Abstract

Influenza A virus nucleoprotein (NP) is a structural component that encapsulates the viral genome into the form of ribonucleoprotein complexes (vRNPs). Efficient assembly of vRNPs is critical for the virus life cycle. The assembly routes from RNA-free NP to the NP-RNA polymer in vRNPs has been suggested to require a cellular factor UAP56, but the mechanism is poorly understood. Here, we characterized the interaction between NP and UAP56 using recombinant proteins. We showed that UAP56 features two NP binding sites. In addition to the UAP56 core comprised of two RecA domains, we identified the N-terminal extension (NTE) of UAP56 as a previously unknown NP binding site. In particular, UAP56-NTE recognizes the nucleic acid binding region of NP. This corroborates our observation that binding of UAP56-NTE and RNA to NP is mutually exclusive. Collectively, our results reveal the molecular basis for how UAP56 acts on RNA-free NP, and provide new insights into NP-mediated influenza genome packaging.

Keywords: mRNA nuclear export, influenza A virus, host-pathogen interaction, DEAD-box ATPase, RNA-binding protein

Introduction

Influenza A virus is the primary cause of seasonal flu epidemics and remains a major threat to worldwide public health [1, 2]. The viral genome is comprised of eight negative-sense RNA segments [3–5]. Each RNA segment is encapsulated by many copies of nucleoprotein (NP) and bound by the viral polymerase to form ribonucleoprotein complexes (vRNPs). Electron microscopy analyses of vRNP isolated from virions demonstrated that the vRNP has an antiparallel double-helical structure formed by NP-coated vRNA, with the 5’ and 3’ termini of vRNA bound to the viral polymerase [6]. vRNPs serve as the template for transcription and replication within the cell nucleus. It has been suggested that during viral replication the viral polymerase binds to the 5’ end of the nascent vRNA and recruits the first NP molecule [7–10]. Additional NP molecules are then successively added via NP-RNA interaction and NP-NP oligomerization. To date, the precise mechanism of NP-mediated virus genome packaging is still poorly understood.

Evidence suggests that the cellular factor UAP56 facilitates encapsulation of nascent RNA by NP [11–13]. As a member of the DEAD-box family of RNA-dependent ATPases [14], UAP56 plays critical roles in RNA processing and export [15–17]. For example, UAP56 mediates nuclear mRNA export by recruiting export factors to the mRNA [18–20]. Initial evidence of the NP-UAP56 interaction came from a yeast two-hybrid screen of a human cDNA library using influenza A/PR/8 NP protein as bait [11]. The core fragment (a.a. 60-428) of UAP56 was identified as an NP interacting protein. In an independent study, UAP56 was fractionated from HeLa cell nuclear extracts and identified as a factor that stimulates influenza virus RNA synthesis in a cell-free system [12]. Intriguingly, UAP56 was shown to facilitate binding of NP to RNA in vitro, while UAP56 itself did not associate with the NP•RNA complex [12, 21]. Collectively, UAP56 has been suggested to facilitate viral RNP packaging by promoting NP-RNA interaction. However, the molecular basis of the NP-UAP56 interaction is not known.

Here, we characterized the interaction between UAP56 and influenza NP using recombinant proteins. We found that UAP56 features two NP binding sites. Both the N-terminal extension (NTE) and the core comprised of two RecA-like domains are capable of binding NP. Using cross-linking mass spectrometry, we identified the binding site of UAP56-NTE to be the basic groove situated between the head and body domains of NP. Interestingly, this basic groove is also critical for NP-RNA interaction, and we showed that UAP56-NTE and RNA compete for binding to NP. Together, our results demonstrate that UAP56-NTE recognizes the nucleic acid binding region of influenza NP and provide new insights into the role of UAP56 in influenza A virus genome packaging.

Materials and methods

The details of plasmids, protein purifications, GST pull down, electrophoretic mobility shift assay, and crosslinking mass spectrometry are described in the supplementary information.

