Abstract

In association with the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), anti-inflammatory response syndrome is commonly manifested in patients with trauma, burn injury, and after major surgery. These patients are increasingly susceptible to infection with various pathogens due to the excessive release of anti-inflammatory cytokines from anti-inflammatory effector cells. Recently, CC-chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) found in the sera of mice with pancreatitis was identified as an active molecule for SIRS-associated anti-inflammatory response manifestation. Also, the inhibitory activity of glycyrrhizin (GL) on CCL2 production was reported. Therefore, the effect of GL on SIRS-associated anti-inflammatory response manifestation was investigated in a murine SIRS model. Without any stimulation, splenic T cells from mice 5 days after SIRS induction produced cytokines associated with anti-inflammatory response manifestation. However, these cytokines were not produced by splenic T cells from SIRS mice previously treated with GL. In dual-chamber transwells, IL-4-producing cells were generated from normal T cells cultured with peripheral blood polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN) from SIRS mice. However, IL-4-producing cells were not generated from normal T cells in transwell cultures performed with PMN from GL-treated SIRS mice. CCL2 was produced by PMN from SIRS mice, while this chemokine was not demonstrated in cultures of PMN from SIRS mice treated with GL. These results indicate that GL has the capacity to suppress SIRS-associated anti-inflammatory response manifestation through the inhibition of CCL2 production by PMN.

Keywords: CCL2, IL-4, Systemic inflammatory response syndrome, Glycyrrhizin, Neutrophils

1. Introduction

The systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) frequently develops in patients with polytrauma, severe burn injury, and after major surgery [1]. SIRS is a systemic inflammatory reaction developed from local inflammatory responses against injured tissues or a local infection [1]. Infections demonstrated in patients with SIRS are classified as sepsis [1]. Severe SIRS is accompanied by multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS), ultimately leading to multiple organ failure (MOF), resulting in death [1]. Therefore, the clinical course of patients with polytrauma, severe burn injury, and after major surgery appears strongly associated with the manifestations of SIRS [2], [3], [4], [5]. The overwhelming systemic pro-inflammatory reaction caused by SIRS leads to an overactive anti-inflammatory response [6]. Anti-inflammatory response appears to regulate the inflammatory responses during SIRS [6]. Anti-inflammatory response appeared in association with SIRS is defined as impaired HLA-DR expression (less than 30% as compared to healthy controls) and an increase in the plasma concentration of Th2 cytokines (IL-4, IL-10, and IL-13) [7], [8], [9]. The susceptibility of patients with SIRS-associated anti-inflammatory response to infections increases greatly due to Th2 cytokine-associated immunosuppression [7], [8], [9]. Previously, we have demonstrated how SIRS decreases the host’s anti-bacterial resistance [10]. Mice with severe pancreatitis (a murine model of representative SIRS) were susceptible to sepsis induced by cecal ligation and puncture (CLP) [11]. In addition, CC chemokine ligand 2 (CCL2) in the circulation has been shown to contribute to the increased susceptibility of these mice to CLP-induced sepsis [12].

Glycyrrhizin (GL), an extract from licorice roots with a structure of 20β-carboxy-11-oxo-30-norolean-12-en-3β-yl-2-O-β-d-glucopyranuronosyl-a-d-glucopyranosiduronic acid [13], has been described to inhibit inflammation, augment natural killer cell activity, and induce IFN-γ production [14]. In Japan, GL has been used clinically for more than 20 years in patients with chronic hepatitis [13], [14]. GL has an antiviral activity against human cytomegalovirus [15], herpes simplex virus type 2 [16], influenza virus [17], HIV [18], [19], [20], and coronavirus [21]. Recently, GL has been described as an inhibitor of CCL2 production in cultures of human monocytes infected with M-tropic HIV [22]. Therefore, in this study the regulatory effect of GL on SIRS-associated anti-inflammatory response manifestation was investigated in a mouse model of SIRS. In this study, we chose to use the term “SIRS” for the SIRS-like syndrome in mice, although the strict definition of SIRS as applied in humans cannot be applied in animals. The results show that GL down-regulates SIRS-associated anti-inflammatory response manifestations through the inhibition of CCL2 production by polymorphonuclear neutrophils (PMN).

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Mice

Eight- to nine-week-old BALB/c mice (The Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME) were used in these experiments. Experimental protocols for animal studies were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of the University of Texas Medical Branch at Galveston (IACUC approval number: 01-04-010).

