Abstract

The global spread of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has caused sudden and dramatic societal changes. The allergy/immunology community has quickly responded by mobilizing practice adjustments and embracing new paradigms of care to protect patients and staff from severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 exposure. Social distancing is key to slowing contagion but adds to complexity of care and increases isolation and anxiety. Uncertainty exists across a new COVID-19 reality, and clinician well-being may be an underappreciated priority. Wellness incorporates mental, physical, and spiritual health to protect against burnout, which impairs both coping and caregiving abilities. Understanding the stressors that COVID-19 is placing on clinicians can assist in recognizing what is needed to return to a point of wellness. Clinicians can leverage easily accessible tools, including the Strength-Focused and Meaning-Oriented Approach to Resilience and Transformation approach, wellness apps, mindfulness, and gratitude. Realizing early warning signs of anxiety, depression, substance abuse, and posttraumatic stress disorder is important to access safe and confidential resources. Implementing wellness strategies can improve flexibility, resilience, and outlook. Historical parallels demonstrate that perseverance is as inevitable as pandemics and that we need not navigate this unprecedented time alone.

Key words: Wellness, Physician wellness, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19, Pandemic, Social distancing, Burnout, Depression, Grief, Mindfulness

Abbreviations used: CFR, Case-fatality rate; COVID-19, Coronavirus disease 2019; PPE, Personal protective equipment; SARS-CoV-2, Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2; TB, Tuberculosis

Introduction

Despite global awareness of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2) since December 2019, coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has become a global pandemic that caught the world unprepared in the early months of 2020.1 It is now clear that SARS-CoV-2 is highly contagious, capable of causing severe pneumonia, acute respiratory distress syndrome, and death, particularly in vulnerable populations such as older adults and those with chronic medical conditions, such as cardiovascular disease, diabetes, respiratory disease, hypertension, and malignancy.2 , 3 Strategies are being implemented to “flatten the curve” of the pandemic to preserve capacity and not outpace the availability of precious health care resources. The current supply of personal protective equipment (PPE), intensive care unit beds, and ventilators may not be able to keep up with projected demands.2 , 4 This nightmare scenario has been experienced internationally, with countries such as Italy and Spain overwhelmed, and looming concerns that this may occur in certain parts of the United States.5 For example, the percentage of symptomatic patients with COVID-19 requiring intensive care unit care has been between 9% and 11%.6 Demonstrating the rapidity of spread, the first recognized case of the pandemic in Italy appears to have been a young man admitted in the Lombardy region with atypical pneumonia on February 20, 2020, and health care resources were overwhelmed within a few weeks.5 The timeline of the Italian experience illustrates a major reason for COVID-19–induced anxiety around the world (Figure 1 ).5

Figure 1.

The coronavirus pandemic in Italy. Reproduced from Livingston and Bucher.5

Attempts to mitigate the impact of COVID-19 have disrupted core aspects of society. Social distancing is central to efforts to control the pandemic.4 However, to be effective, social distancing must be rapidly and universally adopted across a society, which sadly has occurred to varying degrees across the globe. Risk perception is likely a significant lever on the degree to which populations embrace a social distancing approach.7

During a pandemic, both medical experts and governmental authorities require a high degree of accurate knowledge and trust to execute effective policies.8 Tragically, there has been a vacuum of unified societal knowledge and trust throughout this pandemic. For example, a recent cross-sectional survey of the general public in the United States and the United Kingdom found that, of 2986 US and 2988 UK adults, 23.9% and 18.4%, respectively, believed SARS-CoV-2 to be a bioterrorist weapon.8 When asked between February 23 and March 2, 2020, 61% of US and 72% of UK respondents thought the number of people who would die of COVID-19 in their respective country would be fewer than 500 persons.8

In response to the medical community, local government, and concerned citizen frustrations with currently available policies and demands for detailed accurate information, our knowledge of COVID-19 is rapidly expanding.9 Unfortunately, the spread of the virus also continues to rapidly increase, with the Johns Hopkins Coronavirus Resource Center listing 607,965 total confirmed cases and 28,124 deaths as of March 27, 2020.10 The case-fatality rate (CFR) of COVID-19 is being scrutinized.11 Early data from China estimated the CFR to be 2.3% of symptomatic patients presenting for medical evaluation, with rates as high as 15% in vulnerable elderly populations.3 , 4 In patients with critical illness, CFR has been reported to be as high as 49%.3 Although CFRs may actually be much lower when mild and asymptomatic cases are considered, the Italian CFR is 7.2%5 (Figure 1). Much of these data are hindered by lack of knowledge regarding the total number of cases. Health care worker fatalities were noted early and continue to rise in the United States.3 , 4 In an early report from China, 3.8% of cases occurred in health care workers, and 14.8% of these were classified as severe, with a CFR of 0.3%.3 , 4 In Italy, more than 50 physicians have died of COVID-19 as of March 27, 2020.12

Despite this rising tide of illness, there is room for hope. Although the pace of change demanded in our response to COVID-19 is disorienting, it is important to note that, globally, 145,625 patients with confirmed cases have recovered as of March 29, 2020.10 There is a growing awareness of the need to protect health care workers from SARS-CoV-2 infection.13 However, in addition to an urgent need to prevent infections related to patient care, there is also a growing need to address broader aspects of wellness among health care workers.

The COVID-19 pandemic has created sudden stressors across many domains of our lives that become apparent when viewed through different lenses, including the theory of knowledge (“you don't know what you don't know,” information vs misinformation), appreciation of system capacity (both health and economic), understanding warranted and unwarranted variation, and human psychology.14 To survive COVID-19 and its aftermath requires care directed toward our patients as well as ourselves and our families. Although tending to personal wellness is always important, it has become even more crucial during these extraordinary times. Understanding risks and consequences of burnout magnified by COVID-19; identifying historical parallels of the pandemic while appreciating new challenges of social media; leveraging new technologies to care for patients, staff, colleagues, and ourselves while managing responsibilities at home; and using wellness resources at the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, the American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, the Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology, and state physician health programs as needed can help each of us navigate uncharted waters together, even while practicing social distancing.

Clinician Wellness

Clinician wellness involves a number of factors including stress and burnout.15 These factors can impact negatively on patient care and lead to increased medical errors, malpractice risk, and early retirement.15 Greater clinician stress may lead to higher rates of drug and alcohol addiction, divorce, and suicide.15 Clinicians are more likely to have burnout symptoms than the general US workforce and are more likely to be dissatisfied with work-life balance.16 Even before this pandemic, burnout rates among US physicians overall were estimated to be at around 46%.16 Female physicians have higher rates of burnout.17 A recent survey revealed a burnout rate of 35% among US allergy and immunology physicians in the United Ststes.18

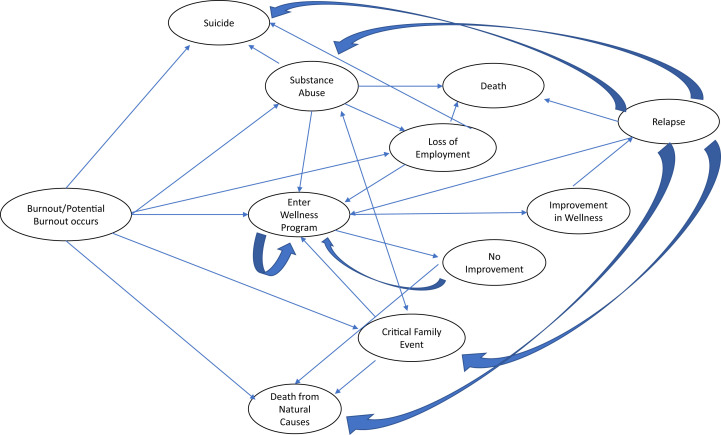

Higher rates of burnout may be associated with certain clinician attributes, including belief in service and sense of duty, perfectionism, and personal internalization of patient outcomes.19 Day-to-day office-based stressors include clerical burden (eg, electronic medical record documentation), excessive nonclinical and clinical workloads, and practice inefficiencies.15 , 20 Although medical practice demands may contribute to burnout most significantly, personal and family stressors may add additional pressures.15 The current COVID-19 pandemic has disrupted the health care system worldwide. A prolonged response to the pandemic will lead to additional stress for clinicians and their support staff and further permeate throughout the health care system.13 Consequences of burnout are shown in Figure 2 .

