Abstract

A case of acquired skin fragility syndrome associated with hepatic disease in a 9-year-old, spayed female, domestic shorthair cat is described. The cat was admitted to the veterinary hospital of the University of São Paulo (Brazil) with a 6-week history of vomiting, inappetence and weight loss. Remarkable signs were weakness, lethargy and profound jaundice that had been present for 10 days according to the owner. On completion of the physical examination, when the cat was gently manipulated for blood collection the thoracic limb and interscapular skin tore. Liver enzymes and bilirubin levels were all above the normal range. On histological examination of skin and liver, Masson's trichrome stain showed collagen fibre alteration and major hepatocyte abnormalities. Findings were consistent with feline skin fragility syndrome associated with cholangiohepatitis and hepatic lipidosis.

A 2.5 kg, 9-year-old spayed female domestic shorthair cat was admitted to the Veterinary Teaching Hospital of the College of Veterinary Medicine and Animal Sciences, University of São Paulo – Brazil, with a 6-week history of vomiting, inappetence and weight loss. Other presenting signs were weakness, lethargy and jaundice (Fig 1) of 10 days duration. The cat lived exclusively indoors and it was fed commercially prepared dry cat food. The cat had not been evaluated by any other veterinarian priory and thus it had not received any previous treatment.

Fig 1.

Profound jaundice in a cat with skin fragility syndrome associated with cholangiohepatitis and lipidosis.

On clinical examination by the veterinarian body temperature, heart rate and respiratory rate were within normal reference range. However, the cat was found to be dehydrated (7% estimated dehydration), lethargic and profoundly icteric.

After completion of the physical examination the cat was then prepared for blood collection. At this point, and exactly whilst being held and petted by the owner, its skin tore at the interscapular region leading to a 4.5 inches skin flap with muscle exposure but without bleeding (Fig 2). A detailed examination of the skin revealed a general thinning in the absence of scarring and hyperextensibility. On further questioning, the owner reported that the cat had never been affected by any dermatological disease or skin lacerations.

Fig 2.

Interscapular region showing a skin flap. Post-mortem picture.

Given the cat's poor clinical conditions, 0.9% saline solution continuously infused intravenously was immediately initiated (rate infusion at 30 ml/kg/h). For this, a 24G catheter was inserted into the left thoracic limb cephalic vein with no difficulties. However, during infusion the skin of the region in which the catheter had been inserted tore (Fig 3).

Fig 3.

Thoracic limb region after preparation for fluid therapy showing a small area of tearing skin. Ante-mortem picture.

Routine haematology was performed, revealing a complete blood count (CBC) with low packed cell volume (Table 1). Serum biochemistry findings included an increased activity of the liver enzymes alanine aminotransferase (ALT), alkaline phosphatase (ALP), gamma-glutamyl transferase (GGT) and aspartate aminotransferase (AST). Bilirubin levels were above normal reference range whereas serum glucose levels were within normal reference range (Table 2). Blood tests for feline leukaemia virus (FeLV) and feline immunodeficiency virus were negative.

Table 1.

Haematological findings in a cat with skin fragility syndrome associated with cholangiohepatitis and lipidosis.

| CBC | Patients value | Reference range |

|---|---|---|

| White blood cells | 12,800 cells/μl | 5500–16,500 cells/μl |

| Mature neutrophils | 11,648 cells/μl | 3000–13,000 cells/μl |

| Lymphocytes | 348 cells/μl | 1200–9000 cells/μl |

| Monocytes | 768 cells/μl | 0–750 cells/μl |

| Haematocrit | 25% | 25–45% |

| Red blood cells | 5×106 cells/μl | 5–10×106 cells/μl |

| Haemoglobin | 10.1 g/dl | 9.3–16 g/dl |

| Mean corpuscular volume | 50 fl | 37–61 fl |

| Mean corpuscular haemoglobin | 20.2 pg | 11–21 pg |

| Mean corpuscular haemoglobin concentration | 38 g/dl | 30–38 g/dl |

| Platelets | 500,000 | 300,000–800,000 |

| Reticulocyte count | 0 | 0 |

Table 2.

Biochemistry screen in a cat with skin fragility syndrome associated with cholangiohepatitis and lipidosis.

| Chemistry screen | Patients value | Reference range |

|---|---|---|

| Urea nitrogen | 50 mg/dl | 10–40 mg/dl |

| Creatinine | 1.1 mg/dl | 1.5–2 mg/dl |

| Sodium | 142 mmol/l | 146–157 mmol/l |

| Potassium | 3.5 mmol/l | 3.5–5.0 mmol/l |

| Glucose | 83 mg/dl | 80–110 mg/dl |

| Total protein | 7.4 g/dl | 5.5–8.5 g/dl |

| Albumin | 3 g/dl | 2.7–4.6 g/dl |

| AST | 415 U/l | 1–40 U/l |

| ALT | 446 U/l | 30–70 U/l |

| ALP | 3095 U/l | 20–70 U/l |

| GGT | 23 U/l | 1–5 U/l |

| Total bilirubin | 24.3 mg/dl | 0.15–0.25 mg/dl |

A probable diagnosis of acquired skin fragility associated with hepatic disease was made based on the physical examination and supported by biochemistry findings indicative of ongoing severe liver disease. Due to the cat's deteriorating condition despite supportive therapy, and considering the poor prognosis of the disease, the cat was euthanased on the request of the owner who permitted a post-mortem examination.

