Abstract

Sialylated structures play important roles in cell communication, and change in a regulated manner during development and differentiation. In this work, we report the main glycosidic modifications that occur during the maturation of porcine tissues, involving the sialylation process as determined with lectins. Sialic acids were identified at several levels in a broad range of cell types of nervous, respiratory, genitourinary and lymphoid origin. Nevertheless, the most contrasting was the type of glycosidic linkage between 5-N-acetyl-neuraminic acid (Neu5Ac) and galactose (Gal) expressed in central nervous system (CNS). Newborn CNS abundantly expressed Neu5Acα2,3Gal, but weakly or scarcely expressed Neu5Acα2,6Gal/GalNAc. Maturation of CNS induced drastic changes in sialic acid expression. These changes include decrease or complete loss of NeuAcα2,3Gal residues, mainly in olfactory structures and brain cortex, which were replaced by their isomers Neu5Acα2,6Gal/GalNAc. In the brain cortex and cerebellum, the increase of Neu5Acα2,6Gal/GalNAc molecules was paralleled by an increase of 5-N-acetyl-9-O-acetyl-neuraminic acid (Neu5,9Ac2). In addition, terminal Gal and N-acetyl-d-galactosamine (GalNAc) residues also increased their expression in adult CNS tissues, but this was more significant in structures forming the encephalic trunk. Our results show that sialylation of porcine CNS is finely modulated throughout the maturation process.

Keywords: Neuraminic acid, Lectins, Glycosylation, Oligosaccharides, Central nervous system, Maturation process, Swine, Histochemistry

1. Introduction

Glycoproteins and glycolipids are major components of eukaryotic cell membranes. Although their biological or physiological functions are known in some cases, the specific biological function of the glycan chains starts to be defined (Pilatte et al., 1993, Varki, 1993). Glycosylation as a covalent modification of proteins is highly diverse and, in many cases, this diversity has been shown to be species, tissue, and cell specific (Lis and Sharon, 1993). Sialic acid is part of a family of nine-carbon carboxylated sugars usually found at the outermost units of vertebrate oligosaccharides, the most common being 5-N-acetyl-neuraminic acid (Neu5Ac), which could be considered as the precursor for almost all others. Additional diversity in sialic acids is generated by the glycosidic linkage at carbon 2, resulting, in most animals, in Neu5Acα2,3 or 2,6 linkages with the hydroxyl groups of galactose (Gal), N-acetyl-d-galactosamine (GalNAc) or N-acetyl-d-glucosamine residues (Schauer and Kamerling, 1997). Lectins, due to their high specificity for carbohydrates of defined structures, have been used in cytochemical and histochemical studies to identify modifications of glycosylation (Alroy et al., 1987, Damjanov, 1987). These studies support the notion that regulated glycosylation is important for cell-to-cell interactions during development and growth (Suzuki et al., 1995). In addition, the use of lectins has led to identify abnormal glycosylation in mammalian tissues under pathological conditions (Ito et al., 1996, Roth et al., 1996). Presence or prevalence of specific saccharidic sequences has been considered indicators of maturity or cell transformation, e.g. the Thomsen–Friedenreich (T and Tn) antigens (Galβ1,3GalNAcα1-0-Ser/Thr and GalNAcα1-0-Ser/Thr, respectively) have been identified as specific structures for immature or transformed cells. Substitution of these antigens with Neu5Ac, forming the cryptic equivalent forms, represents the developmental or activated state of the T- and Tn-containing structures or cells. T and Tn antigens are highly expressed in different organs during fetal life; they have been also detected in most carcinomas, therefore it has been proposed that they represent general carcinoma antigens (Hanisch and Baldus, 1997).

Glycans have been selected by several virus as the preferred attachment sites on their host cells and tissues. Host range, tissue tropism and target cell specificity demonstrated by a particular virus are determined, at least in part, by a stereochemical fit between viral lectins and complementary carbohydrate receptors on host cell surfaces (Lis and Sharon, 1993). In pigs, the pathogenic effect of viruses, such as influenza virus (Kilbourne et al., 1988), coronavirus (Schultze et al., 1996), rotavirus (Rolsma et al., 1998) and rubulavirus (Reyes-Leyva et al., 1993, Reyes-Leyva et al., 1997) depends on a positive organotropism, which is determined by specific interactions between sialic acid-expressing cells and viral adhesion proteins. In general, the infectivity patterns of porcine viruses change with the host maturation stage. For example, rubulavirus induces neurological and respiratory pathologies in newborn and suckling pigs, whereas in adult pigs, it lacks its neurotropism and induces lesions in reproductive tissues (Ramirez et al., 1997). On the base of these findings, we have hypothesized that age-related changes in virus tropism are due to modifications in the tissular expression of sialic acids. The purpose of this study was to use several lectins with well-known sugar specificity, to identify the differences in the sialylation pattern between newborn and adult pigs.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Tissues

