Highlights

-

•

ASE guidance for patient and provider protection during echo exams in the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

•

Triaging approach for prioritizing echo exams during the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

•

Recommended imaging approach and appropriate PPE use during echo exams.

Keywords: ASE, COVID-19, Protection statement

Abbreviations: ASE, American Society of Echocardiography; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; CT, Computed tomography; MRI, Magnetic resonance imaging; POCUS, Point-of-care ultrasound; PPE, Personal protective equipment; SARS-CoV-2, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2; TEE, Transesophageal echocardiography; TTE, Transthoracic echocardiography; UAPE, Ultrasound-assisted physical examination; UEA, Ultrasound-enhancing agent

This document is endorsed by the following American Society of Echocardiography International Alliance Partners: Argentine Federation of Cardiology, Argentine Society of Cardiology, ASEAN Society of Echocardiography, Asian-Pacific Association of Echocardiography, Australasian Sonographers Association, Canadian Society of Echocardiography, Cardiovascular Imaging Society of the Interamerican Society of Cardiology (SISIAC), Chinese Society of Echocardiography, Department of Cardiovascular Imaging of the Brazilian Society of Cardiology, Echocardiography Section of the Cuban Society of Cardiology, Indian Academy of Echocardiography, Indian Association of Cardiovascular Thoracic Anaesthesiologists, Indonesian Society of Echocardiography, Iranian Society of Echocardiography, Israel Working Group on Echocardiography, Japanese Society of Echocardiography, Korean Society of Echocardiography, Mexican Society of Echocardiography and Cardiovascular Imaging (SOME-ic), National Society of Echocardiography of Mexico (SONECOM), Philippine Society of Echocardiography, Saudi Arabian Society of Echocardiography, Thai Society of Echocardiography, Venezuelan Society of Cardiology - Echocardiography Section, and Vietnamese Society of Echocardiography.

Background

The 2019 novel coronavirus, or severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus-2 (SARS-CoV-2), which results in coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), has been declared a pandemic and is severely affecting the provision of health care services all over the world.1 Health care workers are at higher risk because this virus is very easily spread, especially through the kind of close contact involved in the performance of echocardiographic studies. The virus carries relatively high mortality and morbidity risk, particularly for certain populations (the elderly, the chronically ill, the immunocompromised, and possibly pregnant women).2 Given the risk for cardiovascular complications in the setting of COVID-19, including preexisting cardiac disease, acute cardiac injury, and drug-related myocardial damage,3 echocardiographic services will likely be required in the care of patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19. Consequently, echocardiography providers will be exposed to SARS-CoV-2.

Sonographers, nurses, advance practice providers, and physicians have a duty to care for patients and are at the front lines in the battle against disease. We are at high risk, particularly when we participate in the care of patients who are suspected or confirmed to have highly contagious diseases. Although dedication to patient care is at the heart of our profession, we also have a duty to care for ourselves and our loved ones and to protect all of our patients by preventing the spread of disease. This means reducing our own risk while practicing judicious use of personal protective equipment (PPE).

The American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) is committed to the health, safety, and well-being of our members and the patients we serve. This document is provided to the ASE community as a service to help guide the practice of echocardiography in this challenging time. It represents input from a variety of echocardiography practitioners and institutions that have experience with COVID-19 or have been actively and thoughtfully preparing for it. The circumstances surrounding the outbreak are, of course, extremely dynamic, and this statement's recommendations are subject to change. We direct echocardiography practitioners to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention website for the latest updates and recommendations.4

This statement addresses triaging and decision pathways for handling echocardiography requests, as well as indications and recommended procedures to be followed for an echocardiographic assessment of cardiovascular function in suspected or confirmed COVID-19 cases. In addition, we list measures recommended to be used in the echocardiography laboratory for prevention of disease spread.

Whom to Image?

