Abstract

During the newborn period, intestinal commensal bacteria influence pulmonary mucosal immunology via the gut-lung axis. Epidemiological studies have linked perinatal antibiotic exposure in human newborns to an increased risk for bronchopulmonary dysplasia, but whether this effect is mediated by the gut-lung axis is unknown. To explore antibiotic disruption of the newborn gut-lung axis, we studied how perinatal maternal antibiotic exposure influenced lung injury in a hyperoxia-based mouse model of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. We report that disruption of intestinal commensal colonization during the perinatal period promotes a more severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia phenotype characterized by increased mortality and pulmonary fibrosis. Mechanistically, metagenomic shifts were associated with decreased IL-22 expression in bronchoalveolar lavage and were independent of hyperoxia-induced inflammasome activation. Collectively, these results demonstrate a previously unrecognized influence of the gut-lung axis during the development of neonatal lung injury, which could be leveraged to ameliorate the most severe and persistent pulmonary complication of preterm birth.

Keywords: gut-lung axis, interleukin-22, microbiome, mucosal immunology, pulmonary fibrosis

INTRODUCTION

Commensal microorganism ecology develops rapidly during the newborn period (3). Emerging evidence suggests the microbial colonization of the intestine influences immune system development and, by extension, alters inflammatory processes (50). A critical window exists during the early neonatal period where altered maturation of the microbiota can disrupt immune development with profound consequences that may extend into adulthood (4, 22). Moreover, gut-immune-lung crosstalk is critical to lung disease (6, 34, 38, 49), and the intestinal microbiome affects immune response at distal sites (12, 14, 28, 41, 48, 53). This interplay has been termed the ‘gut-lung axis’ (40), and it may provide a crucial influence on respiratory function in early life.

Antibiotic administration has an intuitive and profound impact on the microbiome (7). Unfortunately, preterm infants are extensively exposed to antibiotics (23, 29). Although the effects of antibiotics are thought to be temporary in adults (18), perinatal antibiotic exposure may have long-term effects on organ development that remain largely unexplored (4, 22).

Intriguingly, antibiotic exposure is linked to increased risk of developing bronchopulmonary dysplasia (BPD) (9, 46), which remains the most serious and prevalent pulmonary complication of preterm birth (33, 51). With growing evidence for the importance of the gut-lung axis in BPD, one potential explanation for this association is that microbial dysbiosis in the neonatal period ultimately programs lung inflammation to augment BPD pathogenesis.

To explore antibiotic disruption of the neonatal gut-lung axis, we studied how maternal antibiotic exposure (MAE) influenced lung injury in offspring in a hyperoxia-based mouse model of BPD. Here, we show that disruption of intestinal commensal communities by maternal antibiotic exposure promoted a more severe phenotype of BPD characterized by increased pulmonary fibrosis. Changes in lung architecture secondary to alterations in neonatal microbial ecology were independent of oxygen exposure-related inflammasome activation and associated with decreased IL-22 in bronchoalveolar lavage. This work demonstrates a novel role for the gut-lung axis in the pathogenesis of BPD.

METHODS

Animals.

Specific pathogen-free C57BL/6J breeder mice were obtained from The Jackson Laboratory (RRID:IMSR_JAX:000664, Bar Harbor, ME) and housed in pathogen-free animal housing within the pulmonary function facility at the University of Tennessee Health Science Center (UTHSC; Memphis, TN). The Animal Care and Use Committee approved all mouse protocols, and experiments were conducted according to NIH guidelines. To clarify the effects of the microbiome on lung injury, we used a standardized neonatal hyperoxia exposure-based mouse model of BPD (45), proceeded by alteration of the maternal microbiome with antibiotics, to create a two-exposure model of hyperoxia preceded by disruption of neonatal commensal colonization. MAE was performed by administering penicillin VK (500 mg/L) via the maternal drinking water (utilizing average rates of consumption and bodyweight, this is approximately 0.08–0.1 mg·g−1·day−1) (13, 17). The dose was further clarified using a series of pilot experiments with doses ranging from 5–500 mg/mL. Previous literature indicates a limited transfer of antibiotics from dam to pup at these concentrations, with disruption of neonatal colonization being the primary mechanism for alterations in the neonatal microbiome of resulting offspring (13, 17, 43). Mice were housed in ventilated cages with a filtered air supply and 12-h light-dark cycle. After a period of cohousing to homogenize maternal mouse microbiomes, we time-mated the mice to produce the maximum number of simultaneous birth cohorts. Pregnant dams were randomized on gestational day 15 to either standard care or antibiotic exposure. On the day of birth, pups from two consecutively born litters with the same perinatal exposure were pooled and the pups were distributed evenly between the two dams. Litter sizes for all experiments were adjusted to 5–8 pups per treatment group to minimize nutritional effects on lung development. One pooled litter was assigned to hyperoxia [fraction of inspired oxygen () 0.60 or 0.8]) and the other to air ( 0.21). Pups were exposed continuously for 14 days in a Plexiglass chamber (Cleatech, Santa Ana, CA) starting on the day after birth. Oxygen concentrations were maintained using a ProOx monitor (Biospherix, Rockfield, NY). Dams were rotated daily between the two pooled litters to limit the complications of hyperoxia. For neonatal lungs not used for histology, we calculated the lung-to-body weight ratio and monitored growth of the pups throughout the experiment. To further clarify the critical exposure period, we performed a crossover experiment. Starting with two MAE litters and two nonexposed litters per treatment arm, we cross-fostered the pups at delivery: pups that were prenatally exposed (preMAE) were fostered to dams with an intact microbiome, and unexposed pups were fostered to exposed dams so that the pups were postnatally exposed (postMAE). Neonatal mice were examined for sex at the end of each experiment and tail snips saved for genetic confirmation.

Lung morphometric analysis.

To quantify the effects of lung injury, we performed morphometric analysis using histologic sections of whole lung. After exposure to hyperoxia or air, pups were weighed and euthanized for tissue harvest. The lungs of each animal were gravity inflated with zinc formalin. Three random sections from the lungs of each animal were stained with hematoxylin and eosin with the assistance of Drs. Balazs and Seagroves at the UTHSC Research Histology Core. Lung sections from each experiment were digitized under ×20 magnification and analyzed independently by two operators blinded to the group assignments. Images were captured using an EVOS FL Auto microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL). Alveolarization was quantified using the mean linear intercept (Lm), weighted averages of the alveolar area (D1, D2), and mean septal thickness. D1 and D2 were calculated using a Python script, which was the kind gift of James Carson (32) (available at: https://github.com/jamescarson3/computeD2). Manual calculations of the Lm were verified against a semiautomated method using FIJI (42). To quantify pulmonary fibrosis, Masson trichrome staining of slides from three pups/group was performed by the UTHSC Research Histology Core. Five representative images were obtained at ×20 from each slide and analyzed by two operators blinded to the group assignments using a pathology score validated to quantify hyperoxia exposure-related lung injury in the mouse (31) and a pseudocolorimetric image analysis technique to quantify the amount of green-stained collagen fibers in Masson trichrome stained tissue (11).

Immunohistochemistry.

To further explore compositional changes in the interalveolar septa, representative slides were cut from paraffin-embedded samples. Three slides per group were deparaffinized and rehydrated with graduated concentrations of ethanol, underwent antigen retrieval with 10 μM Sodium Citrate Buffer with 20% Tween, were blocked in blocking buffer (1% horse serum BSA) for 30 min, and were incubated overnight with primary antibodies (described below) at 2–8°C in incubation buffer (1% BSA, 1% normal donkey serum, 0.3% Triton X-100, and 0.01% sodium azide in PBS) prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The next day they were washed again in PBS, fenestrated, blocked with Mouse BD Fc Block (Clone 2.4G2, cat. no. 553142, RRID: AB_394657, BD Biosciences), and then counterstained with ProLong Diamond Anti-Fade Mounting Media with DAPI (4′,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole; cat. no. P36962, RRID:AB_2307445, Thermo Fisher Scientific). Images were then captured using an Eclipse Ti2-E inverted microscope system (Nikon, Tokyo, Japan). Primary antibodies included the following: APC rat anti-mouse CD45 (Clone 30-F11, lot no. 4271830, cat. no. 561018, RRID:AB_10584326, BD Biosciences) and mouse monoclonal anti-α smooth muscle actin (αSMA) Cy3 antibody (Clone 1A4, lot no. 059M4797V, cat. no. C6198, RRID: AB_476856, Sigma-Aldrich). Representative images were then captured at ×20 magnification. We also prepared additional slides using the myeloperoxidase polyclonal antibody (cat. no. PA5-16672, RRID:AB_11006367, Thermo Fisher Scientific).

