To the Editor,

The coronavirus is an enveloped, positive-sense, single-stranded RNA virus. It could be classified into four major genera: Alphacoronavirus, Betacoronavirus, Gammacoronavirus and Deltacoronavirus, based on serological and genetic studies (Li, 2016). The Alphacoronavirus and Betacoronavirus mainly infect mammals, whereas the Gammacoronavirus and Deltacoronavirus mainly infect avians (Tang et al., 2015). The coronavirus poses a serious threat to human health and global security because several coronaviruses could cross-species to infect humans, such as the Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (SARS-CoV) and Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) (Lu et al., 2015; Peck et al., 2015; Smith, 2006). The SARS-CoV was reported to cause 774 human deaths in 37 countries from 2002 to 2003 (Smith, 2006), while the MERS-CoV is still persistently infecting humans in many countries and has already caused more than 700 deaths around the world (World Health Organization, 2017). How to prevent and control the coronavirus has become a global concern.

The genome of the coronavirus generally encodes more than ten proteins (Peck et al., 2015; Yang et al., 2013). Among them, the spike surface envelope glycoprotein is responsible for binding to host receptors and determines the tissue tropism and host range of the virus to a large extent (Li, 2015, Li, 2016; Lu et al., 2015). The spike protein contains an ectodomain, a transmembrane anchor and a short intracellular tail. Among them, the ecotodomain could be cleaved into a receptor-binding S1 subunit and a membrane-fusion S2 subunit during molecular maturation. The S1 subunit binds to a host receptor for entry into the host cell (Li, 2015, Li, 2016; Qian et al., 2015). Depending on the coronavirus species, the spike protein could bind to either protein receptors or glycans (Li, 2016). Multiple receptors were reported for the coronavirus. This is largely attributed to the double receptor-binding domains (RBD) on the S1 subunit: one RBD is located in the N-terminal (denoted as NTD), while the other is located in the C-terminal (denoted as CTD) (Li, 2016). One coronavirus species generally uses one RBD. Some coronaviruses used NTD, for example, the mouse hepatitis virus (MHV) (Peng et al., 2011), while the others used CTD, such as SARS-CoV (Lu et al., 2015) and MERS-CoV (Lu et al., 2015). Previous studies suggest that the usage of two RBDs could facilitate expansion of host range of the virus (Li, 2015, Li, 2016). However, the mechanism under the RBD usage is still obscure. Besides, RBD usage of most coronavirus species is still unknown. Here, we attempted to develop a computational method for determining RBD usage of the coronavirus based on the protein sequence of S1.

We firstly manually compiled twelve coronavirus species with RBD usage reported from the literature (Table S1). Four coronavirus species used NTD, including the bovine coronavirus (BCoV), MHV, IBV and the human coronavirus OC43 (HCoV-OC43), while the other eight coronavirus species used CTD, including the human coronavirus 229E (HCoV-229E), feline coronavirus (FCoV), bat coronavirus HKU4 (BatCoV-HKU4), human coronavirus HKU1 (HCoV-HKU1), human coronavirus NL63 (HCoV-NL63), MERS-CoV, SARS-CoV and transmissible gastroenteritis virus (TGEV). The protein sequences of the spike protein S1 subunit of these viruses were collected from the NCBI protein database. For convenience, only 800 amino acids in the N-terminal of each spike protein sequence, which covered the S1 subunit of all coronavirus species, were kept for further analysis (Supplementary Methods).

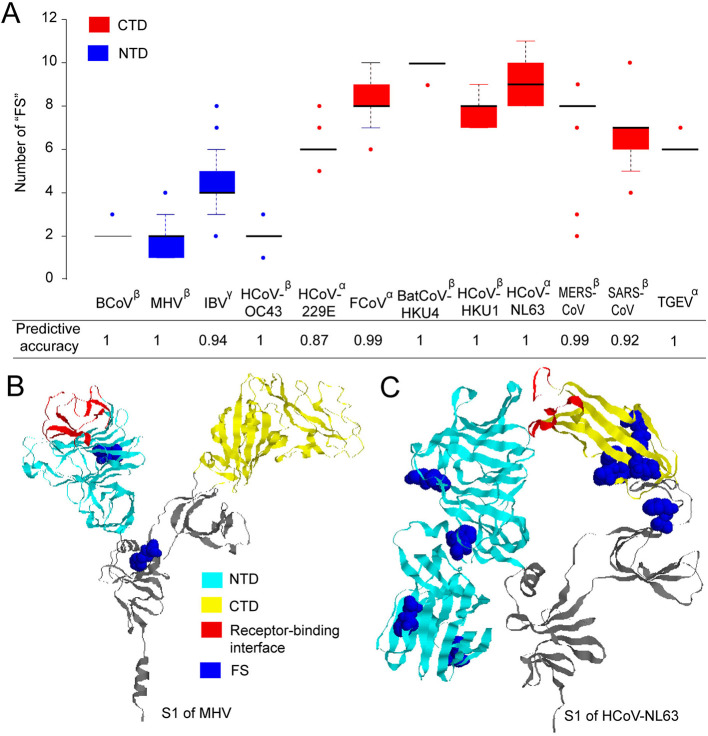

Then, the frequency of kmers (one or two amino acids) was used individually to predict whether a coronavirus used NTD or CTD for binding to the receptor (see Supplementary Methods and Table S2). Most of them achieved a predictive accuracy ranging from 0.6 to 0.8. Surprisingly, we found a pair of amino acids, i.e., “FS”, could discriminate the RBD usage of these 12 coronavirus species with an average predictive accuracy of 97% (Fig. 1A). More specifically, it achieved an accuracy of 100% for BCoV, MHV, HCoV-OC43, BatCoV-HKU4, HCoV-HKU1, HCoV-NL63 and TGEV, and an accuracy of 0.94, 0.87, 0.99, 0.99 and 0.92 for IBV, HCoV-229E, FCoV, MERS-CoV and SARS-CoV, respectively. Analyzing the number of “FS” in the protein sequence of S1 subunit of these viruses, we found that the viruses using NTD generally had less than 3 “FS”s in S1 expect for IBV, while the viruses using CTD generally had 6 or more “FS”s in S1 (Fig. 1A).

