Abstract

Acute respiratory failure with diffuse pulmonary opacities is an unusual manifestation following influenza vaccination. We report herein a patient with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease who developed fever with worsening of respiratory symptoms and severe hypoxemia requiring ventilatory support shortly after influenza vaccination. Bronchoalveolar lavage was compatible with acute eosinophilic pneumonia. Rapid clinical improvement was observed 2 weeks after systemic corticosteroid treatment, followed by radiographic improvement at 4 weeks. No disease recurrence was observed at the 6-month follow-up.

Keywords: Influenza vaccination, Acute respiratory failure, Diffuse lung disease, Eosinophilic pneumonia

1. Introduction

Influenza vaccination is recommended in the care of patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease (COPD), because it clearly reduces acute influenza respiratory illness, late exacerbation of COPD occurring 3–4 weeks after vaccination, and severe exacerbation requiring mechanical ventilation.1 Although there is a significant increase in the occurrence of local adverse reactions following vaccination, a life-threatening condition with severe respiratory distress and diffuse pulmonary opacities rarely occurs. Only seven cases of influenza vaccine-induced interstitial lung disease (ILD) have been reported.2 We report herein the case of an elderly patient with severe COPD who developed fever with worsening of respiratory symptoms and severe hypoxemia requiring ventilatory support shortly after influenza vaccination. The diagnosis of acute eosinophilic pneumonia was made by bronchoscopy and bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL). The clinical symptoms and radiographic abnormalities improved following systemic corticosteroid treatment.

2. Case report

An 86-year-old Thai man with severe COPD presented with increasing breathlessness and fever for 3 days. He also had generalized malaise, myalgia, and a cough with scant sputum. On physical examination, his temperature was 38.7 °C, respiratory rate 26/min, heart rate 90 beats/min, and blood pressure 130/80 mmHg. His oxygen saturation on room air was 95%. Lung auscultation revealed coarse crackles and wheezes in the bilateral lower lungs. Three months prior, he had experienced an acute COPD exacerbation that had required routine COPD medications (inhaled salmeterol/fluticasone and ipratropium bromide) and 5 days of azithromycin and prednisolone. His respiratory symptoms had gradually improved and returned to near baseline over the next 6 weeks. Other medical conditions included atrial fibrillation and hypertension treated with aspirin and valsartan.

Seven days prior to this presentation, in March 2012, he received intramuscular injection of inactivated influenza vaccine (Vaxigrip, Sanofi Pasteur) containing of A/California/7/2009 (H1N1) pdm09-like virus, A/Perth/16/2009 (H3N2)-like virus, and B/Brisbane/60/2008-like virus in his arm. He denied a history of allergic reaction to any medications or eggs, and exposure to dust, indoor and outdoor smoke, or fumes and influenza vaccine.

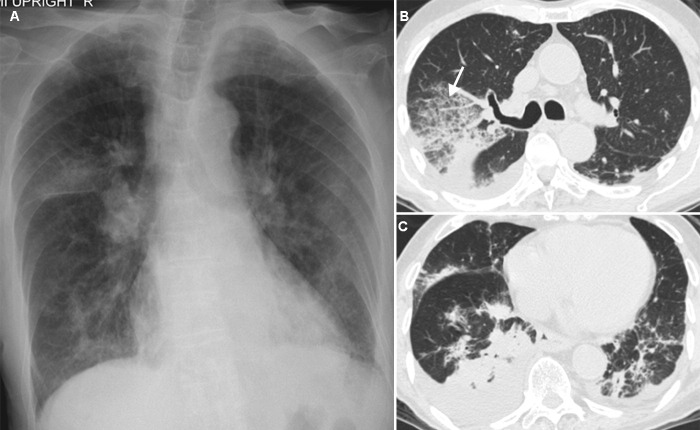

Initial laboratory tests revealed a white blood cell (WBC) count of 15.52 × 109/l (neutrophils 84%, lymphocytes 9%, monocytes 6%, and eosinophils 1%). Blood chemistry was normal except for albumin of 19 g/l (normal 34–50 g/l). The initial chest radiograph revealed multiple patchy and/or peribronchial opacities in both lungs, notably in the right upper lobe (Figure 1A). Sputum collection was inadequate for microbiological analysis. Testing of a nasopharyngeal swab for influenza and other common respiratory viruses by multiplex PCR was negative. Intravenous ceftriaxone and oral azithromycin were given.

