Abstract

The outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19) caused a worldwide pandemic. Less than 6 weeks after the first confirmed cases in Korea, the patient number exceeded 5,000, which overcrowded limited hospital resources and forced confirmed patients to stay at home. To allocate medical resources efficiently, Korea implemented a novel institution for the purpose of treating patients with cohort isolation out of hospital, namely the Community Treatment Center (CTC). Herein, we report results of the initial management of patients at one of the largest CTC in Korea. A total of 309 patients were admitted to our CTC. During the first two weeks, 7 patients were transferred to the hospital because of symptom aggravation and 107 patients were discharged without any complication. Although it is a novel concept and may have some limitations, CTC may be a very cost-effective and resource-saving strategy in managing massive cases of COVID-19 or other emerging infectious diseases.

Keywords: Community Treatment Center, Medical Resources, SARS-CoV-2, COVID-19

Graphical Abstract

The outbreak of Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), which originated in Wuhan, China and is caused by severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 2 (SARS-CoV-2), progressed worldwide with more than 200,000 confirmed cases.1 World Health Organization characterized COVID-19 as a pandemic on March 11, and it is currently spreading exponentially among many countries.1 To prevent the transmission of emerging infectious disease, it is optimal to treat all confirmed patients in a negative pressure isolation room inside a hospital, as was the case of the Middle East respiratory syndrome outbreak in South Korea in 2015.2 However, medical resources, such as hospital beds, are not available indefinitely and often act as an impediment to managing a pandemic of an emerging infectious disease. Especially patients with severe symptoms, who need oxygen treatment or an invasive ventilator, must be admitted and treated in the hospital. However, if patients with mild symptoms are already occupying the hospital for the purpose of preventing disease transmission, patients with severe symptoms may not receive proper treatment.

In Korea, the first confirmed cases were identified on January 20. For the first 4 weeks after the initial outbreak, the disease spread slowly with less than 100 confirmed cases, with all the confirmed patients being admitted to negative pressure isolation rooms in hospitals.3 However, the number of patients rapidly surged after that, exceeding 5,000 within 6 weeks, most of them in the Daegu and Gyeongbuk regions. This surge overcrowded regional hospital resources and forced some confirmed patients to stay at home.3,4 There was even a report of an out-of-hospital death on February 27 of a patient with confirmed COVID-19 infection awaiting admission due to shortage of hospital resources.

