Abstract

Background

Gallstone disease affects up to 20% of the European population, and cholelithiasis is the most common reason for hospitalization in gastroenterology.

Methods

This review is based on pertinent publications retrieved by a selective search of the literature, including the German clinical practice guidelines on the diagnosis and treatment of gallstones and corresponding guidelines from abroad.

Results

Regular physical activity and an appropriate diet are the most important measures for the prevention of gallstone disease. Transcutaneous ultrasonography is the paramount method of diagnosing gallstones. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiography should only be carried out as part of a planned therapeutic intervention; endosonography beforehand lessens the number of endoscopic retrograde cholangiographies that need to be performed. Cholecystectomy is indicated for patients with symptomatic gallstones or sludge. This should be performed laparoscopically with a four-trocar technique, if possible. Routine perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis is not necessary. Cholecystectomy can be performed in any trimester of pregnancy, if urgently indicated. Acute cholecystitis is an indication for early laparoscopic cholecystectomy within 24 hours of admission to hospital. After successful endoscopic clearance of the biliary pathway, patients who also have cholelithiasis should undergo laparoscopic cholecystectomy within 72 hours.

Conclusion

The timing of treatment for gallstone disease is an essential determinant of therapeutic success.

According to the European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL), around 20% of Europeans are affected by gallstone disease (1). Cholelithiasis leads to more hospital admissions than any other gastroenterological condition. However, only half of the people with documented gallstones ever experience symptoms requiring treatment. In Germany, more than 175 000 cholecystectomies are carried out each year because of cholelithiasis (2).

Learning goals

This article is intended to provide the reader with:

Familiarity with the interdisciplinary treatment of gallstones

Knowledge of the specific treatment for cholelithiasis and its potential complications

An understanding of the clinical significance of the timing of treatment.

Methods

We summarize the updated German clinical practice guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of gallstones (serial no. 021/008 in the registry of the Association of the Scientific Medical Societies in Germany, AWMF) and compare them with the current guidelines from other countries (1– 10).

Prevention

Advanced age, female sex, and a hypercaloric diet rich in carbohydrates and poor in fiber, together with obesity and genetic factors, are the most important predisposing factors for gallstones. Only a small number of valid, sufficiently robust studies have been published, but it seems that regular exercise, an appropriate diet, and maintenance of normal body weight seem to be decisive preventive measures.

Incidence.

In Germany, more than 175 000 cholecystectomies are carried out each year because of cholelithiasis.

Prevention.

General pharmacological prevention of gallstones is not recommended, even in the presence of predisposing factors.

General pharmacological prevention of gallstones by means of ursodeoxycholic acid, which stops the formation of cholesterol crystals in the bile, is not recommended. If, however, there is a high risk of formation of gallbladder sludge or gallstones, e.g., as a consequence of weight loss by dieting or after bariatric surgery, it may make sense to give prophylactic ursodeoxycholic acid (500 g/d) for a limited time. In this regard, a randomized controlled trial published in 2003 demonstrated a significantly reduced risk of gallstones 24 months after restrictive gastric bypass surgery (8% vs. 30%) (11).

Although up to 20% of patients with an initially inconspicuous gallbladder develop biliary symptoms within 3 years after laparoscopic Roux-en-Y gastric bypass (RYGB), simultaneous prophylactic cholecystectomy is not advised. This is in accordance with the recommendation of the EASL (1).

Hormone replacement therapy (HRT) in menopausal women also bears an elevated risk of biliary diseases, especially cholecystitis. This was shown as early as 1994 in a group of postmenopausal women who had received HRT (12).

If intrahepatic stones or common bile duct stones occur in a patient who is still young, molecular genetic analysis of the phospholipid transporter ABCB4 in the liver can be requested. Mutations of this transporter lead to chronic cholangiopathy and favor the formation of cholesterol gallstones. This low phospholipid-associated cholelithiasis (LPAC) can be prevented by the administration of ursodeoxycholic acid (2).

Diagnosis

Colicky pain in the upper abdomen/epigastrium, jaundice, and fever are among the cardinal symptoms of gallbladder and bile duct disease. If the patient clearly recalls episodes of pain lasting more than 15 min in the epigastrium or right upper abdomen, one can assume the presence of biliary colic. The pain may radiate into the right shoulder or the back and is often accompanied by nausea, sometimes with vomiting. However, there is no consensus regarding the specificity of the biliary symptoms. Symptomatic gallstone disease can be responsible for a wide variety of symptoms. In more than half of the patients affected, the initial manifestation is followed by further attacks of pain. The annual complication rate is 1–3% for symptomatic gallstones, but only 0.1–0.3% in patients with asymptomatic stones (13). The presence of multiple stones in the gallbladder increases the risk of symptomatic choledocholithiasis or acute cholecystitis.

Prevention.

Regular exercise, an appropriate diet, and maintenance of normal body weight seem to be decisive in the prevention of gallstones.

The presence or absence of cholelithiasis should be demonstrated by systematically conducted transcutaneous sonography. With a sensitivity of >95% and specificity of practically 100%, sonography is the method of choice for gallbladder stones (14, 15). The aim of the examination is complete depiction of the gallbladder in various planes and with the patient in various positions, in order to capture the gravity-dependent changes of all stones, large or small. In the UK, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) recommends that patients suspected to have gallstones should undergo abdominal ultrasonography and blood tests including determination of liver function parameters (3).

Acute cholecystitis is the most frequently occurring complication of gallstone disease (over 63 500 hospital admissions per year in Germany), and is caused in 90% of cases by a concrement that—permanently or temporarily—occludes the cystic duct (2, 16). This mechanical obstruction is accompanied by chemical inflammation caused by the release of lysolecithin and, in some patients, by subsequent bacterial inflammation. Often, all three factors are present in combination.

Diagnosis of cholelithiasis.

The presence or absence of cholelithiasis should be demonstrated by systematically conducted transcutaneous sonography.

