispose to secondary bacterial infections by causing mucosal damage or inflammation, lead to a longer or more severe illness course, and thus make these patients more likely to benefit from amoxicillin [17], [18], [19]. However, the number of patients with a combined infection (9.6%; 199/2056) who could potentially benefit from antibiotic treatment indicates that the clinical impact of developing prediction rules or point of care tests for such patients is limited: 50 patients would have to be tested with a range of bacterial and viral diagnostic tests to identify five who have a combined infection, and all of these would have to be treated for one individual to benefit. Not only would such a policy need to be shown to be cost-effective in the short term, but the potential medicalization of illnesses (by signalling to the population that people with LRTI need to be tested) would have to be considered. Neither symptom duration nor symptom severity were clearly affected by amoxicillin treatment, and the odds of illness deterioration was influenced by amoxicillin treatment only in a very specific subgroup. The potential benefits of amoxicillin treatment should therefore be balanced against side effects, such as diarrhoea, nausea, or skin rash and the long-term risk of antibiotic resistance [20]. Thus, most of these patients should probably not be prescribed an antibiotic, and/or clinicians could consider using a delayed antibiotic prescription to avoid inappropriate use of antibiotics [21]. Nevertheless, it is important to be aware of the potential harm caused by under-treatment of a combined infection, so all patients must be given clear advice about when to reconsult.

Strengths and limitations

The findings from this study are applicable to European primary care clinical practice, as patient recruitment took place in 16 networks across 12 European countries. Some of the subgroups we studied were small, increasing risk of a Type II error. The subgroup with combined bacterial and viral infection was also not specified in advance, which increases the risk of a ‘false positive’ result (type I error) from multiple comparisons, and thus the results should be interpreted with caution. Similarly, the impact of amoxicillin on symptom severity among patients with a purely bacterial infection was of borderline significance, and was also of doubtful clinical importance. In contrast, the impact of amoxicillin treatment on reducing the risk of illness deterioration in patients with a bacterial infection, and in patients with a combined infection, was highly statistically significant.

Conclusion

We found no clear evidence of benefit from amoxicillin treatment in adults presenting to primary care with LRTI for symptom severity or duration, irrespective of aetiology or biomarker test results. Amoxicillin treatment does reduce the risk of illness deterioration when both a viral and a bacterial pathogen are isolated. However, point of care testing to target antibiotic prescribing only to those with a combined bacterial and viral infection is unlikely to be a cost-effective.

Acknowledgements

We thank all the clinicians and patients who consented to be part of GRACE, without whom this study would not have been possible. We are grateful to key members of the GRACE project group whose hard work has made this study possible, including Niels Adriaenssens, Jordi Almirall, Curt Brugman, Slawomir Chlabicz, An De Sutter, Mel Davies, Maciek Godycki-Cwirko, Patricia Fernandez, Iris Hering, Kerenza Hood, Greet Ieven Tom Schaberg, Antoni Torres, Anna Kowalczyk, Christine Lammens, Marieke Lemiengre, Frank Leus, Katherine Loens, Artur Mierzecki, Michael Moore, Magdalena Muras, Gilly O'Reilly, Nuria Sanchez Romano, Matteu Serra Prat, Jackie Swain, Robert Veen, and Tricia Worby.

Editor: Paul, Mical

Contributor Information

the GRACE project group:

J. Almirall, C. Brugman, S. Chlabicz, A. De Sutter, M. Davies, M. Godycki-Cwirko, P. Fernandez, I. Hering, K. Hood, G.I.T. Schaberg, A. Torres, A. Kowalczyk, C. Lammens, M. Lemiengre, F. Leus, K. Loens, A. Mierzecki, M. Moore, M. Muras, G. O'Reilly, N.S. Romano, M.S. Prat, J. Swain, R. Veen, and T. Worby

Transparency declaration

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare. GRACE was funded by the European Community's Sixth Framework Programme (grant agreement 518226). Work in the UK was also supported by the National Institute for Health Research, in Barcelona by 2009 SGR 911 Ciber de Enfermedades Respiratorias (Ciberes CB06/06/0028), and in Belgium by the Research Foundation—Flanders (FWO; G.0274.08N). Financial support from the Methusalem financing program of the Flemish Government is also gratefully acknowledged. NH acknowledges support from the University of Antwerp scientific chair in evidence-based vaccinology, financed in 2009–2017 by a gift from Pfizer and GSK. This publication has been financially supported through the European Science Foundation, in the framework of the Research Networking Program TRACE (www.esf.org/trace). The funders had no role in study design, data collection and analysis, decision to publish, or preparation of the manuscript.

