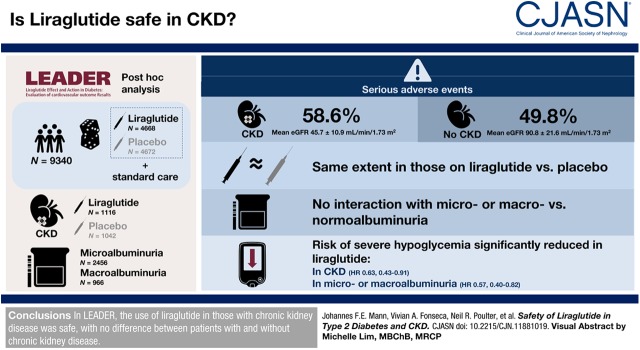

Visual Abstract

Keywords: chronic kidney disease, microalbuminuria, humans, liraglutide, type 2 diabetes mellitus, GFR, glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor, creatinine, confidence intervals, standard of care, hypoglycemia, chronic renal insufficiency, kidney, albumins

Abstract

Background and objectives

The glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonist liraglutide demonstrated cardiovascular and kidney benefits in the LEADER trial, particularly in participants with CKD.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

This post hoc analysis evaluated the safety of liraglutide treatment in patients with CKD in LEADER. Overall, 9340 patients were randomized to liraglutide or placebo, both in addition to standard of care. Of those, 2158 patients had CKD versus 7182 without CKD (defined as eGFR <60 versus ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, respectively); 966 patients had macroalbuminuria and 2456 had microalbuminuria (urine albumin-creatinine ratio >300 mg/g and ≥30 to ≤300 mg/g, respectively). At baseline, the mean eGFR in patients with CKD was 46±11 ml/min per 1.73 m2 versus 91±22 ml/min per 1.73 m2 in those without CKD. Time to first event within event groups was analyzed using Cox regression with treatment group, baseline eGFR group, or baseline albuminuria group as fixed factors.

Results

Overall, serious adverse events were more frequently recorded in patients with CKD compared with those without CKD (59% versus 50%; interaction P=0.11); however, they occurred to the same extent in those on liraglutide versus placebo. Similarly, no interaction of adverse events with randomized therapy was observed in patients with micro- or macro- versus normoalbuminuria (interaction P=0.11). Risk of severe hypoglycemia was significantly reduced with liraglutide versus placebo in patients with CKD or with micro- or macroalbuminuria (hazard ratio, 0.63 [95% CI, 0.43 to 0.91] and 0.57 [95% CI, 0.40 to 0.82], respectively).

Conclusions

In LEADER, the use of liraglutide in those with CKD was safe, with no difference between patients with and without CKD.

Clinical Trial registry name and registration number

ClinicalTrials.gov; NCT01179048 (https://clinicaltrials.gov/ct2/show/NCT01179048).

Introduction

CKD is a common complication of type 2 diabetes (1), resulting in increased morbidity and mortality (2–4). However, treatment choices to control glycemia among patients with CKD are limited. CKD is associated with failure to reach glycemic targets, despite greater use of glucose-lowering agents and prolonged insulin duration of action (1), and increased risks for both hyperglycemia and hypoglycemia (5). Additionally, the pharmacokinetic and pharmacodynamic profiles of some glucose-lowering agents are altered by CKD via various mechanisms (6). Consequently, many conventional glucose-lowering agents are unsuitable for use in patients with advanced CKD because they can cause safety issues such as increased risk of lactic acidosis (with metformin) and hypoglycemia (primarily with sulfonylureas, glinides, and insulin), thus requiring dose modifications or withdrawals (7–9). Newer type 2 diabetes therapies—such as sodium-glucose cotransporter-2 inhibitors (SGLT-2is), dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, and glucagon-like peptide-1 receptor agonists (GLP-1RAs)—have been associated with reductions in albuminuria (10–15). The GLP-1RAs liraglutide, semaglutide, and dulaglutide as well as the SGLT-2is canagliflozin, dapagliflozin, and empagliflozin have been associated with reduced progression of diabetic kidney disease based on secondary outcomes from cardiovascular outcome trials (14,16–18) and are now the recommended glucose-lowering agents, after metformin, for patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD according to the American Diabetes Association (ADA)/European Association for the Study of Diabetes consensus statement (19).

In the Liraglutide Effect and Action in Diabetes: Evaluation of cardiovascular outcome Results (LEADER) trial, liraglutide reduced major cardiovascular and kidney outcomes and all-cause mortality, compared with placebo, in patients with type 2 diabetes (20,21). The benefits were evident in those with CKD, in addition to those without CKD, at baseline (20,21).

Thus, liraglutide, approved for use in the treatment of type 2 diabetes (22), is a potentially attractive treatment for patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD. This post hoc analysis of LEADER was undertaken to assess the safety of liraglutide compared with placebo in patients with and without CKD.

Materials and Methods

Study Design, Participants, and Treatment

LEADER was a phase-3b, randomized, double-blind, multicenter, placebo-controlled cardiovascular outcome trial. Detailed methods of the trial have been published previously (21,23) as have its main results for cardiovascular and kidney outcomes (16,21). The trial included patients with type 2 diabetes at high risk of cardiovascular disease with a glycated hemoglobin (HbA1c) level of ≥7% who were treatment naive or had been treated with oral glucose-lowering agents or basal insulin (human neutral protamine Hagedorn, long-acting analogue, or premixed), alone or in combination. Major exclusion criteria were type 1 diabetes; use of GLP-1RAs, dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibitors, pramlintide, or rapid-acting insulin within 3 months before screening; and an acute coronary or cerebrovascular event in the previous 14 days before screening. After a 2-week placebo run-in phase, patients were randomly assigned (1:1) to receive either 1.8 mg (or the maximum tolerated dose) of liraglutide or matching placebo once daily as a subcutaneous injection in addition to standard care. Randomization was stratified according to the eGFR at screening (<30 or ≥30 ml/min per 1.73 m2), as calculated using the Modification of Diet in Renal Disease (MDRD) Equation (24).