Fig. 1.

Predicting the RBD usage of the coronavirus based on the number of “FS” in the protein sequence of the spike protein S1 subunit. (A) The distribution of the number of “FS” in S1 and the predictive accuracy based on the number of “FS” in 12 coronavirus species. The coronavirus species using NTD and CTD were colored in blue and red, respectively. The genus each virus belongs to was labeled in the top right of the virus name. (B) and (C) refer to the 3D structure of S1 subunit for MHV and HCoV-NL63, respectively. The receptor-binding interface was inferred manually from the spike-receptor complex (PDB id: 3r4d for MHV and 3kbh for HCoV-NL63). NTD and CTD were colored in cyan and yellow respectively. The “FS”s were colored in blue. (For interpretation of the references to colour in this figure legend, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.)

Further analysis of the ratio between the observed and expected number of “FS” in S1 protein of these viruses showed that the “FS” was under-represented in the viruses using NTD (Fig. S1), i.e., the observed number of “FS” in S1 was lower than that of the expected; while for the viruses using CTD, the “FS” was generally over-represented in S1. We next analyzed the location of “FS”s on the 3D structure of S1 protein of the coronavirus. Fig. 1B & C show the 3D structures for S1 protein of MHV and HCoV-NL63 respectively. For most coronavirus species, the “FS”s (colored in blue) were generally scattered around the S1 protein (Fig. 1B & C and Fig. S2). Few of them were located in or near the receptor-binding interface (colored in red), suggesting that “FS” may not contribute directly to the virus-receptor interaction. One exception is the SARS-CoV, for which there was one “FS” in the interface (Fig. S2A). More efforts are needed to clarify how the “FS” influences the RBD usage of the coronavirus.

Finally, except for 12 coronavirus species mentioned above, we inferred the RBD usage of all other coronavirus species which had S1 protein sequence available in the NCBI protein database (Table S3), based on the number of “FS” in S1 protein. A total of 31 coronavirus species covering all four major genera were used in prediction. For the virus in Alphacoronavirus, except for the Mink coronavirus 1, all the other coronavirus species were predicted to use CTD; while for other genera, most coronavirus species were predicted to use NTD.

Overall, this work provides a simple and effective method for inferring the RBD usage of the coronavirus based on the protein sequence of the spike protein. It may not only help understand the mechanisms behind the RBD usage of the coronavirus, but also help for identification of host receptors for the virus.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the National Key Plan for Scientific Research and Development of China (2016YFD0500300 and 2016YFC1200200), the National Natural Science Foundation of China (31500126 and 31671371) and the Chinese Academy of Medical Sciences (2016-I2M-1-005).

The authors have declared that no competing interests exist.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.meegid.2018.03.028.

Contributor Information

Wenjie Tan, Email: tanwj28@163.com.

Yousong Peng, Email: pys2013@hnu.edu.cn.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary material

References

- Li F. Receptor recognition mechanisms of coronaviruses: a decade of structural studies. J. Virol. 2015;89:1954–1964. doi: 10.1128/JVI.02615-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li F. Structure, function, and evolution of coronavirus spike proteins. Ann. Rev. Virol. 2016;3:237–261. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-110615-042301. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lu G.W., Wang Q.H., Gao G.F. Bat-to-human: spike features determining 'host jump' of coronaviruses SARS-CoV, MERS-CoV, and beyond. Trends Microbiol. 2015;23:468–478. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2015.06.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peck K.M., Burch C.L., Heise M.T., Baric R.S. Coronavirus host range expansion and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus emergence: biochemical mechanisms and evolutionary perspectives. Ann. Rev. Virol. 2015;2(2):95–117. doi: 10.1146/annurev-virology-100114-055029. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peng G.Q., Sun D.W., Rajashankar K.R., Qian Z.H., Holmes K.V., Li F. Crystal structure of mouse coronavirus receptor-binding domain complexed with its murine receptor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 2011;108:10696–10701. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1104306108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Qian Z.H., Ou X.Y., Goes L.G.B., Osborne C., Castano A., Holmes K.V., Dominguez S.R. Identification of the receptor-binding domain of the spike glycoprotein of human betacoronavirus HKU1. J. Virol. 2015;89:8816–8827. doi: 10.1128/JVI.03737-14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith R.D. Responding to global infectious disease outbreaks: lessons from SARS on the role of risk perception, communication and management. Soc. Sci. Med. 2006;63:3113–3123. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2006.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tang Q., Song Y.L., Shi M.J., Cheng Y.Y., Zhang W.T., Xia X.Q. Inferring the hosts of coronavirus using dual statistical models based on nucleotide composition. Sci. Rep. 2015;5 doi: 10.1038/srep17155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) 2017. http://www.who.int/emergencies/mers-cov/en/ Available at.

- Yang Y., Zhang L., Geng H.Y., Deng Y., Huang B.Y., Guo Y., Zhao Z.D., Tan W.J. The structural and accessory proteins M, ORF 4a, ORF 4b, and ORF 5 of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) are potent interferon antagonists. Protein Cell. 2013;4:951–961. doi: 10.1007/s13238-013-3096-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary material