Abstract

Nitric oxide (NO) is known to exert inhibitory control on mitochondrial respiration in the heart and brain. Evidence supports the presence of NO synthase (NOS) in the mitochondria (mtNOS) of cells; however, the functional role of mtNOS in the regulation of mitochondrial respiration is unclear. Our objective was to examine the effect of NOS inhibitors on mitochondrial respiration and protein S-nitrosylation. Freshly isolated cardiac and brain nonsynaptosomal mitochondria were incubated with selective inhibitors of neuronal (nNOS; ARL-17477, 1 µmol/L) or endothelial [eNOS; N5-(1-iminoethyl)-l-ornithine, NIO, 1 µmol/L] NOS isoforms. Mitochondrial respiratory parameters were calculated from the oxygen consumption rates measured using Agilent Seahorse XFe24 analyzer. Expression of NOS isoforms in the mitochondria was confirmed by immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis. In addition, we determined the protein S-nitrosylation by biotin-switch method followed by immunoblotting. nNOS inhibitor decreased the state IIIu respiration in cardiac mitochondria and both state III and state IIIu respiration in brain mitochondria. In contrast, eNOS inhibitor had no effect on the respiration in the mitochondria from both heart and brain. Interestingly, NOS inhibitors reduced the levels of protein S-nitrosylation only in brain mitochondria, but nNOS and eNOS immunoreactivity was observed in the cardiac and brain mitochondrial lysates. Thus, the effects of NOS inhibitors on S-nitrosylation of mitochondrial proteins and mitochondrial respiration confirm the existence of functionally active NOS isoforms in the mitochondria. Notably, our study presents first evidence of the positive regulation of mitochondrial respiration by mitochondrial nNOS contrary to the current dogma representing the inhibitory role attributed to NOS isoforms.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Existence and the role of nitric oxide synthases in the mitochondria are controversial. We report for the first time that mitochondrial nNOS positively regulates respiration in isolated heart and brain mitochondria, thus challenging the existing dogma that NO is inhibitory to mitochondrial respiration. We have also demonstrated reduced protein S-nitrosylation by NOS inhibition in isolated mitochondria, supporting the presence of functional mitochondrial NOS.

Keywords: eNOS, mitochondrial nitric oxide synthase, mitochondrial respiration, oxygen consumption rate, nNOS

INTRODUCTION

Nitric oxide (NO) plays a critical role in cardiovascular and cerebrovascular physiology and pathophysiology (3, 23, 26). Cellular NO is primarily produced by NO synthases (NOS) (7). Three isoforms of NOS have been known, including neuronal NOS (nNOS or NOS1), endothelial NOS (eNOS or NOS3), and the induced NOS (iNOS or NOS2) (23). Both endogenous NO derived from NOS isoforms, and exogenous NO released by NO donors have been shown to exert inhibitory effect on mitochondrial respiration by targeting electron transport chain complexes (ETC) (1, 9). Although molecular identity of mitochondrial NOS (mtNOS) is controversial and mtNOS has been shown to impact mitochondrial function in isolated mitochondria, its regulation of mitochondrial respiration is poorly understood (9, 15). Furthermore, NO promotes S-nitrosylation of proteins by addition of NO moiety to the thiol groups of cysteine (6). Protein S-nitrosylation, attributed mostly to cytosolic NOSs, regulates physiological functions as well as the pathological signaling involved in cardiac protection and neurodegenerative diseases (6, 18, 24). However, mtNOS-induced protein S-nitrosylation was understudied. Thus, we hypothesize that NOS inhibitors regulate the respiration in the isolated mouse cardiac and brain mitochondria via altering the NOS-mediated S-nitrosylation of the mitochondrial proteins. Although regulation of mitochondrial mitochondria in the heart and brain has been known to be different, we employed the mitochondria from both the tissues to validate our novel methods and findings.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Reagents.

Sucrose, mannitol, ethylene glycol-bis (2-aminoethylether)-N,N,N′,N′-tetraacetic acid (EGTA), 4-(2-hydroxyethyl)-1-piperazineethanesulfonic acid (HEPES), bovine serum albumin (BSA) fatty acid-free, Percoll, sodium pyruvate, malate, ADP sodium, antimycin A, rotenone, N-[4-[2-[[(3-chlorophenyl) methyl]amino]ethyl]phenyl]-2-thiophenecarboximidamide dihydrochloride hydrate (ARL-17477), and Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME). All the above-mentioned chemicals were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO. N5-(1-iminoethyl)-l-ornithine (NIO) dihydrochloride and FCCP were purchased from Cayman Chemicals, Ann Arbor, MI. Dihydroethidium and rhodamine 123 were purchased from Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA.

Isolation of mouse cardiac and brain nonsynaptosomal mitochondria.