Histological examination of the liver revealed severe degeneration of hepatocytes with large lipid droplets accumulation in the cytoplasm, necrosis and ductular proliferation. It was also revealed a moderate inflammatory infiltrate of neutrophils and lymphocytes combined with a mild degree of fibrosis. There were ductular microabscesses and green pigment granules in some hepatocytes; the latter suggestive of biliary pigments. Some ducts exhibited basophilic mucinous material containing intraluminally degenerated neutrophils. These findings are morphologically consistent with hepatic lipidosis associated with chronic cholangiohepatatis (Fig 4).

Fig 4.

Liver: severe and diffuse macrovesicular degeneration of hepatocytes; hepatocytes apoptosis in zone 1; duct proliferation with moderate inflammatory infiltrated of lymphocytes (arrow), neutrophils. A discrete fibrosis is also seen (haematoxylin and eosin (H&E) ×10).

Histological examination of the skin revealed an atrophied (monolayer keratinocytes) epidermis with a moderate orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis. The dermis showed reduced and fragmented collagen fibres and atrophic follicles (Fig 5). Masson's trichrome stain confirmed alterations as collagen fibres presented with segmental red staining when polarised light was focused (Fig 6) (normal collagen fibres stain blue). These findings were consistent with a dysplastic form of dermal connective tissue that corresponds well to the morphological aspects of skin fragility.

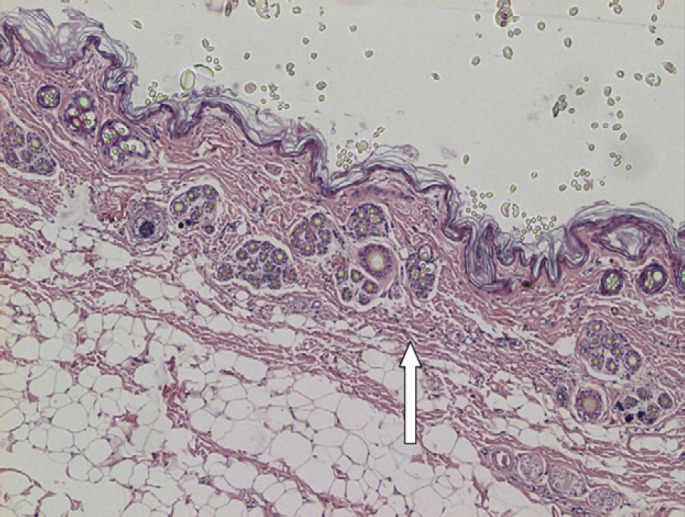

Fig 5.

Skin: atrophic epidermis (monolayer of keratinocytes) with moderate orthokeratotic hyperkeratosis. Dermis presenting reduced collagen fibres showing fragmentation and atrophic follicules (arrow). Panniculus are prominent in comparison with attenuated collagen fibres (H&E ×4).

Fig 6.

Masson's trichrome staining: collagen affected fibres coloured red in contrast to the diffuse blue staining of the normal fibre (×20).

Histological examination of the remaining tissues was unremarkable.

Feline skin fragility syndrome (FSFS) is a rare disorder of multifactorial causes characterised by extreme cutaneous fragility in the absence of hyperextensiblity. 1–4 It constitutes one of the most devastating cat skin disorders due not only to the serious consequences of a tearing thin skin but because affected cats are often quite debilitated making any form of treatment very risky. It is commonly reported in association with severe diseases (eg, hyperadrenocorticism, diabetes mellitus, cholangiocarcinoma, cholangiohepatitis, lipidosis) or excessive use of megestrol acetate or other progestational compounds. 4–6

The exact pathogenesis regarding the cutaneous abnormalities seen in affected patients remains unknown but it is believed to be related to an effect of glucocorticoids on collagen production. 5–7

In the present case, acquired skin fragility was initially suspected due to the skin tearing during physical examination and it was later confirmed by the histological evaluation of the skin. On subsequent investigation of causes and possible associated diseases, the owner reported that the cat had not received glucocorticoids or any progestational compound previously which eliminated the possibility of an iatrogenic cause. Besides, clinical history and the results of laboratory examinations were incompatible with hyperadrenocorticism or diabetes mellitus. This was later confirmed by the normality of pancreas, pituitary and adrenals on histopathological analysis. However, increased activity of ALT, ALP, AST, GGT and bilirubin suggested an associated liver disease which was confirmed by the hepatic abnormalities associated with cholangiohepatitis and lipidosis seen on necropsy.