Results

The N-terminal extension of UAP56 features a previously unknown NP binding site

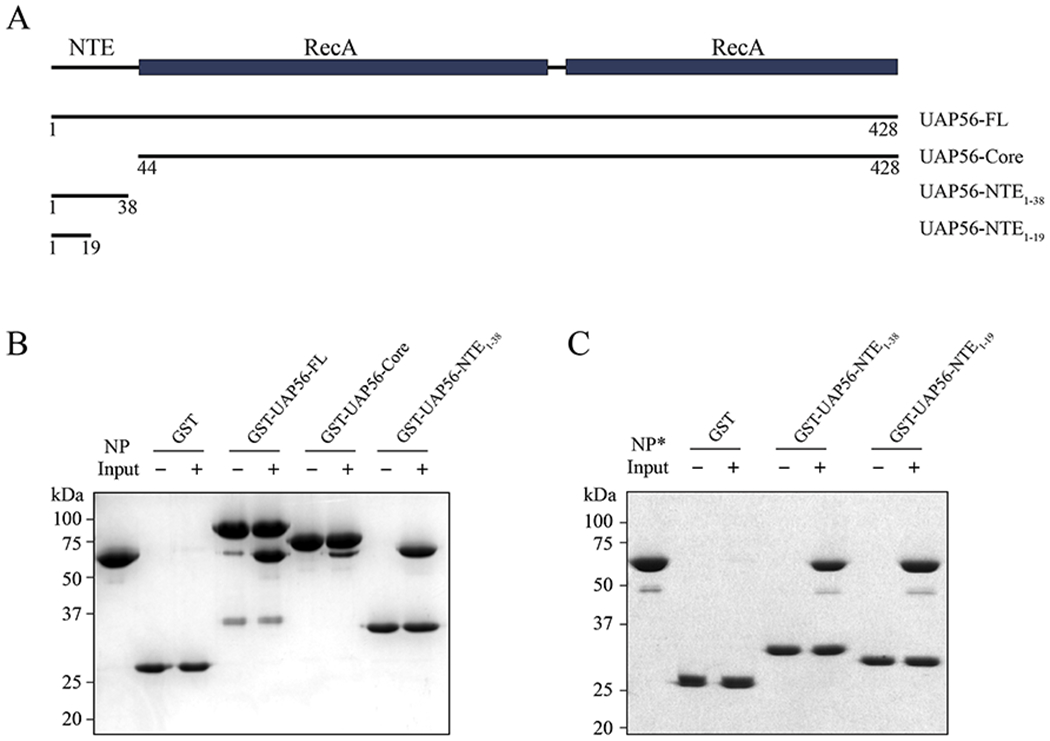

UAP56 contains an NTE and a core comprised of two RecA-like domains (Fig. 1A) [22]. To dissect the NP-UAP56 interaction, we generated various GST-tagged UAP56 proteins including UAP56-FL (a.a. 1-428), UAP56-NTE1-38 (a.a. 1-38), and UAP56-Core (a.a. 44-428). We showed the interaction between UAP56-FL and influenza A/PR/8 NP using GST pull-down assays (Fig. 1B and Fig. S1A, B). Interestingly, both UAP56-NTE and UAP56-Core are capable of binding to NP. UAP56-Core interaction with NP is in agreement with the previous yeast two-hybrid screen that identified UAP56 (a.a. 60-428) as an influenza A/PR/8 NP interacting protein [11]. On the other hand, UAP56-NTE is a previously unknown binding site for NP, and UAP56-NTE seems to be a stronger binding site compared to UAP56-Core (Fig. 1B). These observations prompt us to further explore the underlying molecular basis for UAP56-NTE interaction with NP.

Figure 1.

UAP56 features two binding sites for influenza NP protein. (A) Schematic representation of UAP56. Recombinant protein fragments that were used for GST pull-down assays are indicated. (B) In vitro GST pull-down assays with various GST-tagged UAP56 proteins and influenza A/PR/8 NP protein. (C) In vitro GST pull-down assays with GST-UAP56-NTEs and the monomeric NP-R416A mutant (NP*). All experiments (B-C) were repeated three times independently.

Mapping the UAP56-NTE – NP interaction with crosslinking mass spectrometry

We sought to map the NP binding site of UAP56-NTE by crosslinking mass spectrometry (XL-MS). In designing an optimal reaction system for the XL-MS experiments, we took into consideration that purified recombinant influenza NP exists as monomers and small oligomers (trimers and tetramers) [8, 23]. This oligomerization of NP is mediated by an extended tail loop (a.a. 402-428). We used a well characterized monomeric NP-R416A mutant due to its superior solubility and homogeneity (designated as NP*) [8]. Importantly, UAP56-NTE1-38 retained the ability to bind NP* (Fig. 1C). Of note, it was reported that UAP56 did not bind to monomeric NP* using gel filtration chromatography [21], but we have shown here that the interaction is retained using the less stringent GST pull down assay. We further narrowed down the NP binding site on UAP56-NTE1-38 to the N-terminal 19 residues (designated as UAP56-NTE1-19) (Fig. 1C and Fig. S1A). EDC, a carboxyl- and amine-reactive crosslinker, was used to crosslink NP* and UAP56-NTE1-19. UAP56-NTE1-19 is highly acidic, featuring ten Glu and Asp residues in total, while NP is conversely enriched with a large number of basic residues including 21 lysine residues in influenza A/PR/8 NP. Thus, EDC is ideally suited to activate carboxyl groups (ten Glu or Asp, and C-terminus) in UAP56-NTE1-19 for crosslinking to primary amines (Lys and N-terminus) in NP. UAP56-NTE1-19 chemically synthesized with a FITC fluorophore at the N-terminus was used for the crosslinking reaction to examine the crosslinking efficiency. We optimized a protocol to use combined trypsin and Asp-N digestion to produce peptides for LC-MS/MS analysis.

