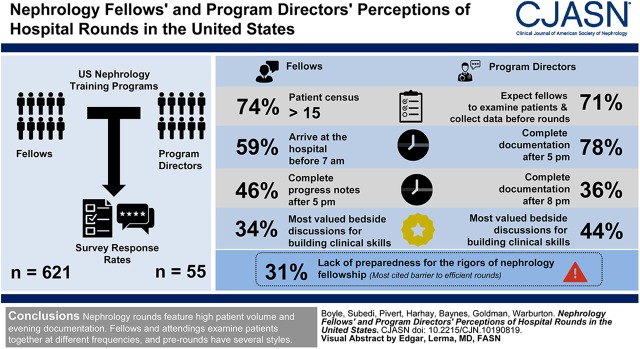

Visual Abstract

Keywords: clinical nephrology, Clinical Competence, Workload, Teaching Rounds, Problem-Based Learning, Censuses, Workflow, Motivation, Records, Surveys and Questionnaires, Training Support, Patient Care, Documentation

Abstract

Background and objectives

Hospital rounds are a traditional vehicle for patient-care delivery and experiential learning for trainees. We aimed to characterize practices and perceptions of rounds in United States nephrology training programs.

Design, setting, participants, & measurements

We conducted a national survey of United States nephrology fellows and program directors. Fellows received the survey after completing the 2019 National Board of Medical Examiners Nephrology In-Training Exam. Program directors received the survey at the American Society of Nephrology’s 2019 Nephrology Training Program Directors’ Retreat. Surveys assessed the structure and perceptions of rounds, focusing on workload, workflow, value for patient care, and fellows’ clinical skill-building. Directors were queried about their expectations for fellow prerounds and efficiency of rounds. Responses were quantified by proportions.

Results

Fellow and program director response rates were 73% (n=621) and 70% (n=55). Most fellows (74%) report a patient census of >15, arrive at the hospital before 7:00 am (59%), and complete progress notes after 5:00 pm (46%). Among several rounding activities, fellows most valued bedside discussions for building their clinical skills (34%), but only 30% examine all patients with the attending at the bedside. Most directors (71%) expect fellows to both examine patients and collect data before attending-rounds. A majority (78%) of directors commonly complete their documentation after 5:00 pm, and for 36%, after 8:00 pm. Like fellows, directors most value bedside discussion for development of fellows’ clinical skills (44%). Lack of preparedness for the rigors of nephrology fellowship was the most-cited barrier to efficient rounds (31%).

Conclusions

Hospital rounds in United States nephrology training programs are characterized by high patient volumes, early-morning starts, and late-evening clinical documentation. Fellows use a variety of prerounding styles and examine patients at the beside with their attendings at different frequencies.

Podcast

This article contains a podcast at https://www.asn-online.org/media/podcast/CJASN/2020_03_17_CJN.10190819.mp3

Introduction

Hospital rounds are the cornerstone of care delivery for hospitalized patients and the primary source of experiential learning for medical trainees. An effective rounds experience satisfies the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education’s (ACGME) requirement for patient-based teaching that involves direct interaction between trainees and attendings, bedside learning, discussion of pathophysiology, and the use of current evidence in diagnostic and therapeutic decisions (1). However, demands such as trainee duty-hour restrictions, high patient volume and turnover, and clerical burden often impede the ability of rounds to combine high-quality patient care, high educational value for trainees, and efficiency (2). The ACGME offers no specific guidelines on how to achieve high-quality, efficient rounds.

Over the past several decades, physicians’ time has shifted from direct care at the bedside toward indirect care activities like documentation in the electronic medical record (EMR). Time-in-motion studies estimate that current internal medicine residents spend only 9%–13% of their time in direct patient care, down from approximately 25% during the 1990s (3–6). This increase in indirect-care activity has been closely associated with the current epidemic of physician burnout (7–9). Alternative models for rounds have evolved in response to these demands on time. Two are card-flip rounds and discovery rounds. In card-flip rounds, trainees and attendings examine patients independently of one another and meet away from the bedside to discuss care plans (10). In discovery rounds, trainees and attendings perform all clinical activities together, including patient data collection and bedside examination, eliminating the need for prerounds (11).

Medical educators in a variety of specialties have studied nontraditional rounding models in an effort to improve patient care and safety, optimize the clinical learning environment for trainees, and prevent burnout (12–17). Little has been published about hospital rounds in nephrology training programs, and the unique challenges that nephrologists routinely confront may decrease the generalizability of other specialties’ approaches. First, most nephrologists serve as consultants in the hospital and not primary care providers. Second, nephrology patients rank among the most medically complex, often requiring disproportionally more time and resources (18). Third, nephrology is experiencing a recruitment crisis. In the past 5 years, only 60% of positions have filled through the National Residency Match Program, with a minority filled by United States graduates (19–21). Failure to recruit nephrology trainees is partly attributable to medical residents’ and students’ perception that nephrologists have heavy clinical workloads (20,22).

Development of evidence-based guidelines for hospital nephrology rounds has the potential to improve patient care, assist fellows in attaining core competencies, prevent physician burnout, and attract new learners to the specialty. As an initial step, current practices and perceptions of hospital rounds in United States nephrology training programs must be identified. Therefore, in a survey of United States nephrology fellows, we sought to (1) characterize the general structure of rounds during a typical day on the inpatient consult service (workload, workflow, frequency of bedside examination with the attending), and (2) assess the perceived value of specific activities on rounds for either development of fellows’ clinical skills or patient care. In a survey of nephrology training program directors and associate program directors, we assessed (1) expectations for fellows’ preparation for rounds with the attending; (2) general structure of rounds (workflow and workload); and (3) the perceived value of certain rounding activities for developing fellows’ clinical skills, patient care, and rounding efficiency.