Vascular density.

In addition to quantifying capillaries with a diameter less than 50 μm stained with αSMA, to further quantify vascular density, we used a polyclonal antibody of anti-von Willebrand Factor (vWF) (cat. no. ab6994, RRID:AB_305689, Abcam). Five representative images at ×20 were captured on an EVOS FL Auto microscope (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Rockford, IL) using systematic random sampling. To quantify vascular density, we counted the number of vWF-positive vessels (both venules and capillaries) with a diameter less than 50 μm per ×20 high-power field using an established method (10).

Inflammasome activity.

We assessed inflammasome activity using a caspase-1 bioluminescent assay kit prepared according to the manufacturer’s instructions from a whole lung homogenate of three mice per group. Samples were initially snap-frozen and stored at −80°C at the termination of each experiment (Caspase-Glo 1 Inflammasome Assay, cat. no. G9951, Promega, Madison, WI).

Microbiota depletion and 16S microbial community analysis.

To study the influence of commensal ecological diversity, we depleted the intestinal microbiota by exposing pregnant dams to penicillin (500 mg/L) via the drinking water ad libitum starting on gestational day 15. Antibiotic administration to the dam was continued throughout the exposure period to hyperoxia or air. The entire colonic contents were collected from the resulting offspring at the termination of each experiment (postnatal day 15, P15) and snap frozen in liquid nitrogen before being stored at −80°C. Intestinal contents were resuspended in 500 μL of TNES buffer containing 200 units of lyticase and 100 μL of 0.1/0.5 (50/50 Vol.) virconia beads. Samples were incubated for 20 min at 37°C before 2 × 1 min of ultra-high-speed bead beating. After mechanical disruption, 20 μg of proteinase K were added to all samples. Samples were incubated overnight at 55°C with agitation. The following day, total DNA was extracted with the chloroform isoamyl alcohol method. Total DNA concentration per mg stool was determined by qRT-PCR. DNA samples were sent to the Argonne National Laboratory (Lemont, IL) for 16S metagenomic barcoding using the NextGen Illumina MiSeq platform. Blank samples passed through the entire collection, extraction, and amplification process did not produce any DNA amplification. Microbial genomic DNA was isolated, and the variable 4 region of the 16S rRNA gene was amplified using unique barcoded primers. Sequence data were processed and analyzed using QIIME 1.9.1. The data were then imported into Calypso 8 for further analysis and visualization. Samples were normalized using the Hellinger Transformation (square root of total sum normalization). The Shannon Diversity Index was used to quantify alpha diversity (intersample). Structured principal coordinates analysis (PCoA) of Bray–Curtis dissimilarity matrices, nonmetric multidimensional scaling, and unstructured redundancy analysis (RDA) were used to analyze beta diversity. Permutational multivariate analysis of variance (PERMANOVA) with 999 permutations was used to assess statistical significance of the PCoA. To quantify relative abundance of taxa between groups, we utilized either the Kruskal–Wallis test or one-way ANOVA adjusted for false discovery. Network analysis was performed using Spearman’s correlations with positive false-discovery-rate adjusted P values < 0.05 displayed as an edge.

Characterization of bronchoalveolar lavage.

To quantify alterations in lung cytokine levels, we isolated bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) fluid with 0.3 mL of PBS and 0.5% BSA. BAL was used in the Milliplex Map Mouse Cytokine/Chemokine Magnetic Bead assay (cat. no. MCYTOMAG-70K-PMX, Millipore Sigma, Billerica, MA) for TNFα, IL-1β, IL-6, IL-17A, and IL-22. Samples were incubated overnight at 4°C and analyzed using a Luminex 200 SD System (EMD Millipore, Burlington, MA).

Statistical analysis.

For each analysis, the data presented are from two to three pooled experiments with five to eight pups per group in each experiment. Data are presented as means ± SE. Where indicated, data are further expressed as fold changes relative to air controls or as median ± interquartile range. The effects of microbiome depletion and hyperoxia exposure were tested by two-way ANOVA (Prism v8.2, GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). For nonparametric data, the Friedman rank sum test was run in R using the “stats” package (46a). Variables were considered significant with a false-discovery adjusted P < 0.05.

RESULTS

Microbial colonization by commensal bacteria promotes resistance to lung injury in neonatal mice.

Maternal and frequent direct postnatal antibiotic exposure have been linked to alterations of the intestinal microbiome in human newborns and an increased risk later in life for immune-mediated pulmonary conditions such as asthma and pneumonia (20). This led us to hypothesize that perinatal exposure to commensal bacteria would promote resistance to lung injury in preterm newborns. To test this hypothesis, we exposed pregnant mouse dams that had initially been cohoused to homogenize their microbial colonization to the most commonly used perinatal antibiotic, penicillin (23, 29), starting on the tenth day of gestation. We then studied the colonic microbiota of the pups and changes in their lung architecture at 15 days of life (Fig. 1A).

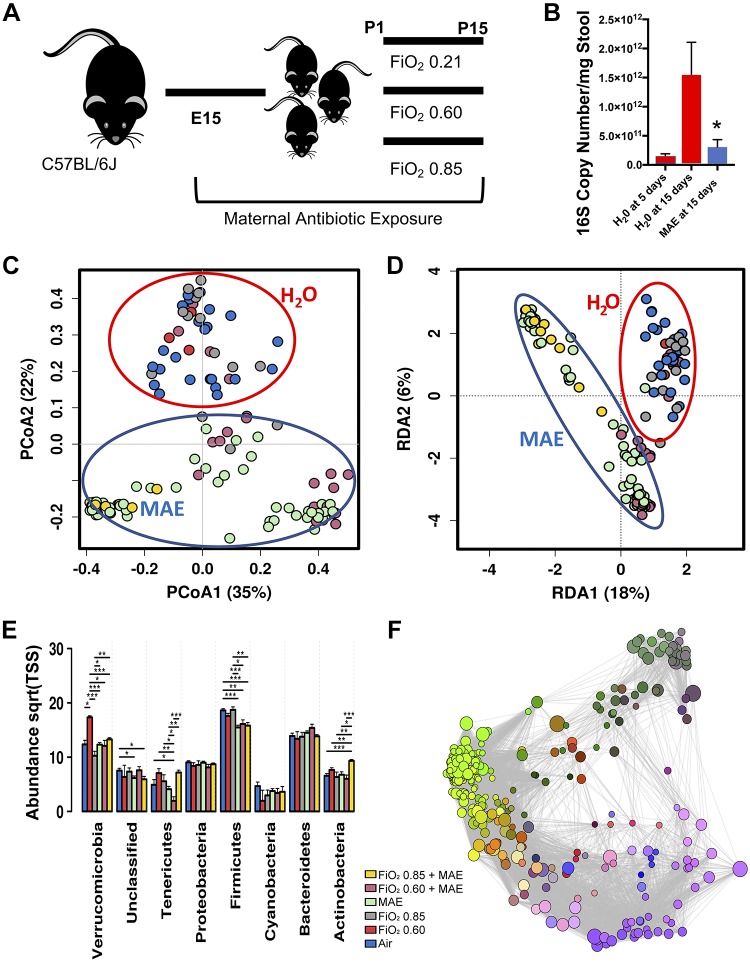

Fig. 1.

