Visual Abstract

Keywords: Caregivers; Developed Countries; Hemodialysis, Home; peritoneal dialysis; Qualitative Research; Narration; Patient Reported Outcome Measures; Cognition

Abstract

Background and objectives

Compared with hemodialysis, home peritoneal dialysis alleviates the burden of travel, facilitates independence, and is less costly. Physical, cognitive, or psychosocial factors may preclude peritoneal dialysis in otherwise eligible patients. Assisted peritoneal dialysis, where trained personnel assist with home peritoneal dialysis, may be an option, but the optimal model is unknown. The objective of this work is to characterize existing assisted peritoneal dialysis models and synthesize clinical outcomes.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

A systematic review of MEDLINE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trails, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Embase, PsycINFO, and CINAHL was conducted (search dates: January 1995–September 2018). A focused gray literature search was also completed, limited to developed nations. Included studies focused on home-based assisted peritoneal dialysis; studies with the assist provided exclusively by unpaid family caregivers were excluded. All outcomes were narratively synthesized; quantitative outcomes were graphically depicted.

Results

We included 34 studies, totaling 46,597 patients, with assisted peritoneal dialysis programs identified in 20 jurisdictions. Two categories emerged for models of assisted peritoneal dialysis on the basis of type of assistance: health care and non–health care professional assistance. Reported outcomes were heterogeneous, ranging from patient-level outcomes of survival, to resource use and transfer to hemodialysis; however, the comparative effect of assisted peritoneal dialysis was unclear. In two qualitative studies examining the patient experience, the maintenance of independence was identified as an important theme.

Conclusions

Reported outcomes and quality were heterogeneous, and relative efficacy of assisted peritoneal dialysis could not be determined from included studies. Although the patient voice was under-represented, suggestions to improve assisted peritoneal dialysis included using a person-centered model of care, ensuring continuity of nurses providing the peritoneal dialysis assist, and measures to support patient independence. Although attractive elements of assisted peritoneal dialysis are identified, further evidence is needed to connect assisted peritoneal dialysis outcomes with programmatic features and their associated funding models.

Introduction

The number of patients on KRT exceeds 2 million worldwide, and in many countries, the need for these services greatly outweighs provision (1). In-center hemodialysis (HD) is the most common type of dialysis therapy initiated for patients with ESKD in developed nations (1). Peritoneal dialysis (PD) achieves similar clinical outcomes to in-center HD in eligible patients (2), however, the selection of dialysis modality can depend on many factors beyond clinical effectiveness. As a home-based therapy, PD alleviates the significant burden and fatigue of travel to and from the hospital or dialysis unit for patients (3). From a health care system perspective, providing HD is often more costly than PD, because of added human and/or infrastructural resource requirements (3,4).

In many settings, efforts are being made to increase the proportion of patients receiving PD, at least in part owing to the reduced cost relative to HD (1–3). Some patients eligible for PD may face barriers to use of this dialysis modality, such as physical, cognitive, or psychosocial factors preventing in-home performance of PD. If these barriers cannot be overcome, these patients are likely to receive in-center HD. The provision of formal external assistance may increase the utilization of PD among eligible patients (4).

Assisted PD is the provision of assistance for the PD procedure by individuals in the patient’s home, and may be offered to individuals unable to perform PD (4). The type of assistance offered can vary in terms of breadth and frequency of assistance and may evolve over time with patient needs (4). As dialysis programs struggle with increasing demand, resource constraints, and evolving patient needs and preferences, assisted PD is an option to complement existing dialysis provision. However, there is no comprehensive synthesis of clinical outcomes, complications, and risks of assisted PD. The objective of this work is to systematically characterize existing assisted PD models and synthesize outcomes.

Materials and Methods

A systematic review was conducted, guided by Joanna Briggs Institute methodology (5) and Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses reporting standards (6). To capture the literature characterizing assisted PD models internationally, the gray literature was searched extensively.

Search Strategy

MEDLINE, Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trails, Cochrane Database of Systematic Reviews, Embase, PsycINFO, and CINAHL were searched from January 1995 to September 26, 2018. The search strategy was developed in consultation with an expert medical librarian. Search terms combined controlled language and text words for PD with words for assistance (full MEDLINE search strategy in Supplemental Appendix 1). The date limit was applied to identify only modern implementations of assisted PD. Animal studies, infant or child studies, comments, editorials, letters, and review articles were excluded.

Gray literature searches were guided by the “Grey Matters” tool (7). Websites of relevant organizations (e.g., kidney care organizations) were also searched (Supplemental Appendix 2). On the basis of a previous health technology assessment of dialysis modalities, a targeted scan of international jurisdictions was completed, focusing on: Canada, Australia, the United Kingdom (UK), the United States (Medicare and Medicaid programs), France, Belgium, Denmark, Spain, Switzerland, Germany, The Netherlands, Italy, and Brazil (8).

Study Selection

Titles and abstracts, and full texts were screened independently in duplicate. Abstracts included by either reviewer proceeded to full-text review. At full-text screening, disagreement was resolved through discussion. Records were included if the following criteria were met: reported original data in a peer-reviewed publication; designed as a randomized, controlled trial, quasi-experimental or implementation study, observational cohort study, survey, qualitative description (e.g., interviews, focus groups), or case study of implementation experiences; focused on home-based assisted PD (as identified by the study); published in English or French; and reported outcomes related to evaluation, characterization, patient eligibility, and implementation/delivery considerations of assisted PD models, or any patient-reported outcomes related to preferences, experience, barriers, and facilitators. Published conference abstracts were considered as full texts for inclusion. Records with only a title available were excluded. Dialysis modalities other than assisted PD, or assisted PD provided outside the home, or exclusively provided by unpaid family caregivers, were excluded.

