Abstract

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) causes an increase in the mechanical loading imposed on the right ventricle (RV) that results in progressive changes to its mechanics and function. Here, we quantify the mechanical changes associated with PAH by assimilating clinical data consisting of reconstructed three-dimensional geometry, pressure, and volume waveforms, as well as regional strains measured in patients with PAH (n = 12) and controls (n = 6) within a computational modeling framework of the ventricles. Modeling parameters reflecting regional passive stiffness and load-independent contractility as indexed by the tissue active tension were optimized so that simulation results matched the measurements. The optimized parameters were compared with clinical metrics to find usable indicators associated with the underlying mechanical changes. Peak contractility of the RV free wall (RVFW) γRVFW,max was found to be strongly correlated and had an inverse relationship with the RV and left ventricle (LV) end-diastolic volume ratio (i.e., RVEDV/LVEDV) (RVEDV/LVEDV)+ 0.44, R2 = 0.77). Correlation with RV ejection fraction (R2 = 0.50) and end-diastolic volume index (R2 = 0.40) were comparatively weaker. Patients with with RVEDV/LVEDV > 1.5 had 25% lower γRVFW,max (P < 0.05) than that of the control. On average, RVFW passive stiffness progressively increased with the degree of remodeling as indexed by RVEDV/LVEDV. These results suggest a mechanical basis of using RVEDV/LVEDV as a clinical index for delineating disease severity and estimating RVFW contractility in patients with PAH.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY This article presents patient-specific data assimilation of a patient cohort and physical description of clinical observations.

Keywords: cardiac mechanics, contractility, data assimilation, patient-specific simulations, pulmonary arterial hypertension

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a complex disorder caused by an increased vascular resistance in the pulmonary arterial circulatory system. As a consequence, pressure becomes elevated in the pulmonary artery and the right ventricle (RV). Unlike systemic hypertension, PAH is difficult to detect in routine clinical examination, and the current gold standard for diagnosis is through invasive right heart catheterization (13). Because of the difficulty in detecting PAH, the current estimated prevalence of this disease (15 to 50 per million) is most likely underestimated (39, 40, 43). Perhaps also because of this difficulty, PAH is arguably less well studied compared with systemic hypertension. Existing treatments are largely confined to relieving the symptoms and attenuating the disease progression (28). As the disease progresses, the RV remodels both structurally and geometrically, becomes dysfunctional as a result, and eventually this progression leads to decompensated heart failure and death.

A significant part of our current understanding of the ventricular mechanical alterations due to PAH has been developed using animal models (2, 10, 15, 25, 57), which may not fully reproduce the pathologies found in humans (53). Human studies have so far been largely confined to measuring ventricular function of patients with PAH at the global level (54). Specifically, global RV contractility and wall stress are typically quantified using the maximal elastance (Emax) (12, 41) and Laplace’s law (46), respectively. However, the accuracy of Emax, defined as the maximum ratio of ventricular pressure to volume during the cardiac cycle, is highly dependent on the applied methodology. The gold standard for Emax estimation is through manipulation of venous return, but this is difficult to perform in practice (41). Estimates in patients are often confined to single beat methods, for which the accuracy has been questioned (30, 32). Similarly, the use of Laplace’s law is likely to be inaccurate when applied to the RV because of its irregular geometry (46). On the other hand, while magnetic resonance (MR) and echo imaging can quantify regional (including RV) myocardial strain or motion in vivo (11, 34, 60), strain is a load-dependent quantity and not truly a measure of myocardial contractility. As described by Reichek (50), the popular notion of equating myocardial contractility with (load dependent) strain measures is “off the mark [and] if contractility means anything, it is an expression of the ability of a given piece of myocardium to generate tension and shortening under any loading conditions.”

Computational modeling offers an opportunity to overcome these limitations through direct quantification of both passive and active ventricular mechanics under varying loading conditions. Such modeling has been used to assess left ventricular dynamics, and a small number of computational modeling studies have been conducted to investigate alterations of the RV mechanics in PAH (1, 7, 58). However, these studies are limited either by the use of nonhuman (rat) PAH data (7), the lack of consideration of patient-specific RV geometry (1), or the failure to consider the variability across patients with PAH (58). Consequently, there exists a gap in our current understanding of the changes in RV mechanics during the progression of PAH in humans. Here, we seek to narrow this gap by using a recently developed, gradient-based data-assimilation method (18) to evaluate patient-specific regional myocardial contractility and ventricular wall stresses from clinical PAH data. Specifically, we seek to answer the following three questions. First, is myocardial contractility, as indexed by the load-independent active tension generated by the tissue, altered in the left ventricular free wall (LVFW), right ventricular free wall (RVFW), and interventricular septum (SEPT) in PAH? Second, are ventricular wall stresses in the LV, septum, or in particular in the RV altered in PAH? Third, how are myocardial contractility and ventricular wall stresses associated with the progression of remodeling in PAH? We believe that answering these questions will help us to a better understanding the mechanical drivers of PAH progression and contribute to optimization of existing treatment strategies and the development of new therapies.

METHODS

Patient cohort and data processing.

Twelve patients with PAH were recruited in the study and underwent both cardiac magnetic resonance (CMR) scans and right heart catheterization (RHC) that were performed at rest using standard techniques. Pulmonary arterial hypertension was defined as having a mean pulmonary artery pressure (mPAP) ≥ 25 mmHg with normal pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (≤15 mmHg). The patients are from World Health Organization group 1 (pulmonary arterial hypertension) with the majority associated with congenital heart disease. Six human subjects who had no known cardiovascular disease or other comorbidities also underwent CMR scans and served as control in this study. Invasive hemodynamics measurements were not acquired in the control group. Demographics of the two study groups are summarized in Table 1. The protocol was approved by the Local Institutional Review Board, and informed consent was obtained from all subjects.

Table 1.

Demographics of the PAH patient and control groups

| Variables | Control | PAH | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | 6 | 12 | |

| Demographics | |||

| Age, yr | 52 ± 14 | 52 ± 11 | 0.989 |

| Sex, men/women | 1/5 | 2/10 | 0.755 |

| Weight, kg | 63.5 ± 16.9 | 61.2 ± 12.3 | 0.739 |

| Height, cm | 159 ± 8 | 161 ± 10 | 0.680 |

| Clinical exam | |||

| Body surface area, m2 | 1.67 ± 0.25 | 1.65 ± 0.20 | 0.873 |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 24.9 ± 4.0 | 23.6 ± 3.8 | 0.526 |

