Abstract

Background: Dry powder inhalers (DPIs) offer a number of advantages, such as rapid delivery of high-dose inhaled medications; however, DPI use in children is often avoided due to low lung delivery efficiency and difficulty in operating the device. The objective of this study was to develop a high-efficiency inline DPI for administering aerosol therapy to children with the option of using either an oral or trans-nasal approach.

Methods: An inline DPI was developed that consisted of hollow inlet and outlet capillaries, a powder chamber, and a nasal or oral interface. A ventilation bag or compressed air was used to actuate the device and simultaneously provide a full deep inspiration consistent with a 5-year-old child. The powder chamber was partially filled with a model spray-dried excipient enhanced growth powder formulation with a mass of 10 mg. Device aerosolization was characterized with cascade impaction, and aerosol transmissions through oral and nasal in vitro models were assessed.

Results: Best device performance was achieved when all actuation air passed through the powder chamber (no bypass flow) resulting in an aerosol mean mass median aerodynamic diameter (MMAD) <1.75 μm and a fine particle fraction (<5 μm) ≥90% based on emitted dose. Actuation with the ventilation bag enabled lung delivery efficiency through the nasal and oral interfaces to a tracheal filter of 60% or greater, based on loaded dose. In both oral and nose-to-lung (N2L) administrations, extrathoracic depositional losses were <10%.

Conclusion: In conclusion, this study has proposed and initially developed an efficient inline DPI for delivering spray-dried formulations to children using positive pressure operation. Actuation of the device with positive pressure enabled effective N2L aerosol administration with a DPI, which may be beneficial for subjects who are too young to use a mouthpiece or to simultaneously treat the nasal and lung airways of older children.

Keywords: 3D printing, active DPI, aerosol delivery to children, inline DPI, in vitro testing, spray-dried powder

Introduction

In contrast with typical inhalation-driven dry powder inhalers (DPIs), inline devices are actuated by an external gas source, such as a ventilation bag, air-filled syringe, or compressed air.(1–4) A primary advantage of this approach is that the actuation air volume and flow rate can be controlled and reproduced with low variability. Based on the use of an external source of actuation air, inline devices may be effective for the delivery of powder aerosols to infants and children who are too young to operate a conventional passive DPI.(5–7) These devices may also be beneficial for delivering powder-based aerosols to subjects with compromised lung function or during different forms of ventilation including noninvasive ventilation with a mask(8) or nasal prongs,(9,10) and conventional ventilation through an endotracheal tube.(4,11) Previous studies have also demonstrated that inline DPIs are capable of delivering relatively high powder mass,(4,6,12) which is beneficial for rapid administration of inhaled antibiotics, osmotic agents to enhance clearance, lung surfactant, and some new anti-inflammatory medications.

In the administration of pharmaceutical aerosols to children, delivery efficiency of the aerosol to the lungs is expected to be low(13,14) and highly variable.(15) Considering nebulized aerosol, El Taoum et al.(16) reported lung doses of 0%–3% of nebulized drug in an anatomically realistic nasal cavity model of a 5-year-old child that included cyclic respiration and a variety of patient interfaces. Other benchtop testing studies that have considered nebulized aerosol delivery with a mask interface have also reported ∼10% or less lung delivery efficiency.(17,18) Ari et al.(19) considered trans-nasal aerosol delivery with a nasal cannula interface (without a nasal model) and also reported lung delivery efficiency of ∼10% and below.

Children can often use a passive DPI by an age of ∼5 years old.(14,20,21) Below et al.(13) evaluated aerosol delivery efficiency through a representative mouth–throat (MT) model of a 4- to 5-year-old child for the Salbulin Novolizer® and SalbuHexal Easyhaler® inhalers, which are licensed for use by children in Europe. When operated with a realistic breathing pediatric waveform, the Novolizer and Easyhaler delivered ∼5% and 22% of the nominal dose to a tracheal filter, respectively. Similar results with lung delivery efficiency of 10% and below were also observed for three additional commercial products using identical methods.(22) In contrast with oral inhalation, nose-to-lung (N2L) aerosol administration of a powder-based aerosol in children older than 1 year has not been previously reported, of which we are aware. For N2L delivery in a 9-month-old infant in vitro nasal model using the Solovent inline DPI device, Laube et al.(5) reported that <4% of the emitted dose (ED) reached a tracheal filter.