2.2. Reagents, cells, and media

Monoclonal antibodies (mAbs) for TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-4, IL-10, CCL2, CD3, and CD28 were purchased from BD PharMingen (San Diego, CA). Recombinant murine TNF-α, IL-1β, IL-2, IL-4, IL-10, and CCL2 were obtained from PeproTech (Rocky Hill, NJ). T cells were prepared from the spleens of normal or SIRS mice through the use of T cell enrichment columns (R&D Systems), as previously described [23]. The purity of these cells was greater than 96%, as described previously [23]. As previously described, PMN were isolated from whole peripheral blood using Ficoll–Hypaque and dextran sedimentations [24]. Briefly, peripheral blood was withdrawn from the heart of mice with a heparinized syringe. The peripheral blood was centrifuged with Ficoll–Hypaque, and precipitates were obtained as a PMN rich fraction. Then, precipitates were suspended in 1% dextran (T-500, Pharmacia, Piscataway, NJ) and kept for 1 h at room temperature to allow the sedimentation of residual erythrocytes. The resulting PMN fraction was further treated with erythrocyte-lysing kits (R&D Systems) to eliminate small amounts of erythrocytes. The purity of the PMNs obtained was routinely more than 93%, when analyzed by flow cytometry with FITC-conjugated anti-Gr-1 mAb and Write–Giemsa/ALP stainings. Monocytes were not contained in these PMN preparations, when analyzed using PE-conjugated anti-F4/80 mAb (specific for mouse macrophages/monocytes) and a FACScan flow cytometer. For cultivation, various cell preparations were resuspended in RPMI-1640 medium supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (FBS), 2 mM l-glutamine, antibiotics (100 U/ml penicillin and 100 μg/ml streptomycin) (culture medium).

2.3. GL

GL was supplied by Minophagen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd., Tokyo, Japan. For in vivo experiments, GL was dissolved in saline at the appropriate concentrations and 0.5 ml of the solution was administered i.p. to 26 g mice 1 h after SIRS induction. For in vitro experiments, GL was dissolved in culture medium at the appropriate concentrations and 20 μl of each solution was added to cultures of PMN. As reported in many papers [25], [26], [27], the non-cytotoxic properties of GL at a dose of 1 to 200 μg/ml have been reported. In these papers, the cytotoxic effect of GL has been tested against various murine and human cells by (a) trypan blue dye-exclusion test, (b) the proliferative responses of cells stimulated with anti-CD3 mAb or Con A, (c) H-2 class II antigen expression, and (d) interferon production. These results indicate that GL at concentrations of 1–100 μg/ml is not cytotoxic to Mϕ and PMN.

2.4. A murine SIRS model

Mice with pancreatitis were used as a model of representative SIRS [28]. Pancreatitis was produced in mice, according to the previously reported protocol [28]. To induce SIRS, mice were treated with cerulein (50 μg/kg, i.p.) hourly for 6 h in combination with LPS (1.6 mg/kg, i.p.) 5 h after the first injection of cerulein. All mice were alive more than 10 days after SIRS induction. Markedly enhanced damages (edema, inflammatory cell infiltration, hemorrhage, and necrosis) were demonstrated histologically in the pancreas of these mice. Indicators of multiple organ dysfunction (amylase, GPT, and GOT) have been found in the sera of these mice. They also had a decrease in body temperature (<35.5 °C) and WBC count (<2000 mm3).

2.5. Criteria of anti-inflammatory response manifestation

The manifestation of anti-inflammatory response in SIRS mice was evaluated by the appearance of IL-4 and IL-10 in the sera of tested mice. In addition, anti-inflammatory response manifestation was evaluated by the appearance of T cells with the ability to produce IL-4 and IL-10. These cytokines have been shown to be representative cytokines in anti-inflammatory response that appeared in association with SIRS [6].

2.6. Transwell assay

To determine the effect of GL on PMN-associated generation of anti-inflammatory effector cells, PMN from SIRS mice treated with or without GL (10 mg/kg) were cultured with splenic T cells from normal mice in a dual-chamber transwell [29]. Thus, 600 μl of normal T cell suspension (3 × 105 cells/well) was placed into the lower chamber of the transwell (0.4 μm micropores) (Costar, Corning NY). Before cells were added, lower chambers of all the transwells were coated with a mixture of anti-CD3 mAb (0.1 μg/ml) and anti-CD28 mAb (0.25 μg/ml). One hundred microliters of the cell suspension for PMN (3 × 105 cells/well) was placed into the upper chamber of the transwell. Twelve hours later, the upper chamber was removed and cells in the lower chamber were re-cultured for 5 days in the presence of IL-2 (10 ng/ml). Cells were harvested and examined for their abilities to produce IL-4.

