Consent in the initiation of dialysis is a visible way of endorsing the respect for patient autonomy, shared decision-making, and patient-centered care. Informed consent encompasses both doctors’ duty to inform patients about the nature, risks, and benefits of potential treatments, and subsequently the right of competent persons to make decisions about their health care. Consent for medical treatment is legally enshrined in common law jurisdictions, and must incorporate considerations of competence, voluntariness, and adequate provision and understanding of information, including prognosis, material risks, and treatment options other than dialysis (1). Our international nephrology community does not strictly follow this pathway every time a patient commences dialysis (1), leading to compromises in patient autonomy and their ability to make a choice.

When patients consent for dialysis, they are consenting for much more than cannulation of their fistula and the few hours they sit while their blood circulates through a machine. The effect of maintenance dialysis on a person’s overall health, diet, symptoms, function, lifestyle, and family is significant and extends far beyond the hours spent on dialysis, whether at home or in hospital (2).

Nephrology as a discipline strongly endorses shared decision-making in the initiation of dialysis (3). To do this, we have a duty to inform, because as common law states, “choice is, in reality, meaningless unless it is made on the basis of the relevant information and advice” (Rogers v Whitaker, paragraph 14 [4]). Furthermore, risks of treatment must be disclosed, including “the effect which its occurrence would have upon the life of the patient, the importance to the patient of the benefits sought to be achieved by the treatment, the alternatives available, and the risks involved in those alternatives” (Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board, paragraph 89 [5]).

To fulfill our duty to inform, information must be comprehensive, easy to understand, and individualized to the life of our patients and their families. It is important ethically and legally that information is not merely provided by the professional, but also adequately understood, carefully considered, and appropriate to the individual. The complexity of dialysis and its far-reaching effects on a patient’s life warrant discussion from a multidisciplinary team including nephrology, nursing, social work, and dietetics, and with adequate time allowanced over several visits.

In developed countries, increasingly large numbers of patients with ESKD are frail, elderly, and highly comorbid. For many, dialysis will confer poor prognosis, high symptom burden, functional decline, and significantly affect their quality of life and that of their families. Information about likely survival, new symptoms on dialysis, and the alternative of nondialysis management are particularly pertinent to these patients. Yet procedural aspects tend to take priority, and consent often is implied when patients attend hospital to undergo dialysis or home dialysis training. With dialysis framed as a default, patients and families do not perceive a choice, and are not aware of what lies ahead (6). Even if more comprehensive information has been provided, without carefully checking for understanding, dialysis attendance validates little beyond an awareness of dialysis schedule. This current practice of consenting for dialysis falls below ethical and legal standards internationally (1).

It is imperative that the nephrology community improves informed consent in accordance with legal and ethical benchmarks, and we propose two ways to achieve this. First, information should be both written and verbal, provided by a multidisciplinary team, and must include all the aspects prescribed by law, including how treatment affects a person’s life and the alternatives available, as described in Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board (5). As an example, our nephrology unit provides patients a brochure alongside verbal education, outlining in simple language what dialysis is, its procedure, potential benefits and risks, likely survival with or without dialysis (on the basis of local data), the alternative of medical management without dialysis, and considerations about the individual’s values and preferences (7). This ensures that the important but difficult conversations about prognosis are not omitted, and provides a record of information for patients to take home, consider, and share with their families. Furthermore, we have an explicit pathway for medical management without dialysis (8), framing dialysis as a treatment choice rather than a necessity.