A selective approach to safety data collection was used, and only events meeting the definition of a serious adverse event or medical event of special interest were systematically collected and reported (25). Medical events of special interest, both serious and nonserious, were required to be reported. These prespecified events included the following: nausea leading to treatment discontinuation, acute gallstone disease, severe hypoglycemia (defined according to ADA criteria as self-reported hypoglycemia for which the patient required assistance from another person), diabetic foot ulcer events (defined as a foot affected by ulceration associated with neuropathy and/or peripheral arterial disease of the lower limb) (26,27), and acute kidney failure (including AKI, acute prerenal failure, azotemia, toxic nephropathy, renal failure, and renal impairment). Events for acute gallstone disease, diabetic foot ulcer, and bone/joint injuries were captured for analysis using prespecified standard search terms from the Medical Dictionary for Regulatory Activities (MedDRA) version 18.0 (standard MedDRA queries) as reported by the investigator. Severe hypoglycemia was self-reported and collected from patient diaries.

Statistical Analyses

Full details of the statistical analyses have been previously described (21,23). For the purpose of this post hoc analysis, patients were grouped according to kidney status as those with CKD (defined as baseline eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 per MDRD) and those without CKD (defined as baseline eGFR ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2), or by baseline albuminuria status (micro- and macroalbuminuria defined as baseline urinary albumin-creatinine ratio [UACR] ≥30 mg/g; normoalbuminuria defined as UACR <30 mg/g). Time to first event within event groups was analyzed using Cox regression with treatment group, baseline eGFR group, or baseline albuminuria group as fixed factors. Events that occurred between the randomization date and follow-up date were used for defining first events. Patients without an event were censored at time of last contact or date of death, whichever came first. The full analysis set consisted of all of the patients who underwent randomization. No adjustment for multiplicity was performed. A P value <0.05 was considered significant.

Ethics

The trial was approved by local institutional review boards and all patients provided written informed consent. The trial was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Results

Baseline Characteristics

Overall, a total of 9340 patients comprising the full analysis set were randomly assigned to receive liraglutide (n=4668) or placebo (n=4672) in addition to standard of care. The median time of exposure to randomized treatment was 3.5 years (interquartile range [IQR], 2.5−3.9 years) with a median follow-up time of 3.8 years (IQR, 3.6−4.1 years) (21). The study population included patients with all stages of CKD, except dialysis-dependent ESKD. The study protocol mandated that 220 participants had an eGFR <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2. A total of 2158 patients had an eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (mean [SD], 46 [11]) and 7182 patients had an eGFR ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (mean [SD], 91 [22]) at baseline (defined in this analysis as patients with or without CKD, respectively). Patients with CKD were generally older, more likely to be female, had a longer duration of type 2 diabetes, were more likely to have hypertension, and had a higher baseline UACR compared with those without CKD (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics and demographics by CKD class or albuminuria status at baseline (full analysis set)

| Parameter | Patients with CKD (eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2) | Patients without CKD (eGFR ≥60 ml/min/1.73 m2) | Patients with Albuminuria (UACR ≥30 mg/g)a | Patients without Albuminuria (UACR <30 mg/g)b | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Liraglutide | Placebo | Liraglutide | Placebo | Liraglutide | Placebo | Liraglutide | Placebo | |

| N | 1116 | 1042 | 3552 | 3630 | 1684 | 1738 | 2894 | 2821 |

| Age, yr (SD) | 67 (8) | 67 (8) | 63 (7) | 64 (7) | 65 (7) | 65 (7) | 64 (7) | 64 (7) |

| Sex, male % | 62 | 61 | 65 | 65 | 68 | 68 | 63 | 62 |

| Region, N (%) | ||||||||

| Europe | 332 (30) | 326 (31) | 1307 (37) | 1331 (37) | 536 (32) | 533 (31) | 1066 (37) | 1092 (39) |

| North America | 404 (36) | 387 (37) | 997 (28) | 1059 (29) | 512 (30) | 571 (33) | 864 (30) | 832 (30) |

| Asia | 109 (10) | 69 (7) | 251 (7) | 282 (8) | 176 (11) | 162 (9) | 182 (6) | 186 (7) |

| Rest of the world | 271 (24) | 260 (25) | 997 (28) | 958 (26) | 460 (27) | 472 (27) | 782 (27) | 711 (25) |

| Race, N (%) | ||||||||

| White | 847 (76) | 786 (75) | 2769 (78) | 2836 (78) | 1242 (74) | 1269 (73) | 2306 (80) | 2266 (80) |

| Black | 77 (7) | 107 (10) | 293 (8) | 300 (8) | 142 (8) | 181 (10) | 219 (8) | 218 (8) |

| Asian | 135 (12) | 96 (9) | 336 (10) | 369 (10) | 223 (13) | 209 (12) | 244 (8) | 247 (9) |

| Other | 57 (5) | 53 (5) | 154 (4) | 125 (3) | 77 (5) | 79 (5) | 125 (4) | 90 (3) |

| eGFR, ml/min per 1.73 m2 (SD) | 46 (11) | 46 (11) | 91 (22) | 91 (22) | 74 (30) | 75 (29) | 84 (26) | 84 (26) |

| Normal (eGFR ≥90 ml/min per 1.73 m2), N (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1620 (46) | 1655 (46) | 475 (28) | 509 (29) | 1112 (38) | 1104 (39) |

| Mild impairment (eGFR 60–89 ml/min per 1.73 m2), N (%) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 1932 (54) | 1975 (54) | 626 (37) | 682 (39) | 1277 (44) | 1246 (44) |

