Summary

In some nation states, sustained integrated global epidemiological surveillance has been weakened as a result of political unrest, disinterest, and a poorly developed infrastructure due to rapidly increasing global inequality. The emergence of severe acute respiratory syndrome has shown vividly the importance of sensitive worldwide surveillance. The Agency for Cooperation in International Health, a Japanese non-governmental organisation, has developed on a voluntary basis a sentinel surveillance system for selected target infectious diseases, covering South America, Africa, and Asia. The system has uncovered unreported infectious diseases of international importance including cholera, plague, and influenza; current trends of acute flaccid paralysis surveillance in polio eradication; and prevalence of HIV, syphilis, hepatitis B, and hepatitis C in individual areas covered by the sentinels. Despite a limited geographical coverage, the system seems to supplement disease information being obtained by global surveillance. Further development of this sentinel surveillance system would be desirable to contribute to current global surveillance efforts, for which, needless to say, national surveillance and alert system takes principal responsibility.

The role of epidemiological surveillance to identify public-health problems

Epidemiological surveillance is a basic tool for discovering the problem of infectious diseases. It can define the behaviour of disease in populations and on this basis the magnitude of the public-health problem can be assessed and an effective strategy can be developed. The importance of epidemiological surveillance was shown vividly during smallpox eradication. The intensified surveillance in west Africa, for example, as well as the Indian subcontinent in the late 1960s and early 1970s, found that fewer than 10% of cases were at that time reported or known to the health services concerned.1 This discovery resulted in the decision that a mass vaccination campaign without surveillance was ineffective since containment vaccination for the interruption of smallpox transmission had to be guided by effective surveillance activity. Currently in polio eradication, acute flaccid paralysis (APP) surveillance has shown the extent of wild poliovirus transmission in areas where intensive immunisation programmes have been instituted.2 In fact, this strategy has resulted in the stoppage of transmission in the western hemisphere, Europe, and the western Pacific within 10 years from the start of the global programme.

Experience, however, has shown that surveillance does not always function as desired, nor does it lead to effective control action. During smallpox and polio eradication, it was recognised that surveillance often has weaknesses, such as poor population awareness, inadequate health facilities, superstition and beliefs that discourage reporting, conscious or unconscious suppression of reporting, and inadequate diagnostic techniques. Even today these weaknesses occur in surveillance activities for many diseases. The recent epidemic of severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) is a vivid example. Unreported outbreaks of SARS in the southern coastal areas of China in the autumn of 2002, resulted in worldwide spread in 2003. Monkeypox outbreaks in May, 2003, in the USA are perhaps more appropriately classified in the category of inadequate diagnosis, but showed the international community what could happen in the case of the deliberate release of smallpox virus, whose clinical features closely resemble those of smallpox.3

These are examples of the weakness of surveillance in the past and present, but surveillance may have worsened since in recent years the power of national authorities has been declining due to political unrest, wars, terrorism, increasing global inequality, and cross-nation movement of people in regions of low income in Africa, Asia, and South America.

Introduction of a sentinel system

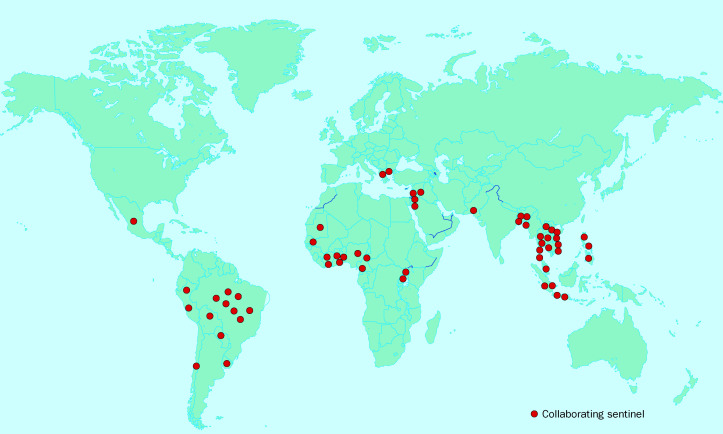

It is important to address these weaknesses in surveillance. Establishing a sentinel system may help to improve weaknesses by monitoring an area's situation more closely and directly. In 1998, we organised a study group, the Alumni for Global Surveillance network (AGSnet), which consists of experts and managers who participated in several infectious-disease courses that were sponsored by the Japan International Cooperation Agency (JICA) and organised by the Agency for Cooperation in International Health (ACIH).4 As of December, 2003, the group consisted of 60 sentinels in 29 countries (figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Map of sentinel distribution (as of December 2003).

