Highlights

-

•

Neutrophils represent a cellular source of chemokines.

-

•

Neutrophils recruit and activate, via chemokines, discrete leukocyte populations.

-

•

Neutrophils, in virtue of their capacity to recruit innate and adaptive immunity cells via chemokines, potentially orchestrate sophisticated immune responses.

-

•

Neutrophil-derived chemokines contribute to the pathogenesis of infectious and non-infectious diseases.

Keywords: Neutrophils, Chemokines, Innate immunity, Adaptive immunity, Infections, Tumors, Immune-mediated diseases

Abstract

During recent years, it has become clear that polymorphonuclear neutrophils are remarkably versatile cells, whose functions go far beyond phagocytosis and killing. In fact, besides being involved in primary defense against infections–mainly through phagocytosis, generation of toxic molecules, release of toxic enzymes and formation of extracellular traps–neutrophils have been shown to play a role in finely regulating the development and the evolution of inflammatory and immune responses. These latter neutrophil-mediated functions occur by a variety of mechanisms, including the production of newly manufactured cytokines.

Herein, we provide a general overview of the chemotactic cytokines/chemokines that neutrophils can potentially produce, either under inflammatory/immune reactions or during their activation in more prolonged processes, such as in tumors. We highlight recent observations generated from studying human or rodent neutrophils in vitro and in vivo models. We also discuss the biological significance of neutrophil-derived chemokines in the context of infectious, neoplastic and immune-mediated diseases. The picture that is emerging is that, given their capacity to produce and release chemokines, neutrophils exert essential functions in recruiting, activating and modulating the activities of different leukocyte populations.

1. Introduction

Chemokines are 8- to 12-kDa polypeptides, sharing 20–70% homology in amino acid sequence, that are classified into four families (XC, CC, CXC and CX3C families) based on the positioning of their initial cysteine residues [1]. CXC and CC chemokines represent the two major and most studied groups, being the CXC chemokines further divided into two subfamilies, depending on the presence of the glutamate-leucine-arginine (ELR) motif preceding the first two cysteins [2]. CXC ELR-expressing chemokines are mostly chemotactic for neutrophils and include, among other members, CXCL8/IL-8, CXCL1/growth-related gene product-α (GRO-α), CXCL2/macrophage inflammatory protein 2-alpha (MIP-2α)/GROβ, CXCL3/MIP-2β/GROγ and CXCL5/epithelial cell-derived and neutrophil-activating 78-amino acid peptide (ENA-78) [1], [3], [4]. By contrast, CXCL members lacking the ELR motif, such as CXCL10/interferon (IFN)γ-inducible protein of 10 kDa (IP-10), CXCL9/monokine induced by IFNγ (MIG) and CXCL11/IFNγ-inducible T-cell α chemoattractant (I-TAC), act instead on natural killer (NK) and activated T cells [1], [5], [6]. CXC chemokines containing the ELR motif also display a potent angiogenic activity, while CXC chemokines lacking the ELR motif are angiostatic [2]. The CC family includes chemokines such as CCL2/monocyte chemotactic protein/MCP-1, CCL3/macrophage inflammatory protein (MIP)-1α, CCL4/MIP-1β, CCL5/Regulated on Activation, Normal T cells Expressed and Activated (RANTES), CCL7/MCP-3, CCL17/Thymus and activation regulated chemokine (TARC), CCL18/Pulmonary and activation regulated chemokine (PARC), CCL19/MIP-3β and CCL20/MIP-3α, that are mostly chemotactic and stimulatory for monocytes, macrophages, dendritic cells (DCs), T cells, NK cells, eosinophils and basophils [1], [3], [4], [7]. Chemokines are mostly secreted into the extracellular space as soluble factors or bound to the extracellular matrix, thus forming transient or stable concentration gradients, respectively [1]. They promote increased cell motility and directional migration upon binding to their corresponding cell-surface, seven transmembrane-spanning receptors (e.g., CXCRs and CCRs), that signal through G protein-mediated cascades [8], [9]. Based on the pattern of receptors expressed, discrete cell populations are specifically recruited by different chemokines [1], [10]. Usually a given leukocyte population has receptors for, and responds to, different chemokines [11]. Besides regulating leukocyte trafficking, and therefore coordinating immune responses, chemokines play an important role also in regulating T and B cell-development [12], modulating angiogenesis [13], [14] and influencing tumor growth [15]. Although virtually all cell types may release chemokines, innate and adaptive immunity cells, including polymorphonuclear neutrophils, represent the major source of them [1], [16], especially in inflammatory (infectious and/or non-infectious) [17], [18] or tumor settings [17], [19].

Neutrophils are not anymore viewed as simple “suicide” killer cells at the bottom of the hierarchy of immune response [20], [21]. The last two decades have, in fact, witnessed a new wave of exciting studies about the capacity of neutrophils to express a number of genes whose products lie at the core of crucial biological processes, including innate immune responses [21], [22]. In such regard, neutrophils have been shown to express and produce a variety of chemokines (Table 1 ) upon activation by microenvironmental stimuli such as microbial agents or their products, including ligands for Toll-like receptors (TLRs) or other pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs), even in a timely- and specific stimulus-dependent manner [16], [22], [23]. In addition to amplify their production of chemokines by autocrine loops [23], [24], [25], neutrophils have been also shown to positively/negatively modulate the effects of the chemokines present in the microenvironment by releasing enzymes with proteolytic activities, either in association with extracellular traps [26] or not [27]. Therefore, in the context of an inflammatory reaction that has the ultimate goal to kill and remove the invading pathogens, neutrophils may recruit, via chemokine release, discrete innate and adaptive immunity cells to optimally orchestrate the most efficacious immune response. Neutrophils themselves have been shown to migrate into the inflammatory site in tightly regulated waves, which are mediated by chemoattractant/chemokine cascades released by activated resident tissue cells and/or previously activated neutrophils or macrophages [23], [28], [29].

Table 1.

Chemokines that human and murine neutrophils can potentially express and/or produce.

Expression and/or production of the listed chemokines have been detected in human and mouse neutrophils by gene expression techniques, IHC, enzyme-linked immunoadsorbent assays (ELISAs) or biological assays.

(?): It indicates controversial data.

ND: Not reported in the literature.

Detected in rat.

Mouse only.

It refers to studies performed at the mRNA level only.

Human only.

In the following sections, we will highlight recent literature concerning the role of chemokines derived by human neutrophils in shaping the innate and adaptive immune response, either towards infections, or in the context of other pathological conditions such as cancer or immune-mediated diseases. We will also describe findings generated in in vivo mouse models, which either extend, or uncover, differences between species [10], [22]. For a more broad comprehension of the knowledge existing in the field, the readers may refer to previously published, very exhaustive, reviews [16], [28], [30].

2. Neutrophil-derived chemokines in immune responses and infections

Most studies indicate that neutrophils upregulate chemokine-encoding genes and/or release chemokines when appropriately stimulated [30]. Hence, the pattern of chemokines released by neutrophils is strictly dependent on the type of stimulus and/or associated to a specific inflammatory/immunological context, in vitro and in vivo. A large but non-exhaustive list of the stimuli able to induce the production of chemokines by neutrophils has been previously reported [30], yet agonists triggering neutrophil-derived chemokines are continuously identified, for instance: granulocyte colony-stimulating factor (G-CSF), shown to induce CXCL5 [31] and CXCL2/MIP-2α [32]; Wnt5a, a ligand that activates the non-canonical Wnt signaling pathways (β-catenin-independent pathways), shown to trigger the release of CXCL8 and CCL2 [33]; organic dust, shown to trigger the release of CXCL8 and CCL3 [25]; and an increasing number of microbial-derived products, as described in the following paragraphs.