| Moderate impairment (eGFR 30–59 ml/min per 1.73 m2), N (%) | 999 (90) | 935 (90) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 498 (30) | 464 (27) | 477 (17) | 451 (16) |

| Severe impairment (eGFR <30 ml/min per 1.73 m2), N (%) | 117 (11) | 107 (10) | 0 (0) | 0 (0) | 85 (5) | 83 (5) | 28 (1) | 20 (1) |

| Diabetes duration, yr (SD) | 15 (9) | 15 (9) | 12 (8) | 12 (8) | 14 (8) | 14 (8) | 12 (8) | 12 (8) |

| Prior stroke/MI, N (%) | 437 (39) | 424 (41) | 1566 (44) | 1567 (43) | 683 (41) | 708 (41) | 1280 (44) | 1239 (44) |

| History of MI | 325 (29) | 294 (28) | 1139 (32) | 1106 (31) | 506 (30) | 500 (29) | 935 (32) | 866 (31) |

| History of stroke | 177 (16) | 183 (18) | 553 (16) | 594 (16) | 247 (15) | 279 (16) | 463 (16) | 479 (17) |

| Hypertension, N (%) | 1067 (96) | 998 (96) | 3194 (90) | 3252 (90) | 1578 (94) | 1624 (93) | 2603 (90) | 2523 (89) |

| Body weight, kg | 91 (21) | 91 (22) | 92 (21) | 92 (20) | 91 (22) | 91 (22) | 92 (21) | 92 (20) |

| Body mass index, kg/m2 | 32 (6) | 33 (7) | 33 (6) | 32 (6) | 32 (6) | 32 (6) | 33 (6) | 33 (6) |

| HbA1c, % (SD) | 8.7 (1.6) | 8.6 (1.5) | 8.7 (1.5) | 8.7 (1.5) | 9.1 (1.7) | 8.9 (1.6) | 8.5 (1.4) | 8.5 (1.4) |

| Creatinine, mg/dl (SD)c | 1.5 (0.6) | 1.5 (0.6) | 0.8 (0.2) | 0.8 (0.2) | 1.1 (0.6) | 1.1 (0.6) | 0.9 (0.3) | 0.9 (0.3) |

| UACR, mg/g (IQR)d | 47 (229) | 52 (298) | 16 (40) | 17 (44) | 157 (303) | 163 (343) | 6 (10) | 6 (10) |

| Total cholesterol, mg/dl (SD)c | 172 (47) | 172 (47) | 172 (47) | 172 (47) | 176 (47) | 176 (51) | 172 (43) | 172 (43) |

| LDL, mg/dl)c | 90 (39) | 90 (35) | 90 (35) | 90 (35) | 94 (39) | 94 (39) | 90 (35) | 90 (35) |

| Systolic BP, mm Hg (SD) | 136 (20) | 137 (20) | 136 (17) | 136 (17) | 141 (19) | 140 (19) | 133 (17) | 134 (16) |

| Diastolic BP; mm Hg (SD) | 75 (11) | 76 (11) | 78 (10) | 77 (10) | 79 (11) | 78 (11) | 77 (10) | 77 (10) |

| Heart rate, bpm (SD) | 72 (12) | 72 (12) | 73 (11) | 73 (11) | 73 (12) | 73 (12) | 72 (11) | 72 (11) |

Data are mean (SD) or number of patients (n, proportion [%]) of patients either with eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2 or eGFR ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2. UACR, urinary albumin-creatinine ratio; MI, myocardial infarction; HbA1c, glycated hemoglobin; IQR, interquartile range.

Including macroalbuminuria (baseline UACR >300 mg/g) and microalbuminuria (baseline UACR ≥30 to ≤300 mg/g).

Including normoalbuminuria (baseline UACR <30 mg/g).

Calculated not measured.

UACR is geometric mean (IQR).

Micro- or macroalbuminuria (UACR ≥30 mg/g; defined in this analysis as albuminuria) was present in 3422 patients, whereas 5715 patients had normoalbuminuria (UACR <30 mg/g) at baseline (Table 1). Microalbuminuria was found in 2456 patients (26%) and macroalbuminuria in 966 patients (10%). The geometric mean values of UACR at baseline were 6, 78, and 997 mg/g for patients who had normo-, micro-, and macroalbuminuria, respectively.

Serious Adverse Events

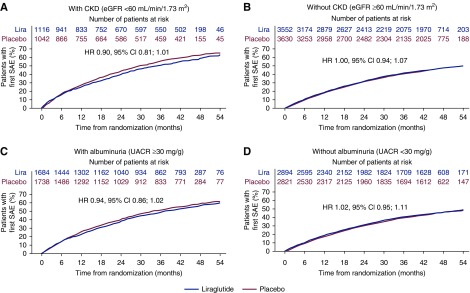

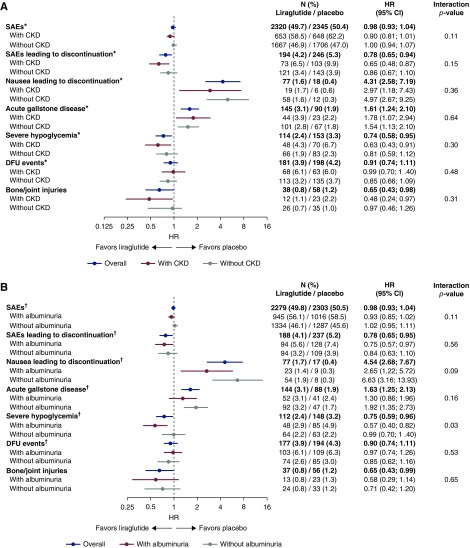

A higher proportion of patients with CKD experienced serious adverse events compared with those without CKD; however, there was no statistical difference in the number of patients experiencing serious adverse events with liraglutide versus placebo in both subgroups (Figures 1, A and B, and 2A). Significantly fewer patients with CKD treated with liraglutide versus placebo experienced serious adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation (hazard ratio [HR], 0.65; 95% CI, 0.48 to 0.87); in patients without CKD, this difference did not reach statistical significance (HR, 0.86; 95% CI, 0.67 to 1.10). There was no significant interaction between the presence or absence of CKD and the risk of serious adverse events or serious adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation according to the treatment arms (interaction P=0.11 and 0.15, respectively) (Figure 2A).