Review of Indications

Transthoracic echocardiography (TTE), stress echocardiography, and transesophageal echocardiography (TEE) should be performed only if they are expected to provide clinical benefit. The ASE and other societies have established appropriate use criteria to guide imaging.5, 6, 7, 8 Echocardiography orders are not yet subject to decision support tools, as are cardiac magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) and cardiac computed tomography (CT), but the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak highlights the need to avoid performing rarely appropriate examinations. Application of the appropriate use criteria represents the first decision point as to whether an echocardiographic test should be performed. Second, there are cases in which the indication for echocardiography is appropriate or may be appropriate, but the examination is unlikely to yield clinically important information in the short term with the added risk for potential disease transmission. There are two ways to identify these studies:

-

•

Determine which studies are “elective” and reschedule them, performing all others.

-

•

Identify “nonelective” (urgent or emergent) indications and to defer all others.

In cases considered for deferral, there is no significant risk to patients in terms of morbidity or mortality and no expected benefit in terms of avoiding the use of medical resources (such as emergency department visits or hospitalizations). These tests should be postponed.

Next, it is important to determine the clinical benefit of echocardiography for symptomatic patients whose SARS-CoV-2 status is unknown. Knowing the status of a patient allows the appropriate application of PPE and its conservation when not needed, in addition to reducing the exposure risk to echocardiography personnel.

TEE carries a heightened risk for spread of the SARS-CoV-2, because it may provoke aerosolization of a large amount of virus because of coughing or gagging that may result during the examination. TEE therefore deserves special consideration in determining when and whether this examination should be performed and under what precautions (described below). A cautious consideration of the benefit of TEE should be weighed against the risk for exposure of health care personnel to aerosolization in a patient with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 and the use of PPE. TEE should be postponed or canceled if an alternative imaging modality (e.g., off-axis TTE, ultrasound-enhancing agent with TTE) can provide the necessary information. Contrast-enhanced CT and MRI have emerged as alternatives to TEE for the exclusion of left atrial appendage thrombus before cardioversion.9 The use of these tests to avoid an aerosolizing procedure should be balanced against the risk of transporting a patient through the hospital to the computed tomographic or MRI scanner, the need to disinfect the CT or MRI room, and iodinated contrast and radiation for CT and long scan times for MRI. Some institutions have dedicated computed tomographic scanners reserved for patients with COVID-19.

Similarly, treadmill and bicycle stress echocardiography in patients with COVID-19 may lead to exposure because of deep breathing and/or coughing during exercise. These tests should generally be deferred or converted to pharmacologic stress echocardiography.

Depending on the trajectory of the outbreak, some institutions may face a crisis state with reduced availability of trained staff and/or equipment. In this setting, triage by indication may be necessary, deciding which appropriate and urgent or emergent echocardiographic studies will be performed and which will not, or deciding which will be performed first. This prioritization of indications will need to be done on a case-by-case basis, while accounting for many patient-level factors such as current indication, current clinical status, medical history, and the results of other tests. Involving referring physicians in the triage process is therefore essential.

Where to Image?

The portability of echocardiography affords a clear advantage in imaging patients without having to move them and risk virus transmission in the clinic or hospital. All forms of echocardiography (including chemical stress tests) can be performed in emergency departments, hospital wards, intensive care units, operating theaters, recovery areas, and structural heart and electrophysiology procedure laboratories, in addition to echocardiography laboratories. Identifying the optimal location for an echocardiographic study requires minimizing the risk for virus transmission but also considering monitoring capabilities and staffing of different locations. For example, patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 are placed in isolation rooms, and echocardiography performed in the patient's room can prevent transit to other areas of the hospital, risking wider exposure. However, it may not be possible to perform TEE or stress echocardiography in the room, because of staffing or insufficient monitoring equipment.

In the outpatient setting, patients should be screened for infection according to local protocols and methods for quarantine. Some institutions have set aside separate rooms and separate machines for patients with suspected or confirmed infection.

How to Image?