Materials and Methods

Survey Audience

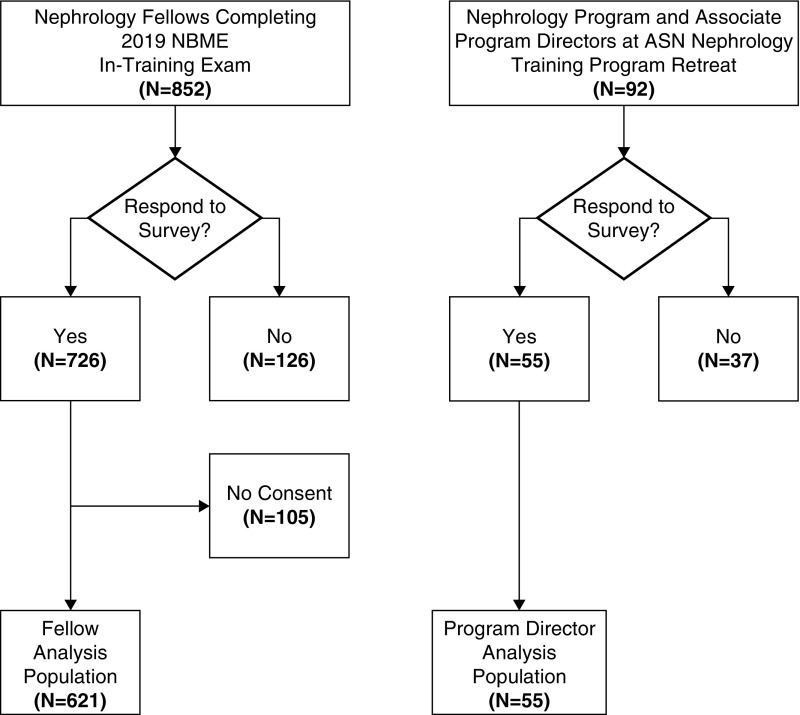

United States nephrology fellows who sat for the National Board of Medical Examiners 2019 Nephrology In-Training Exam were presented with the fellow survey questionnaire at its conclusion (n=852). A separate questionnaire was administered to nephrology program directors and associate directors who attended the 2019 American Society of Nephrology (ASN) Nephrology Training Program Directors’ Retreat (n=92) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Description of the survey audiences for the fellow and program director surveys. ASN, American Society of Nephrology, NBME, National Board of Medical Examiners.

Survey Instrument Design

We designed the questionnaire with the a priori objective of understanding the general structure of rounds and the perceived value of certain rounding activities for fellows’ clinical skills development and patient care. Domains and subdomains (Table 1) were derived through discussion with expert nephrology educators and review of the graduate medical education literature. Expert nephrology educators from three separate university-based nephrology programs reviewed drafts of the questionnaires and provided feedback to improve face and content validity and reliability. The questionnaires were then tested by six non-nephrology internal medicine medical subspecialty fellows and a 2018 nephrology fellowship graduate, all from Drexel University. This test group included both men and women, and United States and international graduates. The questionnaires were revised iteratively based on the responses and feedback of the test group. The ASN Workforce and Training Committee reviewed the survey objectives and instruments, providing general feedback and ensuring that the instruments did not exceed the question limits.

Table 1.

Survey domains and subdomains

| Survey Domains and Subdomains | No. of Questions |

|---|---|

| Fellow survey | 9 |

| Structure of rounds | 6 |

| Workload | 2 |

| Patient census (per fellow) | 1 |

| Other clinical responsibilities | 1 |

| Workflow | 4 |

| Time of hospital arrival | 1 |

| Use of technology on rounds | 1 |

| Prerounds activity | 1 |

| Time of progress note completion | 1 |

| Frequency of bedside examination with attending | 1 |

| Perceptions of rounds | 2 |

| Value for clinical skill building | 1 |

| Value for patient care | 1 |

| Program director survey | 11 |

| Expectations for preparation for attending-rounds | 2 |

| Structure of rounds | 3 |

| Workload | 1 |

| Workflow | 2 |

| Perceptions of rounds | 6 |

| Value for clinical skill-building | 2 |

| Value for patient care | 2 |

| Efficiency | 2 |

The fellow questionnaire was administered in electronic form at the end of the 2019 Nephrology In-Training Exam. Deidentified demographic information, including sex, year of fellowship, fellowship program size, and type of medical school were collected. Nine additional questions measured two broad domains and several subdomains (Table 1).

A paper questionnaire of 11 questions mapped to three broad domains and several subdomains was administered to program directors (Table 1). Survey instruments are provided in Supplemental Appendix 1.

The surveys instruments and protocol were approved by the Drexel University Institutional Review Board and are consistent with the principles of the Declaration of Helsinki. Question response types included single-best-response multiple choice, select-all-that-apply multiple choice, Likert scale, and rank (1=highest value, 5=lowest value).

Statistical Analyses

Fellow baseline characteristics and survey response distributions are reported as proportions. Chi-squared tests and Fisher exact test were used to test the association of fellow survey subdomains of workload with workflow. A multinomial, multivariable, logistic regression model identified factors associated with time of progress note completion. Statistical significance was set at a two-tailed α<0.05.

We report the proportion of missing data owing to nonresponse for each survey measurement. For rank-style questions on the program director survey, we report the proportion of first-rank response. In the statistical analyses, we performed pairwise deletion, resulting in an available case analysis, where cases were excluded only if data were missing on a required variable.