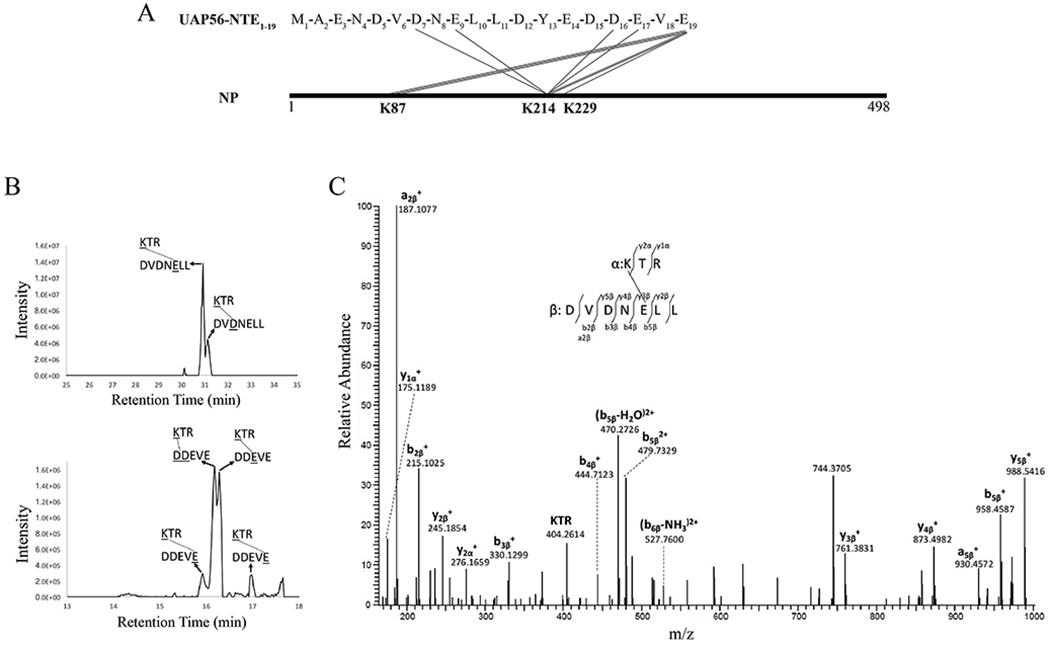

We identified K214 as a major crosslinked site on NP* from EDC-crosslinked NP* and FITC-UAP56-NTE1-19 (Fig. 2A) by using StavroX software [24] designed to identify crosslinked peptides from LC-MS/MS data. Different residues on UAP56-NTE1-19 can be crosslinked with K214 on NP*; selected ion chromatograms for corresponding crosslinked peptides are shown in Fig. 2B. The tandem mass spectrum for one crosslinked peptide (K*TR-DVDNE*LL) is shown in Fig 2C. The data suggest that crosslinking is more efficient around residue E9 (Fig 2B, left panel) on UAP56-NTE1-19, as judged by the intensity of ion chromatograms. However, caution must be taken given that ionization differences between peptides can be large. There are two peaks for K214 crosslinked with the last residue E19 on UAP56-NTE1-19 (Fig 2B, right panel), which are probably due to amide bond formation through either the carboxyl terminal or the side chain carboxyl group of E19. In addition to the K214 crosslinked sites identified by StavroX, searches for UAP56-NTE1-19 peptide modification by the NP* protein on each peptide predicted for Asp-N digestion combined with manual verification yielded three additional crosslinked peptides including K87 on NP* crosslinked to E19 on UAP56-NTE1-19. The signal for these crosslinked peptides was weak compared with crosslinking on K214 residue (data not shown). Another peptide corresponding to crosslinking of K229 on NP* with E19 on UAP56-NTE1-19 was detected in one of the two analyses; however, the signal for this peptide was very weak (data not shown), which may be due to nonspecific crosslinking. No other lysine residues on NP* were detected as crosslinked to UAP56-NTE1-19. All identified crosslinked peptides are listed in Table 1.