Protocols

Cardiac imaging is performed by a wide variety of operators using a wide variety of machines and a wide variety of protocols. Ultrasound-assisted physical examination (UAPE), point-of-care cardiac ultrasound (POCUS), critical care echocardiography, limited and comprehensive traditional TTE, TEE, and stress echocardiography all can play a role in caring for patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19. UAPE and POCUS examinations performed by the clinicians who are already caring for these patients at bedside present an attractive option to screen for important cardiovascular findings, elucidate cardiac contributions to symptoms or signs, triage patients in need of full-feature echocardiographic services, and even, perhaps, identify early ventricular dysfunction during COVID-19 infection, all without exposing others and using additional resources. Depending on the capabilities of the machines used, images obtained by UAPE, POCUS, and critical care echocardiography practitioners can often be saved to allow remote interpretive assistance from more experienced echocardiographers. Archiving these images for review should help focus future imaging studies and provide comparisons of cardiac structure and function over time. In some cases, review of these images by a consulting cardiovascular specialist may obviate the need for echocardiography (and therefore reduce staff exposure), as pertinent clinical questions will be answered (e.g., etiology of hypotension). In other cases, they will indicate the need for more advanced imaging (e.g., wall motion and quantitative valvular assessment). Therefore, these images should be saved and archived whenever possible. Some devices use a camera that allows a sonographer or another imaging expert to remotely guide probe placement.

Along the same lines, echocardiographic studies performed on patients with suspected or confirmed COVID-19 should be as focused as necessary to obtain diagnostic views but should also be comprehensive enough to avoid the need to return for additional images. Each study should be tailored to the indication and planned in advance, after review of images from past examinations and other imaging modalities. Complete examinations may be necessary in some circumstances. Plans for ultrasound-enhancing agent (UEA) use should be made in advance to prevent a sonographer's having to wait for the agent to be delivered or having to use more PPE to exit the patient's room to obtain the agent. Although the safety of UEAs specifically in patients with COVID-19 has not yet been determined, they have been used and proved safe in patients in intensive care units. The use of UEAs may therefore be considered in such cases as long as the benefits in terms of diagnostic yield and scan time are favorable.

Regardless of the type of study (UAPE, POCUS, critical care echocardiography, or comprehensive echocardiography), prolonged scanning can expose these clinicians to added risk. An additional consideration when performing limited TTE is the limitations that may be posed by layers of protective equipment on image quality. Therefore, these studies should not be performed by a sonography student or any other novice or inexperienced practitioner, to minimize scanning time while obtaining images of the highest possible quality.

Finally, the results of the examination should be rapidly reviewed and key findings recorded immediately on the patient's record and communicated to the primary care team to allow hemodynamic management to be optimized.

The group therefore recommends the following:

-

•

Echocardiographic examinations should be planned ahead, on the basis of indications, clinical information, laboratory data, and other imaging findings, to allow a focused sequence of images that help with management decisions.

-

•

The use of UEAs should be considered before an examination to avoid the need to prolong scan time while awaiting preparation of the agent.

-

•

Scan times should be minimized by excluding students or novice practitioners from performing imaging.

-

•

The imaging team should ensure rapid review and reporting of key findings in the patient's record and communicating them with the primary care team.

Protection

Personnel

Imaging should be performed according to local standards for the prevention of virus spread. Meticulous and frequent hand washing is crucial. At some institutions, the level of PPE required may depend on the risk level of the patient with regard to COVID-19 (minimal risk when COVID-19 is not suspected, moderate risk when it is suspected, and high risk when it is confirmed). At some institutions, suspected and confirmed cases are treated similarly. The types of PPE can be divided into levels or categories (see Table 1 ):

-

•

Standard care involves hand washing or hand sanitization and use of gloves. The use of a surgical face mask in this setting may also be considered.

-

•

Droplet precautions include gown, gloves, head cover, face mask, and eye shield.

-

•

Airborne precautions add special masks (e.g., N-95 or N-99 respirator masks, powered air-purifying respirator systems) and shoe covers.

Table 1.