The diagnosis of acute cholecystitis is based on the presence of three of the following four symptoms: right-sided upper abdominal pain, positive Murphy sign (circumscribed pain over the gallbladder on direct pressure), leukocytosis, and fever. In addition, cholelithiasis or the sonographic signs of cholecystitis should be present. Together with the sonographic/palpatory Murphy sign, these include thickening and layering of the gall bladder wall (three-layer pattern). Further sonographic signs of acute cholecystitis may include gallbladder hydrops, fluid around the gallbladder, and increased wall perfusion. If the ultrasound findings are unclear, or if complications are suspected, computed tomography (CT) and magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) may provide useful information (17– 20). Transcutaneous sonography allows simultaneous assessment of the intrahepatic and extrahepatic bile ducts (21– 23) (figure 1). Using these criteria, acute cholecystitis can be diagnosed clearly and reproducibly (8) (box 1).

Figure 1.

Sonographic appearance of acute cholecystitis in cholelithiasis

BOX 1. Acute cholecystitis.

-

Diagnosis based on presence of three of four symptoms:

right-sided upper abdominal pain

Murphy sign

leukocytosis

fever

plus

cholelithiasis (concrements/sludge)

or

sonographic signs of cholecystitis (thickening/layering of the gall bladder wall [three-layer pattern])

Whenever clinical examination or the patient’s history arouse suspicion of choledocholithiasis, total bilirubin, gamma-glutamyltransferase (γ-GT), alkaline phosphatase (AP), alanine aminotransferase/aspartate aminotransferase (ALT/AST), and lipase should be determined and systematically conducted transabdominal sonography performed.

A range of criteria—clinical variables, laboratory parameters, and sonographic findings—can be used to categorize as high, moderate, or low the probability that a patient with cholelithiasis also has choledocholithiasis (box 2).

BOX 2. Criteria for simultaneous choledocholithiasis in a patient with cholelithiasis.

-

High likelihood of simultaneous choledocholithiasis (> 50%)

Sonographically widened extrahepatic bile duct (>7 mm) + hyperbilirubinemia + elevation of γ-GT, AP, ALT, or AST or

Sonographic demonstration of bile duct concrements or

Clinical and laboratory criteria of ascending cholangitis

-

Moderate likelihood of simultaneous choledocholithiasis (5–50%)

Criteria for neither high nor low likelihood fulfilled

-

Low likelihood of simultaneous choledocholithiasis (< 5%)

Normal bile duct width (up to 7 mm)

Total bilirubin, γ-GT, AP, ALT, or AST not elevated during current pain episode

Absence of episodes with biliary pancreatitis, acholic stools, and/or urobilinogenuria or bilirubinuria in recent past

ALT, alanine aminotransferase; AP, alkaline phosphatase; AST, aspartate aminotransferase; y-GT, gamma-glutamyltransferases

This assessment of the risk of choledocholithiasis depending on various predictive factors is based on guidelines published by the American Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy (ASGE) in 2010 (24).

Clinical practice.

A range of criteria—clinical variables, laboratory parameters, and sonographic findings—can be used to categorize as high, moderate, or low the probability that a patient with cholelithiasis also has choledocholithiasis.

Only in patients with a high probability of the presence of choledocholithiasis should one carry out endoscopic retrograde cholangiography (ERC) with therapeutic intent. If the likelihood is moderate or low, endosonography or magnetic resonance cholangiography (MRC) is recommended to determine whether ERC is indicated.

In the case of direct sonographic demonstration of choledocholithiasis and/or in acute cholangitis, ERC is primarily indicated, because as well as identifying the bile duct stones it allows simultaneous therapeutic intervention, i.e., biliary sphincterotomy and stone extraction. If choledocholithiasis is strongly suspected but has not been confirmed by imaging, primary ERC is justified because its sensitivity and specificity are both over 90%.

Endosonography.

Endosonography has the highest sensitivity for the detection of stones in the common bile duct.

However, it may also be expedient, in this situation, first to employ other imaging procedures such as endosonography or MRC, as this reduces by more than half the number of high-risk patients subjected to ERC. Choledocholithiasis can be ruled out in the absence of clinical, biochemical, and sonographic predictors. Usually, therefore, no further imaging procedures or ERC are necessary before cholecystectomy.

Endosonography has the highest sensitivity for the detection of stones in the common bile duct. In the hands of an experienced examiner, endosonography has a sensitivity of practically 100% and a specificity of over 93% for demonstration/exclusion of stones in the duct (2, 25).

MRC also possesses high sensitivity and specificity for choledocholithiasis, but its detection of small concrements (<5 mm) is limited in comparison with endosonography (26). Although direct comparison of the two methods shows similar specificity, the sensitivity of endosonography is significantly superior (97% vs. 87%) (25).

The NICE recommendations confirm that endoscopic ultrasound and MRI are highly efficient in the detection of choledocholithiasis. Nevertheless, unless availability or relative expertise plays a part, neither modality is clearly preferred over the other (3).

If there is clinical suspicion of acute cholangitis, documentation of the clinical symptoms should be accompanied by determination of laboratory parameters of inflammation. This includes infection parameters such as leukocytes and C-reactive protein (CRP) and cholestasis parameters such as bilirubin, alkaline phosphatase, γ-GT, and transaminases.

Furthermore, transabdominal sonography of the bile ducts should be carried out to detect or rule out widening of a duct (>7 mm), a concrement, or any other impediment to drainage. If, despite clinical suspicion of acute cholangitis, sonography fails to show widening, a concrement, or any other kind of blockage, endosonography or MRC should be performed.