2.7. Production and assay for cytokines

Serum specimens from mice various hours after SIRS induction were assayed for TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-4 using ELISA. For CCL2 production, PMN (2 × 106 cells/ml) from mice 3 h after SIRS induction were cultured in the presence or absence of GL ranging from 0.01 to 100 μg/ml for 24 h. For the induction of IL-4 and IL-10, splenic T cells (2 × 106 cells/ml) from mice 5 days after SIRS induction were cultured for 24 h without any stimulation. Culture fluids harvested were assayed for CCL2, IL-4, and IL-10 using ELISA. The detection limit for cytokines and chemokines were between 16 and 38 pg/ml in our ELISA system. Each assay was performed three times.

2.8. Statistical analysis

Data are presented as means ± SD. Comparisons between experimental and control groups were made by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Fisher’s protected least significant difference test. Results were considered statistically significant if a p < 0.05.

3. Results

3.1. Effect of GL on the anti-inflammatory response manifestation in SIRS mice

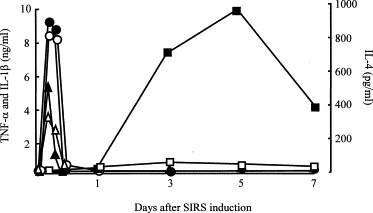

In our previous study [30], normal T cells were converted to Th2 cells (T cells with the ability to produce anti-inflammatory response-related cytokines) in dual-chamber transwells after cultivation with PMN from mice 3 h after SIRS induction. This indicates that soluble factors produced by PMN from mice early after SIRS induction stimulates the subsequent development of anti-inflammatory response. Therefore, the influence of GL on the appearance of soluble factors (SIRS-related cytokines, TNF-α, and IL-1β; anti-inflammatory response-related cytokine, IL-4) in SIRS mice was examined. GL (10 mg/kg) was administered i.p. to mice 1 h after SIRS induction. Serum specimens were prepared from the sera of mice various times after SIRS induction. The amounts of TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-4 in sera were determined using ELISA. Three hours after SIRS induction, TNF-α at a concentration of 9.3 ± 0.4 ng/ml and IL-1β at a concentration of 5.5 ± 0.3 ng/ml were detected in sera. Similar amounts of these cytokines were detected in the sera of mice treated with GL after SIRS induction (Fig. 1 ). Subsequently, these cytokines declined to undetectable levels in the sera of both groups within 12 h of SIRS induction. This indicates that GL did not influence the production of SIRS-related cytokines in SIRS mice.

Fig. 1.

Effect of GL on the production of TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-4 in the sera of mice various times after SIRS induction. Mice were treated with GL (10 mg/kg, i,p., open symbols) or saline (0.2 ml/mouse, i.p., filled symbols) 1 h after SIRS induction. Serum specimens from mice 1, 3, 6, 12, 24 h and 3, 5, 7 days after SIRS induction were assayed for TNF-α (circles), IL-1β (triangles) or IL-4 (squares) using ELISA.

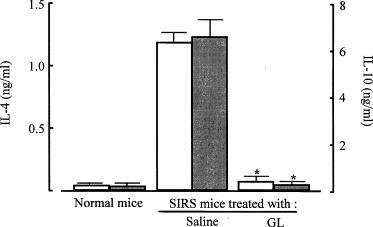

On the other hand, IL-4 was first detected in the sera of mice 3 days after SIRS induction. IL-4 production reached its peak in the 5th day after SIRS induction, and then it gradually declined. However, IL-4 was not detected in the sera of mice treated with GL after SIRS induction (Fig. 1). In addition, the production of IL-4 and IL-10 in vitro by splenic T cells from SIRS mice treated with GL was not demonstrated. Splenic T cells from normal mice did not produce IL-4 and IL-10, while those from mice 5 days after SIRS induction produced these cytokines into their culture fluids. At this time, T cells taken from SIRS mice treated with GL (10 mg/kg) did not produce IL-4 and IL-10 into their culture fluids (Fig. 2 ). These results indicate that GL inhibits SIRS-associated anti-inflammatory response manifestation in SIRS mice.