All experimental animal protocols were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee, Tulane University. C57BL/6J mice (3 mo old) were purchased form Jackson Laboratories. Purified brain nonsynaptosomal mitochondria and cardiac mitochondria were isolated as previously described (20, 22). Briefly, tissues were dissected and homogenized in ice-cold mitochondrial isolation buffer (MIB): for brain, consisting of 225 mM sucrose, 75 mM mannitol, 5 mM HEPES, 1 mM EGTA, and 0.5% BSA; and for heart, consisting of 70 mM sucrose, 210 mM mannitol, 5 mM HEPES, 1 mM EGTA, and 0.5% BSA (pH 7.4). After a series of differential centrifugation steps, the crude mitochondrial pellet was reconstituted in 15% Percoll and loaded on top of 24 and 40% Percoll layers and centrifuged at 30,000 g for 8 min. The mitochondrial layer between the 40 and 24% Percoll layers was collected and resuspended in MIB and centrifuged at 16,000 g for 10 min. The resulting pellet was resuspended in 1% BSA (in MIB) and centrifuged at 7,000 g for 10 min. Mitochondrial protein concentration was determined using a BCA kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Mitochondrial respiration measurements.

Mitochondrial respiration was studied using Agilent Seahorse XFe24 analyzer as described previously (20, 22, 25). Mitochondrial suspension was prepared in mitochondrial assay solution (MAS), consisting of 70 mM sucrose, 210 mM mannitol, 2 mM HEPES, 1 mM EGTA, 10 mM potassium phosphate, 5 mM magnesium chloride, and 0.2% BSA (pH 7.4) with (in mM) 10 pyruvate, 2 malate, and 5 ADP. Mitochondria (5 µg in 50 µL) were added to each well of the cell plate and centrifuged at 2,000 g for 20 min of MAS (150 µL, pyruvate-malate-ADP) with or without nNOS and eNOS inhibitors (ARL-17477 and NIO, respectively) were added to the wells, and oxygen consumption rate (OCR) was measured sequentially by injecting 5 µM oligomycin, 5 µM FCCP, and antimycin A (10 µM)-rotenone (2 µM) to measure state III (in the presence of ADP), state IVo (oligomycin), and state IIIu (FCCP) respiration. State III OCR values of the control group were taken as 100, and other OCR values were changed accordingly to reduce the day to day variations between the seahorse experiments. Based on the previous studies, we used each NOS inhibitor at 1 µM concentration (4).

S-nitrosylation of mitochondrial proteins.

Mitochondria were treated with NOS inhibitors and stored at −80°C until analysis. S-nitrosylation of mitochondrial proteins was determined used by the biotin-switch method (Cayman Chemical, Ann Arbor, MI). Briefly, 100 µg of the brain and 25 µg for the cardiac mitochondrial proteins were processed as per the manufacturer’s instructions. Biotin-labeled protein (30 µg; 12.5 µg for heart samples) was used for gel electrophoresis (4–20% gradient polyacrylamide gels, Bio-Rad), immunoblotted with the detection reagent, and S-nitrosylated proteins were visualized using electrochemiluminescence (super signal west Femto maximum sensitivity substrate, Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA).

Immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis.

nNOS and eNOS in brain mitochondria and nNOS in cardiac mitochondria were detected using immunoprecipitation followed by Western blot analysis. eNOS in the cardiac mitochondria was directly detected with the Western blot analysis. Mitochondria were digested in NP-40 cell lysis buffer (Thermo Fischer Scientific, Waltham, MA). Homogenates (200–400 µg for nNOS and 500–750 µg for eNOS in brain mitochondria; 200 µg for nNOS in cardiac mitochondria) were incubated with nNOS (sc-5302, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and eNOS antibodies (610297, BD Biosciences) overnight at 4°C (1:50 dilution). Antigen-antibody complexes pulled down with protein A/G (sc-2003, Santa Cruz Biotechnology) and washed with PBS and dissolved in Laemmli buffer (40 µL). Samples were boiled at 95°C and processed for immunoblotting. For eNOS detection in cardiac mitochondria, 25 µg of mitochondrial homogenate were taken for the immunoblotting.

Statistics.

Statistical difference between the groups was measured using Student’s t-test for the seahorse measurements. Repeated-measures ANOVA was performed to measure the statistical significance for the S-nitrosylation data. Values are reported as means ± SE. P ≤ 0.05 were taken as statistically significant. Parameters that showed significant variation across the groups were log transformed and analyzed with the appropriate parametric test or by nonparametric test.

RESULTS

Effect of NOS inhibitors on isolated brain mitochondria respiration.

