In the Lancet Infectious Diseases, Marcel Muller and colleagues1 present the first, well designed, credible, population-based seroepidemiological study of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) in Saudi Arabia.

Since the initial identification of MERS-CoV in 2012,2 up to Mar 8, 2015, WHO have reported 1082 cases of infection with this virus, 439 of which ended in death.3 Most cases were in countries in the Arabian Peninsula, with sporadic travel-related infections occurring elsewhere.

Although clusters of human-to-human transmission of MERS-CoV are well documented, transmission originates from zoonotic events, and therefore identification of the animal sources of MERS-CoV is a priority. Genetically, MERS-CoV is related to bat coronaviruses from China, Saudi Arabia, Europe, and Africa.2, 4, 5, 6 On the basis of the evidence so far, none of the bats from these countries are likely to be the reservoir for the virus.

Evidence is accumulating that dromedary camels are a natural host of MERS-CoV. Serological findings suggest that more than 90% of adult dromedaries in the Middle East and Africa are seropositive for MERS-CoV.7 The virus isolated from dromedaries has spike proteins with conserved receptor-binding domains for the human dipeptidyl peptidase-4 receptor,8, 9 and MERS-CoV has been detected in camels that were in close contact with people with Middle East respiratory syndrome.10, 11

The role of camels as a source of human infection with Middle East respiratory syndrome is controversial because many people who have the disease have had no obvious association with camels. Case-control studies that aim to define risk exposures of index patients have not yet been done, and an investigation of MERS-CoV seroprevalence in people in contact with camels yielded negative results (ie, no association was noted).8, 12, 13, 14

The study by Muller and colleagues is the first population-based, seroepidemiological investigation of MERS-CoV infection in an area where zoonotic transmission is sustained. The investigators used a cross-sectional design that tested serum samples from about 10 000 people in Saudi Arabia whose age and sex distribution was similar to that of the general population. By use of a rigorous serological testing algorithm, the investigators identified MERS-CoV antibodies in 15 (0·15%, 95% CI 0·09–0·24) of 10 009 samples from the general population. Men had a significantly higher proportion of infections (11 [0·25%] of 4341) than did women (two [0·05%] of 4378; p=0·025), and more infections were noted in central rural areas than in coastal provinces (14 [0·26%] of 5479 vs one [0·02%] of 4529; p=0·003). The investigators also obtained samples from camel shepherds and slaughterhouse workers, and showed that seroprevalence of MERS-CoV was 15–23 times higher in camel-exposed individuals than in the general population. The findings from this study suggest that young men in Saudi Arabia who have contact with camels in cultural or occupational settings are becoming infected with MERS-CoV, often without being diagnosed, and might proceed to introduce the virus to the general population in which more severe illness triggers testing for the virus and disease recognition. This hypothesis could account for cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome without previous animal exposure.

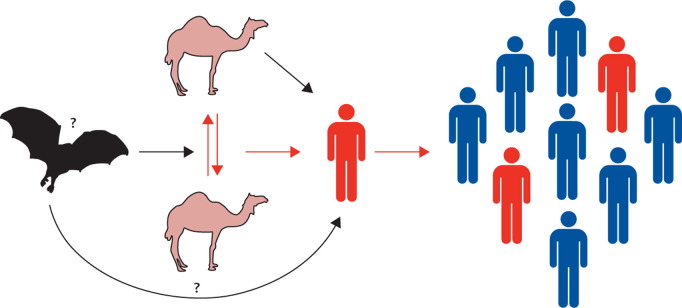

When the data from Muller and colleagues1 are put into context with those from studies in camels, a clearer picture of the epidemiology of MERS-CoV emerges (figure ). Camels seem to be a natural host for MERS-CoV and transmission within camel herds is well established.15

Figure.

The epidemiology of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus

Black arrows represent unconfirmed routes of transmission. Red arrows represent plausible routes of transmission. Red human figures represent people infected with Middle East respiratory syndrome.

However, several questions need to be resolved. The route for camel-to-human transmission is unclear, and could be from one or more of the following: direct contact with infected animals, or consumption of milk, urine, or uncooked meat—all practices that are common in affected countries in the Middle East. An intermediate host could also transmit MERS-CoV between camels and human beings. Finally, whether dromedaries are the natural reservoir or an amplifier host is a hypothesis that is open to further investigation. Muller and colleagues' study is the first step along the way to addressing these questions.

Acknowledgments

GK and MP were funded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, National Institutes of Health, and Department of Health and Human Services, USA, (contract number HHSN272201500006C) and supported by the American Lebanese Syrian Associated Charities. We declare no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Ghazi Kayali, Email: ghazi.kayali@stjude.org.

Malik Peiris, Email: malik@hku.h.

References

- 1.Muller MA, Meyer B, Corman VM. Presence of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus antibodies in Saudi Arabia: a nationwide, cross-sectional serological study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2015 doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)70090-3. published online April 9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM, Osterhaus AD, Fouchier RA. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV): summary of current situation, literature update and risk assessment. Feb 5, 2015. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/coronavirus_infections/mers-5-february-2015.pdf?ua=1 (accessed March 5, 2015).

- 4.Annan A, Baldwin HJ, Corman VM. Human betacoronavirus 2c EMC/2012-related viruses in bats, Ghana and Europe. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:456–459. doi: 10.3201/eid1903.121503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Ithete NL, Stoffberg S, Corman VM. Close relative of human Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in bat, South Africa. Emerg Infect Dis. 2013;19:1697–1699. doi: 10.3201/eid1910.130946. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Yang L, Wu Z, Ren X. MERS-Related Betacoronavirus in Vespertilio Superans bats, China. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1260–1262. doi: 10.3201/eid2007.140318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mackay IM, Arden KE. Middle East respiratory syndrome: An emerging coronavirus infection tracked by the crowd. Virus Res. 2015 doi: 10.1016/j.virusres.2015.01.021. published online Feb 2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Chu DK, Poon LL, Gomaa MR. MERS coronaviruses in dromedary camels, Egypt. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1049–1053. doi: 10.3201/eid2006.140299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hemida MG, Chu DKW, Poon LLM. MERS coronavirus in dromedary camel herd, Saudi Arabia. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1231–1234. doi: 10.3201/eid2007.140571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Haagmans BL, Al Dhahiry SH, Reusken CB. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in dromedary camels: an outbreak investigation. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:140–145. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70690-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Memish ZA, Cotten M, Meyer B. Human infection with MERS coronavirus after exposure to infected camels, Saudi Arabia, 2013. Emerg Infect Dis. 2014;20:1012–1015. doi: 10.3201/eid2006.140402. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Aburizaiza AS, Mattes FM, Azhar EI. Investigation of anti-middle East respiratory syndrome antibodies in blood donors and slaughterhouse workers in Jeddah and Makkah, Saudi Arabia, fall 2012. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:243–246. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit589. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Memish ZA, Alsahly A, Masri MA. Sparse evidence of MERS-CoV infection among animal workers living in Southern Saudi Arabia during 2012. Influenza Other Respir Viruses. 2015;9:64–67. doi: 10.1111/irv.12287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hemida MG, Al-Naeem A, Perera RAPM, Chin AWH, Poon LLM, Peiris M. Lack of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus transmission from infected camels. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015;21:699–701. doi: 10.3201/eid2104.141949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wernery U, Corman VM, Wong EYM. Acute Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection in livestock dromedaries, Dubai, 2014. Emerg Infect Dis. 2015 doi: 10.3201/eid2106.150038. published online June 2015. (accessed March 24, 2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]