Fig. 2.

Inhibitory effect of GL on the production of IL-4 and IL-10 by splenic T cells from SIRS mice. Mice were treated with GL (10 mg/kg, i.p.) 1 h after SIRS induction. Splenic T cells (2 × 106 cells/ml) from normal mice and SIRS mice (mice 5 days after SIRS induction) treated with or without GL were cultured for 72 h without any stimulation. Culture fluids were harvested and assayed for IL-4 (open bars) or IL-10 (filled bars) using ELISA. Each result is displayed as means ± SD (n = 5). *p < 0.001 compared with SIRS mice treated with saline.

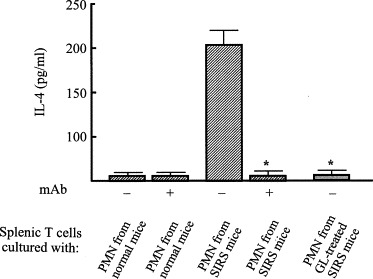

3.2. The inhibitory mechanism of GL on anti-inflammatory response manifestation

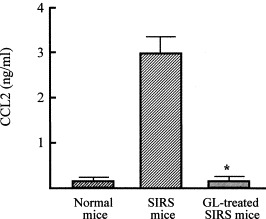

The regulatory mechanism of GL on the manifestation of anti-inflammatory response that appeared in association with SIRS was examined in vitro using a dual-chamber transwell. Splenic T cells (lower chamber) from normal mice were cultured with PMN (upper chamber) from SIRS mice in transwells. According to the results shown in Fig. 1, PMN were obtained from mice 3 h after SIRS induction. The results are shown in Fig. 3 . Normal T cells cultured with PMN from normal mice did not convert to IL-4-producing cells, while normal T cells cultured with PMN from SIRS mice acquired the ability to produce IL-4. At this time, IL-4-producing cells were not demonstrated in transwells cultured with normal T cells and PMN from SIRS mice that were treated with GL. Since CCL2 found in the serum specimens of SIRS mice was identified as an active molecule for SIRS-associated anti-inflammatory response development [30], we next examined CCL2 production in cultures of PMN from SIRS mice treated with or without GL. PMN from SIRS mice produced CCL2 into their culture fluids, but the same cell preparation from normal mice did not (Fig. 4 ). CCL2 production was not demonstrated in culture fluids of PMN from SIRS mice treated with GL. These results indicate that GL inhibits SIRS-associated anti-inflammatory response manifestation by suppressing CCL2 production.

Fig. 3.

IL-4 production by normal T cells in a dual-chamber transwell cultured with PMN from SIRS mice previously treated with GL. SIRS mice were treated with or without GL (10 mg/kg, i.p.) 1 h after SIRS induction. Normal T cells (3 × 105 cells/well, lower chamber) and PMN (2 × 105 cells/well, upper chamber) from SIRS mice were cultured for 24 h in dual-chamber transwells supplemented with anti-CCL2 mAb (10 μg/ml). Cells in the lower chamber were recultured for 5 days and cells harvested were examined for their abilities to produce IL-4. *p < 0.005 compared with untreated SIRS mice.

Fig. 4.

CCL2 production by PMN from SIRS mice treated with or without GL. Mice were treated with or without GL (10 mg/kg, i.p.) 1 h after SIRS induction. PMN (2 × 105 cells/well) from normal mice or these mice were cultured for 48 h and culture fluids harvested were assayed for CCL2. *p < 0.005 compared with untreated SIRS mice.

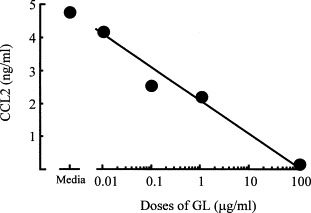

Further, the inhibitory effects of GL on CCL2 production by PMN from SIRS mice were examined in vitro. PMN from mice 3 h after SIRS induction were treated with various doses of GL for 24 h. The amounts of IL-4 in the culture fluids of these cells were determined. Obtained results are shown in Fig. 5 . When PMN from SIRS mice were treated with GL at a dose of 0.1 μg/ml, CCL2 production was inhibited by 50%. GL treatment completely inhibited CCL2 production when 100 μg/ml of GL was added to PMN cultures. These results suggest that GL has the capability to inhibit CCL2 production by PMN from SIRS mice. Through the inhibition of CCL2 production, GL may have the potential to improve anti-inflammatory response manifestation in ill patients with SIRS.