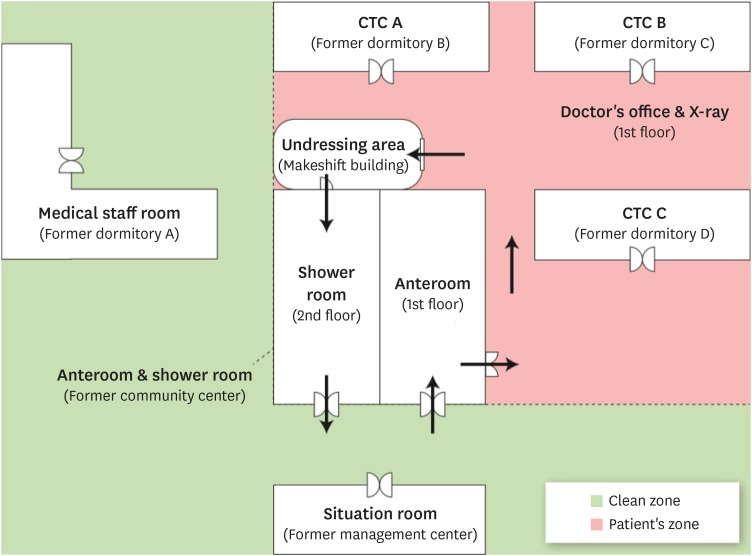

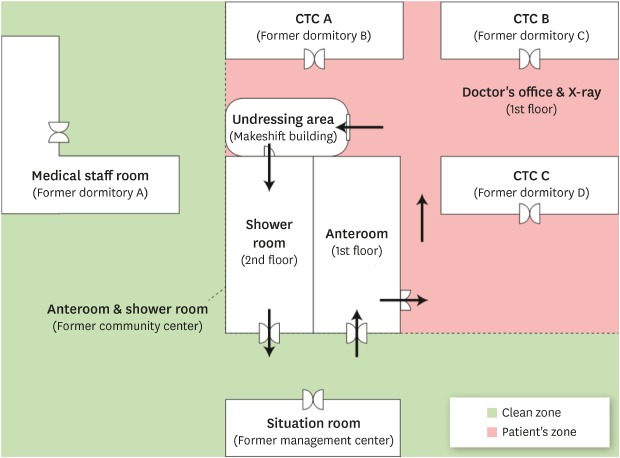

To allocate medical resources efficiently, a novel institution with the purpose of treating patients with cohort isolation out of the hospital, namely the Community Treatment Center (CTC), was designed and implemented in Korea. The CTC is an independent building outside a hospital based on the concept that patients with mild symptoms do not require advanced medical resources, although they require isolation to prevent transmission and active surveillance in case they develop more severe symptoms. Utilizing CTCs has several advantages compared to isolating patients at home: strict isolation with active surveillance of patients is possible; it also lowers the risk associated with collecting viral specimens and the possibility of cross-infections. As of March 18, a total of 12 CTCs are operating in Korea, and more CTCs in other regions are preparing to open shortly. Herein, we report the initial management and treatment results of patients at Gyeongbuk-Daegu 7 CTC, one of the largest CTCs in Korea. The building currently being utilized as Gyeongbuk-Daegu 7 CTC, located in Gumi, Gyeongbuk, was previously a dormitory building owned by a private company and is now renovated as a CTC. Healthcare providers currently working at the center consist of 7 physicians, 5 nurses and 1 radiologic technician from Kangwon National University Hospital; 7 public health doctors from the Ministry of Health and Welfare; and volunteer healthcare providers (12 nurses and 12 nursing assistants). Physicians worked on a two-shift system, taking charge of active surveillance of patients and collecting viral specimens from patients. Nurses worked on a three-shift system and assisted physicians with such tasks. The clean zone, where healthcare providers work, is separated from the patients' zone, where patients reside, to prevent cross-infection between healthcare providers and patients (Fig. 1). Healthcare providers are required to wear personal protective equipment (PPE) of inner and outer gloves, N95 respirator, goggles, and hooded coveralls when entering the patients' zone.5 Patients were also instructed to stay in their rooms to prevent cross-infection between patients. In the patients' zone, two negative pressure rooms for a mobile radiograph imaging facility and a doctor's office was installed to examine patients with symptoms of coronavirus. Candidates for CTC admission were confirmed COVID-19 patients with real-time reverse transcriptase polymerase chain reaction (rRT-PCR) method and considered by authorities as patients without severe symptoms using guidelines from the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (KCDC).6,7 Exclusion criteria were as follows: patients with underlying chronic severe medical conditions such as heart failure or chronic kidney disease and patients with high fever or dyspnea – all of whom likely required advanced medical treatment. Patients admitted were initially checked for their symptoms and underlying diseases; patients 55 years of age or older received routine chest radiographs to rule out asymptomatic pneumonia. After their admission, their body temperature was monitored twice a day. To minimize access of healthcare providers to the patients' zone and to communicate more effectively, we encouraged patients to install a specialized mobile application (inPHR®, SoftNet, Seoul, Korea) to report their body temperature, of which adherence reached more than 80% (Fig. 2). Patients who were inexperienced in using a mobile application were instead encouraged to use telephone communication. Although the center is strictly not a medical institution, we used a digital health information system, as well as a picture archiving and communication system provided by Kangwon National University Hospital and acted as if patients were admitted to a special hospital ward to communicate orders and laboratory/radiological test results. Medications for symptomatic treatment such as antipyretics were prescribed using this method, although antiviral agents were not prescribed. If patients developed worsening respiratory symptoms or fever, chest radiograph and pulse oximetry were performed. Patients were transferred to the hospital equipped for specialized treatment if a pneumonia-like lesion on chest radiography or desaturation was detected. Patients routinely received viral testing weekly. Upper respiratory tract specimens were obtained from the nasopharyngeal and oropharyngeal swab, as was recommended by the KCDC, and rRT-PCR was employed to detect the virus using the published sequences.7,8 If the test came out negative for a patient, the following test was conducted 24 hours later. If the second test also produced a negative result, the patient was then discharged, as was recommended by the KCDC.7 All healthcare providers monitored themselves for their body temperatures and respiratory symptoms twice a day.