AGSnet members are the principal government officials or managers who have experience in infectious-disease surveillance, management of patients, and/or control projects. At the request of ACIH, and after consulting with their supervisors, they agreed to form a study group to report to ACIH quarterly an update of selected diseases in their region with the. The detailed functions of the sentinels and target diseases are shown in table 1 . The criteria of individual target diseases are based on WHO Recommended Surveillance Standards, 1999, which was made available to all the sentinels by ACIH.5 Feedback from ACIH consists of selected information in the media—such as Reuters—of WHO surveillance reports including an outbreak verification list, the Weekly Epidemiological Record, the recent SARS update, and various surveillance articles published by medical journals. This information is not usually available to most of the sentinels, who are situated in areas where the health infrastructure is weak.

Table 1.

Target diseases for AGSnet sentinels

| Category | Description | Target infectious diseases |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Scientists dealing with clinical (or laboratory) diagnosis of patients, their treatment, follow-up care, and/or epidemic control in health institutions such as hospitals, outpost clinics, paediatrics department, or infectious-diseases control department | Cholera |

| Meningococcal meningitis | ||

| Acute flaccid paralysis (polio like) | ||

| Measles | ||

| Acute jaundice syndrome* | ||

| 2 | Scientists mainly doing laboratory work for pathogen identification, drug resistance, or any laboratory study on bacterial, viral, or parasitological agents obtained from specimens of infectious diseases | Influenza |

| Drug resistant malaria (clinical)† | ||

| Antimicrobial resistant typhoid fever (chloramphenicol, quinolones) | ||

| Japanese encephalitis | ||

| Plague | ||

| 3 | Scientists working in blood-transfusion services who can provide information on certain blood-borne diseases when blood is screened for such diseases | Dengue |

| Lymphatic filariasis‡ | ||

| Viral hepatitis B | ||

| Viral hepatitis C | ||

| HIV | ||

| Syphilis |

Aiming at hepatitis A, B, and E, and yellow fever.

Plasmodium falciparum or Plasmodium vivax.

Replaced by SARS in May, 2003.

AGSnet reports characteristically provide information about the occurrence of selected diseases via email without previous screening by the national reporting system. ACIH requests that AGSnet members do not seek or expand the search for information outside their own area of jurisdiction. Although this approach may limit the scope of reporting, we felt that a priority in this trial should be sustainability of sentinel activity, given that such sentinels usually handle a heavy workload with limited available resources. All sentinels function within their own limited resources and are approved by their national supervisors. The distribution of the sentinels shown in figure 1, however, shows some large areas without sentinels, an indication of the reluctance of some national authorities to permit free reporting or the absence of collaborating sentinels in those nations.

To assist the AGSnet, an advisory group consisting of Japanese experts and experts responsible for surveillance in WHO was formed. All the results are being sent to WHO, the advisory group, and individual sentinels, so that the information may be included in their overall pool of information for review and action.

Reports by AGSnet

Important reports by AGSnet over the past few years are described below.

Cholera and plague

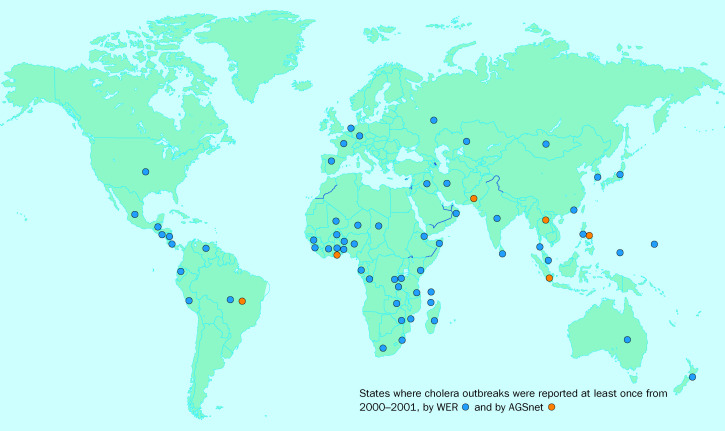

Both cholera and plague are quarantinable diseases whose containment worldwide depends on prompt reporting and follow-up. During 2000 and 2001, the WER recorded 229 cholera outbreak episodes from 61 states worldwide. 30 cholera (or suspected) outbreaks were identified by AGSnet, situated in six states. Of these AGSnet reports, 14 outbreak episodes from sentinels situated in three states were never reported in the WER (figure 2 ). Similarly, during the same period, plague outbreaks were reported from the sentinels in Laos and Brazil but were not reported by any other surveillance systems.