| 6-min walking test, m | N/A | 326 ± 134 | N/A |

| NT-ProBNP, pg/mL | N/A | 1,188 ± 715 | N/A |

| NYHA functional class I | N/A | 1 | N/A |

| NYHA functional class II | N/A | 8 | N/A |

| NYHA functional class III | N/A | 3 | N/A |

| NYHA functional class IV | N/A | 0 | N/A |

| Cardiac magnetic resonance | |||

| LV ejection fraction, % | 73 ± 7 | 58 ± 12 | 0.014 |

| LVEDV, mL | 93 ± 7 | 86 ± 30 | 0.574 |

| LVESV, mL | 25 ± 6 | 37 ± 21 | 0.198 |

| LVSV, mL | 68 ± 7 | 49 ± 14 | 0.009 |

| LVFW ES wall thickness, mm | 10.02 ± 1.25 | 10.87 ± 1.96 | 0.353 |

| LVFW ED wall thickness, mm | 5.42 ± 0.67 | 6.43 ± 1.29 | 0.093 |

| RV ejection fraction, % | 54 ± 11 | 37 ± 14 | 0.020 |

| RVEDV, mL | 103 ± 13 | 134 ± 72 | 0.322 |

| RVESV, mL | 47 ± 12 | 91 ± 68 | 0.148 |

| RVSV, mL | 56 ± 14 | 43 ± 13 | 0.095 |

| RVFW ES wall thickness, mm | 2.77 ± 0.24 | 6.22 ± 1.88 | <0.001 |

| RVFW ED wall thickness, mm | 1.75 ± 0.17 | 3.83 ± 0.61 | <0.001 |

| Septum ES wall thickness, mm | 9.21 ± 2.49 | 9.09 ± 2.75 | 0.926 |

| Septum ED wall thickness, mm | 6.13 ± 1.70 | 6.83 ± 2.20 | 0.508 |

| Hemodynamics | |||

| Heart rate, beats/min | 78 ± 16 | 88 ± 15 | 0.216 |

| Diastolic blood pressure, mmHg | 81 ± 15 | 75 ± 14 | 0.397 |

| Systolic blood pressure, mmHg | 140 ± 19 | 122 ± 27 | 0.170 |

| Peak LV pressure, mmHg | N/A | 129 ± 16 | N/A |

| Peak RV pressure, mmHg | N/A | 64 ± 15 | N/A |

| LV end-diastolic pressure, mmHg | N/A | 15 ± 2 | N/A |

| RV end-diastolic pressure, mmHg | N/A | 11 ± 5 | N/A |

| LV dP/dtmax, mmHg/s | N/A | 1,245 ± 309 | N/A |

| LV dP/dtmin, mmHg/s | N/A | −1,295 ± 275 | N/A |

| RV dP/dtmax, mmHg/s | N/A | 444 ± 273 | N/A |

| RV dP/dtmin, mmHg/s | N/A | −539 ± 232 | N/A |

| Cardiac output, L/min | 4.90 ± 1.16 | 3.98 ± 1.51 | 0.211 |

| Cardiac index, L·min−1·m−2 | 2.94 ± 0.57 | 2.39 ± 0.84 | 0.167 |

| Right atrial pressure, mmHg | N/A | 9 ± 9 | N/A |

| Mean pulmonary artery pressure, mmHg | N/A | 39 ± 9 | N/A |

| Pulmonary capillary wedge pressure, mmHg | N/A | 11 ± 3 | N/A |

| Systemic vascular resistance, dyn·s·cm−5 | N/A | 1,889 ± 751 | N/A |

| Pulmonary vascular resistance, dyn·s·cm−5 | N/A | 535 ± 254 | N/A |

| Pulmonary systemic flow ratio | N/A | 0.99 ± 0.1 | N/A |

| Pulmonary and systemic resistance ratio | N/A | 0.33 ± 0.15 | N/A |

Values are means ± SE; n, number of subjects. PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension; NT-ProBNP, NH2-terminal-pro-brain natriuretic peptide; NYHA, New York Heart Association; LV, left ventricular; RV, right ventricular; EDV, end-diastolic volume; ESV, end-systolic volume; SV, stroke volume; FW, free wall; ES, end systole; ED, end diastole; dP/dtmax and dP/dtmin, maximum and minimum first derivative of LV pressure, respectively; N/A, not applicable.

All subjects were imaged in a 3.0T Philips scanner (Philips-Ingenia; Philips Healthcare, Best, The Netherlands). Balanced steady-steady state free precession (bSSFP) end-expiratory breath-hold cine images were acquired in multiplanar short- and long-axis views. The typical imaging parameters were as follows: repetition time (TR):echo time (TE) ratio, 3/1 ms; matrix, 240 × 240; flip angle, 45°; slice thickness, 8 mm; pixel bandwidth, 1,776 Hz; field of view, 300 × 300 mm2; pixel spacing, 1.25 × 1.25 mm; and 30 frames/cardiac cycle for both the control group and PAH group.

Left ventricular pressure was measured through arterial access by left heart catheterization, and RV pressure was measured by right heart catheterization. Continuous LV pressure, RV pressure waveforms, and ECG signals were extracted from catheterization laboratory system and were aligned according to the simultaneously recorded ECG signals (R-R interval). These pressure waveforms were digitized using GetData Graph Digitizer (version 2.26). A total of three consecutive heart cycles were averaged to deal with the respiratory artifact if any. Pressure-volume (P-V) loops of the LV and RV of the patients with PAH were then reconstructed by synchronizing the LV and RV pressure waveforms measured from catheterization and volume waveforms, measured from the CMR images as described in Xi et al. (58). Because the ventricular pressure waveforms were not acquired in the control subjects, pressure waveforms acquired from normal humans in previous studies were used as surrogates to synchronize with the measured volume waveforms to reconstruct the P-V loops of each subject. Specifically, the mean normal RV pressure-waveform acquired from healthy human subjects in a previous study (49) was applied to all the control subjects. Based on a previous empirical study (29), a normal LV pressure-waveform with its end-systolic pressure scaled to be equal to 0.9 of the corresponding measured cuff pressure was applied to the control subjects. We have used this approach in our previous work (18, 58).

Regional circumferential strain (Ecc) and longitudinal strain Ell were estimated from the cine CMR images using a hyperelastic warping method, which has been used in previous studies to measure ventricular strains (22, 23, 44, 55, 60). The hyperelastic warping method has also been evaluated and shown to produce good intra- and interobserver agreement for estimating Ecc and Ell (60). Briefly, the biventricular geometry was segmented and reconstructed from the cine CMR images using MeVisLab (http://www.mevislab.de). The geometry was then partitioned into three regions consisting of the LVFW, RVFW, and SEPT (18, 60). The hyperelastic warping method was then applied to deform the reconstructed biventricular geometry from the template image into alignment with the corresponding object in the target image (22, 23). Normal strains in the circumferential and longitudinal directions at the LVFW, SEPT, and RVFW regions were computed from the displacement field using end diastole as the reference configuration. The circumferential and longitudinal directions in the biventricular unit were prescribed using a rule-based algorithm (8).

Construction of personalized models.

Personalized computational models of biventricular mechanics that fit the corresponding patient’s pressure, volume, and regional strain data were created using previously described methods (18). Briefly, the computational models were formulated based on classical large-deformation solid mechanics, and active contraction of the ventricular wall was incorporated by a multiplicative decomposition of the deformation gradient (6):

| (1) |

Here, F = I + ∇U is the total deformation gradient computed from the displacement field U, Fa is associated with an inelastic deformation resulting from the actively contracting muscle fibers, and is associated with the elastic deformation that preserves (kinematic) compatibility of the tissue under load. We employ the following form of Fa:

| (2) |

where f0 is the unit fiber direction in the reference configuration, and γ is a parameter that represents the relative active shortening strain along the muscle fibers, i.e., a measure of the local load-independent active tension generated by the tissue. Meanwhile, passive mechanics was modeled using a purely incompressible transversely isotropic hyperelastic material law (26) with an isochoric strain energy density given by

| (3) |

where a, b, af, and bf are material constants and are reduced (pseudo) invariants defined as

| (4) |

with being the volume preserving contribution to the elastic component of the right Cauchy Green strain tensor , and being the elastic volumetric deformation.

The ventricular base was fixed in the longitudinal direction and the biventricular geometry was anchored by constraining the epicardial surface using a Robin-type boundary condition with a linear spring of stiffness k = 0.5 kPa/cm (58). We note that these constraints still allow for apical-basal shortening in the simulations. Measured cavity pressure in the LV (plv) and RV (prv) were applied as Neumann conditions at the endocardial surfaces. The force-balance equations were solved using the finite element method implemented in FEniCS (36). A mixed formulation was used to enforce incompressibility of the elastic deformation (Je = 1) (26). Model results were tested for significance using Student’s t-tests with a chosen α-value of 0.05. Statistical power was computed for selected results to test the effects of the low sample size on the findings.

To separately determine the active and passive material properties of the computational model for each patient, the clinical measurements were divided into a passive phase and an active phase. Models were then optimized using the active and passive material parameters as control variables to minimize a weighted cost function based on the differences between model predictions and measurements of pressure, volume, and circumferential strain data as described previously (17, 18). Longitudinal strains were not included in the optimization due to the limited number of control parameters in the simulations but served as an independent measure of the final model fit as in our previous study (18). To solve the minimization problem, we applied a sequential quadratic programming algorithm (SQP) (31), which is a gradient-based optimization algorithm that requires the functional gradient of the cost function with respect to all the control variables. These gradients were efficiently estimated by solving an automatically derived adjoint equation using dolfin adjoint (16).

