Abstract

Background: The etiologic agent of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a recently identified, positive single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) coronavirus (SARS-CoV). Little is known about the dynamic changes of the viral replicative form in SARS cases. Objectives: Evaluate whether SARS-CoV can infect and replicate in peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of infected persons and reveal any dynamic changes to the virus during the course of the disease. Study design: Peripheral blood mononuclear cells collected from SARS cases infected by the same infectious source were tested for both negative-stranded RNA (minus-RNA, “replicative intermediates”) and positive-stranded RNA (genomic RNA) of SARS-CoV during the course of hospitalization by reverse transcription-polymerase chain reaction (RT-PCR). Results: SARS-CoV minus-RNA was detected in PBMCs from SARS patients. The viral replicative forms in PBMCs were detectable during a period of 6 days post-onset of the disease, while the plus-RNA were detectable for a longer period (8–12 days post-onset). Conclusions: SARS-coronavirus can infect and replicate within PBMCs of SARS patients, but viral replication in PBMCs seems subject to self-limitation.

Abbreviations: BNI, Bernhard-Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine, Hamburg, Germany; BSL3, biosafety level 3; CoV, coronavirus; MHV, mouse hepatitis virus; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; minus-RNA, replicative negative-stranded RNA; plus-RNA, positive-stranded genomic RNA; RT, reverse transcription; SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; SCA, sodium citrate anticoagulant

Keywords: Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), SARS-coronavirus, Replicative negative-stranded RNA, Peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs)

1. Introduction

It has been confirmed that the pathogen for severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a novel coronavirus termed SARS-coronavirus (SARS-CoV). It is a positive single-stranded RNA (ssRNA) virus, classified within the order Nidovirales, family Coronaviridae, genus Coronavirus. Although the virus has been identified and its genomic sequences analyzed (Lee et al., 2003, Marra et al., 2003, Tsang et al., 2003, Poutanen et al., 2003), little is known about its biological features.

Cells infected with mouse hepatitis virus contain both positive- and negative-stranded RNAs of this virus (MHV, a member of the genus Coronavirus). It is generally accepted that the minus-RNAs are the principal templates of positive-stranded RNA synthesis during MHV infection (Baric and Yount, 2000). For SARS-CoV there are no reports concerning the existence of replicative negative-stranded RNA in SARS patients. In order to evaluate (i) whether SARS-CoV can infect peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMCs) of infected persons, (ii) whether the virus can replicate in their PBMCs, and (iii) to reveal any dynamic changes to the virus during the course of the disease, we carried out follow-up investigations on the plus- and minus-RNA forms in SARS patients.

2. Methods

2.1. Patients and samples

The patients reported here were infected with SARS-CoV from the same source. Patient 1 (male, 47-year-old), Patient 2 (female, 49-year-old) and Patient 3 (female, 53-year-old) were three of six members of a single family. On 12 April 2003, they traveled from Hangzhou to Wuhan City to meet other members of the family. Among them, the eldest sister, who was from Beijing, had a fever and a cough that had started on 11 April but the family members did not suspect their eldest sister being infected by SARS-CoV, and took no protective measures. After the family gathering, the eldest sister returned to Beijing, where she was soon admitted to hospital and diagnosed as a definite SARS case on 15 April. The three family members reported here came back to Hangzhou City on 14 April. The 53-year-old sister (Patient 3) began to show SARS-associated symptoms (fever, cough, pain in chest, etc.) on 17 April, as did the other two on 18 April. On 19 April all three patients were admitted to the special ward of a hospital designed for the isolation of infectious diseases. The strict containment conditions these three patients, infected in Wuhan City, were subjected to helped to interrupt the further spreading of their infection.

On the day of admission to hospital and every 1 or 2 days thereafter, 5 ml of venous blood (SCA) were collected from each of the three patients. The isolation of PBMCs and the extraction of RNA were performed in a laboratory of biosafety level 3 (BSL 3).

2.2. PBMCs isolation

PBMCs were isolated after adding an equal volume of lymphocyte separation medium to 5 ml of freshly collected blood, washed twice with and suspended in 250 μl of normal saline solution (0.85% NaCl).

2.3. RNA extraction

RNA was extracted from blood plasma (250 μl), from the washed PBMCs and from pharyngeal gargling solutions, using Trizol reagent, and processed according to the manufacturer’s instructions (Gibco BRL).

2.4. cDNA synthesis

Reverse transcription (RT) was carried out by using 100 U of SuperScript II RNase H− reverse transcriptase and 4 μl of its 5× first-strand buffer (Invitrogen), 1 μl of 10 mM dNTPs mix, 2 μl of 0.1 M DTT, 1 μl of 20 pmol/μl primer, 5 μl of the extracted RNA and 6 μl of distilled water, made up to a volume of 20 μl. RT reactions were performed at 42 °C for 50 min. The BNIoutAs primer (antisense) was used for cDNA synthesis from the plus genomic RNA of SARS-CoV, while the BNIoutS2 primer (sense) was used for cDNA synthesis from the minus-RNA of SARS-CoV. Sequences of primers used in RT-reaction and the following PCR (primer sets BNIoutS2/BNIoutAs and BNIinS/BNIinAs) were recommended by the Bernhard-Nocht Institute (BNI) for Tropical Medicine, Hamburg, Germany (Bernhard-Nocht Institute, 2003).