Newborn (3 days old) and adult (9 months old) male York–Landrace hybrids, clinically healthy pigs (Sus scrofa domesticus) were used. Pig skulls were gently dissected to separate the encephalic mass, and the central nervous system (CNS) was divided in coronal sections. The brain was preserved together with the ethmoidal cribiform plate to analyze in situ the presence of sugars in the olfactory structures. Tissues were excised and immediately fixed in 3% paraformaldehyde in phosphate-buffered saline (0.01 M sodium phosphate, 0.15 M NaCl; pH 7.4), dehydrated in graded ethanol series and xylol, and embedded in paraffin, according to standard methods (Zeller, 1989). Bone-containing samples were decalcified in 4% ethylenediamine tetraacetic acid during 96 h before their processing for histochemistry (Mori et al., 1995).

2.2. Reagents

Sambucus nigra fraction I (SNA specific for Neu5Acα2,6Gal/GalNAc) (Shibuya et al., 1987) and Maackia amurensis agglutinins (MAA, specific for Neu5Acα2,3Gal) (Konami et al., 1994) were purchased from Boehringer Mannheim Biochemica (Mannheim, Germany); Limulus polyphemus agglutinin (LPA) (specific for Neu5Ac) (Marchialonis and Edelman, 1968) and Arachis hypogaea (peanut) agglutinin (PNA) (specific for T antigen Galβl,3GalNAcα1-0-Ser/Thr) (Pereira et al., 1976) were purchased from Sigma (St. Louis, MO, USA); Macrobrachium rosenbergii lectin (MRL) (specific for Neu5,9Ac2) (Vázquez et al., 1993) and Amaranthus leucocarpus lectin (ALL) (specific for Tn antigen GalNAcα1-0-Ser/Thr) (Zenteno et al., 1992) were purified as previously described (Vázquez et al., 1993; Zenteno and Ochoa, 1988). Lectins were conjugated to NHS-LC-biotin following published methods (Savage et al., 1992), and used at a concentration of 5 μg/ml. Biotinylated tyramide kit and streptavidin-horseradish peroxidase were purchased from Boehringer, and Clostridium perfringens neuraminidase was purchased from Sigma.

2.3. Lectin histochemistry

Paraffin-embedded porcine tissues were prepared at a 6 μm thickness. Tissue sections were deparaffinized following published methods (Zeller, 1989). Sections were then incubated in methanol containing 0.3% H2O2 for 30 min to block the activity of endogenous peroxidase. Hereafter, every step was followed by washing three times with 50 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.6), 150 mM NaCl, 0.5% Tween 20. Sections were incubated with biotin-conjugated lectins for 45 min at room temperature. After this, sections were incubated with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin for 30 min at room temperature. Biotin amplification was performed using biotinylated tyramide for 10 min at room temperature. Sections were then incubated once more with horseradish peroxidase-conjugated streptavidin for 30 min. Colored reaction product was obtained with 0.01% 3,3′-diaminobenzidine tetrahydrochloride (Adams, 1992). To confirm the specificity of the lectin binding, sections were pre-treated with 0.5 IU/ml C. perfringens neuraminidase diluted with 50 mM Tris–HCl buffer (pH 7.6) at 37°C for 1 h, followed by incubation with LPA and PNA lectins. In all conditions, neuraminidase treatment abolished the positive reaction of LPA and increased the reaction with PNA.

