In 2017, 21% of Canadians starting maintenance dialysis over the age of 65 received peritoneal dialysis (PD), compared with only 7% in the United States. An increasingly important reason for this difference may be the availability of assisted PD. On July 10, 2019, the Advancing American Kidney Health Initiative was announced to dramatically increase the use of home dialysis. Given this policy shift, the time is right to start assisted PD in the United States. Launching assisted PD would be greatly informed by reviewing the current state of assisted PD in Canada, outlining barriers to PD in the United States, and proposing key elements of a future pilot program (see Box 1).

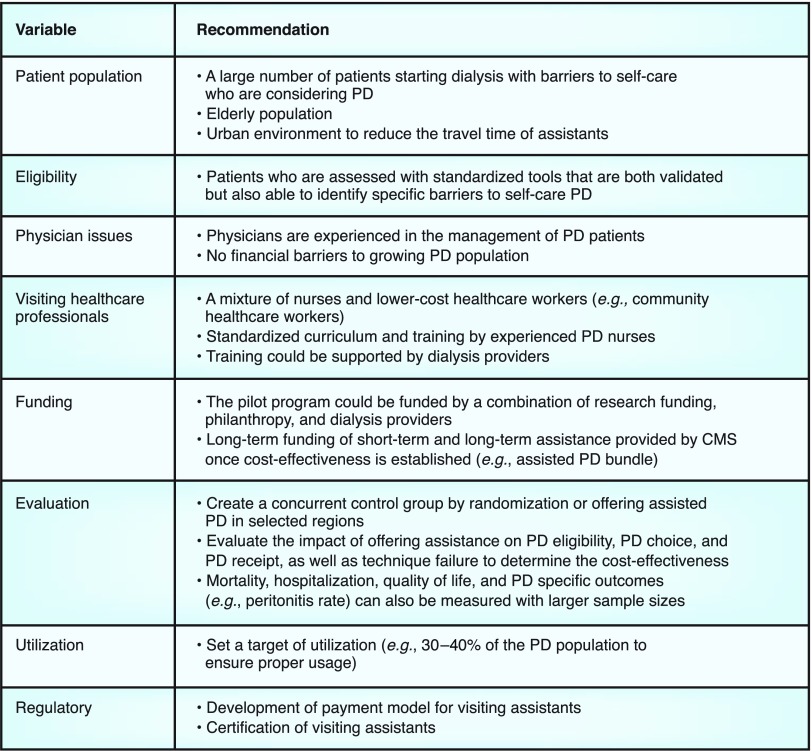

Box 1.

Recommendation for a pilot program of assisted peritoneal dialysis in the United States. PD, peritoneal dialysis; CMS, US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

Assistance benefits patients with barriers to self-care PD. Barriers may occur at any age but are more likely in older patients. For example, the mean age of patients requiring assisted PD ranges from 71 to 79 years in published reports (1,2). Physical barriers include reduced physical strength to lift PD bags, reduced dexterity to make connections, and reduced vision/hearing to respond to alarms and program the cycler (3). Cognitive barriers include dementia, learning disabilities, and active psychiatric conditions (e.g., depression, schizophrenia) (4). In 2010, 63% of patients (mean age of 66) had at least one barrier (3). In our more recent study, of the 121 patients undergoing PD training (mean age 69), functional dependency (66%), frailty (65%), and impaired cognition (59%) were common (4). Caregiver assistance ranged from 29% to 40% depending on the level of impairment. We recommend any future pilot of assisted PD in the United States should be conducted in PD programs using standard assessment tools to demonstrate barriers to self-care PD in at least 30% of patients.

Although assisted PD can be broadly defined as the need for a person—other than the patient—to provide significant assistance with PD therapy in their home, in the literature it generally refers to the use of paid caregivers. Assisted programs have existed for decades in countries such as Canada, Denmark, and France (5–8). The caregivers providing assistance range from personal support workers to registered nurses. In Canada, they are normally employed by home-care agencies (not the PD program) because the agencies have a critical mass of staff. Personal support workers assist with physical tasks such as lifting PD bags or machine set up, whereas nurses provide a broader range of help. In the United States, home-care agencies do not currently provide PD assistance. One option could be a partnership between home-care agencies and community health workers. In Minnesota, a standardized curriculum was developed which qualified these workers for reimbursement under Medicaid. We recommend a flexible model using a combination of home-care nurses for complex patients and lower-skill assistants who assist with the physical tasks of PD.

Physician engagement is also critical. In Canada, physicians are generally well trained in PD and reimbursement is equal for home dialysis and in-center hemodialysis in most provinces. In the United States, physician training and experience may be a barrier to PD growth. The monthly capitated payment system also makes it possible for physicians to be paid more for hemodialysis. Furthermore, some physicians jointly own hemodialysis units, which could be a disincentive for PD. A future assisted PD pilot should be conducted in a PD program without financial disincentives to grow PD from both a physician and provider perspective.