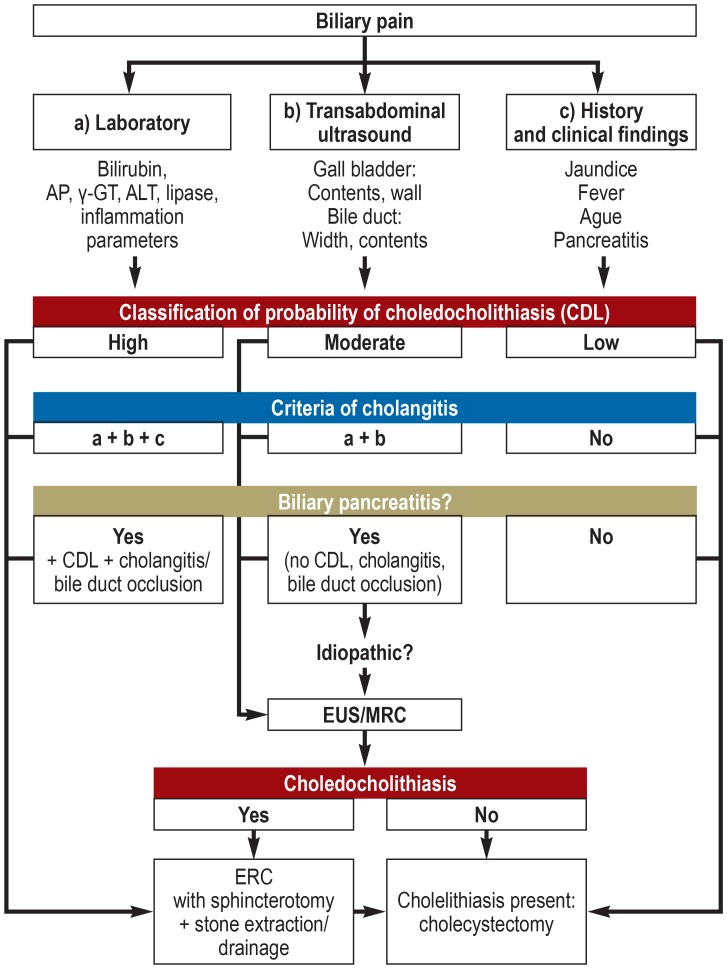

The primary measure in patients with acute pancreatitis and concurrent choledocholithiasis, bile duct occlusion, or cholangitis should be ERC with therapeutic intent. If the cause is not identified, the next step is endosonography or, alternatively, MRC. For biliary indications endosonography and ERC can be performed in immediate succession, provided endoscopic treatment is indicated (figure 2).

Figure 2.

Algorithm for the diagnosis and treatment of gallstones. AP, alkaline phosphatase; ALT, alanine aminotransferase; CDL, choledocholithiasis; ERC, endoscopic retrograde cholangiography; EUS, endosonography; GT, glutamyltransferase; MRC, magnetic resonance cholangiography

Treatment

As a rule, treatment for cholelithiasis is indicated only in the presence of symptoms. There is usually no indication for cholecystectomy in asymptomatic patients unless they are found to have gallstones >3 cm, polyps >1 cm, or porcelain gallbladder, all of which are associated with an elevated risk of gallbladder cancer (2).

Asymptomatic cholelithiasis.

Asymptomatic cholelithiasis is usually not an indication for cholecystectomy.

The clinical practice guidelines issued by NICE and the EASL also recommend conservative treatment of asymptomatic cholelithiasis (1, 3).

Treatment with ursodeoxycholic acid should be reserved for the occasional symptomatic patients with small stones presumably formed from cholesterol or proven gallbladder sludge. In every case the patient should be informed beforehand about the option of curative cholecystectomy. Extracorporeal shock-wave lithotripsy (ESWL) is not recommended for cholelithiasis.

Uncomplicated cholelithiasis.

Cholecystectomy is the treatment of choice for both uncomplicated symptomatic cholelithiasis and gallbladder sludge with the characteristic biliary pain.

The appropriate treatment for biliary colic is medication with nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs. Spasmolytics or nitroglycerin can be added, and if the pain is extremely severe, opioids may be used (28).

Suspicion of acute cholangitis.

Documentation of the clinical symptoms should be accompanied by determination of laboratory parameters of inflammation. This includes infection parameters such as leukocytes and CRP and cholestasis parameters such as bilirubin, AP, γ-GT, and transaminases.

If the clinical findings point to acute biliary colic, one must differentiate between immediate analgesic therapy on the one hand and causal therapy on the other. In acute cholecystitis with signs of sepsis, cholangitis, abscess, or perforation, antibiotics must be administered without delay. On the other hand, there is no evidence supporting the use of antibiotics in the treatment of uncomplicated cholecystitis.

Cholecystectomy.

Laparoscopic surgery is usually the standard method for cholecystectomy.

Cholecystectomy is the treatment of choice for both uncomplicated symptomatic cholelithiasis and proven gallbladder sludge with the characteristic biliary pain (29). Routine esophagogastroduodenoscopy is not indicated before elective cholecystectomy (2, 4, 30). The treatment goals of cholecystectomy are prevention or reduction of renewed biliary pain; avoidance of later and elimination of existing complications of cholelithiasis; and prevention of gallbladder cancer in high-risk patients.

Separate treatment of simultaneously detected cholelithiasis and choledocholithiasis is indicated. The first step is endoscopic removal of the bile duct stones, followed—ideally within 72 h—by cholecystectomy. Early cholecystectomy reduces the occurrence of biliary events by around 90%. A stone-free functioning gallbladder can be left in place.

In contrast, the Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons (SAGES) states that ERC with stone extraction can be optionally performed before, during, or after cholecystectomy, with only small differences in morbidity and mortality and rates of successful stone extraction comparable with laparoscopic bile duct exploration (5) (table 1).