Figure 2.

Health state transition and outcomes of burnout. A listing of state physician health programs is available at the Web site of the Federation of State Physician Health Programs.21

COVID-19 Challenges to Wellness

In the setting of a global pandemic it is normal to be frightened for one's own personal safety (and potential mortality), particularly with data emerging about airborne and fomite transmission, exposure risk from asymptomatic carriers, limited testing, and well-publicized issues regarding conflicting advice about what level of PPE is necessary or available. Finding evidenced-based PPE recommendations is difficult; however, over a 2-week span, the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention downgraded the COVID-19 risk from airborne to droplet (outside of an aerosol-generating procedure).2 Changing recommendations have been a cause of anxiety for clinicians, compounded by employment termination concerns in some instances for wearing precautionary PPE.

In a crisis, physicians may feel their medical oaths tested when confronted with ethical dilemmas that are intrinsic in rationed care due to equipment shortage or institutional policy of universal do not resuscitate status for COVID-19–positive patients. As the psychological stressors are evolving day by day, non–intensive care unit/emergency department physicians may be redeployed to less familiar (and critical) clinical areas. Questions regarding the ethics of providing care outside of one's scope of practice, and the associated liability, are evolving. The American Medical Association released an update to its code of medical ethics on March 20, 2020, specifically addressing these issues in Opinion 8.3 and Opinions 11.1.2 and 11.1.3.22 These may help provide an ethical backdrop on how to approach such situations, though this still may not do much to leverage preserving one's own wellness and ability to persevere in such circumstances. In New York state, Governor Cuomo has introduced legislation limiting any malpractice liability to physicians practicing outside of their scope, except in cases of gross negligence (which remains nebulously defined).23 However, outside of New York, such liability protection is unclear and may cause justifiable concern.

Many hospitals and health care systems are recognizing the stress and strain on their clinicians. Some have made counselors available and have been offering free access to online tools for meditation and relaxation. A plethora of such online tools exist, and sometimes a quick breather may serve as a way to recharge and regain some wellness, at least momentarily, when under stress. Multiple businesses have recognized the heroic efforts of the medical community and are offering free services—sometimes just a free coffee and donut may be enough to show that one's efforts are being appreciated. The real concern is that in stressful times, there is a temptation to self-medicate or resort to less productive and more self-harmful solutions—drugs and alcohol in particular, which may increase the risk for suicide and domestic violence. Physicians at baseline work high-stress jobs and are already prone toward issues, including marital problems, and substance abuse, that may become magnified in this particular crisis.

Change, Loss, Guilt, and Grieving

Change is difficult, and during COVID-19 change has been rapid and associated with both uncertainty and with varying degrees of loss. Guilt and grieving are also major considerations for our wellness. Elizabeth Kubler Ross defined 5 stages of grieving: denial, anger, bargaining, sadness, and acceptance.24 More recently, these stages have been updated to disbelief, yearning, anger, depression, and acceptance, with the depression peaking at approximately 6 months postloss, and acceptance not until 24 months postloss25 (Figure 3 ). Some of these stages may be more identifiable, though loss in the midst of this crisis may be harder to define, and may vary considerably on the basis of personal experiences. When the disease was abroad, there may have been denial/disbelief as to the severity and yearning for limited effects on our society. As testing kits and PPE have been deficient, anger at the government and administration is being felt. Physicians may find themselves bargaining for any way out as they are called to make life or death decisions.

Figure 3.

Stages of grief. Elizabeth Kubler Ross defined 5 stages of grieving: denial, anger, bargaining, sadness, and acceptance. More recently, these stages have been updated to disbelief, yearning, anger, depression, and acceptance, with the depression peaking at approximately 6 months postloss and acceptance not until 24 months postloss. Reproduced from Maciejewski et al.25

Undoubtedly, how we practice allergy has already changed, and in addition to health risks physicians face the looming reality of economic loss and associated anxiety. As COVID-19 becomes pervasive around us, there is a need to appreciate the potential for our own countertransference in considering our own personal and familial needs versus the needs of our patients and colleagues. This may be more difficult for some than for others. Naturally, we will all likely experience some degree of guilt and grieving for a number of potential reasons. However, as we may all cycle through these aforementioned stages, there is the final stage of acceptance as we find our way forward. Remind yourself this is a normal, healthy part of wellness, and things will hopefully change for the better.

A Historical Perspective

Historically, one can draw an analogy to tuberculosis (TB). In the 19th century, tuberculosis was responsible for 1 in 7 deaths. Like COVID-19, TB mortality also significantly impacted physicians. It was not until 1882 that Dr Edward L. Trudeau discovered the TB bacterium that caused the disease, and in 1896, when he opened the first sanatorium at Saranac Lake, NY, patients sat outdoors on the wide sun porches to take the “fresh air cure” and receive state-of-the art management of that era.26 Unfortunately, fresh air did not cure TB, and it was not until simple public health social distancing that TB declined sharply in the 1920s and 1930s. The societal struggle with TB demonstrates several parallels with the COVID-19 pandemic. Foremost is the clear and present danger posed by an infectious agent for which curative therapy is currently unavailable and for which only symptomatic management can be provided. This creates challenges to both health and wellness, because fear, anxiety, and frustration can threaten to overtake a rational approach to managing the situation of the moment.

A second parallel with TB is the temptation to embrace unproven therapies. For example, in the early 1880s, interventions used to treat TB included “collapse therapies,” in which physicians performed an elective pneumothorax, with the rationale for this procedure being to deprive the aerobic Mycobacteria of oxygen, in an attempt to kill them.27 This procedure involved injecting oxygen or nitrogen into the chest cavity with increasing pressure until the lung collapsed. However, this collapse was not permanent, and it required repeating the procedure every few weeks. It has been estimated that more than 100,000 patients underwent this procedure in the 25 years after this technique was developed, despite the fact that there were no rigorous studies conducted at the time to confirm its effectiveness.28 It was not until 1943 that Albert Schatz discovered streptomycin, which initially proved successful as TB monotherapy, but, over time, combination therapy was required.29 Similarly, trials are actively ongoing to treat COVID-19, including new antivirals, the use of hydroxychloroquine with azithromycin, anti–IL-6 agents, and the development of vaccines to name just a few.4

We can learn from our past and realize that, even in the darkest times, there will be a bright future someday. As physicians our calling is to care for those in need. Ultimately, validation of effective treatments will lead to greater physician empowerment. In the meantime, wellness tools and strategies can help to manage our fears and anxiety while we practice medicine with the tools we have in the moment.