3. Results

3.1. Expression of sugars in newborn porcine tissues

3.1. Central nervous system

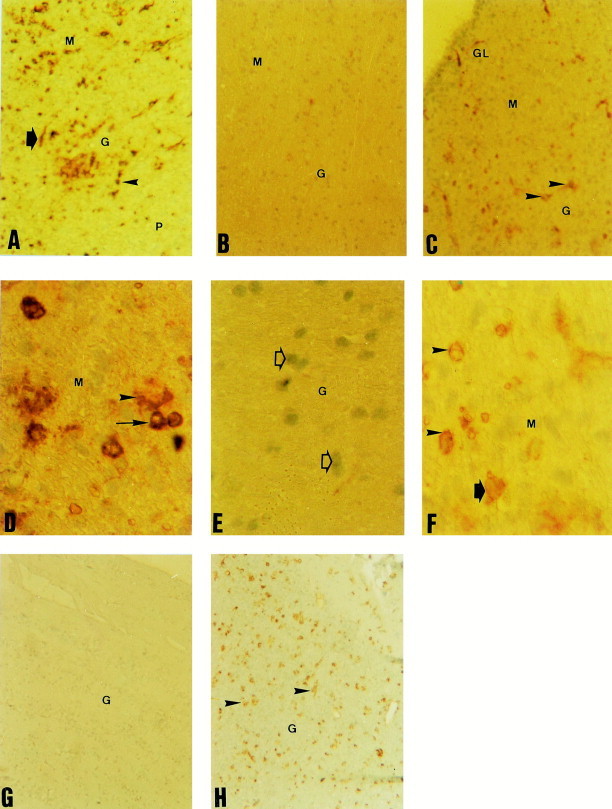

Almost all newborn CNS tissues examined, except spinal cord sections, reacted with LPA and MAA, indicating they express Neu5Ac with α2,3 glycosidic linkage (Table 1 ). These lectins showed an intense homogeneous binding pattern in all the olfactory structures, brain cortex, thalamus, and hypothalamus, but MAA only stained the molecular layer of cerebellum and the pyramidal layer of hippocampus. LPA and MAA intensely stained neuronal somas and fibers (Fig. 1 A,D), whereas glial cells only stained weakly. Most of the newborn CNS tissues did not, or at most scarcely, express sialic acids with α2,6 glycosidic linkage (Fig. 1B,E), except in the midbrain, cerebellum, and pons. Weak expression of Neu5,9Ac2 was found in neural bodies from olfactory structures (Fig. 1C,F), hippocampus, thalamus, midbrain, and cerebellum, but was abundantly expressed in endothelial cells of meningeal blood vessels. Neu5,9Ac2 was the only sialic acid derivative identified at the spinal cord, and exclusively at the dorsal white matter.

Table 1.

Comparative expression of sialic acids in porcine tissuesa

| Newborn |

Adult |

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| LPA | MAA | SNA | MRL | LPA | MAA | SNA | MRL | |

| Central nervous system | ||||||||

| Olfactory nerve (nasal portion) | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Olfactory bulb | 3 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 |

| Olfactory tract | 3 | 3 | 0 | 1 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Piriform lobe brain cortex | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 0 | 2 | 1 |

| Frontal brain cortex | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 |

| Temporal brain cortex | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 1 |

| Occipital brain cortex | 3 | 3 | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Hippocampus | 3 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 2 | 3 | 0 |

| Thalamus | 3 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Hypothalamus | 3 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Meninges | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 |

| Midbrain | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 | 2 | 0 |

| Cerebellum | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 3 | 2 |

| Pons | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Medulla oblongata | 2 | 2 | 1 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Cervical spinal cord | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 |

| Thoracic spinal cord | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Lumbar spinal cord | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 1 |

| Respiratory system | ||||||||

| Nasal mucosa | 3 | 3 | 3 | 2b | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Trachea | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Bronchi | 3 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Lung | 3 | 3 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Genitourinary system | ||||||||

| Kidney | 2 | 2 | 3 | 1 | 2 | 2 | 2 | 0 |

| Testis | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 |

| Epididymis | 1 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 3 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Lymphatic system | ||||||||

| Tonsil | 3 | 3 | 2 | 0 | 3 | 3 | 2 | 1 |

| Mesenteric lymph node | 2 | 1 | 1 | 2 | 3 | 3 | 3 | 1 |

| Spleen | 2 | 1 | 3 | 0 | 2 | 2 | 3 | 3 |

| Thymus | 1 | 1 | 1 | 3 | 1 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

Histochemistry in paraffin-embedded porcine tissue sections was performed using biotin-conjugated lectins and the biotinyltyramide amplification technique (Adams, 1992). The lectins and their sugar specificity were Limulus polyphemus (LPA) (Neu5Ac), Maackia amurensis (MAA) (Neu5Acα2,3Gal), Sambucus nigra (SNA) (Neu5Acα2,6Gal/GalNac), and Macrobrachium rosenbergii (MRL) (Neu5,9Ac2). Lectin binding was evaluated as follows: 0, absent; 1 low reaction observed in dispersed cells; 2, medium, presented in less than one-half of the tissue section; and 3, high intensity, observed homogeneously in a tissue section.

Olfactory mucosa.

Fig. 1.

Sialic acid expression in newborn (A–F) and adult (G–H) olfactory bulb. Histochemistry was performed following the biotinyltyramide amplification technique (Adams, 1992) using biotin-conjugated lectins from M. amurensis (MAA) (Neu5Acα2,3Gal specific), S. nigra (SNA) (Neu5Acα2,6Ga/GalNAc), and M. rosenbergii (MRL) (Neu5,9Ac2). Tissue sections taken across the glomerular (GL), mitral (M), granular (G) and periventricular (P) layers of the olfactory bulb. (A) Representative tissue section of olfactory bulb with high level of Neu5Acα2,3Gal expression. Intense positive reaction to MAA was observed in neurons throughout the tissue, i.e. pyramidal (arrow), mitral (arrow heads) and granular neurons. Magnification, 80×. (B) Representative tissue section with null expression of Neu5Acα2,6Gal/GalNAc molecules, negative to SNA. Magnification, 80×. (C) Example of tissue sections with a weak level of Neu5,9Ac2 expression. Slight positive reaction to MRL was identified in mitral (arrowheads) and granular neurons. Magnification, 80×. (D) Detail of (A), note the intense staining of neural bodies (arrows) and axons (arrowhead) with MAA. Magnification, 320×. (E) Detail of (B), note the lack of positive staining with SNA, the nucleus of negative cells were counterstained with hematoxyline (arrow). Magnification, 320×. (F) Detail of (C), note the slight staining around the nucleus of granular (arrowhead) and mitral (arrow) neurons. Magnification, 320×. (G) Maturation of porcine CNS induces drastic changes in sialic acid expression. Note the complete lack of reaction with MAA. Magnification, 80×. (H) Adult olfactory bulb now expresses high levels of Neu5Acα2,6Gal/GalNAc molecules. SNA mainly reacted with granular and pyramidal neurons (arrows). Magnification, 320×.