2.1. Human neutrophils

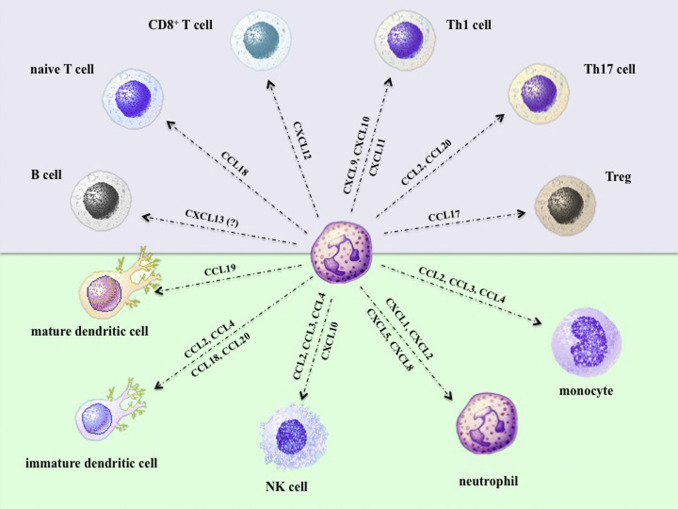

In vitro studies have demonstrated that, upon stimulation with microbial agents or their derivatives, neutrophils release chemokines potentially able to recruit neutrophils themselves, monocytes, macrophages, DCs and NK cells, as well as T cell subsets (Fig. 1 ), suggesting that, by this function, they may amplify both the innate and the adaptive immune response [16]. For example, neutrophils cultured with either Mycobacterium tuberculosis or lipoarabinomann (its major cell wall component) have been shown to release CXCL1 and CXCL8 [34], two chemokines involved in neutrophil recruitment. Similarly, neutrophils release CXCL8 when exposed in vitro to Candida albicans [35], Helicobacter pylori water soluble surface protein [36] and H. pylori neutrophil-activating protein (HP-NAP) [37]. By contrast, phagocytosed Staphylococcus aureus has been shown to reduce the production of CXCL8 by neutrophils, concomitantly with suppressing phosphorylation of nuclear factor-κB and accelerating cell death, in this manner favoring its own survival and promoting disease [38].

Fig. 1.

Chemokines produced/expressed by neutrophils experimentally shown to chemoattract the innate (green background) and adaptive (violet-purple background) immunity cells displayed in the figure.

Further evidence of the role of neutrophil-derived chemokines in amplifying local innate responses has been provided by the capacity of neutrophils to upregulate the expression of CXCL1, CXCL2 and, mostly, CXCL3 when in vitro exposed to Fusobacterium nucleatum [39]. In other studies, neutrophils incubated with LPS- or tumor necrosis factor-α (TNFα) [40], as well as in the presence of Gram-positive or Gram-negative bacteria [41], were shown to sequentially express and release biologically active CCL20 and CCL19 [40], as revealed by experiments in which neutrophil-derived supernatants induced chemotaxis of immature and mature DCs, respectively. These data have been further supported by subsequent findings showing that both IFNγ and the bacterial-derived chemoattractant known as formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine (fMLF) significantly increase the production of neutrophil-derived CCL20 in response to LPS, through entirely unrelated molecular mechanisms [42]. In the case of neutrophils incubated with IFNγ plus LPS, which also maintain very elevated the production of CCL2 [43], a potent antiapoptotic effect exerted by IFNγ likely sustains chemokine expression [43].

As mentioned, neutrophil-derived chemokines may also orchestrate more sophisticated responses involving adaptive immune cells. For example, neutrophils isolated from pulmonary tuberculosis patients were shown to display augmented levels of CXCL8, CCL2 and CCL3, which further increased upon infection with mycobacterial strains in vitro [44]. Consistently, it has been demonstrated that neutrophils exposed to Mycobacterium bovis Bacillus Calmette-Guerin (BCG) [45], or incubated with HP-NAP [37], produce not only CXCL8, but also CCL3 and CCL4, two chemokines recruiting monocytes, DCs and T cells to the site of infections. In support of this notion, supernatants from BCG-conditioned neutrophils were found to induce, in vitro, the chemotaxis of monocytes and, indirectly (via monocytes), of T cells [45]. Neutrophil-derived chemokines have been also involved in regulating the migration of monocytes/macrophages, T cells and neutrophils, which entrap Schistosoma japonicum eggs and ultimately form the typical inflammatory granulomas [46]. Accordingly, human neutrophils exposed in vitro to S. japonicum eggs were found to upregulate the transcripts encoding CCL3, CCL4 and CXCL2 [46], consistent with a previous study from the same group evidencing the presence of CCL3-, CCL4- and CXCL2/MIP-2α-positive neutrophils within the neutrophil-rich core of S. japonicum-granulomas in infected mice [47].

Human neutrophils have been found to synergistically express and release also CXCL9, CXCL10 and express CXCL11 after incubation with IFNγ in combination with either LPS or TNFα [48]. The molecular mechanisms underlying such synergistic effects were subsequently uncovered [49]. Moreover, neutrophil-derived CXCL9 and CXCL10 were found biologically active in vitro, as supernatants harvested from IFNγ plus LPS- or TNFα-treated neutrophils promoted the migration, as well as a rapid integrin-dependent adhesion, of CXCR3-expressing Th1 cells, in CXCL9- or CXCL10-dependent fashions [48]. These observations for the first time have highlighted a potential direct crosstalk between neutrophils and Th1 cells [48], subsequently confirmed and expanded [50], and are important because Th1 cells are crucial for cell-mediated immunity and phagocyte-dependent protective responses [51]. That the production of CXCL9 and CXCL10 by neutrophils might be relevant for fighting infectious diseases was further evidenced by other studies. In one of them, Anaplasma phagocytophilum-infected human neutrophils have been found to release lower amounts of CXCL9 and CXCL10 as compared to uninfected neutrophils [52]. Similarly, Porphyromonas gengivalis was shown to be ineffective in stimulating the release of CXCL10 by neutrophils, therefore contributing to suppress and evading a Th1-immune response in the setting of periodontal disease [53].

In addition to Th1 cells [48], IFNγ plus LPS-activated neutrophils have been shown to produce and release also CCL2 and CCL20, and, in turn, chemoattract Th17 cells in vitro [54]. Th17 cells are specialized in orchestrating adaptive immune defense toward extracellular pathogens, via the recruitment of neutrophils to the site of infection, by triggering the production of CXCL8, CXCL1 and G-CSF from tissue cells [55]. However, Th17 cells are also involved in the pathogenesis of chronic inflammatory and/or autoimmune diseases [56]. Also neutrophils incubated with the neutrophil-activating protein A (NapA) from Borrelia burgdorferi were found to recruit both Th1 and Th17 cells via CXCL10 and CCL2/CCL20 production, respectively [57]. Interestingly, because NapA functions as one of the main bacterial products involved in the pathogenesis of Lyme arthritis, which is characterized by a joint infiltration of mainly neutrophils and T cells (Th1 and Th17), the latter data [57] would suggest that the infiltration of Th cells may rely, in part, on the chemokines locally produced by neutrophils exposed to NapA. That neutrophils and Th17 may undertake a crosstalk, ultimately leading to the amplification of local immune response, is very plausible due to the ability of activated Th17 cells to produce CXCL8 and, consequently, directly attract neutrophils [54].

Much less is known about neutrophil responsiveness to viruses in terms of chemokine production. For instance, it has been reported that neutrophils treated in vitro with the human immunodeficiency virus transactivator protein (Tat) produce CXCL8 [58], while neutrophils incubated with Respiratory Syncytial Virus (RSV) produce and release also CCL3 [59] and CCL4 [60], in addition to CXCL8 [61], therefore disclosing their role as cells releasing potent inflammatory mediators during RSV-related bronchiolitis. Similarly, neutrophils exposed to Herpes Simplex Virus 1 (HSV-1)-infected corneal tissue were found to produce elevated CXCL9 levels [62], suggesting that they contribute to the attraction of CD4+ T cells/Th1 cells, which are essential for antiviral immunity. In pulmonary tuberculosis, neutrophils from the bronco-alveolar lavage fluids (BAL) of patients with human Immunodeficiency Virus (HIV)-associated syndrome have been found to express CXCL10 [63], in spite of a very low number of IFNγ-producing CD4+ cells in BAL. Since CXCL10 is a typical IFNγ-responsive gene, data suggest that HIV might directly or indirectly cause a dysregulated CXCL10 production by human neutrophils [63]. In another study, neutrophils pulse-treated in vitro with R5HIV (a macrophage-tropic HIV strain) have been found to produce CCL2 and IL-10 [64]. Moreover, freshly isolated neutrophils either co-cultured, or transwell-cultured, with R5HIV-infected syngeneic monocyte-derived macrophages were shown to enhance, in a CCL2- and IL-10-dependent manner, the replication of R5HIV in macrophages, thus supporting a neutrophil-mediated role in favoring, at least in vitro, R5HIV infection [64]. In this context, glycyrrhizin, an antiviral compound already used in clinic, was found able to inhibit the in vitro production of CCL2 and IL-10 by neutrophils exposed to R5HIV, therefore providing an example of a potential chemokine/cytokine-targeted therapy [64]. At the light of recent findings demonstrating that, in human neutrophils, the chromatin at the IL-10 locus appears in an inactive conformation [65], the production of IL-10 by R5HIV-treated neutrophils should be confirmed using highly pure neutrophil populations. In another context, neutrophils from Human T cell lymphotropic virus type-1 (HTLV-1)-infected patients exposed in vitro to LPS, or to Leishmania amazonensis, were found to release amounts of CXCL8 and CCL4 similar to neutrophils from HTLV-1-seronegative controls [66]. Finally, neutrophils transfected in vitro with polyinosinic:polycytidylic acid [poly(I:C)], a synthetic mimetic of viral dsRNA that acts via intracellular cytoplasmic RNA helicases, have been shown to express elevated transcript levels encoding CXCL8, CXCL10, CCL4 and CCL20 [67]. Similarly, neutrophils incubated with R848, an imidazoquinoline mimicking the action of single strand viral RNA acting on TLR8, have been shown to express CCL4 [68], as well as CCL3, CCL19, CXCL1, CXCL8 and CXCL16 (our unpublished observations), all chemokines potentially involved in the recruitment of both innate and adaptive immunity cells during viral infections.