All analyses were conducted using SAS, version 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) (23). Visualizations were developed with ggplot2 and R (24).

Results

Fellow Survey

Among 852 nephrology fellows who took the 2019 Nephrology In-Training Exam, 726 (85%) responded to the survey and 621 (73%) consented to inclusion in the analysis (Figure 1). The item-response rate was >97%.

The majority of fellow participants were men (68%), in their first year of fellowship (48%), and graduates of medicals schools outside the United States (65%). Of graduates from United States schools, 26% were from allopathic programs (n=160). Baseline characteristics are summarized in Table 2.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the fellow survey respondents

| Parameter | All, n=621 |

|---|---|

| Sex | |

| Male | 388 (62%) |

| Current yr of fellowship training | |

| 1st yr | 296 (48%) |

| 2nd yr | 293 (47%) |

| 3rd yr | 21 (3%) |

| 4th yr | 7 (1%) |

| Missing | 4 (0.64%) |

| Size of the fellowship training program | |

| 1–4 fellows | 178 (29%) |

| 5–8 fellows | 240 (39%) |

| 9–11 fellows | 131 (21%) |

| ≥12 fellows | 69 (11%) |

| Missing | 3 (0.48%) |

| Type of medical school | |

| United States, allopathic | 160 (26%) |

| United States, osteopathic | 53 (9%) |

| Canadian, allopathic | 6 (0.97%) |

| United States, off-shore | 38 (6%) |

| International, Europe | 29 (5%) |

| International, Middle East | 76 (12%) |

| International, Asia | 193 (31%) |

| International, Latin America | 40 (6%) |

| International, Africa | 19 (3%) |

| Missing | 7 (1%) |

Values are expressed as count (percent).

Structure of Rounds.

Most fellows (74%) reported a census of >15 patients, 36% reported >21, and 19% reported an average of 11–15 patients per service (Table 3). Most (70%) reported arriving at the hospital between 6:00 am and 7:30 am, 12% reported arriving before 6:00 am, and 14% reported arriving after 7:30 am. Forty six percent reported “rarely” or “never” collecting patient data without interviewing and examining patients at the bedside before attending-rounds, 23% reported “sometimes,” and 29% reported “most of the time” or “always.” Most (85%) reported using at least one type of technology during rounds, commonly a mobile phone application to view patient data (53%). Voice-recognition software to dictate progress notes was the least used (16%). Nearly all (95%) reported at least one other clinical responsibility (outpatient clinic, kidney biopsy, or dialysis catheter placement) when rounding in the hospital; 30% reported all three. Nearly half of fellow participants (45%) reported completing their progress notes between noon and 5:00 pm; 46% reported completing their progress notes after 5:00 pm. Most (60%) reported examining the majority of the patients at the bedside with the attending, but only 30% reported seeing all patients with the attending (Supplemental Tables 1 and 2).

Table 3.

Fellow survey responses: structure and perceptions of hospital nephrology rounds

| Parameter | All, n=621a | Domain/Subdomain | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Average patient census (per fellow)b | Domain: structure subdomain: workload | ||

| 0–4 patients | 6 (0.97%) | ||

| 5–10 patients | 24 (4%) | ||

| 11–15 patients | 118 (19%) | ||

| 16–20 patients | 224 (36%) | ||

| ≥21 patients | 237 (38%) | ||

| Missing | 12 (2%) | ||

| Hospital arrival time for a day shiftb | Domain: structure subdomain: workflow | ||

| Before 6:00 am | 75 (12%) | ||

| 6:01 am–6:30 am | 128 (21%) | ||

| 6:31 am–7:00 am | 163 (26%) | ||

| 7:01 am–7:30 am | 144 (23%) | ||

| 7:31 am–8:00 am | 84 (14%) | ||

| After 8:01 am | 13 (2%) | ||

| Missing | 14 (2%) | ||

| Time of progress note completionb | Domain: structure subdomain: workflow | ||

| Before 10:00 am | 8 (1%) | ||

| 10:01 am–12:00 pm | 36 (6%) | ||

| 12:01 pm–5:00 pm | 279 (45%) | ||

| 5:01 pm–8:00 pm | 263 (42%) | ||

| After 8:01 pm | 22 (4%) | ||

| Missing | 13 (2%) | ||

| Frequency of patient data (vital signs, laboratory results) collection without interviewing and examining patients before rounding with the attendingb | Domain: structure subdomain: workflow | ||

| Never | 130 (21%) | ||

| Rarely | 153 (25%) | ||

| Sometimes | 142 (23%) | ||

| Most of the time | 99 (16%) | ||

| Always | 83 (13%) | ||

| Missing | 14 (2%) | ||

| Proportion of patients examined together with the attendingb | Domain: structure subdomain: workflow | ||

| None | 31 (5%) | ||

| Less than half | 137 (22%) | ||

| Approximately half | 69 (11%) | ||

| More than half but not all | 185 (30%) | ||

| All | 185 (30%) | ||

| Missing | 14 (2%) | ||

| Type of technologyc | Domain: structure subdomain: workflow | ||

| Electronic tablets to view patient data | 189 (30%) | ||

| Mobile phone applications to view patient data | 332 (53%) | ||

| Mobile laptop computers to view and input data (e.g., notes and orders) | 242 (39%) | ||

| Voice-recognition software to dictate patient progress notes | 101 (16%) | ||

| Overall technology use | Domain: structure subdomain: workflow | ||

| At least one (tablet/phone/laptop/voice recognition) | 527 (85%) | ||

| No technology | 94 (15%) | ||

| Competing clinical responsibilities while roundingc | Domain: structure subdomain: workflow | ||