Fig. 5.

Effect of various doses of GL on CCL2 production by PMN from SIRS mice. PMN from SIRS mice were cultured with GL at doses ranging from 0.01 to 100 μg/ml. Culture fluids were harvested 48 h after cultivation and assayed for CCL2.

4. Discussion

As a regulatory mechanism of SIRS, anti-inflammatory response usually appears in response to SIRS development [6]. However, some of the important host defenses against infections are depressed by anti-inflammatory response through the excessive production of IL-4 and IL-10 [7], [8], [9]. Therefore, severe infections are frequently observed in individuals with anti-inflammatory response [7], [8], [9]. Our previous study showed that anti-inflammatory response manifests in SIRS mice in response to CCL2 produced by PMN from SIRS mice [30]. Recently, we have demonstrated that GL has an ability to inhibit CCL2 production by human peripheral blood monocytes infected with HIV [22]. In this study, the effect of GL on SIRS-associated anti-inflammatory response manifestation was investigated in a murine SIRS model. Anti-inflammatory effector cells (splenic T cells acquired the ability to produce IL-4 and IL-10) were generated in mice 5 days after SIRS induction. At this time, IFN-γ production by these T cells was not demonstrated. The production of IL-4 and IL-10 by T cells from SIRS mice was reduced by treatment with GL. However, the production of IFN-γ by T cells from SIRS mice was not influenced by treatment with GL (data not shown). In dual-chamber transwells, T cells from non-SIRS mice (normal T cells) converted to IL-4-producing cells after cultivation with PMN from SIRS mice. However, normal T cells did not convert to IL-4-producing cells when the same transwell cultures were performed with PMN from SIRS mice treated with GL. Similarly, T cells from normal mice (lower chamber) cultured with normal mouse PMN (upper chamber) did not produce IL-10 into their culture fluids, while normal T cells cultured with SIRS mouse PMN acquired an ability to produce IL-10. However, IL-10 was not produced by normal T cells cultured with PMN from GL-treated SIRS mice. Also, IFN-γ was not detected in culture fluids of transwell-cultured T cells from normal mice (lower chamber) and SIRS mouse PMN (upper chamber). PMN from SIRS mice produced CCL2, but the same cell preparations from GL-treated SIRS mice did not. These results indicate that GL has the ability to suppress SIRS-associated anti-inflammatory response manifestation in SIRS mice through the inhibition of CCL2 production by PMN.

Furthermore, we examined the production of CCL3, TNF-α, and IL-1β in cultures of PMN that were isolated from SIRS mice previously treated with GL (10 mg/kg). When PMN prepared from normal mice produce CCL3 in their culture fluids, PMN from SIRS mice treated with or without GL did not produce CCL3. Also, the production of TNF-α and IL-1β by PMN from SIRS mice was not influenced by GL treatment (data not shown). Recently, we have examined the effect of GL on the production of IL-4 by T cells stimulated with CCL2. Splenic T cells (1 × 106 cells/ml) previously stimulated with 10 ng/ml of CCL2 were cultured with or without GL (10 μg/ml) for 72 h. Culture fluids harvested were assayed for IL-4 by ELISA. In the results, T cells stimulated with CCL2 produced 600 pg/ml of IL-4 into their culture fluids. Similarly, IL-4 was produced by the same T cells after cultivation with GL. These results suggested that, although GL has an ability to inhibit the production of CCL2 by PMN, the production of IL-4 by T cells stimulated with CCL2 was not influenced by the compound.

As a typical animal model of human SIRS, mice with acute pancreatitis were utilized in this study. Typical SIRS indicators, such as multiple organ failure (amylase, GPT, and GOT) and inflammation (TNF-α, IL-1β), were found in the sera of mice with pancreatitis. These mice also had a decrease in body temperature (<36 °C) and white blood cell count (<2000/mm3). When SIRS mice were treated with GL (10 mg/kg, i.p.) 1 h after SIRS induction, these SIRS indicators were unchanged. This suggests that the inhibition of anti-inflammatory response manifestation by GL did not result from the anti-inflammatory effects of this compound.