2.5. Nested-polymerase chain reaction (nested-PCR)

cDNAs synthesized with primer BNIoutAs (antisense) or primer BNIoutS2 (sense), respectively, were used as templates for detecting plus- or minus-RNA. For the first round of amplification, reactions (50 μl total volume) contained 5 μl of 10× PCR buffer (Invitrogen), 1.5 μl of 50 mM MgCl2, 5 μl of dNTP mix (final 200 μM each), 0.5 μl of each 20 μM primer (BNIoutS2/BNIoutAs), 0.5 μl (2.5 U) of Platinum Taq DNA polymerase (Invitrogen) and 5 μl of cDNA templates. Thermal cycle conditions were recommended by the Bernhard-Nocht Institute for Tropical Medicine, Hamburg, Germany (Bernhard-Nocht Institute, 2003), which comprised 95 °C for 3 min; 10 cycles at 95 °C for 10 s, 60 °C for 10 s (decreasing by 1 °C per cycle), 72 °C for 20 s; 40 cycles at 95 °C for 10 s, 56 °C for 10 s, and 72 °C for 20 s. Two microliters of the first PCR products were used as templates for the second round of PCR. The conditions of the second PCR were the same as used for the first one, except the primers of the first round were replaced by primer set BNIinS/BNIinAs. The first 10 cycles were the same as those applied in the first round of PCR but followed by only 25 cycles instead of 40 cycles. The PCR products were analyzed on a 2% agarose gel.

2.6. Nuclear acid sequence analysis

The PCR products were sequenced directly using a dideoxy terminator sequencing reaction (DYEnamic ET dye terminator kit, Amersham Biosciences) and an automatic DNA Analysis System (model MegaBACE 500, Amersham Biosciences).

3. Results

3.1. Detection of SARS-coronaviral positive-stranded (genomic) RNA

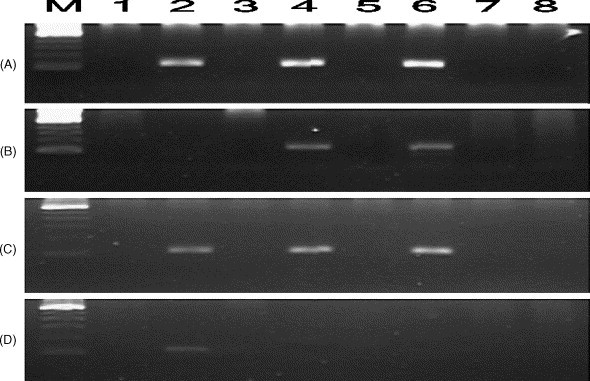

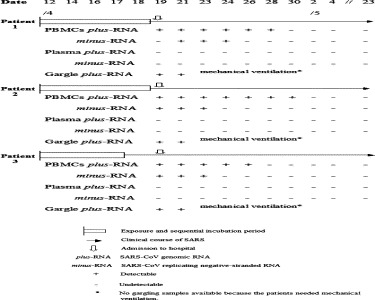

RNA extracted from plasma, PBMCs and pharyngeal gargling solutions collected from three SARS patients were reverse-transcribed into cDNA with the antisense primer BNIoutAs, followed by nested-PCR. The expected size of the amplified products was 110 bp which corresponds to the expected molecular weight of the respective sequence stretch of the RNA polymerase gene of the SARS-CoV. The genomic RNA of SARS-CoV was detected in samples collected on admission and on the days following (Fig. 1 ). The longest detectable period for the genomic RNA of SARS-CoV was 12 days post-onset of the disease (Fig. 2 ).

Fig. 1.

Electrophoresis results of RT/nested-PCR of samples collected from three SARS patients on day 1 (A, B), on day 2 (C) and on day 5 (D) following admission to hospital. (A) Detection of SARS-CoV genomic RNA using antisense primers in RT-reaction. (B–D) Detection of SARS-CoV replicative intermediate minus-RNA using sense primers in RT-reaction. M: 100 bp DNA ladder. Lanes 1 and 2: Patient 1. Lanes 3 and 4: Patient 2. Lanes 5 and 6: Patient 3. Lanes 7 and 8: normal control. Lanes with odd numbers are from plasma and lanes of even numbers from PBMCs. The expected size of plus- and minus-PCR products was 110 bp.

Fig. 2.

Timeline of events and SARS-CoV RNA markers in the course of SARS cases.

3.2. Detection of SARS-coronaviral negative-stranded (replicative intermediates) RNA

The sense primer BNIoutS2 was used for cDNA synthesis from the SARS-CoV replicative minus-RNA as template, followed by the same amplification procedures as used for the detection of the genomic plus-RNA. The minus-RNA could only be detected in PBMCs of the SARS cases (Fig. 1), but the detectable period was shorter than that for the plus-RNA (Fig. 2).

3.3. Nuclear acid sequence analysis

Nuclear acid sequence analysis of PCR products amplified from the plus- and minus-RNA showed full homology to the SARS-CoV genomic sequences (data not shown).