PNA and ALL showed similar affinity patterns in almost all CNS tissues. They did not interact at all with olfactory structures, brain cortex nor spinal cord; weakly stained midbrain and just stained diffused cells at thalamus, hypothalamus and meninges (Table 2 ). However, they showed staining differences in other tissues, such as cerebellum, where ALL intensely stained almost all small neurons of the molecular layer, whereas PNA stained only few dispersed cells. In the same manner, the medulla oblongata expressed low levels of Tn antigens, but lacked T antigens.

Table 2.

Expression of T and Tn antigens in porcine tissuesa

| Newborn |

Adult |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| PNA | ALL | PNA | ALL | |

| Central nervous system | ||||

| Olfactory nerve | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Olfactory bulb | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Olfactory tract | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Piriform lobe brain cortex | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Frontal brain cortex | 0 | 0 | 1 | 0 |

| Temporal brain cortex | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Occipital brain cortex | 0 | 0 | 1 | 2 |

| Hippocampus | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Thalamus | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Hypothalamus | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Meninges | 1 | 1 | 2 | 2 |

| Midbrain | 2 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Cerebellum | 1 | 2 | 1 | 0 |

| Pons | 0 | 0 | 2 | 2 |

| Medulla oblongata | 0 | 1 | 1 | 2 |

| Cervical spinal cord | 0 | 0 | 0 | 2 |

| Respiratory system | ||||

| Nasal mucosa | 0 | 0 | 1 | 1 |

| Trachea | 2 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Bronchus | 2 | 2 | 2 | 2 |

| Lung | 1 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| Genitourinary system | ||||

| Kidney | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Testis | 2 | 3 | 0 | 0 |

| Epididymis | 1 | 1 | 0 | 0 |

| Lymphatic system | ||||

| Tonsil | 1 | 1 | 2 | 1 |

| Mesenteric lymph node | 2 | 3 | 1 | 1 |

| Spleen | 2 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

| Thymus | 3 | 2 | 1 | 1 |

Histochemistry in paraffin-embedded porcine tissue sections was performed using biotin-conjugated lectins and the biotinyltyramide amplification technique (Adams, 1992). The lectins used were: peanut agglutinin (PNA) (specific for T antigen: Galβ1,3GalNAcα1,0Ser/Thr) and Amaranthus leucocarpus (ALL) (specific for Tn antigen: GalNAcα1,0Ser/Thr). Lectin binding was evaluated as follows: 0, absent; 1 low reaction observed in dispersed cells; 2, medium, presented in less than one-half of the tissue section; and 3, high intensity, observed homogeneously in a tissue section.

3.1. Respiratory system

Neu5Ac-, Neu5Acα2,3Gal- and Neu5Acα2,6Gal/GalNAc-containing glycoconjugates were identified in the nasal mucosa, trachea, bronchi, and lungs. Very similar distributions were found at the apical surface of the respiratory epithelium and submucosal glands. Low to middle expression of Neu5,9Ac2 was found throughout the lower respiratory tract epithelium as well as in submucosal glands of the olfactory mucosa (Table 1). PNA reacted with epithelial and connective cells of both trachea and bronchi, as well as with few dispersed endothelial cells at the periphery of the lungs great blood vessels. ALL reacted with dispersed epithelial cells from bronchi, trachea, and the lower respiratory tract serosa (Table 2).

3.1. Genitourinary tract

All the lectins tested reacted with the kidney. LPA, MAA, and SNA presented a broad homogeneous staining; MRL just reacted with cortical cells, while PNA and ALL recognized cells of the tubular epithelium at the kidney medulla. In the testis, LPA and MAA reacted with epithelial cells of seminiferous tubes, SNA stained capsule and blood vessels, and MRL stained diffused endothelial cells. PNA and ALL stained blood vessels, the latter also intensely stained mononuclear cells at interstitial tissue. Epididymis of newborn pigs expressed low levels of Neu5Acα2,3Gal and Neu5,9Ac2 at the tubular epithelium; as well as T and Tn antigens at interstitial blood vessels, but lacked Neu5Acα2,6Gal/GalNAc (Table 1).