Data from included published studies were extracted independently in duplicate using standardized data extraction forms. The following data were extracted: publication date, study design, jurisdiction or country, inception date of assisted PD program, type of PD technology (automated PD or continuous ambulatory PD), targeted and/or eligible patients, type of individual providing the assistance (e.g., registered nurse, nurse assistant or health care aid, home assistant), scope of PD assistance, frequency of assistance, description of training, implementation requirements, comparator groups (if relevant), follow-up, and main study outcomes (with any summary measure). Given the variety of definitions for the type of professional providing assistance, we applied the below definitions:

Registered nurses: self-regulated health care professionals that work autonomously and in collaboration to achieve optimal levels of health, at all stages of life, and in situations of health, illness, injury, and disability (9). Registered nurses deliver direct health care services, coordinate care, and support clients to manage their own health (9).

Licensed practical nurses: self-regulated health care professionals that work independently or in collaboration with other members of a health care team to assess, plan, implement, and evaluate care for patients (9).

Health care aides: unregulated health care workers that provide daily living support to clients, through assistance in feeding, mobility, exercise, bathing, grooming, dressing, toileting, and personal hygiene activities (10).

Because of variation in reporting in gray literature, limited data were extracted: name of jurisdiction/country, patient population, type and scope of assistance, program details, and implementation considerations.

Statistical Analyses

Included studies were synthesized by type of assisted PD. All outcomes were narratively synthesized; quantitative outcomes in studies with a comparator were graphically depicted. Study quality was assessed with the Methodological Index for Non-Randomized Studies tool, the Critical Appraisal Skills Program Qualitative Checklist, or the Consensus Health Economic Criteria (11–13).

Results

Included Published and Gray Literature

A total of 1982 unique citations were identified (Figure 1). Of these, 78 proceeded to full-text review. One publication was identified through gray literature (14,15); gray literature documents were also identified for two programs documented in published literature (16–18). Assisted PD programs were identified in 20 unique jurisdictions, with 15 follow-up evaluations of those models (Table 1) (19–33). The final data set included 34 studies and a total of 46,597 patients (Supplemental Appendix 3).

Figure 1.

Flowchart of included published and gray literature assisted peritoneal dialysis (PD) models. Thirty-four studies were included.

Table 1.

Overview of assisted PD models identified from the published and gray literature

| Assisted PD Model | Type of Assistant | Frequency of Assistance | Jurisdiction | Targeted or Eligible Patients with ESKD | Assisted PD Model Features |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Health care professional assistance | Registered nurse | 1–4 visits per day | Australia (Western) (34) | • Patients with a working PD catheter, willingness to consent, reasonable house condition, and a phone | • Assistance provided for automated PD |

| Shorter duration of visit (<1 hr) with increasing frequency of visits | • Patient, family, or other individual providing assistance (e.g., paid home assistant) required to perform connections and disconnections, important in case of alarms or emergency | • Survey of current patients on PD or HD was conducted in one center to determine potential uptake of assisted PD | |||

| • Assistance provided to patients requiring immediate dialysis awaiting self-care training (i.e., short term), for existing patients on dialysis who would otherwise be hospitalized, and respite care from family-assisted PD | |||||

| • Coordinated through existing ‘Home Link’ nursing services in one hospital | |||||

| • A “one visit per day” policy was established for the program because of funding restrictions | |||||

| Belgium (22) | NR | • Assistance provided for automated PD and continuous ambulatory PD | |||

| • Transportation and (re)training are not considered in scope of paid assistance | |||||

| Denmark (28,35) | • Frail, mainly elderly, patients characterized by loss of physical independence | • Assistance provided for automated PD | |||

| • Sole inclusion criterion was physical dependency on another individual or caregiver to set up and possibly connect and disconnect PD machine | • Coordinated (training and support) provided by dedicated PD nurses in outpatient clinic | ||||

| France (19–21,23–25,30,31,36) | • Adult patients who were unable to perform their PD exchanges alone | • Assistance provided for automated PD and continuous ambulatory PD | |||

| • Evaluation of a patient’s ability to perform PD exchanges was on the basis of subjective assessment by physician and PD nurses | • Established network of privately paid nurses across the country, trained and available to assist with at-home PD | ||||

| • Publicly paid PD nurses (in hospital) perform home visits, conduct training, and coordinate assistance of private nurses | |||||

| • Private nurses tend to be located near the patient’s home | |||||

| • Supplementary assistance provided by family members when available | |||||

| Germany (37) | NR | • Assistance provided for automated PD and continuous ambulatory PD | |||

| New York, USA (38) | • Elderly and disabled patients with multiple medical and social problems | • Assistance provided for automated PD and continuous ambulatory PD | |||

| • Longer-term and short-term (owing to acute deterioration of patient or partner resulting in inability to perform PD) assistance offered | |||||

| • Coordinated with a nursing agency to identify and train nurses | |||||

| Ontario, Canada (18,26,27,29,39–41) | • Patients with at least one medical or social condition that could be a barrier to PD | • Assistance provided for automated PD and continuous ambulatory PD | |||

| • For Toronto program (Sunnybrook Health Sciences Centre): patients required to live in area of home care support; and patients, family, or other individual had to be able to perform disconnection from cycler in the event of an emergency (i.e., a fire in the home) | • Assistance available for both long-stay and short-stay, including respite, patients on assisted PD | ||||

