Abstract

Serum samples from 214 Swedish cats with no signs of infectious disease were analysed for the presence of antibodies against Chlamydophila felis (Cp felis), while 209 of these were also analysed for feline coronavirus (FCoV) antibodies. The prevalence of antibodies against Cp felis was 11%, with no significant difference between purebred and mixed breed cats. The overall prevalence of antibodies against FCoV was 31%, significantly higher among pure breed cats (65%) than among mixed breed cats (17%). A high proportion of cats with antibodies against FCoV had relatively high antibody titres, and was therefore likely to be shedding FCoV in faeces. For Cp felis, the majority of seropositive animals had relatively low antibody titres, and the risk of these animals infecting others is not known.

Feline coronavirus (FCoV) is a common infectious agent in multiple cat households. It is primarily present in the intestinal tract of infected cats, usually causing no clinical signs. In kittens, FCoV has been associated with diarrhoea (Addie and Jarrett 1992a). The virus is transmitted mainly by faecal–oral transmission. Although infections with FCoV usually are subclinical, mutant strains occasionally cause clinically manifest feline infectious peritonitis (FIP) (Vennema et al 1998). FIP is more common in cats younger than 2 years than in older cats (Addie and Jarrett 1992a, Foley et al 1997a), and is a common cause of death in kittens 3–5 months old (Ström Holst and Karlstam 2002). The seroprevalence of FCoV varies considerably between different populations, depending on factors such as breed, management and geographical localisation (Horzinek and Osterhaus 1979, Sparkes et al 1992, Addie and Jarrett 1992b). A correlation between the shedding of FCoV and antibody titre has been demonstrated (Addie and Jarrett 2001), as well as between shedding frequency and shedding intensity (Horzinek and Lutz, 2001).

Chlamydophila felis (Cp felis) is an intracellular bacterium causing mainly conjunctivitis in cats. Conjunctivitis is sometimes seen in kittens younger than 2 weeks, but clinical disease is most common after weaning, at 6–12 weeks of age (Pedersen 1991). The organism can also be isolated from cats without clinical signs (Gruffydd-Jones et al 1995). Transmission is thought to occur mainly by direct contact between cats. Based on seroprevalence, infection was shown to be endemic in some feral cat and farm cat colonies (Wills et al 1988). Serology indicates exposure but is of limited use in predicting which cats are shedding Cp felis, although seronegative cats are most likely not infectious (McDonald et al 1998).

The present study was undertaken to determine the prevalence of antibodies to FCoV and Cp felis among Swedish cats without signs of infectious disease.

Serum samples were collected by venepuncture from cats visiting 17 veterinary clinics in Sweden. Serum was stored at −20°C until analysis. The cat owners gave their written consent to the sampling, in accordance with the approval for this study from the ethical committee for animal research and from the Swedish Board of Agriculture. To be included in the study, the cats had to be free from clinical signs of infectious diseases and not vaccinated against Chlamydophila felis. Samples were taken from 214 cats, 147 mixed breed cats and 64 purebred (most common breeds: 28 Birman, eight Norwegian Forest cats and five Oriental Shorthair). For three cats, information regarding breed was missing. One hundred and fourteen cats (54%) were males, and 31% of the cats were neutered. The age varied from 4 months to 16 years, with a mean age of 2.5 years and median age of 1 year. For the analysis of antibodies against FCoV, samples from five mixed breed cats were missing. Antibodies against Cp felis and FCoV were analysed with indirect immunofluorescence (IFA) tests. For analysis of antibodies against Cp felis, the method described by Wills et al (1988) was used. Whole cat C psittaci inclusions grown in cycloheximide-treated McCoy cell monolayers formed the antigen. For analysis of FCoV antibodies, Felis catus whole foetus (fwcf) cells infected with FCoV strain DF2 were used. For Cp felis, titres <1:32 were considered negative, and for FCoV, titres <1:10 were considered negative. Logistic regression (Minitab 13.1) was used to evaluate if any of the parameters: number of cats (5 or more or less than 5); age (younger than 1 year or 1 year and older); history of conjunctivitis (yes or no), breed (purebred or mixed breed); sex (male or female); or if the cats were neutered or not was predictive of seropositivity. P<0.05 was set as the level of statistical significance.