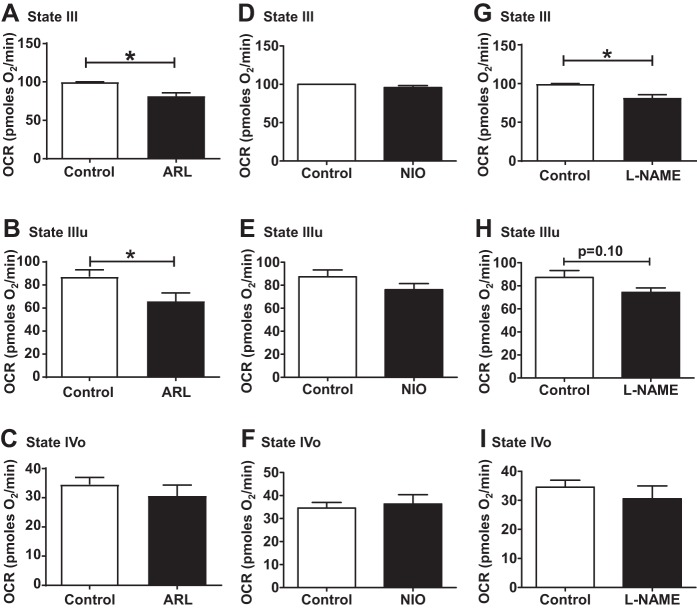

Incubation of brain nonsynaptosomal mitochondria with nNOS-inhibitor ARL significantly decreased the ADP-induced respiration (state III) by 18.5% (Fig. 1A). In contrast, ARL treatment of brain mitochondria significantly decreased FCCP-induced respiration (state IIIu) by 24.5% without altering the state IVo respiration (after oligomycin injection) (Fig. 1, B–C). In contrast, treatment with eNOS-inhibitor NIO did not alter the state III or state IIIu or state IVo respiration of brain mitochondria (Fig. 1, D–F). Like nNOS inhibition, treatment of brain mitochondria with nonspecific NOS-inhibitor l-NAME reduced the basal respiration (Fig. 1G) without changing the state IIIu and state IVo respiration (Fig. 1, H and I).

Fig. 1.

Effect of selective neuronal nitric oxide synthase (NOS) [ARL-17477 (ARL)] and endothelial NOS [N5-(1-iminoethyl)-l-ornithine (NIO)] or nonselective NOS [Nω-nitro-l-arginine methyl ester (l-NAME)] inhibitors on mitochondrial respiration in isolated brain nonsynaptosomal mitochondria. State III, state IVo, and state IIIu for ARL (A–C), NIO (D–F), and l-NAME (G–I) are sown. Isolated brain mitochondria were incubated with 1 µM of ARL or 1 µM of NIO or 1 µM of l-NAME for 30 min. Oxygen consumption rate (OCR, in picomol O2/min) was measured initially (state III) followed by 5 µM oligomycin (state IVo) and 5 µM FCCP injections (state IIIu). Data are expressed as means ± SE; n = 5 mice, including 2 to 4 technical replicates for each mouse. *P < 0.05, significant difference compared with untreated mitochondrial control.

Effect of NOS inhibitors on isolated cardiac mitochondria respiration.