Social Media During a Global Pandemic: The Good, the Bad, and the Ugly

With billions of active users across various social media platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram, the manner in which we communicate and receive information has fundamentally changed. We have unprecedented instant access to information on a scale the world has never seen before.30 Before the introduction of Facebook in 2006, including during the early stages of the internet, we relied on a limited number of vetted resources for information, namely major media outlets or the daily newspaper. In 2020, however, we live in the age of “FakeNews,” and internet users need savviness and knowledge to identify factual information and ignore misinformation.31 The opinions of celebrities, accounts with large numbers of followers, and online influencers are artificially equated with those of actual medical experts. This constant stream of information (and misinformation) can be overwhelming for anyone, let alone clinicians already facing stressful challenges in their professional and personal lives. Before COVID-19, internet addiction was already recognized as a growing problem contributing to social anxiety, attention deficit/hyperactivity disorder, and other aspects of wellness, which may only intensify during these trying times that are constantly reminding us of the stakes we face.32 During a global pandemic, social media utilization can be beneficial for updates of important information related to current precautions and best practices and provide connections to needed resources. It can also help to connect physicians with loved ones across the globe who are having similar fears and are socially distanced. There are simple, yet effective, strategies that merit review for all medical professionals who use social media in order to maximize benefit and mitigate risk (Table I ). More information on managing social media during the pandemic is included in this article's Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org.

Table I.

Tips to maximize the benefits of social media as a medical professional

| Mindfulness |

|

| Productivity |

|

| Reaching a target audience |

|

| Professionalism |

|

| Balancing clinician wellness during COVID-19 |

|

Depression, Substance Abuse, and Suicide

There is a relative paucity of data and unknown prevalence regarding physician depression.15 Systematic reviews of medical students and residents showed depression prevalence at 27% and 29%, respectively.15 , 33 , 34 A 2020 Medscape survey of approximately 15,000 physicians revealed a rate of depression of 15% to 18%.35 Unfortunately, clinicians likely have incentive to conceal symptoms of depression for fear of putting hospital privileges or medical licenses in peril.15 Thus, the prevalence is likely to be underestimated.15

Suicide rates for physicians are estimated to be higher than for the general public, and higher in female versus male physicians.15 , 36 Physicians are more likely than nonphysicians to succeed in suicide attempts.36 The 2020 Medscape survey revealed that 21% to 22% of physicians had suicidal ideations and 1% to 2% had attempted suicide.35 Risk factors for suicide include depression, being single, not having children, substance abuse, access to drugs, and associated stress and burnout.36 , 37 This has unfortunately also affected our field of allergy and immunology.15

Although the exact prevalence of alcohol and drug addiction among clinicians is not known,15 physicians are not immune to substance abuse or exempt from personal tragedy of the current opioid epidemic.15 Unfortunately, stigma remains among clinicians reporting depression, substance abuse, addiction, and those attempting suicide.15

With the increasing stresses and uncertainty regarding COVID-19, the clinician may be at an even greater risk. In fact, more than 70% of health care workers in China during this current pandemic reported psychological distress including insomnia, anxiety, and depression.38 Addressing these issues with a mental health care professional may be needed, and it is important to understand warning signs of depression, anxiety, posttraumatic stress disorder, alcoholism, and substance abuse. Besides detection, understanding how to access safe and confidential resources to get help is key. In fact, most states have resources for clinicians seeking help through self-referral for depression, alcoholism, and/or substance abuse, and accessing these resources is confidential and does not need to interfere with licensure or medical practice. A listing of state physician health programs is available at the Web site of the Federation of State Physician Health Programs.21

Promoting Wellness While Maintaing Oupatient Practice During COVID-19

COVID-19 is adding to nonpandemic stresses of allergy and immunology physicians in practice, regardless of the clinical setting. For example, allergic conditions and COVID-19 symptoms have some overlap.39 Lack of information regarding COVID-19 testing also can increase anxiety of both clinician and patient. Allergy and immunology services such as biologic therapy and immunoglobulin replacement therapy are medically necessary and keep patients out of the emergency department and hospital, potentially saving resources for the care of the COVID-19 patient.40 However, recent guidance has suggested approaches such as telehealth when service reductions are required.4 Appropriate triage during the pandemic allows for effective social distancing; however, economic realities of service adjustments are inescapable, and the consequences of managing reduced revenue will create challenges to staff retention and maintaining a practice. Federal stimulus legislation may provide some relief of economic pressures during the pandemic. Advice to improve resilience during this time is outlined in Table II .41, 42, 43, 44 More information on wellness at work and cost-effectiveness of physician wellness is included in this article's Online Repository at www.jaci-inpractice.org.

Table II.

Tips for allergy and immunology practice resilience during the COVID-19 pandemic

| Use telehealth |

|---|

| Postpone nonessential patient visits and procedures |

| Create a practice task force for addressing and implementing changes |

| Train staff on implemented changes |

| Collaborate with other allergy and immunology colleagues |

| Review practice finances and plan for income changes |

| Overcommunicate with patients |

Working at Home with Children

During the pandemic, school closures add a layer of complexity to finding a work-life balance. In addition, there are different family units, including single physician parent households, with various custody arrangements. Parents of older children are coping with a unique set of stressors trying to help them navigate an uncertain landscape. High-schoolers currently applying to college are concerned because standardized college admissions tests and advanced placement examinations are being canceled, and they are unsure as to how this will affect their college admissions process. Many college students are anxious about whether their summer internships will be canceled, whether graduate degree programs will understand and accept that many colleges and universities are only providing pass/fail grades this semester, and how they will complete courses that depend on face-to-face interactions, which range from the performing arts to chemistry labs. Many seniors are grieving the loss of graduation ceremonies or are worried that their postcollege full-time job offers will be rescinded. Across the spectrum of pediatrics, children with special needs require increased supervision, and parents may need to work in shifts to provide one-on-one attention. All these factors translate to added stress on clinicians and patients alike.

Working from home while supervising clinical and/or research activities is challenging and requires new workflows. In this setting, clinicians must balance electronic medical record communication and respond to urgent and routine messages. First, it is important to establish frequent, consistent video and/or phone communication with staff and assign bite-sized tasks. Breaking larger assignments into smaller concrete blocks can prevent overwhelming colleagues, increase empowerment, and nurture a sense of accomplishment and satisfaction. Second, it is important to realize that everyone is adjusting to new pandemic realities. Additional advice on working with kids at home is depicted in Table III .45, 46, 47

Table III.

Suggested strategies for being productive at home with children of different ages

|

Coping and Wellness Tools

Now more than ever, health care providers need to practice self-care. Coping with rapidly changing recommendations can become overwhelming, while stress and anxiety can become insidious bedfellows escalating a cycle of tension both at home and at work. Paradoxically, at a time when social distance is strongly encouraged, we can all find ourselves more interwoven with one another in a common struggle to persevere against an unimaginable global challenge. While we face the defining moment of our time, resilience, compassion, and serenity may be great assets.

Many of us are filled with a mix of complicated emotions at this time. Strategies that have worked for us in the past, like getting together in person with friends, family, or colleagues, are not available while practicing social distancing. This loss of personal connectivity leads to further struggles for many. At this time, we need to look for ways to connect virtually and ensure we are attending to clinician wellness. This pandemic is unlike anything most have experienced before; however, we are able to draw from our collective experience with previous tragedies and struggles, including September 11, 2001, Hurricane Katrina, severe acute respiratory syndrome, and H1N1 flu epidemics.