While efficient aerosol delivery is important, especially for medications with narrow therapeutic windows, multiple studies(14,20,21,23,24) stress the equally important need for patients to be able to use inhalers correctly (or effectively) leading to device compliance. A number of studies have shown that ∼60% or less of adult patients, physicians, nurses, and pharmacists do not know how to effectively operate an inhaler.(20,23–26) Hence, pediatric inhalers should be as user-friendly as possible, and it may be necessary for a child to receive assistance in using the inhaler from an adult caregiver. Lexmond et al.(27) evaluated the use of DPIs by children within an age range of ∼5–12 years using a measurement device with a variety of possible mouthpieces (MP) and resistances. Based on these in vivo measurements, it was determined that pediatric inhalers should empty effectively with an inhaled volume of 0.5 L and a peak inspiratory flow rate of 25–40 L/min (LPM).(27) Using an identical approach, Lexmond et al.(28) included children with cystic fibrosis (CF) and further reduced the recommended peak inspiratory flow rate to 20–30 LPM.(28) Passive DPIs typically cannot achieve this performance, except for perhaps the Simoon device operated with a spray-dried formulation and reported nominal fill mass of 1 or 2 mg.(29) Surprisingly, Lexmond et al.(27) observed that 90% of inhalations were associated with oral obstruction, arising from the tongue or cheeks, which may limit aerosol delivery beyond what is observed with rigid in vitro models. These events likely occur more often in pediatric subjects due to reduced muscle and pharyngeal tone during the negative pressure maneuver required to operate a passive DPI. Furthermore, between 10% and 44% of trained pediatric subjects exhaled into the measurement device.(27)

In the current study, a pediatric inline DPI is proposed with the intent of improving aerosol lung delivery efficiency (above the current standard of 5%–10%) as well as better enabling effective use by children. To improve delivery efficiency with DPIs, previous studies on adult inhalers have employed a combination of highly dispersible spray-dried formulations, computational fluid dynamics (CFD) simulations, and device engineering to produce excellent aerosolization and lung delivery characteristics.(1,12,30,31) Considering effective use of the device, operating with a positive pressure gas source provides multiple advantages. First, the gas source enables targeted and reproducible actuation. This may overcome problems associated with the high variability in pediatric inhalation described by Devadason.(21) Second, positive pressure gas delivery enables flexibility for oral or N2L aerosol administration. Third, the gas source provides the aerosol with positive pressure (as opposed to negative pressure with passive DPIs), which is expected to expand the upper airways and potentially reduce the oral obstructions observed by Lexmond et al.(27) Finally, a positive pressure device will resist exhalation flow through the inhaler, thereby preventing degradation of the powder from the high humidity in exhaled breath, and can be used to help maintain a breath-hold if desired.

Children younger than 3 or 4 years typically cannot form a seal to use an inhaler MP.(21,23) Lexmond et al.(27) observed that at 5 years of age, half of the study participants could operate a DPI and the other half could not. At 6 years of age, most could execute a correct DPI inhalation maneuver.(27) At any age, there are likely advantages to simultaneously treating the nasal passage and remaining airways in multiple clinical indications. For example, in asthma, it is often held that airway hyperresponsiveness affects the lungs and the nose and that treatment of nasal conditions such as rhinitis with inhaled corticosteroids improves asthma control.(32,33) In CF, the nose may be viewed as a potential harbor for bacteria that can infect or reinfect the lungs, potentially leading to airway colonization with Pseudomonas aeruginosa.(34–36) While treatment of the nasal and lung airways is not needed in every case, it may prove to be a beneficial option for physicians and respiratory therapists to have available. Indeed, some pediatricians prefer to prescribe nebulized aerosols and a face mask to children older than 6 years to simultaneously treat the nose and lungs during an asthma exacerbation, potentially instigated by rhinitis.

Initial inline DPI systems produced high device drug losses and poor lung delivery efficiency.(5,7,37) However, significant progress has been made recently through the use of highly dispersible spray-dried formulations,(38,39) CFD simulations,(30,40) and device engineering.(1,12) Behara et al.(2) developed an inline capsule-based DPI that contained a flow control orifice and three-dimensional (3D) rod array to maximize powder deaggregation. When operated with a 1 L ventilation bag, best case devices produced an ED of 70%–75% and aerosol mass median aerodynamic diameter (MMAD) range of 1.4–1.6 μm depending on the size of the flow control orifice and 3D rod array configuration. For operation with low air volumes (LV), Farkas et al.(1) developed an inline DPI that employed hollow metal capillaries to both pierce the capsule and form a continuous aerosolization flow pathway through the device. When operated with 10 mL pulses of air over five actuations with a spray-dried excipient enhanced growth (EEG) powder formulation, device ED was as high as 85% with an MMAD of ∼2 μm. In subsequent studies, the LV-DPI was integrated into a low-flow nasal cannula delivery system.(12,31) Primary advantages of the LV-DPI compared with the 3D rod array system were more efficient aerosolization as well as easier device loading and capsule piercing in a positive pressure device. While these results are promising, the hollow capillary-based DPIs have not been tested with significantly higher air volumes and flow rates. Flow rates that are too high may aerosolize the powder too quickly and degrade aerosolization performance.(30) Previous studies have indicated that optimal performance of the device occurs when the powder bed is not directly contacted by the incoming air jet.(1,30) Open questions in transitioning the capillary-based DPI to a high-flow system include whether all the airflow should be passed through the capsule or if some bypass air should be used. It is also unknown if the outlet air jet will cause excess deposition in the patient interface or extrathoracic airways. Finally, efficient transmission of the aerosol through the device and extrathoracic airways needs to be proven.