Maternal antibiotic exposure induces a characteristic commensal disruption of the neonatal gut microbiome at 15 days of life. A: experimental schema. C57Bl/6J mice were cohoused to normalize the microbiome and then time-mated to produce multiple simultaneous litters exposed to either maternal antibiotic exposure (MAE) or purified water (controls). After birth, neonatal mice were exposed to either normoxia (air) or hyperoxia for 14 days. Neonatal mice were humanely euthanized for stool and tissue collection at 15 days of life. E15, embryonic day 15; P15, postnatal day 15. B: as quantified by qRT-PCR, MAE reduced the absolute abundance of the bacterial 16S rRNA gene in the neonatal colon at 15 days to a level similar to a specific pathogen-free 5-day-old pup (one-way ANOVA, P = 0.0374). C: structured principal coordinates analysis [PCoA, permutational multivariate ANOVA (PERMANOVA) with 999 permutations of Bray–Curtis dissimilarity, R2 = 0.302, P = 0.00033]. D: unstructured redundancy analysis (RDA, variance 87.29, f = 8.46, P = 0.001). C and D demonstrate that the composition of the neonatal colonic microbiome at 15 days of life differs by exposure to MAE and not hyperoxia. Centroids added for emphasis. E: differences in relative abundance at the phylum level. Sqrt(TSS), square root total sum normalization (Hellinger Transformation). F: Spearman network analysis. Positive correlations with false discovery rate-adjusted P values < 0.05 are displayed as an edge, and relative size represents significance of the edge to the surrounding network. n = 5–8 pups/group in 3 independent experiments; data points represent individual animals. One-way ANOVA, Bonferroni, *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001. , fraction of inspired oxygen; P0, day of birth.

Under undisrupted development, the intestinal commensal bacterial load of newborn pups expands markedly after birth. By 15 days of life, MAE disrupted commensal colonization, as quantified by the absolute number of bacteria to levels observed in 5-day-old unexposed mice (one-way ANOVA, P = 0.0374; Fig. 1B) and produced marked shifts in the bacterial colonization pattern (Fig. 1 and Supplemental Fig. S1; all Supplemental Material is available at https://doi.org/10.6084/m9.figshare.9891209) and the predicted metagenome (Supplemental Fig. S2 and Supplemental Table S1). MAE also altered the median alpha diversity (Shannon Diversity Index, one-way ANOVA, f = 4.1, P = 0.0019; Supplemental Fig. S1D) and led to significant shifts in the beta diversity (PCoA PERMANOVA with 999 permutations of Bray–Curtis dissimilarity, R2 = 0.302, P = 0.00033; Fig. 1C and unstructured RDA, variance 87.29, f = 8.46, P = 0.001; Fig. 1D). At the phylum level, the most prominent shift related to MAE was in Firmicutes, with combinatory effects of hyperoxia exposure and MAE resulting in shifts in Verrucomicrobia, Tenericutes, and Actinobacteria (Fig. 1E). Overall, the most significant changes were reduced abundance of the order Erysipelotrichales and the genus Lactobacillus, leading to an expansion in the family Peptostreptococcacea and genus Anaerofustis (Supplemental Fig. S3A). MAE also altered the predicted metagenome (Supplemental Table S1). Network analysis further supports the influence of MAE on multiple bacteria genera (Fig. 1F). Alterations in the microbial colonization pattern are enhanced by hyperoxia exposure (Fig. 1), but, importantly, colonization of the neonatal gut was not significantly altered by exposure to hyperoxia alone (Supplemental Fig. S4).

To explore how commensal colonization influenced neonatal hyperoxia-based lung injury, we used morphometry of lung histology to compare changes in lung architecture between neonatal pups born after MAE to age-matched, unexposed controls (Fig. 2). At baseline, the Lm and septal thickness of MAE-negative controls is consistent with the established literature at 0.21, 0.60, and 0.85 (45). In general, MAE alone increased the mean septal thickness and the Lm but did not significantly alter alveolar heterogeneity (D1 and D2, Fig. 2B). However, in combination with hyperoxia exposure, MAE produced characteristic changes that increased the septal thickness and the Lm but produced only an interactive effect on alveolar area heterogeneity (Fig. 2B). No effect of sex was appreciated on the Lm, septal thickness, or alveolar heterogeneity (three-way ANOVAs, NS for sex). Taken together, these results suggest that MAE disrupts neonatal intestinal colonization, potentiates alveolar simplification, and increases septal thickness after hyperoxia exposure.

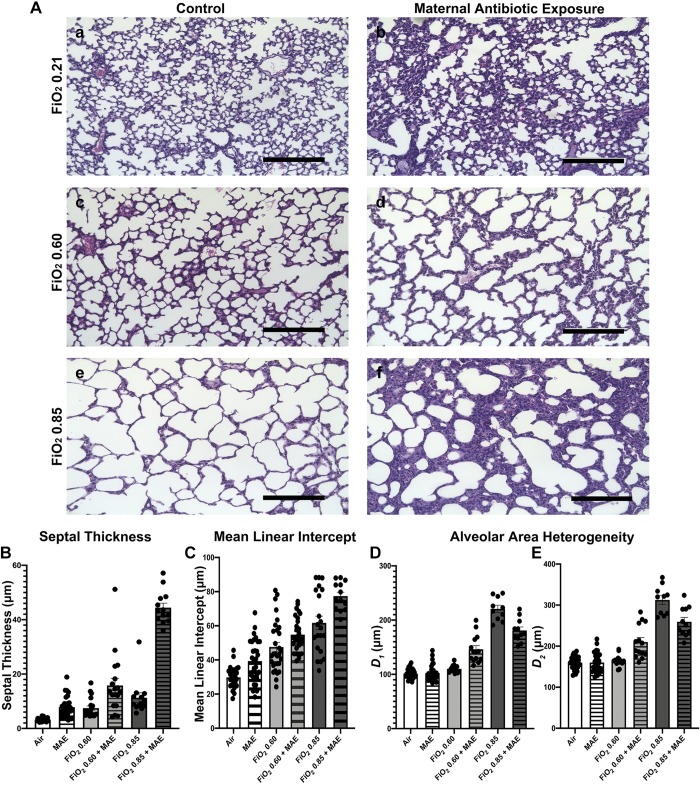

Fig. 2.

Commensal disruption produces a more severe phenotype of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. A: representative micrographs of hematoxylin and eosin-stained lung sections that were gravity inflation-fixed from 15-day-old neonatal mice exposed to either normoxia (air) (Aa), maternal antibiotic exposure (MAE) and normoxia (Ab), fraction of inspired oxygen () 0.60 (Ac), MAE and 0.60 (Ad), 0.85 (Ae), or MAE and 0.85 (Af). Scale bars represent 200 μm. B: septal thickness, two-way ANOVA interaction, MAE and hyperoxia, P < 0.001. C: mean linear intercept, two-way ANOVA interaction not significant (NS), MAE, P = 0.0004; hyperoxia, P < 0.001. D and E: airway heterogeneity (weighted means of airway diameter, D1 and D2) demonstrates only an interactive effect of MAE (two-way ANOVA interaction, P < 0.0001; MAE NS, hyperoxia, P < 0.0001); n = 5–8 pups/group in 3 independent experiments; data points represent individual animals and error bars display mean ± SE.

Increasing oxygen concentration potentiates maternal antibiotic exposure-induced alterations in lung architecture.

To explore how dose-dependent changes in oxygen exposure altered lung architecture after MAE, we exposed newborn pups to two different concentrations of hyperoxia: 0.60 and 0.85. As the concentration of oxygen increased, a combinatory increase in the Lm and septal thickness but not alveolar area heterogeneity was noted (Fig. 2B). We did not observe an effect of sex as a biological variable. Overall, these results suggest that increasing oxygen exposure potentiates enlargement of the interalveolar septa driven by MAE. Increased septal thickness contributes to clinical morbidity by increasing the diffusion distance, suggesting that in combination with MAE hyperoxia increased the severity of BPD.

Lung injury following maternal antibiotic exposure is characterized by increased pulmonary fibrosis.