Figure 2.

XL-MS analysis of the interaction between NP and UAP56-NTE. (A) Identified intermolecular cross-links between UAP56-NTE1-19 and NP* by the EDC crosslinker. Each line represents a unique crosslinking site. (B) Selected ion chromatograms for crosslinked peptides involving K214 of NP*. (C) Tandem mass spectrum for crosslinked peptide K*TR-DVDNE*LL.

Table 1.

EDC-crosslinked peptides between NP* and FITC-UAP56-NTE1-19

| Peptide | [MH]+calc | [MH]+exp | Error(ppm) | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| NP* peptide | UAP56 peptide | |||

| 214-216: K*TR | DVDNE*LL | 1202.6375 | 1202.6392 | 1.41 |

| 214-216: K*TR | DVD*NELL | 1202.6375 | 1202.6392 | 1.41 |

| 214-216: K*TR | DDEVE*(1) | 991.4691 | 991.4705 | 1.41 |

| 214-216: K*TR | DDE*VE | 991.4691 | 991.4686 | 0.50 |

| 214-216: K*TR | (DD)*EVE | 991.4691 | 991.4697 | 0.61 |

| 214-216: K*TR | DDEVE*(2) | 991.4691 | 991.4663 | 2.82 |

| 78-90: YLEEHPSAGK*DPK | DYEDDEVE* | 2465.0627 | 2465.0617 | 0.41 |

| 78-91: YLEEHPSAGK*DPKK | DYEDDEVE* | 2593.1576 | 2593.1585 | 0.35 |

| 76-91: NKYLEEHPSAGK*DPKK | DYEDDEVE* | 2835.2955 | 2835.2940 | 0.53 |

| 228-236: GK*FQTAAQK | DYEDDEVE* | 1972.8771 | 1972.8740 | 1.57 |

Asterisk (*) indicates the residues involved in crosslinking. All masses are monoisotopic masses.