The objective of this study was to develop a high-efficiency inline DPI for administering aerosol therapy to children using a positive pressure air source with the option of using either an oral or a trans-nasal approach. The inline DPI will deliver both aerosol and a full pediatric inhalation air volume, with the intent of providing controlled and repeatable use of the device. An EEG formulation using albuterol sulfate (AS) as the model drug will be tested with a 10 mg initial powder mass. As described previously, EEG aerosol delivery implements a small initial aerosol size to minimize extrathoracic depositional loss.(10,41,42) The hygroscopic excipient within each particle causes the aerosol size to increase within the airways, thereby enhancing aerosol deposition, reducing exhalation loss of the initially small particle aerosol, and potentially targeting deposition within specific lung regions.(10,41–46) In future applications, the powder mass may be increased for delivering high-dose medications, such as inhaled antibiotics, or decreased for delivering low-dose therapies, such as inhaled corticosteroids. Aerosolization characteristics are initially tested for multiple designs with and without bypass air and with different sizes of inlet and outlet capillaries. Nasal cannula design is then optimized for N2L delivery in a 5-year-old in vitro geometry. Finally, aerosol delivery to a tracheal filter is tested for oral and nasal administration. Device performance targets include an ED >85% of the loaded dose, a mean MMAD <1.75 μm (and preferably ≤1.5 μm), as well as fine particle fraction (FPF) of ED <5 μm (FPF<5μm/ED) >90%, and FPF<1μm/ED >20%. This initially small particle aerosol is expected to have low extrathoracic depositional loss(10,38,44) and achieve sufficient size increase within the airways to enhance lung retention.(10,41) In this initial proof of concept study, tracheal filter delivery targets are ≥60% for oral or nasal administration. Extrathoracic deposition should be approximately <10% and preferably <5% of the loaded dose.

Materials and Methods

Materials and powder formulation

Albuterol sulfate (AS) United States Pharmacopeia (USP) was purchased from Spectrum Chemicals (Gardena, CA), and Pearlitol® PF-Mannitol was donated from Roquette Pharma (Lestrem, France). Poloxamer 188 (Lutrol F68) was donated from BASF Corporation (Florham Park, NJ). l-Leucine and all other reagents were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO). Quali-V hydroxypropyl methylcellulose capsules (size 0) were donated from Qualicaps (Whitsett, NC).

Multiple batches of a spray-dried AS EEG powder formulation were produced based on the optimized method described by Son et al.(38,39) using a Büchi Nano Spray Dryer B-90HP (Büchi Laboratory-Techniques, Flawil, Switzerland). The EEG powder formulation contained a 30:48:20:2% w/w ratio of AS, mannitol, l-leucine, and Poloxamer 188.

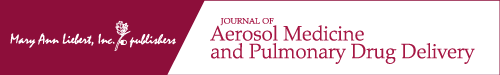

Device designs

Based on initial experiments, it was established that a positive pressure of 6 kPa could reasonably be generated by a 1 L ventilation bag using firm compression with one hand. As described later, reasonable positive pressure airflow delivery conditions for a 5-year-old child were assumed to be a 750 mL inhalation volume and flow rate of ∼15 LPM, resulting in a 3-second delivery period. The base inline pediatric DPI was consistent with the LV-DPI designs developed by Farkas et al.,(1,12,31) but with approximately one order of magnitude more air volume. The increased air volume and lower available actuation pressure required that the inlet and outlet capillaries be larger. Capillary dimensions to provide the approximate flow rate at the actuation pressure of 6 kPa were estimated using analytical resistance versus flow rate relationships. In device Cases 1 and 2 (Fig. 1a), the effect of some bypass air passing around the powder chamber was considered. Cases 3 and 4 (Fig. 1b) passed all the available airflow through the powder chamber, which required larger capillaries to provide the approximate flow rate of 15 LPM at 6 kPa. Previous studies have illustrated that a smaller inlet versus outlet capillary can also improve aerosolization performance, based on increasing secondary flows arising from compressible flow effects.(30) Different outlet diameters were therefore considered for both the bypass and single-stream designs.

FIG. 1.

Axial cross-sectional views of the pediatric inline DPIs (a) with bypass airflow and (b) without bypass airflow. Sharpened hollow capillaries pierce the capsule and provide a continuous airflow pathway through the powder chamber when the device is closed. The bypass design includes flow pathways that direct some air, based on flow path resistance, around the powder chamber. DPI, dry powder inhaler.

Cases 1 and 2 with bypass flow were designed to deliver a similar flow rate through the powder chamber as the previous LV-DPI (∼3 LPM), but over a longer period of time (3 vs. 0.2 seconds). To deliver 750 mL in 3 seconds, some flow was diverted to an array of four 0.76 mm capillaries that allowed air to pass around the powder chamber, but still exit to the same outlet as the aerosol, that is, bypass flow. Case 1 used inlet and outlet capillary diameters of 1.52 mm, whereas Case 2 used an inlet diameter of 1.4 mm and an outlet diameter of 1.8 mm.