Table 1. The treatments recommended in different guidelines and studies.

| German clinical practice guideline (2) | EASL (1) | SAGES (5) | Tokyo (7, 10, 22) |

| Optimal timing of treatment after diagnosis of acute cholecystitis | |||

| Acute cholecystitis is an indication for early laparoscopic cholecystectomy (recommendation grade A, evidence level I, strong consensus). This should be carried out within 24 h after hospital admission (recommendation grade B, evidence level I, strong consensus). | Early cholecystectomy (preferably within 72 h after admission) should be carried out by an experienced surgeon (high evidence, strong recommendation). | Early cholecystectomy (within 24–72 h of diagnosis) can be carried out without increased rates of conversion to open surgery or elevated complication rates, and can lower hospital costs and total length of stay (evidence level I, recommendation grade A). | Treatment strategy considered after assessment of acute cholecystitis severity. For both grade I (mild) and grade II (moderate), laparoscopic cholecystectomy should ideally be carried out soon after onset of symptoms, provided the patient can tolerate surgery. Grade III (severe) acute cholecystitis: The degree of organ dysfunction should be determined and attempts made to normalize function (evidence level D; recommendation grade II). |

| Treatment strategy in patients with simultaneous choledocholithiasis and cholelithiasis | |||

| Therapeutic splitting (pre- or intraoperatively) is recommended in patients diagnosed with choledocholithiasis and concurrent cholelithiasis (recommendation grade B, evidence level I, strong consensus). After successful endoscopic bile duct clearance, cholelithiasis should be treated by cholecystectomy, ideally within 72 h. A stone-free functioning gallbladder can be left in place (recommendation grade B, evidence level I, strong consensus). | In patients found to have stones in both gallbladder and bile duct, early laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be performed within 72 h after preoperative ERCP (moderate evidence, strong recommendation). | ERCP with stone extraction may be performed either before, during, or after cholecystectomy, with little discernible differences in morbidity and mortality and clearance rates similar to those for laparoscopic bile duct exploration (evidence level I, recommendation grade A). | |

| Surgical strategy | |||

| Laparoscopic surgery represents the standard procedure for cholecystectomy, both in the presence of symptomatic gallstones and in acute cholecystitis. Laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be carried out using the four-trocar technique (recommendation grade B, evidence level II, strong consensus). | Laparoscopic surgery represents the standard procedure for cholecystectomy, both in the presence of symptomatic gallstones and in acute cholecystitis (high evidence, strong recommendation). Laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be carried out using the four-trocar technique; two of the trocars should measure at least 10 mm in diameter, the other two at least 5 mm (very low evidence, weak recommendation). | Most patients with symptomatic cholelithiasis are suitable for laparoscopic cholecystectomy, provided they can tolerate general anesthesia and have no severe cardiopulmonary disease or other comorbidities that rule out surgery. Further indications are biliary dyskinesia, acute cholecystitis, and complications of choledocholithiasis (recommendation grade A, evidence level II). | Laparoscopic surgery can be carried out even in the presence of severe inflammation (grade III), provided the patient’s condition allows and there are no other contraindications. Besides the preoperative factors, the risk can be assessed on the basis of the intraoperative findings (evidence level D). According to the intraoperative findings, appropriate bail-out procedures should be chosen to prevent bile duct injury (recommendation grade 1, evidence level C). |

EASL, European Association for the Study of the Liver; ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography;

SAGES, Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons

Both the current German clinical practice guidelines and the EASL favor the four-trocar technique for laparoscopic cholecystectomy in order to decrease the risk of surgical complications. Sufficient experience must be demonstrated before selecting alternative approaches (e.g., the single port technique) (1, 2) (table 1).

Gallbladder concrements >3 cm, polyps >1 cm, and porcelain gallbladder bear a much higher risk of malignancy. In these circumstances, elective cholecystectomy is indicated even for asymptomatic cholelithiasis.

While gallbladder concrements >3 cm increase the risk of cancer tenfold, the risk in porcelain gallbladder is up to 62% (31). For polyps >1 cm the risk is around 50%.

Perioperative antibiotic prophylaxis is not necessary in normal elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Both the EASL recommendations and the SAGES guidelines confirm that only in high-risk patients (age >60 years, known diabetes mellitus, jaundice, acute biliary colic within the past 30 days; also in confirmed acute cholecystitis or cholangitis) can antibiotics potentially reduce the incidence of wound infection (1, 5).

Indication for treatment of cholelithiasis.

As a rule, treatment for cholelithiasis is indicated only in the presence of symptoms. There is usually no indication for cholecystectomy in asymptomatic patients unless they are found to have gallstones >3 cm, polyps >1 cm, or porcelain gallbladder.

Oncological resections involving the stomach and esophagus with systematic lymphadenectomy should be accompanied by simultaneous cholecystectomy. The risk of stone formation after oncological gastrectomy increases with the extent of lymphadenectomy. The mean proportion of patients that develop gallstones subsequent to oncological gastrectomy is 25%, rising to over 40% following extended lymphadenectomy.

In the context of bariatric surgery, cholecystectomy should be reserved for patients known to have gallstones. The only asymptomatic patients in whom simultaneous cholecystectomy should be performed are those undergoing major malresorptive small bowel interventions.

Acute cholecystitis is the most frequently occurring complication of gallstones. The spontaneous course of acute cholecystitis is mostly unfavorable. Studies have shown that more than a third of patients with conservative management of acute cholecystitis develop complications such as choledocholithiasis or biliary pancreatitis within 2 years (e1, e2). Therefore, any patient with confirmed acute cholecystitis who is suitable for surgery should undergo early cholecystectomy within 24 h after hospital admission to avoid later complications. Up to a few years ago conventional cholecystectomy was considered the standard treatment for acute cholecystitis, but now, owing to the growing expertise in laparoscopic surgery, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the new standard even for acute inflammation. An elevated complication rate of primarily laparoscopic procedures has not been confirmed (32).

Two-stage treatment.

Separate treatment of simultaneously detected cholelithiasis and choledocholithiasis is indicated. The first step is endoscopic removal of the bile duct stones, followed—ideally within 72 h—by cholecystectomy.

Thus the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery (EAES) guidelines advise laparoscopic treatment for abdominal emergencies. The SAGES guidelines, too, recommend primarily laparoscopic management of acute cholecystitis (5, 6). On the other hand, the Tokyo guidelines, last revised in 2018, state that a laparoscopic intervention should always be the aim in acute cholecystitis, regardless of its severity, so that how to continue can be decided on the basis of the intraoperative findings. Where visibility or access are poor, three bail-out procedures are recommended: conversion to open surgery, subtotal cholecystectomy, or the fundus-first technique, in which the gallbladder is detached in antegrade fashion starting at the fundus, in order to achieve safe separation of the infundibulum from the hepatoduodenal ligament (7).