UAP56-NTE recognizes nucleic acid binding site of NP

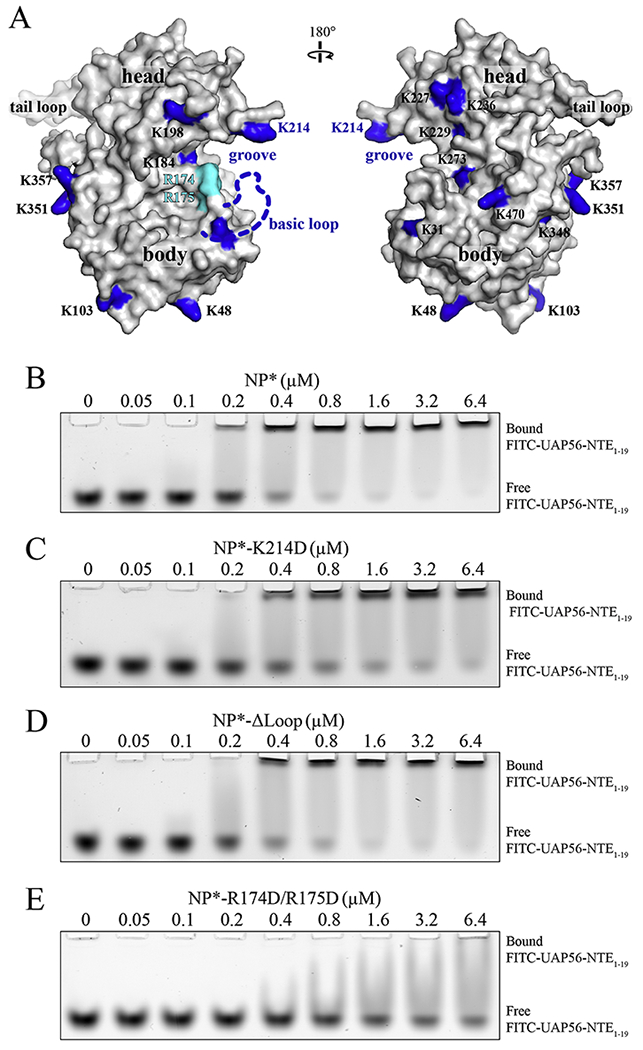

We mapped the crosslinked lysine residues onto the structure of NP (Fig. 3A). NP is composed of a head domain, a body domain, and a tail loop. K214 sits on an exposed position at an alpha-helix in the head domain, while K87 is located on a basic loop (a.a. 72-91) in the body domain, which is missing in the model due to flexibility. To examine the role of NP K214 and K87 residues in binding to UAP56, we purified NP*-K214D and NP*-Δloop (a.a. 74-88 replaced by a Gly-Ser linker) mutants. We examined the interaction with the fluorescent labeled FITC-UAP56-NTE1-19 by EMSA. NP* directly bound to FITC-UAP56-NTE1-19 with an affinity in the low micromolar range (Fig. 3B). Mutation of K214 or deletion of the basic loop containing K87 did not significantly reduce the interaction between NP* and FITC-UAP56-NTE1-19 (Fig. 3C, D, and Fig. S1B). These findings, together with our XL-MS studies (Fig. 2), suggest that K214 and K87 are in close proximity to the NP*-UAP56 interface, but not critical for the their interaction.

Figure 3.

UAP56-NTE binds to the basic groove of NP. (A) Distribution of lysine residues on the surface of a single NP molecule. Lysine residues, based on the sequence of influenza A/PR/8 NP, are labeled on a surface representation of the highly homologous influenza A/WSN/33 NP protein (PDB 2IQH). Figure was generated by PyMOL [37]. (B-E) EMSA assay of FITC-labeled UAP56-NTE1-19 binding to NP* (B), NP*-K214D (C), NP*-Δloop (D), and NP*-R174D/R175D (E). All experiments (B-E) were repeated three times independently.

We noted that both NP* K87 and K214 residues are located in the periphery of a basic groove situated between the NP head and body domains (Fig. 3A). Thus, the basic groove sits on the binding path of UAP56-NTE1-19. We speculated that the residues at the center of the groove, such as R174 and R175, may be involved in the UAP56-NTE1-19 interaction. R174 and R175 would not be identified in our XL-MS experiments because the EDC crosslinker only reacts with primary amines like lysine residues. To test our hypothesis, we purified the NP*-R174D/R175D mutant. Indeed, mutations of NP R174 and R175 had a more significant impact on UAP56-NTE1-19 binding to NP*, as compared to NP*-K214D and NP*-Δloop (Fig. 3E and Fig. S1B). Together, our XL-MS results and mutagenesis studies demonstrate that UAP56-NTE1-19 recognizes the basic groove between the NP head and body domains.

Binding of UAP56-NTE and RNA to NP is mutually exclusive

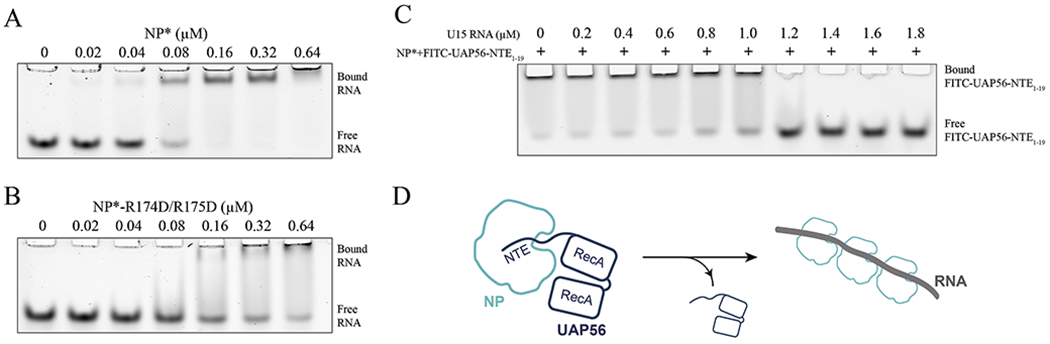

A plethora of studies have shown that the basic groove of NP where UAP56-NTE1-19 binds is critical for NP-RNA interaction [23, 25]. NP interacts with single-stranded RNA in solution without apparent sequence specificity [26]. This is consistent with its role as a general genome packaging factor. To date, atomic resolution structure of influenza vRNP is still lacking, therefore, the precise NP-RNA binding mode in vRNP is not known. We examined NP*-RNA interaction using a fluorescently labeled U15 RNA oligomer. NP* shifted the RNA band to lower mobility, indicating the formation of a NP*•RNA complex (Fig. 4A). R174D/R175D mutant of NP* had the most significant impact on NP*-RNA interaction compared to K214D and Δloop mutants (Fig. 4B and Fig. S2A, 2B). Interestingly, differential effects of NP*-Δloop mutant on UAP56 and RNA binding were observed. While NP*-Δloop did not obviously affect UAP56 binding (Fig. 3B and 3D), it reduced NP*-RNA interaction (Fig. 4A and Fig. S2B).

Figure 4.