Precaution types and PPE

| Hand washing | Gloves/double gloves | Isolation gown | Surgical mask | N-95 or N-99 mask | Face shield | PAPR system | Surgical cap | Shoe cover | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Standard | X | X | X | ||||||

| Special droplet | X | X | X | X∗ | X∗ | X | X | X | X |

| Airborne† | X | X | X | X | X | X | X | X |

PAPR, Powered air -purifying respirator.

This is a general guide based on current practice and recommendations at the present time and is subject to change and modification to fit local procedures and practice patterns.

Surgical mask may be used for droplet precautions to conserve N-95 or N-99 respirators.

Patient location may determine level of protection (e.g., airborne precautions used for all patients in the intensive care unit setting).

The local application of each component of PPE can vary according to the level or type of risk for TTE and stress echocardiography, but airborne precautions are required during TEE for suspected and confirmed cases, because of the increased risk for aerosolization. Surgical face masks for patients are recommended for those who are symptomatic and undergoing surface echocardiographic examinations, provided institutional resources allow this strategy for source control.10

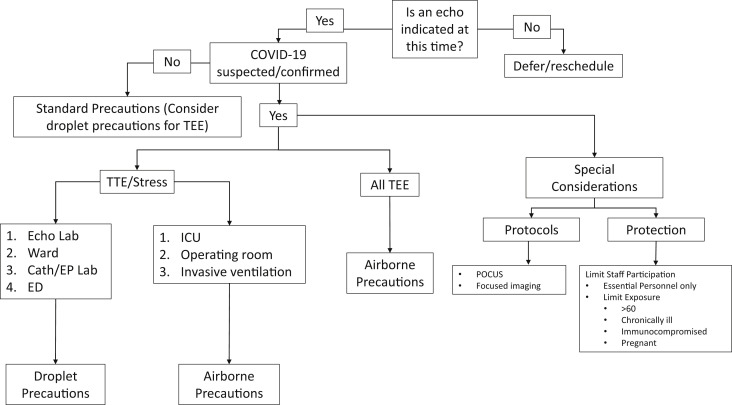

It is important to reiterate that the type of PPE to be used in specific cases will depend on local institutional policy and resources. The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention provides updated guidelines for PPE use for health care workers.4 The suggested approach to performing echocardiographic procedures and level of PPE is provided in Figure 1 .

Figure 1.

Suggested algorithm for determining indication and level of protection. ED, Emergency department; EP, electrophysiology; ICU, intensive care unit.

Equipment

Equipment care is critical in the prevention of transmission. Some institutions cover probes and machine consoles with disposable plastic and forgo the use of electrocardiographic stickers. It is important to note that the benefit of using protective covers must be balanced against the potential for suboptimal images and prolongation of scan time. Some institutions set aside certain machines or probes for use on patients with suspected or confirmed infection. Although SARS-CoV-2 is sensitive to most standard viricidal disinfectant solutions, care must be taken when cleaning. Local standards vary, but echocardiographic machines and probes should be thoroughly cleaned, ideally in the patient's room and again in the hallway. Smaller, laptop-sized portable machines are more easily cleaned, but use of these machines should be balanced against potential trade-offs in image quality and functionality. Please consult vendors' disinfecting guidelines, available on their websites, as procedures vary and could affect the functionality of machines. Transesophageal echocardiographic probes should undergo cleaning in the room (including the handle and cord) and then be transferred in a closed container to be immediately disinfected according to the manufacturer's recommendations. The exact steps to be followed for disinfection of the TEE probe and equipment will depend on local institutional protocols that usually are guided by infectious disease experts and resource availability. The American Institute for Ultrasound in Medicine has specific guidelines for disinfection of ultrasound equipment.11

Role of Learners

The performance and interpretation of echocardiographic studies, especially those in suspected or confirmed COVD-19 cases, should be limited to essential personnel. For TEE, practices may vary, but there should be at most one person to handle the probe and another to operate the machine controls, along with another to administer sedation. Medical education remains important, and echocardiographic practitioners play a crucial role in teaching essential components of cardiovascular medicine, as well as scanning and interpretation skills, to a wide variety of learners. Medical and sonography students, residents, fellows, and practicing physicians gain knowledge and experience through rotations on echocardiography services, through observing the performance of studies, hands-on scanning, and reading with experts. In the current environment, however, elective rotations should be suspended, and restrictions should be placed on trainees who are not essential to clinical care. At many institutions, advanced trainees (e.g., fellows) provide crucial off-hours scanning and interpretation but must follow all applicable procedures to reduce infection transmission. Training and education can be moved “online.” The ASE and others provide multiple educational offerings, including webinars and lectures. A variety of simulators are available to teach scanning skills without involving patients.