In the passive phase of the optimization, we used the parameter a in Eq. 3 as a control variable, allowing this parameter to vary while keeping all other parameters fixed. Parameter a scales the isotropic component of the transversely isotropic, strain-energy function and thereby characterizes the overall stiffness of the cardiac tissue. To capture regional differences in tissue stiffness, we introduce two different values of a: one associated with the LV (LVFW + SEPT, aLV) and one with the RVFW (aRVFW). These two parameters were allowed to vary independently from each other in the optimization. Similar to the procedure in Finsberg et al. (18), we first apply one iteration of the backward displacement method (9) to estimate an unloaded, stress-free configuration of the ventricles, thus neglecting residual stresses (21). The passive parameter was then determined by assimilating the passive-phase measurements, starting from an initial guess of aLV = aRVFW = 1.291 kPa. After fitting the model to the passive phase of the P-V curve and strain data, the parameters aLV and aRVFW were held fixed, and the relative active fiber shortening strain γ in Eq. 2 was chosen as the control variable for the active phase. While the chosen optimization method would in principle allow efficient estimation of any number of parameters [see Finsberg et al. (18)], the fact that the passive parameters are constant while the active parameters are time dependent motivates the two-step optimization procedure. We allowed γ associated with the LVFW (γLVFW), SEPT (γSEPT), and RVFW (γRVFW) to vary independently from each other to capture their spatial timing associated with active contraction. For each time point, we estimated γLVFW, γSEPT, and γRVFW to obtain their variation with time over a cardiac cycle. The spatially resolved, isotropic parameters a and γ-waveforms were estimated with different linear transmural variation of the myofiber helix angles varying from –α at the epicardium to +α at the endocardium, with α ranging from 30 to 80° (18). The set of parameters yielding the lowest mean square error between the predicted and measured strain and P-V data was taken to be the optimal one and used to post-process regional biventricular myofiber wall stresses σff.

RESULTS

Patient data and regional strains.

The control and PAH groups have comparable demographic characteristics, with the majority of the patients in the latter group (8/12) classified in New York Heart Association functional class II. In terms of hemodynamics, the PAH group had an mPAP of 39 ± 9 mmHg with a pulmonary capillary wedge pressure (PCWP) of 11 ± 3 mmHg. No differences in the systemic hemodynamics measurements (i.e., blood pressure) were detected between the two groups.

Evaluation of CMR images revealed that the PAH group had significantly (P < 0.05) reduced right ventricular ejection fraction (RVEF) (37 ± 14 vs. 54 ± 11%), increased RVFW thickness at ED (3.83 ± 0.61 vs. 1.75 ± 0.17 mm), and ES (6.22 ± 1.88 vs. 2.27 ± 0.24 mm) compared with the control group. Left ventricular ejection fraction (LVEF) and stroke volume (LVSV) were also significantly reduced in the PAH group compared with the control group (LVEF: 58 ± 12 vs. 73 ± 7%; and LVSV: 49 ± 14 vs. 68 ± 7 mL). Right ventricular end-diastolic volume (RVEDV) and right ventricular end-systolic volume (RVESV) were larger, but not statistically significant, in the PAH group. Although LV function, indexed by EF and SV, was significantly reduced in the patient group compared with the controls, only two of the patients were characterized with reduced ejection fraction (LVEF < 50%).

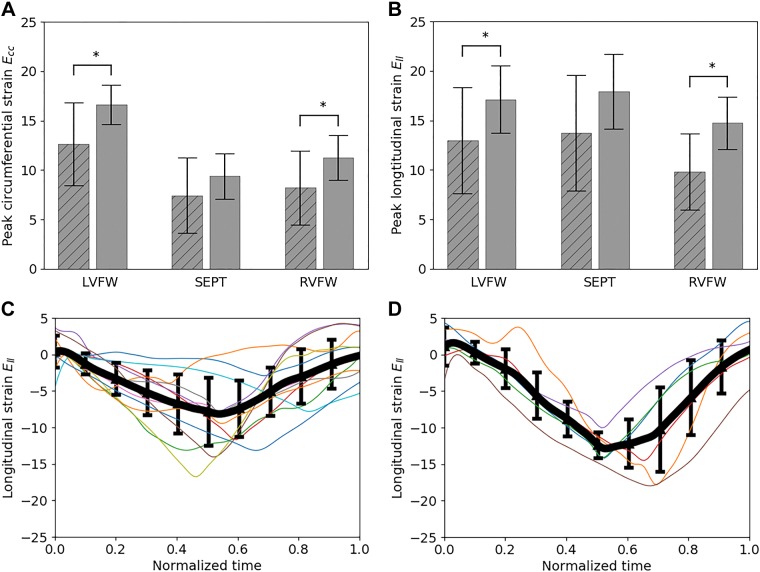

Absolute peak circumferential strain Ecc in the PAH group was significantly lower (one tailed, P < 0.05) than the control group at the LVFW (13 ± 4 vs. 17 ± 2%) and RVFW (8 ± 4 vs. 11 ± 2%) (Fig. 1). Similarly, peak longitudinal strain Ell in the PAH group was also significantly lower at the LVFW (13 ± 5 vs. 17 ± 3%) and RVFW (10 ± 4 vs. 15 ± 3%) compared with the control group. While both Ecc and Ell at the septum were lower in the PAH group than the control group, these reductions were not statistically significant (one tailed, P = 0.11 for Ecc and 0.05 for Ell).

Fig. 1.

Comparison of peak regional circumferential (A) and longitudinal (B) strains between control (unstriped) and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH; striped) groups; *P < 0.05, denoting that the latter value is statistically lower than the former. Time traces of right ventricular free wall (RVFW) longitudinal strain of the patients with PAH (C) and control subjects (D). Thick line denotes average, and error bar denotes standard deviation. Ecc, circumferential strain; Ell, longitudinal strain; LVFW, left ventricular free wall; SEPT, septum.

Model results and validation.

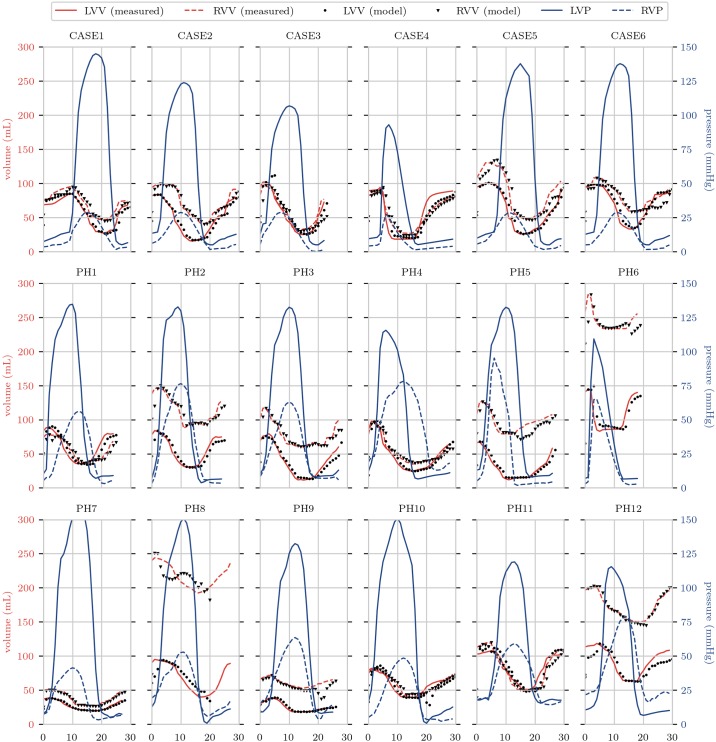

Optimized models were compared with measurements of cardiac volumes and strains for validation. For all cases, good temporal matching for pressure and volume was obtained, with Fig. 2 showing the simulated pressure and volume traces against measurements for all cases.

Fig. 2.

Pressure (blue) and volume (red) traces for all simulations. Solid pressure lines give loading conditions for the simulations, whereas solid red lines show measured volumes of the ventricles. Dots indicate optimized simulated volumes for the time points. LVV, left ventricular volume; RVV, right ventricular volume; LVP, left ventricular pressure; RVP, right ventricular pressure.