Figure 1.

Time to first serious adverse event in those with and without CKD, and with and without albuminuria at baseline. HR, hazard ratio; Lira, liraglutide; SAE, serious adverse event; UACR, urinary albumin-creatinine ratio.

Figure 2.

Treatment differences (liraglutide versus placebo) for selected adverse events by CKD class and albuminuria status at baseline. (A) Selected adverse events by CKD class at baseline. (B) Selected adverse events by albuminuria status at baseline. *All patients with eGFR at baseline; †all patients with albuminuria at baseline. Patients with CKD were defined as those with baseline eGFR <60 ml/min per 1.73 m2; patients without CKD were defined as those with baseline eGFR ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2; patients with albuminuria were defined as those with UACR ≥30 mg/g; patients without albuminuria were defined as those with UACR <30 mg/g; Diabetic foot ulcer (DFU) events included new foot ulcer events and worsening of existing foot ulcer.

A similar pattern was observed in patients with albuminuria; there was no statistical difference in the number of patients experiencing serious adverse events with liraglutide versus placebo (Figures 1, C and D, and 2B). Significantly fewer patients with albuminuria treated with liraglutide versus placebo experienced serious adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation (HR, 0.75; 95% CI, 0.57 to 0.97), but this was not statistically significant in patients without albuminuria (HR, 0.84; 95% CI, 0.63 to 1.10). There was no significant interaction between treatment and presence or absence of albuminuria for serious adverse events or serious adverse events leading to treatment discontinuation (interaction P=0.11 and 0.56, respectively) (Figure 2A).

Medical Events of Special Interest

Nausea leading to treatment discontinuation and acute gallstone disease were experienced by more patients randomized to liraglutide than to placebo, across CKD subgroups and albuminuria subgroups (interaction P value nonsignificant for all) (Figure 2, A and B).

Risk of severe hypoglycemia was significantly lower in patients with CKD randomized to liraglutide versus placebo (HR, 0.63; 95% CI, 0.43 to 0.91). In those without CKD, there was a nonsignificant but numerically lower risk of severe hypoglycemia with liraglutide (HR, 0.81; 95% CI, 0.59 to 1.12). Overall, no significant interaction between treatment and subgroup was apparent (interaction P=0.31; Figure 2A). In patients with albuminuria, severe hypoglycemia risk was significantly lower with liraglutide versus placebo (HR, 0.57; 95% CI, 0.40 to 0.82), but this was not the case in those without albuminuria (HR, 0.99; 95% CI, 0.70 to 1.40) (Figure 2B), generating a significant interaction between treatment and the two subgroups (interaction P=0.03).

The rate of diabetic foot ulcer events was similar with liraglutide and placebo in both the CKD and albuminuria subgroups, and there was no interaction between treatment and subgroup (interaction P=0.48 and 0.53, respectively; Figure 2, A and B).

Risk of bone and joint injuries was significantly lower in patients with CKD randomized to liraglutide versus placebo (HR, 0.48; 95% CI, 0.24 to 0.97). In those without CKD, there was a nonsignificant but numerically lower risk of bone and joint injury with liraglutide (HR, 0.76; 95% CI, 0.46 to 1.26). Overall, no significant interaction between treatment and subgroup was apparent (interaction P=0.31; Figure 2A). In patients with albuminuria, risk of bone and joint injuries occurred at a similar rate across liraglutide and placebo groups in patients with and without albuminuria; there was no interaction between treatment and subgroup (interaction P=0.65; Figure 2B).

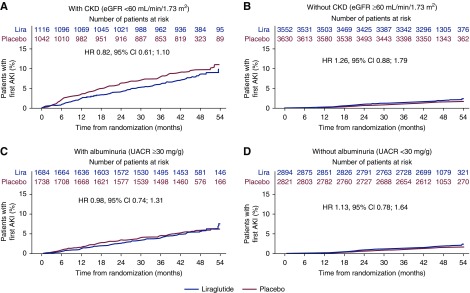

Overall, AKI occurred more frequently in patients with CKD than in those without (Figure 3, A and B); however, the risk of AKI was not increased with liraglutide treatment in those with CKD (HR, 0.82; 95% CI, 0.61 to 1.10) or without CKD (HR, 1.26; 95% CI, 0.88 to 1.79; interaction P=0.68; Figure 3, A and B) when compared with placebo. Likewise, the risk of AKI in patients with albuminuria was not increased with liraglutide treatment in those with albuminuria (HR, 0.98; 95% CI, 0.74 to 1.31) or without albuminuria (HR, 1.13; 95% CI, 0.78 to 1.64) versus with placebo (interaction P=0.57; Figure 3, C and D). There was also no indication of increased risk of AKI with liraglutide within the early trial phase in any of the CKD or albuminuria subgroups (Figure 3, A–D).

Figure 3.

Time to first AKI in those with and without CKD, and with and without albuminuria at baseline.