The Strength-Focused and Meaning-Oriented Approach to Resilience and Transformation, which is typically used by social workers after a crisis to help survivors develop resilience to get through and transform and grow in the process, can be used today in our present crisis.48 The framework uses mind, body, and spirit approaches to foster awareness, develop strength, and discover meaning. It addresses this through “emphasizing growth through pain” by focusing on what personal strengths may develop through the experience. It “teaches the mind-body-spirit connection” in recognizing that by taking care of our physical needs we can boost our mood and mental strength. Furthermore, “developing an appreciation of nature,” we are encouraged to appreciate the small things in life, appreciate our own life, and those of loved ones around us. By “facilitating cognitive reappraisal” we can develop new perspectives and remember resilient experiences during other crisis and past successes. “Nourishing social support” allows us to improve and enhance our development and resilience while simultaneously having a sense of acceptance and connectedness while learning to recognize and appreciate the support offered from those around us. The final tenet of this approach includes “promoting the compassionate helper principle” in which we learn from traumatic experiences by extending compassion to ourselves and others.

Even in the best of times, health care professionals often do not seek assistance when they are experiencing stress, burnout, depression, and suicidality because of concerns regarding confidentiality, cost, time, licensing and career concerns, and stigma. Pospos et al49 selected and evaluated several Web-based resources according to the American Psychiatric Association “app evaluation framework”50 to be used as a starting point to address depression, stress, and suicidal ideation, noting that ideal interventions would be effective, “convenient, accessible, affordable, and confidential” and ideally would be used in conjunction with direct professional care. The resources chosen would inocorporate the treatment approaches used to address burnout among health care professionals: meditation, breath work, relaxation techniques, mindfulness training, cognitive-behavioral therapy, and suicide prevention. The applications it recommended include Breath2Relax, Headspace, MoodGYM, Stress Gym, Stay Alive, and Virtual Hope Box. Of note, the only one that has been assessed for efficacy in health care professionals was MoodGYM, which was shown to reduce suicidal ideation among medical interns.51 Mindfulness-based therapy platforms can allow for a sense of community, connectedness, and a platform to share successes and promote resilience.52 Additional wellness resources are outlined in Table IV .

Table IV.

Physician wellness resources

| Online resources |

|---|

| AAAAI Physician Wellness Toolkit53 |

| AMA steps forward54 |

| Stanford WellMD55 |

| Institute for Healthcare Improvement56 |

| Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine (AAIM), Collaborative for Healing and Renewal in Medicine (CHARM)57 |

| Meditation and mindfulness apps |

| Art of Living - Online Happiness58 Program for Healthcare Workers (no charge during COVID-19) |

| Headspace59 |

| Ten percent happier60 |

AAAAI, American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology; AMA, American Medical Association.

At this time of social distancing it is important to maintain a schedule and your morning routine even if you do not have to leave the house. Enjoy nature while maintaining social distances. Take the time to connect with others virtually if you are feeling lonely via phone, email, and video platforms.61 When feeling overwhelmed by the number of people in the house, take some time for yourself in another room or go outside. Use the resources mentioned in this article to get support digitally. If this does not suffice, please reach out for professional help. Supports may be in place from local universities, the American Medical Association, and state and local professional societies. Limiting your news and social media consumption that you find upsetting may also reduce stress. Avoid using alcohol and other drugs to deal with your emotions—instead, use the skills that have enabled you to get through difficult situations in the past.62 Practicing compassion with yourself and others is also helpful.63 Initiating a gratitude practice has been shown to improve a sense of connection, quality, and amount of sleep and has improved well-being.64 This can be achieved through a gratitude journal in which you write daily entries about someone or something you are grateful for or listing 3 good things daily, which has been shown to reduce symptoms of depression and improve well-being.65 Engaging in a religious or spirituality practice has been associated with improved coping, strategies of acceptance, and less burnout in internal medicine and pediatric interns.66 Finally, allowing time to debrief, meditate, or discuss challenging situations and grief can be helpful to prevent burnout.67

Governmental and health care agencies, institutions, and professional societies can help by sharing and continually updating information and resources. Communication that is concise, clear, transparent, timely, and thoughtful will help build a sense of control in health care providers.13 Data from the H1N1 pandemic revealed that sufficiency of information was associated with reduced worry.68 Freeing providers from administrative tasks will allow peak performance for longer periods of time. Leadership should encourage all providers to strive to live the tenets of physician wellness.13

Conclusions

“World War V” is clearly upon us, with all the attendant anxieties and disruptions one might imagine when fighting an invisible enemy on home turf.69 We are faced with a new reality that has changed our culture, implicit assumptions, and basic underpinnings of our daily work. Mandated “stay-at-home” orders and self-quarantine social norms seem to have arrived overnight in some areas of the country, but a patchwork of inconsistency adds to a dizzying assessment of risk—and if we as medical experts find ourselves occasionally off balance, it is certain that our patients likely feel the same.

Clinician wellness can be an overlooked and marginalized aspect of our lives. In the daily hustle, self-care may often be a last priority as we continue to practice in a field of self-sacrifice and service to others. But if we do not realize it in the beginning, we will certainly realize it in the end that without self-care we will have nothing left to offer to anyone. The caregiver must take care of himself or herself if they want to do a good job taking care of others.

COVID-19 has arrived, and life is different. As we realize that we are in a seminal moment, that future generations may refer to “pre-COVID” and “post-COVID,”69 we must also pause to reflect, to breathe, and to care for ourselves and our loved ones. This COVID-19 pandemic will pass, and although SARS-CoV-2 may see a slow burn with seasonal encores in the next several years, the practice of allergy and immunology will continue to provide critical services, even as our infrastructure is temporarily reorganized during social distancing. As a specialty, allergy and immunology will continue to lead, and as our community comes together, we will persevere. Take care of yourself.

Footnotes

M.G. is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant no. 5K08HS024599-02).

Conflicts of interest: P. Bansal has served on the advisory boards for Genentech, Regeneron, Kaleo, AstraZeneca, ALK, Shire, Takeda, Pharming, CSL Behring, and Teva; has served as a speaker for AstraZeneca, Regeneron, ALK, Takeda, Shire, CSL Behring, Takeda, and Pharming; and has served as an independent consultant for ALK, AstraZeneca, and Exhale. M. Greenhawt is supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (grant no. 5K08HS024599-02); is an expert panel and coordinating committee member of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases–sponsored Guidelines for Peanut Allergy Prevention; has served as a consultant for the Canadian Transportation Agency, Thermo Fisher, Intrommune, and Aimmune Therapeutics; is a member of physician/medical advisory boards for Aimmune Therapeutics, DBV Technologies, Sanofi/Genzyme, Genentech, GlaxoSmithKline, Merck, Nutricia, Kaleo Pharmaceutical, Nestle, Acquestive, Allergy Therapeutics, Allergenis, Aravax, and Monsanto; is a member of the Scientific Advisory Council for the National Peanut Board; has received honorarium for lectures from Thermo Fisher, Aimmune Therapeutics, DBV Technologies, Before Brands, multiple state allergy societies, the American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, and the European Academy of Allergy and Clinical Immunology; is an associate editor for the Annals of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology; and is a member of the Joint Taskforce on Allergy Practice Parameters. G. Mosnaim has received research grant support from AstraZeneca and GlaxoSmithKline; currently receives research grant support from Propeller Health; owned stock in Electrocore; and served as a consultant and/or member of a scientific advisory board for GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi-Regeneron, Teva, Novartis, AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, and Propeller Health. J. Oppenheimer has served as a consultant for AstraZeneca, GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi, and Novartis; is a consultant for GlaxoSmithKline, AstraZeneca, and Sanofi; is Associate Editor for Annals of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology and AllergyWatch; is Section Editor of Current Opinion of Allergy; receives royalties from Up to Date; is Board Liaison American Board of Internal Medicine for American Board of Allergy and Immunology; and is a member of the Joint Taskforce on Allergy Practice Parameters. D. Stukus is a consultant for DBV Therapeutics, Before Brands, and Abbott Nutrition. M. Shaker has a brother who is CEO of Altrix Medical; is a member of the Joint Task force on Practice Parameters; and serves on the editorial boards of the Journal of Allergy and Clinical Immunology: In Practice, Annals of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology, and the Journal of Food Allergy. The rest of the authors declare that they have no relevant conflicts of interest.