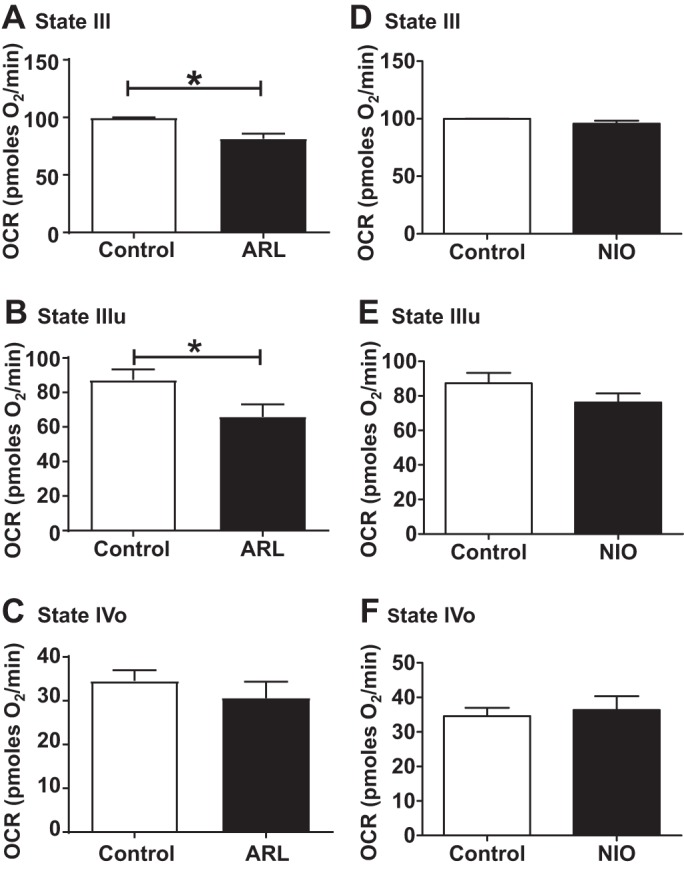

Unlike brain mitochondria, incubating cardiac mitochondria with ARL did not alter the state III respiration, but significantly reduced the state IIIu respiration by 29.2% (Figs. 2, A and B). However, ARL treatment did not alter the state IVo respiration in cardiac mitochondria (Fig. 2C). Similar to that in brain mitochondria, NIO had no effect on the state IIIu respiration as well as state III and state IVo respirations of cardiac mitochondria (Fig. 2, D–F).

Fig. 2.

Effect of selective neuronal nitric oxide synthase (NOS) [ARL-17477 (ARL)] and endothelial NOS [N5-(1-iminoethyl)-l-ornithine (NIO)] inhibitors on mitochondrial respiration in isolated cardiac mitochondria. State III, state IVo, and state IIIu for ARL (A–C) and NIO (D–F) are shown. Isolated cardiac mitochondria were incubated with 1 µM of ARL or 1 µM of NIO for 30 min. Oxygen consumption rate (OCR, in picomol O2/min) was measured initially (state III) followed by 5 µM oligomycin (state IVo) and 5 µM FCCP injections (state IIIu). Data are expressed as means ± SE; n = 12 to 13 mice for ARL and n = 6 to 7 mice for NIO experiments, including 4 to 5 technical replicates for each mouse. *P < 0.05, significant difference compared with untreated mitochondrial control.

Effect of NOS inhibition on S-nitrosylation of proteins.

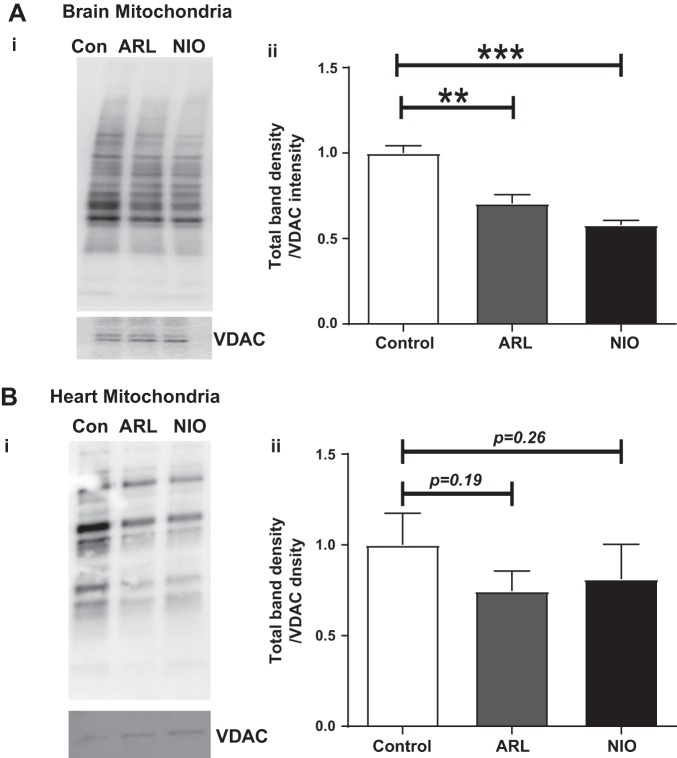

In isolated brain mitochondria, both ARL and NIO significantly decreased the protein S-nitrosylation by 30 and 42%, respectively (Fig. 3B). ARL and NIO treatment of isolated mitochondria from heart showed trend toward decrease in protein S-nitrosylation (25% by ARL with P = 0.19 and 18.8% by NIO with P = 0.26, Fig. 3A).

Fig. 3.

Effect of selective neuronal nitric oxide synthase (NOS) [ARL-17477 (ARL)] and endothelial NOS [N5-(1-iminoethyl)-l-ornithine (NIO)] inhibitors on protein S-nitrosylation in isolated cardiac and brain nonsynaptosomal mitochondria. A,i: representative Western blot for protein S-nitrosylation in brain nonsynaptosomal mitochondria. A,ii: representative bar diagram. B,i: representative Western blot for protein S-nitrosylation in cardiac mitochondria. B,ii: representative bar diagram. Isolated cardiac and brain nonsynaptosomal mitochondria were treated with 1 µM of ARL or 1 µM of NIO for 60 min at 37°C. S-nitrosylated proteins in the mitochondrial lysates were modified by the biotin-switch method and were detected on immunoblots using electrochemiluminescence. Total immunoband intensity was measured with voltage-dependent anion channel (VDAC) protein as the loading control (Con). Data are expressed as means ± SE; n = 3 to 4 mice for brain mitochondria and n = 11 to 12 mice for heart mitochondria. **P < 0.01 and ***P < 0.001, significant difference compared with untreated mitochondrial control.