Gastrointestinal Adverse Events Leading to Permanent Discontinuation

Nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea leading to permanent discontinuation occurred in more patients randomized to liraglutide than placebo across all subgroups, although the differences were NS. Rates of nausea were similar in patients with CKD (2% versus 0.6%, liraglutide versus placebo, respectively) and patients without CKD (2% versus 0.3%, liraglutide versus placebo, respectively). Similarly, more patients randomized to liraglutide than placebo discontinued treatment because of those gastrointestinal (GI) adverse events in the albuminuria subgroups (2% versus 0.3% in the normoalbuminuria subgroup, liraglutide versus placebo, respectively; 1% versus 0.5% in the micro- and macroalbuminuria subgroups, liraglutide versus placebo, respectively).

Vomiting events were numerically higher in patients with CKD (0.9% versus 0%, liraglutide and placebo, respectively) compared with those without (0.6% versus 0.1%, liraglutide and placebo, respectively). In the albuminuria subgroups, discontinuation because of vomiting was more frequent in patients treated with liraglutide, whether they had normoalbuminuria (0.6% versus 0%, liraglutide versus placebo, respectively) or micro- and macroalbuminuria (0.8% versus 0.1%, liraglutide versus placebo, respectively).

Diarrhea was also more often reported in patients with CKD on liraglutide (1% versus 0.2%, liraglutide and placebo, respectively) compared with those without CKD (0.4% versus 0.1%, liraglutide and placebo, respectively). Discontinuation because of diarrhea in the albuminuria subgroups was also higher in patients treated with liraglutide in the normoalbuminuria (0.6% versus 0.1%, liraglutide versus placebo, respectively) and micro- and macroalbuminuria subgroups (0.5% versus 0.2%, liraglutide versus placebo, respectively).

Discussion

This post hoc analysis suggests that liraglutide has a comparable safety profile in patients with type 2 diabetes with and without CKD (defined here as eGFR <60 or ≥60 ml/min per 1.73 m2, respectively) and even in CKD stage 4. As expected, a higher proportion of patients with CKD experienced serious adverse events and severe hypoglycemia episodes compared with those without CKD; however, the risk was similar among those allocated to liraglutide and placebo. In fact, in the full LEADER trial population, treatment with liraglutide led to significantly fewer severe hypoglycemia events, but more acute gallbladder disease and more GI events (nausea, vomiting, and diarrhea) that led to discontinuation compared with placebo (21). Those differences between liraglutide and placebo were independent of eGFR or urine albumin. Also, no unexpected increase of AKI was observed among liraglutide versus placebo users.

Despite the GLP-1RA drug class being clinically available for >10 years, few studies have focused on the safety and efficacy of GLP-1RAs in the setting of CKD (11,20,28–32). The results from this post hoc analysis provide a sound basis to consider safety aspects of liraglutide in patients with CKD. Liraglutide, the pharmacokinetics of which are largely kidney independent, is one of the few glucose-lowering agents that can be used in patients with CKD stages 1–4, without dose adjustment. Liraglutide is also one of the few drugs used in type 2 diabetes treatment that has been shown to reduce major cardiovascular outcomes, all-cause mortality, and kidney outcomes in patients at high cardiovascular risk (16,21). Clinical evidence also shows that a cardiovascular benefit is evident with liraglutide treatment in patients with and without CKD and type 2 diabetes (20), as suggested by a significant interaction of the CKD versus no CKD subgroups on the treatment effect for the primary cardiovascular outcome (20,21).

The SGLT-2i trials EMPA-REG (Empagliflozin Cardiovascular Outcome Event Trial in Type 2 Diabetes Mellitus Patients) (33), CANVAS (Canagliflozin Cardiovascular Assessment Study) (34), and CREDENCE (Canagliflozin and Renal Outcomes in Type 2 Diabetes and Nephropathy) (15) have also reported beneficial effects on cardiovascular outcomes and all-cause death in those with and without CKD. However, empagliflozin is not indicated for patients with an eGFR <45 ml/min per 1.73 m2, and canagliflozin is not currently recommended in patients with an eGFR <45 ml/min per 1.73 m2, hence their use is limited in patients with an eGFR ≥45 ml/min per 1.73 m2. This may change for canagliflozin after the recent results from CREDENCE that included patients with an eGFR as low as 30 ml/min per 1.73 m2 (15).

A previous 26-week randomized controlled trial examined the safety of liraglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes and moderate CKD (eGFR 30–59 ml/min per 1.73 m2) and also demonstrated no unexpected safety or tolerability issues (11). Similarly, the once-weekly GLP-1RA dulaglutide has been shown to have an acceptable safety profile in patients with type 2 diabetes and moderate-to-severe CKD (31). Consistent with this report, higher drug withdrawals due to GI side effects were reported with liraglutide than placebo (11) and with dulaglutide compared with insulin glargine (31). Nausea and vomiting are among the symptoms of more advanced CKD stages, although the LEADER findings show no increased risk of nausea leading to treatment discontinuation in patients with CKD or albuminuria, compared with those without. Thus, although GI adverse events are known to be more prevalent in patients receiving liraglutide versus placebo, the latter difference did not appear to be greater in those with CKD compared with those without CKD or albuminuria. AKI is an adverse event of concern when studying drugs in a population with prevalent CKD, but no increased risk of AKI was observed with liraglutide versus placebo in patients with or without CKD or albuminuria—this is an important finding in this special population with increased risk of AKI events.

In LEADER, liraglutide was tested against placebo on a background of standard of care that represented the use of glucose-lowering drugs in approximately 88% of participants, including insulin use in approximately 45% of patients at baseline (21). In the placebo group of LEADER, more glucose-lowering drugs were adopted during the trial than in the liraglutide group (21,35). Under these conditions, hypoglycemia events, particularly severe hypoglycemia, were less frequently reported with liraglutide versus placebo (21). Because the risk of hypoglycemia was higher in those with CKD than in those without CKD, the absolute benefit on hypoglycemia of liraglutide versus placebo became substantially greater in those with CKD and albuminuria. This hypoglycemia benefit with liraglutide is of clinical interest because CKD is a significant risk factor for hypoglycemia development and the choice of alternative glucose-lowering drugs is restricted (36).