3.1. Lymphatic system

Broad expression of sialic acid was observed in most of the lymphoid tissues examined. Tonsils expressed more Neu5Acα2,3Gal than its isomer Neu5Acα2,6Gal/GalNAc; both of them were identified in germinal cells of the crypts. This organ did not express Neu5,9Ac2, but expressed low levels of T and Tn antigen in connective tissue and blood vessels. Lymphonodi expressed low levels of Neu5Ac with both α2,3 and α2,6 glycosidic linkage, staining with lectins was mainly evidenced on mononuclear cells, but some dendritic and interstitial cells were also stained. Mononuclear cells and interstitial tissues expressed Neu5,9Ac2. A great proportion of mononuclear cells showed high intensity staining with ALL, but only medium intensity with PNA. Almost all the lectins showed a broad distribution pattern at spleen with diverse staining levels, but SNA showed the highest intensity of all. The thymus showed very low staining with LPA, MAA, and SNA, and high staining with MRL, indicating the presence of Neu5,9Ac2 in this cell (Table 1); high expression of T and Tn antigens were indicated by the positive staining of PNA and ALL, respectively (Table 2).

3.2. Expression of sugars in adult porcine tissues

3.2. Central nervous system

Sialic acid distribution in adult CNS tissues showed drastic differences to that of newborn animals. Indeed, a notable decrease in Neu5Acα2,3Gal expression was found in ten of the 18 CNS tissues examined; however, it was more important in structures involved in olfactory perception, i.e. olfactory nerve, bulb and tract; and piriform lobe brain cortex, which did not express Neu5Acα2,3Gal moieties at all (Fig. 1A), although staining with LPA and MAA increased in medulla oblongata and dispersed positive cells were now identified in the cervical spinal cord. The other most important change was the identification of Neu5Acα2,6Gal/GalNAc residues in adult olfactory structures and brain cortex, which were totally absent in the newborn ones. Other nervous tissues also showed a marked increase in this sialic acid derivative. In general, Neu5Acα2,6Gal over expression paralleled Neu5Acα2,3Gal downregulation (Table 1). Expression of Neu5,9Ac2 also increased with CNS maturation. This acetylated sialic acid was now observed in all regions of the brain cortex, pons and medulla oblongata, as well as in the lateral fascicles of spinal cord regions. In other tissues, such as cerebellum and olfactory bulb, the staining intensity also increased. MRL staining disappeared in mature midbrain, thalamus and hippocampus. It is important to note that brain cortex maturation involved the new expression of both Neu5Acα2,6Gal and Neu5,9Ac2 molecules. Expression of terminal Gal/GalNAc residues (T and Tn antigens) also increased in mature CNS tissues, this change was observed in several nervous tissues, but was more notable in structures forming the encephalic trunk (Table 2).

3.2. Respiratory system

In general, there were no differences in the expression of Neu5Ac, Neu5Acα2,3Gal nor Neu5Acα2,6Gal residues between newborn and adult respiratory tissues. However, the lower respiratory tract epithelium became negative to MRL in adult pigs, indicating lack of Neu5,9Ac2, except for the nasal mucosa epithelium, which became positive to MRL, at both the turbinate and olfactory regions (Table 1). Some epithelial cells in the turbinate nasal mucosa became positive to PNA and ALL lectins. No other significant change was observed in the respiratory tract (Table 2).

3.2. Genitourinary tract

Adult kidneys did not reveal significant differences with respect to piglets, although they showed a reduced expression of Neu5Acα2,6Gal/GalNAc and became negative to MRL (Table 1), PNA and ALL (Table 2). Testis maturation produced a notable increase in LPA and MAA binding sites; these were identified on germ cells and epithelial cells of seminiferous and afferent tubules, as well as in some interstitial cells. In addition, testes became negative to MRL (Table 1), PNA and ALL (Table 2). Adult epididymis also showed a notable increase in Neu5Acα2,3Gal expression, positive cells were broadly distributed in the tubule wall, interstitial tissue and blood vessel endothelium. Lack of reaction with PNA and ALL was also observed in the blood vessels of adult epididymis (Table 2).

3.2. Lymphatic system

In general, the expression of sialic acids with 2,3 or 2,6 glycosidic linkage increased with maturation of lymphoid organs, except in the thymus where just some Neu5Ac α2,6/GalNAc positive cells were identified. Other relevant findings were the identification of MRL positive mononuclear cells in tonsils and spleen, and the lack of these MRL positive cells in the mesenteric lymph node and thymus. Regarding PNA and ALL binding, reduction in the proportion of positive cells was observed in spleen, thymus, and lymph node.