| • Partnered with community-based nursing agency that trained nurses | |||||

| • Multidisciplinary patient assessment by physician, nurse, and social worker | |||||

| • Dedicated case manager or program coordinator for regional programs | |||||

| • Assisted PD provided through two delivery models: local health integration networks with other home care services, and hospital regional nephrology programs as part of integrated dialysis care models | |||||

| Spain (22) | NR | • Assistance provided for automated PD and continuous ambulatory PD | |||

| • Program only available (and reimbursed) in the autonomous region of the Canary Islands | |||||

| Sweden (53) | NR | • Assistance provided for automated PD and continuous ambulatory PD | |||

| • Supplementary assistance from family provided when necessary (e.g., initiating fluid exchange if nurse was late) | |||||

| Switzerland (22) | NR | • Nurses employed through organization (Spitex) that is decentralized at the level of cantons and communities | |||

| Licensed practical nurse | 2 visits per day | Manitoba, Canada (14,15) | • Patients with suitable abdomen wanting PD, but unable to manage physical and/or mental tasks associated with procedure | • Program only available in one urban area (Winnipeg) | |

| • Respite care also available for patients (or their caregivers) who are recovering from other issues | |||||

| Nurse assistant or other health care aide | 1–2 visits per day | British Columbia, Canada (16,17,32,44) | • Adult patients who choose PD, but upon completion of hospital-based PD training, are unable to independently perform PD-related tasks and/or have inadequate support to do so | • Assistance provided for automated PD | |

| • Patients must meet specific physical, cognitive psychologic, and social eligibility criteria for either short-term or long-term assistance (see Supplemental Appendix 3) | • Long-term and short-term (including respite care) assistance programs available | ||||

| • Patient, family, or other individual required to perform connection and disconnection from the machine and associated troubleshooting of potential complications | • Multidisciplinary patient assessment by physician, PD nurse, PD social worker and, when appropriate, occupational therapist | ||||

| • Trained assistants provided by contracted service provider (Nurse Next Door) and were not required to have clinical or health care certification | |||||

| Brazil (42) | • Elderly or disabled patients who had a physical dependency and/or were living by themselves, lacked the ability to perform their own treatment, or had been undergoing HD with vascular access failure or hemodynamic instability | • Assistance provided for automated PD | |||

| • Twice a day visits only available for first 15 d, then one visit per day implemented thereafter | |||||

| • Without a second visit (in the morning), patient or family member encouraged to perform the disconnection | |||||

| United Kingdom (33,43) | • Frail and/or elderly patients, including those too frail for HD | • Assistance provided for automated PD and continuous ambulatory PD | |||

| • Patient, family, or other individual required to perform connection and disconnection from the machine | • Health care workers employed by a specialized agency or nurses employed via the local trust (Primary Care Trust) | ||||

| • Aside from Manchester program, which has an in-house program, all training provided by Baxter | |||||

| Non–health care professional assistance | Home assistant supplemented by family member(s) | No fixed visits, on the basis of needs of patients and relationship with assistant | China (46) | • Patients unable to perform bag exchanges themselves (i.e., having poor self-care ability) | • Assistance provided for automated PD and continuous ambulatory PD |

| • Home assistants and/or family members were selected according to education (health care background not required), ability to read and write, cognition, and hands-on skills | |||||

| • Training provided by nurses at dialysis clinic, but home assistant compensated by employer or patient medical insurance | |||||

| Kuwait (47) | • Patients with high motivation for PD and guaranteed family or other caregiver support | • Assistance provided for automated PD and continuous ambulatory PD | |||

| • Oversight and training provided by PD team in hospital | |||||

| Portugal (52) | • Elderly and other patients with physical or cognitive disabilities who are incapable of performing own treatment | • Assistance provided for automated PD and continuous ambulatory PD | |||

| Saudi Arabia (48) | • Elderly and other patients unable to perform PD themselves owing to comorbidities, physical disabilities, or psychosocial problems, or find it difficult to attend in-center HD | • Assistance provided for automated PD and continuous ambulatory PD | |||

| • Home assistant received training at training center and evaluated by PD nurses in-hospital | |||||

| Singapore (49) | NR | • Assistance provided for automated PD and continuous ambulatory PD | |||

| • Recruitment of home assistants, training, and home visits coordinated through in-patient PD center | |||||

| Taiwan (50,51) | • Elderly, dependent patients | • Assistance provided for automated PD and continuous ambulatory PD | |||

| • Home assistants were commonly migrant workers from neighboring South Asian countries | |||||

| • Training provided by a PD nurse assigned to each patient and monthly monitoring performed in hospital |

PD, peritoneal dialysis; HD, hemodialysis; NR, not reported.

Included studies were cohort studies (n=24), cross-sectional survey studies (n=4), quasi-experimental designs (n=3, pilot implementation trials), and one descriptive case example of an assisted PD experience. The two remaining studies used qualitative study designs. Detailed characteristics of included studies are in Supplemental Appendix 3.

Identified Models of Assisted PD

Assisted PD programs were identified in 20 unique jurisdictions, with two categories for models of assisted PD on the basis of the type of assistant or individual providing the assistance emerging: the health care professional assistance model and the non–health care professional assistance model (Table 1). Among included studies, quality was heterogeneous (Supplemental Appendix 4). No randomized, controlled trials were identified, and variation in jurisdictions for assisted PD was present.