Online Repository. Pandemic Social Media and the Allergist/Immunologist

During these stressful times, medical professionals can use social media to benefit themselves as well as their patients. In addition to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, trusted medical organizations such as the American Academy of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology (AAAAI), the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases, and the World Health Organization can be accessed for resources to help clinicians prepare but can also be used to curate and share information with others as well. Clinicians should embrace the trusted relationships they have developed with their own patients as well as the desire of the general public and media to hear from experts.E1 Those already active on social media can serve as a valuable resource to provide perspective, general information, and address misinformation. One example of conflicting reports from mainstream media that have circulated on social media during the COVID-19 pandemic involves confusion regarding the risk of using corticosteroids during active infection, a topic that is pertinent to patients with asthma. In this example, professionals can use their role on social media to provide anticipatory guidance to patients with asthma by reinforcing the need to maintain inhaled corticosteroid controller medications to try and prevent exacerbations, and highlighting the importance of understanding when and how to start treatment should symptoms occur. In an online world filled with misinformation and fear mongering, clinicians can use their social media presence to promote preparedness, encourage positive behavior change, and spread accurate information instead of panic.E2 Medical professionals who are not active on social media can still use these platforms to better understand the common questions or points of confusion being discussed. This can aid anticipatory guidance with individual patients who may not raise these concerns on their own during clinical encounters, or provide resources on practice Web sites addressing frequently asked questions.

It is also important for clinicians to recognize how their use of social media may impact their well-being. In addition, clinicians can seek out social media groups that provide professional and emotional support.E3, E4 There are countless examples of online groups that provide comfort and collegiality, which can be extremely important for those in community-based outpatient practices who may have limited interactions with colleagues and those who may have temporarily closed their practices because of the current social distancing guidelines. The Physicians Moms Group on Facebook is one of the more prominent examples, where more than 70,000 women share personal and professional stories with one another in a closed forum. Now more than ever, it is important for all of us to be mindful of our social media habits, recognize when our online interactions encroach upon our well-being, and use social media in a positive manner.

Wellness at Work

Telehealth can minimize risk and promote safety, and newly developed AAAAI resources exist to help the clinician get started.E5, E6, E7 Creating a practice task force to assess recommendations from local, state, and federal governments, as well as medical societies, can be helpful at the onset.E8 Obtaining PPE is essential, although challenging in the current rationed environment. In addition, collaborating with other local allergists and immunologists can facilitate idea exchange and highlight the reality that, even at a social distance, we are not alone.E8 Engaging the health care team at the beginning of a workday will help to prevent many stressful situations and also help to lay a scaffold to quickly resolve problems that do arise.E9 At this time, social distancing is critical to mitigating COVID-19, as is routine and increased office and equipment cleaning.E10

From the business standpoint, cross-training employees and preparing for increased absenteeism is necessary.E10 Reviewing practice finances including cash flow and having a plan for decreased income due to potentially less numbers of patients and procedures is necessary, and it is hoped that recent federal legislation will provide some respite.E10 Specifically, the Coronavirus Aid, Relief, and Economic Security (CARES) Act of 2020, passed in the Senate with bipartisan support on March 25, 2020, may provide more than $2 trillion in total relief and $350 billion in support for small businesses.E11 It is important to remember that some allergists and immunologists may temporarily suspend in-office operations or provide care almost exclusively by telehealth, depending on various individual factors, including personal and professional. Preparing for this possibility is advisable.E8

Regarding patient care, overcommunication is preferred.E8 Postponing nonessential appointments or procedures is recommended and necessary for social distancing to be effective; however, patient-specific decisions should still be determined by the individual clinician's clinical judgment.E8, E12 Patients may be more or less concerned about the COVID-19 pandemic than their clinicians, and may be receiving information (and misinformation) from various sources. Reinforcing the concept of social distancing as well as the importance of adequate sleep, exercise (with social distance in mind), and diet is sound advice. Discussing the ways in which the practice is adapting care in the COVID-19 pandemic era includes active communication methods such as Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act secure text messaging and email software; social media updates via platforms such as Facebook, Twitter, and Instagram; consistently updating the practice website; and placing well-marked educational signage. These interventions can help alleviate patient concerns. Of note, avoidance of stigmatizing groups of people due to suspected or actual infection is fundamental.E13 , E14

Cost-Effectiveness of Clinician Wellness

The effect of clinician wellness and wellness programs may be life-changing and life-saving. Unfortunately, even outside of a pandemic the risk of burnout and consequences of ignoring aspects of wellness are underappreciated and often undervalued. Although cost-effectiveness analyses can be a useful analytical tool to understand whether financial trade-offs are worth gains in quality of life, the health and economic consequences of ignoring personal wellness in the practice of medicine have not been well studied.

In the Medscape 2019 physician compensation report, primary care providers earned an average of $237K per year and average annual specialist compensation was $341K.E15 In this report of 19,328 respondents across 30+ specialties, annual compensation for allergy and immunology was $274K. Although physicians spent an average of 37 to 40 hours in patient care, 36% of respondents spent 20 hours or more on paperwork and administration per week.E15 This represents a dramatic increase from 2012, where 53% of physicians spent about 1 to 4 hours on paperwork.E15 Although most felt rewarded by either patient relationships, problem solving, or making the world a better place, 2% of physicians reported that nothing about their job was rewarding.E15 Seventy-three percent of allergy and immunology physicians would choose medicine again, with 82% of those preferring to remain in their chosen field of practice.E15

To illustrate the potential cost-effectiveness of clinician wellness, we constructed a simple Markov model evaluating a cohort of physicians earning the mean salary for allergy and immunology, working 40 hours per week in direct patient care, with 10 hours per week spent on administrative tasks.E16 Although the health state utility of wellness is unknown, we explored plausible disutility (eg, negative health detriment from an action) ranges of 1% to 5% compared with an idealized practice of work-life balance over a 30-year model horizon, starting practice at age 30 years. Future costs and utilities were uniformly discounted at 3% per annum, with all-cause age-adjusted mortality incorporated into the model and 1-year cycle length.E17, E18

When considering medical practice, cost-effective care is defined as care costing less than $100,000/quality-adjusted life-year (QALY), with a QALY measured by the relative trade-off between a perfect year of wellness and challenges associated with burnout resulting from inattention to personal wellness.E16 In this wellness model, a 1% equal reduction in health state utility and compensation demonstrated cost-effectiveness of wellness of $269,440 per QALY, a 10% disutilty with 5% compensation reduction cost $137,469 per QALY, whereas a 15% health disutility with 5% compensation reduction cost $91,646 per QALY. At a 20% relative disutility of wellness, a 5% reduction in compensation cost $68,735 per QALY. Findings from the physician cost-effectiveness wellness model confirmed that attention to wellness can be a cost-effective prospect, even if requiring a reduction in compensation.