| Outpatient clinic | 556 (90%) | ||

| Performance of kidney biopsy | 330 (53%) | ||

| Placement of dialysis catheters | 286 (46%) | ||

| Number of competing clinical responsibilities | Domain: structure subdomain: workflow | ||

| 0 | 33 (5%) | ||

| 1 | 191 (30%) | ||

| 2 | 210 (34%) | ||

| 3 | 187 (30%) | ||

| Missing | 0 (0%) | ||

| Most valuable for building clinical skills as a nephrologist | Domain: perception subdomain: value for clinical skill-building | ||

| Analyzing laboratory results | 57 (9%) | ||

| Formulating a differential diagnosis and management plan by writing consults and progress notes | 138 (22%) | ||

| Bedside discussion of differential diagnosis and management plans with the attending | 210 (34%) | ||

| Remote discussion of differential diagnosis and management plans with the attending | 201 (32%) | ||

| Missing | 15 (2%) | ||

| Does interviewing and examining patients before attending-rounds improve patient care? | Domain: perception subdomain: value for patient care | ||

| Never | 12 (2%) | ||

| Rarely | 65 (10%) | ||

| Sometimes | 176 (28%) | ||

| Most of the time | 188 (30%) | ||

| Always | 159 (26%) | ||

| Missing | 21 (3%) | ||

Values are expressed as count (percent).

For a typical inpatient consult service during the week.

The responses for these questions are not mutually exclusive and the percent may not add to 100.

In a multivariable model that included program size (defined by the number of fellows), average patient census (per fellow), hospital arrival time, and use of technology (yes or no), only patient census had statistical significance with the time of progress-note completion. Compared with the reference group (completion between noon and 5:00 pm), the increase in odds of completing notes after 8:00 pm was 1.14 for each one-patient increase in census (95% confidence interval [95% CI], 1.01 to 1.28), with an odds ratio of 1.01 (95% CI, 1.05 to 1.15) for completing between 5:00 pm and 8:00 pm.

Perception of Rounds.

Of four different rounding activities (analysis of laboratory data, formulation of differential diagnosis/plans through progress/consult notes, bedside discussion of diagnosis/management with attendings, discussion of diagnosis/management with attendings remote to the bedside), fellows most valued discussion with the attending—either at the bedside (34%) or remotely (32%)—for development of their clinical skills. Most felt that interviewing and examining patients independently before attending-rounds improved patient care “most of the time” or “always” (56%; n=347).

Program Director Survey

Of 149 United States program directors and an estimated 77 associate directors, 92 attended the ASN’s Nephrology Training Program Directors’ Retreat on May 3–4, 2019, in Rosemont, Illinois. Attendees represented 68 of 149 United States training programs (47%) and 30 of 43 (70%) states with training programs (including the District of Columbia). The median approved program size was seven fellows (minimum, two; maximum, 19). Fifty five attendees (70%) responded to the survey, representing 24% of United States nephrology training program leadership (Table 4).

Table 4.

Program director survey responses: structure and perceptions of hospital nephrology rounds

| Parameter | All, n=55 | Domain/Subdomain | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Do faculty have concurrent clinical or administrative responsibility? | Domain: structure subdomain: workload | ||

| No | 4 (7%) | ||

| Yes | 51 (93%) | ||

| It is acceptable for fellows to collect patients’ data without examining the patients before rounding with the attending? | Domain: perception subdomain: perceived value | ||

| Strongly disagree | 9 (16%) | ||

| Disagree | 15 (27%) | ||

| Neither agree or disagree | 4 (7%) | ||

| Agree | 20 (36%) | ||

| Strongly agree | 7 (13%) | ||

| Do you expect your fellows to preround? | Domain: structure subdomain: workflow | ||

| No | 2 (4%) | ||

| Yes, but only to collect data, not to examine | 14 (25%) | ||

| Yes, both to collect data and to examine | 39 (71%) | ||

| When do you typically finish cosigning all fellows progress notes during a day shift on the inpatient consult service? | Domain: structure subdomain: workflow | ||

| 11 am to noon | 2 (4%) | ||

| Noon to 5 pm | 10 (18%) | ||

| 5 pm to 8 pm | 23 (42%) | ||

| After 8 pm | 20 (36%) | ||

| Type of technology during rounds on the inpatient consult servicea | Domain: structure subdomain: workflow | ||

| Electronic tablets | 18 (33%) | ||

| Mobile phone applications to view patient data | 36 (65%) | ||

| Laptops | 23 (42%) | ||

| Voice-recognition software to dictate patient progress notes | 15 (27%) | ||

| Number of technologies used | Domain: structure subdomain: workflow | ||

| 0 | 7 (13%) | ||

| 1 | 21 (38%) | ||

| 2 | 12 (22%) | ||

| 3 | 13 (24%) | ||

| 4 | 2 (4%) | ||

| Missing | 0 (0%) | ||

| Which do you consider the most valuable for building fellows’ clinical skills?b | Domain: perception subdomain: perceived value | ||

| Analyzing laboratory results | 15 (27%) | ||

| Formulating a differential diagnosis and management plan by writing consults and progress notes | 9 (16%) | ||

| Bedside discussion of differential diagnosis and management plan with attending | 24 (44%) | ||

| Remote discussion of differential diagnosis and management plans with attending | 5 (9%) | ||

| Which do you consider the most significant barrier to efficient rounds?b | Domain: perception subdomain: perceived efficiency | ||

| Electronic medical records | 15 (27%) | ||

| Trainee duty hours | 1 (2%) | ||

| Fellows unprepared for the clinical demands of nephrology fellowship | 17 (31%) | ||

