We would like to comment on a recent study reporting the recreation of the 1918 influenza “paleovirus”.1 Beyond this scientific tour de force, these experiments raise huge ethical concerns.2

The medical justifications for such an exercise are open to debate. First, it is not certain that a better understanding of the virus' pathogenesis in a mouse model would be helpful for treating influenza infections in human beings. Second, the predicted efficacy of neuraminidase inhibitors and immunogenicity of H1N1-derived vaccines have already been demonstrated in recombinant influenza A viruses bearing the appropriate H1 and N1 genes.3, 4 Third, to have a pandemic flu vaccine available on the market in the shortest possible time, the European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products encourages manufacturers to work on a core dossier using a mock-up strain.5 However, because of the danger that the virulent 1918 flu strain presents, the strain will never be distributed worldwide for such a purpose.

By contrast, the risks of such an exercise are real. First, it is astonishing that this virus has been manipulated in a biosafety level (BSL) 3 laboratory and not at a higher level of containment. Severe acute respiratory syndrome virus escapes from BSL3 labs were reported.6 In addition, the H2N2 1957 pandemic strain was accidentally sent to 3700 reference laboratories in 2005.7 The 1918 flu virus poses a high risk of life-threatening disease, with high spreading aerosol transmission and without enough therapeutic stocks of antivirals available for mass treatment, and thus should have been classified as a BSL4 agent, and even contained in a special high security facility—as in the case of variola virus8—until its expected destruction.

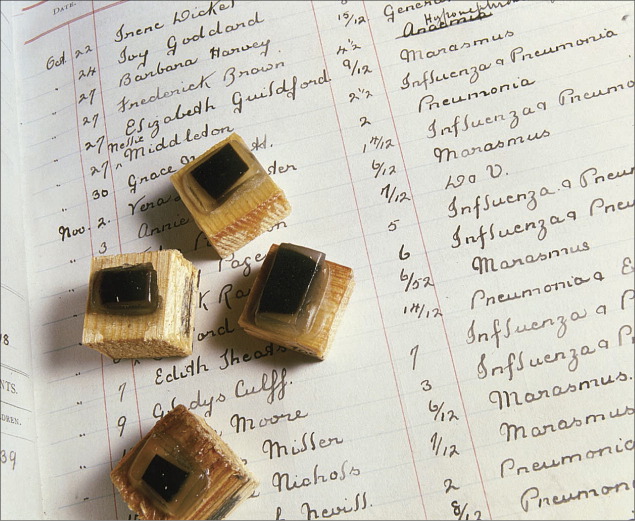

Lung tissue samples from 1918

© 2006 James King-Holmes/Science Photo Library

Furthermore, the reconstruction of the 1918 pandemic flu virus could be viewed as research with potential for dual use (ie, for civil and military gains) and could even be interpreted as an intentional reinforcement of a highly pathogenic virus, which is forbidden by the Biological Weapons Convention that was agreed in 1972.9

In addition, the complete publication of the influenza paleovirus genome paves the way for the replication of the work and could be hijacked by rogue states or terrorist organisations to produce biological weapons.

It is not the first time that controversy has followed potentially harmful experiments with viruses. Unsuccessful Russian attempts to dig up live variola virus from cadavers buried in the Siberian permafrost were reported.10 After, the publication of data describing the increased pathogenicity of ectromelia virus expressing interleukin 4,11 genetic engineering of interleukin 4-expressing vaccinia or cowpox viruses to check the efficiency of smallpox vaccines was forbidden by French ethical committees.

For transparency, and to prevent any suspicion of state interests in dual-use research activities, responsible scientists should now submit to, and comply with, ethical evaluation of their projects at a supranational level for compliance with arms control laws, using either existing international organisations—eg, WHO, the UN—or non-governmental international scientific societies—eg, the Nobel institution.

References

- 1.Tumpey TM, Basler CF, Aguilar PV. Characterization of the reconstructed 1918 Spanish influenza pandemic virus. Science. 2005;310:77–80. doi: 10.1126/science.1119392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.van Aken J. Risks of resurrecting 1918 flu virus outweigh benefits. Nature. 2006;439:266. doi: 10.1038/439266a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tumpey TM, Garcia-Sastre A, Mikulasova A. Existing antivirals are effective against influenza viruses with genes from the 1918 pandemic virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2002;99:13849–13854. doi: 10.1073/pnas.212519699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tumpey TM, Garcia-Sastre A, Taubenberger JK, Palese P, Swayne DE, Basler CF. Pathogenicity and immunogenicity of influenza viruses with genes from the 1918 pandemic virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2004;101:3166–3171. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0308391100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.European Agency for the Evaluation of Medicinal Products. Committee for Proprietary Medicinal Products Guideline on dossier structure and content for pandemic influenza vaccine marketing authorization application. http://www.emea.eu.int/pdfs/human/vwp/471703en.pdf (accessed Mar 29, 2006)

- 6.Anon The 1918 flu virus is resurrected. Nature. 2005;437:794–795. doi: 10.1038/437794a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nelson R. Influenza A H2N2 saga remains unexplained. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:332. doi: 10.1016/s1473-3099(05)70126-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Leduc JW, Jahrling PB. Strengthening national preparedness for smallpox: an update. Emerg Infect Dis. 2001;7:155–157. doi: 10.3201/eid0701.700155. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.United Nations Convention on the prohibition of the development, production and stockpiling of bacteriological (biological) and toxin weapons and on their destruction. http://disarmament.un.org/wmd/bwc/BWCtext.htm (accessed Mar 23, 2006)

- 10.Enserink M, Stone R. Public health. Dead virus walking. Science. 2002;295:2001–2005. doi: 10.1126/science.295.5562.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Jackson RJ, Ramsay AJ, Christensen CD, Beaton S, Hall DF, Ramshaw IA. Expression of mouse interleukin-4 by a recombinant ectromelia virus suppresses cytolytic lymphocyte responses and overcomes genetic resistance to mousepox. J Virol. 2001;75:1205–1210. doi: 10.1128/JVI.75.3.1205-1210.2001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]