4. Discussion

In this study, we performed a screening of sialylated structures in newborn and adult porcine organs to identify the possible role of maturation as determinant of the rate and type of sialylation. As our results indicate, the most evident modifications on sialylation occurred in the nervous system. The terminal position of sialic acid residues on animal glycoconjugates makes of them critical components of ligands recognized by a variety of animal, plant and microbial lectins (Sharon and Lis, 1997). The lectin from L. polyphemus recognizes sialic acid irrespective of the glycosidic linkage (Marchialonis and Edelman, 1968); for this reason, its recognition pattern, in pigs, is not modified in most of the organs tested. However, recognition of M. amurensis (specific for Neu5Acα2,3Gal) (Konami et al., 1994) and S. nigra fraction I (specific for Neu5Acα2,6Gal/GalNAc) (Shibuya et al., 1987) lectins is modified by the maturation process. Neu5Acα2,3Gal is preferentially identified in neonatal nervous system and adult genital organs, whereas Neu5Acα2,6Gal appear to be more prevalent in adult nervous tissues. Another modification of sialic acid is its 9-O-acetylation, which is specifically recognized by MRL (Vázquez et al., 1993). Although Neu5,9Ac2 was expressed at low levels in newborn pigs, it showed a broad distribution in diverse neonatal organs, but most of them became MRL negative after maturation; except for nervous tissues that increase their Neu5,9Ac2 expression. Neu5,9Ac2 occurred only in particular regions of neonatal thymus medulla and germinal centers of lymphonodi. Several studies have shown that 9-O-acetylation is commonly seen in cells of neuroectodermal origin and seems to play a role in the migration of developing neurons in the embryonic brain (Blum and Barnstable, 1987), and in the organization and growth of cones and neurites (Araujo et al., 1997). It has been shown that the concentration of Neu5,9Ac2 residues in CD4+ T lymphocytes is modified during activation and maturation processes (Krishna and Varki, 1997). In the porcine lymphatic system, this sugar residue was identified in cells from spleen, lymph node and tonsils from adult organisms, confirming that memory lymphocyte subsets present in germinal centers possess Neu5,9Ac2.

Expression of T and Tn antigens was restricted to mesencephalic structures within neonatal CNS; however, their expression was broader distributed in adult CNS. These antigens showed attenuated levels of expression in other adult organ systems, including genitourinary and lymphoid. This suggests that these antigens may exist in a cryptic sialylated form in most organ systems in adult pig. A. leucocarpus lectin has been used to identify murine and human lymphocytes in the late stages of maturation and its interaction with the GalNAc moiety is not modified by the presence of sialic acid (Zenteno et al., 1992, Lascurain et al., 1994).

Sialic acids occur at terminal positions of the carbohydrate groups of glycoproteins and glycolipids, the transfer of sialic acids from CMP-NeuAc to these positions is catalyzed by a family of sialyltransferases (Harduin-Lepers et al., 1995). Changes in the expression of sialyltransferases have been previously described during maturation of cells as well as during development. As an example, during weaning, the epithelium of the mammalian small intestine undergoes a glycoform switch from predominantly sialylated glycoconjugates to those expressing fucose at their termini. Developmental regulation of β-galactoside α2,6-sialyltransferase (ST6Gal I; EC 2.4.99.1) in rat small intestine epithelium has been reported (Vertino-Bell et al., 1994). Induction of ST6Gal I by glucocorticoids in suckling rat small intestine has also been reported (Kolinska et al., 1996, Hamr et al., 1997). Furthermore, evidence for the regulated expression of the Galβ1-3GalNAc α2,3-sialyltransferase (ST3Gal I; EC 2.4.99.4) in developing thymocytes has been presented (Gillespie et al., 1993). Cortical regions of the thymus composed of immature thymocytes show low levels of ST3Gal I mRNA, whereas medullary regions of the thymus composed of mature thymocytes overexpress the enzyme. The relevance of the modifications in the sialylation process is not yet well known; however, it is necessary to assume that sialic acids could participate not only as targets for specific pathogens, but as important molecules in the regulation of the immune system (Pereira et al., 1976). However, the possibility that a specific modification of the porcine sialyltransferase activity could be modulated during maturation by sexual steroids cannot be ruled out (Vandamme et al., 1993, Hamr et al., 1997).

Lectin histochemistry possesses its own limitations; indeed, we were unable to elucidate the tissue distribution of N-glycolylneuraminic acid or poly-Neu5Acα2,8Neu5Ac, because of the lack of specific lectins against these molecules, well known to be expressed in porcine glycoconjugates (Schauer and Kamerling, 1997).

Acknowledgements

The authors thank Marı́a Eugenia Sánchez and Oscar Garcı́a for their help with the histochemical techniques. This work was supported by CONACYT (Grants 3228P-B and 2151PM) and PAPIIT, UNAM (IN209295) Mexico.