To determine whether increased septal thickness following MAE primarily represented pulmonary fibrosis, we assessed collagen deposition using a pathology score (31) and an image analysis technique (11). In conjunction with what has been previously described (16), exposure to hyperoxia increased pulmonary fibrosis. MAE, however, potentiated the formation of fibrosis, as quantified by an increase in the median pathology score, both in combination with normoxia and to a greater extent in combination with hyperoxia (Friedman rank sum test, P < 0.0001; Fig. 3A). We supported these findings by quantifying collagen deposition in a subset of samples using image analysis and noted that MAE led to a higher relative density of collagen fibers (two-way ANOVA interaction, NS; MAE, P < 0.0001; hyperoxia, NS; Supplemental Fig. S5A). Together, these data provide evidence that disruption of commensal colonization produces altered lung architecture characterized by increased pulmonary fibrosis.

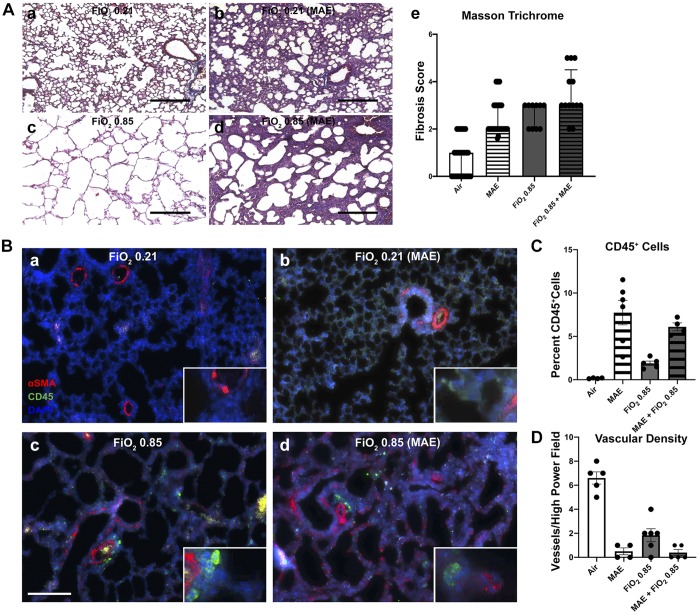

Fig. 3.

Commensal disruption increases fibrosis and immune cell recruitment and decreases vascular density. a–d: for each group of representative micrographs: normoxia alone (a), maternal antibiotic exposure (MAE) alone (b), hyperoxia exposure at fraction of inspired oxygen () 0.85 alone (c), and the combined exposure of MAE and hyperoxia (d). A: Masson trichrome staining with data presented as median ± interquartile range of a pathology score (Ae) (Friedman rank sum test, P < 0.0001). Black scale bars represent 200 μm. Data points represent individual animals; n = 3–5 pups/group in 3 independent experiments. B: representative immunohistochemistry for CD45 (Cy5, pseudocolored green channel) and α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA, red channel). C: quantification of the percentage of CD45-positive cells (two-way ANOVA interaction and hyperoxia exposure not significant; MAE, P < 0.001). D: quantification of the number of αSMA-positive vessels <50 μm in diameter per ×20 microscopic field (two-way ANOVA interaction, P = 0.001; hyperoxia exposure and MAE, P < 0.001). White scale bar represents 100 μm. n = 3–5 pups/group; data points represent individual animals, and error bars display mean ± SE.

Maternal antibiotic exposure increases CD45-postive cells and granulocytes.

MAE increased the number of CD45-positive cells in the interalveolar septa (two-way ANOVA interaction and hyperoxia, NS; MAE, P < 0.001; Fig. 3B). In the combined exposure, αSMA-positive cells can also be observed, further providing additional evidence for increased early fibrotic changes produced by the combined exposure. Similarly, MAE also increased granulocytic infiltration in combination with both room air and hyperoxia, as quantified by the percentage of myeloperoxidase positive nuclei (two-way ANOVA interaction, NS; MAE, P = 0.0002, hyperoxia exposure, NS; Supplemental Fig. S6A). Together, these results show potentiation of immune infiltration after MAE, suggesting that in addition to altering lung architecture, immune-mediated processes may play a role in lung injury after commensal disruption.

Maternal antibiotic exposure potentiates hyperoxia-induced pulmonary vascular remodeling.

MAE significantly reduced the density of pulmonary capillaries (αSMA-positive muscularized vessels with a diameter less than 50 μm per high-power field; two-way ANOVA interaction, P = 0.00; MAE and hyperoxia, P < 0.001; Fig. 3, B and C; Supplemental Fig. S6B). Additionally, MAE significantly decreased the density of all vessels as quantified by vWF-positive vessels with a diameter <50 μm per high-power field (two-way ANOVA interaction and MAE, P < 0.0001; hyperoxia, P = 0.0002; Supplemental Fig. S6C). This finding demonstrates that changes in lung architecture after commensal community disruption dramatically reduces pulmonary vasculature crucial for functional gas exchange in our model. Reduced vascular density and subsequent pulmonary hypertension are important causes of increased mortality in BPD (1) and may have significant implications for the clinical care of newborns extensively exposed to antibiotics.

Maternal antibiotic exposure leads to increased mortality.

We monitored survival until the predetermined end point of the experiments. At all timepoints, MAE produced an imprecise trend toward increased mortality (Fig. 4A). However, in combination with 0.85, MAE significantly increased mortality over hyperoxia alone (log-rank test, P = 0.002). Hyperoxia alone did not produce a significant increase in mortality. Two distinct phases of mortality can also be appreciated. While earlier mortality during the first several days is less clearly linked to the combined exposure and may represent mortality from hyperoxia exposure, later mortality clearly increased with the combined exposure. These results suggest that commensal disruption potentiates mortality during the development of hyperoxia exposure-based lung injury. Additionally, this model is limited by the fact that severely diseased pups may succumb to the exposure because they are not mechanically ventilated. Unfortunately, these mice are not suitable for inclusion in further experimentation, which could produce a survival bias. A survival advantage for mice with intact commensal ecologies may suggest that our demonstration of increased severity of lung injury after MAE underestimates the overall severity of lung injury resulting from commensal disruption.

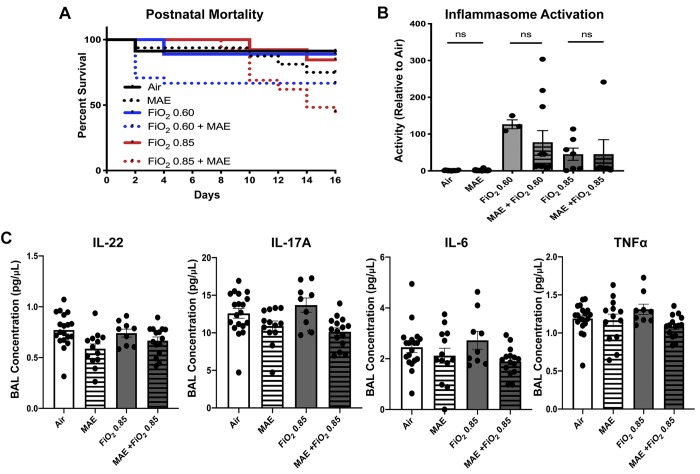

Fig. 4.

Commensal disruption increases mortality and produces changes in some bronchoalveolar lavage (BAL) cytokine levels. A: maternal antibiotic exposure (MAE) leads to increased mortality during hyperoxia exposure [fraction of inspired oxygen () 0.85 compared with MAE and 0.85, log-rank test, P = 0.002]. Normoxia (black), intermediate hyperoxia (blue), and elevated hyperoxia (red), with MAE exposure indicated by a dotted line. B: inflammasome activity is increased by hyperoxia but not by the addition of MAE [two-way ANOVA hyperoxia exposure, P < 0.0001; MAE, not significant (NS)]. C: low-level BAL cytokine concentrations with a limited effect of MAE but not hyperoxia (IL-22: two-way ANOVA interaction, NS; MAE, P = 0.0042; hyperoxia exposure, NS; IL-17A: two-way ANOVA interaction, NS; MAE, P = 0.005; hyperoxia exposure, NS; IL-6: two-way ANOVA interaction, NS; MAE, P = 0.0217; hyperoxia exposure, NS; TNF-α: two-way ANOVA interaction, NS; MAE, P = 0.0396; hyperoxia exposure, NS). Except where noted, error bars represent mean ± SE; n = 7–20 pups/group; data points represent individual animals. Significance was determined by two-way ANOVA, and P < 0.05 was considered significant.

