Dear Editor:

Human parechoviruses (HPeV), previously designated as echovirus 22 and 23, belong to the Parechovirus genus within the Picornaviridae family and has been designated HPeV 1 and 2 respectively.1 The HPeV genome organization and disease spectrum are similar to other viruses in the Picornaviridae family. HPeV have been frequently associated with respiratory and gastrointestinal diseases in children and severe disease in neonates that includes sepsis, meningitis, encephalitis, and hepatitis.2 In Brazil, HPeV type 8 was first reported in a gastroenteritis outbreak, where 35 stool samples were analyzed and 16.1% were HPeV positive.3 Highlighting HPeV as etiology of respiratory infection, the authors report the case of a 2-year-old girl with signs and symptoms of sepsis-like illness which progressed to sepsis with pulmonary focus. She was admitted to the pediatric emergency unit in a tertiary care hospital in Southern Brazil, with previous history of rhinorrhea, otorrhea and fever for seven days, and dry cough, poor food acceptance and emesis with grunting episodes in the three days prior to admission. Previously, the patient had two hospitalizations for pneumonia at the age of eight and 15 months. The mother reported meningitis outbreak at the patient's daycare 15 days before, and the child had the vaccination protocol updated. Upon admission, the patient weighed 13 kg, had tachycardia (175 beats/min) and tachypnea (33 breaths/min), was in poor general condition, whining, pale, sleepy, with reduced vesicular murmur, fine crackles and dullness to percussion of left pulmonary lower medium-third. The lung ultrasound showed a small pleural effusion of 0.5 cm thick, with no need of drainage. The patient progressed with respiratory insufficiency, altered consciousness level and septic shock requiring ICU monitoring and mechanical ventilation and her oxygen saturation was 91%. The patient had hemodynamic instability, requiring vasoactive drugs, metabolic acidosis and altered renal function. X-rays showed an acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS) pattern (Fig. 1), with bronchopneumonia and pulmonary edema; progressed with decreased urine output and worsening of urea and creatinine levels compared to the admission, which was managed with plasma, albumin and furosemide administration. She had a favorable outcome, and was discharged eight days after the admission. Microbiological investigation was negative for bacteria on blood and respiratory secretion. Respiratory viruses were surveyed in nasopharyngeal aspirates (NPA) using a PCR multiplex method (RV 15, Seegene®, South Korea), which detects respiratory syncytial virus A and B, adenovirus, influenza A and B, parainfluenza 1, 2, 3 and 4, human metapneumovirus, coronavirus OC43 and 229, human rhinovirus A, B and C that resulted negative. By molecular methods a conventional RT-PCR, to the 5′NCR as a target, was performed in NPA and detected HPeV, which was confirmed by nucleotide sequence method (Fig. 2).1 To our knowledge, this is the first report of HPeV circulation in south Brazil. Currently, 16 types of HPeV are recognized and reported mainly in patients under five years old. HPeV have a worldwide distribution and have been reported in many clinical conditions such as gastroenteritis, respiratory infections, neonatal sepsis, various and severe CNS diseases, including paralysis, meningitis and encephalitis. Each condition has been associated with different HPeV types.2 Respiratory symptoms, have been frequently reported in children with HPeV infections. Two recent studies investigating the involvement of HPeV in respiratory diseases detected HPeV1, HPeV3, and less frequently HPeV 4, 5 and 6 in children below five years old. However, these studies report low frequency of detection and high rate of co-infection with other respiratory viruses, hence preventing the elucidation of the role of these viruses in respiratory infections.1, 4 Blood culture, considered the gold standard for neonatal infection diagnosis, has poor sensitivity (8–73%) and will not detect all pathogens and very little is known about non-bacterial pathogens as a cause of late onset infection. Davis et al. (2015) described the detection of HPeV 1 in a group of preterm infants in neonatal intensive care. In the total group, 13% of infants had HPeV type 1 infection confirmed by PCR method.5 In recent years, viral community-acquired pneumonia (CAP) has been reported as a frequent microbial etiology in severe CAP. This is in part due to new diagnostic techniques that allow detecting old and new viruses, such as Middle East Respiratory Syndrome (MERS), one of these new viral diseases, which is caused by an RNA betacoronoravirus.4 Neonates and young children are more vulnerable to infections than older children or adults. In this context, HPeV is now recognized as an important agent for infectious diseases and currently has 16 identified genotypes. Each genotype is related to various clinical patterns and by molecular methods HPeV 1 and 3 are the most frequent types involved in many severe infectious.2 This study shows a case of sepsis with pulmonary focus associated to HPeV infection and should serve as a warning to the introduction of this investigation in the routine care of patients with severe respiratory infection, meningitis, gastroenteritis, or neonatal sepsis, promoting epidemiological and longitudinal analyses seeking to understand the dynamics of this virus circulation and its impact on children's health.