Figure 2.

Reported cholera outbreak by AGSnet sentinels and by WHO in 2000 and 2001.

Influenza

The influenza strain H5N1 is receiving special attention since it could introduce a pandemic, a probability that increases year by year. Each winter during the past 3 years AGSnet has reported a significant number of cases or suspected cases of influenza from Asian areas where avian influenza in poultry farms was being reported at alarming rates. Our sentinels in Vietnam and Laos each reported more than 4000 cases in each quarter of every year. In May, 2003, AGSnet added SARS as a target disease for notification. As of August, 2003, there had been no report of SARS from AGSnet, but a few sentinel officers expressed in their reports concern about their personal risk of SARS infection at their hospital workplace.

Dengue fever

The size of the epidemics reported is alarming. The sentinels in Brazil reported 20 000–40 000 cases each year from 1999 to 2001, and Laos reported 1000–4000 during the same period. In 2002, the WHO Executive Board noted the epidemics of dengue fever.

Polio and measles

AFP is specifically selected as a target disease since it is related to the polio-eradication endpoint.6 The number of cases of AFP reported by AGSnet in the states of each continent is declining (table 2 ). Measles reports by AGSnet sentinels in the Americas were few in 2002, and zero in 2003.

Table 2.

Reported acute flaccid paralysis (AFP) by AGSnet sentinels, 1998–2002

| Area and Country | Sentinel serial no | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Africa | ||||||

| Egypt | 1 | ·· | 0 | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Egypt | 2 | ·· | 0 | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Egypt | 3 | 118 | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Ghana | 4 | 0 | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Ghana | 5 | ·· | ·· | 2 | ·· | ·· |

| Ghana | 6 | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Senegal | 7 | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| South Africa | 8 | 60 | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| South Africa | 9 | ·· | 2 | 0 | ·· | ·· |

| Uganda | 10 | 0 | 6 | 1 | ·· | ·· |

| Zambia | 11 | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Zimbabwe | 12 | 0 | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Total | 178 | 8 | 3 | 0 | 0 | |

| Americas* | ||||||

| Brazil | 1 | 0 | 0 | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Brazil | 2 | ·· | 44 | 27 | 26 | ·· |

| Brazil | 3 | ·· | 5 | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Colombia | 4 | 0 | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Paraguay | 5 | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Uruguay | 6 | 0 | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Uruguay | 7 | 0 | 0 | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Total | 0 | 49 | 27 | 26 | 0 | |

| Asia† | ||||||

| Bangladesh | 1 | ·· | ·· | 0 | ·· | ·· |

| Fiji | 2 | 0 | 0 | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Indonesia | 3 | 0 | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Indonesia | 4 | 53 | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Indonesia | 5 | ·· | 11 | 13 | 15 | ·· |

| Indonesia | 6 | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | 0 |

| Laos | 7 | ·· | 93 | 67 | 54 | 38 |

| Laos | 8 | ·· | ·· | ·· | 35 | 14 |

| Pakistan | 9 | ·· | ·· | ·· | 10 | 0 |

| Philippines | 10 | 8920 | 42 | 91 | ·· | ·· |

| Philippines | 11 | 54 | 62 | 140 | 17 | ·· |

| Thailand | 12 | 0 | 0 | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Thailand | 13 | 0 | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Vietnam | 14 | 473 | 270 | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Vietnam | 15 | ·· | ·· | 2 | ·· | ·· |

| Vietnam | 16 | ·· | ·· | 2 | 0 | 4 |

| Total | 9447 | 478 | 315 | 131 | 56 | |

| Europe* | ||||||

| Bulgaria | 1 | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Total | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

| Middle East | ||||||

| Palestine | 1 | 0 | 0 | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Syria | 2 | 0 | ·· | ·· | 0 | 0 |

| Syria | 3 | 0 | ·· | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Syria | 4 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 |

| West Bank | 5 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | ·· |

| Total | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | 0 | |

Certification of polio eradication completed.

