Seasonality of disease, mainly of respiratory pathogens, is a key feature [1]. The Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) is a newly emerging respiratory viral infection and causes asymptomatic or mild infection and may result in a life threatening disease with a high case fatality rate. As reported by the World Health Organization, the virus caused a total of 2143 laboratory-confirmed cases from 27 countries, including 750 (35%) deaths. It is important to understand the transmission of the virus and the occurence of any seasonal variation in the transmission between humans and animals. Based on the occurence of initial clusters in April 2012, April–May 2013, and May 2014, it was concluded that there was a significant MERS-CoV activity in March–May of each year. Initial hospital outbreaks also occurred in April 2012 (Zarqa public health hospital, Jordan), April–May 2013 (Al-Hasa Outbreak) and April–May 2014 (Jeddah outbreak). Thus, it was thought that MERS-CoV occurs predominantly during the spring (March–May). The occurrence of cases in the spring raises the possibility of seasonal cycles of MERS-CoV as camels give birth in March (spring) and MERS-CoV occurs commonly in young camels. Seasonal variation may reflect the risk of transmission of MERS-CoV between animals and humans. Here, we analyze publicly available MERS-CoV data to evaluate any seasonal variation of MERS-CoV. We retrospectively analyzed reported cases between January 2013 and December 2017. We reviewed all reported MERS-CoV cases from the Saudi Ministry of Health website and the World Health Organization [2,3]. Primary cases were considered when the cases were not linked to other cases in the community or in healthcare settings.

The analysis included seasonal variation and monthly variation over the included years. Statistical analysis was done using Minitab® (Minitab Inc. Version 17. PA 16801, USA; 2017). A time-trend analysis was used to generate a linear trend for the monthly distribution and then for seasonal distribution of the cases. We generated a forecasting of primary MERS-CoV cases over time and exteneded this for an additional six seasons. We then used the moving average plot of primary MERS-CoV cases with forecast in relation to the seasons for an additional four seasons. A significant P value was considered for p < 0.05. We also used the classic multiplicative time series in order to decompose the original data into seasonal, irregular and trend component and obtained the effects.

A total of 2025 cases were reported to the World Health Organization. All cases were confirmed MERS-CoV. However, it was only possible to classify cases as primary or secondary cases from January 2015 onwards. Thus, further analysis of seasonality was done on cases reported in 2015–2017.

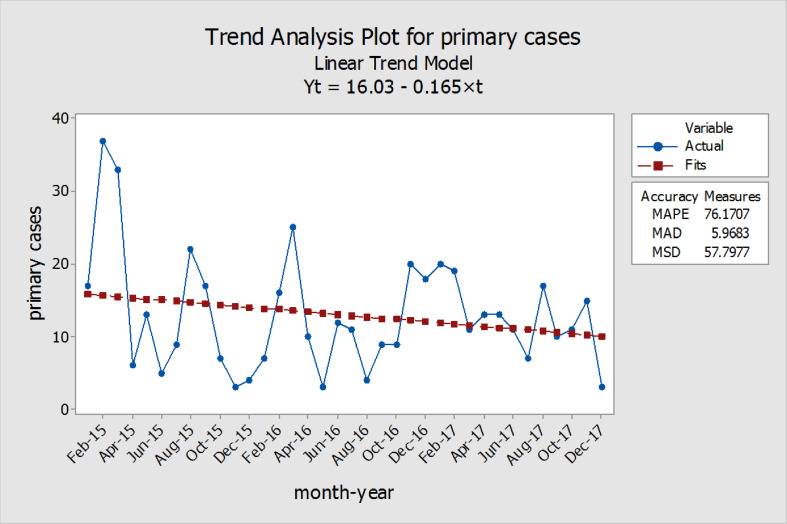

There was an overall negative trend and reduction in the monthly number of primary MERS-CoV cases between 2015 and 2017 (Fig. 1 ) with a regression analysis showing P value of 0.023. The curve of case numbers clearly shows some peaks and significant variations overtime. These peaks do not appear to follow a seasonal pattern (no clear relation with months). However, these variations may be due to climatic factors, like temperature or hygrometry. Seasonal analysis of the data showed an initial increase in number of cases in the winter and the summer of 2015, a lower number of cases in 2016 and a higher number of cases in the winter of 2017. Although, taking all the cases together the majority of cases occurred in the winter (33%), the summer (27.4%) and the fall (21.4%). Using trend analysis and forecasting into the future, the analysis showed that primary MERS-CoV cases would be about 5 cases in the spring of 2019.