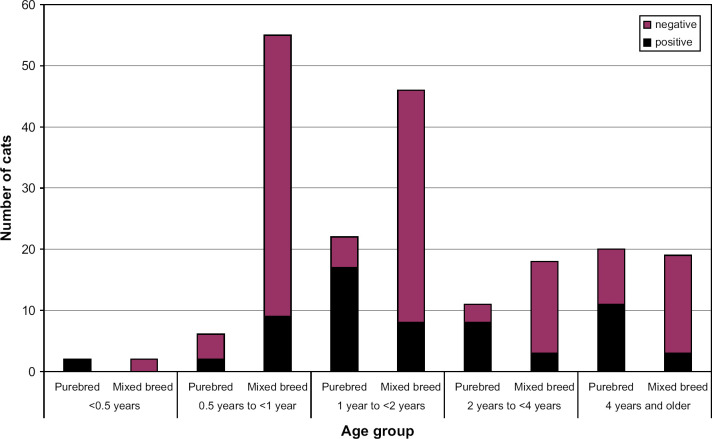

The prevalence of antibodies against FCoV among all cats was 31.1%. The seroprevalence was significantly higher among purebred cats (65%) than among mixed breed cats (17%), and significantly higher if the cats lived in groups of at least five (71%) than if the cats lived in groups of less than five (29%) (Table 1). Seventy-five percent of the seropositive cats had antibody titres of 1:320 or higher (Fig 1).

Table 1.

Seroprevalence (%) of FCoV

| Parameter | 0 | 1 |

|---|---|---|

| 0=mixed breed, 1=purebred | 17 (n=144) | 65 (n=64) * |

| 0=age <1 year, 1=age 1 year and older | 27 (n=114) | 36 (n=88) |

| 0=group of <5, 1=group of 5 or more | 29 (n=129) | 71 (n=24) * |

| 0=male, 1=female | 28 (n=109) | 35 (n=99) |

| 0=not neutered, 1=neutered | 30 (n=141) | 33 (n=64) |

Indicates statistically significant difference within row. The total number of cats within each group is given within parentheses.

Fig 1.

Distribution of cats with antibodies against FCoV (n=65).

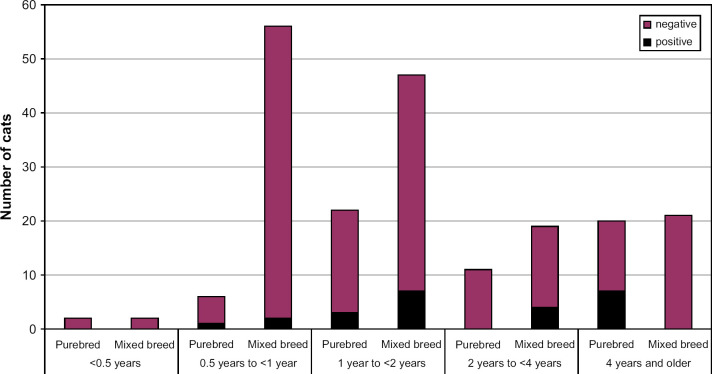

The overall prevalence of antibodies against Cp felis was 11%, with no significant difference between purebred and mixed breed cats (Table 2). There was neither significant difference in seroprevalence between cats living in groups of at least five cats and cats living in smaller groups, nor was there any significant difference in seroprevalence for Cp felis between cats with a history of conjunctivitis and cats without previous signs of conjunctivitis. Seventy-five percent of the seropositive cats had antibody titres 1:128 or lower (Fig 2).

Table 2.

Seroprevalence (%) of Chlamydophila felis

| Parameter | 0 | 1 |

|---|---|---|

| 0=mixed breed, 1=purebred | 9 (n=149) | 18 (n=62) |

| 0=age <1 year, 1=age 1 year and older | 9 (n=116) | 14 (n=91) |

| 0=group of <5, 1=group of 5 or more | 14 (n=132) | 8 (n=24) |

| 0=male, 1=female | 10 (n=114) | 13 (n=99) |

| 0=not neutered, 1=neutered | 11 (n=144) | 11 (n=66) |

| 0=no history of conjunctivitis, 1=history of conjunctivitis | 11 (n=189) | 15 (n=13) |

There are no significant differences within row. The total number of cats within each group is given within parentheses.

Fig 2.

Distribution of cats with antibodies against Chlamydophila felis (n=24).