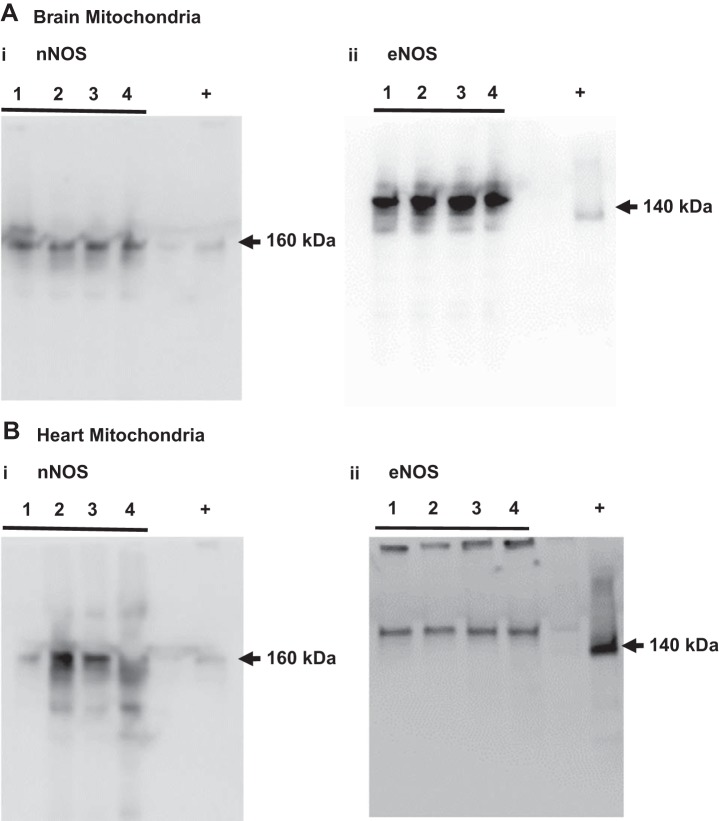

Presence of nNOS and eNOS proteins in isolated cardiac and brain mitochondria.

We detected nNOS protein band above 160 kDa in cardiac and brain mitochondria following the immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis (Fig. 4, A,i and B,i). However, nNOS protein has been reported to be 160 kDa in size. Notably, brain homogenate was used as the positive control and also displayed an immunoband of identical molecular mass, confirming the presence of nNOS in the mitochondria. Interestingly, cardiac mitochondrial homogenates showed eNOS protein bands at molecular mass above 150 kDa (Fig. 4, A,ii). In contrast, brain mitochondria showed 140 kDa-sized eNOS immunoband band following the immunoprecipitation and Western blot analysis, identical in size as the eNOS immunoband in the mouse brain microvessels that served as the positive control (Fig. 4, B,ii). Brain mitochondria also exhibited a strong protein band above 160 kDa and a faint protein band around 130 kDa that were not observed in the eNOS positive control (Fig. 4, A,ii and B,ii).

Fig. 4.

Neuronal nitric oxide synthase (nNOS) and endothelial nitric oxide synthase (eNOS) protein expression in isolated cardiac and brain nonsynaptosomal mitochondria. Representative Western blots of nNOS in brain mitochondria (A,i; immunoprecipitation), eNOS in brain mitochondria (A,ii; immunoprecipitation), nNOS in cardiac mitochondria (B,i; immunoprecipitation), and eNOS in cardiac mitochondria (B,ii); n = 4 mice for each Western blot.

DISCUSSION

Major finding of the present study is that mitochondrial nNOS positively regulates the respiration in isolated mitochondria of both brain and heart, challenging the existing dogma that NO is inhibitory to mitochondrial respiration. First, selective nNOS inhibition reduced basal as well as maximal respiration in the brain mitochondria and reduced maximal respiration in cardiac mitochondria. Second, inhibition of nNOS and eNOS decreased S-nitrosylation of proteins in the brain mitochondria. Finally, immunoreactivities of nNOS and eNOS proteins were observed in cardiac and brain mitochondria. Thus, the current study for the first time presents evidence of functional mtNOS that regulates mitochondrial respiration and protein S-nitrosylation in isolated mitochondria from heart and brain. The significance of the demonstration of differential effects of extramitochondrial NOS and mtNOS on the mitochondria is the potential unique imbalance of their actions in aging that lead to diverse downstream signaling pathways involving sirtuin (13), mTOR (17), and oxidonitrosative stress (21).