2.2. Mouse/rat neutrophils

Evidence that also rodent neutrophils produce chemokines is abundantly documented, as already reviewed [30]. For instance, murine neutrophils exposed in vitro to M. tuberculosis have been shown to produce CXCL2/MIP-2α and CCL3 [69]. In another work, neutrophils have been found to release biologically active CCL3 (e.g., able to chemoattract immature DCs) upon in vitro exposure to Leishmania major [70]. Consistently, neutrophil depletion in L. major-resistant mice was shown to abolish the recruitment of DCs to the site of parasite inoculation, a phenomenon adoptively rescued by inoculation of wild-type neutrophils [70]. Overall, these latter data point to a role for neutrophil-derived CCL3 in the induction of a protective CD4+ Th1 immune response against L. major infection via the recruitment of immature DCs and their subsequent differentiation [71]. In line with the aforementioned model are also results obtained using murine neutrophils exposed in vitro to Toxoplasma gondii, which were found to release many chemokines able to recruit immature DCs (e.g., CCL3, CCL4, CCL5 and CCL20), as experimentally proved [72]. Interestingly, under non-infectious setting, neutrophil-derived CCL3 and CCL4 have been also shown to induce an early macrophage influx to the sites of polyacrylamide gel-induced cutaneous granuloma formation [73].

In another model, namely the methicillin-resistant S. aureus (MRSA) infection, neutrophils from mice resistant to MRSA have been shown to induce, via CCL3 and IL-12 release, the polarization of macrophages towards a phenotype characterized by the expression of cytokines and chemokines potentially associated with a Th1 response (e.g., IFNγ, IL-12, IL-18, CCL3, CCL5, CXCL9 and CXCL10) [74]. By contrast, supernatants of neutrophils obtained from MRSA-susceptible mice [74] were found to polarize macrophages, via the release of CCL2 and IL-10, towards a phenotype characterized by the expression of cytokines and chemokines potentially associated with a Th2 response (e.g., IL-1 receptor antagonist, IL-10, CCL17, CCL18, CCL22) [74]. Similar results were also observed in a model of compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome [75]. Finally, in mice infected with Plasmodium berghei ANKA, neutrophil- and monocyte-derived CXCL10 have been shown to induce the migration of anti-Plasmodium effector cells out of lymphoid secondary organs [76], therefore causing an impaired control of the blood stage of malaria and the consequent entrapment of parasitized red blood cells into the cerebral-microcirculation [76].

As for human neutrophils, increasing evidence point for a role of neutrophil-derived chemokines in organizing immune responses toward viruses also in rodents. For instance, neutrophils isolated from the lungs of influenza virus-infected wild-type mice displayed, in the acute phase, significant levels of CXCL10 mRNA and were also found to express CXCL10 by immunohistochemical (IHC) analysis [77]. By contrast, mice lacking CXCL10 or CXCR3, besides presenting reduced acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) manifestations and an increased survival, had a lower number of infiltrating lung neutrophils as compared to the wild-type strains [77]. Data are consistent with the notion of neutrophil-derived CXCL10 as responsible for the recruitment of additional (CXCR3-positive) neutrophils and the consequent excessive pulmonary inflammation/ARDS [77]. Interestingly, similar data were obtained by inducing a chemical pneumonia using the same models [77]. In a mouse model of influenza A virus infection, neutrophil-derived CXCL12/stromal-cell derived factor 1 (SDF-1) has been instead demonstrated to be crucial for CD8+ T cell recruitment, and therefore for the induction of a CD8+ T cell-mediated immune response towards influenza virus itself [78]. Using two photon microscopy in vivo, mice having CXCL12 conditionally-depleted neutrophils presented fewer T cells within the infection site and had a slower clearance of the virus, similar to the mice with reduced neutrophil counts [78]. Strikingly, the same study has also demonstrated that, during their migration to the site of infection, neutrophils deposit long-lasting, CXCL12-containing trails from their elongated uropods, in this manner guiding T cells towards infected tissue [78]. Finally, rat neutrophils incubated in vitro with conditioned medium from coronavirus (CoV)-infected alveolar epithelial cells have been shown to display higher mRNA levels of CXCL1, CXCL2, CXCL10 and CXCL11, CCL2, CCL4, CCL7, CCL9/mMIP-1γ, CCL12/MCP-5 and CCL22 as compared to neutrophils incubated in a control medium [79]. The potential validity of these in vitro observations in vivo have been confirmed in a rat model of non-fatal lung CoV infection, in which neutrophil-depleted rats displayed fewer macrophages and lymphocytes in their respiratory tract, as compared to non-depleted rats, and lower chemokine levels [79].

3. Neutrophil-derived chemokines in tumors

Increasing experimental evidence indicates that, in addition to macrophages, DCs and lymphocytes, also neutrophils infiltrate tumors [80], to play a role in influencing the neoplastic growth. That occurs not only because tumor-associated neutrophils (TANs) may directly interact with the neoplastic cells, but also because, within the tumor microenvironment, TANs release a wide array of molecules, including chemokines and cytokines [81]. Neutrophil-derived chemokines influence the tumor fate either indirectly, because they recruit and activate innate and adaptive immune cells [81], or directly, for their capacity to modulate angiogenesis and cell proliferation [13], [14]. Recent knowledge on the involvement of neutrophil-derived chemokines exerting pro- or anti-tumoractions is summarized in the following sections.

3.1. Human neutrophils

A number of in vitro studies have demonstrated that peripheral neutrophils may express and/or produce chemokines in the presence of tumor cell-conditioned medium and/or tumor cells. For instance, neutrophils incubated with gastric cancer-derived mesenchymal stem cell-conditioned medium have been shown to upregulate CXCL8 and CCL2 mRNA [82]. CXCL8 was also shown to be produced by neutrophils either co-cultured with metastatic melanoma [83] and glioma cell lines [84], or in the presence of supernatants from a head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) cell line [85]. These observations anticipate a potential role for TANs to regulate in vivo, via CXCL8, not only the recruitment of additional neutrophils, but also cancer cell growth, survival, motion and angiogenesis [86]. Neutrophils incubated in vitro with HNSCC-derived supernatants were also found to release considerable amounts of CCL4 [85], [87], a chemokine that may elicit an immune response towards the tumor by recruiting NK, immature DCs and T cells [87], [88]. In another study, peripheral neutrophils from hepatocellular carcinoma (HCC) patients have been found to produce, in vitro, significantly higher amounts of CCL2 than neutrophils from healthy donors [89]. Moreover, the amounts of neutrophil-derived CCL2 were found to be proportional to the tumor sizes of patients [89]. Consistent with the observations evidencing that mouse neutrophils exerting immunosuppressive functions produce CCL2 and IL-10, while those with immunoactivating properties release CCL3 and IL-12 [74], supernatants from HCC neutrophils were found to inhibit, in vitro, the production of IFNγ by peripheral blood mononuclear cells in a CCL2-dependent fashion [89]. In a more recent study, TANs isolated from HCC samples have been shown to release significant levels of CCL2 and CCL17 in vitro [90], consistent with the capacity of HCC cell lines to induce the production of the same chemokines (CCL2 and CCL17) when co-cultured with neutrophils in vitro [90]. In agreement with the latter data, IHC analysis of human HCC specimens has demonstrated the presence of CCL2- and CCL17-positive TANs within the tumor stroma [90]. Notably, TAN-conditioned media were found to increase, in vitro, the migratory activity of macrophages and T regulatory cells (Tregs) via CCL2 and CCL17, respectively [90], in line with a TAN-N2 protumoral phenotype previously described [80]. An inverse correlation between the number of CCL2- and CCL17-positive TANs in tumor sections and patient survival confirmed the protumor role for TANs in HCC [90]. CCL17 has been found expressed, by flow cytometry, also in TANs from human lung tumors [91], thus suggesting that, also in this type of cancer, TANs may recruit Tregs.