COVID-19 Allergy Society Supports

The North American allergy and immunology professional societies—the AAAAI, the American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, and the Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology—are providing real-time resources to help on-the-ground clinicians navigate the COVID-19 pandemic. Although challenges to allergists/immunologists vary contextually by private, hospital, or academic practice, societal leadership and collegial support is crucial. These organizations are uniquely positioned to provide resources for contingency planning, advocacy, education, and research priorities during these challenging times. Recently, the AAAAI, the American College of Allergy, Asthma & Immunology, and the Canadian Society of Allergy and Clinical Immunology endorsed a framework for COVID-19 contingency planning in the allergy and immunology clinics in addition to distributing and/or promoting videos, podcasts, social media outreach, community forums, and virtual journal club.E19 Through leveraging global health expertise, these allergy societies have taken action, such as mobilizing a COVID-19 Task Force charged with real-time monitoring of a fluid and ever-changing pandemic and initiating rapid response communication of critical information. During this time, coordinated messaging from North American allergy and immunology societies can play a pivotal role in advocacy at the federal and state levels to address issues such as expanding coverage for telehealth services nationwide and mitigating the financial impact of the pandemic on private practices.E20, E21, E22

How New Strategies and Novel Paradigms of Care Delivery Can Help

Allergy/Immunology clinic contingency planning can allow for compliance with local and state regulations being increasingly required to defer nonessential medical services during shelter-in-place mandates.E19 Through this pandemic the ability to persevere will both require and nourish resilience—a key wellness tool.

The rapid adoption of telehealth is a critical component of COVID-19 care. Without a doubt, the advent of telehealth in the past few years will be a saving grace, and the rapid incorporation of this service into daily practice will no doubt be a lasting legacy of COVID-19. Although it is not always a perfect surrogate for an in-office visit, when viewing the current situation as temporary, it may allow most care to resume without too much interruption outside of certain parts of the physical examination and certain procedures. Many regulations regarding telehealth have been relaxed during the pandemic, allowing for practice across state lines without having to have a license in that state, with use of less HIPPA-compliant vehicles for communication, and ensuring that video visits can be reimbursed at the same level as an in-office visit for the same issue.E6, E7, E23 Telehealth services can also provide access to aspects of care unavailable with in-person visits, such as creating the avenue for virtual home-visits and, despite social distancing, providing a different view into patient and family needs in the more personal context of their own home. Telehealth may also create conversations with multiple family members to better inform practice—individuals who can inform care and help to promote adherence in ways that may not happen with conventional visits.E7

An added telehealth benefit may also be improved overall productivity from individual clinicians as well.E24 Following the pandemic, the ability to conserve some of the more relaxed telehealth standards could be of significant benefit to expanding the reach of a practice into lesser served areas as well.E25 This crisis will certainly foster creativity in rethinking the way that we deliver care and provide an opportunity to do things better for our patients. There are a few practical examples of this. Economic models have been previously published that have noted the safety of home biologic agent administration,E26 lack of necessity to activate emergency medical services and seek emergency care after using epinephrine if the patient stabilizes,E27 and the necessity for screening even high-risk infants for early peanut introduction under the National Institute of Allergy and Immunological Diseases guidelines.E28, E29 A better understanding of what services prove essential, where patient preferences may leverage shared decision making,E30 and what aspects of care can be reduced or shifted from an in-office to a telehealth or at-home platform will maximize health and economic outcomes of care during the pandemic. These approaches will allow our specialty to better focus on increasing the value of the care we provide and expand the access to that care.

References

- 1.Del Rio C., Malani P.N. COVID-19—new insights on a rapidly changing epidemic. JAMA. 2020;323:1339–1340. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3072. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) situation summary. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/index.html Available from: Accessed March 28, 2020.

- 3.Wu Z., McGoogan J.M. Characteristics of and important lessons from the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in China: summary of a report of 72 314 cases from the Chinese Center for Disease Control and Prevention. JAMA. 2020;323:1239–1242. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.2648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Shaker M.S., Oppenheimer J., Grayson M., Stukus D., Hartog N., Hsieh E., et al. COVID-19: pandemic contingency planning for the allergy and immunology clinic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:1477–1488.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Livingston E., Bucher K. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) in Italy. JAMA. 2020;323:1335. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.4344. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Remuzzi A., Remuzzi G. COVID-19 and Italy: what next? Lancet. 2020;395:1225–1228. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30627-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shaker M., Hsu-Blatman K., Abrams M. E. Engaging patient partners in state of the art allergy care: finding balance when discussing risk [published online ahead of print February 7, 2020] Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 8.Geldsetzer P. Knowledge and perceptions of COVID-19 among the general public in the United States and the United Kingdom: a cross-sectional online survey [published online ahead of print March 20, 2020] Ann Intern Med. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.PubMed. COVID-19 search results. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/?term=COVID-19 Available from: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 10.Johns Hopkins University & Medicine. Coronavirus Resource Center. https://coronavirus.jhu.edu Available from: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 11.A fiasco in the making? As the coronavirus pandemic takes hold, we are making decisions without reliable data. https://www.statnews.com/2020/03/17/a-fiasco-in-the-making-as-the-coronavirus-pandemic-takes-hold-we-are-making-decisions-without-reliable-data/ Available from: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 12.Slisco A. More than 50 doctors in Italy have now died from coronavirus. Newsweek. March 27, 2020. https://www.newsweek.com/more-50-doctors-italy-have-now-died-coronavirus-1494781 Available from: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 13.Adams J.G., Walls R.M. Supporting the health care workforce during the COVID-19 global epidemic. JAMA. 2020;323:1439–1440. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.3972. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.NHS Improvement Lens of profound knowledge. https://improvement.nhs.uk/documents/2127/lens-profound-knowledge.pdf Available from: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 15.Nanda A., Wasan A., Sussman J. Provider health and wellness. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;56:1543–1548. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Shanafelt T.D., Boone S., Tan L., Dyrbye L.N., Sotile W., Satele D., et al. Burnout and satisfaction with work-life balance among US physicians relative to the general US population. Arch Intern Med. 2012;172:1377–1385. doi: 10.1001/archinternmed.2012.3199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gabbe S.G., Melville J., Mandel L., Walker E. Burnout in chairs of obstetrics and gynecology: diagnosis, treatment, and prevention. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:601–612. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.122391. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bingemann T., Sharma H., Nanda A., Khan D.A., Markovics S., Sussman J., et al. AAAAI Work Group Report: Physician Wellness in Allergy and Immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:1224–1229. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.01.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nedrow A., Steckler N.A., Hardman J. Physician resilience and burnout: can you make the switch? Fam Pract Manag. 2013;20:25–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Shanafelt T.D., Dyrbye L.N., West C.P. Addressing physician burnout: the way forward. JAMA. 2017;317:901–902. doi: 10.1001/jama.2017.0076. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Federation of State Physician Health Programs. State programs. https://www.fsphp.org/state-programs Available from: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 22.American Medical Association AMA code of medical ethics: guidance in a pandemic. https://www.ama-assn.org/delivering-care/ethics/ama-code-medical-ethics-guidance-pandemic Available from: Accessed March 30, 2020.