Scope of Assistance for PD

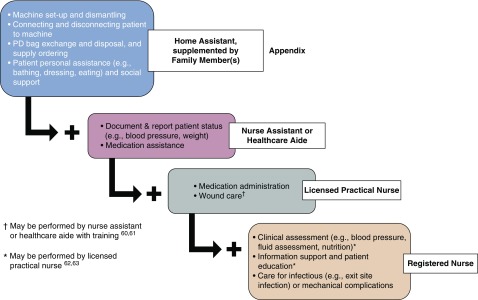

Within the health care professional assistance model, three types of individuals providing assistance were commonly described: a registered nurse (18–31,34–41), a licensed practical nurse (14,15), and a nurse assistant/health care aide (16,32,33,42–44) (Table 1).In general, there is a core set of procedural assistance that can be provided by all PD assistants in the characterized models (dark blue box, Figure 2) (45). Home assistants, with the support of patient’s family, are trained to provide the most basic assistance with the operation of the PD machine, including machine set-up and dismantling, machine connections, PD bag exchange, and ordering and disposal of PD supplies (46–52). Home assistants can also provide social support and assistance with activities of daily living (45).

Figure 2.

Scope of peritoneal dialysis (PD) assistance by type of assistant. With increased professional regulation and qualifications, more advanced clinical care tasks may be completed.

Additional support for more complex medical care of patients receiving assisted PD is permitted in health care professional assistance models (14,22,34–39,42–44,53). Nurse assistants or health care aides offer support with medication assistance to patients receiving assisted PD (42–44), and documentation of status (e.g., BP monitoring, monitoring weight) for the PD nurse and/or nephrology care team overseeing the assisted PD program (light blue box, Figure 2) (10,54). Assisted PD provided by an licensed practical nurse (14,15) increases the scope of assistance to include medication administration and wound care, although health care aides may also perform the latter (green box, Figure 2) (55,56). The broadest scope of assistance was documented with the registered nurse models of assisted PD (red box, Figure 2) (22,34–39,53). In addition to the aforementioned, assistance by registered nurse includes care for infections and/or mechanical complications, detailed clinical assessments, and patient education (57,58). The main difference between licensed practical nurse and registered nurse support is the registered nurse’s ability to care for more serious adverse events (57,58).

Health Care Professional Assistance Models

Use of registered nurses for assisted PD was identified in six European countries, including France (19–21,23–25,30,31,36), Belgium (22), Denmark (28,35), Germany (37), Sweden (53), and Switzerland (22), as well as specific regions in Spain (Canary Islands) (22), Australia (Western region) (34), the United States (Stony Brook, NY) (38), and Canada (Toronto, Ontario) (18,26,27,29,39–41). The number of visits made by registered nurses to assist patients receiving PD at home varied across jurisdictions and ranged from one to four times a day, with visit duration inversely related to number of visits. All jurisdictions described assistance for the automated PD procedure, whereas assistance for both automated PD and continuous ambulatory PD was described in seven jurisdictions (22,36–39,53). Use of registered nurse assistance for long-term patients on assisted PD was commonly described. However, short-term assisted PD and respite care was also documented in three jurisdictions (34,38,39).

Use of licensed practical nurses was documented only in Winnipeg, Canada (14,15). In this model, licensed practical nurses visited the patient home up to twice per day and provided both short-term (including respite) and long-term assistance for PD (14,15).

Lastly, assisted PD provided by nurse assistants or health care aides was identified in Brazil (42), the United Kingdom (England and Northern Ireland) (33,43), and one Canadian province (British Columbia [BC]) (16,17,32,44). Generally, nurse assistants or health care aides visited patients’ homes once or twice daily to provide PD assistance. In Brazil, twice-daily visits occurred within the first 15 days after a patient begins automated assisted PD and once a day thereafter. All jurisdictions encouraged additional assistance from family member(s) for the PD procedure. In both the United Kingdom and BC models, nurse assistants or health care aides were employed by contract agencies or service providers for both automated PD and continuous ambulatory PD (16,17,32,33,43,44). Further, both long-term and short-term (including respite) assisted PD was documented in only the BC assisted PD model (16,17,32,44).

Non–Health Care Professional Assistance Models

In this assisted PD model, assistance is provided by a home assistant, such as a domestic worker who is not a licensed health care professional, with no prior training in health care. This model was identified in six jurisdictions: China (46), Kuwait (47), Saudi Arabia (48), Singapore (49), Taiwan (50,51), and Portugal (52). Typically, home assistants received assisted PD training through in-hospital programs or dialysis clinics (46–51). In all jurisdictions, patients’ family members or informal caregivers also provide supplemental assistance for PD, and so undergo the same assisted PD training as home assistants. Given this coordinated support, there are no fixed number of visits described for this assisted PD model. Assistance for both the automated PD and continuous ambulatory PD procedures were also provided (46–52).

Patient Eligibility

The most common requirement or characteristic described for patients to receive assisted PD is the inability to autonomously perform the PD procedure in their home because of either physical, cognitive, and/or psychosocial barriers (14,35,36,39,42,44,46,48,52). Across the included assisted PD models, patients were often frail and elderly individuals, or adults with physical disability (14,34–36,38,39,42–44,46,48,51,52).