References

- Adams J.C. Biotin amplification of biotin and horseradish peroxidase signals in histochemical stains. J. Histochem. Cytochem. 1992;40:1457–1463. doi: 10.1177/40.10.1527370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alroy J., Goyal V., Skutelsky E. Lectin histochemistry of mammalian endothelium. Histochemistry. 1987;86:603–607. doi: 10.1007/BF00489554. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Araujo H., Menezes M., Mendez-Otero R. Blockage of 9-O-acetyl gangliosides induces microtubule depolymerization in growth cones and neurites. Eur. J. Cell. Biol. 1997;72:202–213. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blum A.S., Barnstable C.J. O-Acetylation of a cell-surface carbohydrate creates discrete molecular patterns during neural development. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1987;84:8716–8720. doi: 10.1073/pnas.84.23.8716. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Damjanov I. Lectin cytochemistry and histochemistry. Lab. Invest. 1987;57:5–20. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gillespie W., Paulson J.C., Kelm S., Pang M., Baum L.G. Regulation of alpha 2,3-sialyltransferase expression correlates with conversion of peanut agglutinin (PNA)+ to PNA− phenotype in developing thymocytes. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;268:3801–3804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hamr A., Delannoy P., Verbert A., Kolinska J. The hydrocortisone-induced transcriptional down-regulation of beta-galactoside alpha2,6-sialyltransferase in the small intestine of suckling rats is suppressed by mitepristone (RU-38.486) J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1997;60:59–66. doi: 10.1016/s0960-0760(96)00170-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hanisch F.G., Baldus S.E. The Thomsen–Friedenreich (TF) antigen: a critical review on the structural, biosynthetic and histochemical aspects of a pancarcinoma-associated antigen. Histol. Histopathol. 1997;12:263–281. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harduin-Lepers A., Recchi M.A., Delannoy P. 1994, the year of sialyltransferases. Glycobiology. 1995;5:741–758. doi: 10.1093/glycob/5.8.741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ito N., Yokota M., Nagaike C., Morimura Y., Hatake K., Matsunaga T. Histochemical demonstration and analysis of poly-N-acetyllactosamine structures in normal and malignant human tissues. Histol. Histopathol. 1996;11:203–214. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilbourne E.D., Taylor A.H., Whitaker C.W., Sahai R., Caton A.J. Hemagglutinin polymorphism as the basis for low- and high-yield phenotypes of swine influenza virus. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 1988;85:7782–7785. doi: 10.1073/pnas.85.20.7782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kolinska J., Zakostelecka M., Hamr A., Baudysova M. Co-ordinate expression of beta- galactoside alpha 2,6-sialyltransferase mRNA and enzyme activity in suckling rat jejunum cultured in different media: transcriptional induction by dexamethasone. J. Steroid Biochem. Mol. Biol. 1996;58:289–297. doi: 10.1016/0960-0760(96)00033-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konami Y., Yamamoto K., Osawa T., Irimura T. Strong affinity of Maackia amurensis hemagglutinin (MAH) for sialic acid-containing Ser/Thr-linked carbohydrate chains of N-terminal octapeptides from human glycophorin A. FEBS Lett. 1994;342:334–338. doi: 10.1016/0014-5793(94)80527-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krishna M., Varki A. 9-O-Acetylation of sialomucins: a novel marker of murine CD4 T cells that is regulated during maturation and activation. J. Exp. Med. 1997;185:1997–2013. doi: 10.1084/jem.185.11.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lascurain R., Chavez R., Gorocica P., Perez A., Montaño L.F., Zenteno E. Recognition of a CD4+ mouse medullary thymocyte subpopulation by Amaranthus leucocarpus lectin. Immunology. 1994;83:410–413. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lis H., Sharon N. Protein glycosylation. Structural and functional aspects. Eur. J. Biochem. 1993;218:1–27. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb18347.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchialonis J.J., Edelman G.M. Isolation and characterization of a hemagglutinin from Limulus polyphemus. J. Mol. Biol. 1968;32:453–457. doi: 10.1016/0022-2836(68)90022-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mori I., Komatsu T., Takeuchi K., Nakakuki K., Sudo M., Kimura Y. Parainfluenza virus type I infects olfactory neurons and establishes long-term persistence in the nerve tissue. J. Gen. Virol. 1995;76:1251–1254. doi: 10.1099/0022-1317-76-5-1251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira M.E.A., Kabat E.A., Lotan R., Sharon N. Immunochemical studies on the specificity of the peanut (Arachis hypogaea) agglutinin. Carbohydr. Res. 1976;51:107–118. doi: 10.1016/s0008-6215(00)84040-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pilatte Y., Bignon J., Lambré C.R. Sialic acids as important molecules in the regulation of the immune system: pathophysiological implications of sialidases in immunity. Glycobiology. 1993;3:201–217. doi: 10.1093/glycob/3.3.201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez H., Hernández-Jáuregui P., Reyes-Leyva J., Zenteno E., Moreno-López J., Kennedy S. Lesions in the reproductive tract of boars experimentally infected with porcine rubulavirus. J. Comp. Pathol. 1997;117:237–252. doi: 10.1016/s0021-9975(97)80018-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Leyva J., Hernández-Jáuregui P., Montaño L.F., Zenteno E. The porcine paramyxovirus LPM specifically recognizes sialylα(2,3)lactose-containing structures. Arch. Virol. 1993;133:195–200. doi: 10.1007/BF01309755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Leyva J., Espinosa B., Hernández J., Zenteno R., Vallejo V., Hernández-Jáuregui P., Zenteno E. NeuAcα2,3Gal-glycoconjugate expression determines cell susceptibility to the porcine rubulavirus LPMV. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B. Comp. Biochem. 1997;118B:327–332. doi: 10.1016/s0305-0491(97)00164-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolsma M.D., Kuhlenschmidt T.B., Gelberg H.B., Kuhlenschmidt M.S. Structure and function of a ganglioside receptor for porcine rotavirus. J. Virol. 1998;72:9079–9091. doi: 10.1128/jvi.72.11.9079-9091.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roth J., Zuber C., Komminoth P., Sata T., Li W.P., Heitz P.U. Applications of immunogold and lectin-gold labeling in tumor research and diagnosis. Histochem. Cell Biol. 1996;106:131–148. doi: 10.1007/BF02473207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Savage D., Mattson G., Desai S., Nielander G., Morgensen S., Conklin E. Avidin–Biotin Chemistry: A Handbook. Pierce Chemical; Rockford IL: 1992. [Google Scholar]