- 23.State of New York Executive Order Continuing temporary suspension and modification of laws relating to the disaster emergency. https://www.governor.ny.gov/sites/governor.ny.gov/files/atoms/files/EO_202.12.pdf Available from: Accessed March 30, 2020.

- 24.Kübler-Ross E. MacMillian; New York, NY: 1969. On death and dying. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Maciejewski P.K., Zhang B., Block S.D., Prigerson H.G. An empirical examination of the stage theory of grief. JAMA. 2007;297:716–723. doi: 10.1001/jama.297.7.716. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Shampo M.A., Kyle R.A., Steensma D.P. L. E. Trudeau—founder of a sanatorium for treatment of tuberculosis. Mayo Clin Proc. 2010;85:e48. doi: 10.4065/mcp.2010.0379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hawes J., Stone M. Collapse therapy of pulmonary tuberculosis in New England States. JAMA. 1932;98:2048–2051. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Corbetta L., Tofani A., Montinaro F. Lobar collapse therapy using endobronchial valves as a new complementary approach to treat cavities in multidrug-resistant tuberculosis and difficult-to-treat tuberculosis: a case series. Respiration. 2016;92:316–328. doi: 10.1159/000450757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Schatz A., Bugie E., Waksman S. Streptomycin, a substance exhibiting antibiotic activity against Gram positive and Gram negative bacteria. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1944;55:66–69. doi: 10.1097/01.blo.0000175887.98112.fe. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Mathieu E. The Internet and medical decision making: can it replace the role of health care providers? Med Decis Making. 2010;30:14S–16S. doi: 10.1177/0272989X10381228. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lazer D.M.J., Baum M.A., Benkler Y., Berinsky A.J., Greenhill K.M., Menczer F., et al. The science of fake news. Science. 2018;359:1094–1096. doi: 10.1126/science.aao2998. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Weinstein A., Lejoyeux M. Internet addiction or excessive internet use. Am J Drug Alcohol Abuse. 2010;36:277–283. doi: 10.3109/00952990.2010.491880. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Rotenstein L.S., Ramos M.A., Torre M., Segal J.B., Peluso M.J., Guille C., et al. Prevalence of depression, depressive symptoms, and suicidal ideation among medical students: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;316:2214–2236. doi: 10.1001/jama.2016.17324. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mata D.A., Ramos M.A., Bansal N., Khan R., Guille C., Di Angelantonio E., et al. Prevalence of depression and depressive symptoms among resident physicians: a systematic review and meta-analysis. JAMA. 2015;314:2373–2383. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.15845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kane L. Medscape national physician burnout and suicide report 2020: the generational divide. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2020-lifestyle-burnout-6012460 Available from: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 36.Schernhammer E. Taking their own lives -- the high rate of physician suicide. N Engl J Med. 2005;352:2473–2476. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp058014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Hampton T. Experts address risk of physician suicide. JAMA. 2005;294:1189–1191. doi: 10.1001/jama.294.10.1189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Lai J., Ma S., Wang Y., Cai Z., Hu J., Wei N., et al. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e203976. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Nanda A., Moore A. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) with a focus on older adults: a guide for allergists and immunologists and patients. 2020. https://education.aaaai.org/resources-for-a-i-clinicians/olderadults_covid-19 Available from: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 40.Lumry W., Davis C., Nanda A. Texas Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology Society statement on Gov. Abbott's executive order GA-09. https://taais.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/COVID-19-Document-03252020-Final.pdf Available from: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 41.American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology Use of telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://education.aaaai.org/resources-for-a-i-clinicians/telemedicine_covid-19 Available from: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 42.American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology AAAAI telemedicine toolkit. https://www.aaaai.org/practice-resources/running-your-practice/practice-management-resources/telemedicine Available from: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 43.Shute D.A. 7 tips for running your practice in the coronavirus crisis. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/927319 Available from: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 44.American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology COVID-19: pandemic. Small business resources. https://www.aaaai.org/about-aaaai/advocacy/covid Available from: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 45.Foster B.L. How to master working from home—while under quarantine with kids. Parents. 2020. https://www.parents.com/parenting/work/life-balance/how-to-master-being-a-work-at-home-mom/ Available from: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 46.Hare K. How to work from home with kids around. Poynter. March 13, 2020. https://www.poynter.org/business-work/2020/how-to-work-from-home-with-kids-around Available from: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 47.Bahney A. How to work from home with kids (without losing it). CNN Business. March 17, 2020. https://www.cnn.com/2020/03/16/success/working-from-home-with-kids-coronavirus/index.html Available from: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- 48.Chan C.L., Chan T.H., Ng S.M. The Strength-Focused and Meaning-Oriented Approach to Resilience and Transformation (SMART): a body-mind-spirit approach to trauma management. Soc Work Health Care. 2006;43:9–36. doi: 10.1300/J010v43n02_03. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Pospos S., Young I.T., Downs N., Iglewicz A., Depp C., Chen J.Y., et al. Web-based tools and mobile applications to mitigate burnout, depression, and suicidality among healthcare students and professionals: a systematic review. Acad Psychiatry. 2018;421:109–120. doi: 10.1007/s40596-017-0868-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.American Psychiatric Association App evaluation model. https://www.psychiatry.org/psychiatrists/practice/mental-health-apps/app-evaluation-model Available from: Accessed March 28, 2020.

- 51.Guille C., Zhao Z., Krystal J., Nichols B., Brady K., Sen S. Web-based cognitive behavioral therapy intervention for the prevention of suicidal ideation in medical interns: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Psychiatry. 2015;72:1192–1198. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2015.1880. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Ho C.S., Chee C.Y., Ho R.C. Mental health strategies to combat the psychological impact of COVID-19 beyond paranoia and panic. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2020;49:1–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology Physician wellness toolkit. https://www.aaaai.org/practice-resources/running-your-practice/practice-management-resources/wellness Available from: Accessed March 28, 2020.

- 54.American Medical Association AMA steps forward. https://edhub.ama-assn.org/steps-forward Available from: Accessed March 28, 2020.

- 55.Stanford Medicine WellMD. https://wellmd.stanford.edu Available from: Accessed March 28, 2020.

- 56.Institute for Healthcare Improvement. COVID-19 guidance and resources. http://www.ihi.org/Topics/COVID-19/Pages/default.aspx Available from: Accessed March 28, 2020.

- 57.Alliance for Academic Internal Medicine Wellness and resiliency: CHARM. https://www.im.org/resources/wellness-resiliency/charm Available from: Accessed March 28, 2020.

- 58.The Art of Living. Online wellness program. https://event.us.artofliving.org/us-en/hcp-online-wellness-program/ Available from: Accessed April 14, 2020.

- 59.Headspace. We're here for you. https://www.headspace.com/covid-19 Available from: Accessed March 28, 2020.

- 60.Ten Percent Happier Coronavirus sanity guide. https://www.tenpercent.com/coronavirussanityguide Available from: Accessed March 28, 2020.