Maternal antibiotic exposure influences neonatal growth.

Antibiotic exposure has a well-described effect on growth in animals (13, 17). In our hands, MAE did not produce a significant difference in the lung-to-body weight ratio in neonatal mice at 15 days of life (Supplemental Fig. S7, A and B). However, MAE did lead to a dose-dependent effect on total body mass of the offspring by 15 days of life (one-way ANOVA, P = 0.004; Supplemental Fig. S5C). This effect was partially countered by exposure to hyperoxia, which produced a wasting effect on total body mass (two-way ANOVA, P = 0.0053; Supplemental Fig. S7C).

Hyperoxia-induced inflammasome activation is not altered by maternal antibiotic exposure.

Because the NLRP3 inflammasome is a critical component of canonical lung injury in BPD (39), we assessed inflammasome activity in lung tissue and noted inflammasome activation was increased by hyperoxia (two-way ANOVA, P < 0.001; Fig. 4B); however, no difference was detected with the addition of MAE [nonsignificant (NS)]. Considered in conjunction with cytokine differences noted in BAL, these results suggest that a different mechanism may be responsible for changes in lung architecture after commensal disruption than has been described for hyperoxia alone.

Maternal antibiotic exposure produces differences in cytokine abundance in bronchoalveolar lavage.

BPD is associated with increased levels of IL-6 and IL-1β and lower concentrations of IL-17A in BAL (2). In particular, IL-1β has recently been expressed in a monocyte-dependent manner (19) and associated with long-term lung injury (27). The IL-17 family is also important as cytokines that link microbial signaling with lung physiology (24). Although BAL concentrations of IL-22 are undescribed in BPD, decreased IL-22 levels in BAL have been associated with impaired lung mucosal immune function in a neonatal mouse model of pneumonia (22). To characterize cytokine differences, we collected BAL at 15 days of life for multiplex cytokine evaluation. MAE decreased IL-17A (two-way ANOVA interaction and hyperoxia, NS; MAE, P = 0.0005; Fig. 4B) and IL-22 in neonatal offspring (two-way ANOVA interaction and hyperoxia, NS; MAE, P = 0.0042; Fig. 4C). IL-6 and TNFα were also reduced by antibiotic exposure (IL-6: two-way ANOVA interaction and hyperoxia, NS; MAE, P = 0.0217; TNFα: two-way ANOVA interaction and hyperoxia, NS; MAE, P = 0.0396). IL-1β was underpowered due to several samples falling below the detection threshold (Supplemental Fig. S5B). These results could suggest that intestinal commensal disruption produces modest reductions in cytokines associated with microbial signaling (IL-22 and IL-17A), as well as altering cytokine production associated more traditionally with hyperoxia (IL-6 and TNFα) at this time point.

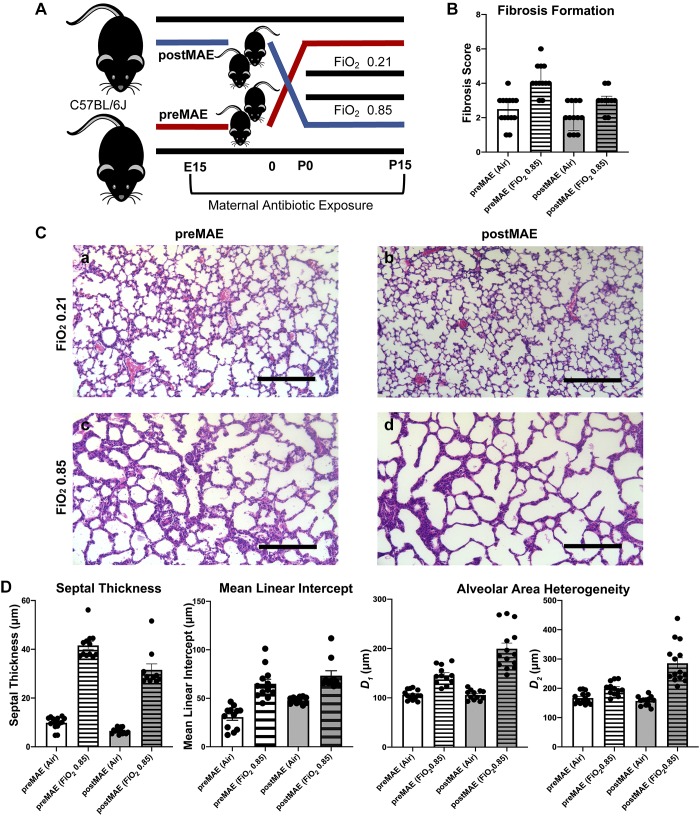

Prenatal maternal antibiotic exposure produces more fibrotic changes than postnatal exposure.

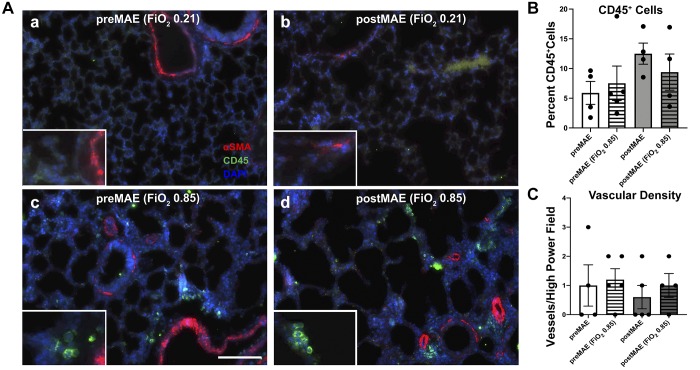

To further clarify the critical exposure period, we performed a crossover experiment (Fig. 5). PreMAE produced a higher grade of fibrosis than postMAE did (Friedman rank sum test, P = 0.00016; Fig. 5B) at both normoxia (Wilcoxon, P = 0.0001) and in combination with exposure to hyperoxia ( 0.85; Wilcoxon, P = 0.002). Correspondingly, preMAE also produced more significant thickening of the interalveolar septa (two-way ANOVA interaction, NS; antibiotics, P = 0.0013; hyperoxia, P < 0.0001; Fig. 5D). However, postMAE led to increases in the Lm (two-way ANOVA interaction, NS; antibiotics, P = 0.0013; hyperoxia, P < 0.0001), D1 (two-way ANOVA interaction, P = 0.0002; antibiotics, P = 0.0003; hyperoxia, P < 0.0001), and D2 (two-way ANOVA interaction, P < 0.0001; antibiotics, P = 0.0002; hyperoxia, P < 0.0001; Fig. 5D). No differences in the Lm, septal thickness or alveolar heterogeneity were noted with the sex of the pups (three-way ANOVA, NS). In comparison with the first experiment, preMAE likely contributes more to the increased septal thickness observed from the combined prenatal and postnatal MAE (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.001; Supplemental Fig. S8A), while postMAE more robustly altered D1 and D2 (one-way ANOVA, P < 0.0001; Supplemental Fig. S8C and one-way ANOVA, P < 0.0001; Supplemental Fig. S8D, respectively) and increased the Lm (one-way ANOVA, P = 0.0276; Supplemental Fig. S8E). Furthermore, although both preMAE and postMAE alter both CD45-positive cell infiltration and capillary density as compared with unexposed mice, no significant differences were observed between preMAE and postMAE in this limited sample (two-way ANOVA, NS; Fig. 6). Considered together, these findings suggest that prenatal exposure may lead to greater fibrosis during later hyperoxia exposure, but postnatal exposure may potentiate lung injury from hyperoxia.

Fig. 5.