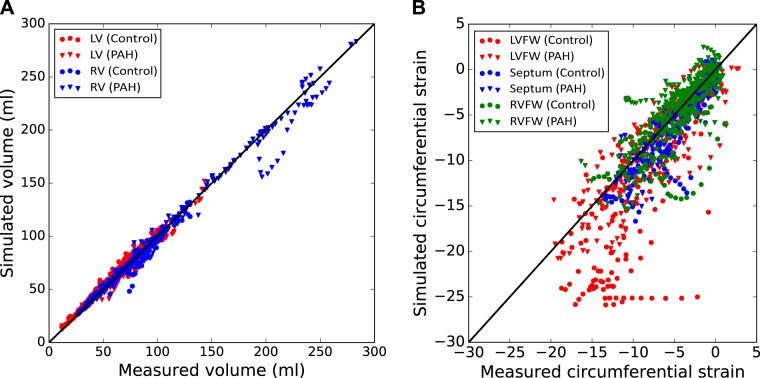

The overall fit of the LV and RV volumes in the patient-specific computational models is very good, with the simulation results closely agreeing with the measurements in the cardiac cycle (Fig. 3). The overall root mean square error (RMSE) of the fit is 3.89 mL for the RV and 6.6 mL for the LV. When compared with the volumes, the fit of the regional strains in the cardiac cycle shows significantly more scatter, especially at lower LV systolic strains. The RMSEs of the regional circumferential strain fit are 4.7% for the LVFW, 1.9% for the SEPT, and 2.6% for the RVFW. Meanwhile, serving as an independent measure of model fit, model prediction of longitudinal strains, which were not included in the optimization, has an RMSE of 6.2% for the LVFW, 6.2% for the SEPT, and 5.2% for the RVFW when compared with the measurements.

Fig. 3.

Overall data assimilation errors in the control (circle) and pulmonary arterial hypertension (diamond) populations. Comparison between measured and simulated volumes for both the right ventricular (RV; blue) and left ventricular (LV; red) (A) and circumferential strain for the LV free wall (LVFW; red), septum (green), and RV free wall X (RVFW; blue) at all cardiac time points (B). A y = x line is also plotted to show the zero-error reference.

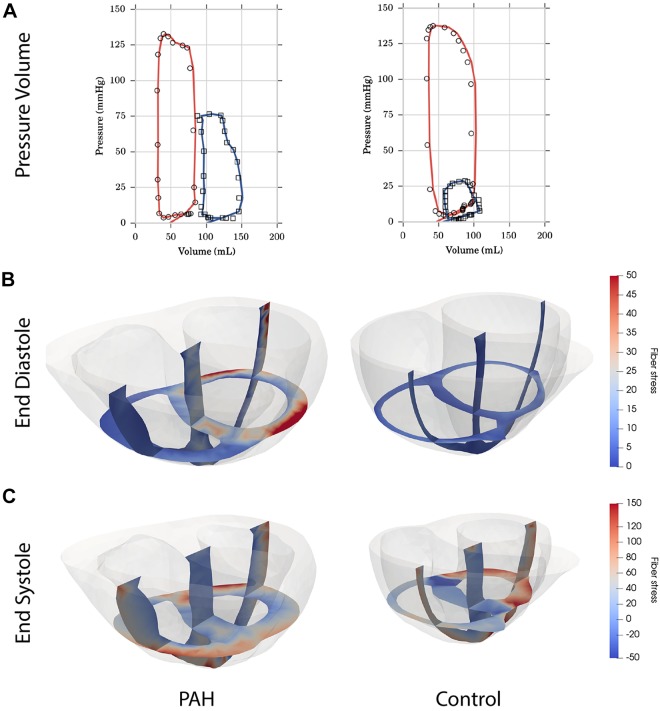

Figure 4 shows a comparison of model results for a single PAH patient and a healthy control. The figure illustrates the differences observed in the PAH group, including a shifted P-V loop of the RV, increased LV diastolic stress and RV systolic stress, and significant thickening of the RV. Note that the particular cross section shown in the figure tends to exaggerate the extent of RV wall thickening. The average RVFW thickness in patients with PAH was about two thirds of the septal thickness compared with about one third in the controls (Table 1).

Fig. 4.

Examples of simulation results from an extensively remodeled pulmonary hypertension patient, right ventricular (RV) end-diastolic volume-to-left ventricular (LV) end-diastolic volume ratio = 1.75, (left column) and a healthy control (right column). A: pressure-volume loop data (open markers) and simulations (solid lines) for the LV (red) and RV (blue). B: calculated fiber stresses at end diastole. C: calculated fiber stresses at end systole. PAH, pulmonary arterial hypertension.

Model results: contractility, stiffness, and stress.

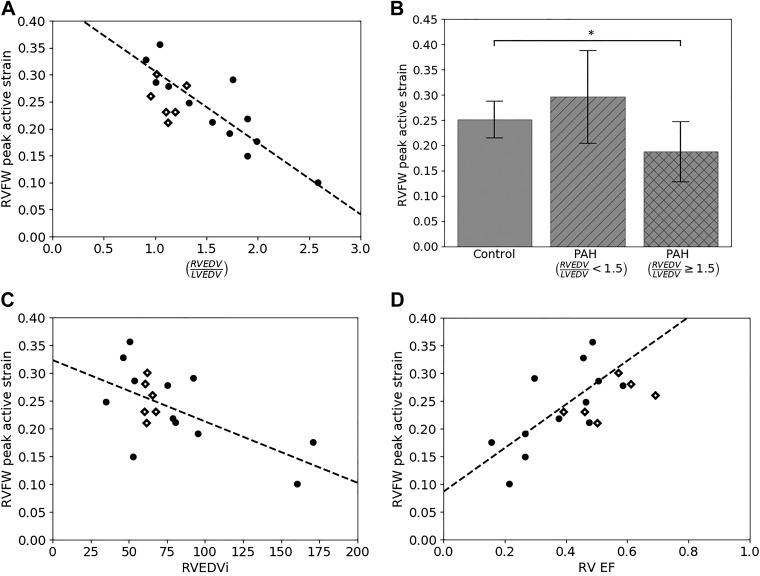

Regional contractility for the biventricular units was estimated using fitted values of the corresponding regional active strains γLVFW, γRVFW, and γSEPT during systole. Peak RVFW contractility γRVFW,max is not uniformly decreased in the PAH group, but instead presented a pattern with respect to the level of remodeling (Fig. 5). Using the ratio of RVEDV to LVEDV (i.e., RVEDV/LVEDV) as an indicator of remodeling, we found that RVEDV/LVEDV varies substantially in the PAH group (1.55 ± 0.50) but little in the control group (1.11 ± 0.12). With RVEDV/LVEDV = 1.5 (that is 3 SD from the mean value of the control group) serving as a threshold to delineate between patients with PAH and mild RV remodeling (RVEDV/LVEDV < 1.5) and those with severe RV remodeling (RVEDV/LVEDV ≥ 1.5), we found that in patients with PAH and mild RV remodeling, their peak RVFW contractility γRVFW,max is not significantly changed compared with the control group (P = 0.09). We note that the threshold RVEDV/LVEDV = 1.5 is approximately the midpoint for the range (1.27 ≤ RVEDV/LVEDV ≤ 1.69) proposed previously (5) to categorize “mild” RV dilation in patients with PAH. With increasing RVEDV/LVEDV, however, γRVFW,max decreases linearly so that γRVFW,max in patients with PAH and RVEDV/LVEDV ≥ 1.5 (severely remodeled PAH) is significantly less than that in the control group. The inverse linear relationship between γRVFW,max and RVEDV/LVEDV is strong and has a coefficient of determination R2 = 0.77. By comparison, γRVFW,max has a weaker linear relationship with RVEF (R2 = 0.50) and RVEDV index (RVEDVi) (R2 = 0.40). *P < 0.05.

Fig. 5.

Analysis of peak right ventricular free wall (RVFW) contractility γRVFW,max for control and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) groups. A: graphical depiction of γRVFW,max for both controls (diamonds) and patients (black dots) as a function of the ratio of right ventricular end-diastolic volume to left ventricular end-diastolic volume (RVEDV/LVEDV). Dashed line shows a linear fit to the patients with PAH group (γRVFW,max = –0.13 (RVEDV/LVEDV) +0.44, R2 = 0.77). B: average γRVFW,max for controls, patients with RVEDV/LVEDV < 1.5, and patients with RVEDV/LVEDV ≥ 1.5. C: linear fit of γRVFW,max with RVEDV index (RVEDVi; γRVFW,max = –0.001 (RVEDVi) +0.32, R2 = 0.40). D: linear fit of γRVFW,max with right ventricular ejection fraction (RVEF; γRVFW,max = 0.39 (RVEF) +0.09, R2 = 0.50). *P < 0.05.