Alternative procedures are endosonographically guided gallbladder drainage (EUS-GBD) and transpapillary gallbladder drainage. These methods have been evaluated in randomized trials and are now used by experienced investigators in specialized centers. For EUS-GBD in acute cholecystitis, successful results have recently been achieved especially with lumen-apposing metal stents (LAMS). The updated Tokyo guidelines recommend percutaneous drainage as the standard for surgical high-risk patients, but view EUS-GBD as an equivalent procedure in the hands of experienced endoscopists (e3).

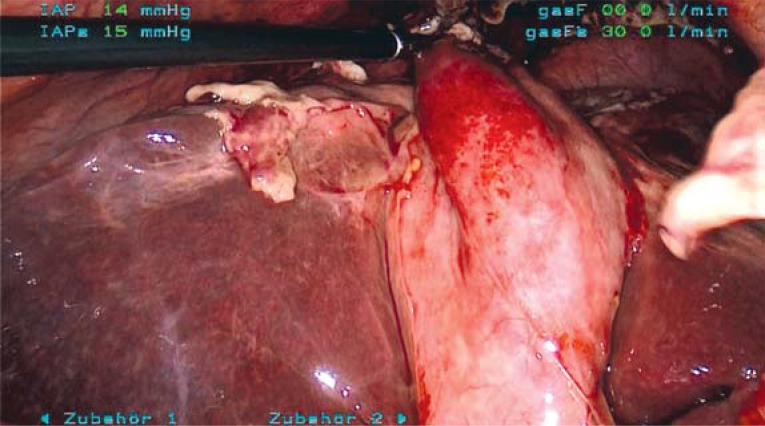

With regard to the optimal timing of surgery for acute cholecystitis, recent studies have shown that immediate intervention is beneficial. Therefore, laparoscopic cholecystectomy should be carried out within 24 h of the patient’s admission to the hospital (8, 33) (figure 3).

Figure 3.

Intraoperative view of acute cholecystitis

Routine antibiotic prophylaxis.

Routine antibiotic prophylaxis is not necessary for low-risk patients treated with elective laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

A retrospective study showed that treatment of acute cholecystitis with early cholecystectomy was associated with a shorter hospital stay (e4).

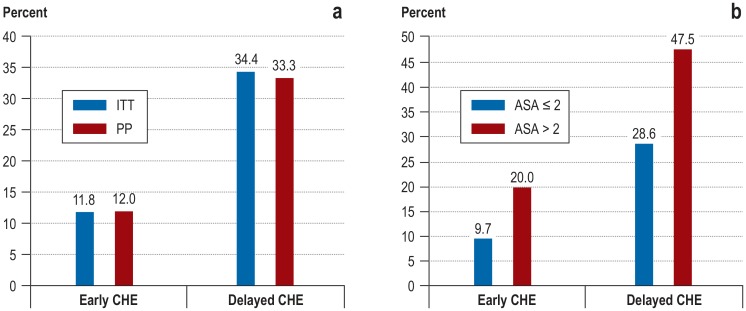

The largest prospective randomized trial on acute cholecystitis published to date is the ACDC Study (8, 9). Patients assigned the diagnosis “acute cholecystitis” were treated with laparoscopic cholecystectomy either within 24 h or electively following primary conservative treatement. The conversion rate was the same for both strategies, but the study found significant benefits for early cholecystectomy (figure 4).

Figure 4.

Results of the ACDC Study (8)

a) Proportion (%) of patients with relevant comorbidities within the first 75 days after study inclusion: early versus delayed cholecystectomy

b) Proportion (%) of ITT patients with ASA score ≤ 2 (healthy or mild systemic disease) or >2 (severe or life-threatening disease) at the end of the study after 75 days

ACDC, Acute Cholecystitis: Early Versus Delayed Cholecystectomy; ASA, American Society of Anesthesiologists; CHE, cholecystectomy; ITT, intention to treat; PP, per protocol

The rate of morbidity, for example, was 12% in the early cholecystectomy group but 33% in the initially conservatively treated group. The length of stay in hospital was also 50% lower (5.4 vs. 10.0 days) with early surgery (Figure 4a, b). In contrast, the Tokyo guidelines contain no clear recommendation as to when surgery should take place (10).

If postoperative examination of the gallbladder reveals carcinoma in situ (Tis) or mucosal cancer (T1a), no further surgery is required. If gallbladder cancer stage ≥ T1b is found, however, one should proceed to oncological resection and lymphadenectomy with curative intent (2).

Laparoscopic cholecystectomy can be carried out in every trimester of pregnancy if urgently indicated. A woman who shows symptoms of acute cholecystitis in the first trimester should undergo early elective surgery owing to the considerable risk of recurrence later in the pregnancy (2).

Current standard.

Up to a few years ago conventional cholecystectomy was considered the standard treatment for acute cholecystitis, but now, owing to the growing expertise in laparoscopic surgery, laparoscopic cholecystectomy is the new standard even for acute inflammation.

Choledocholithiasis detected on diagnostic imaging and causing symptoms such as colic, jaundice, or inflammation (so-called symptomatic choledocholithiasis) should be treated with endoscopic intervention. Asymptomatic bile duct stones often stay asymptomatic, but are routinely extracted in patients who undergo cholecystectomy. Antibiotic treatment should be started immediately in patients with obstructive, stone-related acute cholangitis. The timing of endoscopic treatment of the obstruction (stone extraction or drainage) depends on the degree of urgency, but the delay should never be longer than necessary; a patient showing signs of sepsis must be treated immediately. For patients who have biliary pancreatitis and suspected coexisting acute cholangitis, the EASL recommends administration of antibiotics followed, within 24 h, by ERC with sphincterotomy and stone extraction (1).