Prenatal exposure to maternal antibiotics enhances fibrosis, while postnatal exposure accentuates changes in lung architecture from hyperoxia exposure. A: experimental schema showing the birth of simultaneous litters to either purified water- or antibiotic-exposed dams. The resulting offspring were then fostered to dams in the opposite study arm at birth, before exposure to hyperoxia or normoxia, producing prenatal maternal antibiotic-exposed (preMAE, red) and postnatal maternal antibiotic-exposed (postMAE, blue) cohorts. B: preMAE enhances fibrosis (Friedman rank sum test, P = 0.00016). C: representative micrographs of hematoxylin and eosin-stained lung sections that were gravity inflation-fixed from 15-day-old neonatal mice exposed to either preMAE and normoxia (air, a), preMAE and fraction of inspired oxygen () 0.85 (b), postMAE and normoxia (c), or postMAE and 0.85 (d). D: septal thickness (two-way ANOVA interaction, P = 0.0092; antibiotics and hyperoxia, P < 0.0001) is increased in preMAE, but the mean linear intercept (two-way ANOVA interaction, not significant; antibiotics, P = 0.0013; hyperoxia, P < 0.0001) and weighted means of airway diameter (D1: two-way ANOVA interaction, P = 0.0002; antibiotics, P = 0.0003; hyperoxia, P < 0.0001 and D2: two-way ANOVA interaction, P < 0.0001; antibiotics, P = 0.0002; hyperoxia, P < 0.0001) are increased in postMAE. n = 5–8 pups/group in 2 independent experiments; datapoints represent individual animals, and error bars represent mean ± SE. E15, embryonic day 15; P0, day of birth; P15, postnatal day 15.

Fig. 6.

Prenatal and postnatal maternal antibiotic exposure produce equivalent alterations in pulmonary immune cell recruitment and vascular density. A: representative micrographs for CD45 (Cy5, pseudocolored green channel) and α-smooth muscle actin (αSMA, red channel). a: prenatal maternal antibiotic exposure (preMAE) at normoxia (air). b: postnatal maternal antibiotic exposure (postMAE) at normoxia. c: preMAE at fraction of inspired oxygen () 0.85. d: postMAE at 0.85. B: quantification of the percentage of CD45-positive cells [two-way ANOVA, not significant (NS)]. C: quantification of the number of αSMA-positive vessels <50 μm in diameter per ×20 microscopic field (two-way ANOVA, NS). White scale bar represents 100 μm. n = 3–5 pups/group; datapoints represent individual animals, and error bars display mean ± SE.

DISCUSSION

The intestinal microbiota have the capacity to exert distal effects on the host. This appears to be most relevant during the neonatal period, where it has been proposed that disruption of early commensal colonization of the intestine may produce long-lasting alterations in host metabolic and immune setpoints. Recent evidence suggests that intestinal commensals can influence the lungs (22, 47), a phenomenon called the gut-lung axis (26). However, the mechanisms by which intestinal dysbiosis alters the progression of lung injury and disease remain poorly understood.

Our findings provide evidence that MAE, likely mediated by alterations in intestinal commensal bacteria, can augment the development of lung injury during neonatal life. Early-life antibiotic-associated disruption of intestinal colonization has been associated with increased severity of allergic and infectious lung disease (4, 22), but a role for intestinal commensals in the propagation of lung injury has not been previously demonstrated. We selected BPD as our model system because this disease is the most severe form of newborn lung injury and affects about half of infants born before 28 wk of gestation (51). Furthermore, antibiotic use has been associated with an increased risk of developing BPD in retrospective human cohort studies (4, 22). Because the majority of the microbiome is transferred vertically from mother to offspring (21, 44), we focused on maternal rather than direct exposure to the newborn, as this would allow us to most clearly interrogate the role of early-life colonization. We disrupted neonatal commensal colonization with MAE and profiled how disturbed colonization in the resulting pups altered the development of BPD in these neonatal animals. These experiments showed commensal disruption increased mortality and alteration of pulmonary architecture during exposure to hyperoxia-induced lung injury, characterized by augmented fibrosis, cellular proliferation, and neutrophilic infiltration. Because of the high prevalence of both antibiotic exposure and BPD in preterm newborns, translation to clinical practice may involve reduction in antibiotic administration in the short term and microbiome-altering therapeutics in the future. Furthermore, we noted that preMAE contributed to the formation of hyperoxia-induced fibrosis even when pups were reared with dams with an intact microbiota after birth. In contrast, the postMAE in pups born to dams with intact commensal ecology contributed to hyperoxia exposure-induced lung injury, suggesting that perinatal MAE alters lung injury and that the effects may vary depending on the timing of exposure.

As evidence of the importance for the microbiome in immune and pulmonary development has increased, considerable interest has arisen in the role of the microbiome in the development of BPD. However, the focus to date has been on the airway microbiome. The gut microbiota may exhibit a wide range of extraintestinal effects, as highlighted by alterations in pulmonary development and body weight in our model. A recent systematic review was able to identify six studies of the airway microbiome, but none that explored the intestinal microbiome in BPD. Unfortunately, these studies also had significant heterogeneity in methodologic approaches and clinical characteristics, which makes drawing more systematic conclusions difficult. Moreover, although differences in the airway microbiome are beginning to be understood in BPD (37), only one study has examined the gut microbiome in BPD (8). This cohort showed that fecal volatile organic compounds, potentially arising from metabolites produced by intestinal commensals, predicted which infants would develop BPD. However, when these authors attempted to demonstrate differences in the intestinal microbiome at 28 days of life, they were unable to detect a difference (8). Taken together, these studies demonstrate that while differences in the airway microbiome may result during the development of BPD, the role of the intestinal microbiome is still unknown. Our study provides valuable experimental evidence that manipulation of the gut microbiota by antibiotic exposure influences the progression of lung injury. While there are significant differences between the mouse and human microbiome, our work provides mechanistic insights that may assist in the interpretation of future observational studies in human newborns examining the role of the gut-lung axis in BPD.

Another important finding of our work is the demonstration that neonatal commensal disruption produces pulmonary fibrosis. Although it is known that idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis may be affected by the microbiome (25, 30), these experiments are the first demonstration that intestinal commensal organisms may play a role in fibrosis formation from hyperoxia-induced lung injury. Pulmonary fibrosis is a classic component of severe BPD (16), but it is less prevalent in modern postsurfactant disease (15) because changes in clinical management have led to a disease characterized by diffuse, milder injury. If intestinal commensal ecology contributes to the development of pulmonary fibrosis in preterm infants as our data suggest, this finding could have significant implications for clinical management. Our data suggest that antibiotic-induced commensal disruption may increase the severity of BPD by promoting pulmonary fibrosis and imply that by limiting perinatal antibiotic exposure, we may be able to lower the prevalence of clinically severe disease.

We also demonstrated that commensal disruption reduced the pulmonary vasculature density. Lung injury inhibits the function and maturation of the pulmonary vasculature (5), with the most striking changes in the musculature of small arteries, which lead to increased vascular resistance (35). A surprising finding of these studies was that MAE not only potentiated a reduction in the vascular density from hyperoxia, but that MAE alone was sufficient to produce alterations in vascular development even under normoxic conditions. Reduced pulmonary vascular density is a critical characteristic of BPD that is linked to the development of pulmonary hypertension, a severe complication of chronic lung disease that markedly increases the risk for mortality from BPD (36). The contribution of commensal disruption to the development of pulmonary hypertension has profound implications for the mortality of BPD that are worthy of further investigation and may play a role in the progression of other pulmonary diseases as well. While our data do not permit us to identify the cause of increased mortality in our experiments, these findings could be related to an increased prevalence of pulmonary hypertension.

Our data support a role of the intestinal microbiome in experimental BPD and provide foundational evidence for a role of the gut-lung axis in neonatal lung injury. We identified a characteristic disruption in commensal ecology resulting from MAE and demonstrated that this resulted in a more severe phenotype of BPD characterized by increased mortality and pulmonary fibrosis as well as decreased pulmonary vascular density. We identified alterations in microbial abundance with biomarker and therapeutic potential, and mechanistically we showed that these differences were associated with reduced expression of IL-22 without differences in inflammasome activation. Building on the differences highlighted by our prenatal and postnatal MAE exposure experiments, utilizing fecal microbiota transfer or gnotobiotic mice may present an insightful avenue for further research. Together, our findings establish the importance of the intestinal commensal bacteria to the development of BPD and provide insights for the rational design of microbial-derived therapeutics for the most severe pulmonary complication of prematurity.