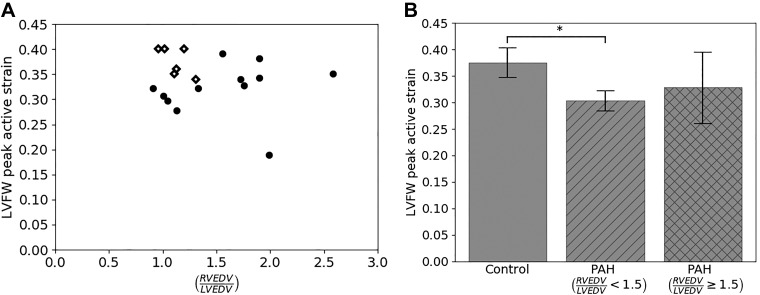

Peak contractility in the LVFW γLVFW,max, unlike γRVFW,max, did not exhibit any relationship with the level of remodeling as measured by RVEDV/LVEDV (Fig. 6). Specifically, we found that peak contractility in γLVFW,max is significantly smaller in the mildly remodeled PAH group with RVEDV/LVEDV < 1.5 (0.33 ± 0.02) compared with the control (0.38 ± 0.03) (P < 0.05). On the other hand, while the average γLVFW,max in the severely remodeled PAH group (0.33 ± 0.07) is decreased compared with the control group, that decrease is not statistically significant, possibly due to high standard deviation and low sample size (P = 0.14; power = 0.35).

Fig. 6.

Analysis of peak left ventricular free wall (LVFW) contractility γLVFW,max for control and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) groups. A: graphical depiction of peak LVFW contractility for both controls (diamonds) and patients (black dots) as a function of ratio of right ventricular end-diastolic volume to left ventricular end-diastolic volume (RVEDV/LVEDV). B: average γLVFW,max for controls, patients with RVEDV/LVEDV < 1.5, and patients with RVEDV/LVEDV ≥ 1.5. *P < 0.05.

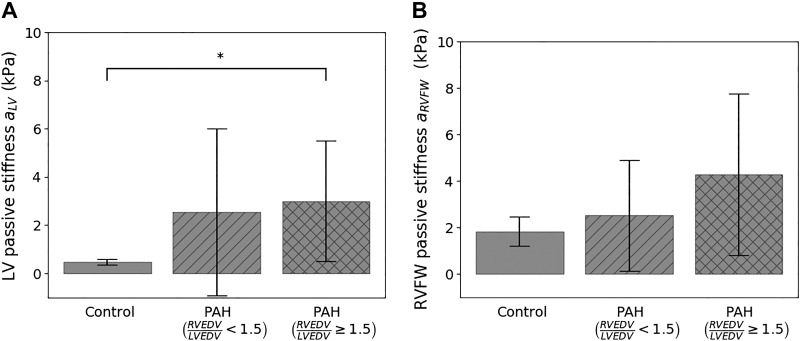

Fitted values of the regional material isotropic parameters aLV and aRVFW are measures of the tissue passive stiffness in the LVFW+SEPT and RVFW of the biventricular unit, respectively. Separating the fitted values in the PAH group based on the degree of remodeling (i.e., RVEDV/LVEDV) revealed a progressive increase in the mean value of aLV and aRVFW with remodeling (Fig. 7). The value aRVFW of one patient in the severely remodeled PAH group (RVEDV/LVEDV ≥ 1.5) is disregarded as it appears to be an outlier (Z score > 2, a = 36.78 kPa). In the severely remodeled PAH group, the mean value of aRVFW (4.3 ± 3.5 kPa) is 2.4 times higher than that of the control group (1.8 ± 0.6 kPa), but that increase is not significant, possibly due to the large standard deviation and low sample size in the former group (power = 0.34). On the other hand, the mean value of aLV in the severely remodeled PAH group (3.00 ± 2.5 kPa) is significantly higher (P < 0.05) than that of the control (0.48 ± 0.12 kPa).

Fig. 7.

Comparison of passive tissue stiffness parameter a between control and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) groups in the left ventricular (LV) free wall + septum (A) and right ventricular (RV) free wall (RVFW; B) regions. RVEDV/LVEDV, ratio of right ventricular end-diastolic volume to left ventricular end-diastolic volume. *P < 0.05.

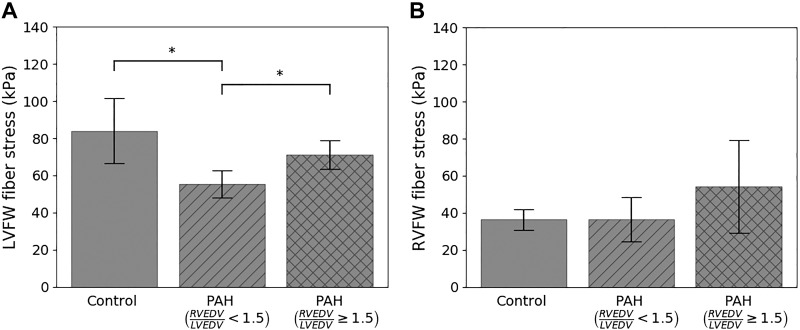

Using the data-assimilated computational models, we computed the peak regional wall stress in the myofiber direction (σff,max) (i.e., maximum myofiber load) (Fig. 8). We found σff,max at the RVFW is, on average, the same between the control (36.4 ± 5.7 kPa) and the mildly remodeled PAH (36.5 ± 12.0 kPa) groups. In the severely remodeled PAH group, however, the RVFW is on average 1.5 times larger (54.3 ± 25.1 kPa) than these two groups, but that difference is not significant (P = 0.14, power = 0.33) due to its large standard deviation. In comparison, the LVFW is significantly reduced in the mildly remodeled PAH group (55.4 ± 7.4 kPa) compared with the control group (84.0 ± 17.6 kPa). In the severely remodeled PAH group, the LVFW of two patients are disregarded since they appeared to be outliers with substantially large values (Z score > 2, σff,max = 544:1; 1659:9 kPa), which is likely due to the presence of local stress-concentration in the model. Peak myofiber stress at the LVFW in this group (71.22 ± 7.8 kPa) is significantly larger than the mildly remodeled PAH group but lower (not statistically significant) than the control.

Fig. 8.

Comparison of peak myofiber wall stress between control and pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) groups in the left ventricular free wall (LVFW; A) and right ventricular free wall (RVFW; B) regions. RVEDV/LVEDV, ratio of right ventricular end-diastolic volume to left ventricular end-diastolic volume. *P < 0.01, statistical significance between groups.

DISCUSSION

We have used a previously established data assimilation technique (17, 18) to quantify changes in regional myocardial properties and stresses in PAH based on measurements of P-V loops and myocardial strains from patients and a cohort of healthy subjects serving as control. The major finding of this study is a strong inverse linear relationship between the RVFW load-independent contractility, as indexed by the fitted model’s active strain parameter γRVFW,max and the degree of remodeling as indexed by RVEDV/LVEDV in patients with PAH. We have previously suggested that the contractility parameter γRVFW,max could possibly be a biomarker of ventricular failure (17), and its relationship to RVEDV/LVEDV (R2 = 0.77) is stronger than that with RVEF (R2 = 0.50) or RVEDVi (R2 = 0.40) in patients with PAH. We also found that RVFW contractility is increased by ~20% in patients with PAH when little remodeling is present (i.e., RVEDV/LVEDV < 1.5) but decreases linearly with increasing RVEDV/LVEDV.

The strong γRVFW,max-RVEDV/LVEDV relationship also suggests a mechanistic explanation for recent clinical findings that RVEDV/LVEDV is a better metric (with a higher sensitivity) than RVEDVi for identifying patients with PAH based on all-cause mortality (5), as well as for detecting RV enlargement (4). Besides PAH, this metric is also used for assessing RV dilation and indicating pulmonary valve replacement in patients who have tetralogy of Fallot (19, 35). There is, however, no other clear mechanistic basis for applying RVEDV/LVEDV to delineate the severity of PAH or electing surgery, other than a statistical association of this metric with clinical end points (5) or from clinical experience (35). Our finding suggests that the underlying reason why RVEDV/LVEDV is a better metric in determining PAH severity is because of its close association with RVFW contractility in PAH. Based on this relationship (Fig. 5A), the threshold of RVEDV/LVEDV of ~2 for distinguishing patients with PAH with severe RV dilation, as well as electing patients for pulmonary valve replacement, is associated with a reduction of RVFW contractility by ~30% from normal.