References

- 1.Gibson G.J., Loddenkemper R., Lundbäck B., Sibille Y. Respiratory health and disease in Europe: the new European lung white Book. Eur Respir J. 2013;42:559–563. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00105513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Little P., Stuart B., Moore M., Coenen S., Butler C.C., Godycki-Cwirko M. Amoxicillin for acute lower-respiratory-tract infection in primary care when pneumonia is not suspected: a 12-country, randomised, placebo-controlled trial. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:123–129. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(12)70300-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Moore M., Stuart B., Coenen S., Butler C.C., Goossens H., Verheij T.J.M. Amoxicillin for acute lower respiratory tract infection in primary care: subgroup analysis of potential high-risk groups. Br J Gen Pract. 2014;64:e75–e80. doi: 10.3399/bjgp14X677121. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Butler C.C., Hood K., Verheij T., Little P., Melbye H., Nuttall J. Variation in antibiotic prescribing and its impact on recovery in patients with acute cough in primary care: prospective study in 13 countries. BMJ. 2009;338:b2242. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2242. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butler C.C., Hood K., Kelly M.J., Goossens H., Verheij T., Little P. Treatment of acute cough/lower respiratory tract infection by antibiotic class and associated outcomes: a 13 European country observational study in primary care. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2010;65:2472–2478. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkq336. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Teepe J., Little P., Elshof N., Broekhuizen B.D.L., Moore M., Stuart B. Amoxicillin for clinically unsuspected pneumonia in primary care: subgroup analysis. Eur Respir J. 2015:47. doi: 10.1183/13993003.00611-2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Simon L., Gauvin F., Amre D.K., Saint-Louis P., Lacroix J. Serum procalcitonin and C-reactive protein levels as markers of bacterial infection: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Infect Dis. 2004;39:206–217. doi: 10.1086/421997. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chalmers J.D., Singanayagam A., Akram A.R., Mandal P., Short P.M., Choudhury G. Severity assessment tools for predicting mortality in hospitalised patients with community-acquired pneumonia. Systematic review and meta-analysis. Thorax. 2010;65:878–883. doi: 10.1136/thx.2009.133280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Akram A.R., Chalmers J.D., Hill A.T. Predicting mortality with severity assessment tools in out-patients with community-acquired pneumonia. QJM. 2011;104:871–879. doi: 10.1093/qjmed/hcr088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Watson L., Little P., Moore M., Warner G., Williamson I. Validation study of a diary for use in acute lower respiratory tract infection. Fam Pract. 2001;18:553–554. doi: 10.1093/fampra/18.5.553. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Teepe J., Broekhuizen B.D.L., Loens K., Lammens C., Ieven M., Goossens H. Predicting the presence of bacterial pathogens in the airways of primary care patients with acute cough. CMAJ. 2016;189:E50. doi: 10.1503/cmaj.151364. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Little P., Rumsby K., Kelly J., Watson L., Moore M., Warner G. Information leaflet and antibiotic prescribing strategies for acute lower respiratory tract infection. JAMA. 2005;293:3029. doi: 10.1001/jama.293.24.3029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hay A.D., Fahey T., Peters T.J., Wilson A. Predicting complications from acute cough in pre-school children in primary care: a prospective cohort study. Br J Gen Pract. 2004;54:9–14. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cox D.R. Two further applications of a model for binary regression. Biometrika. 1958;45:562–565. doi: 10.1093/biomet/45.3-4.562. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Quandt R.E. The estimation of the parameters of a linear regression system obeying two separate regimes. J Am Stat Assoc. 1958;53:873. doi: 10.2307/2281957. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Efron B. The efficiency of logistic regression compared to normal discriminant analysis. J Am Stat Assoc. 1975;70:892. doi: 10.2307/2285453. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McCullers J.A. The co-pathogenesis of influenza viruses with bacteria in the lung. Nat Rev Microbiol. 2014;12:252–262. doi: 10.1038/nrmicro3231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Marom T., Alvarez-Fernandez P.E., Jennings K., Patel J.A., McCormick D.P., Chonmaitree T. Acute bacterial sinusitis complicating viral upper respiratory tract infection in young children. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2014;33:803–808. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hament J.-M., Kimpen J.L., Fleer A., Wolfs T.F. Respiratory viral infection predisposing for bacterial disease: a concise review. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1999;26:189–195. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1999.tb01389.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Malhotra-Kumar S., Van Heirstraeten L., Coenen S., Lammens C., Adriaenssens N., Kowalczyk A. Impact of amoxicillin therapy on resistance selection in patients with community-acquired lower respiratory tract infections: a randomized, placebo-controlled study. J Antimicrob Chemother. 2016;71:3258–3267. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkw234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Little P., Stuart B., Smith S., Thompson M.J., Knox K., van den Bruel A. Antibiotic prescription strategies and adverse outcome for uncomplicated lower respiratory tract infections: prospective cough complication cohort (3C) study. BMJ. 2017:357. doi: 10.1136/bmj.j2148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]