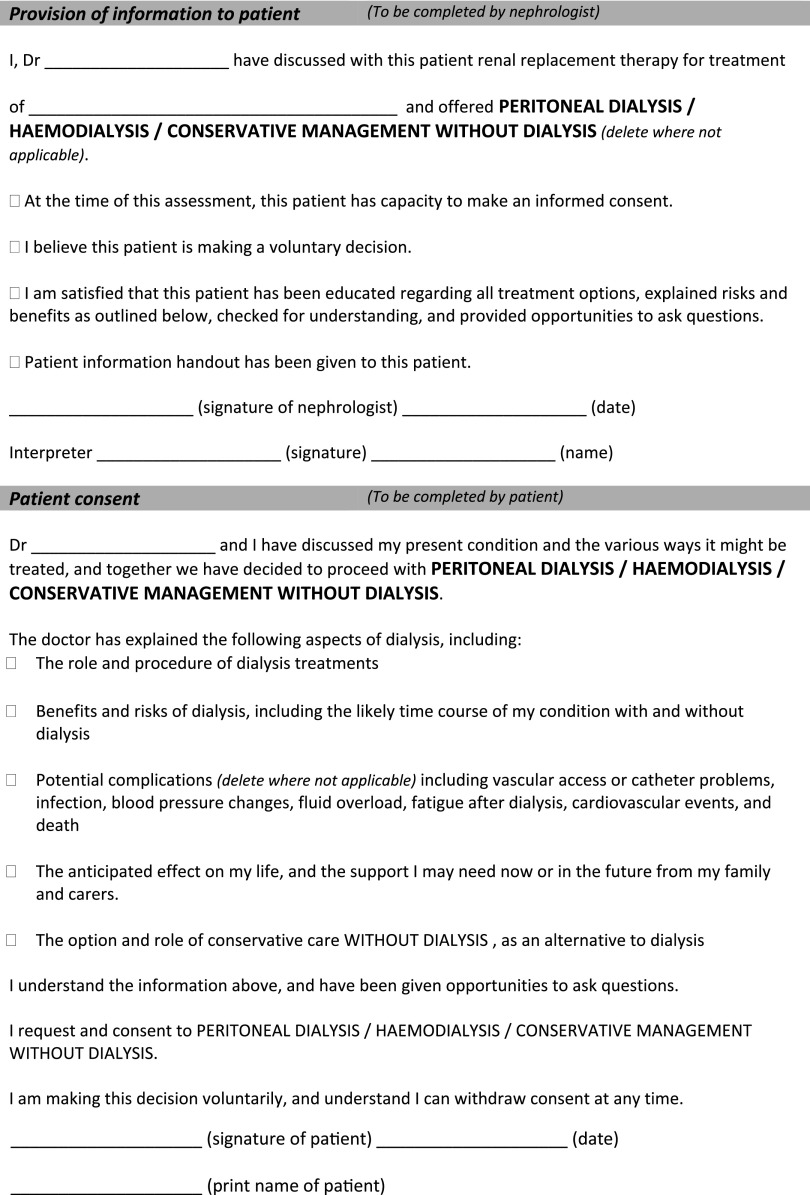

Second, a dialysis consent form (proposed in Figure 1) should be signed to capture this shared decision-making process, and include elements of capacity, voluntariness, and provision and understanding of information, including prognosis and the alternative of management without dialysis. The complexity of decision-making warrants discussions early in the disease, led by the nephrologist, with consent completed weeks to months before a patient commences dialysis and reaffirmed at dialysis initiation.

Figure 1.

Proposed dialysis options consent form, incorporating capacity, voluntariness, and the provision and understanding of information about dialysis and its alternative.

A consent form is a useful tool but of itself does not equate to informed consent. Consent is a process of communication that allows doctors to provide dialysis to our patients, who must understand its consequences as they are applied personally. Consenting patients for dialysis is essential in nephrology practice, and as nephrologists we must do this well before committing patients to such life-changing treatment. Putting aside the legal aspects, we must do this well if we are to value and respect autonomy, understanding that even with the inherent vulnerability of having a serious life limiting illness, competent adults can and should make informed choices about their health care. We must do this well if we genuinely endorse shared decision-making, which must be based on open and transparent discussion, including the particularly difficult conversations about prognosis and the burdens of disease and treatment. We must also accept that despite technical expertise, the best interests of patients encompass many aspects of life beyond their illness, which we may not always appreciate. And lastly, patients have the right to refuse dialysis, a voice of refusal that may be loud or subtle (9), but we must listen to it carefully.

Consent is not just a legal requirement. It is about nephrologists’ willingness to meet high ethical standards and show respect for patients and their families. It is also a process likely to reduce the burden of moral distress as expectations of dialysis outcomes become realistic from the outset. Provision of informed consent to commence dialysis means that our patients are making a properly informed choice to do so. What do we as an international nephrology community need to do to achieve this aim?

Disclosures

Prof. Brown and Dr. Li have nothing to disclose.

Acknowledgments

The content of this article does not reflect the views or opinions of the American Society of Nephrology (ASN) or CJASN. Responsibility for the information and views expressed therein lies entirely with the author(s).

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

References

- 1.Brennan F, Stewart C, Burgess H, Davison SN, Moss AH, Murtagh FEM, Germain M, Tranter S, Brown M: Time to improve informed consent for dialysis: An international perspective. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1001–1009, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goto NA, van Loon IN, Boereboom FTJ, Emmelot-Vonk MH, Willems HC, Bots ML, Gamadia LE, van Bommel EFH, Van de Ven PJG, Douma CE, Vincent HH, Schrama YC, Lips J, Hoogeveen EK, Siezenga MA, Abrahams AC, Verhaar MC, Hamaker ME: Association of initiation of maintenance dialysis with functional status and caregiver burden. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 14: 1039–1047, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Renal Physicians Association and American Society of Nephrology: Shared Decision-Making in the Appropriate Initiation of and Withdrawal from Dialysis, Rockville, MD, Renal Physicians Association, 2000 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Rogers v Whitaker [1992] HCA 58; 175 CLR 479.

- 5. Montgomery v Lanarkshire Health Board [2015] UKSC 11.

- 6.O’Hare AM, Armistead N, Schrag WLF, Diamond L, Moss AH: Patient-centered care: An opportunity to accomplish the “three aims” of the National quality strategy in the Medicare ESRD program. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 9: 2189–2194, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Renal Department St George and Sutherland Hospitals: Information for Patients about Advanced Kidney Disease Dialysis and Non-Dialysis Treatments, 2018. Available at: https://stgrenal.org.au/sites/default/files/upload/Predialysis/Patient information about dialysis 2018_V2.pdf. Accessed November 11, 2019

- 8.Brown MA, Collett GK, Josland EA, Foote C, Li Q, Brennan FP: CKD in elderly patients managed without dialysis: Survival, symptoms, and quality of life. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 10: 260–268, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Wong SPY, McFarland LV, Liu CF, Laundry RJ, Hebert PL, O’Hare AM: Care practices for patients with advanced kidney disease who forgo maintenance dialysis. JAMA Intern Med 179: 305–313, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]