Figure 1.

(A) Initial chest radiograph obtained 6 days after the influenza vaccine was administered, showing multi-focal areas of patchy and peribronchial opacities in both lungs. (B) Chest CT obtained 9 days after the influenza vaccine was administered, revealing a large area of ground-glass opacities with superimposed interlobular septal thickening, the so-called crazy-paving appearance (arrow), in the right upper lobe. (C) Chest CT at the level of the lower lungs, showing multi-focal areas of airspace consolidation in both lungs, with small amounts of bilateral pleural effusion.

Following this treatment, he continued to have daily fever without clinical improvement, and became more hypoxemic 4 days later. Room air arterial blood gases revealed pH 7.43, pCO2 34.3 mmHg, and pO2 48 mmHg. He subsequently required non-invasive ventilation and eventually mechanical ventilation. A computed tomography (CT) scan of the chest (Figure 1, B and C) revealed multi-focal areas of airspace consolidation involving the bilateral lower lobes and the right middle lobe, with a large area of ground-glass opacity with superimposed interlobular septal thickening in the right upper lobe. He underwent bronchoscopy with BAL and a transbronchial lung biopsy via the right upper lobe on day 12 of hospitalization. Analysis of the BAL fluid revealed a WBC count of 445 × 106/l (neutrophils, 50%, macrophages, 29%, lymphocytes, 6%, and eosinophils, 15%). Gram stain, acid-fast bacillus (AFB) stain, PCR testing for tuberculosis (TB), multiplex PCR for common respiratory viruses such as adenovirus, coronavirus, respiratory syncytial virus, etc., fungal stain, and bacterial culture of the BAL fluid were all negative. A repeated blood count showed a WBC count of 10.2 × 109/l (neutrophils 73%, lymphocytes 9%, monocytes 9%, and eosinophils 9%). Fresh smears for parasites, for example, Strongyloides larvae and Ascaris, were negative. The transbronchial lung biopsy specimen showed no evidence of granuloma or malignancy.

All antimicrobials were discontinued, and intravenous dexamethasone 5 mg was administered every 12 h. The patient's fever subsided and the dyspnoea was markedly improved 48 h after the treatment. Oral prednisolone 60 mg daily was then given instead. A follow-up chest CT obtained 4 weeks later revealed substantial improvement. Oral prednisolone was gradually tapered over the next 2 weeks. Cultures for TB and fungus from BAL fluid were negative. He returned to his baseline respiratory condition with complete resolution of the radiographic abnormalities. No recurrence was observed at the 6-month follow-up.

The numbers of interferon gamma (IFN-γ)- and interleukin 5 (IL-5)-releasing cells in the peripheral blood were measured by ELISPOT assay (Mabtech, Sweden) upon stimulation with influenza vaccine. A strong IFN-γ response was demonstrated in two healthy age-matched adults (352 and 478 spots-forming cells (SFC)/106 peripheral blood mononuclear cells (PBMC), respectively) in whom the same strain of inactivated influenza vaccine was given during the same period; in contrast, the magnitude of the IFN-γ response was much lower in this patient (14 SFC/106 PBMC). The numbers of IL-5-secreting cells were barely detectable in the patient (2 SFC/106 PBMC), but not found at all in the two control individuals.

3. Discussion

Influenza vaccination is currently recommended for every patient with COPD. Despite its benefits, serious adverse events following vaccination can occur, including neurological complications (Guillain–Barré syndrome, transverse myelitis) and anaphylaxis. Nevertheless, acute respiratory distress with diffuse pulmonary opacities, as in the present case, is rare.

To date, only seven cases of influenza vaccine-induced ILD following pandemic influenza A (H1N1) and seasonal influenza vaccines in 2009 and 2011 have been reported.2 The onset of respiratory symptoms ranged from 1 to 10 days after vaccination. The ages of patients ranged from 38 to 75 years. Fever and dyspnoea were the most common complaints. Four of the seven patients had pre-existing lung diseases, including idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis, lung cancer, post-lobectomy pneumothorax, and extrinsic allergic alveolitis. One case had no underlying disease. Six of the seven cases improved after systemic corticosteroid administration.

