Abstract

Introduction: The recent outbreak of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) warrants the search for effective antiviral agents to treat the disease. This study describes the assessment of the antiviral potential of nitric oxide (NO) against SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) strain Frankfurt-1 replicating in African Green Monkey (Vero E6) cells.

Results: Two organic NO donor compounds, S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP) and sodium nitroprusside (SNP), were tested in a broad range of concentrations. The non-nitrosylated form of SNAP, N-acetylpenicillamine (NAP), was included as a control compound in the assay. Antiviral activity was estimated by the inhibition of the SARS-CoV cytopathic effect in Vero E6 cells, determined by a tetrazolium-based colorimetric method. Cytotoxicity of the compounds was tested in parallel.

Conclusion: The survival rate of SARS-CoV infected cells was greatly increased by the treatment with SNAP, and the concentration of this compound needed to inhibit the viral cytopathic effect to 50% was 222 μM, with a selectivity index of 3. No anti-SARS-CoV effect could be detected for SNP and NAP.

Keywords: SNAP, Nitric oxide, NO, Coronavirus, SARS-CoV, Antiviral activity

Introduction

Severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) has recently emerged as a new severe human disease, resulting globally in 774 deaths from 8098 reported probable cases (as of the 26th of September 2003). A novel member of the Coronaviridae family has been identified as the causative agent of this pulmonary disease.1 Thus far, treatment of SARS cases has been largely empirical and has usually included an antiviral agent such as ribavirin or a combination of lopinavir/ritonavir and steroids. It is however unclear whether any of these treatments were able to alter the ultimate outcome of the disease.2., 3.

During the SARS epidemic, Chen and colleagues included inhalation of NO gas in the treatment of a number of SARS patients. Medicinal NO gas, a gaseous blend of nitric oxide (0.8%) and nitrogen (99.2%), was given for three days or longer, initially at 30 ppm and then at 20 and 10 ppm on the second and third day (unpublished data). Their findings suggest not only an immediate improvement of oxygenation but also a lasting effect on the disease itself after termination of inhalation of NO.

NO is a key molecule in the pathogenesis of infectious diseases. In a variety of microbial infections, NO biosynthesis occurs through the expression of an inducible nitric oxide synthase (iNOS). This molecule has been reported to have antiviral effects against a variety of DNA and RNA viruses, including mouse hepatitis virus (MHV), a murine coronavirus.4 In a recent study, replication of two SARS-CoV isolates (FFM-1 and FFM-2) was shown to be greatly inhibited by glycyrrhizin, an active compound of liquorice roots.5 Glycyrrhizin upregulates the expression of iNOS and production of NO in macrophages.6

Although the initial global outbreak of SARS appears to have been successfully contained, SARS will remain a serious concern while there continues to be no suitable vaccine or effective drug treatment.

Materials and methods

In this study we examined the antiviral activity of nitric oxide (NO) against SARS coronavirus (SARS-CoV) isolate Frankfurt-1 (FFM-1). Two NO donor compounds, S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP, Sigma, Belgium) and sodium nitroprusside (SNP, Sigma, Belgium), were added to confluent African Green monkey (Vero E6) cells. SNAP releases NO in aqueous solutions with a half-life of approximately 4 hours.7 The non-nitrosylated form of SNAP, N-acetylpenicillamine (NAP, Sigma, Belgium) was included as a control compound in the assay. Antiviral activity and cytotoxicity measurements were based on the viability of cells that had been infected or not infected with 100 CCID50 (50% cell culture infective doses) of the SARS-CoV in the presence of various concentrations of the test compounds. Three days after infection, the number of viable cells was quantified by a tetrazolium-based colorimetric method, in which the reduction of the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-5-(3-carboxymethoxy-phenyl)-2-(4-sulfophenyl)-2H-tetrazolium (MTS) dye (CellTiter 96 AQueous One Solution kit, Promega, The Netherlands) by cellular dehydrogenases to an insoluble coloured formazan was measured in a spectrophotometer (Multiskan EX, Thermo Labsystems, Belgium) at 492 nm.8., 9. The selectivity index was determined as the ratio of the concentration of the compound that reduced cell viability to 50% (CC50 or 50% cytotoxic concentration) to the concentration of the compound needed to inhibit the viral cytopathic effect to 50% of the control value (IC50 or 50% inhibitory concentration).

The amount of NO produced by SNAP in culture medium was determined by assaying its stable end-product, NO2 − (nitrite) in a cell culture environment. Freeze-thawed cell culture samples were centrifuged at 300 g for 10 min; equal volumes (100 μl) of the sample supernatants and Griess reagent (1% sulphanilamide, 0.1% N-1-naphthylethylenediamine, 5% H3PO4) (Sigma, Belgium) were mixed and incubated for 10 min at 37 °C. The optical density at 540 nm was measured with an automated multiscan spectrophotometer. A range of sodium nitrite dilutions served to generate a standard curve for each assay.

Results and discussion

SNAP inhibited SARS-CoV replication at non-toxic concentrations (222 μM) with a selectivity index of 2.6 (Table 1 ). The NO concentration released by 222 μM SNAP is between 30–55 μM NO.

Table 1.

Activity of compounds against SARS-coronavirus in Vero E6 cell culture.

| Compound | IC50a (μM) | CC50a (μM) | Selectivity index |

|---|---|---|---|

| S-nitroso-N-acetylpenicillamine (SNAP) | 222.3 ± 83.7 | 587.7 ± 22.5 | 2.6 |

| N-acetylpenicillamine (NAP) | >500 | >500 | NC |

| Sodium nitroprusside (SNP) | >221.3 | 221.3 ± 40.5 | NC |

| Nω-nitro-L-arginine methyl ester | >500 | >500 | NC |

IC50: inhibitory concentration of compound. CC50: cytotoxic concentration. NC: not calculatable.