By contrast, TANs isolated from lung tumors of patients at the early stage of disease have been shown to produce significant levels of CXCL8, CCL2 and CCL3, other than IL-6 and the anti-inflammatory IL-1Ra [92]. Although the precise contribution of each chemokine was not specifically addressed, lung tumor TANs were shown to induce, in vitro, the proliferation and the release of IFNγ by both CD4+ and CD8+ T cells [92], pointing for their anti-tumor role. In addition, in vitro experiments uncovered a crosstalk between TANs and activated T cells leading to a substantial upregulation of costimulatory molecules in neutrophils, which, in turn, bolstered a further T cell proliferation in a positive-feedback loop [92]. Similarly to lung TANs [92], human neutrophils infected with an oncolytic vaccine strain of measles virus (MV) have been shown to secrete CXCL8 and CCL2, other than TNFα and IFNα [93]. These observations support and extend previous findings, made in a human tumor xenograft mouse model, demonstrating that neutrophils contribute to the antitumor efficacy of MV, mostly MV expressing granulocyte-macrophage colony-stimulating factor (MV GM-CSF) [94].

3.2. Mouse neutrophils

As a general notion, mouse TANs have been shown to constitutively produce a variety of chemokines, including CXCL1, CXCL2/MIP-2α, CXCL9, CXCL10, CXCL13/B lymphocyte chemoattractant/(BLC), CXCL16, CCL2, CCL3, CCL7 and CCL17 [95], therefore suggesting that they can potentially recruit monocytes/macrophages, DCs, NK cells, T and B cell subsets and/or more neutrophils to the tumor. In turn, the type of immune response elicited by TANs would depend on the pattern of chemokines prevalently produced in each single situation. For instance, TANs isolated from lung tumors were found to express and release higher CCL17 levels than bone marrow neutrophils from the same animals [91]. In this model, TAN-derived supernatants have been shown to preferentially attract Tregs in a CCL17-dependent manner, in migration assays both in vitro and in vivo [91]. Interestingly, TANs isolated from the same mouse model, but after treatment with the transforming growth factor-β (TGF-β)-inhibitor SM16, expressed and released significantly lower amounts of CCL17 than TANs from untreated mice [91], confirming a role for TGF-β in conditioning neutrophil activities towards tumors [96]. In such regard, the presence/absence of TGF-β within the tumor microenvironment has been shown to polarize TANs into two phenotypes displaying opposite immunoregulatory functions, mainly based on their cytokine/chemokine-producing repertoire [97]: in the case of chemokines, CCL3 for the antitumor (N1), CCL2 plus CCL17 for the protumor (N2), phenotype [95], [96]. In agreement with the N1/N2 hypothesis, tumor volume, as well as the number of pulmonary metastases, were shown to significantly increase in a mouse tumor model obtained by coinjecting animals with HCC cell lines together with CCL2 and CCL17-producing TANs. Moreover, these tumors displayed an increased number of stromal macrophages and Tregs [90].

Protumor, proinflammatory activities by infiltrating neutrophils have been also uncovered in another mouse model of colitis-associated cancer, in which prostaglandin receptor (subtype EP2)-positive colon neutrophils were found to express, by IHC, CXCL1 in addition to IL-6, TNFα and COX-2 [98]. Consistent with these findings, bone marrow-derived neutrophils from the same mice were shown to upregulate the expression of CXCL1, TNFα, IL-6 and COX-2 mRNA when incubated with prostaglandin E2 (PGE2) and TNFα in vitro [98]. This suggests that the PGE2-prostaglandin receptor-(EP2) pathway forms an autocrine loop for neutrophil recruitment to the colon by inducing CXCL1 and consequently by amplifying the pro-tumor inflammatory response [98]. Notably, under the same experimental setting (e.g., induced colitis-associated cancer) EP2-deficient mice displayed a reduced number of tumor lesions, therefore pointing for a role for neutrophils in promoting tumorigenesis [98]. Notably, clinical specimens of ulcerative colitis-associated colorectal cancer display EP2-positive infiltrating neutrophils, confirming the findings in mice [98].

4. Neutrophil-derived chemokines in immune-mediated diseases

Immune-mediated inflammatory diseases are a group of diseases lacking a definite etiology and characterized by prolonged inflammatory symptoms, often triggered by a dysregulation of the normal immune response [99]. In addition to other leukocytes, neutrophils have been often shown to be involved in the pathogenesis of these diseases [100].

4.1. Human neutrophils

Evidence points for the involvement of neutrophil-derived chemokines in various types of arthritis. For example, peripheral neutrophils have been shown to release CXCL8 upon phagocytosis of monosodium urate (MSU) crystals in vitro [101]. MSU crystals cause the typical gout attacks when deposit in joints, tendons and surrounding tissues, to which neutrophils participate via the release of proinflammatory mediators [102]. Therefore, because of the capacity of CXCL8 to potently attract neutrophils, these findings would uncover a potential mechanism that may sustain neutrophil-mediated inflammation in gouty arthritis. Neutrophils isolated from the synovial fluid (SF) of patients with rheumatoid arthritis (RA), a systemic autoimmune inflammatory disorder primarily involving the joints, have been shown to produce high levels of CXCL8, CXCL10, CCL2 and CCL20 [54], in addition to express elevated transcript levels of CCL18 and CCL3 [103]. Data would suggest that, in RA arthritis, neutrophils recruit additional neutrophils, as well as Th1 cells and Th17 cells, to undertake reciprocal crosstalk [54]. Consistent with this hypothesis, neutrophils and Th17 cells have been found to closely colocalize in SFs from RA patients [54]. In addition, in vitro experiments have demonstrated that supernatants from IFNγ plus LPS-activated neutrophils induce chemotaxis of Th1 and Th17 cells via CCL2 and CXCL10, and CCL2 and CCL20, respectively [54]. In the same studies, Th17, but not Th1, cells have been shown to release CXCL8 and chemoattract neutrophils in vitro, pointing for their direct action in recruiting neutrophils and therefore in amplifying the local inflammatory response [54]. Interestingly, previous studies had also demonstrated that neutrophils from SFs of RA patients may express CCL20 mRNA and that stimulation with SFs, containing or not TNFα, induced CCL20 mRNA in peripheral neutrophils [104].

Neutrophil-derived chemokines have been suspected to be involved in other immune-mediated diseases, such as ulcerative colitis (UC), an inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) characterized by relapsing mucosal inflammation. Accordingly, in bowel specimens from UC patients, neutrophils have been found to express CXCL1 and CXCL9 by IHC [105], consistent with a role of neutrophil-derived CXCL1 and CXCL9 in recruiting neutrophils, NK and T cells, which are known to be involved in the immunological response causing lesions. Similarly, tissue specimens from another IBD, namely Crohn’s disease (an immune-mediated ileitis), displayed a colocalization of neutrophils and Th17 cells by confocal microscopy [54]. These findings are, once again, supporting neutrophil-derived CCL2 and CCL20 in the pathogenesis of Crohn’s disease via Th17 cells recruitment. Finally, in vitro experiments have shown that, upon stimulation with anti-phospholipid antibodies plus low concentrations of LPS, neutrophils release CXCL8 [106]. It is therefore conceivable to hypothesize a participation of CXCL8 in the pathogenesis of the anti-phospholipid syndrome, a systemic autoimmune disease likely triggered by TLRs activation and characterized by the occurrence of anti-phospholipid antibodies, recurrent thrombosis and fetal loss [106].

4.2. Mouse neutrophils

Fulminant hepatitis develops in about 1% of patients with acute hepatitis B, in whom an excessive host defensive immune response is detected [107]. In such regard, a mouse model of the human disease has been developed, based on an adoptive transfer of antigen-specific cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs) into hepatitis B virus (HBV)-transgenic mice, which, in turn, triggers a fulminant hepatitis [108]. In such a model, injection of antigen-specific cytotoxic T cells in HBV transgenic mice is followed by the recruitment of mononuclear cells and neutrophils into the liver [108]. In this organ, CTLs release IFNγ and TNFα upon antigen recognition, in turn inducing liver neutrophils to release elastase and to upregulate CCL3, CCL4 and CXCL1 mRNA [108]. Importantly, mice treated with anti-CCL3, −CCL4, and −CXCL1 antibodies were found to display a lower recruitment of inflammatory cells into the liver and a reduced hepatic injury, indicating that these neutrophil-derived chemokines mediate the inflammatory and immunological response engaged by CTLs against the HBV-infected hepatocytes [108]. In a model of delayed-type hypersensibility (DTH) obtained by sensitizing mice with Herpes Simplex Virus type I (HSV-1) antigen on the scarified cornea, neutrophils have been demonstrated to recruit T cells by producing CXCL9 and CXCL10 [109]. Consistently, neutrophil depletion was accompanied by a marked decrease in the number of CD4+ T cells to the site of DTH and a drop in the levels of CXCL9 and CXCL10 in DTH tissue lysate [109]. Moreover, consistent with the release of CXCL9 and CXCL10 by neutrophils stimulated in vitro with IFNγ, IFNγ-knockout mice manifested a depressed DTH upon HSV-1 antigen challenge, and only the reconstitution of these mice with IFNγ re-induced the synthesis of both chemokines [109]. Therefore, according to the model described above, neutrophils activated by IFNγ release CXCL9 and CXCL10 and recruit CD4+ T cells. The latter cells, in turn, would contribute to a further production of IFNγ and therefore to the amplification of the inflammatory cascade in sites of DTH [109]. Finally, in a mouse model of cutaneous type III hypersensitivity obtained by injecting antibodies into mouse ear skin, and by systemically delivering the corresponding antigens, immune complexes (ICs)-laden neutrophils isolated from the ears displayed a significantly upregulated expression of CXCL2/MIP-2α as compared to bone-marrow neutrophils [110]. In vitro studies confirmed that the direct stimulation of isolated bone marrow-derived neutrophils with IC triggers a substantial secretion of CXCL2/MIP-2α [110]. Therefore, a role of CXCL2/MIP-2α in recruiting additional neutrophils and endogenously activating their effector functions, including reactive oxygen species production and phagocytosis, might be plausible [110].