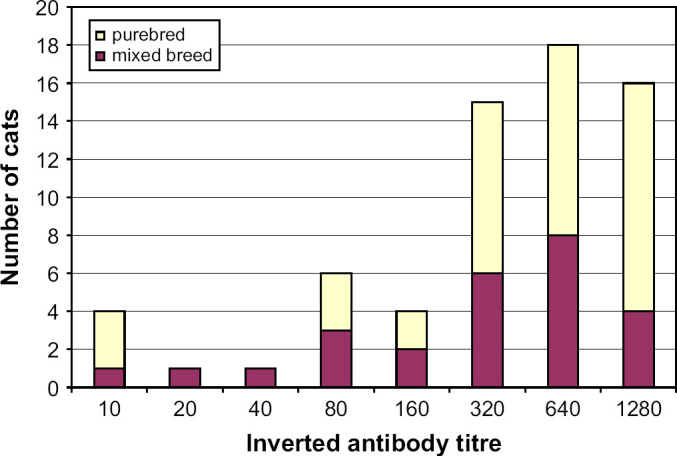

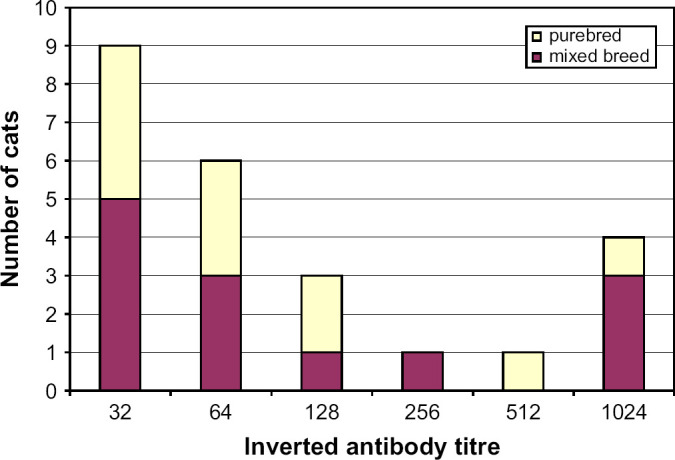

There was no significant difference in seroprevalence for FCoV or Cp felis between cats younger than 1 year and older cats, between male and female cats or between neutered and intact cats (Tables 1 and 2). The age distribution of purebred and mixed breed cats as well as the proportions of seropositive cats for each age group is shown in Figs 3 and 4.

Fig 3.

Distribution of cats and the proportions seropositive to FCoV among different age groups.

Fig 4.

Distribution of cats and the proportions seropositive to Chlamydophila felis among different age groups.

The present study shows that the seroprevalence of FCoV among cats in Sweden is of the same magnitude as in the UK (Addie and Jarrett 1992b, Sparkes et al 1992). Seroprevalence is higher in purebred cats than in mixed breed cats, and higher in cats that are kept in groups of at least five than in cats kept in smaller groups. This is probably a reflection of the dynamics of FCoV-infection in cats. Most cats get transiently infected (Addie and Jarrett 2001), and recovered transiently infected cats can be re-infected with the same or a different strain (Foley et al 1997b, Addie et al 2003). This maintains infection with FCoV in groups of cats, especially when sharing litter trays. Purebred cats are frequently kept indoors and it is reasonable to assume that faecal–oral transmission is more effective when cats share litter trays than when allowed to bury their faeces outdoors, leading to a higher seroprevalence among purebred cats. Furthermore, kittens shed higher amounts of FCoV than adult cats do (Pedersen et al 2004), leading to potentially high viral loads in infected catteries.

The majority of the seropositive cats had titres of 1:320 or higher, and these cats can also be suspected of shedding FCoV, as there is a correlation between FCoV shedding and high antibody titres (Addie and Jarrett 2001). The high seroprevalence among purebred cats thus stresses the necessity of precautions against re-infection for breeders of FCoV-free cats, eg, when introducing new cats in the household, or when mating with cats from other breeders (Ström Holst, 2002).

The smaller proportion of cats with antibodies against Cp felis may be explained by the fact that disease transmission occurs mainly via direct contact between cats or by fomites (Sykes 2005). A higher seroprevalence of Cp felis among younger cats, which has been described previously (Wills et al 1988), was not present in this study. This might be due to the limited number of young kittens in the present study. The relationship between antibody titres and detection of Cp felis has not been extensively studied. In one study, Cp felis was detected in samples from 41% of the cats with antibody titres ≥320, and to a lesser extent from cats with lower antibody titres (McDonald et al 1998). Thus, the majority of the cats with antibodies against Cp felis in the present study might not have been contagious at the time of sampling. In humans, it has been shown that detectable levels of IgG antibodies against Chlamydia trachomatis persist for several years in asymptomatic subfertility patients, and reactivation or re-infection does not seem to be responsible for this (Gijsen et al 2002). High antibody titres in cats against Cp felis can persist for more than a year, but it is not known whether this represents antibodies with a long half-life, or a persistent infection (Wills 1986). Further studies are needed to establish to what extent clinically healthy cats with antibodies against Cp felis are also carriers of the organism. Such carriers could have the potential of reactivating the infection, leading to clinical signs and risking infection of other animals.