3.4. Dynamics of SARS-coronaviral plus- and minus-RNA during course of SARS

SARS-coronaviral minus-RNA and positive genomic RNA could appear simultaneously or alone in PBMCs, showing some characteristics in the course of SARS (Fig. 1, Fig. 2). (1) On admission to hospital, all three patients had distinct manifestations of SARS (fever, cough, chest pains). The plus-RNA was present in their pharyngeal gargling solutions and PBMCs, but not detectable in their blood plasma, while the minus-RNA form was only detected in PBMCs from Patients 2 and 3. Patient 1 was negative for the SARS-CoV minus-RNA in his PBMCs on this day. (2) One day later, the patients’ conditions became worse. Their samples were all positive for both the SARS plus- and minus-RNA. By day 5 after admission, the SARS-coronaviral minus-RNA was detectable only in PBMCs from Patient 1, the other two testing negative. By day 7, the minus-RNA in PBMCs from Patient 1 was no longer detectable (till 23 May). Results for the other two patients are shown in Fig. 2. Briefly, the detectable period of the SARS-Coronaviral replicative intermediate minus-stranded RNA in the three patients was within 6 days post-onset of the disease only, while the plus genomic RNA remained detectable for a longer period (8–12 days post-onset) (Fig. 2). Essentially, the minus-stranded RNA was detected in PBMCs only.

4. Discussion

Coronavirus replicates using genomic as well as subgenomic plus- and minus-RNA. The latter are synthesized through a discontinuous transcription process, the mechanism of which has not yet been well established (Sawicki and Sawicki, 1998, Lai and Holmes, 2001). At least five subgenomic mRNAs were detected by Northern hybridization of RNA from SARS-CoV-infected cells (Paul et al., 2003). Accordingly, SARS-CoV uses minus-RNA as some kind of ‘replicative intermediates’ during its replication cycle in cells. If minus-RNA copies of the SARS-CoV genome are detectable in samples from SARS patients, this is a reasonable indication of the presence of the replicating virus.

SARS-coronaviral replicative intermediate minus-stranded RNA, as well as the plus-stranded RNA, were detected successfully in PBMCs from all three patients. Nuclear acid sequence analyses of the PCR products showed full homology to the SARS-CoV genomic sequences. This supports the idea that SARS-coronavirus was not only passively adhering to the PBMCs but had infected the cells and replicated within them.

This is the first report showing the presence of SARS-coronavirus minus-RNA, supposed to represent replicative intermediates of its RNA, and the duration of such RNA in PBMCs during the course of SARS in patients, indicating that the virus can attack and replicate in PBMCs. It may partially help to explain why mild leukopenia or lymphopenia has been observed in SARS patients (Poutanen et al., 2003, Tsang et al., 2003). The detectable period of SARS-CoV replication in PBMCs of our three patients was less than 1 week, which suggests that viral replication in the cells is probably self-limited.

We conclude that SARS-coronavirus can not only infect but also replicate within PBMCs of SARS patients. The presence of the minus-RNA reflecting ‘replicative intermediates’ of this CoV in PBMCs is limited to within a period of 6 days post-onset of the disease, suggesting that replication in the PBMCs is subject to self-limitation. Our results raise questions requiring further studies, PBMCs being in fact mixtures of various types of cells. Finding out which type(s) of PBMCs are the main target for invasion and replication by SARS-CoV will be important in the search for molecules or receptors which can bind to the virus at the surface of these cells. This will facilitate the design and development of drugs to block the binding of SARS-CoV to susceptible cells. Also, our results should be valuable in helping to determine the administration of anti-virus and immunomodulator for SARS in clinical practice.

References

- Baric R.S., Yount B. Subgenomic negative-strand RNA function during mouse hepatitis virus infection. J. Virol. 2000;74:4039–4046. doi: 10.1128/jvi.74.9.4039-4046.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bernhard-Nocht Institute, Hamburg, Germany; 9 April 2003 at http://www.bni-hamburg.de/.

- Lai MMC, Holmes KV. In: Knipe DM, Howley PM, editors. Fields virology. 4th ed. New York: Lippincott Williams and Wilkins; 2001 [Chapter 35].

- Lee N., Hui D., Wu A. A major outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1986–1994. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marra MA, Steven JM, Jones SJM, Caroline R, Astell CR, et al. The genome sequence of the sars-associated coronavirus. Science 1 May 2003 at http://www.sciencexpress.org/ 1 May 2003/Page 1/10.1126/science.1085953.

- Paul A, Rota PA, Oberste MS, Monroe SS, et al. Characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science 1 May 2003 at http://www.sciencexpress.org/ 1 May 2003/Page 2/10.1126/science.1085952. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Poutanen S.M., Low D.E., Henry B. Identification of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Canada. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1995–2005. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030634. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawicki G.S., Sawicki D.L. A new model for coronavirus transcription. Adv. Exp. Med. Biol. 1998;440:215–219. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4615-5331-1_26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tsang K.W., Ho P.L., Ooi G.C. A cluster of cases of severe acute respiratory syndrome in Hong Kong. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1977–1985. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]