Fundamentally, our study also provides an insight into the changes in regional contractility during the progression of PAH. Our result suggests there is an increase in the RV contractility in early stages of PAH (RVEDV/LVEDV < 1.5), perhaps as a compensatory mechanism to maintain RVEF in response to the increased RV pressure, before it decreases as the disease progresses. The similarity in RVEF in patients with PAH with RVEDV/LVEDV < 1.5 (49 ± 5%) compared with normal (54 ± 11%) (Fig. 5) supports this theory. Because wall thickness is already accounted for geometrically in the computational models, the increase in RVFW contractility indicates that RV cardiomyocytes become hypercontractile in an attempt to normalize RVEF in the presence of increased pulmonary afterload at early stages of PAH. This finding is supported by a recent study which shows that the maximal tension of skinned myocytes of idiopathic patients with PAH is 28% higher than normal in early stages of disease with RVEF at 46 ± 7% (27), close to that found in patients with PAH with RVEDV/LVEDV < 1.5 in this study. Other than affecting the RV, we also found that LV contractility γLVFW in patients with PAH is reduced. This reduction is observed even in patients with PAH exhibiting little RV remodeling, suggesting that there is some early influence on LV function in this disease, a result broadly consistent with findings of reduced myocyte contractility in the LV of patients with PAH (37).

Besides contractility, we found that there is, on average, an increase in the LV and RV passive stiffness (reflected by aLV, aRVFW) with increased RVEDV/LVEDV in the PAH groups. While this increase is largely not statistically significant due to the large variance of the fitted parameter values, the result is consistent with experimental (47) and clinical (27) findings that PAH is associated with cardiac fibrosis and passive tissue stiffening. Interestingly, we also find that the peak LV fiber stress is reduced in patients with PAH with mild RV remodeling but is relatively unchanged in those with severe RV remodeling compared with the controls. This result could be due to changes in LV dynamics associated with a change in passive tissue stiffening and septal loading. Computation of the peak RV fiber stress using the fitted parameters, on the other hand, revealed that it is increased only in the severely remodeled patients with PAH, with RVEDV/LVEDV ≥ 1.5, although that increase is not statistically significant (P = 0.14, Fig. 8). Because myocardial wall stress is directly correlated with myocardial oxygen consumption (), this result suggests that is increased in the RV of patients with PAH with RVEDV/LVEDV ≥ 1.5 but less so in patients without substantial RV remodeling. When considered with our finding that RVFW contractility is reduced in patients with PAH with RVEDV/LVEDV ≥ 1.5, this result further suggests that coronary flow may not be sufficient to meet the increase in due to a higher workload in the RV, and as a result, ischemia develops in this cohort of patients producing a lower contractility. Our finding that RVEDV/LVEDV ≥ 1.5 may represent the threshold at which RV may become ischemic (with reduced contractility) is also consistent with clinical observations that RV ischemia may play a role in later stages of the disease (24, 42).

When compared with previous patient data assimilation techniques that have so far been only applied to the LV (17, 20, 33, 59) with a relatively small number of patients (n = ~6), we have shown that the semiautomatic data assimilation pipeline when applied to the biventricular unit is robust in regard to a sizable patient cohort (n = 12) that has features reflecting those found in the general heterogeneous PAH population. Specifically, patients with PAH recruited in this study had mPAP = 39 ± 9 mmHg and PCWP = 11 ± 3 mmHg, which falls within the clinical definition of this disease (mPAP ≥ 25 mmHg, and PCWP < 15 mmHg) (38). In terms of geometry and function, the patients with PAH had thicker RV wall, higher mean RVEDV, lower RV and LVEF, as well as significantly reduced longitudinal and circumferential strains at the RVFW and LVFW that are all consistent with previous clinical observations of this disease (3, 14, 45, 46, 48, 51, 52). The data assimilation process produces relatively few data outliers for both the control and patient groups and is able to fit the patient-specific ventricular volumes and regional strains well, especially considering the fact that only a small number of control variables is used in fitting the data.

Limitations and future directions.

Some limitations and challenges remain in regard to this study. One significant limitation is the lack of use of longitudinal strain data in the optimization, which resulted in relatively high error between the model and the measurements, especially in the septal region. We chose to use a minimal set of parameters in the optimization to prevent over fitting and to best discern between patient groups, but inaccuracy in the model in these regions may produce errors in these estimates. While we are able to fit the P-V loops and regional circumferential strains relatively well in this study, it will be useful to further explore the potential impact of the choice of the computational model and the control variables used to fit the patient data. This is particularly true in regard to chosen fiber angles. Although we saw little sensitivity to the overall results between using literature values and optimized fiber angles (see supplementary material: https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3357016), further study is needed to understand how best to incorporate variable fiber angles into patient-specific simulations. At the same time, the choice of boundary conditions may also influence the results (see supplementary material), and further work is needed to determine the most appropriate boundary conditions to be used for this type of analysis. It should also be noted that longitudinal strains are correlated to the circumferential strains through the incompressibility condition, and therefore the validation is not as strong as it would have been using an independent observation. In addition, even with this connection, the absolute errors in the longitudinal strain remain relatively large in our simulations. Second, the cohort size (n = 12) is fairly small, although it is still larger than many other patient-specific computational modeling studies. This limited sample size, especially with the need to further refine the patient group by level of remodeling, creates a somewhat underpowered study to investigate all the mechanical factors that could be important. Additional work is needed in larger cohorts to verify and refine some results, especially the relationship between LV and RV dynamics. For instance, our results indicated an increase in LV passive stiffness in patients with PAH, which is consistent with previous experimental and clinical findings. A sensitivity analysis (see supplementary material) of passive stiffness to LV diastolic pressure further supports that the increase is not a modeling artifact but a real difference between the groups. However, because of the large variability of fitted parameter values, the results are not statistically significant and will need to be confirmed in a larger cohort. Nevertheless, we are able to suggest a broad mechanistic explanation as to why some clinical indexes are better at characterizing PAH severity as well as features found during the progression of PAH, which are also supported by other clinical studies. A larger cohort needs to be considered in future studies. Third, we have applied surrogate pressure waveforms to the control subjects since RHC was not performed on them. Future studies can consider estimating pressures in control healthy subjects using Doppler echocardiography or including human subjects who have had false-positive diagnosis of PAH after undergoing RHC. Lastly, although an active strain formulation is able to provide information on the contraction dynamics and relative twitch strength, it is difficult to contextualize these results against other studies based on the active stress framework. In the supplementary material, we show that essential properties such as the force-length relationship are captured by the formulation of active strain, but additional work is needed to link active strain dynamics with the more physiologically derived active stress frameworks. Detailed studies of this kind will be important for comparing our findings with other studies and standards and would be particularly useful in optimizations that use dynamic information such as myofiber force generation over the entire twitch.

Conclusion.

In conclusion, we have shown that RVEDV/LVEDV is strongly associated with the RVFW load-independent contractility estimated from assimilating a computational model of active biventricular mechanics with clinical imaging and hemodynamics data acquired from patients with PAH and control subjects. Our study therefore suggests a mechanistic basis for using RVEDV/LVEDV as a noninvasive metric for assessing PAH severity as well as a noninvasive approach of estimating RV contractility from measurements of RVEDV/LVEDV.

GRANTS

This study was partially supported by Singapore Ministry of Health’s National Medical Research Council Singapore Grant NMRC/OFIRG/0018/2016 (to L. Zhong); Goh Cardiovascular Research Grant Duke-NUS-GCR/2013/0009 (to. L. Zhong); American Heart Association Scientist Development Grant 17SDG33370110 (to L. C. Lee); National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute Grant R01-HL-134841 (to L. C. Lee); and the Center for Cardiological Innovation (Research Council of Norway).