FCoV is a widespread virus, especially among purebred Swedish cats. Breeders of uninfected cats must be careful if they want to avoid introducing the virus into the group. Antibodies against Cp felis are equally prevalent in both mixed breed and purebred cats, and the infection should, therefore, be considered in cases of conjunctivitis in both these groups.

Acknowledgements

The present study was financed by the Swedish Research Fund for Cats and the AGRIA Insurance Company Research Fund. The authors acknowledge the staff of all the animal hospitals and clinics that collected the samples.

References

- Addie D.D., Jarrett O. A study of naturally occurring feline coronavirus infection in kittens, Veterinary Record 130, 1992a, 133–137. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addie D.D., Jarrett O. Feline coronavirus antibodies in cats, Veterinary Record 131, 1992b, 202–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addie D.D., Jarrett O. Use of a reverse-transcriptase polymerase chain reaction for monitoring the shedding of feline coronavirus by healthy cats, Veterinary Record 148, 2001, 649–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Addie D.D., Schaap I.A.T., Nicolson L., Jarrett O. Persistence and transmission of natural type I feline coronavirus infection, Journal of General Virology 84, 2003, 2735–2744. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley J.E., Poland A., Carlson J., Pedersen N.C. Risk factors for feline infectious peritonitis among cats in multiple-cat environments with endemic feline enteric coronavirus, Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 210, 1997a, 1313–1318. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foley J.E., Poland A., Carlson J., Pedersen N.C. Patterns of feline coronavirus infection and fecal shedding from cats in multiple-cat environments, Journal of the American Veterinary Medical Association 210, 1997b, 1307–1312. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gijsen A.P., Land J.A., Goossens V.J., Slobbe M.E.P., Bruggeman C.A. Chlamydia antibody testing in screening for tubal factor subfertility: the significance of IgG antibody decline over time, Human Reproduction 17, 2002, 699–703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gruffydd-Jones T.J., Jones B.R., Hodge H., Rice M., Gething M.A. Chlamydia infection in cats in New Zealand, New Zealand Veterinary Journal 43, 1995, 201–203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horzinek M.C., Osterhaus A.D.M.E. Feline infectious peritonitis: a worldwide serosurvey, American Journal of Veterinary Research 40, 1979, 1487–1492. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horzinek M.C., Lutz H. An update on feline infectious peritonitis, Veterinary Sciences Tomorrow Issue 1, 2001,(www.vetscite.org/issue1/reviews/txt_index_0800.htm).

- McDonald M., Willett B.J., Jarrett O., Addie D.D. A comparison of DNA amplification, isolation and serology for the detection of Chlamydia psittaci infection in cats, Veterinary Record 143, 1998, 97–101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen N.C. Common infectious diseases of multiple-cat environments. Pedersen N. Feline husbandry, diseases and management in the multiple-cat environment, 1991, American Veterinary Publications, Inc: Goleta, 163–288. [Google Scholar]

- Pedersen N.C., Sato R., Foley J.E., Poland A.M. Common virus infections in cats, before and after being placed in shelters, with emphasis on feline enteric coronavirus, Journal of Feline Medicine and Surgery 6, 2004, 83–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sparkes A.H., Gruffydd-Jones T.J., Harbour D.A. Coronavirus serology in healthy pedigree cats, Veterinary Record 131, 1992, 35–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ström Holst B. Disease transmission by mating or artificial insemination in the cat: concerns and prophylaxis. Concannon P.W., England G., Verstegen J., Linde-Forsberg C. Recent advances in small animal reproduction. International Veterinary Information Service (IVIS), 2002, www.ivis.org, A1229.0902 [Google Scholar]

- Ström Holst B, Karlstam E. (2002) Causes of mortality in kittens 0–20 weeks old: a retrospective study. Proceedings of the 3rd EVSSAR European Congress on reproduction in companion, exotic and laboratory animals, 176–177.

- Sykes J.E. Feline chlamydiosis, Clinical Techniques in Small Animal Practice 20, 2005, 129–134. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vennema H., Poland A., Foley J., Pedersen N.C. Feline infectious peritonitis viruses arise by mutation from endemic feline enteric coronaviruses, Virology 243, 1998, 150–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wills JM. (1986) Chlamydial infection in the cat. PhD thesis, University of Bristol.

- Wills J.M., Howard P.E., Gruffydd-Jones T.J., Wathes C.M. Prevalence of Chlamydia psittaci in different cat populations in Britain, Journal of Small Animal Practice 29, 1988, 327–339. [Google Scholar]