5. Conclusions

There is no doubt that neutrophils may regulate leukocyte trafficking during immune responses. As briefly outlined in this short review, this function relies on the neutrophil capacity to produce a variety of chemokines, but it should be not forgotten that also preformed factors contained in neutrophil granules have been shown to be chemotactic for mononuclear cells and neutrophils (for a review, please see reference [111]). Nonetheless, in spite of the large body of data describing the expression pattern of neutrophil-derived chemokines in vitro, we need to expand our knowledge on what is the real significance of this phenomenon in vivo, particularly in humans. Of utmost importance is to improve the techniques to isolate neutrophils from tissues and lymphoid organs (e.g., spleen and lymph-nodes) at very high levels of purity, to avoid false positive data caused by eventual contamination with other cell types. Studies aimed at gaining more insights on the molecular regulation of chemokine expression in neutrophils are also awaited. In fact, similarly to other leukocytes, chemokine expression in neutrophils can be controlled at the transcriptional and/or post-transcriptional level [30], in some cases by sophisticated and cell-specific regulatory mechanisms, including the involvement of microRNAs [69], specific transcription factors [112] and chromatin modifications [65]. However, very little is still known on all these phenomena. Furthermore, neutrophil-derived chemokines can be involved either in physiological and pathological angiogenesis, a function that is often underestimated [13]. Finally, it is known that neutrophils may be engaged into complex bidirectional interactions with other leukocytes or tissue cells [21]. As a result of this crosstalk, neutrophils and target cells reciprocally modulate their survival and activation status. Chemokines might certainly contribute to regulate such a crosstalk, but their effective roles remains mostly unsolved. In such regard, future challenges for scientists in the field will be to translate all this knowledge into efficacious neutrophil-targeted therapies without compromising immunity.

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare no financial or commercial conflict of interest.

Acknowledgments

M.A.C. is supported by a grant from Associazione Italiana per la Ricerca sul Cancro (AIRC, IG-15454). CT is supported by a grant from Alessandro Moretti Foundation, Lions Club (San Giovanni Lupatoto, Zevio e destra Adige, Verona).

We apologize for not having discussed all the papers published in the field due to restricted length limitations.

Contributor Information

Cristina Tecchio, Email: cristina.tecchio@univr.it.

Marco A. Cassatella, Email: marco.cassatella@univr.it.