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

L.C.L. and S.T.W. conceived and designed research; X.Z., J.L.T., and L.Z. performed experiments; H.N.T.F., C.X., and M.G. analyzed data; L.C.L. and S.T.W. interpreted results of experiments; H.N.T.F., C.X., L.C.L., and S.T.W. prepared figures; L.C.L. and S.T.W. drafted manuscript; H.N.T.F., J.S.S., C.X., L.C.L., M.G., and S.T.W. edited and revised manuscript; and H.N.T.F., J.S.S., C.X., L.C.L., and S.T.W. approved final version of manuscript;

ENDNOTE

Supplementary material can be found at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3357016

REFERENCES

- 1.Acosta S, Puelz C, Rivière B, Penny DJ, Brady KM, Rusin CG. Cardiovascular mechanics in the early stages of pulmonary hypertension: a computational study. Biomech Model Mechanobiol 16: 2093–2112, 2017. doi: 10.1007/s10237-017-0940-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aguero J, Ishikawa K, Hadri L, Santos-Gallego C, Fish K, Hammoudi N, Chaanine A, Torquato S, Naim C, Ibanez B, Pereda D, García-Alvarez A, Fuster V, Sengupta PP, Leopold JA, Hajjar RJ. Characterization of right ventricular remodeling and failure in a chronic pulmonary hypertension model. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 307: H1204–H1215, 2014. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00246.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Altmayer SP, Losada N, Patel AR, Addetia K, Gomberg-Maitland M, Forfia PR, Han Y. Cmr rv size assessment should include RV to LV volume ratio. J Cardiovasc Magn Reson 17, S1: 394, 2015. doi: 10.1186/1532-429X-17-S1-P394. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altmayer SP, Patel AR, Addetia K, Gomberg-Maitland M, Forfia PR, Han Y. Cardiac MRI right ventricle/left ventricle (RV/LV) volume ratio improves detection of RV enlargement. J Magn Reson Imaging 43: 1379–1385, 2016. doi: 10.1002/jmri.25110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Altmayer SPL, Han QJ, Addetia K, Patel AR, Forfia PR, Han Y. Using all-cause mortality to define severe RV dilation with RV/LV volume ratio. Sci Rep 8: 7200, 2018. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-25259-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ambrosi D, Arioli G, Nobile F, Quarteroni A. Electromechanical coupling in cardiac dynamics: the active strain approach. SIAM J Appl Math 71: 605–621, 2011. doi: 10.1137/100788379. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avazmohammadi R, Mendiola EA, Soares JS, Li DS, Chen Z, Merchant S, Hsu EW, Vanderslice P, Dixon RA, Sacks MS. A computational cardiac model for the adaptation to pulmonary arterial hypertension in the rat. Ann Biomed Eng 47: 138–153, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s10439-018-02130-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Bayer JD, Blake RC, Plank G, Trayanova NA. A novel rule-based algorithm for assigning myocardial fiber orientation to computational heart models. Ann Biomed Eng 40: 2243–2254, 2012. doi: 10.1007/s10439-012-0593-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bols J, Degroote J, Trachet B, Verhegghe B, Segers P, Vierendeels J. A computational method to assess the in vivo stresses and unloaded configuration of patient-specific blood vessels. J Comput Appl Math 246: 10–17, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.cam.2012.10.034. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Borgdorff MA, Bartelds B, Dickinson MG, Steendijk P, de Vroomen M, Berger RM. Distinct loading conditions reveal various patterns of right ventricular adaptation. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 305: H354–H364, 2013. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00180.2013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bossone E, D’Andrea A, D’Alto M, Citro R, Argiento P, Ferrara F, Cittadini A, Rubenfire M, Naeije R. Echocardiography in pulmonary arterial hypertension: from diagnosis to prognosis. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 26: 1–14, 2013. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2012.10.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Brown KA, Ditchey RV. Human right ventricular end-systolic pressure-volume relation defined by maximal elastance. Circulation 78: 81–91, 1988. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.78.1.81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Champion HC, Michelakis ED, Hassoun PM. Comprehensive invasive and noninvasive approach to the right ventricle-pulmonary circulation unit: state of the art and clinical and research implications. Circulation 120: 992–1007, 2009. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.106.674028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.de Amorim Corrêa R, de Oliveira FB, Barbosa MM, Barbosa JAA, Carvalho TS, Barreto MC, Campos FTAF, Nunes MCP. Left ventricular function in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension: The role of two-dimensional speckle tracking strain. Echocardiography 33: 1326–1334, 2016. doi: 10.1111/echo.13267. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faber MJ, Dalinghaus M, Lankhuizen IM, Steendijk P, Hop WC, Schoemaker RG, Duncker DJ, Lamers JM, Helbing WA. Right and left ventricular function after chronic pulmonary artery banding in rats assessed with biventricular pressure-volume loops. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 291: H1580–H1586, 2006. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00286.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Farrell PE, Ham DA, Funke SW, Rognes ME. Automated derivation of the adjoint of high-level transient finite element programs. SIAM J Sci Comput 35: C369–C393, 2013. doi: 10.1137/120873558. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Finsberg H, Balaban G, Ross S, Håland TF, Odland HH, Sundnes J, Wall S. Estimating cardiac contraction through high resolution data assimilation of a personalized mechanical model. J Comput Sci 24: 85–90, 2018a. doi: 10.1016/j.jocs.2017.07.013. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Finsberg H, Xi C, Tan JL, Zhong L, Genet M, Sundnes J, Lee LC, Wall ST. Efficient estimation of personalized biventricular mechanical function employing gradient-based optimization. Int J Numer Methods Biomed Eng 34: e2982, 2018b. doi: 10.1002/cnm.2982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Frigiola A, Tsang V, Bull C, Coats L, Khambadkone S, Derrick G, Mist B, Walker F, van Doorn C, Bonhoeffer P, Taylor AM. Biventricular response after pulmonary valve replacement for right ventricular outflow tract dysfunction: is age a predictor of outcome? Circulation 118, Suppl: S182–S190, 2008. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.107.756825. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Genet M, Chuan Lee L, Ge L, Acevedo-Bolton G, Jeung N, Martin A, Cambronero N, Boyle A, Yeghiazarians Y, Kozerke S, Guccione JM. A novel method for quantifying smooth regional variations in myocardial contractility within an infarcted human left ventricle based on delay-enhanced magnetic resonance imaging. J Biomech Eng 137: 081009, 2015a. doi: 10.1115/1.4030667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Genet M, Rausch MK, Lee LC, Choy S, Zhao X, Kassab GS, Kozerke S, Guccione JM, Kuhl E. Heterogeneous growth-induced prestrain in the heart. J Biomech 48: 2080–2089, 2015b. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiomech.2015.03.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Genet M, Stoeck CT, von Deuster C, Lee LC, Kozerke S. Equilibrated warping: Finite element image registration with finite strain equilibrium gap regularization. Med Image Anal 50: 1–22, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2018.07.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Genet M, Stoeck C, von Deuster C, Lee LC, Guccione J, Kozerke S.. Finite element digital image correlation for cardiac strain analysis from 3d whole-heart tagging. ISMRM 24rd Annual Meeting and Exhibition, 2016 Singapore, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gómez A, Bialostozky D, Zajarias A, Santos E, Palomar A, Martínez ML, Sandoval J. Right ventricular ischemia in patients with primary pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 38: 1137–1142, 2001. doi: 10.1016/S0735-1097(01)01496-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hill MR, Simon MA, Valdez-Jasso D, Zhang W, Champion HC, Sacks MS. Structural and mechanical adaptations of right ventricle free wall myocardium to pressure overload. Ann Biomed Eng 42: 2451–2465, 2014. doi: 10.1007/s10439-014-1096-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Holzapfel GA, Ogden RW. Constitutive modelling of passive myocardium: a structurally based framework for material characterization. Philos Trans A Math Phys Eng Sci 367: 3445–3475, 2009. doi: 10.1098/rsta.2009.0091. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hsu S, Kokkonen-Simon KM, Kirk JA, Kolb TM, Damico RL, Mathai SC, Mukherjee M, Shah AA, Wigley FM, Margulies KB, Hassoun PM, Halushka MK, Tedford RJ, Kass DA. Right ventricular myofilament functional differences in humans with systemic sclerosis-associated versus idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 137: 2360–2370, 2018. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.033147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Jais X, Bonnet D. Treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. [French.] Presse Med 39, Suppl 1: 1S22–1S32, 2010. doi: 10.1016/S0755-4982(10)70004-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kelly RP, Ting CT, Yang TM, Liu CP, Maughan WL, Chang MS, Kass DA. Effective arterial elastance as index of arterial vascular load in humans. Circulation 86: 513–521, 1992. doi: 10.1161/01.CIR.86.2.513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Kjørstad KE, Korvald C, Myrmel T. Pressure-volume-based single-beat estimations cannot predict left ventricular contractility in vivo. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 282: H1739–H1750, 2002. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00638.2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kraft D. A software package for sequential quadratic programming. Forschungsbericht-Deutsche Forschungs-und Versuchsanstalt fur Luft-und Raumfahrt, 1988. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Lambermont B, Segers P, Ghuysen A, Tchana-Sato V, Morimont P, Dogne J-M, Kolh P, Gerard P, D’Orio V. Comparison between single-beat and multiple-beat methods for estimation of right ventricular contractility. Crit Care Med 32: 1886–1890, 2004. doi: 10.1097/01.CCM.0000139607.38497.8A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lee LC, Wenk JF, Klepach D, Zhang Z, Saloner D, Wallace AW, Ge L, Ratcliffe MB, Guccione JM. A novel method for quantifying in-vivo regional left ventricular myocardial contractility in the border zone of a myocardial infarction. J Biomech Eng 133: 094506, 2011. doi: 10.1115/1.4004995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Leng S, Jiang M, Zhao X-D, Allen JC, Kassab GS, Ouyang R-Z, Tan J-L, He B, Tan R-S, Zhong L. Three-dimensional tricuspid annular motion analysis from cardiac magnetic resonance feature-tracking. Ann Biomed Eng 44: 3522–3538, 2016. doi: 10.1007/s10439-016-1695-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Lindsey CW, Parks WJ, Kogon BE, Sallee D 3rd, Mahle WT. Pulmonary valve replacement after tetralogy of Fallot repair in preadolescent patients. Ann Thorac Surg 89: 147–151, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2009.07.039. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Logg A, Mardal KA, Wells G. Automated Solution of Differential Equations by the Finite Element Method: The FEniCS Book. Springer Science & Business Media, vol 84, 2012. [Google Scholar]