Fig. 1.

Monthly distribution and time trends of Primary MERS-CoV cases with the Index (X-axis) representing January 2015 to December 2017.

Decomposition of the MERS-CoV cases using the centered moving average showed that August 2015 rate was 83% above the average, and that summer 2015 and winter 2017 were 40% and 31% above the moving average.

Since the emergence of MERS-CoV infection in 2012, there was an increase in the annual number of MERS-CoV cases in 2014 and 2015 with subsequent reduction in the cases in the following two years.

Seasonal variations among the transmission of respiratory viruses reflect the risk of animal-human transmission, difference in the circulating viruses, and the natural reservoirs of specific viruses [4]. Since the emergence of MERS-CoV, it was though that MERS-CoV transmission occurs through two seasons: the spring (March–May) and the fall (September-November) [5]. Seasonal variation may occur due to dromedaries’ calving season (November and March). In one study, the prevalence of MERS-CoV was higher among camels in the winter time (71.5%) than the summer time (6.2%) [6].

In an analysis of MERS-CoV cases from June 2012 to July 2016, authors estimated mean monthly data for all the included studies and showed that MERS-CoV may have two peaks in the winter and summer months [7]. However, we showed no definite seasonal variation of primary MERS-CoV cases despite initial peak in February and August 2015 and in March 2017. Our analysis is different as we relied on primary MERS-CoV cases. It is important to keep in mind that 37.5% of reported cases are related to health care-associated infections, 16% were secondary to contact with an infected family member and 8.2% had no identified risk factors. Thus, focusing on primary cases only to understand transmission pathways might be insufficient. Since mechanisms underlying secondary transmission can be dependent on environmental factors potentially associated with climate and season parameters. Seasonal variation may also reflect more effective transmission during certain periods of the year due to hygrometry and ambient temperature as shown for influenza virus transmission. In conclusion, we did not observe any seasonality in the occurrence of MERS. There were higher numbers of cases in the winter and the summer of 2015 and the spring of 2017. Any seasonal variation may reflect cyclic variation in the circulation of MERS-CoV in animals or the variation in the human-camel interactions as people became aware of this connection. It is important to note that healthcare associated transmissions of MERS-CoV is the hall mark of MERS disease [5].

Financial support

All authors have no funding.

Conflicts of interest

All authors have no conflict of interest to declare.

References

- 1.Dowell S.F., Ho M.S. Seasonality of infectious diseases and severe acute respiratory syndrome-what we don't know can hurt us. Lancet Infect Dis. 2004;4:704–708. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(04)01177-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.World Health Organization (WHO) WHO; 2017. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)http://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Saudi Ministry of Health Saudi ministry of health-MERS. https://www.moh.gov.sa/en/CCC/PressReleases/Pages/default.aspx n.d.

- 4.World Health Organization Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): summary of current situation, literature update and risk assessment–as of 5 February 2015 2015. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/mers-5-february-2015.pdf

- 5.Al-Tawfiq J.A., Auwaerter P.G. Healthcare-associated infections: the hallmark of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) with review of the literature. J Hosp Infect. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2018.05.021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kasem S., Qasim I., Al-Doweriej A., Hashim O., Alkarar A., Abu-Obeida A. The prevalence of Middle East respiratory Syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) infection in livestock and temporal relation to locations and seasons. J Infect Public Health. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.jiph.2018.01.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Aly M., Elrobh M., Alzayer M., Aljuhani S., Balkhy H. Occurrence of the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) across the gulf corporation council countries: four years update. PLoS One. 2017;12 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0183850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]