Numerous studies have investigated the functional significance of mtNOS. The cardiac mtNOS activity has been shown to be elevated at high altitudes and was proposed to enhance oxygen transport/delivery to tissues (10). nNOS in the heart mitochondria has been shown to afford ischemic preconditioning (11, 12). Cardiac mtNOS was found to promote mPTP opening and lower the membrane potential (Ψm) thereby inhibiting the respiration (2). In addition, mtNOS-derive NO and reactive nitrogen species (RNS) have been shown to inhibit mitochondrial respiration in various cell types by reversibly competing with the oxygen to bind with cytochrome oxidase and inhibit respiratory complexes irreversibly (2).

In this study, inhibition of nNOS but not eNOS decreased the state IIIu respiration in isolated cardiac and brain mitochondria, suggesting that nNOS increases oxygen consumption to achieve enhanced maximal respiration. Interestingly, nonselective NOS inhibitor (NAME) also reduced the mitochondrial respiration-like nNOS inhibitor. Thus, NOS exerts positive effect on the mitochondrial respiration and is essential for maintaining mitochondrial respiration as inhibition of NOS reduced critical aspects of mitochondrial respiration function in isolated mitochondria from two different tissues, brain and heart. These observations challenge the existing dogma that NO exerts inhibitory regulation of the mitochondrial respiration. It may be explained that majority of the studies, we believe, have employed exogenous NO donors at high concentration and are unlikely to simulate the actions of endogenous NO. In fact, recent studies have reported enhancement of mitochondrial respiration by low levels of NO in cardiac mitochondria (5), although basal mitochondrial respiration was unaffected by exogenous NO (8). Furthermore, mtNOS-derived NO localized to mitochondria is likely to elicit distinctly diverse effect on the respiration than exogenous NO (2). Finally, NO-derived from extramitochondrial NOS is likely to have diverse targets than NO derived from mtNOS from within. Further studies are needed to find out whether low NO levels produced in the mitochondria or the diversity of the targets in the microdomain where mtNOS exist underly the paradoxical actions of mtNOS on respiration.

Molecular nature of mtNOS is controversial as majority of the studies identified it as nNOS with a few studies claiming it as eNOS and iNOS (9, 14). In contrast, mtNOS in brain mitochondria is considered to be an nNOS (9, 14). A novel nNOS variant of 144-kDa immunoband was reported in rat brain mitochondria that was found to produce NO sensitive to nNOS inhibition (19). Similarly, a 147-kDa nNOS immunoreactive protein was reported in the isolated mouse brain mitochondria (16). However, Lacza et al. (14) reported the absence of mtNOS in the mouse brain mitochondria as they were unable to detect either the NOS immunoreactivity or the NO production. Consistent with former study, we observed decreased state III and state IIIu respiration in isolated mouse brain mitochondria treated with nNOS inhibitor but not the with the eNOS inhibitor. Thus, mtNOS appears to play the critical role in maintaining maximal respiration in the mitochondria of brain and heart alike.

The controversy surrounding the existence and/or function of mtNOS, we believe, is due to unreliable methods of NO measurement. In the present study, we provided two alternate measures to identify NOS activity by demonstrating the impact of NOS inhibitors on OCR measurements and protein S-nitrosylation. It is noted that NOS is the predominant contributor of protein S-nitrosylation which regulates mitochondrial respiration and other functions in heart and brain (18, 24). Although immunoblotting method detects S-nitrosylation but lacks the sensitivity to detect very low levels of NO generation, it is highly specific to detect NOS activity when used with NOS inhibitors. In this study, both nNOS and eNOS inhibition decreased protein S-nitrosylation in the isolated brain mitochondria, suggesting existence of autonomous mtNOS-dependent S-nitrosylation in the brain mitochondria. In contrast, S-nitrosylation in cardiac mitochondria was not significantly reduced by NOS inhibition, although there was a trend. This may be due to low levels of NO production which is below the threshold of detection. As per our knowledge, there has only been one previous study that reported the decreased protein S-nitrosylation with l-NAME in the liver mitochondria (14), but the present study is the first to show the regulation of protein S-nitrosylation by mtNOS in the isolated brain mitochondria. Interestingly, S-nitrosylation by nNOS/eNOS in brain mitochondria is not correlated with the promotion of respiration in brain mitochondria, as nNOS inhibition but not eNOS-inhibition inhibited mitochondrial respiration. In contrast, although neither nNOS nor eNOS induced significant S-nitrosylation in cardiac mitochondria, only nNOS promoted increased respiration. Taken together, these findings imply that S-nitrosylation is not essential for modulating mitochondrial respiration.

Limitations.

The isolated mitochondria were prepared from the homogenates of heart and mitochondria consistent with the practice of similar studies. Although the mitochondria originated from multitude of cells, the predominant sources are believed to be cardiomyocytes and neurons for heart and brain, respectively. Furthermore, the selectivity of the NOS inhibitors is often debated, but the concentration of the agents used in the present study ensure selectivity consistent with previous literature.