In line with the results of a recent post hoc analysis of data from LEADER looking at the effect of liraglutide on diabetes-related foot ulceration and associated complications (26), we did not observe an increase in risk of diabetic foot ulcer events with liraglutide versus placebo in those with or without CKD or albuminuria.

A significantly lower risk of bone and joint injury was observed with liraglutide compared with placebo in patients with CKD. An increased risk of bone and joint injury has previously been flagged as a potential issue with the use of SGLT-2is (37). However, it should be noted that data on bone and joint injuries were not systematically collected in LEADER, and only reported if a serious adverse event or an event of special interest was involved (e.g., as part of a diabetic foot ulcer event).

There were also no reports of differences in amputations or skin gangrene with liraglutide in patients with or without CKD (see Supplemental Tables 1A, 1B, 2, 3A, and 3B), concerns that were recently raised for other glucose-lowering drugs (15,38).

In addition to the post hoc nature of this analysis, there are other limitations. LEADER reported safety data for a 3.5- to 5.0-year follow-up period (21); therefore, it would be imprudent to predict the longer-term liraglutide effect in this CKD population. However, it is worth noting that LEADER had a longer duration than most other modern cardiovascular outcome trials (39). Furthermore, this analysis focuses on serious-adverse-event data and does not take into account nonserious adverse events, which were not systematically reported during the trial. In addition, the CKD subgroup in this trial was relatively small, of which approximately 200 patients had an eGFR <30 ml/min per 1.72 m2.

In conclusion, the safety profile of liraglutide versus placebo added to standard of care is consistent in patients with type 2 diabetes and CKD or albuminuria, as compared with patients without CKD or albuminuria. Overall, a greater absolute benefit of liraglutide on severe hypoglycemia was found in patients with CKD or albuminuria. The results of this safety analysis, together with the positive cardiovascular and kidney outcomes, both in the full trial population and specifically in patients with CKD, confirm and expand the positive risk/benefit profile of liraglutide.

Disclosures

Dr. Fonseca reports consultation fees from Abbott, AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly and Company, Intarcia Therapeutics, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and Takeda; speaker honoraria from AstraZeneca, Sanofi, Takeda; and research grants from Abbott, Asahi, Bayer, Eli Lilly and Company, Endo Barrier, Gilead Sciences, and Novo Nordisk. Dr. Idorn and Dr. von Scholten are full-time employees of Novo Nordisk. Prof. Mann reports consultancy fees from AstraZeneca, Bayer HealthCare, Boehringer Ingelheim, Celgene, Fresenius Medical Care, Novo Nordisk, and Vifor Pharma; speaker honoraria from B. Braun, Eli Lilly and Company, Medice, Novo Nordisk, and Vifor Pharma; and research support from the European Union. Dr. Mosenzon reports attendance at advisory boards and consulting for AstraZeneca, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly and Company, Janssen, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi; grants paid to institution as study physician by AstraZeneca/Bristol-Myers Squibb; research grant support through Hadassah Hebrew University Hospital from Novo Nordisk; and speaker honoraria from AstraZeneca/Bristol-Myers Squibb, Boehringer Ingelheim, Eli Lilly and Company, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novartis, Novo Nordisk, Sanofi, and Teva. Dr. Poulter reports speaker and advisory board honoraria from AstraZeneca, Novo Nordisk, Servier, and Takeda; research grants for his research group from the British Heart Foundation, Diabetes UK, Julius Clinical, and National Institute for Health Research Efficacy and Mechanism Evaluation. Dr. Rasmussen is a Novo Nordisk full-time employee and shareholder, and also owns a patent for liraglutide (US15/401651). Dr. Raz reports attendance at advisory boards and speaker’s bureau for AstraZeneca, Eli Lilly and Company, Merck Sharp & Dohme, Novo Nordisk, and Sanofi; consultation fees from AstraZeneca, BOL, Camereyes Ltd., DarioHealth, Diabot, Exscopia, Glcome Ltd., Insuline Medical, Medial EarlySign Ltd., and Orgenesis Ltd.; and stock/shares in BOL, Camereyes Ltd., DarioHealth, Diabot, GlucoMe Ltd., and Orgenesis Ltd.

Funding

This work was supported by Novo Nordisk.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the participants; investigators; trial-site staff; and the leadership, employees, and contractors of the sponsor who were involved in the conduct of the trial.

Medical writing and submission support were provided by Aneela Majid and Izabel James of Watermeadow Medical, an Ashfield company, part of UDG Healthcare plc, funded by Novo Nordisk.

Parts of this study’s data have been published in the form of an abstract for the American Heart Association’s 90th Scientific Session in 2017 (Circulation 136[Suppl 1]: A15035, 2017).

Prof. Mann had full access to all of the data in the study, takes responsibility for the integrity of the data and accuracy of the data analysis, and had final responsibility for the decision to submit for publication. All authors had access to the final study results and assume responsibility for its content.

Data Sharing Statement

The data analyzed for this publication are available from the corresponding author on request.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

See related editorial, “Liraglutide for the Treatment of Type 2 Diabetes and Safety in Diabetic Kidney Disease: Liraglutide and Diabetic Kidney Disease,” on pages 444–446.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.11881019/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Table 1A. Association between diastolic BP parameters and LVH (in cross-section) in unadjusted and adjusted analyses, along with model discrimination.

Supplemental Table 1B. Association between diastolic BP parameters and ESKD and in unadjusted and adjusted analyses, along with model discrimination.

Supplemental Table 2. Association between systolic BP parameters and risk of LVH during two-year follow-up, along with model discrimination.