Fig. 1. Illustration of Gyeongbuk-Daegu 7 CTC. Arrows indicate the movement direction of healthcare providers.

CTC = community treatment center.

Fig. 2. Monitoring body temperature and symptoms of patients using specialized mobile application (inPHR®, SoftNet, Seoul, Korea).

Three hundred and nine patients were admitted on March 9, all of whom were confirmed with COVID-19 but were isolated in their home due to the shortage of hospital beds. 124 (40.1%) of them were male. Their median age was 31 (range: 7–77) and 12 patients (3.9%) were 18 years old or younger. 125 (40.4%) patients used solitary rooms and 184 (59.6%) used shared space with a separate room, of whom 32 (10.4%) were relatives. The patients were admitted to the CTC after a median of 7 (range: 3–14) days since the diagnosis of COVID-19. Patients presented with various symptoms such as cough (50 patients, 16.2%), rhinorrhea (49 patients, 15.9%), sputum (39 patients, 12.7%), sore throat (24 patients 7.8%), and chest discomfort (12 patients, 3.9%). 176 (57.1%) patients were asymptomatic at the time of admission. Psychiatric symptoms including depression, anxiety, and insomnia increased as the treatment progressed and we introduced remote counseling services using the mobile application in cooperation with psychiatrists at Kangwon National University Hospital. Other unusual symptoms include epistaxis and musculoskeletal pain. There were no reports of symptoms requiring emergent medical care such as altered mental status, syncope, or severe dyspnea. 7 (2.3%) of the patients were transferred to the hospital after a median 3.5 (range: 0–7) days of admission. Two patients due to pneumonia, 1 due to suspicious chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, 1 due to unremitted high fever, 1 patient due to severe psychiatric compliant including suicidal ideation, and 2 patients transferred to the hospital on their own will. Of them, two patients were transferred to the hospital shortly after admission, due to chest radiograph abnormalities at the initial screening.

All patients received viral tests 3 or 4 days after their admission. Among them, 101 (32.7%) patients received negative results. 69 (22.3%) patients received consecutive negative results and were discharged a median of 13 (range: 8–23) days after their initial diagnosis. Secondary viral testing was obtained 8 days after admission and 85 (27.5%) patients received negative results. 38 (12.3%) of them received consecutive negative results and were discharged a median of 18 (range: 15–23) days after their initial diagnosis. As of the end of the second week since the first admission of patients, there were no reported cases of cross-infection of healthcare providers.

There were many limitations regarding the installation and the operation of CTC. Firstly, this facility does not have a negative-pressure air conditioning system and we divided the clean zone and the patient’s zone arbitrarily, anticipating natural ventilation effects. Secondly, the standard recommended protocol of changing PPEs between every testing of patients, to prevent cross-infection among patients and specimen contamination, were not strictly adhered to due to the lack of resources.5 In fact, a considerable number of patients received negative results initially but then got positive results on the consecutive test. These results may be due to window periods of virus infection, but the possibility of cross-infection among patients during sample collection or contamination of specimens cannot be excluded. Also, due to the limitations of the original facility, not all patients could receive solitary rooms, although they used separate bedrooms and bathroom inside the shared space and were promptly reassigned to solitary rooms as soon as other patients were discharged and solitary rooms became available. If more CTCs are to be operated, as is expected, this problem will be ameliorated. Also, as we selected and admitted patients under the criteria limited to their age and a simple questionnaire, the risk factors and the severity of the disease of each patient were not fully understood, although we could identify and transfer some high-risk patients using the initial chest radiograph. As more about the nature and risk factors of COVID-19 are being identified, it would become easier for us to identify the risk and severity of the patients admitted to CTC.

Nevertheless, in terms of the efficient allocation of medical resources in a pandemic status such as this case, CTC is thought to be a novel, cost-effective and resource-saving strategy. In many countries, hospital beds are outnumbered by COVID-19 patients with mild symptoms, which in turn hinders more severe patients from being hospitalized that may lead to fatalities of patients awaiting hospitalization.1 This system, in which healthcare providers examine patients and immediately transfer patients in need of advanced care to hospitals while successfully preventing the transmission of infection, will be applicable to other countries or any other emerging infectious diseases in addition to COVID-19. CTCs can be a very cost-effective alternative since facilities and centers that are already in place in the regional community can be utilized.