Designs of Cases 3 and 4 were very similar to the LV-DPI from our previous studies as they contain a single inlet capillary and a single outlet capillary forming a straight-through flow pathway. This allowed all the air to pass through the powder chamber to assist in aerosol formation. Case 3 consisted of inlet and outlet capillary diameters of 2.39 mm, and Case 4 used an inlet diameter of 1.83 mm and an outlet diameter of 2.39 mm.

As with previous hollow capillary inline DPIs,(1) the inlet and outlet capillaries were sharpened and recessed within the device. To operate the inhaler, a capsule is loaded with the powder formulation and placed between the inlet and outlet device halves. The halves are then closed and locked together with a twisting motion, which both pierces the capsule and forms a continuous airtight flow pathway with one step. Actuation of the device with a positive pressure causes a high-speed jet of air to enter the powder chamber initially deaggregating the powder and forming an initial aerosol. Once formed, it is expected that the aerosol is further deaggregated within the powder chamber and as it exits the outlet capillary through interactions with shear flow and turbulent eddies.(30) Compressible flow effects associated with flow deceleration and acceleration as well as small geometric asymmetries create secondary flows that contribute to aerosol formation and emptying of the powder chamber.(30) It was previously determined that best aerosolization occurs when the inlet air jet does not directly impact the powder bed and the secondary velocities are instead used to form the initial aerosol. It was expected that this approach slows the process of aerosolization providing a longer time period for deaggregation forces to act and potentially avoiding reaggregation or two-way coupled momentum effects.(30)

The inline DPIs, as well as the streamlined (SL) nasal cannulas and MP described in the next section, were created using Autodesk Inventor and exported as .STL files to be prototyped. The inline DPI files were then prepared using the Objet Studio preparation software and were built using an in-house Stratasys Objet24 3D Printer (Stratasys Ltd., Eden Prairie, MN) using VeroWhitePlus material at a 32 μm resolution. Support material was cleaned away from the model material using a Stratasys water-jet cleaning station and the devices were allowed to fully dry before use. To improve interior surface smoothness, the SL nasal cannulas and MPs were built using stereolithography (SLA) in Accura ClearVue by 3D Systems On Demand Manufacturing (3D Systems, Inc., Rock Hill, SC). The capillaries used in the inline DPIs were custom cut from lengths of stainless steel (SAE 304) capillary tubing and were sharpened to allow for easy piercing of the capsule upon insertion. O-rings were used as needed to ensure that all components were joined with airtight seals that could withstand the expected operating pressures.

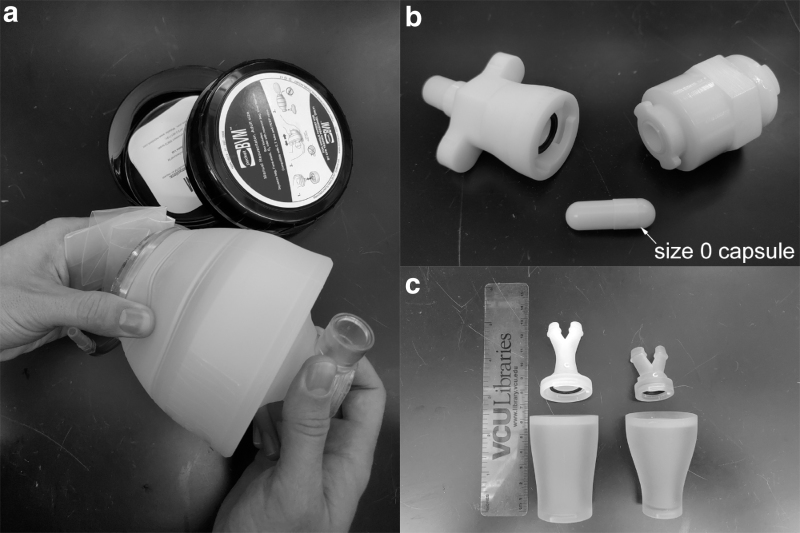

Cannula designs

Two primary cannula designs were evaluated (Cannula 1 vs. Cannula 2) as well as two outlet versions of Cannula 2 (Cannula 2a vs. 2b). In all cases, the cannulas connected directly to the aerosol outlet of the inline DPIs, as shown in Figure 1. Outlet prong sizes were also the same in all cases with elliptical outlets characterized by major and minor diameters of 10.5 mm and 5.5 mm, respectively. Exterior cones on the prongs were used to help form an airtight seal with the interior nostril surface when inserted ∼5 mm into the nose. The Cannula 1 design (Fig. 2a) started with an inlet diameter of 15 mm consistent with the initial outlet of the inline DPI. This diameter was gradually tapered to a smaller diameter of 9.7 mm over a length of 20 mm before a constant cross-sectional area was maintained through the bifurcation region. In contrast, with Cannula 2a, the inline DPI was remade with an outlet diameter of 9.7 mm. This enabled a shorter cannula geometry that maintained a constant cross-sectional area throughout the bifurcation region (Fig. 2b). External images of Cannulas 2a and 2b are shown in Figure 2c and d. As shown in these figures, Cannula 2a had outlet prongs that were truncated on a plane parallel with the inlet, whereas Cannula 2b turned the prong outlets inward 15 degrees toward the nasal septum.