Certification of polio eradication completed only in Fiji, Laos, and Philippines, which belong to WHO Western Pacific Region.

Blood transfusion centres

Category-3 sentinels of AGSnet provide unique information about blood transmissible diseases. Table 3 shows the positive rates when screening tests were done for viral hepatitis B, viral hepatitis C, HIV, and syphilis. High and increasing rates were reported for hepatitis B in Africa and Asia. By contrast, hepatitis C and HIV-positivity rates were unexpectedly low, all being not more than 5% during 2000–2002. For some individual sentinels rates of hepatitis C positivity ranged up to 12·4%.

Table 3.

Reports from category 3 (blood bank) sentinels, 1998–2002

| Disease and area | Year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Viral hepatitis B | 1998 | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 |

| Africa | |||||

| Number of sentinels | 5 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 6 |

| Number of donors | 97979 | 50694 | 44590 | 84385 | 86741 |

| % positive | 2·52 | 4·41 | 3·96 | 5·20 | 5·89 |

| Americas | |||||

| Number of sentinels | 4 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Number of donors | 42968 | 58856 | 22772 | 58339 | 14240 |

| % positive | 1·42 | 0·01 | 0·54 | 0·41 | 0·46 |

| Asia | |||||

| Number of sentinels | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 |

| Number of donors | 186525 | 152665 | 539677 | 316052 | 6020 |

| % positive | 1·96 | 3·69 | 1·84 | 2·17 | 8·64 |

| Viral hepatitis C | |||||

| Africa | |||||

| Number of sentinels | 4 | 4 | 4 | 2 | 3 |

| Number of donors | 97689 | 48186 | 44025 | 58040 | 68515 |

| % positive | 5·81 | 5·14 | 3·18 | 2·58 | 1·61 |

| Americas | |||||

| Number of sentinels | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Number of donors | 42968 | 58856 | 22775 | 59340 | 13240 |

| % positive | 1·01 | 0·01 | 0·48 | 0·33 | 0·50 |

| Asia | |||||

| Number of sentinels | 6 | 5 | 5 | 4 | 4 |

| Number of donors | 69423 | 80180 | 494280 | 283073 | 5782 |

| % positive | 0·97 | 1·32 | 0·67 | 0·64 | 2·01 |

| HIV | |||||

| Africa | |||||

| Number of sentinels | 5 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 6 |

| Number of donors | 94109 | 49184 | 44590 | 82563 | 86741 |

| % positive | 0·51 | 1·98 | 1·89 | 1·44 | 1·40 |

| Americas | |||||

| Number of sentinels | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Number of donors | 42968 | 58856 | 22771 | 59339 | 14240 |

| % positive | 0·56 | 0·00 | 0·27 | 0·21 | 0·20 |

| Asia | |||||

| Number of sentinels | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 5 |

| Number of donors | 273652 | 168516 | 556772 | 339519 | 5782 |

| % positive | 0·29 | 0·30 | 0·14 | 0·21 | 0·93 |

| Syphilis | |||||

| Africa | |||||

| Number of sentinels | 2 | 6 | 4 | 4 | 4 |

| Number of donors | 29371 | 47034 | 44590 | 70792 | 76868 |

| % positive | 1·06 | 1·54 | 1·44 | 1·51 | 1·51 |

| Americas | |||||

| Number of sentinels | 5 | 4 | 2 | 2 | 1 |

| Number of donors | 42968 | 58856 | 22439 | 58426 | 14240 |

| % positive | 1·29 | 0·01 | 2·20 | 1·39 | 0·65 |

| Asia | |||||

| Number of sentinels | 6 | 6 | 6 | 6 | 4 |

| Number of donors | 158 760 | 109 038 | 501 772 | 302 078 | 5781 |

| % positive | 0·87 | 0·86 | 0·50 | 0·60 | 0·78 |

Discussion

The discrepancy between the numbers of cholera and plague outbreaks reported by WHO and AGSnet is an indication that careful assessment is still needed of how the global surveillance system safely follows up occurrence of these quarantinable diseases. To our regret, we have not pursued the discrepancy due to the informal nature of our system, and aim to improve our handling this problem in future.