Other Considerations

In addition to limiting the number of echocardiography practitioners involved in scanning, consideration should be given to limiting the exposure of staff members who may be particularly susceptible to severe complications of COVID-19. Staff members who are >60 years of age, have chronic conditions, are immunocompromised, or are pregnant may wish to avoid contact with patients suspected or confirmed to have COVID-19, depending on local procedures.

The risk for transmission also is present in reading rooms. Keyboards, monitors, mice, chairs, phones, desktops, and doorknobs should be frequently cleaned and ventilation provided wherever possible. At some institutions, the echocardiography laboratory reading room is a place where many clinical services congregate to review images. In the current environment, it may be advisable to ask these services to review images remotely while speaking with the echocardiographer-consultant by phone, or review images together in a webinar.

Conclusion

The provision of echocardiographic services remains crucial in this difficult time of the SARS-CoV-2 outbreak. Working together, we can continue to provide high-quality care while minimizing risk to ourselves, our patients, and the public at large. Carefully considering whom to image, where to image, and how to image has the potential to reduce the risk for transmission. A summary of these recommendations is provided in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Summary recommendations.

Acknowledgments

This statement was prepared by James Kirkpatrick, MD, Carol Mitchell, Smadar Kort, MD, Judy Hung, MD, Cynthia Taub, MD, and Madhav Swaminathan, MD, and approved by the ASE executive committee on March 24, 2020. Protocols and procedures used in the preparation of this document courtesy of Madhav Swaminathan (Duke University, Durham, NC), Muhammad Saric (New York University Medical Langone Medical Center, New York), Mingxing Xie (Union Hospital, Tongji Medical College, Huazhong University of Science and Technology, Wuhan, China), Cynthia Taub (Montefiore Medical Center, Albert Einstein College of Medicine, Bronx, NY), Lissa Sugeng (Yale University, New Haven, CT), Smadar Kort (Stony Brook University, Stony Brook, NY), Judy Hung (Massachusetts General Hospital, Boston, MA), Marielle Scherer-Crosbie (University of Pennsylvania, Philadelphia, PA), Ray Stainback (Baylor St. Luke's Medical Center, Houston, TX), and James Kirkpatrick (University of Washington, Seattle, WA). Additional guidance was provided by the British Society of Echocardiography and Societa Italiana di Ecocardiograpfia e Cardiovascular Imaging.

Footnotes

Notice and Disclaimer: This statement reflects recommendations based on expert opinion, national guidelines, and available evidence. Our knowledge with regard to COVID-19 continues to evolve, as do our institutional protocols for dealing with invasive and noninvasive procedures and practice of personal protective equipment. Readers are urged to follow national guidelines and their institutional recommendations regarding best practices to protect their patients and themselves. These reports are made available by the American Society of Echocardiography (ASE) as a courtesy reference source for its members. The reports contain recommendations only and should not be used as the sole basis to make medical practice decisions or for disciplinary action against any employee. The statements and recommendations contained in these reports are primarily based on the opinions of experts, rather than on scientifically verified data. ASE makes no express or implied warranties regarding the completeness or accuracy of the information in these reports, including the warranty of merchantability or fitness for a particular purpose. In no event shall ASE be liable to you, your patients, or any other third parties for any decision made or action taken by you or such other parties in reliance on this information. Nor does your use of this information constitute the offering of medical advice by ASE or create any physician-patient relationship between ASE and your patients or anyone else.

Conflicts of interest: None.