GRANTS

This work was supported by the 2018 Marshall Klaus Perinatal Research Award for Basic or Clinical Science from the American Academy of Pediatrics, Section on Neonatal-Perinatal Medicine, the 2018 Excellence in Research Grant and the Society for Pediatric Research Fellow’s Basic Research Award (to K. A. Willis), by National Institutes of Health (NIH) Grants R01-AI-090050, R01-ES-015050, and P42-ES-013649 (to S. A. Cormier) and R01-DK-117183 (to A. Bajwa), and the Division of Neonatology at University of Tennessee Health Science Center.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

K.A.W., J.F.P., S.A.C., and A.J.T. conceived and designed research; K.A.W., D.T.S., M.M.A., C.T.W., N.M., C.K.G., and A.B. performed experiments; K.A.W., D.T.S., A.B., J.F.P., S.A.C., and A.J.T. analyzed data; K.A.W., J.F.P., S.A.C., and A.J.T. interpreted results of experiments; K.A.W. and J.F.P. prepared figures; K.A.W. drafted manuscript; K.A.W., M.M.A., A.B., J.F.P., S.A.C., and A.J.T. edited and revised manuscript; K.A.W., D.T.S., M.M.A., C.T.W., N.M., C.K.G., A.B., J.F.P., S.A.C., and A.J.T. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dahui You for assistance during the initial phase of this project and Bhavya Kadiyala for assistance with the statistical analysis.

REFERENCES

- 1.Alvira CM. Aberrant pulmonary vascular growth and remodeling in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Front Med (Lausanne) 3: 21, 2016. doi: 10.3389/fmed.2016.00021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ambalavanan N, Carlo WA, D’Angio CT, McDonald SA, Das A, Schendel D, Thorsen P, Higgins RD; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network . Cytokines associated with bronchopulmonary dysplasia or death in extremely low birth weight infants. Pediatrics 123: 1132–1141, 2009. doi: 10.1542/peds.2008-0526. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arboleya S, Sánchez B, Milani C, Duranti S, Solís G, Fernández N, de los Reyes-Gavilán CG, Ventura M, Margolles A, Gueimonde M. Intestinal microbiota development in preterm neonates and effect of perinatal antibiotics. J Pediatr 166: 538–544, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2014.09.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Arrieta MC, Stiemsma LT, Dimitriu PA, Thorson L, Russell S, Yurist-Doutsch S, Kuzeljevic B, Gold MJ, Britton HM, Lefebvre DL, Subbarao P, Mandhane P, Becker A, McNagny KM, Sears MR, Kollmann T, Mohn WW, Turvey SE, Finlay BB; CHILD Study Investigators . Early infancy microbial and metabolic alterations affect risk of childhood asthma. Sci Transl Med 7: 307ra152, 2015. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aab2271. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Baker CD, Abman SH. Impaired pulmonary vascular development in bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Neonatology 107: 344–351, 2015. doi: 10.1159/000381129. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Barfod KK, Roggenbuck M, Al-Shuweli S, Fakih D, Sørensen SJ, Sørensen GL. Alterations of the murine gut microbiome in allergic airway disease are independent of surfactant protein D. Heliyon 3: e00262, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.heliyon.2017.e00262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Becattini S, Taur Y, Pamer EG. Antibiotic-induced changes in the intestinal microbiota and disease. Trends Mol Med 22: 458–478, 2016. doi: 10.1016/j.molmed.2016.04.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Berkhout DJ, Niemarkt HJ, Benninga MA, Budding AE, van Kaam AH, Kramer BW, Pantophlet CM, van Weissenbruch MM, de Boer NK, de Meij TG. Development of severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia is associated with alterations in fecal volatile organic compounds. Pediatr Res 83: 412–419, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cantey JB, Huffman LW, Subramanian A, Marshall AS, Ballard AR, Lefevre C, Sagar M, Pruszynski JE, Mallett LH. Antibiotic exposure and risk for death or bronchopulmonary dysplasia in very low birth weight infants. J Pediatr 181: 289–293.e1, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2016.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chen S, Rong M, Platteau A, Hehre D, Smith H, Ruiz P, Whitsett J, Bancalari E, Wu S. CTGF disrupts alveolarization and induces pulmonary hypertension in neonatal mice: implication in the pathogenesis of severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 300: L330–L340, 2011. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00270.2010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chen Y, Yu Q, Xu CB. A convenient method for quantifying collagen fibers in atherosclerotic lesions by ImageJ software. Int J Clin Exp Med 10: 14904–14910, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Chinen T, Rudensky AY. The effects of commensal microbiota on immune cell subsets and inflammatory responses. Immunol Rev 245: 45–55, 2012. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-065X.2011.01083.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cho I, Yamanishi S, Cox L, Methé BA, Zavadil J, Li K, Gao Z, Mahana D, Raju K, Teitler I, Li H, Alekseyenko AV, Blaser MJ. Antibiotics in early life alter the murine colonic microbiome and adiposity. Nature 488: 621–626, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nature11400. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Clemente JC, Ursell LK, Parfrey LW, Knight R. The impact of the gut microbiota on human health: an integrative view. Cell 148: 1258–1270, 2012. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.01.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Coalson JJ. Pathology of new bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Semin Neonatol 8: 73–81, 2003. doi: 10.1016/S1084-2756(02)00193-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Coalson JJ. Pathology of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Semin Perinatol 30: 179–184, 2006. doi: 10.1053/j.semperi.2006.05.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Cox LM, Yamanishi S, Sohn J, Alekseyenko AV, Leung JM, Cho I, Kim SG, Li H, Gao Z, Mahana D, Zárate Rodriguez JG, Rogers AB, Robine N, Loke P, Blaser MJ. Altering the intestinal microbiota during a critical developmental window has lasting metabolic consequences. Cell 158: 705–721, 2014. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2014.05.052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dethlefsen L, Huse S, Sogin ML, Relman DA. The pervasive effects of an antibiotic on the human gut microbiota, as revealed by deep 16S rRNA sequencing. PLoS Biol 6: e280, 2008. doi: 10.1371/journal.pbio.0060280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Eldredge LC, Creasy RS, Presnell S, Debley JS, Juul SE, Mayock DE, Ziegler SF. Infants with evolving bronchopulmonary dysplasia demonstrate monocyte-specific expression of IL-1 in tracheal aspirates. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 317: L49–L56, 2019. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00060.2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Esaiassen E, Fjalstad JW, Juvet LK, van den Anker JN, Klingenberg C. Antibiotic exposure in neonates and early adverse outcomes: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J Antimicrob Chemother 72: 1858–1870, 2017. doi: 10.1093/jac/dkx088. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ferretti P, Pasolli E, Tett A, Asnicar F, Gorfer V, Fedi S, Armanini F, Truong DT, Manara S, Zolfo M, Beghini F, Bertorelli R, De Sanctis V, Bariletti I, Canto R, Clementi R, Cologna M, Crifò T, Cusumano G, Gottardi S, Innamorati C, Masè C, Postai D, Savoi D, Duranti S, Lugli GA, Mancabelli L, Turroni F, Ferrario C, Milani C, Mangifesta M, Anzalone R, Viappiani A, Yassour M, Vlamakis H, , et al. Mother-to-infant microbial transmission from different body sites shapes the developing infant gut microbiome. Cell Host Microbe 24: 133–145.e5, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2018.06.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gray J, Oehrle K, Worthen G, Alenghat T, Whitsett J, Deshmukh H. Intestinal commensal bacteria mediate lung mucosal immunity and promote resistance of newborn mice to infection. Sci Transl Med 9: eaaf9412, 2017. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf9412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gulati R, Elabiad MT, Dhanireddy R, Talati AJ. Trends in medication use in very low-birth-weight infants in a level 3 NICU over two decades. Am J Perinatol 33: 370–377, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gurczynski SJ, Moore BB. IL-17 in the lung: the good, the bad, and the ugly. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 314: L6–L16, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00344.2017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Han MK, Zhou Y, Murray S, Tayob N, Noth I, Lama VN, Moore BB, White ES, Flaherty KR, Huffnagle GB, Martinez FJ; COMET Investigators . Lung microbiome and disease progression in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis: an analysis of the COMET study. Lancet Respir Med 2: 548–556, 2014. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(14)70069-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He Y, Wen Q, Yao F, Xu D, Huang Y, Wang J. Gut-lung axis: The microbial contributions and clinical implications. Crit Rev Microbiol 43: 81–95, 2017. doi: 10.1080/1040841X.2016.1176988. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hogmalm A, Bry M, Bry K. Pulmonary IL-1β expression in early life causes permanent changes in lung structure and function in adulthood. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 314: L936–L945, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00256.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hooper LV, Littman DR, Macpherson AJ. Interactions between the microbiota and the immune system. Science 336: 1268–1273, 2012. doi: 10.1126/science.1223490. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Hsieh EM, Hornik CP, Clark RH, Laughon MM, Benjamin DK Jr, Smith PB; Best Pharmaceuticals for Children Act—Pediatric Trials Network . Medication use in the neonatal intensive care unit. Am J Perinatol 31: 811–821, 2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huang Y, Ma SF, Espindola MS, Vij R, Oldham JM, Huffnagle GB, Erb-Downward JR, Flaherty KR, Moore BB, White ES, Zhou T, Li J, Lussier YA, Han MK, Kaminski N, Garcia JG, Hogaboam CM, Martinez FJ, Noth I; COMET-IPF Investigators . Microbes are associated with host innate immune response in idiopathic pulmonary fibrosis. Am J Respir Crit Care Med 196: 208–219, 2017. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201607-1525OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hübner RH, Gitter W, El Mokhtari NE, Mathiak M, Both M, Bolte H, Freitag-Wolf S, Bewig B. Standardized quantification of pulmonary fibrosis in histological samples. Biotechniques 44: 507–517, 2008. doi: 10.2144/000112729. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Jacob RE, Carson JP, Gideon KM, Amidan BG, Smith CL, Lee KM. Comparison of two quantitative methods of discerning airspace enlargement in smoke-exposed mice. PLoS One 4: e6670, 2009. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0006670. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Jensen EA, Schmidt B. Epidemiology of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Birth Defects Res A Clin Mol Teratol 100: 145–157, 2014. doi: 10.1002/bdra.23235. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Clark JA, Coopersmith CM. Intestinal crosstalk: a new paradigm for understanding the gut as the “motor” of critical illness. Shock 28: 384–393, 2007. doi: 10.1097/shk.0b013e31805569df. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kinsella JP, Greenough A, Abman SH. Bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Lancet 367: 1421–1431, 2006. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(06)68615-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lagatta JM, Hysinger EB, Zaniletti I, Wymore EM, Vyas-Read S, Yallapragada S, Nelin LD, Truog WE, Padula MA, Porta NFM, Savani RC, Potoka KP, Kawut SM, DiGeronimo R, Natarajan G, Zhang H, Grover TR, Engle WA, Murthy K; Children’s Hospital Neonatal Consortium Severe BPD Focus Group . The impact of pulmonary hypertension in preterm infants with severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia through 1 year. J Pediatr 203: 218–224.e3, 2018. doi: 10.1016/j.jpeds.2018.07.035. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lal CV, Kandasamy J, Dolma K, Ramani M, Kumar R, Wilson L, Aghai Z, Barnes S, Blalock JE, Gaggar A, Bhandari V, Ambalavanan N. Early airway microbial metagenomic and metabolomic signatures are associated with development of severe bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol 315: L810–L815, 2018. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.00085.2018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Levy M, Kolodziejczyk AA, Thaiss CA, Elinav E. Dysbiosis and the immune system. Nat Rev Immunol 17: 219–232, 2017. doi: 10.1038/nri.2017.7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Liao J, Kapadia VS, Brown LS, Cheong N, Longoria C, Mija D, Ramgopal M, Mirpuri J, McCurnin DC, Savani RC. The NLRP3 inflammasome is critically involved in the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Nat Commun 6: 8977, 2015. doi: 10.1038/ncomms9977. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Marsland BJ, Trompette A, Gollwitzer ES. The gut–lung axis in respiratory disease. Ann Am Thorac Soc 12, Suppl 2: S150–S156, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Maynard CL, Elson CO, Hatton RD, Weaver CT. Reciprocal interactions of the intestinal microbiota and immune system. Nature 489: 231–241, 2012. doi: 10.1038/nature11551. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mitzner W, Fallica J, Bishai J. Anisotropic nature of mouse lung parenchyma. Ann Biomed Eng 36: 2111–2120, 2008. doi: 10.1007/s10439-008-9538-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Miyoshi J, Bobe AM, Miyoshi S, Huang Y, Hubert N, Delmont TO, Eren AM, Leone V, Chang EB. Peripartum antibiotics promote gut dysbiosis, loss of immune tolerance, and inflammatory bowel disease in genetically prone offspring. Cell Reports 20: 491–504, 2017. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.06.060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Moeller AH, Suzuki TA, Phifer-Rixey M, Nachman MW. Transmission modes of the mammalian gut microbiota. Science 362: 453–457, 2018. doi: 10.1126/science.aat7164. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Nardiello C, Mižíková I, Silva DM, Ruiz-Camp J, Mayer K, Vadász I, Herold S, Seeger W, Morty RE. Standardisation of oxygen exposure in the development of mouse models for bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Dis Model Mech 10: 185–196, 2017. doi: 10.1242/dmm.027086. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Novitsky A, Tuttle D, Locke RG, Saiman L, Mackley A, Paul DA. Prolonged early antibiotic use and bronchopulmonary dysplasia in very low birth weight infants. Am J Perinatol 32: 43–48, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46a.R Core Team R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing. Vienna, Austria: R Foundation for Statistical Computing, 2013. https://www.r-project.org. [Google Scholar]