Influenza and dengue fever were reported in large numbers from a few sentinels. There were very few reports of the disease in the WER over the same period. As the WHO influenza collaborating network indicates, more and more epidemic information, as provided by AGSnet specifically in tropical zones, would be desirable for the rapid discovery of critical epidemics. Increasing reports of dengue fever may be the result of global warming, suggesting that other arbovirus infections like malaria and Japanese encephalitis should receive special attention.

Polio and measles are diseases of particular interest in view of the WHO global polio eradication and regional measles elimination programmes. It is unfortunate that WHO missed the initial target year of 2000 in polio eradication. Lingering endemic transmission in seven states in Africa and the Indian subcontinent in 2001–2003 has been alarming—a lesson that intensified eradication efforts together with active surveillance should be short-term campaigns as discussed at the Dahlem Workshop.7 AGSnet measles reporting reflects the situation of the global measles programme—namely, that despite intensive surveillance, the WHO regional office for the Americas reported no cases for October, 2002, and the indigenous transmission was apparently stopped in 2003.8 However, overall reporting in other continents is poor, suggesting that many cases are not subject to effective surveillance. Measles surveillance needs a special strategy for large-scale or worldwide eradication.

Few cases were reported from AGSnet of acute jaundice, drug-resistant malaria, and Japanese encephalitis. It is important to note, however, that no report does not always mean no occurrence. Rather, it suggests that the surveillance sensitivity for these diseases is low, which may indicate the need for future special investigations to assess the magnitude of problems.

Category-3 sentinels deal with the prevalence of hepatitis B and C, HIV, and syphilis in blood donors. In the global surveillance network, surveillance data from blood-transfusion centres are not usually available in such a systematic way. The sensitivity of screening tests is also being assessed by the visits of our advisory group. HIV-positivity rates can be compared with reference to the AIDS Epidemic Update, December, 2002 (table 4 ).9 Towards the end of 20th century, high positive rates up to 12% were noted in Cameroon, Uganda, Cambodia, and Laos (table 5 ). However, as far as limited data from AGSnet is concerned, AIDS prevalence would seem to be in decline in these areas, although it should be borne in mind that blood donors may not be representative of the general population. The positive rates may differ between first-visit donors and repeat donors since the latter will be omitted if they are known to be HIV positive. Hence, lower positive rates may have been reported from the sentinel blood transfusion centres. Since AIDS epidemics cause worldwide concern, these findings require further research.

Table 4.

Regional HIV/AIDS statistics (end 2002)

| Area | Adult prevalence—estimate (%) |

|---|---|

| Sub-Saharan Africa | 8·8 |

| Southeast Asia | 0·6 |

| East Pacific | 0·1 |

| Latin America | 0·6 |

| Caribbean | 2·4 |

Source: WHO/UNAID AIDS Epidemic Update, Dec, 2002.

Table 5.

HIV/AIDS rates (%) reported by sentinels

| Year | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Country | 1999 | 2000 | 2001 | 2002 |

| Uganda | 13·38 | 11·28 | 2·94 | 1·78 |

| Cameroon | 11·44 | ·· | ·· | ·· |

| Cambodia | 3·74 | 2·58 | 2·70 | 2·28 |

| Laos | ·· | 3·20 | 3·08 | ·· |

Empty fields indicate data not available

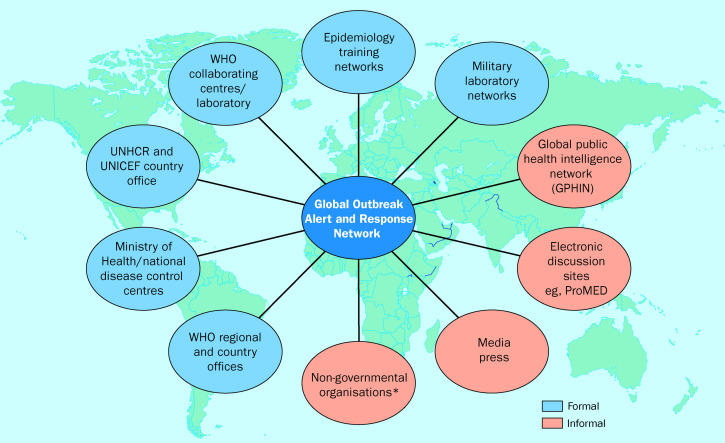

In recent years, the WHO global outbreak alert and response network (GOARN) has been functioning well (figure 3 ). Good examples were the surveillance and control of SARS and Ebola haemorrhagic fever.