References

- 1.Sokol C.L., Luster A.D. The chemokine system in innate immunity. Cold Spring Harbor Perspect. Biol. 2015;7(January (5)) doi: 10.1101/cshperspect.a016303. (pii: a016303) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Strieter R.M., Polverini P.J., Kunkel S.L., Arenberg D.A., Burdick M.D., Kasper J., Dzuiba J., Van Damme J., Walz A., Marriott D. The functional role of the ELR motif in CXC chemokine-mediated angiogenesis. J. Biol. Chem. 1995;270:27348–27357. doi: 10.1074/jbc.270.45.27348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oppenheim J.J., Zachariae C.O., Mukaida N., Matsushima K. Properties of the novel proinflammatory supergene intercrine cytokine family. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 1991;9:617–648. doi: 10.1146/annurev.iy.09.040191.003153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Baggiolini M., Dewald B., Moser B. Interleukin-8 and related chemotactic cytokines–CXC and CC chemokines. Adv. Immunol. 1994;55:97–179. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Farber J.M. Mig and IP-10: CXC chemokines that target lymphocytes. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1997;61:246–257. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cole K.E., Strick C.A., Paradis T.J., Ogborne K.T., Loetscher M., Gladue R.P., Lin W., Boyd J.G., Moser B., Wood D.E., Sahagan B.G., Neote K. Interferon-inducible T cell alpha chemoattractant (I-tAC): a novel non-eLR CXC chemokine with potent activity on activated T cells through selective high affinity binding to CXCR3. J. Exp. Med. 1998;187:2009–2021. doi: 10.1084/jem.187.12.2009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Rollins B.J. Chemokines. Blood. 1997;90:909–928. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Murphy P.M. International Union of Pharmacology: XXX. Update on chemokine receptor nomenclature. Pharmacol. Rev. 2002;54:227–229. doi: 10.1124/pr.54.2.227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rossi D., Zlotnik A. The biology of chemokines and their receptors. Annu. Rev. Immunol. 2000;18:217–242. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.18.1.217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zlotnik A., Yoshie O. The chemokine superfamily revisited. Immunity. 2012;36:705–716. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2012.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mantovani A. Chemokines: introduction and overview. Chem. Immunol. 1999;72:1–6. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ward S.G., Bacon K., Westwick J. Chemokines and T lymphocytes: more than an attraction. Immunity. 1998;9:1–11. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80583-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tecchio C., Cassatella M.A. Neutrophil-derived cytokines involved in physiological and pathological angiogenesis. Chem. Immunol. Allergy. 2014;99:123–137. doi: 10.1159/000353358. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tazzyman S., Niaz H., Murdoch C. Neutrophil-mediated tumour angiogenesis: subversion of immune responses to promote tumour growth. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2013;23:149–158. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.02.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Chow M.T., Luster A.D. Chemokines in cancer. Cancer Immunol. Res. 2014;2:1125–1131. doi: 10.1158/2326-6066.CIR-14-0160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Scapini P., Lapinet-Vera J.A., Gasperini S., Calzetti F., Bazzoni F., Cassatella M.A. The neutrophil as a cellular source of chemokines. Immunol. Rev. 2000;177:195–203. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.17706.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Luster A.D. Chemokines–chemotactic cytokines that mediate inflammation. N. Engl. J. Med. 1998;338:436–445. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199802123380706. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hosking M.P., Lane T.E. The role of chemokines during viral infection of the CNS. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000937. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Iannello A., Thompson T.W., Ardolino M., Lowe S.W., Raulet D.H. p53-Dependent chemokine production by senescent tumor cells supports NKG2D-dependent tumor elimination by natural killer cells. J. Exp. Med. 2013;210:2057–2069. doi: 10.1084/jem.20130783. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mócsai A. Diverse novel functions of neutrophils in immunity, inflammation, and beyond. J. Exp. Med. 2013;210:1283–1299. doi: 10.1084/jem.20122220. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Scapini P., Cassatella M.A. Social networking of human neutrophils within the immune system. Blood. 2014;124:710–719. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-03-453217. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tecchio C., Micheletti A., Cassatella M.A. Neutrophil-derived cytokines: facts beyond expression. Front. Immunol. 2014;5:508. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2014.00508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.SadikC.D. Kim N.D., Luster A.D. Neutrophils cascading their way to inflammation. Trends Immunol. 2011;32:452–460. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2011.06.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cassatella M.A. The production of cytokines by polymorphonuclear neutrophils. Immunol. Today. 1995;16:21–26. doi: 10.1016/0167-5699(95)80066-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Blidberg K., Palmberg L., Dahlén B., Lantz A.S., Larsson K. Chemokine release by neutrophils in chronic obstructive pulmonary disease. Innate Immun. 2012;18:503–510. doi: 10.1177/1753425911423270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schauer C., Janko C., Munoz L.E., Zhao Y., Kienhöfer D., Frey B., Lell M., Manger B., Rech J., Naschberger E., Holmdahl R., Krenn V., Harrer T., Jeremic I., Bilyy R., Schett G., Hoffmann M., Herrmann M. Aggregated neutrophil extracellular traps limit inflammation by degrading cytokines and chemokines. Nat. Med. 2014;20:511–517. doi: 10.1038/nm.3547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wittamer V., Bondue B., Guillabert A., Vassart G., Parmentier M., Communi D. Neutrophil-mediated maturation of chemerin: a link between innate and adaptive immunity. J. Immunol. 2005;175:487–493. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.175.1.487. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kobayashi Y. The role of chemokines in neutrophil biology. Front. Biosci. 2008;13:2400–2407. doi: 10.2741/2853. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wright H.L., Moots R.J., Edwards S.W. The multifactorial role of neutrophils in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat Rev. Rheumatol. 2014;10:593–601. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cassatella M.A. Neutrophil-derived proteins: selling cytokines by the pound. Adv. Immunol. 1999;73:369–509. doi: 10.1016/s0065-2776(08)60791-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Suzuki S., Kobayashi M., Chiba K., Horiuchi I., Wang J., Kondoh T., Hashino S., Tanaka J., Hosokawa M., Asaka M. Autocrine production of epithelial cell-derived neutrophil attractant-78 induced by granulocyte colony-stimulating factor in neutrophils. Blood. 2002;99:1863–1865. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Nguyen-Jackson H.T., Li H.S., Zhang H., Ohashi E., Watowich S.S. G-CSF-activated STAT3 enhances production of the chemokine MIP-2 in bone marrow neutrophils. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2012;92:1215–1225. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0312126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jung Y.S., Lee H.Y., Kim S.D., Park J.S., Kim J.K., Suh P.G., Bae Y.S. Wnt5a stimulates chemotactic migration and chemokine production in human neutrophils. Exp. Mol. Med. 2013;45:e27. doi: 10.1038/emm.2013.48. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Riedel D.D., Kaufmann S.H. Chemokine secretion by human polymorphonuclear granulocytes after stimulation with Mycobacterium tuberculosis and lipoarabinomannan. Infect. Immun. 1997;65:4620–4623. doi: 10.1128/iai.65.11.4620-4623.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Gasparoto T.H., de Oliveira C.E., Vieira N.A., Porto V.C., Cunha F.Q., Garlet G.P., Campanelli A.P., Lara V.S. Activation pattern of neutrophils from blood of elderly individuals with Candida-related denture stomatitis. Eur. J. Clin. Microbiol. Infect. Dis. 2012;31:1271–1277. doi: 10.1007/s10096-011-1439-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Shimoyama T., Fukuda S., Liu Q., Nakaji S., Fukuda Y., Sugawara K. Helicobacter pylori water soluble surface proteins prime human neutrophils for enhanced production of reactive oxygen species and stimulate chemokine production. J. Clin. Pathol. 2003;56:348–351. doi: 10.1136/jcp.56.5.348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Polenghi A., Bossi F., Fischetti F., Durigutto P., Cabrelle A., Tamassia N., Cassatella M.A., Montecucco C., Tedesco F., de Bernard M. The neutrophil-activating protein of Helicobacter pylori crosses endothelia to promote neutrophil adhesion in vivo. J. Immunol. 2007;178:1312–1320. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.178.3.1312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Zurek O.W., Pallister K.B., Voyich J.M. Staphylococcus aureus inhibits neutrophil-derived IL-8 to promote cell death. J. Infect. Dis. 2015;212:934–938. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiv124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wright H.J., Chapple I.L., Matthews J.B., Cooper P.R. Fusobacterium nucleatum regulation of neutrophil transcription. J. Periodontal Res. 2011;46:1–12. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0765.2010.01299.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Scapini P., Laudanna C., Pinardi C., Allavena P., Mantovani A., Sozzani S., Cassatella M.A. Neutrophils produce biologically active macrophage inflammatory protein-3alpha (MIP-3alpha)/CCL20 and MIP-3beta/CCL19. Eur. J. Immunol. 2001;31:1981–1988. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200107)31:7<1981::aid-immu1981>3.0.co;2-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Akahoshi T., Sasahara T., Namai R., Matsui T., Watabe H., Kitasato H., Inoue M., Kondo H. Production of macrophage inflammatory protein 3alpha (MIP-3alpha) (CCL20) and MIP-3beta (CCL19) by human peripheral blood neutrophils in response to microbial pathogens. Infect. Immun. 2003;71:524–526. doi: 10.1128/IAI.71.1.524-526.2003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Scapini P., Crepaldi L., Pinardi C., Calzetti F., Cassatella M.A. CCL20/macrophage inflammatory protein-3alpha production in LPS-stimulated neutrophils is enhanced by the chemoattractant formyl-methionyl-leucyl-phenylalanine and IFN-gamma through independent mechanisms. Eur. J. Immunol. 2002;32:3515–3524. doi: 10.1002/1521-4141(200212)32:12<3515::AID-IMMU3515>3.0.CO;2-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Yoshimura T., Takahashi M. IFN-gamma-mediated survival enables human neutrophils to produce MCP-1/CCL2 in response to activation by TLR ligands. J. Immunol. 2007;179:1942–1949. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.179.3.1942. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hilda J.N., Narasimhan M., Das S.D. Neutrophils from pulmonary tuberculosis patients show augmented levels of chemokines MIP-1α, IL-8 and MCP-1 which further increase upon in vitro infection with mycobacterial strains. Hum. Immunol. 2014;75:914–922. doi: 10.1016/j.humimm.2014.06.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Suttmann H., Riemensberger J., Bentien G., Schmaltz D., Stöckle M., Jocham D., Böhle A., Brandau S. Neutrophil granulocytes are required for effective Bacillus Calmette-Guérin immunotherapy of bladder cancer and orchestrate local immune responses. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8250–8257. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-06-1416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Chuah C., Jones M.K., Burke M.L., McManus D.P., Owen H.C., Gobert G.N. Defining a pro-inflammatory neutrophil phenotype in response to schistosome eggs. Cell. Microbiol. 2014;16:1666–1677. doi: 10.1111/cmi.12316. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Chuah C., Jones M.K., Burke M.L., Owen H.C., Anthony B.J., McManus D.P., Ramm G.A., Gobert G.N. Spatial and temporal transcriptomics of Schistosoma japonicum-induced hepatic granuloma formation reveals novel roles for neutrophils. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2013;94:353–365. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1212653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gasperini S., Marchi M., Calzetti F., Laudanna C., Vicentini L., Olsen H., Murphy M., Liao F., Farber J., Cassatella M.A. Gene expression and production of the monokine induced by IFN-gamma (MIG), IFN-inducible T cell alpha chemoattractant (I-TAC), and IFN-gamma-inducible protein-10 (IP-10) chemokines by human neutrophils. J. Immunol. 1999;162:4928–4937. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Tamassia N., Calzetti F., Ear T., Cloutier A., Gasperini S., Bazzoni F., McDonald P.P., Cassatella M.A. Molecular mechanisms underlying the synergistic induction of CXCL10 by LPS and IFN-gamma in human neutrophils. Eur. J. Immunol. 2007;37:2627–2634. doi: 10.1002/eji.200737340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Jaillon S., Galdiero M.R., Del Prete D., Cassatella M.A., Garlanda C., Mantovani A. Neutrophils in innate and adaptive immunity. Semin. Immunopathol. 2013;35:377–394. doi: 10.1007/s00281-013-0374-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Del Prete G., Maggi E., Romagnani S. Human Th1 and Th2 cells: functional properties, mechanisms of regulation, and role in disease. Lab. Invest. 1994;70:299–306. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bussmeyer U., Sarkar A., Broszat K., Lüdemann T., Möller S., van Zandbergen G., Bogdan C., Behnen M., Dumler J.S., von Loewenich F.D., Solbach W., Laskay T. Impairment of gamma interferon signaling in human neutrophils infected with Anaplasma phagocytophilum. Infect. Immun. 2010;78:358–363. doi: 10.1128/IAI.01005-09. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Jauregui C.E., Wang Q., Wright C.J., Takeuchi H., Uriarte S.M., Lamont R.J. Suppression of T-cell chemokines by Porphyromonas gingivalis. Infect. Immun. 2013;81:2288–2295. doi: 10.1128/IAI.00264-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Pelletier M., Maggi L., Micheletti A., Lazzeri E., Tamassia N., Costantini C., Cosmi L., Lunardi C., Annunziato F., Romagnani S., Cassatella M.A. Evidence for a cross-talk between human neutrophils and Th17 cells. Blood. 2010;115:335–343. doi: 10.1182/blood-2009-04-216085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Annunziato F., Romagnani C., Romagnani S. The 3 major types of innate and adaptive cell-mediated effector immunity. J. Allergy Clin. Immunol. 2015;135:626–635. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.11.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Burkett P.R., Meyer zu Horste G., Kuchroo V.K. Pouring fuel on the fire: Th17 cells, the environment, and autoimmunity. J. Clin. Invest. 2015;125:2211–2219. doi: 10.1172/JCI78085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Codolo G., Bossi F., Durigutto P., Bella C.D., Fischetti F., Amedei A., Tedesco F., D'Elios S., Cimmino M., Micheletti A., Cassatella M.A., D'Elios M.M., de Bernard M. Orchestration of inflammation and adaptive immunity in Borrelia burgdorferi-induced arthritis by neutrophil-activating protein A. Arthritis Rheum. 2013;65:1232–1242. doi: 10.1002/art.37875. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Benelli R., Barbero A., Ferrini S., Scapini P., Cassatella M., Bussolino F., Tacchetti C., Noonan D.M., Albini A. Human immunodeficiency virus transactivator protein (Tat) stimulates chemotaxis, calcium mobilization, and activation of human polymorphonuclear leukocytes: implications for Tat-mediated pathogenesis. J. Infect. Dis. 2000;182:1643–1651. doi: 10.1086/317597. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.König B., Krusat T., Streckert H.J., König W. IL-8 release from human neutrophils by the respiratory syncytial virus is independent of viral replication. J. Leukoc. Biol. 1996;60:253–260. doi: 10.1002/jlb.60.2.253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Jaovisidha P., Peeples M.E., Brees A.A., Carpenter L.R., Moy J.N. Respiratory syncytial virus stimulates neutrophil degranulation and chemokine release. J. Immunol. 1999;163:2816–2820. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Tang F.S., Van Ly D., Spann K., Reading P.C., Burgess J.K., Hartl D., Baines K.J., Oliver B.G. Differential neutrophil activation in viral infections: enhanced TLR-7/8-mediated CXCL8 release in asthma. Respirology. 2016;21:172–179. doi: 10.1111/resp.12657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Molesworth-Kenyon S.J., Milam A., Rockette A., Troupe A., Oakes J.E., Lausch R.N. Expression, inducers and cellular sources of the chemokine MIG (CXCL 9), during primary herpes simplex virus type-1 infection of the cornea. Curr. Eye Res. 2015;40:800–808. doi: 10.3109/02713683.2014.957779. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Kibiki G.S., Myers L.C., Kalambo C.F., Hoang S.B., Stoler M.H., Stroup S.E., Houpt E.R. Bronchoalveolar neutrophils, interferon gamma-inducible protein 10 and interleukin-7 in AIDS-associated tuberculosis. Clin. Exp. Immunol. 2007;148:254–259. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2249.2007.03330.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Yoshida T., Kobayashi M., Li X.D., Pollard R.B., Suzuki F. Inhibitory effect of glycyrrhizin on the neutrophil-dependent increase of R5HIV replication in cultures of macrophages. Immunol. Cell Biol. 2009;87:554–558. doi: 10.1038/icb.2009.40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Tamassia N., Zimmermann M., Castellucci M., Ostuni R., Bruderek K., Schilling B., Brandau S., Bazzoni F., Natoli G., Cassatella M.A. Cutting edge: an inactive chromatin configuration at the IL-10 locus in human neutrophils. J. Immunol. 2013;190:1921–1925. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1203022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Bezerra C.A., Cardoso T.M., Giudice A., Porto A.F., Santos S.B., Carvalho E.M., Bacellar O. Evaluation of the microbicidal activity and cytokines/chemokines profile released by neutrophils from HTLV-1-infected individuals. Scand. J. Immunol. 2011;74:310–317. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3083.2011.02579.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Tamassia N., Le Moigne V., Rossato M., Donini M., McCartney S., Calzetti F., Colonna M., Bazzoni F., Cassatella M.A. Activation of an immunoregulatory and antiviral gene expression program in poly(I:C)-transfected human neutrophils. J. Immunol. 2008;181:6563–6573. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.181.9.6563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Zimmermann M., Aguilera F.B., Castellucci M., Rossato M., Costa S., Lunardi C., Ostuni R., Girolomoni G., Natoli G., Bazzoni F., Tamassia N., Cassatella M.A. Chromatin remodelling and autocrine TNFα are required for optimal interleukin-6 expression in activated human neutrophils. Nat. Commun. 2015;6:6061. doi: 10.1038/ncomms7061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Dorhoi A., Iannacone M., Farinacci M., Faé K.C., Schreiber J., Moura-Alves P., Nouailles G., Mollenkopf H.J., Oberbeck-Müller D., Jörg S., Heinemann E., Hahnke K., Löwe D., Del Nonno F., Goletti D., Capparelli R., Kaufmann S.H. MicroRNA-223 controls susceptibility to tuberculosis by regulating lung neutrophil recruitment. J. Clin. Invest. 2013;123:4836–4848. doi: 10.1172/JCI67604. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Charmoy M., Brunner-Agten S., Aebischer D., Auderset F., Launois P., Milon G., Proudfoot A.E., Tacchini-Cottier F. Neutrophil-derived CCL3 is essential for the rapid recruitment of dendritic cells to the site of Leishmania major inoculation in resistant mice. PLoS Pathog. 2010;6:e1000755. doi: 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000755. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.León B., López-Bravo M., Ardavín C. Monocyte-derived dendritic cells formed at the infection site control the induction of protective T helper 1 responses against Leishmania. Immunity. 2007;26:519–531. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2007.01.017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Bennouna S., Bliss S.K., Curiel T.J., Denkers E.Y. Cross-talk in the innate immune system: neutrophils instruct recruitment and activation of dendritic cells during microbial infection. J. Immunol. 2003;171:6052–6058. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.171.11.6052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.von Stebut E., Metz M., Milon G., Knop J., Maurer M. Early macrophage influx to sites of cutaneous granuloma formation is dependent on MIP-1alpha/beta released from neutrophils recruited by mast cell-derived TNFalpha. Blood. 2003;101:210–215. doi: 10.1182/blood-2002-03-0921. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Tsuda Y., Takahashi H., Kobayashi M., Hanafusa T., Herndon D.N., Suzuki F. Three different neutrophil subsets exhibited in mice with different susceptibilities to infection by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Immunity. 2004;21:215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Takahashi H., Tsuda Y., Kobayashi M., Herndon D.N., Suzuki F. CCL2 as a trigger of manifestations of compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome in mice with severe systemic inflammatory response syndrome. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2006;79:789–796. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0705372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Ioannidis L.J., Nie C.Q., Ly A., Ryg-Cornejo V., Chiu C.Y., Hansen D.S. Monocyte- and neutrophil-derived CXCL10 impairs efficient control of blood-stage malaria infection and promotes severe disease. J. Immunol. 2016;196:1227–1238. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1501562. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Ichikawa A., Kuba K., Morita M., Chida S., Tezuka H., Hara H., Sasaki T., Ohteki T., Ranieri V.M., dos Santos C.C., Kawaoka Y., Akira S., Luster A.D., Lu B., Penninger J.M., Uhlig S., Slutsky A.S., Imai Y. CXCL10-CXCR3 enhances the development of neutrophil-mediated fulminant lung injury of viral and nonviral origin. Am. J. Respir. Crit. Care Med. 2013;187:65–77. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201203-0508OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Lim K., Hyun Y.M., Lambert-Emo K., Capece T., Bae S., Miller R., Topham D.J., Kim M. Neutrophil trails guide influenza-specific CD8+ T cells in the airways. Science. 2015;349(6252):aaa4352. doi: 10.1126/science.aaa4352. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Haick A.K., Rzepka J.P., Brandon E., Balemba O.B., Miura T.A. Neutrophils are needed for an effective immune response against pulmonary rat coronavirus infection, but also contribute to pathology. J. Gen. Virol. 2014;95(Pt 3):578–590. doi: 10.1099/vir.0.061986-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Fridlender Z.G., Albelda S.M. Tumor-associated neutrophils: friend or foe. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33:949–955. doi: 10.1093/carcin/bgs123. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Tecchio C., Scapini P., Pizzolo G., Cassatella M.A. On the cytokines produced by human neutrophils in tumors. Semin. Cancer Biol. 2013;23:159–170. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2013.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Zhu Q., Zhang X., Zhang L., Li W., Wu H., Yuan X., Mao F., Wang M., Zhu W., Qian H., Xu W. The IL-6-STAT3 axis mediates a reciprocal crosstalk between cancer-derived mesenchymal stem cells and neutrophils to synergistically prompt gastric cancer progression. Cell Death Dis. 2014;19(5):e1295. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2014.263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Peng H.H., Liang S., Henderson A.J., Dong C. Regulation of interleukin-8 expression in melanoma stimulated neutrophil inflammatory response. Exp. Cell Res. 2007;313:551–559. doi: 10.1016/j.yexcr.2006.10.030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Hor W.S., Huang W.L., Lin Y.S., Yang B.C. Cross-talk between tumor cells and neutrophils through the Fas (APO-1, CD95)/FasL system: human glioma cells enhance cell viability and stimulate cytokine production in neutrophils. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2003;73:363–368. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0702375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dumitru C.A., Fechner M.K., Hoffmann T.K., Lang S., Brandau S. A novel p38-MAPK signaling axis modulates neutrophil biology in head and neck cancer. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2012;91:591–598. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0411193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Yuan A., Chen J.J., Yao P.L., Yang P.C. The role of interleukin-8 in cancer cells and microenvironment interaction. Front. Biosci. 2005;10:853–865. doi: 10.2741/1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Trellakis S., Bruderek K., Dumitru C.A., Gholaman H., Gu X., Bankfalvi A., Scherag A., Hütte J., Dominas N., Lehnerdt G.F., Hoffmann T.K., Lang S., Brandau S. Polymorphonuclear granulocytes in human head and neck cancer: enhanced inflammatory activity, modulation by cancer cells and expansion in advanced disease. Int. J. Cancer. 2011;129:2183–2193. doi: 10.1002/ijc.25892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Chiba K., Zhao W., Chen J., Wang J., Cui H.Y., Kawakami H., Miseki T., Satoshi H., Tanaka J., Asaka M., Kobayashi M. Neutrophils secrete MIP-1 beta after adhesion to laminin contained in basement membrane of blood vessels. Br. J. Haematol. 2004;127:592–597. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2141.2004.05242.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Tsuda Y., Fukui H., Asai A., Fukunishi S., Miyaji K., Fujiwara S., Teramura K., Fukuda A., Higuchi K. An immunosuppressive subtype of neutrophils identified in patients with hepatocellular carcinoma. J. Clin. Biochem. Nutr. 2012;51:204–212. doi: 10.3164/jcbn.12-32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Zhou S.L., Zhou Z.J., Hu Z.Q., Huang X.W., Wang Z., Chen E.B., Fan J., Cao Y., Dai Z., Zhou J. Tumor-associated neutrophils recruit macrophages and T-regulatory cells to promote progression of hepatocellular carcinoma and resistance to sorafenib. Gastroenterology. 2016;16(February):00231–00236. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2016.02.040. pii: S0016-5085 (Epub ahead of print) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Mishalian I., Bayuh R., Eruslanov E., Michaeli J., Levy L., Zolotarov L., Singhal S., Albelda S.M., Granot Z., Fridlender Z.G. Neutrophils recruit regulatory T-cells into tumors via secretion of CCL17–a new mechanism of impaired antitumor immunity. Int. J. Cancer. 2014;135:1178–1186. doi: 10.1002/ijc.28770. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Eruslanov E.B., Bhojnagarwala P.S., Quatromoni J.G., Stephen T.L., Ranganathan A., Deshpande C., Akimova T., Vachani A., Litzky L., Hancock W.W., Conejo-Garcia J.R., Feldman M., Albelda S.M., Singhal S. Tumor-associated neutrophils stimulate T cell responses in early-stage human lung cancer. J. Clin. Invest. 2014;124:5466–5480. doi: 10.1172/JCI77053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Zhang Y., Patel B., Dey A., Ghorani E., Rai L., Elham M., Castleton A.Z., Fielding A.K. Attenuated, oncolytic, but not wild-type measles virus infection has pleiotropic effects on human neutrophil function. J. Immunol. 2012;188:1002–1010. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.1102262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Grote D., Cattaneo R., Fielding A.K. Neutrophils contribute to the measles virus-induced antitumor effect: enhancement by granulocyte macrophage colony-stimulating factor expression. Cancer Res. 2003;63:6463–6468. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Fridlender Z.G., Sun J., Mishalian I., Singhal S., Cheng G., Kapoor V., Horng W., Fridlender G., Bayuh R., Worthen G.S., Albelda S.M. Transcriptomic analysis comparing tumor-associated neutrophils with granulocytic myeloid-derived suppressor cells and normal neutrophils. PLoS One. 2012;7(2):e31524. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031524. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Fridlender Z.G., Sun J., Kim S., Kapoor V., Cheng G., Ling L., Worthen G.S., Albelda S.M. Polarization of tumor-associated neutrophil phenotype by TGF-beta: N1 versus N2 TAN. Cancer Cell. 2009;16:183–194. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2009.06.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Sionov R.V., Fridlender Z.G., Granot Z. The multifaceted roles neutrophils play in the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Microenviron. 2015;8:125–158. doi: 10.1007/s12307-014-0147-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Ma X., Aoki T., Tsuruyama T., Narumiya S. Definition of prostaglandin E2-EP2 signals in the colon tumor microenvironment that amplify inflammation and tumor growth. Cancer Res. 2015;75:2822–2832. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Shurin M.R., Smolkin Y.S., editors. Advances in Experimental Medicine and Biology. Springer; 2007. Immune mediated diseases: from theory to therapy. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Wright H.L., Moots R.J., Edwards S.W. The multifactorial role of neutrophils in rheumatoid arthritis. Nat. Rev. Rheumatol. 2014;10:593–601. doi: 10.1038/nrrheum.2014.80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Gagné V., Marois L., Levesque J.M., Galarneau H., Lahoud M.H., Caminschi I., Naccache P.H., Tessier P., Fernandes M.J. Modulation of monosodium urate crystal-induced responses in neutrophils by the myeloid inhibitory C-type lectin-like receptor: potential therapeutic implications. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2013;15:R73. doi: 10.1186/ar4250. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Schett G., Schauer C., Hoffmann M., Herrmann M. Why does the gout attack stop? A roadmap for the immune pathogenesis of gout. RMD Open. 2015;1(Suppl 1):e000046. doi: 10.1136/rmdopen-2015-000046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Auer J., Bläss M., Schulze-Koops H., Russwurm S., Nagel T., Kalden J.R., Röllinghoff M., Beuscher H.U. Expression and regulation of CCL18 in synovial fluid neutrophils of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. Arthritis Res. Ther. 2007;9(5):R94. doi: 10.1186/ar2294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Schlenk J., Lorenz H.M., Haas J.P., Herrmann M., Hohenberger G., Kalden J.R., Röllinghoff M., Beuscher H.U. Extravasation into synovial tissue induces CCL20 mRNA expression in polymorphonuclear neutrophils of patients with rheumatoid arthritis. J. Rheumatol. 2005;32:2291–2298. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Egesten A., Eliasson M., Olin A.I., Erjefält J.S., Bjartell A., Sangfelt P., Carlson M. The proinflammatory CXC-chemokines GRO-alpha/CXCL1 and MIG/CXCL9 are concomitantly expressed in ulcerative colitis and decrease during treatment with topical corticosteroids. Int. J. Colorectal Dis. 2007;22:1421–1427. doi: 10.1007/s00384-007-0370-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Gladigau G., Haselmayer P., Scharrer I., Munder M., Prinz N., Lackner K., Schild H., Stein P., Radsak M.P. A role for toll-like receptor mediated signals in neutrophils in the pathogenesis of the anti-phospholipid syndrome. PLoS One. 2012;7:e42176. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0042176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Kondo Y., Kobayashi K., Asabe S., Shiina M., Niitsuma H., Ueno Y., Kobayashi T., Shimosegawa T. Vigorous response of cytotoxic T lymphocytes associated with systemic activation of CD8T lymphocytes in fulminant hepatitis B. Liver Int. 2004;24:561–567. doi: 10.1111/j.1478-3231.2004.0982.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Takai S., Kimura K., Nagaki M., Satake S., Kakimi K., Moriwaki H. Blockade of neutrophil elastase attenuates severe liver injury in hepatitis B transgenic mice. J. Virol. 2005;79:15142–15150. doi: 10.1128/JVI.79.24.15142-15150.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Molesworth-Kenyon S.J., Oakes J.E., Lausch R.N. A novel role for neutrophils as a source of T cell-recruiting chemokines IP-10 and Mig during the DTH response to HSV-1 antigen. J. Leukoc. Biol. 2005;77:552–559. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0904485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Li J.L., Lim C.H., Tay F.W., Goh C.C., Devi S., Malleret B., Lee B., Bakocevic N., Chong S.Z., Evrard M., Tanizaki H., Lim H.Y., Russell B., Renia L., Zolezzi F., Poidinger M., Angeli V., St John A.L., Harris J.E., Tey H.L., Tan S.M., Kabashima K., Weninger W., Larbi A., Ng L.G. Neutrophils self-regulate immune complex-mediated cutaneous inflammation through CXCL2. J. Invest. Dermatol. 2016;136:416–424. doi: 10.1038/JID.2015.410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Chertov O., Yang D., Howard O.M., Oppenheim J.J. Leukocyte granule proteins mobilize innate host defenses and adaptive immune responses. Immunol. Rev. 2000;177:68–78. doi: 10.1034/j.1600-065x.2000.17702.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Cloutier A., Guindi C., Larivée P., Dubois C.M., Amrani A., McDonald P.P. Inflammatory cytokine production by human neutrophils involves C/EBP transcription factors. J. Immunol. 2009;182:563–571. doi: 10.4049/jimmunol.182.1.563. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]