- 47.Russell SL, Gold MJ, Hartmann M, Willing BP, Thorson L, Wlodarska M, Gill N, Blanchet MR, Mohn WW, McNagny KM, Finlay BB. Early life antibiotic-driven changes in microbiota enhance susceptibility to allergic asthma. EMBO Rep 13: 440–447, 2012. doi: 10.1038/embor.2012.32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Russell SL, Gold MJ, Reynolds LA, Willing BP, Dimitriu P, Thorson L, Redpath SA, Perona-Wright G, Blanchet MR, Mohn WW, Finlay BB, McNagny KM. Perinatal antibiotic-induced shifts in gut microbiota have differential effects on inflammatory lung diseases. J Allergy Clin Immunol 135: 100–109.e5, 2015. doi: 10.1016/j.jaci.2014.06.027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Samuelson DR, Welsh DA, Shellito JE. Regulation of lung immunity and host defense by the intestinal microbiota. Front Microbiol 6: 1085, 2015. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2015.01085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Schirmer M, Smeekens SP, Vlamakis H, Jaeger M, Oosting M, Franzosa EA, Ter Horst R, Jansen T, Jacobs L, Bonder MJ, Kurilshikov A, Fu J, Joosten LA, Zhernakova A, Huttenhower C, Wijmenga C, Netea MG, Xavier RJ. Linking the human gut microbiome to inflammatory cytokine production capacity. Cell 167: 1125–1136.e8, 2016. [Erratum in Cell 167: 1897, 2016.] doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Stoll BJ, Hansen NI, Bell EF, Shankaran S, Laptook AR, Walsh MC, Hale EC, Newman NS, Schibler K, Carlo WA, Kennedy KA, Poindexter BB, Finer NN, Ehrenkranz RA, Duara S, Sánchez PJ, O’Shea TM, Goldberg RN, Van Meurs KP, Faix RG, Phelps DL, Frantz ID III, Watterberg KL, Saha S, Das A, Higgins RD; Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Neonatal Research Network . Neonatal outcomes of extremely preterm infants from the NICHD Neonatal Research Network. Pediatrics 126: 443–456, 2010. doi: 10.1542/peds.2009-2959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Vissers M, de Groot R, Ferwerda G. Severe viral respiratory infections: are bugs bugging? Mucosal Immunol 7: 227–238, 2014. doi: 10.1038/mi.2013.93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]