Simultaneously occurring choledocholithiasis and cholelithiasis should be treated separately. The standard procedure is preoperative endoscopic papillotomy (EPT) and stone extraction (Tables 1 and 2, Figure 2). If the transpapillary procedure fails, alternative interventional methods or a primarily surgical approach should be considered. With regard to primarily open conventional procedures, meta-analyses (34) have found that operative duct revision removes bile duct concrements more efficiently than preoperative ERC or EPT.

Table 2. Overview of the complications most frequently encountered with ERCP and laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

| Post-ERCP pancreatitis (%)* | Cholangitis (%) | Bleeding requiring treatment (%) | Perforation (duodenum or bile duct) (%) | Wound healing disorder (%) | Bile leakage (%) | Abscess (%) | |

| ERCP without papillotomy | 1.5 | 1.0–1.4 | 0.9 | 0.7 | – | – | – |

| ERCP with papillotomy | 3.9 | 1.0–1.4 | 2.6 | 2.2 | – | – | – |

| Elective cholecystectomy | – | – | – | – | 1.7–2.0 | 0.2–0.5 | 0.07 |

| Cholecystectomy in acute cholecystitis | – | 1.3 | – | – | 2.0 | 0.99 | 0.3 |

*Clinical pancreatitis with serum amylase level at least three times higher than normal at 24 h post ERCP.

ERCP, endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy.

Acute cholecystitis is an indication for early laparoscopic cholecystectomy, which should be carried out within 24 h of hospital admission.

Prior to endoscopic transpapillary stone extraction, papillotomy should be performed. If the bile duct stones are large, endoscopic papillary balloon dilatation (EPBD) can be carried out to improve their removal (35). If endoscopic stone extraction fails, adjuvant lithotripsy should take place, choosing between ESWL, intracorporeal laser lithotripsy, and electrohydraulic lithotripsy (EHL). In cases of coexisting cholelithiasis the surgical alternative should be discussed interdisciplinarily. If endoscopic transpapillary treatment is not successful and surgery is not an option, choledocholithiasis in symptomatic patients should be treated via the percutaneous transhepatic route. An alternative is EUS-guided bile duct drainage, which, compared with percutaneous transhepatic drainage, shows a greater clinical effect, involves fewer complications, and has a lower reintervention rate (e5). A further option in multimorbid patients is transpapillary insertion of a prosthesis. In patients with coexisting cholelithiasis, successful endoscopic removal of stones in the bile duct should be followed, preferably within 72 h and in any case during the same hospital stay, by cholecystectomy (27, 36, 37).

ACDC Study on acute cholecystitis.

The ACDC Study found significant benefits for early cholecystectomy with no difference in conversion rate.

In many patients with biliary pancreatitis, the stones are passed spontaneously. Urgent ERC with EPT is therefore not always necessary (38), although early clearance of an obstruction probably has a favorable influence on the course of acute biliary pancreatitis. If biliary pancreatitis is accompanied by cholestasis/jaundice and/or signs of cholangitis, ERC/papillotomy with stone extraction should be carried out as soon as possible, in the case of cholangitis within 24 h after admission. Patients with severe pancreatitis who are found to have choledocholithiasis but not cholangitis should undergo ERC with endoscopic papillotomy within 72 h of onset of symptoms. Cholecystectomy, if indicated, should be delayed until after resolution of the pancreatitis.

In uncomplicated, presumably biliary pancreatitis and in cholestasis/pancreatitis that is already subsiding, ERC need not be performed unless stones are detected on endosonography or MRC. Both the current German clinical practice guidelines and the EASL recommend carrying out cholecystectomy as soon as possible, because waiting for elective cholecystectomy is associated with a significant risk of a new attack of pancreatitis (39).

Symptomatic choledocholithiasis in pregnancy.

Even in pregnancy, symptomatic choledocholithiasis should be treated with endoscopic papillotomy and stone extraction.

Even in pregnancy, symptomatic choledocholithiasis should be treated with endoscopic papillotomy and stone extraction.

Further information on CME.

Participation in the CME certification program is possible only over the Internet: cme.aerzteblatt.de. This unit can be accessed until 24 May 2020. Submissions by letter, e-mail or fax cannot be considered.

-

The following CME units can still be accessed for credit:

„Hip Pain in Children“ (issue 5/2020) until 26 April 2020

„Vitamin Substitution Beyond Childhood“ (issue 1–2/2020) until 29 March 2020

„Acute Kidney Injury—A Frequently Underestimated Problem in Perioperative Medicine“ (issue 49/2019) until 1 March 2020

This article has been certified by the North Rhine Academy for Continuing Medical Education. Participants in the CME program can manage their CME points with their 15-digit “uniform CME number” (einheitliche Fortbildungsnummer, EFN), which is found on the CME card (8027XXXXXXXXXXX). The EFN must be stated during registration on www.aerzteblatt.de (“Mein DÄ”) or else entered in “Meine Daten,” and the participant must agree to communication of the results.

CME credit for this unit can be obtained via cme.aerzteblatt.de until 24 May 2020. Only one answer is possible per question. Please choose the most appropriate answer.

Question 1

When is pharmacological prevention of cholelithiasis with ursodeoxycholic acid appropriate?

In patients >60 years

At BMI of ≥ 24 kg/m2

Prior to resection of the terminal ileum

On the diagnosis of LPAC syndrome

In the presence of existing ulcerative colitis

Question 2

When is there an increased danger of biliary disease, particularly cholecystitis?

After administration of proton pump inhibitors

After intake of loop diuretics

With low-carbohydrate, high-fiber nutrition

In the first trimester of pregnancy

During hormone replacement therapy in the menopause

Question 3

Which of the following is a cardinal symptom of acute cholecystitis?

Left-sided upper abdominal pain

Unwanted weight loss

Positive Murphy sign

Jaundice

Shortness of breath

Question 4

Which of these imaging modalities should initially be used to exclude or confirm cholecystitis?

CT fluoroscopy

Transcutaneous sonography

Endosonography

Chest radiography

Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography

Question 5

What conclusion was reached by the authors of the ACDC Study, which compared conservative and surgical treatment of acute cholecystitis?