Our results showed that GL inhibited CCL2 production in mice with SIRS. Previously, we had reported that the anti-HIV activity of GL was mediated, in part, by inhibiting CCL2 production during HIV infection [22]. However, the precise molecular mechanism of this inhibitory effect remains unclear. Several studies have indicated that the enhancer region of the CCL2 gene is inhibited by glucocorticoids [31], progesterone [32], and estrogen [33]. This enhancer region is a part of nuclear factor-κB (NF-κB). These reports suggest that the inhibition of CCL2 gene expression by these hormones might be mediated through the inhibition of NF-κB binding to the CCL2 gene. Since GL is a conjugate of a molecule of glycyrrhetinic acid (a steroid like structure) and two molecules of glucuronic acid, GL may inhibit NF-κB binding to the CCL2 gene through its influence on hormone receptors. Further studies are required to clarify the molecular mechanism for inhibiting CCL2 production by GL.

Recently, numerous papers describe the ability of macrophages (Mϕ) to display a wide variety of phenotypes depending on the cytokine environment and inflammatory process [34], [35], [36], [37]. The first population of Mϕ recruited follows activation by the engagement of Toll-like receptors [34] or the binding of IFN receptors [35]. These classically activated Mϕ display a strong potential to eradicate infections with Staphylococcus aureus, Mycobacterium avium complex, Salmonella typhimurium, Trypanosoma cruzi, lymphocytic choriomeningitis virus and influenza virus [38]. In addition, classically activated Mϕ have been characterized as the major effector cells on host resistance against CLP-induced infections [39]. This indicates that classically activated Mϕ induction is a key to controlling infections. On the other hand, it has become recognized that Mϕ can be activated by an alternative pathway involving IL-4 and IL-13 [37]. These alternatively activated Mϕ have been implicated in performing various immunosuppressive roles [38], [40]. Since IL-4 is able to suppress transcriptional activation of IFN-γ- and LPS-responsive genes in Mϕ [40], classically activated Mϕ are not generated in circumstances where alternatively activated Mϕ predominate. This may explain why patients with anti-inflammatory response that appeared in association with SIRS are susceptible to various opportunistic infections.

Recently, we have demonstrated that SIRS mice are predominated by alternatively activated Mϕ [30]. CCL2 was detected in the sera of SIRS mice, but not in normal mice. When Mϕ freshly isolated from normal mice (resident Mϕ) were cultured with SIRS mouse sera or recombinant CCL2, these Mϕ produced CCL17, a typical parameter of alternatively activated Mϕ, in their culture fluids [12]. However, CCL17 was not produced by Mϕ from mice that were injected with SIRS mouse sera and anti-CCL2 mAb in combination [12]. These results indicate that host antibacterial resistance is impaired by alternatively activated Mϕ when they are generated from resident Mϕ stimulated by CCL2, a SIRS-associated product. In this paper, we demonstrated that GL inhibits anti-inflammatory response manifestation through inhibiting CCL2 production. GL may have the potential to inhibit anti-inflammatory response-associated opportunistic infections in critically ill patients with severe SIRS.

Acknowledgments

This work was partially supported by a Grant (8690) from the Shriners of North America. The authors thank Minophagen Pharmaceutical Co., Ltd. (Tokyo, Japan) for their generous donation of GL.

