Abstract

The novel coronavirus (SARS-CoV-2) infection which has been known as Coronavirus diseases 2019 COVID-19 has become an endemic emergent situation by the World Health Organization. So far, no successful specific treatment has been found for this disease. As has been reported, most of non-survivor patients with COVID-19 (70%) had septic shock which was significantly higher than survived ones. Although the exact pathophysiology of septic shock in these patients is still unclear, it seems to be possible that part of it would be due to the administration of empiric antibiotics with inflammatory properties especially in the absence of bacterial infection. Herein, we have reviewed possible molecular pathways of septic shock in the patients who have received antibiotics with inflammatory properties which mainly is release of interleukin 1β (IL-1β), IL-6, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF- α) through different routes. Altogether, we highly recommend clinicians to look after those antibiotics with anti-inflammatory activity for both empiric antibiotic therapy and reducing the inflammation to prevent septic shock in patients with diagnosed COVID-19.

Key Words: Coronavirus diseases 2019, SARS-CoV-2, Septic shock, Antibiotics, Inflammation

In December 2019, a novel coronavirus infection was isolated in Wuhan, Hubei Province of China which led to an outbreak of a disease further called coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). According to the evaluations, the pathogen causes severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2). The clinical feature mostly includes pneumonia accompanied with other complications such as acute respiratory distress syndrome and septic shock (1).

A retrospective, multicenter cohort study evaluated survived (discharged) and non-survived (died) COVID-19 patients. It was shown that the non-survived group had statistically significant prevalence of sepsis (100% [n = 54] vs. 42% [n = 58], p <0.0001) and septic shock (70% [n = 38] vs. 0%, p <0.0001) compared to the survived group (1). From a pathophysiological approach, the key regulator of sepsis and especially septic shock is the activation of nuclear factor-kappa B (NF-κB) which in turn triggers the over-expression of different pro-inflammatory cytokines such as interleukin 1β (IL-1β), IL-6, IL-8, and tumor necrosis factor α (TNF-α) (2).

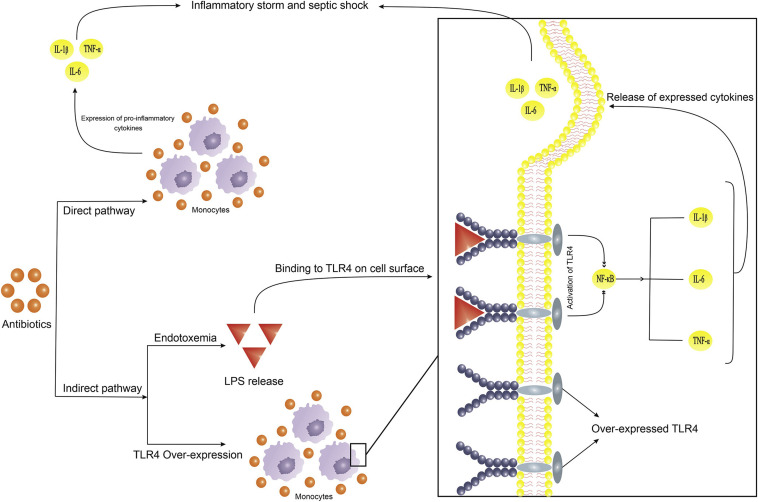

Previously, we have highlighted that the consumption of some antibiotics in the lack of bacterial infection could lead to an inflammatory storm through direct and indirect pathways. In the direct pathway, the antibiotic itself can stimulate the immune cells to secret pro-inflammatory cytokines such as IL-1β, IL-6, and TNF-α (Figure 1 ) (3). As an example, it has been shown that a single dose of ceftazidime induced the expression of IL-6 and TNF-α in the absence of any infection (4). Aside from pro-inflammatory cytokines, some antibiotics could also increase the expression of different Toll-like receptors (TLRs) especially TLR4 (3). In the indirect pathway, studies have shown that treatment with antibiotics in the absence of bacterial infection could cause an increase in gut endotoxins (neomycin sulfate and streptomycin) (5) or even result in endotoxemia (tobramycin plus polymyxin and ciprofloxacin) (3). According to Figure 1, overexpressed TLR4, as well as lipopolysaccharide release (endotoxemia), could lead to overexpression of pro-inflammatory cytokines through activation of NF-κB (2).

Figure 1.

Antibiotics affect pro-inflammatory and pattern recognition molecules (PRPs) expression which may cause an inflammatory storm. (TLR4: Toll-like receptor 4; IL: Interleukin; TNF-α: Tumor necrosis factor α; NF-κB: Nuclear factor-κ (B).

During the treatment course of patients diagnosed with COVID-19, antibiotic therapy is one of the backbone treatments as up to 95% of patients have received them. According to the data, there is not enough evidence for the virus-induced sepsis and septic shock in patients with COVID-19 (1). Regarding the mentioned effects of antibiotic administration in the non-bacterial infectious situations, authors suggest that the administration of antibiotics in these patients should be proceeded very carefully to prevent any antibiotic-induced inflammatory storm. Also, clinicians may look after those antibiotics with anti-inflammatory activity for both empiric antibiotic therapy and reducing the inflammation to reduce septic shock.

Competing Interests

All the authors declare no actual or potential conflict of interest related to this study.

Funding

None.

Supplementary data

References

- 1.Zhou F., Yu T., Du R. Clinical course and risk factors for mortality of adult inpatients with COVID-19 in Wuhan, China: a retrospective cohort study. Lancet. 2020;395:1054–1062. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30566-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Cecconi M., Evans L., Levy M. Sepsis and septic shock. Lancet. 2018;392:75–87. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)30696-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hantoushzadeh S., Anvari Aliabad R., Norooznezhad A.H. Antibiotics, Pregnancy, and Fetal Mental Illnesses: Where is the link? Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2020.01.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Alkharfy K.M., Kellum J.A., Frye R.F. Effect of ceftazidime on systemic cytokine concentrations in rats. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2000;44:3217–3219. doi: 10.1128/aac.44.11.3217-3219.2000. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rogers M., Moore R., Cohen J. The relationship between faecal endotoxin and faecal microflora of the C57BL mouse. Epidemiol Infect. 1985;95:397–402. doi: 10.1017/s0022172400062823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.