FIG. 2.

Nasal cannula interfaces for N2L or trans-nasal aerosol administration including cross-sectional views of (a) Cannula 1 and (b) Cannula 2a, and exterior surface renderings of (c) Cannula 2a and (d) Cannula 2b. Cones on the exterior surface of the prongs were used to form an airtight seal when the cannula was inserted a short distance (∼5 mm) into the nostrils. N2L, nose-to-lung.

MP designs

Two MP designs were also tested to assess delivery performance of the inline DPI in an oral delivery scenario. MP 1 (Fig. 3a), like Cannula 1, was designed to connect to the larger 15 mm diameter outlet device. The cross section was transitioned to the size of the MT inlet over a length of 50 mm. A flange on the end of the MP was made to overlap the outer diameter of the MT inlet to provide an airtight seal. MP 2 (Fig. 3b) was the same design as MP 1, with the exception of the connection to the inline DPI. Similar to Cannula 2, MP 2 was designed to connect to the 9.7 mm diameter device outlet and then transition to the same outlet design as MP 1.

FIG. 3.

Cross-sectional views of (a) MP 1 with a 15 mm diameter inlet and (b) MP 2 with a 9.7 mm diameter inlet. The left-hand side of the MPs connects to the inline DPI and the right-hand side forms a smooth connection with the MT model. MP, mouthpiece; MT, mouth–throat.

Airway models and inhalation conditions

To test aerosol delivery through the extrathoracic airway and to the lungs, representative models of the nasal airways and MT airways for a 5-year-old were developed and built using 3D printing (SLA) in Accura ClearVue resin (3D Systems). The nasal and MT models were constructed and tested separately, such that trans-nasal administration assumed that the mouth was held closed and oral administration assumed that the child inhaled consistent with the delivered airflow or that the nose was held closed. Considering the nasal model, the realistic pediatric nose–throat (NT) geometry from the RDD Online website (www.rddonline.com) was selected. This geometry originated from a CT scan of a 5-year-old female child. As shown in Figure 4a, the geometry extended from the nostrils through approximately the middle of the trachea, and the internal geometry of the pediatric NT geometry was not altered. In this study, the exterior shell structure (Fig. 4b) was altered to allow for connection to the Next Generation Impactor (NGI). Positive pressure delivery of the aerosol was also found to force air into the junction between the anterior nose and middle passage. To prevent this from occurring, an airtight twist lock and double o-ring seal were also added to the pediatric NT geometry.

FIG. 4.

Pediatric airway models of a 5-year-old showing (a) inner airway surfaces of the NT from nostrils through mid-trachea, (b) outer NT surface model used for 3D printing the geometry, (c) inner airway surfaces of the MT from the mouth through mid-trachea, and (d) outer MT surface model used for 3D printing the geometry. NT, nose–throat.

It is currently unknown if the pediatric NT geometry will match average nasal deposition conditions for a population of 5-year-old children. Geometric characteristics of the internal nasal passages include a total volume (V) of 22.0 cm3 (remeasured from produced model), a surface area (As) of 157.8 cm2, and a total length (L) of 17.1 cm from the nasal inlet through the outlet. Nostril major and minor axes were 12.4 mm and 5.6 mm on the left, and 12.4 mm and 5.7 mm on the right, respectively. For comparison, average dimensions for the 4- to 6-year-old cohort of Golshahi et al.(47) (seven subject subset) include a volume of 22.0 cm3, a surface area of 152.8 cm2, and a total length of 19.1 cm. Relative differences between the pediatric NT geometry and average dimensions of the Golshahi et al.(47) 4- to 6-year-old data are 0.0% for volume, 3.2% for surface area, and 11.0% for length. Golshahi et al.(47) showed that the best characteristic length scale for deposition in pediatric nasal models was . Hence, it is expected that the pediatric NT geometry will provide deposition data that are a reasonable estimate of mean conditions for a 5-year-old child.