References

- 1.Bone R.C., Balk R.A., Cerra F.B., Dellinger R.P., Fein A.M., Knaus W.A., Schein R.M., Sibbald W.J. Definitions for sepsis and organ failure and guidelines for the use of innovative therapies in sepsis. Chest. 1992;101:1644–1655. doi: 10.1378/chest.101.6.1644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bellingan G. Inflammatory cell activation in sepsis. Br Med Bull. 1999;55:12–29. doi: 10.1258/0007142991902277. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bone R.C. Immunological dissonance: a continuing evolution in our understanding of the systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS) and the multiple organ dysfunction syndrome (MODS) Ann Intern Med. 1996;125:680–687. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-125-8-199610150-00009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bone R.C. Systemic inflammatory response syndrome: a unifying concept of systemic inflammation. In: Fein A.M., Abraham E.M., Balk R.A., Bernard G.R., Bone R.C., Dantzker D.R., Fink M.P., editors. Sepsis and Multiorgan failure. Williams & Wilkins; 1997. pp. 3–10. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Foex B.A. Systemic responses to trauma. Br Med Bull. 1999;55:726–743. doi: 10.1258/0007142991902745. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bone R.C. Sir Isaac Newton, sepsis, SIRS, and CARS. Crit Care Med. 1996;24:1125–1128. doi: 10.1097/00003246-199607000-00010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kox W.J., Bone R.C., Krausch D., Docke W.D., Kox S.N., Wauer H., Egerer K., Querner S., Asadullah K., von Baehr R., Volk H.D. Interferon gamma-1b in the treatment of compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome. A new approach: proof of principle. Arch Intern Med. 1997;157:389–393. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Docke W.D., Randow F., Syrbe U., Krausch D., Asadullah K., Reinke P., Volk H.D., Kox W. Monocyte deactivation in septic patients: restoration by IFN-γ treatment. Nat Med. 1997;3:678–681. doi: 10.1038/nm0697-678. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Volk H.D., Reinke P., Docke W.D. Clinical aspects: from systemic inflammation to “immunoparalysis”. Chem Immunol. 2000;74:162–177. doi: 10.1159/000058753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takahashi H., Tsuda Y., Takeuchi D., Kobayashi M., Herndon D.N., Suzuki F. Influence of systemic inflammatory response syndrome on host resistance against bacterial infections. Crit Care Med. 2004;32:1879–1885. doi: 10.1097/01.ccm.0000139606.34631.61. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Norman J. The role of cytokines in the pathogenesis of acute pancreatitis. Am J Surg. 1998;175:76–83. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9610(97)00240-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tsuda Y., Takahashi H., Kobayashi M., Hanafusa T., Herndon D.N., Suzuki F. CCL2, a product of mice early after systemic inflammatory response syndrome (SIRS), induces alternatively activated macrophages capable of impairing antibacterial resistance of SIRS mice. J Leukoc Biol. 2004;76:368–373. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1203645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Suzuki H., Ohta Y., Takino T., Fujisawa K., Hirayama C. Effects of glycyrrhizin on biomedical tests in patients with chronic hepatitis-double blind trial. Asian Med J. 1983;26:423–438. [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Rossum T.G., Vulto A.G., de Man R.A., Brouwer J.T., Schalm S.W. Glycyrrhizin as a potential treatment for chronic hepatitis C. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 1998;12:199–205. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2036.1998.00309.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Numazaki K., Nagata N., Sato T., Chiba S. Effect of glycyrrhizin, cyclosporin A, and tumor necrosis factor α on infection of U-937 and MRC-5 cells by human cytomegalovirus. J Leukoc Biol. 1994;55:24–28. doi: 10.1002/jlb.55.1.24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pompei R., Flore O., Marccialis M.A., Pani A., Loddo B. Glycyrrhizic acid inhibits virus growth and inactivates virus particles. Nature. 1979;281:689–690. doi: 10.1038/281689a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Utsunomiya T., Kobayashi M., Pollard R.B., Suzuki F. Glycyrrhizin, an active component of licorice roots, reduces morbidity and mortality of mice infected with lethal doses of influenza virus. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1997;41:551–556. doi: 10.1128/aac.41.3.551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ito M., Sato A., Hirabayashi K., Tanabe F., Shigeta S., Baba M., De Clercq E., Nakashima H., Yamamoto N. Mechanism of inhibitory effect of glycyrrhizin on replication of human immunodeficiency virus (HIV) Antiviral Res. 1988;10:289–298. doi: 10.1016/0166-3542(88)90047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mori K., Sakai H., Suzuki S., Sugai K., Akutsu Y., Ishikawa M., Seino Y., Ishida N., Uchida T., Kariyone S., Endo Y., Miura A. Effect of glycyrrhizin (SNMC: Stronger Neo-Minophagen C) in hemophilia patients with HIV infection. Tohoku J Exp Med. 1989;158:25–35. doi: 10.1620/tjem.158.25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sasaki H., Takei M., Kobayashi M., Pollard R.B., Suzuki F. Effect of glycyrrhizin, an active component of licorice roots, on HIV replication in cultures of peripheral blood mononuclear cells from HIV sero(+) patients. Pathobiology. 