| Competing clinical and administrative responsibility for faculty | 15 (27%) | ||

| Competing clinical responsibility for fellows | 6 (11%) | ||

| Patient care is improved when fellows interview and examine patients before rounding with the attending. | Domain: perception subdomain: perceived value | ||

| Strongly disagree | 3 (5%) | ||

| Disagree | 2 (4%) | ||

| Neither agree or disagree | 11 (20%) | ||

| Agree | 20 (36%) | ||

| Strongly agree | 19 (35%) | ||

| Fellows’ clinical skills improve when they interview and examine patients before rounding with the attending. | Domain: perception subdomain: perceived value | ||

| Disagree | 2 (4%) | ||

| Neither agree or disagree | 7 (13%) | ||

| Agree | 22 (40%) | ||

| Strongly agree | 24 (44%) | ||

| Patient care is improved when fellows and attendings interview and examine patients together. | Domain: perception subdomain: perceived value | ||

| Strongly disagree | 3 (5%) | ||

| Disagree | 8 (15%) | ||

| Neither agree or disagree | 16 (29%) | ||

| Agree | 18 (33%) | ||

| Strongly agree | 10 (18%) | ||

| How efficient are your clinical rounds on the inpatient consult services? | Domain: perception subdomain: perceived efficiency | ||

| Not efficient | 2 (4%) | ||

| Rarely efficient | 2 (4%) | ||

| Somewhat efficient | 23 (42%) | ||

| Efficient | 23 (42%) | ||

| Very efficient | 4 (7%) | ||

The responses for these questions are not mutually exclusive and the percent may not add to 100.

The responder ranked the preidentified options for these questions.

Expectations for Preparation for Attending-Rounds (“Prerounds”).

A majority (71%) of directors reported expecting fellows to collect patient data and examine patients before rounds with the attending. A quarter reported expecting fellows only to collect patient data before attending-rounds, and 4% (n=2) reported expecting fellows to neither collect data nor examine patients before attending-rounds.

Structure of Rounds.

Nearly all (93%) reported concurrent administrative or clinical responsibilities when attending on the hospital service. During rounds, 87% use at least one of the following technologies: electronic tablets, mobile phone applications, laptops, or voice-recognition software to dictate patient notes—most commonly, a mobile phone application (65%). Most (78%) typically finish addendums to fellow progress notes after 5:00 pm; 36% (n=20) complete them after 8:00 pm.

Perceptions of Rounds.

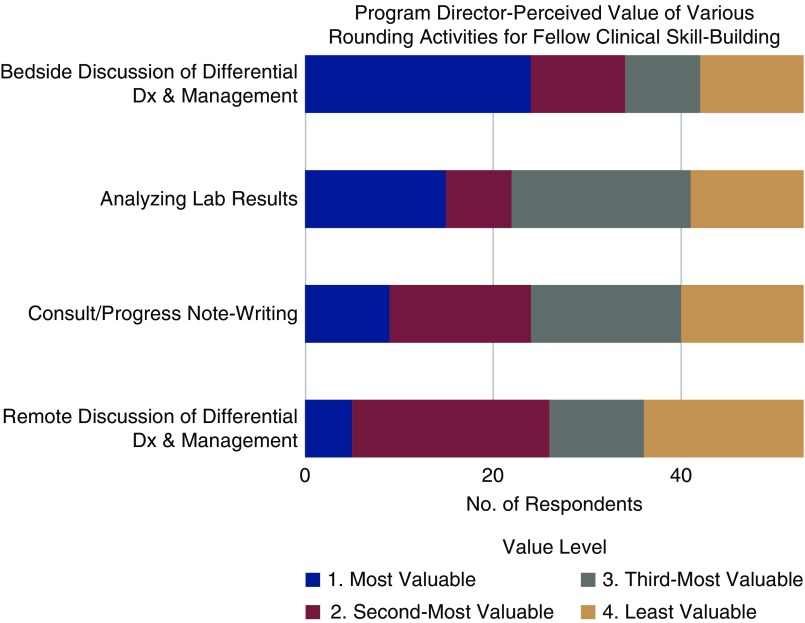

When asked if it were acceptable for fellows to collect patient data without examining patients before attending-rounds, most directors (49%) agreed or strongly agreed. To build a fellow’s clinical skills, directors most valued bedside discussion of differential diagnoses and management plans with the attending on rounds (44%), followed by analysis of laboratory results (27%), formulation of differential diagnoses and plans through writing notes (16%), and discussion of differential diagnoses and management plans with the attending remote to the patient’s bedside (9%). Figure 2 demonstrates how program directors ranked the various activities relative to each other.

Figure 2.

Program director perceptions of the relative importance of different activities for building fellows’ clinical skills. The values 1–4 represent the value of the activity from most (1) to least (4) valuable. The activities are analyzing laboratory results; formulating a differential diagnosis (dx) and management plan through writing consult and progress notes; bedside discussion of differential diagnosis and management plans with the attending; and remote discussion of differential diagnosis and management plans with the attending (for example, in an office).