Figure 3.

Global surveillance of communicable diseases: network of networks. *Including AGSnet. Adapted from a WHO original.

Reports of AGSnet and the analysis as described in this paper suggest that the system may become a regular supplier to the GOARN global database in collaboration with ACIH and JICA. Such data may include new or emerging diseases that could have potential to threaten international health security. Although the system's geographical coverage is limited, during the operation over the past few years it has proved to be unique in terms of persistent electronic, realtime exchange of information, and willingness to provide directly the information from resource-poor areas.

Whilst we feel that the AGSnet system is useful enough to continue working, further effort should be made to improve and strengthen the function. Prioritisation of target diseases will be a critical issue. Surveillance would be more sensitive if AGSnet targeted fewer and more important diseases. It would be desirable to organise an international conference of individual sentinels of AGSnet to optimise strategy and logistics in view of the increasing disparity of surveillance sensitivity between different states and regions. There are training courses in field epidemiology organised by a few institutions, such as the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, WHO, Medicins sans Frontieres, and JICA. It would be useful for the sentinels to participate in course as the opportunity arises. The quality of AGSnet collected information should be further examined—eg, for its sensitivity, timeliness, stability, and sustainability.10 During the initial phase of the AGSnet system, there was no record of how surveillance information was translated into actual public-health action. Future development of this area would be a critical element for ACIH to pursue.

Lastly, the bottom line for surveillance should simply be “case notified without suppression”. But negligence often results in disastrous epidemics. During the final phase of smallpox eradication a few national programmes, fearful of blame for being the last smallpox state, suppressed case reports either at national level or district level. This policy resulted in epidemics. The recent SARS epidemic falls into the same category. But these programmes succeeded in the rapid elimination of hidden foci, once they started to report all cases and initiated containment.

Conclusion

AGSnet is a voluntary study group of a sentinel surveillance system. Its aim is to add more disease information, as necessary for global epidemiological surveillance headed by WHO. The results of AGSnet obtained so far indicate that the system was able to discover some valuable information on infectious diseases of international importance, happening in special areas. Although the information is irregular, it may be added to the WHO pooled surveillance data worldwide. Further development of this system seem to be desirable, including assessment as regards its sensitivity and resulting public-health action. It should be noted, however, that such network in no way replaces or negates the need for strong national surveillance, alert, and response mechanisms.

Acknowledgments

Acknowledgments

We thank our fellow sentinel officers who have contributed diligently to this study despite their busy schedules and limited resources. Our thanks also to our advisory group as well as to Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare, Japan, and JICA for their support to the development of this study system. Our special thanks go to D A Henderson, Johns Hopkins Medical School, J Breman, Fogarty International Centre, J Wickett, WHO, and K Yamaguchi, Blood Transfusion Service, Kumamoto University Hospital, for their encouragement and advice.

Conflicts of interest

None declared.

References

- 1.Fenner F, Henderson DA, Arita I. Smallpox and its eradication. WHO; Geneva: 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Report of the interim meeting of the Technical Consultative Group (TCG) on Global Eradication of Poliomyelitis. WHO/V&B/30.04. WHO; Geneva: November, 2002. pp. 13–14. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Update: Multistate outbreaks of monkeypox. June 20, 2003. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2003;52:561–564. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Global surveillance of emerging and re-emerging diseases—a pilot sentinel network project. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2001;76:218–224. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organisation . WHO Recommended Surveillance Standards, 2nd edn. WHO/CDS/CSR/ISR/99/2/EN. WHO; Geneva: 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nomoto A, Arita I. Eradication of poliomyelitis. Natlmmun. 2002;3:205–208. doi: 10.1038/ni0302-205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Arita I. Are there better global mechanisms for formulating, implementing, and evaluating eradication programme? In: Dowdle WR, Hopkins D, Hopkins DR, editors. Dahlem workshop on the eradication of infectious diseases. John Wiley & Sons; London: 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Anon. Six weeks without reported indigenous measles transmission in the Americas. EPI Newsletter. 2002;24:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 9.UNAIDS & WHO . AIDS epidemic update. UNAIDS/02.58E; Geneva: December 2002. http://www.who.int/hiv/pub/epidemiology/epi2002/en/ accessed Feb 10,2004. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Updated guidelines for evaluating public health surveillance systems—recommendations from the guidelines working group. MMWR Morbid Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50:1–35. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]