Binding of UAP56-NTE and RNA to NP* is mutually exclusive. (A-B) EMSA assay of Alexa 488-labeled U15 RNA binding to NP* (A) and NP*-R174D/R175D (B). (C) U15 RNA displaced FITC-UAP56-NTE1-19 from the NP*•UAP56-NTE1-19 complex in a concentration dependent manner. All experiments (A-C) were repeated three times independently. (D) Working model of how UAP56 facilitates NP-mediated influenza genome packaging. Our results suggest that UAP56 initially acts on RNA-free NP through interactions with both NTE and the core of UAP56. Such configurations may prime NP for RNA interaction. Upon NP deposition on viral RNA, UAP56 is displaced due to the mutually exclusive binding of UAP56-NTE and RNA to NP.

The above observation strongly suggests that UAP56-NTE1-19 and RNA bind to overlapping regions on NP*, and the basic groove of NP is critical for both UAP56 and RNA interaction. Indeed, we found that U15 RNA competed with FITC-UAP56-NTE1-19 for binding to NP* in a concentration-dependent manner, with complete inhibition of FITC-UAP56-NTE1-19 binding observed at an RNA concentration of 1.4 μM (Fig. 4C). The mutually exclusive binding of UAP56-NTE1-19 and RNA to NP* also suggests that UAP56 acts, at least initially, on RNA-free NP during NP-mediated viral genome encapsulation.

Discussion

NP-mediated influenza virus genome packaging is driven by both NP-RNA and NP-NP interactions [4, 6, 8]. Here, we provide new insights into the mechanism by which the cellular factor UAP56 facilitates NP-RNA interaction. Our biochemical analysis of the NP-UAP56 interaction revealed a previously unknown binding site. UAP56, through the N-terminal extension, binds to the basic groove of NP between the head and body domains. In addition, the UAP56 core comprised of two RecA domains features another binding site for NP, whose binding mode remains elusive. Intriguingly, we found that binding of UAP56-NTE and RNA to NP is mutually exclusive. This observation provides molecular insights into why UAP56 facilitates NP-RNA interaction but does not associate with the NP•RNA complex [12, 21]. Our results suggest that UAP56 primes NP for engaging with viral RNA through interactions with both the NTE and the core during influenza A virus genome replication (Fig. 4D).

The mechanism of action of UAP56 here bears analogy to that in mRNA nuclear export. Like viral RNA, host mRNA is co-transcriptionally coated with a large number of proteins to form messenger ribonucleoprotein complexes (mRNPs) [27]. UAP56 is thought to facilitate the assembly of export-competent mRNPs [18–20]. In particular, UAP56 mediates recruitment of export factors including the RNA binding protein REF onto mRNPs [28, 29]. REF in turn recruits the NXF1•NXT1 complex, which is the principal receptor mediating the docking and translocation of mRNPs through the nuclear pore complex [30–32]. In its enzymatically active state, UAP56 clamps onto RNA via both RecA domains, and brings REF into the proximity of RNA [29]. Upon ATP hydrolysis, UAP56 hands over RNA to REF and leaves the mRNP in the nucleus. Although there is no evidence thus far to show the requirement of the ATPase activity of UAP56 in NP-mediated viral genome encapsulation, it is tempting to speculate that UAP56 acts in a similar manner to promote viral RNP packaging. There could be a transient state in which UAP56 is engaged with viral RNA through the core and align NP with RNA in a preferred configuration, where upon ATP hydrolysis, RNA is subsequently released from UAP56 and transferred to NP.

It is interesting to note that influenza A virus exploits the host mRNA nuclear export pathway in multiple ways [33, 34]. This is likely due to the fact that influenza A virus replicates in the cell nucleus and thus has evolved mechanisms to promote viral RNA packaging and nuclear export, and to inhibit host RNA biogenesis pathways. For example, we recently showed that influenza A virus NS1 protein targets the export receptor NXF1•NXT1 to block nuclear export of host mRNA, which causes potent blockage of host gene expression and contributes to inhibition of host immunity [35, 36]. Here we provide molecular basis for the role of UAP56 in facilitating NP-mediated viral genome packaging, which is critical for the virus life cycle. Further work is required to pinpoint the UAP56 mediated reactions involved in NP-RNA interaction. Such studies on host-pathogen interaction will provide novel mechanistic insights into the molecular pathogenesis of influenza virus infection.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Cellular factor UAP56 features multiple binding sites for influenza A virus NP.

N-terminal extension (NTE) of UAP56 recognizes nucleic acid binding site of NP.

Binding of UAP56-NTE and RNA to NP is mutually exclusive.