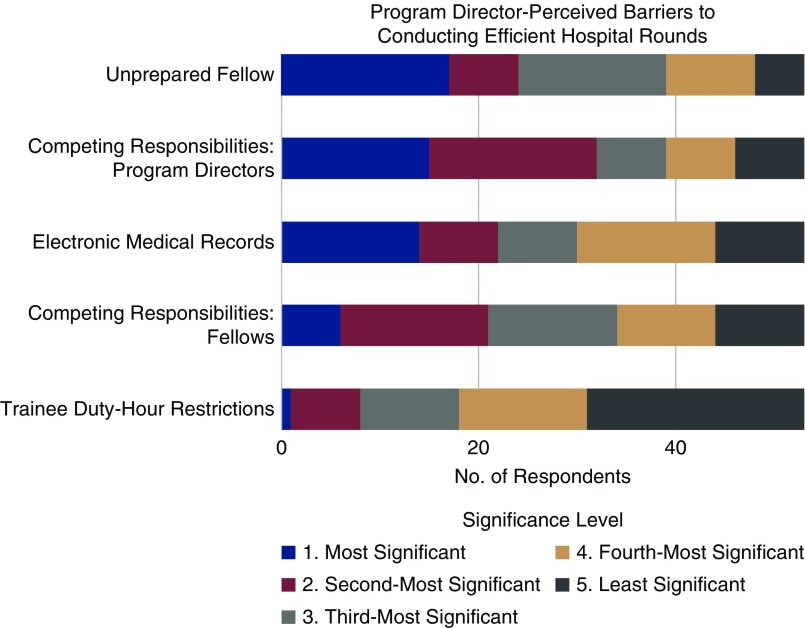

Directors identified fellows’ unpreparedness for clinical demands as the greatest barrier to conducting efficient rounds (31%), followed by competing clinical/administrative responsibilities for faculty and the EMR (both 27%); competing clinical/administrative responsibilities for fellows (14%); and trainee duty-hour restrictions (3%). Figure 3 shows the rank of these barriers relative to each other.

Figure 3.

Program director perceptions of the relative significance of barriers to conducting efficient rounds. The values 1–5 represent barriers to conducting efficient rounds from most (1) to least (5) significant. The barriers are electronic medical records, trainee duty hours, fellows unprepared for the clinical demands of nephrology fellowship, competing clinical and administrative responsibilities for faculty, and competing clinical responsibilities for fellows (for example, outpatient clinic or procedures). One of the 54 respondents ranked only three of the five barriers.

Most agreed or strongly agreed that patient care (71%) and fellows’ clinical skills (84%) improve when fellows independently interview and examine patients at the bedside before attending-rounds. Only 51% agreed or strongly agreed that patient care improves when fellows and attendings interview and examine patients at the bedside together; 21% disagreed or strongly disagreed, and 29% were neutral. Most (84%) rated their rounds as “efficient” or “somewhat efficient.”

Discussion

Our study demonstrates that current United States nephrology fellows care for high volumes of patients on their hospital consult services, while balancing other clinical responsibilities, including outpatient clinics and procedures. Workdays are long; most fellows arrive at the hospital before 7:00 am, and nearly half finish inpatient clinical documentation after 5:00 pm. Program directors complete inpatient documentation late in the day, usually after the traditional workday. Fellows also prepare for attending-rounds differently. Nearly 30% “always” or “most of the time” collect patient data before attending-rounds, without examining patients. This aligns with the 25% of program director respondents who expect fellows to collect patient data before attending-rounds but not to perform bedside examination. Despite variability in the reported frequency of examining patients with the attending, both fellows and program directors highly value bedside rounds for clinical skill-building.

These survey results suggest that nephrology training programs have followed national trends in hospital rounding. But nephrology is unique and requires independent consideration. Nephrology patients are also among the most medically complex (18). Seventy percent of nephrology fellows have more than 15 inpatients on their census; 38%, more than 21. By comparison, the average inpatient census for internal medicine interns is closer to ten (12,13).

Program directors most frequently cited fellows’ unpreparedness for the clinical demands of training programs as a barrier to efficient rounds. A recent ASN-sponsored survey revealed that 88% of program directors remediated at least one fellow in a 5-year period. The most common deficiencies were medical knowledge and organization/efficiency (21). Residency programs’ isolation of inpatient and outpatient responsibilities is a potential source of this unpreparedness. Many use a “4:1 schedule”: 4 weeks of exclusively inpatient service and 1 week of exclusively outpatient clinic (23). In nephrology fellowship, nearly 90% of fellows report outpatient duties, and nearly 50% report procedural duties, simultaneous with hospital rounds. Some nephrology fellows may, therefore, lack the experience required to multitask across clinical domains.

We found that prerounding practices differ across programs, and perspectives vary on the value of activities for patient care and fellows’ clinical skills. In the future, the merits and drawbacks of different rounding models should be systematically studied to develop best-practice standards that consider the balance between service versus education, and fellow autonomy versus attending supervision. For example, a model in which fellows only collect laboratory data before attending-rounds might reduce service hours and provide more bedside supervision by attendings, but deprive fellows of opportunities for independent clinical reasoning, autonomy, and the fulfillment that independent patient interaction can bring. Perceived lack of autonomy and meaningful patient interaction are risk factors for physician burnout (24). By contrast, in the card-flip model, fellows receive less bedside supervision, and possibly more autonomy, but limited opportunities for attendings to model clinical reasoning skills and directly observe the fellow (10). Our questionnaire did not specifically inquire about night-time patient care, but we note that some United States nephrology programs have implemented night-float systems where new consults are completed overnight and signed out to fellows on a day shift. Although this model affords fellows autonomy and prompt patient care, it might decrease opportunity for attending supervision at the bedside. In our study and others, respondents underscored the importance of bedside attending-rounds for both learners and patients (12). Future studies should explore opportunities to incorporate bedside attending-rounds more seamlessly into current workflows.