In certain jurisdictions, particularly with the health care professional assistance models, additional eligibility criteria are described. For instance, in Australia (34), Ontario (39), BC (17,44), and the United Kingdom (43), the patient or a family member must be able to perform the connections and disconnections to the PD machine to be eligible for assisted PD. This enables the registered nurse or the nurse assistant to visit once per day to the patient’s home, and is described as insurance against emergencies or machine malfunctions that may occur outside of the assisted PD visit (34,39,44). The BC assisted PD program also has distinct eligibility criteria on the basis of defined physical, cognitive, psychologic, and social factors: health status prevents dismantling/setting up the cycler; dexterity/strength/vision deficits limit the ability of the client to complete necessary tasks; cognitive function or learning deficits (such as memory, problem solving, or decision making) affect the client’s ability to safely complete necessary tasks; confidence to perform necessary tasks independently is absent; and absent or intermittent availability of support person(s) after identification that such support to manage PD is needed (59).

Patient- and System-Level Outcomes

Eighteen of the included studies examined the impacts of an assisted PD model on a patient- and/or system-level outcome, relative to a comparator (19–21,23,25–28,30,33,39,44,46,48–52). Figure 3 summarizes the effect of assisted PD relative to self-care PD (19–21,23,25,28,30,46,48–52), no assisted PD (27,44), in-center HD (26,33), family-assisted PD (19–21,23,25,30), private caregiver–assisted PD (51), or other dialysis modalities (39) on 14 reported outcomes. Each shape on the graph represents results from an individual study, with the type of assisted PD model indicated by the different shapes. Color represents the comparator, and size of the shape represents sample size for the assisted PD group. Studies that reported a relative increase in the reported outcome are plotted in the top third of the graph, whereas studies that reported no difference between assisted PD and the comparator group or a relative decrease are plotted in the middle and bottom third of the graph, respectively. Length of the study follow-up is also represented by the vertical position of the circle within each of the three strata.

Figure 3.

Outcomes from studies comparing assisted peritoneal dialysis (PD) with a comparator. There was marked variability in findings across studies. For example, there were studies that found assisted PD increased, decreased, and resulted in no change for the outcome of peritonitis, although there was variation in the type of assistance provided, comparator, and sample size. HD, hemodialysis.

Outcomes in Figure 3 were primarily from studies evaluating the registered nurse and the nurse assistant or health care aide assisted PD models. For most outcomes, there was marked variability in findings across studies. Notable, there were studies that found assisted PD increased, decreased, and resulted in no change for the outcome of peritonitis, although there was variation in the type of assistance provided, comparator, and sample size. Other outcomes were more consistent, with no other outcome occupying all three strata for relative effect owing to assisted PD. For example, assisted PD increased or resulted in no change for the outcome of mortality, regardless of the type of assistance, comparator, or sample size. Two studies evaluated changes in overall PD use with the registered nurse assisted PD model in Ontario, and reported an increase (27) relative to no assist, or no difference relative to other dialysis modalities (39). The effect of the licensed practical nurse assisted PD model was not evaluated in any of the included studies.

Patient Experience

Two included studies evaluated the experience of patients receiving assisted PD (32,53). Petersson and Lennerling (53) applied a hermeneutic phenomenological approach to explore experiences of persons living with assisted PD in Sweden. Bevilacqua et al. (32) used semistructured interviews to identify potential values, enablers, barriers, and suggestions to improve an assisted PD program in BC. Broadly, patients valued the ability to maintain independence, the feeling of support, and the relief from burden associated with self-care PD. The phenomenon of living with assisted PD was characterized in four main themes: facing new demands, managing daily life, partnerships in care, and experiencing a meaningful life (53). Suggestions to improve assisted PD included using a person-centered model of care, ensuring continuity of nurses providing the PD assist, and providing measures to support patient independence (e.g., education, telephone support) (32,53).

Discussion

This review identified assisted PD models in 20 jurisdictions in Europe, Asia, South America, Australia, Canada, and the United States. Two categories of assisted PD models emerged: assistance from health care professionals and assistance from non–health care professionals. The most established and commonly implemented model was registered nurse assisted PD. Licensed practical nurse and nurse assistant or health care aide models are documented in more recent literature from Canada and the United Kingdom.

Most assisted PD models were delivered in large urban centers, where there is likely a high prevalence of eligible patients in a circumscribed geographic area. For eligible patients living in rural/remote settings, the same physical, cognitive, or psychosocial barriers preventing the autonomous conduct of PD likely also contribute to difficulties accessing in-center HD. The provision of assisted PD to these patients will require efforts to overcome barriers such as increased travel distance, difficulties recruiting care assistants, and lack of choice of care assistants (60). In general, differentiation of the level of assistance required by patients in included studies was not well described. And regardless of setting, there were no discernible trends in outcomes by type of assistance provided.

Although clinical outcomes with assisted PD were evaluated, heterogeneous quality, reporting, and results do not allow conclusions to be made. Further, despite it being likely that availability of assisted PD increases PD utilization, this was rarely evaluated. Available data makes it challenging to assess to what extent provision of assisted PD increased the proportion of patients on assisted PD, and correlation of PD utilization with programmatic features. This outcome is expected to depend on jurisdiction specific features also, such as the funding model.

Giuliani et al. (4) cautions that although assisted PD may be an alternative for dependent patients that would otherwise receive in-center HD, many factors besides clinical indications may influence the distribution of dialysis modalities. Themes associated with assisted PD of facing new demands, managing daily life, partnerships in care, and experiencing a meaningful life complement findings that patients receiving assisted PD value the maintenance of independence, the feeling of support, and relief from burden associated with self-care (32,53). The success of assisted PD programs is likely influenced by the ability to meet these needs, although they are rarely used as metrics for evaluation. This review supports findings by Giuliani et al. (4) that assisted PD should be intended to expand modality choices and enhance patient centricity.

