Ebola virus disease was first discovered in 1976 in Zaire1 as a new lethal zoonotic disease affecting human beings. For 38 years, Ebola was restricted to localised outbreaks in a few remote regions of central Africa where it was brought under control rapidly, without attracting global attention.2 The first cases of the ongoing Ebola epidemic—which is the largest outbreak so far—occurred in December, 2013, in Guinea, west Africa.3 Complacency and inaction by national governments and international organisations, even after calls for support from non-governmental organisations such as Medécins sans Frontières, combined with poor health-care systems and infrastructures, led to a rapid increase in the number of cases of the disease, which spread rapidly into neighbouring Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Nigeria. It was only on Aug 8, 2014, that Ebola virus disease was declared a Public Health Emergency of International Concern by WHO.4 As of Jan 7, 2015, 20 747 clinically compatible cases of Ebola virus disease have been reported from nine countries: Guinea (2775), Liberia (8157), Sierra Leone (9780), Mali (8), Nigeria (20), Senegal (1), Spain (1), the USA (4), and the UK (1), with at least 8235 deaths (39·7% mortality rate).5

The current Ebola outbreak in west Africa is a grim reminder that novel zoonotic viruses that cause lethal human diseases remain a persistent threat to global health security. Without any obvious explanation, viruses can cross species to infect human beings. If they become easily transmissible among people, they can have a devastating effect regionally a long time after they were first discovered. Therefore, alertness and vigilance, within both health systems and global public health bodies, is needed. The intense political and media attention on Ebola for the past 5 months has overshadowed attention on other threats of ongoing global infectious diseases.

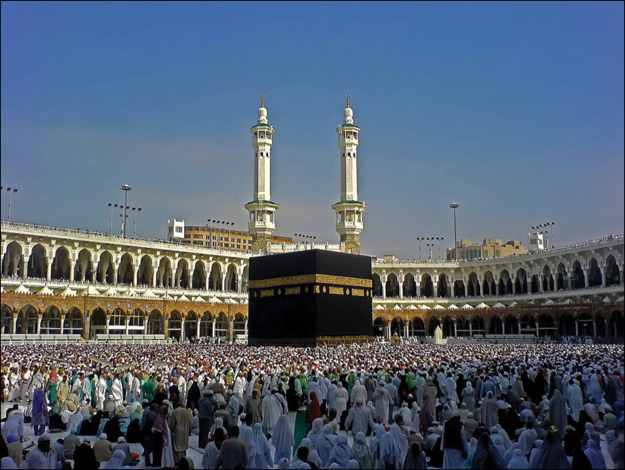

As with Ebola virus, the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) is a newly recognised viral zoonosis of human beings with a high mortality rate. MERS-CoV was first isolated from a patient who died from a severe respiratory illness in June, 2012, in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia.6 As of Jan 5, 2015, 944 laboratory-confirmed cases of MERS have been recorded, with a 37% mortality rate.7 Although most cases of MERS have occurred in Saudi Arabia and the United Arab Emirates, cases have also been reported from Europe, the USA, north Africa, and Asia in people with a history of travel to the Middle East. Since the virus was first identified in September 2012, seven MERS-related meetings of the WHO Emergency Committee have been convened.8 The small number of cases and low risk of human-to-human transmission have not yet warranted the declaration of MERS-CoV as a Public Health Emergency of International Concern.9 Large increases in the numbers of MERS cases in Saudi Arabia in April–May, 2013, in Al-Hasa province,10 and in Jeddah hospitals in April–May, 2014,11 were related to nosocomial outbreaks, poor hospital infection control measures, and improved screening. By contrast with Ebola virus disease, only a small amount of human-to-human transmission has been reported.9, 10, 11 Reassuringly, no cases of MERS occurred during the Hajj pilgrimage in October, 2014, but a recent increased number of cases has been reported in Taif province, Saudi Arabia.12

MERS-CoV evoked worldwide consternation and became a focus of the media spotlight, which continued for 2 years until it was overshadowed by the Ebola outbreak. Worryingly, 26 months since the first case of MERS-CoV was reported, many basic questions remain unanswered and it remains a serious threat to global health security.13 Little is known about its transmission characteristics. Although phylogenetic analysis of MERS-CoV isolates from human beings show that camels and bats are reservoirs for the virus, the exact mode of transmission to human beings is not yet known. Like all coronaviruses, MERS-CoV is prone to mutation and recombination and could acquire the ability to become more easily transmissible among human beings. If this occurred, it would increase the likelihood of a pandemic, which could potentially be exacerbated by the presence of millions of pilgrims from all continents, including Africa, who visit Saudi Arabia each year.14 As is the case with Ebola virus disease, no specific drug treatment or vaccine exists for MERS-CoV, and infection prevention and control measures are crucial to prevent spread of the disease.