Supplemental Table 3A. Association between systolic BP parameters and LVH in unadjusted and adjusted analyses using BP load as a categorical predictor along with model discrimination.

Supplemental Table 3B. Association between systolic BP parameters and ESKD in unadjusted and adjusted analyses using BP load as a categorical predictor along with model discrimination.

References

- 1.De Cosmo S, Viazzi F, Pacilli A, Giorda C, Ceriello A, Gentile S, Russo G, Rossi MC, Nicolucci A, Guida P, Di Bartolo P, Pontremoli R; AMD-Annals Study Group: Achievement of therapeutic targets in patients with diabetes and chronic kidney disease: Insights from the Associazione Medici Diabetologi Annals initiative. Nephrol Dial Transplant 30: 1526–1533, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Pálsson R, Patel UD: Cardiovascular complications of diabetic kidney disease. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis 21: 273–280, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Papademetriou V, Lovato L, Doumas M, Nylen E, Mottl A, Cohen RM, Applegate WB, Puntakee Z, Yale JF, Cushman WC; ACCORD Study Group: Chronic kidney disease and intensive glycemic control increase cardiovascular risk in patients with type 2 diabetes. Kidney Int 87: 649–659, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Keith DS, Nichols GA, Gullion CM, Brown JB, Smith DH: Longitudinal follow-up and outcomes among a population with chronic kidney disease in a large managed care organization. Arch Intern Med 164: 659–663, 2004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dreisbach AW, Lertora JJL: The effect of chronic renal failure on drug metabolism and transport. Expert Opin Drug Metab Toxicol 4: 1065–1074, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pecoits-Filho R, Abensur H, Betônico CCR, Machado AD, Parente EB, Queiroz M, Salles JE, Titan S, Vencio S: Interactions between kidney disease and diabetes: Dangerous liaisons. Diabetol Metab Syndr 8: 50, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Davies M, Chatterjee S, Khunti K: The treatment of type 2 diabetes in the presence of renal impairment: What we should know about newer therapies. Clin Pharmacol 8: 61–81, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Scheen AJ: Pharmacokinetics and clinical use of incretin-based therapies in patients with chronic kidney disease and type 2 diabetes. Clin Pharmacokinet 54: 1–21, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cavanaugh KL: Diabetes management issues for patients with chronic kidney disease. Clin Diabetes 25: 90–97, 2007 [Google Scholar]

- 10.Satirapoj B: Sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors with renoprotective effects. Kidney Dis (Basel) 3: 24–32, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Davies MJ, Bain SC, Atkin SL, Rossing P, Scott D, Shamkhalova MS, Bosch-Traberg H, Syrén A, Umpierrez GE: Efficacy and safety of liraglutide versus placebo as add-on to glucose-lowering therapy in patients with type 2 diabetes and moderate renal impairment (LIRA-RENAL): A randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Care 39: 222–230, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Penno G, Garofolo M, Del Prato S: Dipeptidyl peptidase-4 inhibition in chronic kidney disease and potential for protection against diabetes-related renal injury. Nutr Metab Cardiovasc Dis 26: 361–373, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Groop PH, Cooper ME, Perkovic V, Hocher B, Kanasaki K, Haneda M, Schernthaner G, Sharma K, Stanton RC, Toto R, Cescutti J, Gordat M, Meinicke T, Koitka-Weber A, Thiemann S, von Eynatten M: Linagliptin and its effects on hyperglycaemia and albuminuria in patients with type 2 diabetes and renal dysfunction: The randomized MARLINA-T2D trial. Diabetes Obes Metab 19: 1610–1619, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hramiak I, Vilsbøll T, Gumprecht J, Silver R, Hansen T, Pettersson J, Wilding J: Semaglutide treatment and renal function in the SUSTAIN 6 trial. Can J Diabetes 42: S42, 2018. 29650110 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Perkovic V, Jardine MJ, Neal B, Bompoint S, Heerspink HJL, Charytan DM, Edwards R, Agarwal R, Bakris G, Bull S, Cannon CP, Capuano G, Chu PL, de Zeeuw D, Greene T, Levin A, Pollock C, Wheeler DC, Yavin Y, Zhang H, Zinman B, Meininger G, Brenner BM, Mahaffey KW; CREDENCE Trial Investigators: Canagliflozin and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes and nephropathy. N Engl J Med 380: 2295–2306, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Mann JFE, Ørsted DD, Brown-Frandsen K, Marso SP, Poulter NR, Rasmussen S, Tornøe K, Zinman B, Buse JB; LEADER Steering Committee and Investigators: Liraglutide and renal outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 377: 839–848, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kelly MS, Lewis J, Huntsberry AM, Dea L, Portillo I: Efficacy and renal outcomes of SGLT2 inhibitors in patients with type 2 diabetes and chronic kidney disease. Postgrad Med 131: 31–42, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gerstein HC, Colhoun HM, Dagenais GR, Diaz R, Lakshmanan M, Pais P, Probstfield J, Riesmeyer JS, Riddle MC, Rydén L, Xavier D, Atisso CM, Dyal L, Hall S, Rao-Melacini P, Wong G, Avezum A, Basile J, Chung N, Conget I, Cushman WC, Franek E, Hancu N, Hanefeld M, Holt S, Jansky P, Keltai M, Lanas F, Leiter LA, Lopez-Jaramillo P, Cardona Munoz EG, Pirags V, Pogosova N, Raubenheimer PJ, Shaw JE, Sheu WH, Temelkova-Kurktschiev T; REWIND Investigators: Dulaglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes (REWIND): A double-blind, randomised placebo-controlled trial. Lancet 394: 121–130, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Davies MJ, D’Alessio DA, Fradkin J, Kernan WN, Mathieu C, Mingrone G, Rossing P, Tsapas A, Wexler DJ, Buse JB: Management of hyperglycemia in type 2 diabetes, 2018. A Consensus Report by the American Diabetes Association (ADA) and the European Association for the Study of Diabetes (EASD). Diabetes Care 41: 2669–2701, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mann JFE, Fonseca V, Mosenzon O, Raz I, Goldman B, Idorn T, von Scholten BJ, Poulter NR: Effects of liraglutide versus placebo on cardiovascular events in patients with type 2 diabetes Mellitus and chronic kidney disease. Circulation 138: 2908–2918, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Marso SP, Daniels GH, Brown-Frandsen K, Kristensen P, Mann JF, Nauck MA, Nissen SE, Pocock S, Poulter NR, Ravn LS, Steinberg WM, Stockner M, Zinman B, Bergenstal RM, Buse JB; LEADER Steering Committee; LEADER Trial Investigators: LEADER Trial Investigators: Liraglutide and cardiovascular outcomes in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 375: 311–322, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Novo Nordisk A/S: Victoza (liraglutide). Prescribing information highlights, 2017. Available at: https://www.accessdata.fda.gov/drugsatfda_docs/label/2017/022341s027lbl.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2020