The high proportion of fellows and program directors reporting late-evening note documentation is concerning. Widespread EMR adoption has increased the time that physicians spend on indirect patient care, which is closely associated with physician burnout (7,8,25–29). Quality improvement initiatives have focused on reducing the documentation burden and improving workflow (30–33). The effect of documentation patterns in the hospital setting is less clear, and to our knowledge, no data link the timing of documentation by medical consultants to patient outcomes (34). Consequently, the documentation practices of nephrologists, as well as the impact of these practices on patient care and the wellness of the workforce, deserve further study. Appropriate application of technology during rounds may streamline patient care and expedite clinical documentation. Although most respondents used technology (commonly, mobile phone applications) during rounds, its use did not significantly associate with time of documentation completion (35,36). Less-utilized technologies, like voice-recognition software, offer possible solutions (16). Formal coaching programs targeting EMR use and fellows’ organizational skills could also improve efficiency without compromising quality.

This study has limitations. Our ability to use only a finite number of questions narrowed the scope of the surveys. We were unable to obtain demographics for individual program director respondents, which might have influenced survey responses. Although attendees at the Nephrology Training Program Directors’ Retreat came from a broad range of program sizes and 70% of states in the United States, only 47% of all programs were represented, generating potential selection bias. Differences in scales for fellows and program directors limited our ability to compare responses within similar domains. The questionnaire was also unable to capture details related to EMR type, roles of advanced practitioners and other learners, and the characteristics of patients on the hospital service, which could affect workflow. Although the questionnaire addressed prerounding practices and other aspects of workflow, it did not include specific rounding models, such as card-flip or discovery, because attending nephrologists in a single program might prefer multiple rounding models, and not all fellows or directors know the names for such models. Although the fellow questionnaire sought the average daily census for a typical weekday on the inpatient consult service, “daily” was inadvertently omitted from the question. This might have led to response bias, with some mistaking it for a weekly census and overestimating the number. Participation bias and respondent recall bias are also possible. There was <4% question nonresponse in a largely even distribution across questions, but we could not determine if this was random, or related to difficulty with question interpretation, or respondent fatigue. Data from this survey is only generalizable to adult United States nephrology fellows and program directors. However, this study is large, nationally representative, and, to our knowledge, the first to provide insight about the general structure of hospital rounds in United States nephrology training programs, and a framework for future initiatives to improve fellows’ clinical experience and patient care.

In conclusion, this survey study is the first to describe perceptions of hospital rounds at United States nephrology training programs. It identifies the following areas for future investigation: (1) the effect of clinical documentation burden on nephrologist wellness and patient outcomes; (2) how technology, novel workflows, and formal coaching programs might influence documentation practices; (3) the effect of specific rounding models, including card-flip, discovery, night float, and hybrid versions, on fellows’ core-competencies achievement, wellness, and patient outcomes; and (4) early identification of attributes of struggling fellows and development of curricula and coaching programs to remediate deficits like clinical reasoning and organizational skills.

Disclosures

Dr. Baynes-Fields, Dr. Boyle, Dr. Goldman, Dr. Harhay, Mr. Pivert, Mr. Subedi, and Dr. Warburton have nothing to disclose.

Funding

Dr. Harhay is supported by National Institutes of Health, National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grant K23DK105207, and a Commonwealth Universal Research Enhancement award, outside of the submitted work.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Mr. Pivert is an employee of the ASN Alliance for Kidney Health.

The authors thank Stephen M. Sozio, MHS, MEHP, and members of the American Society of Nephrology’s Workforce and Training Committee for their input and facilitating distribution of the surveys.

Footnotes

Published online ahead of print. Publication date available at www.cjasn.org.

Supplemental Material

This article contains the following supplemental material online at http://cjasn.asnjournals.org/lookup/suppl/doi:10.2215/CJN.10190819/-/DCSupplemental.

Supplemental Appendix 1. Fellows survey.

Supplemental Table 1. Association of objective workload with workflow domains.

Supplemental Table 2. Effect of the size of the fellowship training program, patient census per fellow, and technology use on time at completion of progress notes: Results from the multinomial logistic regression model.

References

- 1.Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education ACGME Common Program Requirements (Fellowship), 2018. Available at: https://www.acgme.org/Portals/0/PFAssets/ProgramRequirements/CPRFellowship2019.pdf. Accessed July 15, 2019

