The end of 2019 was marked by the emergence of a novel coronavirus, severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), which caused an outbreak of viral pneumonia (COVID-19) in Wuhan, China. At the time of writing, SARS-CoV-2, previously known as 2019-nCoV, has spread to more than 26 countries around the world. According to the WHO COVID-19 situation report-28 released on Feb 17, 2020, more than 71 000 cases have been confirmed and at least 1770 deaths.

Coronaviruses are a family of single-stranded enveloped RNA viruses that are divided into four major genera. The genome sequence of SARS-CoV-2 is 82% similar to severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus (SARS-CoV),1 and both belong to the β-genus of the coronavirus family.2 Human coronaviruses such as SARS-CoV and Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV), are known to cause respiratory and enteric symptoms.

In the SARS outbreak of 2002–03, 16–73% of patients with SARS had diarrhoea during the course of the disease, usually within the first week of illness.3 SARS-CoV RNA was only detected in stools from the fifth day of illness onwards, and the proportion of stool specimens positive for viral RNA progressively increased and peaked at day 11 of the illness, with viral RNA still present in the faeces of a small proportion of patients even after 30 days of illness.4 The mechanism for gastrointestinal tract infection of SARS-CoV is proposed to be the angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 (ACE2) cell receptor.2

In the initial MERS-CoV outbreak in 2012, a quarter of patients with MERS-CoV reported gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhoea or abdominal pain at presentation.5 Some patients initially presented with both fever and gastrointestinal symptoms before subsequent manifestation of more severe respiratory symptoms.6 Corman and colleagues7 found MERS-CoV RNA in 14·6% of stool samples from patients with MERS-CoV. In-vitro studies have shown that MERS-CoV can infect and replicate in human primary intestinal epithelial cells, potentially via the dipeptidyl peptidase 4 receptor.8 In-vivo studies showed inflammation and epithelial degeneration in the small intestines, with subsequent development of pneumonia and brain infection.8 These results suggest that MERS-CoV pulmonary infection was secondary to the intestinal infection.

In early reports from Wuhan, 2–10% of patients with COVID-19 had gastrointestinal symptoms such as diarrhoea, abdominal pain, and vomiting.9, 10 Abdominal pain was reported more frequently in patients admitted to the intensive care unit than in individuals who did not require intensive care unit care, and 10% of patients presented with diarrhoea and nausea 1–2 days before the development of fever and respiratory symptoms.9 SARS-CoV-2 RNA has been detected in the stool of a patient in the USA.11 The binding affinity of ACE2 receptors is one of the most important determinants of infectivity, and structural analyses predict that SARS-CoV-2 not only uses ACE2 as its host receptor, but uses human ACE2 more efficiently than the 2003 strain of SARS-CoV (although less efficiently than the 2002 strain).2

Data exist to support the notion that SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV are viable in environmental conditions that could facilitate faecal–oral transmission. SARS-CoV RNA was found in the sewage water of two hospitals in Beijing treating patients with SARS.12 When SARS-CoV was seeded into sewage water obtained from the hospitals in a separate experiment, the virus was found to remain infectious for 14 days at 4°C, but for only 2 days at 20°C.12

SARS-CoV can survive for up to 2 weeks after drying, remaining viable for up to 5 days at temperatures of 22–25°C and 40–50% relative humidity, with a gradual decline in virus infectivity thereafter.13 Viability of the SARS-CoV virus decreased after 24 h at 38°C and 80–90% relative humidity.13 MERS-CoV is viable in low temperature, low humidity conditions. The virus was viable on different surfaces for 48 h at 20°C and 40% relative humidity, although viability decreased to 8 h at 30°C and 80% relative humidity conditions.14 At present, no viability data are available for SARS-CoV-2.

The viability of SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV under various conditions and their prolonged presence in the environment suggest the potential for coronaviruses to be transmitted via contact or fomites. SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV are both viable in conditions with low temperatures and humidity.12, 13, 14 Although direct droplet transmission is an important route of transmission, faecal excretion, environmental contamination, and fomites might contribute to viral transmission. Considering the evidence of faecal excretion for both SARS-CoV and MERS-CoV, and their ability to remain viable in conditions that could facilitate faecal–oral transmission, it is possible that SARS-CoV-2 could also be transmitted via this route.

The possibility of faecal–oral transmission of SARS-CoV-2 has implications, especially in areas with poor sanitation. Coronaviruses are susceptible to antiseptics containing ethanol, and disinfectants containing chlorine or bleach.15 Strict precautions must be observed when handling the stools of patients infected with coronavirus, and sewage from hospitals should also be properly disinfected. The importance of frequent and proper hand hygiene should be emphasised.