2002;70:229–236. doi: 10.1159/000069334. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Cinatl J., Morgenstern B., Bauer G., Chandra P., Rabenau H., Doerr H.W. Glycyrrhizin, an active component of liquorice roots, and replication of SARS-associated coronavirus. Lancet. 2003;361:2045–2046. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13615-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Takei M., Kobayashi M., Li X.D., Pollard R.B., Suzuki F. Glycyrrhizin inhibits R5 HIV replication in peripheral blood monocytes treated with 1-methyladenosine. Pathobiology. 2005;72:117–123. doi: 10.1159/000084114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kobayashi H., Kobayashi M., Utsunomiya T., Herndon D.N., Pollard R.B., Suzuki F. Therapeutic protective effects of IL-12 combined with soluble IL-4 receptor against established infections of herpes simplex virus type 1 in thermally injured mice. J Immunol. 1999;162:7148–7154. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tsuda Y., Takahashi H., Kobayashi M., Hanafusa T., Herndon D.N., Suzuki F. Three different neutrophil subsets exhibited in mice with different susceptibilities to infection by methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus. Immunity. 2004;21:215–226. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2004.07.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shinada M., Azuma M., Kawai H., Sazaki K., Yoshida I., Yoshida T., Suzutani T., Sakuma T. Enhancement of interferon-γ production in glycyrrhizin-treated human peripheral lymphocytes in response to concanavalin A and to surface antigen of hepatitis B virus. Proc Soc Exp Biol Med. 1986;181:205–210. doi: 10.3181/00379727-181-42241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhang Y.H., Yoshida T., Isobe K., Rahman S.M., Nagase F., Ding L., Nakashima I. Modulation by glycyrrhizin of the cell-surface expression of H-2 class I antigens on murine tumour cell lines and normal cell populations. Immunology. 1990;70:405–410. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang Y.H., Isobe K., Nagase F., Lwin T., Kato M., Hamaguchi M., Yokochi T., Nakashima I. Glycyrrhizin as a promoter of the late signal transduction for interleukin-2 production by splenic lymphocytes. Immunology. 1993;79:528–534. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Shimizu T., Shiratori K., Sawada T., Kobayashi M., Hayashi N., Saotome H., Keith J.C. Recombinant human interleukin-11 decreases severity of acute necrotizing pancreatitis in mice. Pancreas. 2000;21:134–140. doi: 10.1097/00006676-200008000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Furukawa K., Kobayashi M., Herndon D.N., Pollard R.B., Suzuki F. Appearance of monocyte chemoattractant protein 1 (MCP-1) early after thermal injury: role in the subsequent development of burn-associated type 2 T-cell responses. Ann Surg. 2002;236:112–119. doi: 10.1097/00000658-200207000-00017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Takahashi H., Kobayashi M., Tsuda Y., Sanford A.P., Herndon D.N., Suzuki F. CCL2 as a trigger of manifestations of compensatory anti-inflammatory response syndrome in mice with severe systemic inflammatory response syndrome. J Leukoc Biol. 2005;79:789–796. doi: 10.1189/jlb.0705372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mukaida N., Zachariae C.C., Gusella G.L., Matsushima K. Dexamethasone inhibits the induction of monocyte chemotactic-activating factor production by IL-1 or tumor necrosis factor. J Immunol. 1991;146:1212–1215. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kelly R.W., Carr G.G., Riley S.C. The inhibition of synthesis of a β-chemokine, monocyte chemotactic protein-1 (MCP-1) by progesterone. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1997;239:557–561. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Frazier-Jessen M.R., Kovacs E.J. Estrogen modulation of JE/monocyte chemoattractant protein-1 mRNA expression in murine macrophages. J Immunol. 1995;154:1838–1845. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Janeway C.A., Jr., Medzhitov R. Innate immune recognition. Annu Rev Immunol. 2002;20:197–216. doi: 10.1146/annurev.immunol.20.083001.084359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.O’Shea J.J., Gadina M., Schreiber R.D. Cytokine signaling in 2002: new surprises in the Jak/Stat pathway. Cell. 2002;109:S121–S131. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(02)00701-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Seder R.A., Hill A.V. Vaccines against intracellular infections requiring cellular immunity. Nature. 2000;406:793–798. doi: 10.1038/35021239. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Goerdt S., Orfanos C.E. Other functions, other genes: alternative activation of antigen-presenting cells. Immunity. 1999;10:137–142. doi: 10.1016/s1074-7613(00)80014-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Gordon S. Alternative activation of macrophages. Nat Rev Immunol. 2003;3:23–35. doi: 10.1038/nri978. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Takahashi H., Tashiro T., Miyazaki M., Kobayashi M., Pollard R.B., Suzuki F. An essential role of macrophage inflammatory protein 1α/CCL3 on the expression of host’s innate immunities against infectious complications. J Leukoc Biol. 2002;72:1190–1197. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Hamilton T.A., Ohmori Y., Tebo J. Regulation of chemokine expression by anti-inflammatory cytokines. Immunol Res. 2002;25:229–245. doi: 10.1385/IR:25:3:229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]