To facilitate assisted PD programs in the United States, a sustainable funding model will have to be developed. In British Columbia, a pilot program of assisted PD provided one visit per day by training caregivers without prior healthcare training. Patients or their families were still responsible for connections to the PD cycler. The mean cost of the visits was CA$43/d, making the cost of short-term support only CA$1250 (US$950) when provided for a median of 29 days. The cost of yearly supports was CA$15,565 (US$11,400). In Ontario, the assisted PD program provides up to two visits per day, often by home care nurses. The short-term bundle in Ontario was funded at CA$2792 (US$1904) with a median use of 50 days. The cost of the long-term program is CA$20,566 (US$15,714) with a median use of 202 days. The British Columbia pilot program also reported the cost of direct patient care was CA$383,126 (71% of the total program cost) and caregiver travel costs were CA$70,526 (13% of the total program cost). The total training and administrative costs were CA$82,814 or 16% of the total cost of the program. The British Columbia program found the long-term average costs of in-center hemodialysis would be CA$23,500 more than assisted PD, including the cost of transport back and forth to in-center hemodialysis. In the United States, it is likely a new bundled payment would have to be created to fund both short- and long-term assisted PD. Funding for a pilot program could come from dialysis providers, private philanthropy, and/or research grants; long-term funding would have to be provided by the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services.

To facilitate funding, robust evaluation is critical. We recommend creating a concurrent control group that is not offered assisted PD through randomization or offering assistance in selected programs. This control group is required to estimate the effect of assistance on PD use. We found assistance increased PD eligibility by 15% and incident PD use by 10%. The initial pilot program could also measure patient/family satisfaction and early technique survival. Other outcomes such as mortality, hospitalization, and quality of life can be compared as sample sizes increase (9,10). The utilization of the program should also be tracked. In established programs, use ranges from 39% to 43%. In a pilot program in the United States, a target usage of 30%–40% seems reasonable to balance cost while providing sufficient support to meet home dialysis targets.

There are numerous regulatory and legal hurdles involved in creating a feasibility study of assisted PD. For example, salaries of paid caregivers would require disbursement through a third party, rather than the dialysis provider. This is necessary to prevent the appearance of “inducement” and potential violation of the Stark Law. Requirements for caregiver certification will likely vary across state lines; thus the timeline for caregiver training and breadth of responsibilities permitted may differ depending on location.

In summary, assisted PD is a strategy many countries have implemented to increase home dialysis. The current shift in US policy makes now the time to launch assisted PD in the United States. Assisted PD should be offered in experienced PD programs that demonstrate objectively their patients have barriers to self-care. Consideration should be given to PD programs in states where curricula and funding models for community health or personal support workers have been developed. Funding can be provided from multiple sources initially, but ultimately the US Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services would have to fund both short- and long-term support. To develop an evaluation framework, it is critical to include a concurrent control group for evaluating the effect of assistance on PD use. Since the US Government is pushing an aggressive policy of home dialysis, it is imperative patients are provided the support they need to be successful.

Disclosures

Dr. Oliver reports receiving a grant and consulting fees from Baxter Healthcare, a grant from Medtronic, and personal fees from Pursuit Vascular, outside of the submitted work. Dr. Oliver also reports an advisory board position with Janssen Canada and that he is coinventor of the Dialysis Measurement Analysis and Reporting (DMAR) system. Dr. Salenger is Home Therapies Medical Director of Dialysis Clinic, Inc.

Acknowledgments

The author(s) acknowledge that data used in this publication were from the Ontario Renal Reporting System, collected and provided by Cancer Care Ontario and Ontario Renal Network. The content of this article does not reflect the views or opinions of the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) or CJASN. Responsibility for the information and views expressed therein lies entirely with the author(s).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Xu R, Zhuo M, Yang Z, Dong J: Experiences with assisted peritoneal dialysis in China. Perit Dial Int 32: 94–101, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lobbedez T, Moldovan R, Lecame M, Hurault de Ligny B, El Haggan W, Ryckelynck JP: Assisted peritoneal dialysis. Experience in a French renal department. Perit Dial Int 26: 671–676, 2006 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Oliver MJ, Garg AX, Blake PG, Johnson JF, Verrelli M, Zacharias JM, Pandeya S, Quinn RR: Impact of contraindications, barriers to self-care and support on incident peritoneal dialysis utilization. Nephrol Dial Transplant 25: 2737–2744, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farragher JF, Oliver MJ, Jain AK, Flanagan S, Koyle K, Jassal SV: PD assistance and relationship to co-existing geriatric syndromes in incident peritoneal dialysis therapy patients. Perit Dial Int 39: 375–381, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Oliver MJ, Quinn RR, Richardson EP, Kiss AJ, Lamping DL, Manns BJ: Home care assistance and the utilization of peritoneal dialysis. Kidney Int 71: 673–678, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Povlsen JV, Ivarsen P: Assisted peritoneal dialysis: Also for the late referred elderly patient. Perit Dial Int 28: 461–467, 2008 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Verger C, Duman M, Durand PY, Veniez G, Fabre E, Ryckelynck JP: Influence of autonomy and type of home assistance on the prevention of peritonitis in assisted automated peritoneal dialysis patients. An analysis of data from the French Language Peritoneal Dialysis Registry. Nephrol Dial Transplant 22: 1218–1223, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Béchade C, Lobbedez T, Ivarsen P, Povlsen JV: Assisted peritoneal dialysis for older people with end-stage renal disease: The French and Danish experience. Perit Dial Int 35: 663–666, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Oliver MJ, Al-Jaishi AA, Dixon SN, Perl J, Jain AK, Lavoie SD, Nash DM, Paterson JM, Lok CE, Quinn RR: Hospitalization rates for patients on assisted peritoneal dialysis compared with in-center hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 1606–1614, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iyasere OU, Brown EA, Johansson L, Huson L, Smee J, Maxwell AP, Farrington K, Davenport A: Quality of life and physical function in older patients on dialysis: A comparison of assisted peritoneal dialysis with hemodialysis. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 11: 423–430, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]