Considering a pediatric oral airway model, the idealized MT geometry proposed by Golshahi and Finlay(48) is based on an anatomical data set for 6- to 14-year-olds and therefore likely too large to represent 5-year-old conditions. The RDD Online idealized pediatric MT model is for a 5-year-old; however, the reported model volume of 50.2 cm3 appears more consistent with adult airways.(49) As an alternative geometry, we elected to employ a scaled model of the VCU MT geometry.(49,50) A scaling factor of 0.75 was selected to match the model tracheal outlet diameter to a value of 1.2 cm, which is an approximation of a 5- to 6-year-old child, based on the correlation of Phalen et al.(51) The pediatric MT oral opening was defined to be a 1.7 by 2.2 cm ellipse. The resulting pediatric MT model volume and surface area through the upper tracheal region were 26.2 cm3 and 63.9 cm2, respectively. The interior airway surface and shell geometry of the pediatric MT model are shown in Figure 4c and d. For comparison, distance from the MT inlet to the vertical pharynx midline was 54 mm, which is smaller than with the Golshahi and Finlay(48) pediatric MT model (62.7 mm) and the Wachtel et al.(52) data (58.4 mm; adjusted to the midline of the pharynx) and associated pediatric MT geometry.(13) Cheng et al.(53,54) showed that MT deposition correlates with minimal glottic diameter, which was also supported by Xi and Longest.(55) The pediatric MT model had a minimum glottic diameter of 6.3 mm compared with a value of ∼6.2 mm in the Golshahi and Finlay(48) pediatric MT model. As a result, it is expected that pediatric MT deposition will be similar to other pediatric airway geometries.

Consistent with inhaler testing in adults, the baseline inhaled volume was taken to be 75% of vital capacity, which for a healthy 5-year-old is 1 L,(56) resulting in a delivered air volume of 750 mL. An inhaled air volume greater than the 500 mL limit suggested by Lexmond et al.(27) was viewed as acceptable considering that it was delivered with positive pressure and not as a result of the child's effort breathing against a resistance. The air delivery flow rate was determined as a balance between being sufficiently high enough so that the child is not connected to the device for too long and being sufficiently low enough to minimize device and extrathoracic impaction depositional loss. As a first estimate, a flow rate of 15 LPM (250 cm3/s) was selected, which requires ∼3 seconds to administer the 750 mL inhaled volume. This flow rate is well within the range of comfortable inhalation flows for a 5-year-old and falls between typical tracheal flow rates at rest (∼10 LPM) and during light exercise (∼20 LPM).(27) Furthermore, doubling or halving the specified flow rate of 15 LPM should both be acceptable. Importantly, the inline DPI is operated with a single actuation.

In this study, to establish baseline device operation with the least amount of variability, device aerosolization was initially tested using a compressed air gas source and solenoid valve to generate a square airflow waveform over an approximate 3-second period. For delivery through the extrathoracic airway models, device operation was then tested with a 1 L ventilation bag. The bag was operated with one hand (expected 750 mL delivered air volume) and steady pressure with the goal of compressing the bag over 3 seconds. Comparisons of compressed air versus ventilation bag operation are presented in the Results section.

Powder evaluation

The primary particle size of the spray-dried powder was initially determined using a laser diffraction method with a Sympatec ASPIROS dry dispersing unit and HELOS laser diffraction sensor (Sympatec GmbH, Clausthal-Zellerfeld, Germany). A pressure drop of 4 bar (400 kPa) was used to disperse a small amount of powder for analysis. The geometric diameters given by the laser diffraction system were converted to aerodynamic diameters using the theoretical particle density of 1.393 g/cm3, resulting in an average MMAD of 1.18 μm. This shows that the powder formulation is highly dispersible, when using a benchtop dispersion unit that operates at high pressures (∼2 orders of magnitude above the 6 kPa of the pediatric inline DPI).

Evaluation of DPI performance, interface devices, and lung delivery efficiency

Each experiment in this study was performed using 10 mg of EEG-AS powder formulation, which was manually weighed and placed in size 0 capsules. Loaded capsules were placed in one half of the DAC device, then pierced when the second half was attached, locked, and sealed together with a 30° turn to create the powder chamber. After device assembly, the 10 mg powder mass filled 3% of the chamber volume. It was estimated that the chamber can hold 100 mg without powder contacting the capillaries when the device is operated in the horizontal position. Once loaded, the device was attached to a compressed air line (or ventilation bag) and actuated once using 750 mL of air.

Separate sets of experiments were used to evaluate DPI aerosolization, performance of the interface devices (nasal cannula and MP), and in vitro lung delivery efficiencies. Best performing components were selected at each step before the next set of experiments. Analysis metrics in each case included device ED, powder chamber retention, device retention (separate from the powder chamber), and aerosolization characteristics. Device and component selection was based on the best match to the target conditions, for example, MMAD ≤1.75 μm with the highest ED.