- 23.Marso SP, Poulter NR, Nissen SE, Nauck MA, Zinman B, Daniels GH, Pocock S, Steinberg WM, Bergenstal RM, Mann JF, Ravn LS, Frandsen KB, Moses AC, Buse JB: Design of the liraglutide effect and action in diabetes: Evaluation of cardiovascular outcome results (LEADER) trial. Am Heart J 166: 823–830.e5, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stevens LA, Coresh J, Greene T, Levey AS: Assessing kidney function--measured and estimated glomerular filtration rate. N Engl J Med 354: 2473–2483, 2006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.US Department of Health and Human Services: Food and Drug Administration, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER): Determining the extent of safety data collection needed in late-stage premarket and postapproval clinical investigations - Guidance for Industry, 2016. Available at: https://www.fda.gov/downloads/drugs/guidances/ucm291158.pdf. Accessed February 12, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed]

- 26.Dhatariya K, Bain SC, Buse JB, Simpson R, Tarnow L, Kaltoft MS, Stellfeld M, Tornøe K, Pratley RE; LEADER Publication Committee on behalf of the LEADER Trial Investigators: The impact of liraglutide on diabetes-related foot ulceration and associated complications in patients with type 2 diabetes at high risk for cardiovascular events: Results from the LEADER trial. Diabetes Care 41: 2229–2235, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Alexiadou K, Doupis J: Management of diabetic foot ulcers. Diabetes Ther 3: 4, 2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Idorn T, Knop FK, Jørgensen MB, Jensen T, Resuli M, Hansen PM, Christensen KB, Holst JJ, Hornum M, Feldt-Rasmussen B: Safety and efficacy of liraglutide in patients with type 2 diabetes and end-stage renal disease: An investigator-initiated, placebo-controlled, double-blind, parallel-group, randomized trial. Diabetes Care 39: 206–213, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jacobsen LV, Hindsberger C, Robson R, Zdravkovic M: Effect of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics of the GLP-1 analogue liraglutide. Br J Clin Pharmacol 68: 898–905, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Linnebjerg H, Kothare PA, Park S, Mace K, Reddy S, Mitchell M, Lins R: Effect of renal impairment on the pharmacokinetics of exenatide. Br J Clin Pharmacol 64: 317–327, 2007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Tuttle KR, Lakshmanan MC, Rayner B, Busch RS, Zimmermann AG, Woodward DB, Botros FT: Dulaglutide versus insulin glargine in patients with type 2 diabetes and moderate-to-severe chronic kidney disease (AWARD-7): A multicentre, open-label, randomised trial. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol 6: 605–617, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.von Scholten BJ, Persson F, Rosenlund S, Hovind P, Faber J, Hansen TW, Rossing P: The effect of liraglutide on renal function: A randomized clinical trial. Diabetes Obes Metab 19: 239–247, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wanner C, Inzucchi SE, Lachin JM, Fitchett D, von Eynatten M, Mattheus M, Johansen OE, Woerle HJ, Broedl UC, Zinman B; EMPA-REG OUTCOME Investigators: Empagliflozin and progression of kidney disease in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 375: 323–334, 2016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Neal B, Perkovic V, Mahaffey KW, de Zeeuw D, Fulcher G, Erondu N, Shaw W, Law G, Desai M, Matthews DR; CANVAS Program Collaborative Group: Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 377: 644–657, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Zinman B, Nauck MA, Bosch-Traberg H, Frimer-Larsen H, Ørsted DD, Buse JB; LEADER Publication Committee on behalf of the LEADER Trial Investigators: Liraglutide and glycaemic outcomes in the LEADER trial. Diabetes Ther 9: 2383–2392, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Moen MF, Zhan M, Hsu VD, Walker LD, Einhorn LM, Seliger SL, Fink JC: Frequency of hypoglycemia and its significance in chronic kidney disease. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 4: 1121–1127, 2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ye Y, Zhao C, Liang J, Yang Y, Yu M, Qu X: Effect of sodium-glucose Co-transporter 2 inhibitors on bone metabolism and fracture risk. Front Pharmacol 9: 1517, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Neal B, Perkovic V, Matthews DR: Canagliflozin and cardiovascular and renal events in type 2 diabetes. N Engl J Med 377: 2099, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Cefalu WT, Kaul S, Gerstein HC, Holman RR, Zinman B, Skyler JS, Green JB, Buse JB, Inzucchi SE, Leiter LA, Raz I, Rosenstock J, Riddle MC: Cardiovascular outcomes trials in type 2 diabetes: Where do we go from here? Reflections from a diabetes care editors’ expert forum. Diabetes Care 41: 14–31, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.