In a review of PD first or favored policies, Liu et al. (61) suggests that an important component of PD first policies is the objective evaluation of patient outcomes after implementation. Although many objective outcomes are frequently measured, it is unclear if patients do worse, the same, or better with assisted PD than the appropriate comparator. Further, the effect of assisted PD on PD utilization rates is rarely reported. Our recommendation is more focused than that of Liu et al. (61): if the goal of PD-favoring programs, such as assisted PD, is to increase PD utilization, this outcome should be explicitly reported in evaluations of assisted PD.

Although searches of published and gray literature were extensive, this systematic review was limited to evidence in either English or French. Pooled analysis of reported outcome measures was not feasible because of heterogeneity in comparators and point estimates/measures of association. In commonly reported outcomes (e.g., transfer to HD, peritonitis, mortality, etc.), there was marked variability reported for all model types. No protocol for this systematic review was registered. And on the Equator Network website, there was no suitable tool for the quality assessment of the study by Dratwa (22,62). Although the Consensus on Health Economic Criteria was used, many items were not relevant to this study.

Many studies were identified characterizing and evaluating assisted PD; however, the evidence was limited. Relative effectiveness could not be determined from available studies. No randomized, controlled trials were identified, which limits validity of reported outcomes, and the patient voice was under-represented. Further evidence is needed to connect assisted PD outcomes with programmatic features and their associated funding models.

Disclosures

Dr. Klarenbach reports a proportion of his salary is paid for by Alberta Health Services in his role as Co-Scientific Director of the Kidney Health Strategic Clinical Network. Dr. Clement, Mr. Hofmeister, Dr. Scott-Douglas, and Dr. Soril have nothing to disclose.

Funding

This report was supported by a financial contribution from Alberta Health through the Alberta Health Evidence Review Process, the Alberta model for health technology assessment and policy analysis. The views expressed herein do not necessarily represent the official policy of Alberta Health.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Because this work is a secondary analysis of already published work, ethics approval is not required.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.11951019/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Appendix 1. MEDLINE search strategy.

Supplemental Appendix 2. Search strategy of gray literature.

Supplemental Appendix 3. Characteristics of included studies from the published literature.

Supplemental Appendix 4. Quality assessment.

References

- 1.Mendelssohn DC, Wish JB: Dialysis delivery in Canada and the United States: A view from the trenches. Am J Kidney Dis 54: 954–964, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Yeates K, Zhu N, Vonesh E, Trpeski L, Blake P, Fenton S: Hemodialysis and peritoneal dialysis are associated with similar outcomes for end-stage renal disease treatment in Canada. Nephrol Dial Transplant 27: 3568–3575, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mehrotra R, Devuyst O, Davies SJ, Johnson DW: The current state of peritoneal dialysis. J Am Soc Nephrol 27: 3238–3252, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Giuliani A, Karopadi AN, Prieto-Velasco M, Manani SM, Crepaldi C, Ronco C: Worldwide experiences with assisted peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 37: 503–508, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aromataris E, Munn Z, editor: Joanna Briggs Institute Reviewer’s Manual, North Adelaide, Australia, The Joanna Briggs Institute, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 6.Moher D, Liberati A, Tetzlaff J, Altman DG; PRISMA Group: Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ 339: b2535, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health: Grey Matters: A practical tool for searching health-related grey literature, 2019. Available at: https://www.cadth.ca/resources/finding-evidence/grey-matters. Accessed September 1, 2018

- 8.Sinclair A, Cimon K, Loncar M, Sood M, Komenda P, Severn M, Klarenbach S, So H, Tsoi B, Quinn R, Pauly R, Tonelli M, Manns B, Rader T, Moulton K, Moulton K, Helis E, Crain J, Pullman D: Dialysis Modalities for the Treatment of End-Stage Kidney Disease: A Health Technology Assessment, Ottawa, ON, Canadian Agency for Drugs and Technologies in Health, 2017 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Canadian Institute for Health Information: Licensed practical nurses, 2019. Available at: https://www.cihi.ca/en/registered-nursesnurse-practitioners. Accessed September 1, 2019

- 10.Alberta Health Services: Health care aide, 2019. Available at: https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/careers/Page11729.aspx. Accessed September 1, 2019

- 11.Slim K, Nini E, Forestier D, Kwiatkowski F, Panis Y, Chipponi J: Methodological index for non-randomized studies (minors): Development and validation of a new instrument. ANZ J Surg 73: 712–716, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Critical Appraisal Skills Programme: CASP qualitative checklist, 2018. Available at: https://casp-uk.net/wp-content/uploads/2018/03/CASP-Qualitative-Checklist-2018_fillable_form.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2018

- 13.Evers S, Goossens M, de Vet H, van Tulder M, Ament A: Criteria list for assessment of methodological quality of economic evaluations: Consensus on Health Economic Criteria. Int J Technol Assess Health Care 21: 240–245, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Manitoba Renal Program: PD community care program, 2019. Available at: http://www.kidneyhealth.ca/wp/pd-community-care-program/. Accessed September 10, 2019

- 15.Manitoba Renal Program: Home dialysis: Information about peritoneal dialysis and home hemodialysis, 2016. Available at: http://www.kidneyhealth.ca/wp/wp-content/uploads/patients/HomeDialysisHandbook_web.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2019

- 16.Bevilacqua M, Hill P, Turnbull L, Er L, Chiu H: Evaluation of the PD assist pilot project: Outcomes at 12 months. BCRenal: An agency of the provincial health services authority. 2015