Mean of five assays ±SD.

No protective effect below the CC50 could be demonstrated for SNP. The difference in activity between these two NO donor compounds might be explained by a different mechanism of releasing NO. SNAP is a direct donor of NO and generates NO in aqueous solutions through hydrolysis, while SNP only releases NO after reaction with a reducing agent.10., 11., 12.

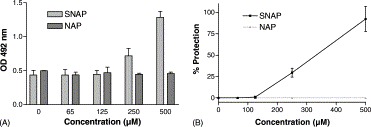

No protective effect could be obtained with N-acetylpenicillamine (NAP), which is the non-nitrosylated form of SNAP and does not release NO in solution (Figure 1 ). These results illustrate that the protective effect of SNAP is a consequence of NO release and not of a potential solitary antiviral effect of the N-acetyl-penicillamine moiety.

Figure 1.

(A) Increased survival rate of SARS FFM-1 infected Vero E6 cells by the treatment of SNAP. Optical density at 492 nm of mitochondrial activity was measured. Data are expressed as means±S.D. (B) Percent protection achieved by the compounds in SARS-CoV infected cells is calculated as follows: 100 × [(ODvirus + compound − ODsvirus control)/(ODcell control − ODsvirus control)]/(ODcompound control/ODcell control). Bars indicate SD.

In this study, we provide additional evidence that NO and NO-donors may have an antiviral effect against the SARS-CoV and we speculate that the prolonged effect of inhalation of NO gas observed earlier could be an antiviral effect of NO against SARS-CoV. Based on our results we encourage the inclusion of inhalation of NO in the treatment of SARS. NO-donors, including SNAP, have been described as potential therapeutics in the treatment of cardiovascular disease.13 To confirm the anti-SARS-CoV effect of NO gas and NO donors and before SNAP can be used in SARS treatment, additional in vivo experiments are required.

As resurgence of the SARS outbreak is a distinct possibility, the search for antivirals effective against the SARS-CoV remains an important endeavour.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by a fellowship of the Flemish Fonds voor Wetenschappelijk Onderzoek (FWO) to Leen Vijgen, and by FWO-grant G.0288.01.

Conflict of interest: No conflicting interest declared.

Corresponding Editor: Jonathan Cohen, Brighton, UK

Footnotes

Paper received at the International Society for Infectious Diseases meeting in Cancun, March 2004 and fast-tracked through review to publication.

Contributor Information

Luni Chen, Email: luni@yahoo.com.

Marc Van Ranst, Email: marc.vanranst@uz.kuleuven.ac.be.

References

- 1.Drosten C, Gunther S, Preiser W. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1967–1976. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zhaori G. Antiviral treatment of SARS: can we draw any conclusions? CMAJ. 2003;169:1165–1166. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chu C.M, Cheng V.C, Hung I.F, Wong M.M, Chan K.H, Chan K.S. Role of lopinavir/ritonavir in the treatment of SARS: initial virological and clinical findings. Thorax. 2004;59:252–256. doi: 10.1136/thorax.2003.012658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lane T.E, Paoletti A.D, Buchmeier M.J. Disassociation between the in vitro and in vivo effects of nitric oxide on a neurotropic murine coronavirus. J Virol. 1997;71:2202–2210. doi: 10.1128/jvi.71.3.2202-2210.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cinatl J, Morgenstern B, Bauer G, Chandra P, Rabenau H, Doerr H.W. Glycyrrhizin, an active component of liquorice roots, and replication of SARS-associated coronavirus. Lancet. 2003;361:2045–2046. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13615-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jeong H.G, Kim J.Y. Induction of inducible nitric oxide synthase expression by 18β-glycyrrherinic acid in macrophages. FEBS Lett. 2002;513:208–212. doi: 10.1016/s0014-5793(02)02311-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ignarro L.J, Lippton H, Edwards J.C, Baricos W.H, Hyman A.L, Kadowitz P.J. Mechanism of vascular smooth muscle relaxation by organic nitrates, nitrites, nitroprusside and nitric oxide: evidence for the involvement of S-nitrosothiols as active intermediates. Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1981;218:739–749. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pauwels R, Balzarini J, Baba M, Snoeck R, Schols D, Herdewijn P. Rapid and automated tetrazolium-based colorimetric assay for the detection of anti-HIV compounds. J Virol Methods. 1988;20:309–321. doi: 10.1016/0166-0934(88)90134-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Goodwin C.J, Holt S.J, Downes S, Marshall N.J. Microculture tetrazolium assays: a comparison between two new tetrazolium salts, XTT and MTS. J Immunol Methods. 1995;179:95–103. doi: 10.1016/0022-1759(94)00277-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bates J.N, Baker M.T, Guerra R, Jr., Harrison D.G. Nitric oxide generation from nitroprusside by vascular tissue. Evidence that reduction of the nitroprusside anion and cyanide loss are required. Biochem Pharmacol. 1991;42:157–165. doi: 10.1016/0006-2952(91)90406-u. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Marks G.S, McLaughlin B.E, Brown L.B, Beaton D.E, Booth B.P, Nakatsu K. Interaction of glyceryl trinitrate and sodium nitroprusside with bovine pulmonary vein homogenate and 10,000 × g supernatant: biotransformation and nitric oxide formation. Can J Physiol Pharmacol. 1991;69:889–892. doi: 10.1139/y91-135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kowaluk E.A, Seth P, Fung H.L. Metabolic activation of sodium nitroprusside to nitric oxide in vascular smooth muscle. J Pharmacol Exp Ther. 1992;262:916–922. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Megson I.L. Nitric oxide donor drugs. Drugs of the Future. 2000;25:701–715. [Google Scholar]