Acknowledgements

We thank Beatriz Fontoura for reagents and discussions on this work. We also thank the Vanderbilt Proteomics Core facility for support of the XL-MS studies. This work was supported by the National Institute of Health R35 GM133743, and funds from Vanderbilt University School of Medicine.

Please note that all Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications authors are required to report the following potential conflicts of interest with each submission. If applicable to your manuscript, please provide the necessary declaration in the box above.

(1) All third-party financial support for the work in the submitted manuscript.

(2) All financial relationships with any entities that could be viewed as relevant to the general area of the submitted manuscript.

(3) All sources of revenue with relevance to the submitted work who made payments to you, or to your institution on your behalf, in the 36 months prior to submission.

(4) Any other interactions with the sponsor of outside of the submitted work should also be reported. (5) Any relevant patents or copyrights (planned, pending, or issued).

(6) Any other relationships or affiliations that may be perceived by readers to have influenced, or give the appearance of potentially influencing, what you wrote in the submitted work. As a general guideline, it is usually better to disclose a relationship than not.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- [1].Bailey ES, Choi JY, Fieldhouse JK, Borkenhagen LK, Zemke J, Zhang DM, Gray GC, The continual threat of influenza virus infections at the human-animal interface What is new from a one health perspective?, Evol Med Public Hlth, (2018) 192–198. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [2].Medina RA, 1918 influenza virus: 100 years on, are we prepared against the next influenza pandemic?, Nat Rev Microbiol, 16 (2018) 61–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [3].Giese S, Bolte H, Schwemmle M, The Feat of Packaging Eight Unique Genome Segments, Viruses, 8 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [4].Hutchinson EC, von Kirchbach JC, Gog JR, Digard P, Genome packaging in influenza A virus, J Gen Virol, 91 (2010) 313–328. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [5].Eisfeld AJ, Neumann G, Kawaoka Y, At the centre: influenza A virus ribonucleoproteins, Nat Rev Microbiol, 13 (2015) 28–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [6].Arranz R, Coloma R, Chichon FJ, Conesa JJ, Carrascosa JL, Valpuesta JM, Ortin J, Martin-Benito J, The Structure of Native Influenza Virion Ribonucleoproteins, Science, 338 (2012) 1634–1637. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [7].te Velthuis AJW, Fodor E, Influenza virus RNA polymerase: insights into the mechanisms of viral RNA synthesis, Nat Rev Microbiol, 14 (2016) 479–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [8].Ye QZ, Krug RM, Tao YZJ, The mechanism by which influenza A virus nucleoprotein forms oligomers and binds RNA, Nature, 444 (2006) 1078–1082. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [9].Turrell L, Lyall JW, Tiley LS, Fodor E, Vreede FT, The role and assembly mechanism of nucleoprotein in influenza A virus ribonucleoprotein complexes, Nat Commun, 4 (2013). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [10].Biswas SK, Boutz PL, Nayak DP, Influenza virus nucleoprotein interacts with influenza virus polymerase proteins, Journal of Virology, 72 (1998) 5493–5501. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [11].O’Neill RE, Palese P, NPI-1, the human homolog of SRP-1, interacts with influenza virus nucleoprotein, Virology, 206 (1995) 116–125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [12].Momose F, Basler CF, O’Neill RE, Iwamatsu A, Palese P, Nagata K, Cellular splicing factor RAF-2p48/NPI-5/BAT1/UAP56 interacts with the influenza virus nucleoprotein and enhances viral RNA synthesis, J Virol, 75 (2001) 1899–1908. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [13].Kawaguchi A, Momose F, Nagata K, Replication-Coupled and Host Factor-Mediated Encapsidation of the Influenza Virus Genome by Viral Nucleoprotein, Journal of Virology, 85 (2011) 6197–6204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [14].Linder P, Jankowsky E, From unwinding to clamping - the DEAD box RNA helicase family, Nat Rev Mol Cell Bio, 12 (2011) 505–516. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [15].Fleckner J, Zhang M, Valcarcel J, Green MR, U2AF65 recruits a novel human DEAD box protein required for the U2 snRNP-branchpoint interaction, Genes Dev, 11 (1997) 1864–1872. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [16].Luo MJ, Zhou ZL, Magni K, Christoforides C, Rappsilber J, Mann M, Reed R, Pre-mRNA splicing and mRNA export linked by direct interactions between UAP56 and Aly, Nature, 413 (2001) 644–647. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [17].Zhang F, Wang J, Xu J, Zhang Z, Koppetsch BS, Schultz N, Vreven T, Meignin C, Davis I, Zamore PD, Weng Z, Theurkauf WE, UAP56 couples piRNA clusters to the perinuclear transposon silencing machinery, Cell, 151 (2012) 871–884. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [18].Carmody SR, Wente SR, mRNA nuclear export at a glance, J Cell Sci, 122 (2009) 1933–1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [19].Xie Y, Ren Y, Mechanisms of nuclear mRNA export: A structural perspective, Traffic, 20 (2019) 829–840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [20].Stewart M, Nuclear export of mRNA, Trends Biochem Sci, 35 (2010) 609–617. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [21].Hu Y, Gor V, Morikawa K, Nagata K, Kawaguchi A, Cellular splicing factor UAP56 stimulates trimeric NP formation for assembly of functional influenza viral ribonucleoprotein complexes, Sci Rep, 7 (2017) 14053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [22].Shi H, Cordin O, Minder CM, Linder P, Xu RM, Crystal structure of the human ATP-dependent splicing and export factor UAP56, P Natl Acad Sci USA, 101 (2004) 17628–17633. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [23].Ng AK, Zhang H, Tan K, Li Z, Liu JH, Chan PK, Li SM, Chan WY, Au SW, Joachimiak A, Walz T, Wang JH, Shaw PC, Structure of the influenza virus A H5N1 nucleoprotein: implications for RNA binding, oligomerization, and vaccine design, FASEB J, 22 (2008) 3638–3647. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [24].Gotze M, Pettelkau J, Schaks S, Bosse K, Ihling CH, Krauth F, Fritzsche R, Kuhn U, Sinz A, StavroX-A Software for Analyzing Crosslinked Products in Protein Interaction Studies, J Am Soc Mass Spectr, 23 (2012) 76–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [25].Ng AKL, Wang JH, Shaw PC, Structure and sequence analysis of influenza A virus nucleoprotein, Sci China Ser C, 52 (2009) 439–449. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [26].Baudin F, Bach C, Cusack S, Ruigrok RWH, Structure of Influenza-Virus Rnp .1. Influenza-Virus Nucleoprotein Melts Secondary Structure in Panhandle Rna and Exposes the Bases to the Solvent, Embo J, 13 (1994) 3158–3165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [27].Singh G, Pratt G, Yeo GW, Moore MJ, The Clothes Make the mRNA: Past and Present Trends in mRNP Fashion, Annu Rev Biochem, 84 (2015) 325–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [28].Taniguchi I, Ohno M, ATP-dependent recruitment of export factor Aly/REF onto intronless mRNAs by RNA helicase UAP56, Mol Cell Biol, 28 (2008) 601–608. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [29].Ren Y, Schmiege P, Blobel G, Structural and biochemical analyses of the DEAD-box ATPase Sub2 in association with THO or Yra1, Elife, 6 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [30].Gruter P, Tabernero C, von Kobbe C, Schmitt C, Saavedra C, Bachi A, Wilm M, Felber BK, Izaurralde E, TAP, the human homolog of Mex67p, mediates CTE-dependent RNA export from the nucleus, Mol Cell, 1 (1998) 649–659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [31].Fribourg S, Braun IC, Izaurralde E, Conti E, Structural basis for the recognition of a nucleoporin FG repeat by the NTF2-like domain of the TAP/p15 mRNA nuclear export factor, Mol Cell, 8 (2001) 645–656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [32].Grant RP, Neuhaus D, Stewart M, Structural basis for the interaction between the Tap/NXF1 UBA domain and FG nucleoporins at 1 angstrom resolution, J Mol Biol, 326 (2003) 849–858. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [33].Kuss SK, Mata MA, Zhang L, Fontoura BM, Nuclear imprisonment: viral strategies to arrest host mRNA nuclear export, Viruses, 5 (2013) 1824–1849. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [34].York A, Fodor E, Biogenesis, assembly, and export of viral messenger ribonucleoproteins in the influenza A virus infected cell, Rna Biol, 10 (2013) 1274–1282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [35].Zhang K, Xie Y, Munoz-Moreno R, Wang J, Zhang L, Esparza M, Garcia-Sastre A, Fontoura BMA, Ren Y, Structural basis for influenza virus NS1 protein block of mRNA nuclear export, Nat Microbiol, 4 (2019) 1671–1679. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [36].Satterly N, Tsai PL, van Deursen J, Nussenzveig DR, Wang Y, Faria PA, Levay A, Levy DE, Fontoura BM, Influenza virus targets the mRNA export machinery and the nuclear pore complex, Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A, 104 (2007) 1853–1858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- [37].Schrodinger LLC, The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.8, 2015. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.