- 2.Rabinowitz R, Farnan J, Hulland O, Kearns L, Long M, Monash B, Bhansali P, Fromme HB: Rounds today: A qualitative study of internal medicine and pediatrics resident perceptions. J Grad Med Educ 8: 523–531, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Block L, Habicht R, Wu AW, Desai SV, Wang K, Silva KN, Niessen T, Oliver N, Feldman L: In the wake of the 2003 and 2011 duty hours regulations, how do internal medicine interns spend their time? J Gen Intern Med 28: 1042–1047, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Wenger N, Méan M, Castioni J, Marques-Vidal P, Waeber G, Garnier A: Allocation of internal medicine resident time in a swiss hospital: A time and motion study of day and evening shifts. Ann Intern Med 166: 579–586, 2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mamykina L, Vawdrey DK, Hripcsak G: How do residents spend their shift time? A time and motion study with a particular focus on the use of computers. Acad Med 91: 827–832, 2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Chaiyachati KH, Shea JA, Asch DA, Liu M, Bellini LM, Dine CJ, Sternberg AL, Gitelman Y, Yeager AM, Asch JM, Desai SV: Assessment of inpatient time allocation among first-year internal medicine residents using time-motion observations. JAMA Intern Med 179: 760–767, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Babbott S, Manwell LB, Brown R, Montague E, Williams E, Schwartz M, Hess E, Linzer M: Electronic medical records and physician stress in primary care: Results from the MEMO Study. J Am Med Inform Assoc 21: e100–e106, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Tai-Seale M, Dillon EC, Yang Y, Nordgren R, Steinberg RL, Nauenberg T, Lee TC, Meehan A, Li J, Chan AS, Frosch DL: Physicians’ well-being linked to in-basket messages generated by algorithms in electronic health records. Health Aff (Millwood) 38: 1073–1078, 2019 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Rathert C, Williams ES, Linhart H: Evidence for the quadruple aim: A systematic review of the literature on physician burnout and patient outcomes. Med Care 56: 976–984, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shoeb M, Khanna R, Fang M, Sharpe B, Finn K, Ranji S, Monash B: Internal medicine rounding practices and the Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education core competencies. J Hosp Med 9: 239–243, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zhang E: Let’s change rounds. Op-Med 2018. Available at: https://opmed.doximity.com/articles/let-s-change-the-rounds-runaround-570f4477-3f5c-4e16-b3b1-554797fa6755?_csrf_attempted=yes. Accessed July 15, 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gonzalo J: The return of bedside rounds. J Gen Intern Med 26: 114, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.McMahon GT, Katz JT, Thorndike ME, Levy BD, Loscalzo J: Evaluation of a redesign initiative in an internal-medicine residency. N Engl J Med 362: 1304–1311, 2010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Priest JR, Bereknyei S, Hooper K, Braddock CH 3rd: Relationships of the location and content of rounds to specialty, institution, patient-census, and team size. PLoS One 5: e11246, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sandhu AK, Amin HJ, McLaughlin K, Lockyer J: Leading educationally effective family-centered bedside rounds. J Grad Med Educ 5: 594–599, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Calderon AS, Blackmore CC, Williams BL, Chawla KP, Nelson-Peterson DL, Ingraham MD, Smith DL, Kaplan GS: Transforming ward rounds through rounding-in-flow. J Grad Med Educ 6: 750–755, 2014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Seigel J, Whalen L, Burgess E, Joyner BL Jr, Purdy A, Saunders R, Thompson L, Yip T, Willis TS: Successful implementation of standardized multidisciplinary bedside rounds, including daily goals, in a pediatric ICU. Jt Comm J Qual Patient Saf 40: 83–90, 2014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tonelli M, Wiebe N, Manns BJ, Klarenbach SW, James MT, Ravani P, Pannu N, Himmelfarb J, Hemmelgarn BR: Comparison of the complexity of patients seen by different medical subspecialists in a universal health care system. JAMA Netw Open 1: e184852, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Melamed ML, Campbell KN, Nickolas TL: Resizing nephrology training programs: A call to action. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 12: 1718–1720, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lane CA, Brown MA: Nephrology: A specialty in need of resuscitation? Kidney Int 76: 594–596, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Warburton KM, Mahan JD: Coaching nephrology trainees who struggle with clinical performance. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 172–174, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roberts JK: Burnout in nephrology: Implications on recruitment and the workforce. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol 13: 328–330, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mariotti JL, Shalaby M, Fitzgibbons JP: The 4∶1 schedule: A novel template for internal medicine residencies. J Grad Med Educ 2: 541–547, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Djulbegovic M, Beckstead JW, Fraenkel L: The patient care ownership scale: Development of an instrument to measure patient care ownership among internal medicine trainees. J Gen Intern Med 34: 1530–1537, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Joukes E, Abu-Hanna A, Cornet R, de Keizer NF: Time spent on dedicated patient care and documentation tasks before and after the introduction of a structured and standardized electronic health record. Appl Clin Inform 9: 46–53, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baumann LA, Baker J, Elshaug AG: The impact of electronic health record systems on clinical documentation times: A systematic review. Health Policy 122: 827–836, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Arndt BG, Beasley JW, Watkinson MD, Temte JL, Tuan WJ, Sinsky CA, Gilchrist VJ: Tethered to the EHR: Primary care physician workload assessment using EHR event log data and time-motion observations. Ann Fam Med 15: 419–426, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Tran B, Lenhart A, Ross R, Dorr DA: Burnout and EHR use among academic primary care physicians with varied clinical workloads. AMIA Jt Summits Transl Sci Proc 2019: 136–144, 2019 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Downing NL, Bates DW, Longhurst CA: Physician burnout in the electronic health record era: Are we ignoring the real cause? Ann Intern Med 169: 50–51, 2018 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Robinson KE, Kersey JA: Novel electronic health record (EHR) education intervention in large healthcare organization improves quality, efficiency, time, and impact on burnout. Medicine (Baltimore) 97: e12319, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Grando A, Manataki A, Furniss SK, Duncan B, Solomon A, Kaufman D, Hirn S, Sunday R, Bouchereau J, Doebbeling B, Burton MM, Poterack KA, Miksch T, Helmers RA: Multi-method study of electronic health records workflows. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2018: 498–507, 2018 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Pugh CM: Electronic health records, physician workflows and system change: Defining a pathway to better healthcare. Ann Transl Med 7[Suppl 1]: S27, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Ramaiah M, Subrahmanian E, Sriram RD, Lide BB: Workflow and electronic health records in small medical practices. Perspect Health Inf Manag 9: 1d, 2012 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Christino MA, Matson AP, Fischer SA, Reinert SE, Digiovanni CW, Fadale PD: Paperwork versus patient care: A nationwide survey of residents’ perceptions of clinical documentation requirements and patient care. J Grad Med Educ 5: 600–604, 2013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kumah-Crystal YA, Pirtle CJ, Whyte HM, Goode ES, Anders SH, Lehmann CU: Electronic health record interactions through voice: A review. Appl Clin Inform 9: 541–552, 2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Walsh C, Stetson P: EHR on the move: Resident physician perceptions of iPads and the clinical workflow. AMIA Annu Symp Proc 2012: 1422–1430, 2012 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.