The morbidity rate is lower in the primarily conservatively treated group.

The length of stay in hospital is the same for both procedures.

Early cholecystectomy has significant benefits, while the conversion rate is the same for both strategies.

The complication rate is higher for early cholecystectomy.

Patients treated conservatively have a longer immobility phase.

Question 6

Which of the following methods possesses the highest sensitivity for the detection of choledocholithiasis, even with concrements <5 mm?

Transcutaneous sonography

Magnetic resonance cholangiography

Endosonography

Computed tomography

Abdominal radiography

Question 7

How many cholecystectomies are carried out each year in Germany for the treatment of cholelithiasis?

75 000 to 99 000

100 000 to 124 000

25 000 to 149 000

150 000 to 174 000

>175 000

Question 8

Within what time should successful endoscopic treatment of choledocholithiasis be followed by cholecystectomy?

3 days

4 days

5 days

6 days

7 days

Question 9

What proportion of patients have wound healing disorders after cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis?

1%

2%

3%

4%

5%

Question 10

Which of the following findings is associated with an elevated risk of the presence of gallbladder cancer?

Chronic obstipation

Gallstones <2 cm

Porcelain gallbladder

Polyps <1 cm

Chronic reflux esophagitis

► Participation is possible only via the Internet: cme.aerzteblatt.de

Acknowledgments

Translated from the original German by David Roseveare

Footnotes

Conflict of interest statement

The authors declare that no conflict of interest exists.

References

- 1.European Association for the Study of the Liver (EASL) EASL Clinical Practice Guidelines on the prevention, diagnosis and treatment of gallstones. J Hepatol. 2016;65:146–181. doi: 10.1016/j.jhep.2016.03.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gutt C, Jenssen C, Barreiros AP, et al. Aktualisierte S3-Leitlinie der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Gastroenterologie, Verdauungs- und Stoffwechselkrankheiten (DGVS) und der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Allgemein- und Viszeralchirurgie (DGAV) zur Prävention, Diagnostik und Behandlung von Gallensteinen. Z Gastroenterol. 2018;56:912–966. doi: 10.1055/a-0643-4420. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.NICE. Clinical Guideline 188; Gallstone disease: diagnosis and management. National Institute for Health and Care Excellence. 2014 [Google Scholar]