In previous reports, there was an increase in lymphocyte count in BAL fluid and a lymphocytic infiltrate in the lung biopsy specimens, with positive reaction to influenza vaccine by drug-induced lymphocyte stimulation test.2 This is different from our case, in whom eosinophils were higher than lymphocytes in the BAL fluid. Although the criteria for the diagnosis of eosinophilic pneumonia of acute (≤7 days) or subacute (≤1 month) duration requires a BAL eosinophil count of ≥25%, only severe cases have met this diagnostic criterion.3 Prior corticosteroid treatment in the present case might have affected the eosinophil count. The blood eosinophil count is rarely initially ≥300/μl, but will increase over time, as in the present case.

A lung biopsy is generally not required. After possible causes of eosinophilic pneumonia, including parasitic infestation, drug-induced eosinophilia, and dust or toxic substance exposure were excluded, recent exposure to the influenza vaccine was a plausible association.

Although the immunopathogenesis of eosinophilic pneumonia is currently unknown, there is evidence of a Th-2 cytokine-predominant (IL-5, IL-10, and IL-13) and low Th-1 cytokine (IL-2 and IFN-γ) response in this syndrome.4 We speculate that an aberration of the Th-1/Th-2 axis towards Th-2 against the influenza vaccine, confirmed by a very low frequency of influenza-specific IFN-γ releasing cells but comparable IL-5 releasing cells in this patient, might be responsible, at least in part, for the development of eosinophilic pneumonia. Additionally, the compensation of other pro-inflammatory cytokines such as tumour necrosis factor (TNF) and IL-1α/β could exert cytokine storm effects due to a defective influenza-specific IFN-γ response in this patient, contributing to the acute lung injury and systemic inflammatory responses. It has previously been demonstrated in cytokine receptor gene knockout mice that an up-regulation of other cytokines upon viral infection could be responsible for the cytokine storm that potentially occurred in these mice.5 Such hyperinflammatory responses possibly manifest as an endothelial dysfunction with increased pulmonary capillary permeability and as a sepsis syndrome.

In conclusion, influenza vaccination may cause a serious adverse effect in patients with pre-existing chronic respiratory diseases. Rapid respiratory deterioration with diffuse pulmonary opacities after vaccination should raise concerns regarding influenza vaccine-induced ILD, including acute eosinophilic pneumonia. Prompt diagnosis and treatment can alleviate this potentially fatal complication.

Conflict of interest: None to declare.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank Amnuay Thithapandha for his constructive suggestions and editing, and Pitsanu Detakarat, MS, for his help in preparing the images presented in this article.

Corresponding Editor: Eskild Petersen, Aarhus, Denmark

References

- 1.Poole PJ, Chacko E, Wood-Baker RW, Cates CJ. Influenza vaccine for patients with chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2006;CD002733. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 2.Watanabe S., Waseda Y., Takato H., Inuzuka K., Katayama N., Kasahara K. Influenza vaccine-induced interstitial lung disease. Eur Respir J. 2013;41:474–477. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00146912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Marchand E., Reynaud-Gaubert M., Lauque D., Durieu J., Tonnel A.B., Cordier J.F. Idiopathic chronic eosinophilic pneumonia. A clinical and follow-up study of 62 cases. Medicine (Baltimore) 1998;77:299–312. doi: 10.1097/00005792-199809000-00001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Katoh S., Matsumoto N., Matsumoto K., Fukushima K., Matsukura S. Elevated interleukin-18 levels in bronchoalveolar lavage fluid of patients with eosinophilic pneumonia. Allergy. 2004;59:850–856. doi: 10.1111/j.1398-9995.2004.00492.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Tisoncik J.R., Korth M.J., Simmons C.P., Farrar J., Martin T.R., Katze M.G. Into the eye of the cytokine storm. Microbiol Mol Biol Rev. 2012;76:16–32. doi: 10.1128/MMBR.05015-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]