- 17.British Columbia Renal Agency: Best practices: Peritoneal dialysis programs, 2018. Available at: http://www.bcrenalagency.ca/resource-gallery/Documents/Best%20Practices-Peritoneal%20Dialysis%20Programs.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2019

- 18.Ontario Renal Network: 2018/19 Chronic Kidney Disease Funding Guide: Hospital and Community Funding, Toronto, ON, Ontario Renal Network, 2018 [Google Scholar]

- 19.Béchade C, Guittet L, Evans D, Verger C, Ryckelynck JP, Lobbedez T: Early failure in patients starting peritoneal dialysis: A competing risks approach. Nephrol Dial Transplant 29: 2127–2135, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Benabed A, Bechade C, Ficheux M, Verger C, Lobbedez T: Effect of assistance on peritonitis risk in diabetic patients treated by peritoneal dialysis: Report from the French Language Peritoneal Dialysis Registry. Nephrol Dial Transplant 31: 656–662, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Castrale C, Evans D, Verger C, Fabre E, Aguilera D, Ryckelynck JP, Lobbedez T: Peritoneal dialysis in elderly patients: Report from the French Peritoneal Dialysis Registry (RDPLF). Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 255–262, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Dratwa M: Costs of home assistance for peritoneal dialysis: Results of a European survey. Kidney Int Suppl 73: S72–S75, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Duquennoy S, Béchade C, Verger C, Ficheux M, Ryckelynck JP, Lobbedez T: Is peritonitis risk increased in elderly patients on peritoneal dialysis? Report from the french language peritoneal dialysis registry (rdplf). Perit Dial Int 36: 291–296, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guillouet S, Lobbedez T, Lanot A, Verger C, Ficheux M, Béchade C: Factors associated with nurse assistance among peritoneal dialysis patients: A cohort study from the French Language Peritoneal Dialysis Registry. Nephrol Dial Transplant 33: 1446–1452, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lobbedez T, Verger C, Ryckelynck JP, Fabre E, Evans D: Is assisted peritoneal dialysis associated with technique survival when competing events are considered? Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 7: 612–618, 2012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Oliver MJ, Al-Jaishi AA, Dixon SN, Perl J, Jain AK, Lavoie SD, Nash DM, Paterson JM, Lok CE, Quinn RR: Hospitalization rates for patients on assisted peritoneal dialysis compared with in-center hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1606–1614, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Oliver MJ, Garg AX, Blake PG, Johnson JF, Verrelli M, Zacharias JM, Pandeya S, Quinn RR: Impact of contraindications, barriers to self-care and support on incident peritoneal dialysis utilization. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 2737–2744, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Povlsen JV, Ivarsen P: Assisted peritoneal dialysis: Also for the late referred elderly patient. Perit Dial Int 28: 461–467, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Sunder S, Taskapan H, Jojoa J, Krishnan M, Khandelwal M, Izatt S, Chu M, Subramanian P, Chinthalapalli H, Lobbedez T, Jassal SV, Bargman JM, Oreopoulos DG: Chronic peritoneal dialysis in the tenth decade of life. Int Urol Nephrol 36: 605–609, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Verger C, Duman M, Durand PY, Veniez G, Fabre E, Ryckelynck JP: Influence of autonomy and type of home assistance on the prevention of peritonitis in assisted automated peritoneal dialysis patients. An analysis of data from the French Language Peritoneal Dialysis Registry. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 1218–1223, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verger C, Ryckelynck JP, Duman M, Veniez G, Lobbedez T, Boulanger E, Moranne O: French peritoneal dialysis registry (RDPLF): Outline and main results. Kidney Int Suppl (103): S12–S20, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Bevilacqua MU, Chiu HH, Saunders S, Turnbull L, Taylor PA, Singh RS, Salyers V: The value of patient and provider reported experiences in evaluating home-based assisted peritoneal dialysis. Eur J Pers Cent Healthc 5: 404–412, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 33.Iyasere OU, Brown EA, Johansson L, Huson L, Smee J, Maxwell AP, Farrington K, Davenport A: Quality of life and physical function in older patients on dialysis: A comparison of assisted peritoneal dialysis with hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 423–430, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fortnum D, Chakera A, Hawkins N, Vandepeer G: With a little help from my friends: Developing an assisted automated peritoneal dialysis program in Western Australia. Renal Soc Australas J 13: 83–89, 2017 [Google Scholar]