- 4.Gutt CN. Akute Cholezystitis: primär konservatives oder operatives Vorgehen? Chirurg. 2013;84:185–190. doi: 10.1007/s00104-012-2356-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Overby DW, Apelgren KN, Richardson W, Fanelli R. Society of American Gastrointestinal and Endoscopic Surgeons: SAGES guidelines for the clinical application of laparoscopic biliary tract surgery. Surg Endosc. 2010;24:2368–2386. doi: 10.1007/s00464-010-1268-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agresta F, Ansaloni L, Baiocchi GL, et al. Laparoscopic approach to acute abdomen from the Consensus Development Conference of the Societá Italiana di Chirurgia Endoscopica e nuove tecnologie (SICE), Associazione Chirurghi Ospedalieri Italiani (ACOI), Società Italiana di Chirurgia (SIC), Società die Chirurgia d´Urgenza e del Trauma (SICUT), Società Italiana di Chirurgia nell´Ospedalità Privata (SICOP), and the European Association for Endoscopic Surgery (EAES) Surg Endosc. 2012;26:2134–2164. doi: 10.1007/s00464-012-2331-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wakabayashi G, Iwashita Y, Hibi T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: Surgical management of acute cholecystitis: safe steps in laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25:73–86. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gutt CN, Encke J, Koninger J, et al. Acute cholecystitis: early versus delayed cholecystectomy, a multicenter randomized trial (ACDC study, NCT00447304) Ann Surg. 2013;258:385–393. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e3182a1599b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Weigand K, Köninger J, Encke J, Büchler MW, Stremmel W, Gutt CN. Acute cholecystitis—early laparoscopic surgery versus antibiotic therapy and delayed elective cholecystectomy: ACDC-study. Trials. 2007;8 doi: 10.1186/1745-6215-8-29. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Okamoto K, Suzuki K, Takada T, et al. Tokyo Guidelines 2018: Flowchart for the management of acute cholecystitis. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25:55–72. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Miller K, Hell E, Lang B, et al. Gallstone formation prophylaxis after gastric restrictive procedures for weight loss: a randomized double-blind placebo-controlled trial. Ann Surg. 2003;238:697–702. doi: 10.1097/01.sla.0000094305.77843.cf. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Grodstein F, Colditz GA, Stampfer MJ. Postmenopausal hormone use and cholecystectomy in a large prospective study. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:5–11. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Moller M, Gustafsson U, Rasmussen F, et al. Natural course vs interventions to clear common bile duct stones: data from the Swedish Registry for Gallstone Surgery and Endoscopic Retrograde Cholangiopancreatography (GallRiks) JAMA Surg. 2014;149:1008–1013. doi: 10.1001/jamasurg.2014.249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Shea JA, Berlin JA, Escarce JJ, et al. Revised estimates of diagnostic test sensitivity and specificity in suspected biliary tract disease. Arch Intern Med. 1994;154:2573–2581. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Götzky K, Landwehr P, Jähne J. Epidemiologie und Klinik der akuten Cholezystitis. Chirurg. 2013;84:179–184. doi: 10.1007/s00104-012-2355-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmed M, Diggory R. The correlation between ultrasonography and histology in the search for gallstones. Ann R Coll Surg Engl. 2011;93:81–83. doi: 10.1308/003588411X12851639107070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Altun E, Semelka RC, Elias J, et al. Acute cholecystitis: MR findings and differentiation from chronic cholecystitis. Radiology. 2007;244:174–183. doi: 10.1148/radiol.2441060920. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Benarroch-Gampel J, Boyd CA, Sheffield KM, et al. Overuse of CT in patients with complicated gallstone disease. J Am Coll Surg. 2011;213:524–530. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2011.07.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tonolini M, Ravelli A, Villa C, et al. Urgent MRI with MR cholangiopancreatography (MRCP) of acute cholecystitis and related complications: diagnostic role and spectrum of imaging findings. Emerg Radiol. 2012;19:341–348. doi: 10.1007/s10140-012-1038-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Soyer P, Hoeffel C, Dohan A, et al. Acute cholecystitis: quantitative and qualitative evaluation with 64-section helical CT. Acta Radiol. 2013;54:477–486. doi: 10.1177/0284185113475798. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.O‘Connor OJ, Maher MM. Imaging of cholecystitis. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2011;196:W367–W374. doi: 10.2214/AJR.10.4340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yokoe M, Takada T, Strasberg SM, et al. New diagnostic criteria and severity assessment of acute cholecystitis in revised Tokyo Guidelines. J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2012;19:578–585. doi: 10.1007/s00534-012-0548-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Pinto A, Reginelli A, Cagini L, et al. Accuracy of ultrasonography in the diagnosis of acute calculous cholecystitis: review of the literature. Crit Ultrasound J. 2013;5(1) doi: 10.1186/2036-7902-5-S1-S11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.ASGE Standards of Practice Committee. Maple JT, Ben-Menachem T, et al. The role of endoscopy in the evaluation of suspected choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2010;71:1–9. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2009.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meeralam Y, Al-Shammari K, Yaghoobi M. Diagnostic accuracy of EUS compared with MRCP in detecting choledocholithiasis: a meta-analysis of diagnostic test accuracy in head-to-head studies. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86:986–993. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2017.06.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Verma D, Kapedia A, Eisen GM, Adler DG. EUS vs MRCP for detection of choledocholithiasis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2006;64:248–254. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2005.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Boerma D, Rauws EA, Keulemans YC, et al. Wait-and-see policy or laparoscopic cholecystectomy after endoscopic sphincterotomy for bile-duct stones: a randomised trial. Lancet. 2002;360:761–765. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)09896-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Akriviadis EA, Hatzigavriel M, Kapnias D, Kirimlidis J, Markantas A, Garyfallos A. Treatment of biliary colic with diclofenac: a randomized, double-blind, placebo-controlled study. Gastroenterology. 1997;113:225–231. doi: 10.1016/s0016-5085(97)70099-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thistle JL, Cleary PA, Lachin JM, Tyor MP, Hersh T. The natural history of cholelithiasis: the National Cooperative Gallstone Study. Ann Intern Med. 1984;101:171–175. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-101-2-171. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lamberts MP, Kievit W, Ozdemir C, et al. Value of EGD in patients referred for cholecystectomy: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015;82:24–31. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2015.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Stephen AE, Berger DL. Carcinoma in the porcelain gallbladder: a relationship revisited. Surgery. 2001;129:699–703. doi: 10.1067/msy.2001.113888. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Stevens KA, Chi A, Lucas LC, et al. Immediate laparoscopic cholecystectomy for acute cholecystitis: no need to wait. Am J Surg. 2006;192:756–761. doi: 10.1016/j.amjsurg.2006.08.040. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Banz V, Gsponer TH, Candinas D, Güller U. Population-based analysis of 4113 patients with acute cholecystitis: Defining the optimal time-point for laparoscopic cholecystectomy. Ann Surg. 2011;254:964–970. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0b013e318228d31c. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Martin DJ, Vernon DR, Toouli J. Surgical versus endoscopic treatment of bile duct stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;2 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003327.pub2. CD003327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Weinberg BM, Shindy W, Lo S. Endoscopic balloon sphincter dilation (sphincteroplasty) versus sphincterotomy for common bile duct- stones. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2006;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD004890.pub2. CD004890. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lau JY, Leow CK, Fung TM, et al. Cholecystectomy or gallbladder in situ after endoscopic sphincterotomy and bile duct stone removal in Chinese patients. Gastroenterology. 2006;130:96–103. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2005.10.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reinders JS, Goud A, Timmer R, et al. Early laparoscopic cholecystectomy improves outcomes after endoscopic sphincterotomy for choledochocystolithiasis. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:2315–2320. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2010.02.052. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ayub K, Imada R, Slavin J. Endoscopic retrograde cholangiopancreatography in gallstone-associated acute pancreatitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2004;4 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD003630.pub2. CD003630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Da Costa DW, Bouwense SA, Schepers NJ, et al. Dutch Pancreatitis Study Group. Same-admission versus interval cholecystectomy for mild gallstone pancreatitis (PONCHO): a multicentre randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2015;386:1261–1268. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00274-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E1.de Mestral C, Rotstein OD, Laupacis A, Hoch JS, Zagorski B, Nathens AB. A population-based analysis of the clinical course of 10,304 patients with acute cholecystitis, discharged without cholecystectomy. Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute, St. Michael`s Hospital, Toronto, Ontario, Canada. J Trauma Acute Care Surg. 2013;74:26–30. doi: 10.1097/TA.0b013e3182788e4d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E2.Mora-Guzmán I, Di Martino M, Bonito AC, Jodra VV, Hernández SG, Martin-Perez E. Conservative management of gallstone disease in the elderly population: outcomes and recurrence. Scand J Surg. 2019 doi: 10.1177/1457496919832147. 1457496919832147. [Epub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E3.Mori Y, Itoi T, Baron TH, et al. TG18 management strategies for gall- bladder drainage in patients with acute cholecystitis: updated Tokyo guidelines 2018 (with videos) J Hepatobiliary Pancreat Sci. 2018;25:87–95. doi: 10.1002/jhbp.504. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E4.Gurusamy KS, Davidson C, Gluud C, Davidson BR. Early versus delayed laparoscopic cholecystectomy for people with acute cholecystitis. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2013;6 doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD005440.pub3. CD005440. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- E5.Sharaiha RZ, Khan MA, Kamal F, et al. Efficacy and safety of EUS-guided biliary drainage in comparison with percutaneous biliary drainage when ERCP fails: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85:904–991. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2016.12.023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]