- Schauer R., Kamerling J.P. Chemistry, biochemistry and biology of sialic acids. In: Montreuil J., Vliegenthart J.F.G., Schachter H., editors. Glycoproteins II. Elsevier Science; Amsterdam: 1997. pp. 243–402. [Google Scholar]

- Schultze B., Krempl C., Ballesteros M.L., Shaw L., Schauer R., Enjuanes L., Herrler G. Transmisible gastroenteritis coronavirus, but not the related porcine respiratory coronavirus, has a sialic acid (N-glycolylneuraminic acid) binding activity. J. Virol. 1996;70:5634–5637. doi: 10.1128/jvi.70.8.5634-5637.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharon N., Lis H. Microbial lectins and their glycoprotein receptors. In: Montreuil J., Vliegenthart J.F.G., Schachter H., editors. Glycoproteins II. Elsevier Science; Amsterdam: 1997. pp. 475–506. [Google Scholar]

- Shibuya N., Goldstein I.J., Broekaert W.F., Nsimba-Lubaki M., Peeters B., Peumans W.P. The elderberry (Sambucus nigra L.) bark lectin recognizes the Neu5Ac(alpha2-6)Gal/GalNAc sequence. J. Biol. Chem. 1987;262:1596–1601. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suzuki T., Kitajima K., Inoue S., Inoue Y. N-Glycosylation/deglycosylation as a mechanism for the post-translational modification/remodification of proteins. Glycoconjugate J. 1995;12:183–193. doi: 10.1007/BF00731318. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vandamme V., Pierce A., Verbert A., Delannoy P. Transcriptional induction of beta-galactoside alpha-2,6-sialyltransferase in rat fibroblast by dexamethasone. Eur. J. Biochem. 1993;211:135–140. doi: 10.1111/j.1432-1033.1993.tb19879.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varki A. Biological roles of oligosaccharides: all of the theories are correct. Glycobiology. 1993;3:97–130. doi: 10.1093/glycob/3.2.97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vázquez L., Massó F., Rosas P., Montaño L.F., Zenteno E. Purification and characterization of a lectin from Macrobrachium rosenbergii (Crustacea, Decapoda) hemolymph. Comp. Biochem. Physiol. B. Comp. Biochem. 1993;105B:617–623. [Google Scholar]

- Vertino-Bell A., Ren J., Black J.D., Lau J.T. Development regulation of beta-galactoside alpha 2,6-sialyltransferase in small intestine epithelium. Dev. Biol. 1994;165:126–136. doi: 10.1006/dbio.1994.1240. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zeller R. Fixation, embedding and sectioning of tissues embryos and single cells. In: Ausubel F.M., Brent R., Kingston R.A., Moore D.D., Seidman J.G., Smith J.A., Strohl K., editors. Current Protocols in Molecular Biology. Greene Publishing and Wiley Interscience; New York: 1989. pp. 14.1.1–14.1.8. [Google Scholar]

- Zenteno E., Ochoa J.L. Purification of a lectin from Amaranthus leucocarpus by affinity chromatography. Phytochemistry. 1988;27:313–317. [Google Scholar]

- Zenteno E., Lascurain R., Montaño L.F., Vázquez L., Debray H., Montreuil J. Specificity of Amaranthus leucocarpus lectin. Glycoconjugate J. 1992;9:204–208. doi: 10.1007/BF00731166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]