Initial evaluation of the inline DPI devices considered Cases 1 through 4 operated in the horizontal position with the compressed air gas source. The devices were actuated directly into the NGI preseparator inlet with the NGI operated at 45 LPM and positioned on its side (oriented vertically). A custom adaptor was used to position the device outlet ∼3 cm away from the NGI inlet and enable the entrainment of coflow air from the environment (T = 22°C ± 3°C and RH = 50% ± 5%). The NGI was held at room temperature, and individual stages were coated with MOLYKOTE® 316 silicone spray (Dow Corning, Midland, MI) to minimize particle bounce and re-entrainment. An induction port was not included at the NGI inlet as the aerosol lost in this apparatus cannot be considered in the calculation of the MMAD. Hence, the applied system without the induction port can be viewed as providing a more complete picture of the particle size distribution exiting the inline DPI than when an induction port is included. The NGI was operated at a higher flow rate (45 LPM) than the expected device flow rate (∼15 LPM) due to the relatively high velocity exiting the inline DPI. The NGI flow rate of 45 LPM was sufficiently high as to capture nearly all the aerosol while maintaining reasonable stage cutoff diameters for evaluating a small size aerosol. After horizontal assessment of the inline DPIs, the best case device was operated in a vertical (upward) position. This required suspending the NGI upside down to determine if vertical actuation of the device influences performance. In each case, ED, powder chamber, and device retention were based on the amount of initially loaded drug. FPF values were based on the percentage of device ED.

Based on inline DPI device assessments, the best performing case was selected and used to test cannula and MP performance. Experimental conditions were nearly identical to those used for device assessments. The compressed air gas source was again used to operate the inline DPI. Figure 5a and b illustrate the interface devices (cannula and MP) positioned at or within the NGI inlet. In testing the cannulas, both horizontal device positioning and vertical device positioning were considered. For the MPs, only horizontal device positioning was considered. As with the powder chamber and device, cannula or MP deposition was based on the amount of loaded drug. Evaluation of MMAD out of the cannula or MP was assessed to determine if the aerosol size had increased or decreased compared with the inline DPI outlet.

FIG. 5.

Experimental setup for testing the inline pediatric DPI operated with compressed air gas source with the patient interface connected and the aerosol directly entering the NGI with the (a) nasal cannula and (b) MP interfaces. NGI, Next Generation Impactor.

Aerosol delivery through the extrathoracic airways was tested using the best performing inline DPI paired with the best performing nasal cannula or MP. The effect of cannula prong outlet angle (Cannula 2a vs. 2b) was also assessed. For N2L delivery, the experimental setup is shown in Figure 6a and b. In practice, the inline DPI is intended to be held in one hand and the ventilation bag operated with the other. Oral delivery is depicted in Figure 6c and d. In both cases, aerosol reaching the trachea was captured on a filter. To simulate device operation as it is intended to be used in practice, airflow was supplied to the device and in vitro model using a 1 L ventilation bag. The bag was firmly compressed with one hand by an operator with a targeted delivery time of 3 seconds. As with all deposition calculations, extrathoracic loss and filter delivery efficiencies were based on loaded dose. Total drug recovery was also considered for the extrathoracic experiments to ensure that environmental losses of the aerosol were negligible.

FIG. 6.

Images of the experimental setups: (a) schematic of the setup for testing N2L administration of the aerosol through the pediatric NT model to a tracheal filter; (b) image of the setup for N2L delivery in the pediatric NT geometry; (c) schematic of the setup for testing oral administration of the aerosol through the pediatric MT model to a tracheal filter; and (d) image of the setup for oral delivery in the pediatric MT geometry.

Evaluation of airflow delivery

Different device resistances and attachments alter the targeted flow rate through the system for both compressed air and ventilation bag actuation. To quantify flow rate values, a flow meter (Sensirion EM1; Sensirion AG, Stafa, Switzerland) was used at the device inlets. Flow rate recordings (SensiView, Sensirion AG) were used to assess average flow rate, total delivered air volume, and aerosol delivery time. Comparisons were also made between averages for compressed air and ventilation bag operation of the devices.

Aerosol performance characterization methods

After aerosolization, drug masses retained in the powder chamber, inline DPI, and SL cannula or MP and the drug collected on the preseparator, impaction plates, and the filter of the NGI were recovered by washing with appropriate volumes of deionized water and quantified by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) analysis. The mass of AS retained in the powder chamber, inline DPI, and cannula or MP, determined by HPLC, was expressed as a percentage of the loaded AS dose. The inline DPI ED was calculated by subtracting the mass of AS retained in the powder chamber and device from the loaded AS dose. Likewise, the cannula ED and MP ED were calculated by subtracting the AS retained in the inline DPI and either the cannula or MP from the loaded dose. In addition, the nasal or MT model and filter deposition were determined using the same methods. Model and filter deposition were also expressed as a percentage of the loaded dose. Recovery values were expressed as a percentage of the total amount of drug on all components (inline DPI, cannula or MP, model, and filter) compared with the loaded AS dose.

To determine the nominal dose of AS in the EEG-AS formulation, known masses of the formulation were dissolved in 50 mL of water, and the mean amount of AS per milligram of formulation was determined using the HPLC analysis. For each aerosolization experiment, the measured formulation AS content and the mass of formulation loaded into the capsule were used to determine the nominal dose of AS.