After Korea implemented CTCs on March 2, the number of patients infected with COVID-19 who had no other choice but to be isolated at home due to the shortage of hospital beds have dropped from 3,000 to less than 300 on March 18, as CTCs could accommodate most of them.3 All 12 CTCs, which are currently operating, are performing the role of controlling the source of infection and screening for patients with severe conditions. However, the criteria and the method of the screening, admission, and discharge of patients varies widely between centers and our management method does not represent overall CTCs. As more data and experiences are accumulated, CTCs are expected to provide more standardized evaluation and treatment. Data from other CTCs, including the transportation system of patients with aggravating symptoms, need to be comprehensively analyzed to further describe advantages and challenges of CTCs in managing the COVID-19 pandemic.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We appreciate Won Sub Oh MD, PhD who established the system of infection control for this CTC. We would like to thank all of the staff at Gyeongbuk-Daegu 7 CTC for their dedicated efforts and Kangwon National University Hospital for its unsparing support of human and material resources. We also deeply appreciate LG Display Co., Ltd. for their support of facilities and commodities for healthcare providers. Lastly, we would like to thank the Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention and the Ministry of Health and Welfare for their administrative support, including the transportation system of patients with aggravating symptoms.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

- Conceptualization: Kim CH, Kim CH.

- Data curation: Park PG, Kim CH, Heo Y.

- Formal analysis: Park PG, Kim CH.

- Investigation: Heo Y, Kim TS, Park CW.

- Methodology: Kim TS, Park CW.

- Supervision: Kim CH.

- Visualization: Heo Y.

- Writing - original draft: Park PG, Kim CH.

- Writing - review & editing: Kim TS, Park CW, Kim CH.

References

- 1.World Health Organization. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) Situation Report??3. [Updated 2020]. [Accessed March 18, 2020]. https://www.who.int/docs/default-source/coronaviruse/situation-reports/20200313-sitrep-53-covid-19.pdf.

- 2.Kim KH, Tandi TE, Choi JW, Moon JM, Kim MS. Middle East respiratory syndrome coronavirus (MERS-CoV) outbreak in South Korea, 2015: epidemiology, characteristics and public health implications. J Hosp Infect. 2017;95(2):207–213. doi: 10.1016/j.jhin.2016.10.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. The updates of COVID-19 in the Republic of Korea. [Updated 2020]. [Accessed March 18, 2020]. https://www.cdc.go.kr/board/board.es?mid=a20501000000&bid=0015.

- 4.Korean Society of Infectious Diseases Korean Society of Pediatric Infectious Diseases; Korean Society of Epidemiology; Korean Society for Antimicrobial Therapy; Korean Society for Healthcare-associated Infection Control and Prevention; Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Report on the epidemiological features of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) outbreak in the Republic of Korea from January 19 to March 2, 2020. J Korean Med Sci. 2020;35(10):e112. doi: 10.3346/jkms.2020.35.e112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.World Health Organization. Rational use of personal protective equipment for coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19). Interim guidance 27 February 2020. [Updated 2020]. [Accessed March 18, 2020]. https://www.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/331215/WHO-2019-nCov-IPCPPE_use-2020.1-eng.pdf.

- 6.World Health Organization. Laboratory testing for 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) in suspected human cases. [Updated 2020]. [Accessed March 18, 2020]. https://www.who.int/publications-detail/laboratory-testing-for-2019-novel-coronavirus-in-suspected-human-cases-20200117.

- 7.Korea Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Guideline for management of COVID-19. [Updated 2020]. [Accessed March 23, 2020]. http://www.cdc.go.kr/board.es?mid=a20507020000&bid=0019&act=view&list_no=366558.

- 8.Corman VM, Landt O, Kaiser M, Molenkamp R, Meijer A, Chu DK, et al. Detection of 2019 novel coronavirus (2019-nCoV) by real-time RT-PCR. Euro Surveill. 2020;25(3):2000045. doi: 10.2807/1560-7917.ES.2020.25.3.2000045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]