© 2015 © Fazli Sameer/Demotix/Corbis

The persistence of MERS-CoV and Ebola virus disease draw attention to a global failure by public health systems to adequately assess and respond to such outbreaks, because of an absence of proper risk assessment and communication, transparency, and serious intent to define and control the outbreaks. In light of the shortcomings in existing public health surveillance capacity and infrastructures, a revised long-term strategy that addresses global governance of public health is needed. Recent statements from the G20 Summit in Brisbane, Australia, and from the World Bank Group suggest that world leaders are learning the lesson of the consequences of failure to invest in prevention, detection, and initiation of rapid aggressive early responses. Experiences from Ebola virus disease and MERS-CoV outbreaks show that all governments and WHO urgently need to implement a well-financed and well-managed response system in a sustainable way, well before the next infectious disease crisis emerges. In addition to the existing appropriate global priority focus on the Ebola virus disease, we need to ensure that MERS-CoV is not forgotten. Proactive surveillance, research into the epidemiology and pathogenesis, and development of new drugs and vaccines for all emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases that potentially threaten global health security15 should be maintained. There is no room for complacency.

Acknowledgments

We declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.WHO Ebola haemorrhagic fever in Zaire, 1976. Bull World Health Organ. 1978;56:271–293. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Feldmann H, Geisbert TW. Ebola haemorrhagic fever. Lancet. 2011;377:849–862. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(10)60667-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Baize S, Pannetier D, Oestereich L. Emergence of Zaire Ebola virus disease in Guinea. N Engl J Med. 2014;371:1418–1425. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1404505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.WHO Statement on the 1st meeting of the IHR Emergency Committee on the 2014 Ebola outbreak in West Africa. Aug 8, 2014. http://www.who.int/mediacentre/news/statements/2014/ebola-20140808/en/ (accessed Nov 30, 2014).

- 5.World Health Organization Global Alert and response Ebola response roadmap situation report. http://www.who.int/csr/disease/ebola/situation-reports/en/ (accessed Jan 8, 2015).

- 6.Zaki AM, van Boheemen S, Bestebroer TM. Isolation of a novel coronavirus from a man with pneumonia in Saudi Arabia. N Engl J Med. 2012;367:1814–1820. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1211721. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.World Health Organization Global Alert and response Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV)—Saudi Arabia. http://www.who.int/csr/don/05-january-2015-mers/en/ (accessed Jan 8, 2015).

- 8.WHO IHR Emergency Committee concerning Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. http://www.who.int/ihr/ihr_ec_2013/en/ (accessed Nov 12, 2014). [PubMed]

- 9.Zumla AI, Memish ZA. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus: epidemic potential or a storm in a teacup? Eur Respir J. 2014;43:1243–1248. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00227213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Assiri A, McGeer A, Perl TM. Hospital outbreak of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:407–416. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1306742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drosten C, Muth D, Corman VM. An observational, laboratory-based study of outbreaks of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus in Jeddah and Riyadh, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, 2014. Clin Infect Dis. 2014 doi: 10.1093/cid/ciu812. published online Oct 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Saudi Arabia Ministry of health portal New confirmed coronavirus cases. http://www.moh.gov.sa/en/ccc/pressreleases/pages/default.aspx?PageIndex=1 (accessed Nov 22, 2014).

- 13.Hui DS, Zumla A. Advancing priority research on the Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. J Infect Dis. 2014;209:173–176. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jit591. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Memish ZA, Zumla A, Alhakeem RF. Hajj: infectious disease surveillance and control. Lancet. 2014;383:2073–2082. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60381-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zumla A, Memish ZA, Maeurer M. Emerging novel and antimicrobial-resistant respiratory tract infections: new drug development and therapeutic options. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14:1136–1149. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(14)70828-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]