Future research on the possibility of faecal–oral transmission of SARS-CoV-2 should include environmental studies to determine whether the virus remains viable in conditions that would favour such transmission. Study of the enteric involvement and viral excretion of SARS-CoV-2 in faeces is required to investigate whether faecal concentrations of SARS-CoV-2 RNA correlate with the severity of the disease and presence or absence of gastrointestinal symptoms, and whether faecal SARS-CoV-2 RNA can also be detected in the incubation or convalescence phases of COVID-19.

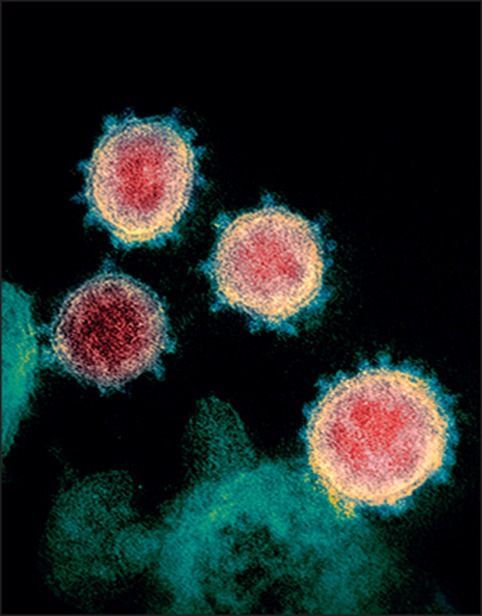

© 2020 NIAID-RML/National Institutes of Health/Science Photo Library

Acknowledgments

We declare no competing interests.

References

- 1.Chan JF, Kok KH, Zhu Z, et al. Genomic characterization of the 2019 novel human-pathogenic coronavirus isolated from a patient with atypical pneumonia after visiting Wuhan. Emerg Microbes Infect. 2020;9:221–236. doi: 10.1080/22221751.2020.1719902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wan Y, Shang J, Graham R, Baric RS, Li F. Receptor recognition by novel coronavirus from Wuhan: an analysis based on decade-long structural studies of SARS. J Virol. 2020 doi: 10.1128/JVI.00127-20. published online Jan 29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.WHO issues consensus document on the epidemiology of SARS. Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2003;78:373–375. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chan KH, Poon LL, Cheng VC, et al. Detection of SARS coronavirus in patients with suspected SARS. Emerg Infect Dis. 2004;10:294–299. doi: 10.3201/eid1002.030610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Assiri A, Al-Tawfiq JA, Al-Rabeeah AA, et al. Epidemiological, demographic, and clinical characteristics of 47 cases of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus disease from Saudi Arabia: a descriptive study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2013;13:752–761. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(13)70204-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Mackay IM, Arden KE. MERS coronavirus: diagnostics, epidemiology and transmission. Virol J. 2015;12:222. doi: 10.1186/s12985-015-0439-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Corman VM, Albarrak AM, Omrani AS, et al. Viral shedding and antibody response in 37 patients with Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2016;62:477–483. doi: 10.1093/cid/civ951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zhou J, Li C, Zhao G, et al. Human intestinal tract serves as an alternative infection route for Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus. Sci Adv. 2017;3 doi: 10.1126/sciadv.aao4966. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wang D, Hu B, Hu C, et al. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. JAMA. 2020 doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. published online Feb 7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen N, Zhou M, Dong X, et al. Epidemiological and clinical characteristics of 99 cases of 2019 novel coronavirus pneumonia in Wuhan, China: a descriptive study. Lancet. 2020;395:507–513. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30211-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Holshue ML, DeBolt C, Lindquist S, et al. First case of 2019 novel coronavirus in the United States. N Engl J Med. 2020 doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2001191. published online Jan 31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang XW, Li J, Guo T, et al. Concentration and detection of SARS coronavirus in sewage from Xiao Tang Shan Hospital and the 309th Hospital of the Chinese People's Liberation Army. Water Sci Technol. 2005;52:213–221. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan KH, Peiris JS, Lam SY, Poon LL, Yuen KY, Seto WH. The effects of temperature and relative humidity on the viability of the SARS coronavirus. Adv Virol. 2011;2011 doi: 10.1155/2011/734690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van Doremalen N, Bushmaker T, Munster VJ. Stability of Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) under different environmental conditions. Euro Surveill. 2013;18 doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.es2013.18.38.20590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Geller C, Varbanov M, Duval RE. Human coronaviruses: insights into environmental resistance and its influence on the development of new antiseptic strategies. Viruses. 2012;4:3044–3068. doi: 10.3390/v4113044. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]