- 61.University of Rochester Make every effort to connect digitally with other people. March 25, 2020. https://www.rochester.edu/newscenter/how-to-cope-with-psychology-of-social-distancing-420922/ Available from: Accessed March 28, 2020.

- 62.World Health Organization Coping with stress during the 2019-nCoV outbreak. 2020. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/coping-with-stress.pdf?sfvrsn=9845bc3a_2 Available from: Accessed March 28, 2020.

- 63.The Schwartz Center. Resources for healthcare professionals coping with the COVID-19 pandemic. 2020. https://www.theschwartzcenter.org/covid-19 Available from: Accessed March 28, 2020.

- 64.Emmons R.A., McCullough M.E. Counting blessings versus burdens: an experimental investigation of gratitude and subjective well-being in daily life. J Pers Soc Psychol. 2003;84:377–389. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.84.2.377. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Rippstein-Leuenberger K., Mauthner O., Bryan Sexton J., Schwendimann R. A qualitative analysis of the Three Good Things intervention in healthcare workers. BMJ Open. 2017;7:e015826. doi: 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-015826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Doolittle B.R., Windish D.M. Correlation of burnout syndrome with specific coping strategies, behaviors, and spiritual attitudes among interns at Yale University, New Haven, USA. J Educ Eval Health Prof. 2015;12:41. doi: 10.3352/jeehp.2015.12.41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Gogo A., Osta A., McClafferty H., Rana D.T. Cultivating a way of being and doing: individual strategies for physician well-being and resilience. Curr Probl Pediatr Adolesc Health Care. 2019;49:100663. doi: 10.1016/j.cppeds.2019.100663. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Goulia P., Mantas C., Dimitroula D., Mantis D., Hyphantis T. General hospital staff worries, perceived sufficiency of information and associated psychological distress during the A/H1N1 influenza pandemic. BMC Infect Dis. 2010;10:322. doi: 10.1186/1471-2334-10-322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.McLuhan A. World War “V”. The American Mind. March 16, 2020. https://americanmind.org/features/the-coronacrisis-and-our-future-discontents/world-war-v/ Available from: Accessed March 29, 2020.

References

- Stukus D.R. How Dr Google is impacting parental medical decision making. Immunol Allergy Clin North Am. 2019;39:583–591. doi: 10.1016/j.iac.2019.07.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kind T., Greysen S.R., Chretien K.C. Advantages and challenges of social media in pediatrics. Pediatr Ann. 2011;40:430–434. doi: 10.3928/00904481-20110815-05. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chan W.S., Leung A.Y. Use of social network sites for communication among health professionals: systematic review. J Med Internet Res. 2018;20:e117. doi: 10.2196/jmir.8382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolls K., Hansen M., Jackson D., Elliott D. How health care professionals use social media to create virtual communities: an integrative review. J Med Internet Res. 2016;18:e166. doi: 10.2196/jmir.5312. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology AAAAI telemedicine toolkit. https://www.aaaai.org/practice-resources/running-your-practice/practice-management-resources/telemedicine Available from: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology Use of telemedicine during the COVID-19 pandemic. Resources for A/I clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://education.aaaai.org/resources-for-a-i-clinicians/covid-19 Available from: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- Portnoy J., Waller M., Elliot T. Telemedicine in the era of COVID-19. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:1489–1491. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.03.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shute D.A. 7 tips for running your practice in the coronavirus crisis. https://www.medscape.com/viewarticle/927319 Available from: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- Nanda A., Wasan A., Sussman J. Provider health and wellness. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2017;5:1543–1548. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2017.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology. Small business resources. https://www.aaaai.org/about-aaaai/advocacy/covid Available from: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- Current economic relief opportunities for US small business impacted by the COVID-19 outbreak in the CARES Act. National Law Review. March 26, 2020. https://www.natlawreview.com/article/current-economic-relief-opportunities-us-small-businesses-impacted-covid-19-outbreak Available from: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- Lumry W., Davis C., Nanda A. Texas Allergy, Asthma, and Immunology Society statement on Gov. Abbott's executive order GA-09. https://taais.org/wp-content/uploads/2020/03/COVID-19-Document-03252020-Final.pdf Available from: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Reducing stigma. https://www.cdc.gov/coronavirus/2019-ncov/daily-life-coping/reducing-stigma.html Available from: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- Nanda A., Moore A. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) with a focus on older adults: a guide for allergists and immunologists and patients. https://education.aaaai.org/resources-for-a-i-clinicians/olderadults_covid-19 Available from: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- Kane L. Medscape physician compensation report. 2019. https://www.medscape.com/slideshow/2019-compensation-overview-6011286 Available from: Accessed March 27, 2020.

- Shaker M., Greenhawt M. A primer on cost-effectiveness in the allergy clinic. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;123:120–128.e1. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2019.05.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- US Department of Labor, Bureau of Labor Statistics. March 22, 2020. https://www.bls.gov/ Available from: Accessed March 22, 2020.

- Arias E., Xu J. United States Life Tables, 2015. Natl Vital Stat Rep. 2018;67:1–63. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaker M.S., Oppenheimer J., Grayson M., Stukus D., Hartog N., Hsieh E., et al. COVID-19: pandemic contingency planning for the allergy and immunology clinic. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:1477–1488.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2020.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Academy of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology Resources for A/I clinicians during the COVID-19 pandemic. https://education.aaaai.org/resources-for-a-i-clinicians/covid-19 Available from: Accessed March 29, 2020.

- American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology Coronavirus (COVID-19) resources. https://education.acaai.org/coronavirus Available from: Accessed March 29, 2020.

- Canadian Society for Allergy and Clinical Immunology. https://csaci.ca Available from: Accessed March 29, 2020.

- American College of Allergy, Asthma, & Immunology. Telehealth toolkit. https://college.acaai.org/practice-management/telehealth-toolkit Available from: Accessed March 29, 2020.

- Portnoy J.M., Waller M., De Lurgio S., Dinakar C. Telemedicine is as effective as in-person visits for patients with asthma. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2016;117:241–245. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2016.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Portnoy J.M., Pandya A., Waller M., Elliott T. Telemedicine and emerging technologies for health care in allergy/immunology. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2020;145:445–454. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2019.12.903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaker M., Briggs A., Dbouk A., Dutille E., Oppenheimer J., Greenhawt M. Estimation of health and economic benefits of clinic versus home administration of omalizumab and mepolizumab. J Allergy Clin Immunol Pract. 2020;8:565–572. doi: 10.1016/j.jaip.2019.09.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaker M., Kanaoka T., Feenan L., Greenhawt M. An economic evaluation of immediate vs non-immediate activation of emergency medical services after epinephrine use for peanut-induced anaphylaxis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2019;1221:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.anai.2018.06.035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaker M., Stukus D., Chan E.S., Fleischer D.M., Spergel J.M., Greenhawt M. “To screen or not to screen”: comparing the health and economic benefits of early peanut introduction strategies in five countries. Allergy. 2018;73:1707–1714. doi: 10.1111/all.13446. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhawt M., Shaker M. Determining levers of cost-effectiveness for screening infants at high risk for peanut sensitization before early peanut introduction. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:e1918041. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.18041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Greenhawt M., Shaker M., Winders T., Bukstein D.A., Davis R.S., Oppenheimer J., et al. Development and acceptability of a shared decision-making tool for commercial peanut allergy therapies [published online ahead of print February 11, 2020] Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. [DOI] [PubMed]