- 37.Manders E, Bogaard H-J, Handoko ML, van de Veerdonk MC, Keogh A, Westerhof N, Stienen GJ, Dos Remedios CG, Humbert M, Dorfmüller P, Fadel E, Guignabert C, van der Velden J, Vonk-Noordegraaf A, de Man FS, Ottenheijm CA. Contractile dysfunction of left ventricular cardiomyocytes in patients with pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 64: 28–37, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.04.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.McLaughlin VV, Archer SL, Badesch DB, Barst RJ, Farber HW, Lindner JR, Mathier MA, McGoon MD, Park MH, Rosenson RS, Rubin LJ, Tapson VF, Varga J, Harrington RA, Anderson JL, Bates ER, Bridges CR, Eisenberg MJ, Ferrari VA, Grines CL, Hlatky MA, Jacobs AK, Kaul S, Lichtenberg RC, Lindner JR, Moliterno DJ, Mukherjee D, Pohost GM, Rosenson RS, Schofield RS, Shubrooks SJ, Stein JH, Tracy CM, Weitz HH, Wesley DJ; ACCF/AHA . A report of the American college of cardiology foundation task force on expert consensus documents and the American heart association. Circulation 119: 2250–2294, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.McLaughlin VV, McGoon MD. Pulmonary arterial hypertension. Circulation 114: 1417–1431, 2006. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.104.503540. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mocumbi AO, Thienemann F, Sliwa K. A global perspective on the epidemiology of pulmonary hypertension. Can J Cardiol 31: 375–381, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.cjca.2015.01.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Naeije R, Brimioulle S, Dewachter L. Biomechanics of the right ventricle in health and disease (2013 Grover Conference series). Pulm Circ 4: 395–406, 2014. doi: 10.1086/677354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Naeije R, Manes A. The right ventricle in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Eur Respir Rev 23: 476–487, 2014. doi: 10.1183/09059180.00007414. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Peacock A, Murphy N, McMurray J, Caballero L, Stewart S. An epidemiological study of pulmonary arterial hypertension in scotland. Eur Respir J 30: 104–109, 2007. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00092306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Phatak NS, Maas SA, Veress AI, Pack NA, Di Bella EV, Weiss JA. Strain measurement in the left ventricle during systole with deformable image registration. Med Image Anal 13: 354–361, 2009. doi: 10.1016/j.media.2008.07.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Puwanant S, Park M, Popović ZB, Tang WH, Farha S, George D, Sharp J, Puntawangkoon J, Loyd JE, Erzurum SC, Thomas JD. Ventricular geometry, strain, and rotational mechanics in pulmonary hypertension. Circulation 121: 259–266, 2010. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.108.844340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quaife RA, Chen MY, Lynch D, Badesch DB, Groves BM, Wolfel E, Robertson AD, Bristow MR, Voelkel NF. Importance of right ventricular end-systolic regional wall stress in idiopathic pulmonary arterial hypertension: a new method for estimation of right ventricular wall stress. Eur J Med Res 11: 214–220, 2006. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Rain S, Andersen S, Najafi A, Gammelgaard Schultz J, da Silva Gonçalves Bós D, Handoko ML, Bogaard HJ, Vonk-Noordegraaf A, Andersen A, van der Velden J, Ottenheijm CA, de Man FS. Right ventricular myocardial stiffness in experimental pulmonary arterial hypertension: relative contribution of fibrosis and myofibril stiffness. Circ Heart Fail 9: e002636, 2016. doi: 10.1161/CIRCHEARTFAILURE.115.002636. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Rajagopal S, Forsha DE, Risum N, Hornik CP, Poms AD, Fortin TA, Tapson VF, Velazquez EJ, Kisslo J, Samad Z. Comprehensive assessment of right ventricular function in patients with pulmonary hypertension with global longitudinal peak systolic strain derived from multiple right ventricular views. J Am Soc Echocardiogr 27: 657–665.e3, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.echo.2014.02.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Redington AN, Gray HH, Hodson ME, Rigby ML, Oldershaw PJ. Characterisation of the normal right ventricular pressure-volume relation by biplane angiography and simultaneous micromanometer pressure measurements. Br Heart J 59: 23–30, 1988. doi: 10.1136/hrt.59.1.23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Reichek N. Right ventricular strain in pulmonary hypertension: flavor du jour or enduring prognostic index? Circ Cardiovasc Imaging 6: 609–611, 2013. doi: 10.1161/CIRCIMAGING.113.000936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Shehata ML, Harouni AA, Skrok J, Basha TA, Boyce D, Lechtzin N, Mathai SC, Girgis R, Osman NF, Lima JA, Bluemke DA, Hassoun PM, Vogel-Claussen J. Regional and global biventricular function in pulmonary arterial hypertension: a cardiac MR imaging study. Radiology 266: 114–122, 2013. doi: 10.1148/radiol.12111599. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Smith BC, Dobson G, Dawson D, Charalampopoulos A, Grapsa J, Nihoyannopoulos P. Three-dimensional speckle tracking of the right ventricle: toward optimal quantification of right ventricular dysfunction in pulmonary hypertension. J Am Coll Cardiol 64: 41–51, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2014.01.084. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Stenmark KR, Meyrick B, Galie N, Mooi WJ, McMurtry IF. Animal models of pulmonary arterial hypertension: the hope for etiological discovery and pharmacological cure. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 297: L1013–L1032, 2009. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00217.2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Trip P, Rain S, Handoko ML, van der Bruggen C, Bogaard HJ, Marcus JT, Boonstra A, Westerhof N, Vonk-Noordegraaf A, de Man FS. Clinical relevance of right ventricular diastolic stiffness in pulmonary hypertension. Eur Respir J 45: 1603–1612, 2015. doi: 10.1183/09031936.00156714. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Veress AI, Gullberg GT, Weiss JA. Measurement of strain in the left ventricle during diastole with cine-MRI and deformable image registration. J Biomech Eng 127: 1195–1207, 2005. doi: 10.1115/1.2073677. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Wang Z, Schreier DA, Hacker TA, Chesler NC. Progressive right ventricular functional and structural changes in a mouse model of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Physiol Rep 1: e00184, 2013. doi: 10.1002/phy2.184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Xi C, Latnie C, Zhao X, Tan JL, Wall ST, Genet M, Zhong L, Lee LC. Patient-specific computational analysis of ventricular mechanics in pulmonary arterial hypertension. J Biomech Eng 138: 111001, 2016. doi: 10.1115/1.4034559. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Xi J, Lamata P, Shi W, Niederer S, Land S, Rueckert D, Duckett SG, Shetty AK, Rinaldi CA, Razavi R, Smith N. An automatic data assimilation framework for patient-specific myocardial mechanical parameter estimation. In: International Conference on Functional Imaging and Modeling of the Heart New York: Springer, 2011, p. 392–400. [Google Scholar]

- 60.Zou H, Xi C, Zhao X, Koh AS, Gao F, Su Y, Tan RS, Allen J, Lee LC, Genet M, Zhong L. Quantification of biventricular strains in heart failure with preserved ejection fraction patient using hyperelastic warping method. Front Physiol 9: 1295, 2018. doi: 10.3389/fphys.2018.01295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]