Hepatic disorders are relatively common in cats 8 despite their relatively difficult diagnosis mainly due to the chronic, vague and non-specific clinical signs. 9 Among them, inflammatory liver diseases such as cholangiohepatitis (acute or chronic) and lymphocytic portal hepatitis have frequent occurrence being second only to hepatic lipidosis. 10 Other non-inflammatory liver diseases commonly reported in cats are neoplasia (mainly lymphoma) and congenital portosystemic shunts. 9

While cholangiohepatitis has been observed in association with chronic pancreatitis and inflammatory bowel disease, 11 occurring sometimes as a component of the inflammatory disease of the intestines or pancreas, 12 this was not seen in this case as pancreas as well as small and large bowel presented normal. In a previous study 80% of the cats with cholangiohepatitis had concurrent inflammatory bowel disease whilst 50% had at least mild inflammation of the pancreas. 13

The exact cause of chronic cholangiohepatitis remains unknown, existing speculations particularly in terms of a progression of an acute form or secondary to an immune-mediated possibly resulting of an initial bacterial insult. Other causes currently cited are feline coronavirus, FeLV, toxoplasma and liver flukes. 9

As to the lipidosis, due to the long term anorexia and the deteriorating clinical conditions showed by the cat, we believe it is probably secondary to cholangiohepatitis.

Skin fragility syndrome is a rare condition. Two cases of FSFS associated with hepatic disease were published so far. 3,6

In the present case, skin fragility was observed during physical examination and catheterisation and until that moment there was no reference to any previous dermatological disease or skin lacerations. This is in accordance with the fact that acquired skin fragility (as opposed to congenital cutaneous asthenia) tends to be recognised in middle age to old animals that have not had a previous history of dermatological diseases. 5,6

It is important to note that exactly as it was seen in this case, the fragile skin of a FSFS cat easily tears even as consequence of normal handling but it rarely bleeds upon tearing. Histopathological skin alterations seen in affected cases are distinctive and characterised by a thin epidermis and an atrophic dermis. Collagen fibres are typically thin and disorganised and hair follicles generally short and thin. 5,6 The cat reported in this case had similar epidermic and dermic alterations.

Although associations like the one found in this case (ie, acquired skin fragility and cholangiohepatitis, with hepatic lipidosis associated) cannot state a causal relationship, it draws attention to the importance of taking into consideration hepatic diseases when dealing with cats presented with skin fragility.

References

- 1.Butler W.F. Fragility of the skin in a cat, Res Vet Sci 19, 1975, 213–216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hubert B. Asthenie cutanée (maladie Ehrles-Danlos) et néphfrose lipoidique chez um Chat, Point Vet 15, 1983, 37–39. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Regnier A., Pieraggi M.T. Abnormal skin fragility in a cat with cholangiocarcinoma, J Small Anim Pract 30, 1989, 419–423. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fernandez C.J., Scott D.W., Erb H.N., Minor R.R. Staining abnormalities of dermal collagen in cats with cutaneous asthenia or acquired skin fragility as demonstrated with Masson's trichrome stain, Vet Dermatol 9, 1998, 49–54. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Scott D.W., Miller W.H., Griffin C.E. Miscellaneous skin disease: Feline acquired skin fragility, Muller and Kirk's small animal dermatology, 6th edn, 2001, WB Saunders: Philadelphia, 1170–1173. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Trotman T.K., Mauldin E., Hoffmann V., Del Piero F., Hes R.S. Skin fragility syndrome in a cat with feline infectious peritonitis and hepatic lipidosis, Vet Dermatol 18, 2007, 365–369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Helton-Rhodes K., Wallace M., Beer K. Cutaneous manifestations of feline hyperadrenocorticism. Ihrke P.J. Advances in veterinary dermatology Vol. 2, 1993, Pergamon Press: New York, 391–396. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schrek M.A., Center S.A. Toxic, metabolic, infectious and neoplastic diseases of the liver. Ettinger S.J., Feldman E.C. Textbook of veterinary internal medicine, 6th edn, 2005, Elsevier-Saunders: St Louis, 1464–1478. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Stonehewer J. The liver and pancreas. Chandler E.A., Gaskell C.J., Gaskell R.M. Feline medicine and therapeutics, 3rd edn, 2007, Oxford, Blackwell Publishing, 435–453. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Edwards M. Feline cholangiohepatitis, Compendium 26, 2004, 855–861. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Weiss D.J., Gagne J.M., Armstrong P.J. Relationship between inflammatory hepatic disease and inflammatory bowel disease, pancreatitis and nephritis in cats, J Vet Med Assoc 42, 1996, 2036–2048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harkin K. Diseases of the hepatobiliary system. In: Morgan R, ed. Handbook of small animal practice. 5th edn. 2008: 416–32. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bunch S.E. Hepatobiliary diseases in the cat. Couto C.G., Nelson R.W. Small animal internal medicine, 1st edn, 1998, Mosby: St Louis, 510–528. [Google Scholar]