We conclude that mitochondrial nNOS is essential to maintain maximal respiration in cardiac and brain mitochondria which affords the mitochondria the ability to achieve enhanced maximal respiration to meet increased energy demand placed on the cells. Furthermore, mitochondrial nNOS-mediated effects on respiration in heart mitochondria were associated with protein S-nitrosylation, and mitochondrial eNOS does not regulate respiration despite mediating protein S-nitrosylation. Further studies are needed to identify the specific mechanisms involved in the mtNOS-mediated regulation of maximal respiration in the isolated mitochondria.

GRANTS

This research project was supported by National Institutes of Health Grants NS-094834 (to P. V. G. Katakam), R01-AG-047296 (to R. Mostany), and DK-107694 (to R. Satou). In addition, the study was supported by American Heart Association National Center Scientist Development Grant 14SDG20490359 (to P. V. G. Katakam), Greater Southeast Affiliate Predoctoral Fellowship Award 16PRE27790122 (to V. N. Sure), Predoctoral Fellowship Award 20PRE35211153 (to W. R. Evans), and Louisiana Board of Regents Grants RCS, LEQSF(2016-19)-RD-A-24 (to R. Mostany).

DISCLAIMERS

The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

S.S.V.P.S., J.A.S., W.R.E., and P.V.G.K. conceived and designed research; S.S.V.P.S., J.A.S., W.R.E., M.H.D., A.L.A., and V.N.S. performed experiments; S.S.V.P.S., J.A.S., W.R.E., M.H.D., A.L.A., V.N.S., and P.V.G.K. analyzed data; S.S.V.P.S., J.A.S., W.R.E., M.H.D., A.L.A., V.N.S., and P.V.G.K. interpreted results of experiments; S.S.V.P.S. and J.A.S. prepared figures; S.S.V.P.S. and J.A.S. drafted manuscript; S.S.V.P.S., J.A.S., W.R.E., M.H.D., A.L.A., V.N.S., R.S., R.M., and P.V.G.K. edited and revised manuscript; S.S.V.P.S., J.A.S., W.R.E., M.H.D., A.L.A., V.N.S., R.S., R.M., and P.V.G.K. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Sufen Zheng for technical help for the studies.