Fig. 1.

X-ray reveals an acute respiratory distress syndrome (ARDS).

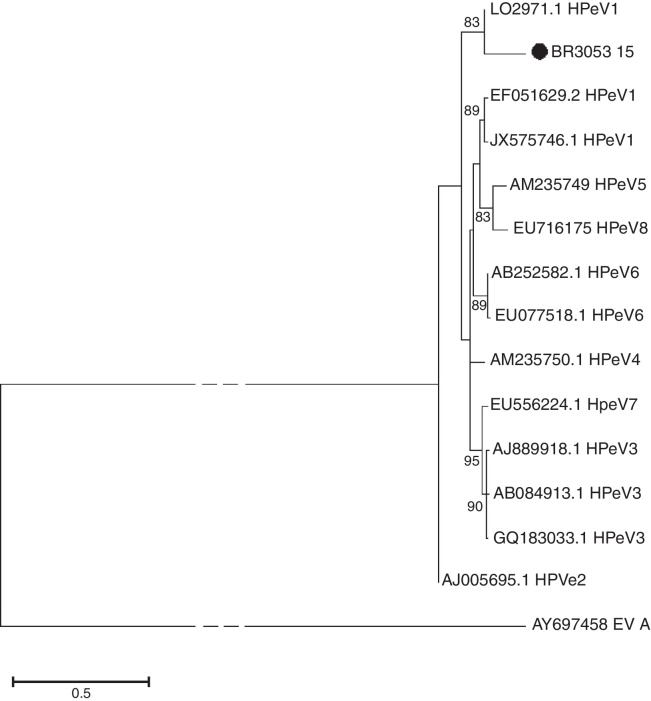

Fig. 2.

Phylogenetic analysis of HPeV constructed by Maximum-Likehood method. Partial 5′UTR sequences were compared. Reference strains, published in GenBank, were included for comparison. Strain of this study is shown as circle symbol. Branches to the EV-A node have been truncated, as indicated by dotted lines. Only bootstrap values >75 are shown (1000 replicates).

Authorship

Luine R.R. Vidal wrote the first draft of the manuscript. Sérgio M. de Almeida assisted the patient and contributed to describe the clinical course. Bárbara M. Cavalli was involved in the development of molecular methods that include the cloning of the positive sample, as well as in the standardization and validation of the molecular methods. Sonia M. Raboni assisted the patient and contributed to describe the clinical course. Meri B. Nogueira was the study's supervisor.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thanks Dr. Willian Allan Nix from the Polio and Picornavirus Laboratory Branch, Division of Viral Diseases, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, Atlanta, USA for providing the HPeV positive control. Also to Heloisa Giamberardino and Luciane Aparecida Pereira for special contributions.

References

- 1.Harvala H., Robertson I., Mcwilliam L.E.C., et al. Epidemiology and clinical associations of human parechovirus respiratory infections. J Clin Microbiol. 2008;46:3446–3453. doi: 10.1128/JCM.01207-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Harvala H., Wolthers K., Simmonds P. Parechoviruses in children: understanding a new infection. Curr Opin Infect Dis. 2010;23:224–230. doi: 10.1097/qco.0b013e32833890ca. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Drexler J.F., Grywna K., Stöcker A., et al. Novel human parechovirus from Brazil. Emerg Infect Dis. 2009;15:310–313. doi: 10.3201/eid1502.081028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leung C.H., Gomersall C.C.D. Middle East respiratory syndrome. Intensive Care Med. 2014;40:1015–1017. doi: 10.1007/s00134-014-3303-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Davis J., Fairley D., Christie S., et al. Human parechovirus infection in neonatal intensive care. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 2015;34:121–124. doi: 10.1097/INF.0000000000000510. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]