References

- 1.World Health Organization WHO Director-General's opening remarks at the media briefing on COVID-19—11 March 2020. https://www.who.int/dg/speeches/detail/who-director-general-s-opening-remarks-at-the-media-briefing-on-covid-19---11-march-2020 Available at:

- 2.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R., Fan G., Liu Y., Liu Z. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Zheng Y.Y., Ma Y.T., Zhang J.Y., Xie X. COVID-19 and the cardiovascular system. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41569-020-0360-5. In press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Interim infection prevention and control recommendations for patients with suspected or confirmed coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in healthcare settings. 2020. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/infection-control/control-recommendations.html Available at:

- 5.Writing Group Members. Doherty J.U., Kort S., Mehran R., Schoenhagen P., Soman P., Dehmer G.J. ACC/AATS/AHA/ASE/ASNC/HRS/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR/STS 2019 appropriate use criteria for multimodality imaging in the assessment of cardiac structure and function in nonvalvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and the Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2019;32:553–579. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2019.01.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Writing Group for Echocardiography in Outpatient Pediatric Cardiology. Campbell R.M., Douglas P.S., Eidem B.W., Lai W.W., Lopez L., Sachdeva R. ACC/AAP/AHA/ASE/HRS/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR/SOPE 2014 appropriate use criteria for initial transthoracic echocardiography in outpatient pediatric cardiology: a report of the American College of Cardiology Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and Society of Pediatric Echocardiography. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2014;27:1247–1266. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2014.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Doherty J.U., Kort S., Mehran R., Schoenhagen P., Soman P., Dehmer G.J. ACC/AATS/AHA/ASE/ASNC/HRS/SCAI/SCCT/SCMR/STS 2017 appropriate use criteria for multimodality imaging in valvular heart disease: a report of the American College of Cardiology Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Association for Thoracic Surgery, American Heart Association, American Society of Echocardiography, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance, and Society of Thoracic Surgeons. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2018;31:381–404. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2017.08.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force. American Society of Echocardiography. American Heart Association. American Society of Nuclear Cardiology. Heart Failure Society of America. Heart Rhythm Society ACCF/ASE/AHA/ASNC/HFSA/HRS/SCAI/SCCM/SCCT/SCMR 2011 appropriate use criteria for echocardiography. A report of the American College of Cardiology Foundation Appropriate Use Criteria Task Force, American Society of Echocardiography, American Heart Association, American Society of Nuclear Cardiology, Heart Failure Society of America, Heart Rhythm Society, Society for Cardiovascular Angiography and Interventions, Society of Critical Care Medicine, Society of Cardiovascular Computed Tomography, Society for Cardiovascular Magnetic Resonance American College of Chest Physicians. J Am Soc Echocardiogr. 2011;24:229–267. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2010.12.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Guglielmo M., Baggiano A., Muscogiuri G., Fusini L., Andreini D., Mushtaq S. Multimodality imaging of left atrium in patients with atrial fibrillation. J Cardiovasc Comput Tomogr. 2019;13:340–346. doi: 10.1016/j.jcct.2019.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Strategies for optimizing the supply of facemasks. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/ppe-strategy/face-masks.html Available at:

- 11.American Institute for Ultrasound in Medicine Guidelines for cleaning and preparing external- and internal-use ultrasound transducers between patients & safe handling and use of ultrasound coupling gel. https://www.aium.org/officialStatements/57 Available at: [DOI] [PubMed]

Resources

- 1.ASE COVID-19 resource page. https://www.asecho.org/covid-19-resources/

- 2.Connect@ASE COVID-19 discussion page. https://connect.asecho.org/groups/534-Coronavirus-(COVID-19)

- 3.American Institute for Ultrasound in Medicine guidelines for equipment disinfection. https://www.aium.org/officialStatements/57

- 4.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention COVID-19 resource page. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention recommendations for infection prevention and control. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/hcp/infection-control-recommendations.html

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention visual guide for using personal protective equipment. https://www.cdc.gov/hai/pdfs/ppe/PPE-Sequence.pdf