- 35.Povlsen JV, Ivarsen P: Assisted automated peritoneal dialysis (AAPD) for the functionally dependent and elderly patient. Perit Dial Int 25[Suppl 3]: S60–S63, 2005 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Lobbedez T, Moldovan R, Lecame M, Hurault de Ligny B, El Haggan W, Ryckelynck JP: Assisted peritoneal dialysis. Experience in a French renal department. Perit Dial Int 26: 671–676, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pommer W, Wagner S, Müller D, Thumfart J: Attitudes of nephrologists towards assisted home dialysis in Germany. Clin Kidney J 11: 400–405, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wadhwa NK, Suh H, Cabralda T, Sokol E, Sokunbi D, Solomon M: Peritoneal dialysis with trained home nurses in elderly and disabled end-stage renal disease patients. Adv Perit Dial 9: 130–133, 1993 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Oliver MJ, Quinn RR, Richardson EP, Kiss AJ, Lamping DL, Manns BJ: Home care assistance and the utilization of peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Int 71: 673–678, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Murray MA, Twolan C, Owens G, Ferguson C, Benard M, Verch-Whittington J: Evaluation of a new model of care to support home peritoneal dialysis patients: The nephrology integrated care demonstration project. Canadian Assoc Nephrol Nurses Tech 22: 17, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 41.Brunier G, Gray B, Coulis N, Savage J, Manuel A, McConnell H, Mildon B, Sherlock AM: The use of community nurses for home peritoneal dialysis: Is it cost-effective? Perit Dial Int 16[Suppl 1]: S479–S482, 1996 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Franco MRG, Fernandes N, Ribeiro CA, Qureshi AR, Divino-Filho JC, da Glória Lima M: A Brazilian experience in assisted automated peritoneal dialysis: A reliable and effective home care approach. Perit Dial Int 33: 252–258, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Brown N, Vardhan A: Developing an assisted automated peritoneal dialysis (aAPD) service-a single-centre experience. NDT Plus 4[Suppl 3]: iii16–iii18, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bevilacqua MU, Turnbull L, Saunders S, Er L, Chiu H, Hill P, Singh RS, Levin A, Copland MA, Jamal A, Brumby C, Dunne O, Taylor PA: Evaluation of a 12-month pilot of long-term and temporary assisted peritoneal dialysis. Perit Dial Int 37: 307–313, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Alberta Health Services: Keeping you well and independent: Home care, 2017. Available at: https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/seniors/if-sen-home-care-brochure.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2019

- 46.Xu R, Zhuo M, Yang Z, Dong J: Experiences with assisted peritoneal dialysis in China. Perit Dial Int 32: 94–101, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al-Hilali N, Nampoory MRN, Ninan TV, Ali JH, Gawish A, Johny KV: Viability of home peritoneal dialysis: Experience with 100 patients from an Arab population. Perit Dial Int 23[Suppl 2]: S165–S169, 2003 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Al Wakeel JS, Al Ghonaim MA, Aldohayan A, Usama S, Al Obaili S, Tarakji AR, Alkhowaiter M: Appraising the outcome and complications of peritoneal dialysis patients in self-care peritoneal dialysis and assisted peritoneal dialysis: A 5-year review of a single Saudi center. Saudi J Kidney Dis Transpl 29: 71–80, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Griva K, Goh CS, Kang WCA, Yu ZL, Chan MC, Wu SY, Krishnasamy T, Foo M: Quality of life and emotional distress in patients and burden in caregivers: A comparison between assisted peritoneal dialysis and self-care peritoneal dialysis. Qual Life Res 25: 373–384, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Cheng CH, Shu KH, Chuang YW, Huang ST, Chou MC, Chang HR: Clinical outcome of elderly peritoneal dialysis patients with assisted care in a single medical centre: A 25 year experience. Nephrology (Carlton) 18: 468–473, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Hsieh CY, Fang JT, Yang CW, Lai PC, Hu SA, Chen YM, Yu CC, Tian YC, Chien CC, Hung CC: The impact of type of assistance on characteristics of peritonitis in elderly peritoneal dialysis patients. Int Urol Nephrol 42: 1117–1124, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Querido S, Branco PQ, Costa E, Pereira S, Gaspar MA, Barata JD: Results in assisted peritoneal dialysis: A ten-year experience. Int J Nephrol 2015: 712539, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Petersson I, Lennerling A: Experiences of living with assisted peritoneal dialysis - a qualitative study. Perit Dial Int 37: 605–612, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Alberta Health Services: Health care aide role in medication assistance: A companion to the Alberta provincial continuing care medication assistance program (MAP) manual, 2016. Available at: https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/assets/info/seniors/if-sen-companion-to-map-hca-role-in-med-assist.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2019

- 55.Alberta Health Services: Licensed practical nurse, 2019. Available at: https://www.albertahealthservices.ca/careers/page11730.aspx. Accessed September 1, 2019

- 56.College of Licensed Practical Nurses of Alberta: LPN scope of practice explained in new fact sheet and video, 2013. Available at: https://www.clpna.com/2013/07/fact-sheet-scope-of-practice-for-lpns-in-alberta/. Accessed September 1, 2019

- 57.College and Association of Registered Nurses of Alberta: Entry-to-Practice competencies for the registered nurses profession, 2013. Available at: http://www.nurses.ab.ca/content/dam/carna/pdfs/DocumentList/Standards/RN_EntryPracticeCompetencies_May2013.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2019

- 58.College and Association of Registered Nurses of Alberta: Scope of practices for registered nurses, 2011. Available at: http://www.nurses.ab.ca/content/dam/carna/pdfs/DocumentList/Standards/RN_ScopeOfPractice_May2011.pdf. Accessed September 1, 2019

- 59.Peritoneal Dialysis Assist: Information for PD programs and nurse next door. 2017. Available at: http://www.bcrenalagency.ca/about/news-stories/news-releases/province-wide-support-program-helps-pd-patients-maintain-care-at-home. Accessed March 1, 2019

- 60.McCann S, Ryan AA, McKenna H: The challenges associated with providing community care for people with complex needs in rural areas: A qualitative investigation. Health Soc Care Community 13: 462–469, 2005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Liu FX, Gao X, Inglese G, Chuengsaman P, Pecoits-Filho R, Yu A: A global overview of the impact of peritoneal dialysis first or favored policies: An opinion. Perit Dial Int 35: 406–420, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.UK EQUATOR Centre. EQUATOR Network: Search for reporting guidelines: UK EQUATOR Centre. Available at: https://www.equator-network.org/. Accessed March, 1 2020

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.