REFERENCES

- 1.Beltrán B, Quintero M, García-Zaragozá E, O’Connor E, Esplugues JV, Moncada S. Inhibition of mitochondrial respiration by endogenous nitric oxide: a critical step in Fas signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA 99: 8892–8897, 2002. doi: 10.1073/pnas.092259799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Brown GC, Borutaite V. Nitric oxide and mitochondrial respiration in the heart. Cardiovasc Res 75: 283–290, 2007. doi: 10.1016/j.cardiores.2007.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen ZQ, Mou RT, Feng DX, Wang Z, Chen G. The role of nitric oxide in stroke. Med Gas Res 7: 194–203, 2017. doi: 10.4103/2045-9912.215750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dedkova EN, Blatter LA. Characteristics and function of cardiac mitochondrial nitric oxide synthase. J Physiol 587: 851–872, 2009. doi: 10.1113/jphysiol.2008.165423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dynnik VV, Grishina EV, Fedotcheva NI. The mitochondrial NO-synthase/guanylate cyclase/protein kinase G signaling system underpins the dual effects of nitric oxide on mitochondrial respiration and opening of the permeability transition pore. FEBS J. 2019 Oct 11. [Epub ahead of print.] doi: 10.1111/febs.15090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Farah C, Michel LY, Balligand JL. Nitric oxide signalling in cardiovascular health and disease. Nat Rev Cardiol 15: 292–316, 2018. doi: 10.1038/nrcardio.2017.224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Forstermann U, Sessa WC. Nitric oxide synthases: regulation and function. Eur Heart J 33: 829–837, 2012. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehr304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.French S, Giulivi C, Balaban RS. Nitric oxide synthase in porcine heart mitochondria: evidence for low physiological activity. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 280: H2863–H2867, 2001. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.2001.280.6.H2863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ghafourifar P, Cadenas E. Mitochondrial nitric oxide synthase. Trends Pharmacol Sci 26: 190–195, 2005. doi: 10.1016/j.tips.2005.02.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gonzales GF, Chung FA, Miranda S, Valdez LB, Zaobornyj T, Bustamante J, Boveris A. Heart mitochondrial nitric oxide synthase is upregulated in male rats exposed to high altitude (4,340 m). Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol 288: H2568–H2573, 2005. doi: 10.1152/ajpheart.00812.2004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hu L, Wang J, Zhu H, Wu X, Zhou L, Song Y, Zhu S, Hao M, Liu C, Fan Y, Wang Y, Li Q. Ischemic postconditioning protects the heart against ischemia-reperfusion injury via neuronal nitric oxide synthase in the sarcoplasmic reticulum and mitochondria. Cell Death Dis 7: e2222, 2016. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kirca M, Kleinbongard P, Soetkamp D, Heger J, Csonka C, Ferdinandy P, Schulz R. Interaction between connexin 43 and nitric oxide synthase in mice heart mitochondria. J Cell Mol Med 19: 815–825, 2015. doi: 10.1111/jcmm.12499. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Kiss T, Balasubramanian P, Valcarcel-Ares MN, Tarantini S, Yabluchanskiy A, Csipo T, Lipecz A, Reglodi D, Zhang XA, Bari F, Farkas E, Csiszar A, Ungvari Z. Nicotinamide mononucleotide (NMN) treatment attenuates oxidative stress and rescues angiogenic capacity in aged cerebromicrovascular endothelial cells: a potential mechanism for the prevention of vascular cognitive impairment. Geroscience 41: 619–630, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s11357-019-00074-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lacza Z, Pankotai E, Busija DW. Mitochondrial nitric oxide synthase: current concepts and controversies. Front Biosci 14: 4436–4443, 2009. doi: 10.2741/3539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Leite AC, Oliveira HC, Utino FL, Garcia R, Alberici LC, Fernandes MP, Castilho RF, Vercesi AE. Mitochondria generated nitric oxide protects against permeability transition via formation of membrane protein S-nitrosothiols. Biochim Biophys Acta 1797: 1210–1216, 2010. doi: 10.1016/j.bbabio.2010.01.034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lores-Arnaiz S, D’Amico G, Czerniczyniec A, Bustamante J, Boveris A. Brain mitochondrial nitric oxide synthase: in vitro and in vivo inhibition by chlorpromazine. Arch Biochem Biophys 430: 170–177, 2004. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2004.07.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Nacarelli T, Azar A, Altinok O, Orynbayeva Z, Sell C. Rapamycin increases oxidative metabolism and enhances metabolic flexibility in human cardiac fibroblasts. Geroscience 40: 243–256, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s11357-018-0030-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakamura T, Prikhodko OA, Pirie E, Nagar S, Akhtar MW, Oh CK, McKercher SR, Ambasudhan R, Okamoto S, Lipton SA. Aberrant protein S-nitrosylation contributes to the pathophysiology of neurodegenerative diseases. Neurobiol Dis 84: 99–108, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2015.03.017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Riobo NA, Melani M, Sanjuan N, Fiszman ML, Gravielle MC, Carreras MC, Cadenas E, Poderoso JJ. The modulation of mitochondrial nitric-oxide synthase activity in rat brain development. J Biol Chem 277: 42447–42455, 2002. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M204580200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sakamuri SSVP, Sperling JA, Sure VN, Dholakia MH, Peterson NR, Rutkai I, Mahalingam PS, Satou R, Katakam PVG. Measurement of respiratory function in isolated cardiac mitochondria using Seahorse XFe24 Analyzer: applications for aging research. Geroscience 40: 347–356, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s11357-018-0021-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Şakul A, Arı N, Sotnikova R, Ozansoy G, Karasu Ç. A pyridoindole antioxidant SMe1EC2 regulates contractility, relaxation ability, cation channel activity, and protein-carbonyl modifications in the aorta of young and old rats with or without diabetes mellitus. Geroscience 40: 377–392, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s11357-018-0034-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sperling JA, Sakamuri SSVP, Albuck AL, Sure VN, Evans WR, Peterson NR, Rutkai I, Mostany R, Satou R, Katakam PVG. Measuring Respiration in Isolated Murine Brain Mitochondria: Implications for Mechanistic Stroke Studies. Neuromolecular Med 21: 493–504, 2019. doi: 10.1007/s12017-019-08552-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Strijdom H, Chamane N, Lochner A. Nitric oxide in the cardiovascular system: a simple molecule with complex actions. Cardiovasc J Afr 20: 303–310, 2009. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun J, Murphy E. Protein S-nitrosylation and cardioprotection. Circ Res 106: 285–296, 2010. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.109.209452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sure VN, Sakamuri SSVP, Sperling JA, Evans WR, Merdzo I, Mostany R, Murfee WL, Busija DW, Katakam PVG. A novel high-throughput assay for respiration in isolated brain microvessels reveals impaired mitochondrial function in the aged mice. Geroscience 40: 365–375, 2018. doi: 10.1007/s11357-018-0037-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tabatabaei SN, Girouard H. Nitric oxide and cerebrovascular regulation. Vitam Horm 96: 347–385, 2014. doi: 10.1016/B978-0-12-800254-4.00014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]