The cutoff diameters of each NGI stage at the operating flow rate of 45 LPM were calculated using the formula specified in USP 35 (Chapter 601, Apparatus 5) and were used to calculate MMAD and FPFs of the delivered aerosol. FPF of the EEG formulation (FPF<5μm/ED) and submicrometer FPF (FPF<1μm/ED) were defined as the mass fractions less than 5 μm and 1 μm, respectively, expressed as a percentage of the ED. MMAD, FPF<5μm/ED, and FPF<1μm/ED were calculated by linear interpolation using a plot of cumulative percentage drug mass versus cutoff diameter.

Results

Performance of inline DPIs

Aerosolization performance of inline DPI Cases 1 through 4 is presented in Table 1. Devices were actuated with the compressed air gas source, and all cases were oriented horizontally except for Case 4, which was actuated horizontally and vertically. Considering Cases 1 through 4 operated horizontally, straight-through designs without bypass flow (Cases 3 and 4) had statistically higher ED values. Both Cases 3 and 4 performed well with ED values of ∼85% and MMAD values of 1.7 μm. Of these devices, Case 4 demonstrated lower variability in ED and FPF values. Furthermore, Case 4 satisfied all initial device design metrics including FPF<5μm/ED ≥ 90%, FPF<1μm/ED ≥ 20%, and MMAD ≤1.75 μm. As a result, Case 4 was selected for further testing and evaluation in a vertical orientation, consistent with N2L delivery. In the vertical configuration, Case 4 performance was very similar; however, FPF<1μm/ED fell just outside the target range to a value of 19%. Considering that all other design metrics were met, this minor reduction in FPF was viewed as acceptable.

Table 1.

Aerosolization Performance of Inline Dry Powder Inhaler Cases 1 Through 4

| Description | Case 1 1.52/1.52a |

Case 2 1.4/1.8 |

Case 3 2.39/2.39 |

Case 4 1.83/2.39 |

Case 4 Verticalb |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ED (%)* | 66.3 (3.1) | 70.2 (1.7) | 85.1 (8.8)** | 86.0 (1.4)** | 86.5 (3.0)** |

| Chamber (%)* | 24.5 (3.6) | 20.6 (2.9) | 8.7 (3.0)** | 10.4 (1.0)** | 9.3 (3.2)** |

| Device (%) | 9.2 (0.6) | 9.2 (2.9) | 6.2 (5.8) | 3.6 (0.5) | 4.2 (0.8) |

| FPF<5μm/ED (%) | 86.3 (8.2) | 88.7 (3.9) | 86.1 (10.5) | 90.9 (1.4) | 90.7 (4.5) |

| FPF<1μm/ED (%) | 23.6 (4.3) | 22.0 (1.7) | 20.7 (3.3) | 19.5 (0.5) | 18.9 (2.9) |

| MMAD (μm) | 1.60 (0.16) | 1.63 (0.06) | 1.70 (0.18) | 1.69 (0.01) | 1.74 (0.10) |

Mean aerosol characteristics with SD shown in parenthesis, n = 3.

Devices were operated with compressed air.

Inlet/outlet capillary diameters (mm).

All other cases oriented the powder chamber horizontally with respect to gravity.

p < 0.05 significant effect of case on % ED and % chamber drug retention (one-way ANOVA).

p < 0.05 significant difference compared with Case 1 (post-hoc Tukey).

ED, emitted dose; FPF, fine particle fraction; MMAD, mass median aerodynamic diameter; SD, standard deviations.

Theoretically predicted and measured flow rate data through the inline DPIs are presented in Table 2. The theoretical values are based on analytical pressure and resistance relationships applied to the powder chamber and bypass flow paths with a constant upstream pressure of 6 kPa. The measured values include the Q90 metric, which is the flow rate that 90% of the measured data points fall below. Furthermore, the measured values only report total flow through the full device based on the position of the flow meter (Fig. 6a, c). Good agreement is observed between the theoretical and measured values, especially for the designs without bypass flow (Cases 3 and 4). Differences in the Case 3 and Case 4 flow rates compared with the targeted value of 15 LPM arise from different resistances associated with alterations in the inlet and outlet capillary diameters. Case 4 actuation conditions produced an average flow rate of 12.6 LPM, a delivered air volume of 731 mL, and a delivery time of 3.46 seconds. These values were viewed as sufficiently close to the targeted ventilation conditions.

Table 2.

Theoretical and Measured Flow Rate Data for Inline Dry Powder Inhaler Cases 1 Through 4

| Description | Case 1 | Case 2 | Case 3 | Case 4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Theoretical values | ||||

| Powder chamber (LPM) | 6.4 | 7.1 | N/A | N/A |

| Full device (LPM) | 14.5 | 14.6 | 18.8 | 13.7 |

| Measured values | ||||

| Q90 (LPM) | 12.8 (0.5) | 13.5 (0.9) | 19.5 (0.0) | 13.1 (0.1) |

| Average (LPM) | 12.3 (0.5) | 12.9 (1.0) | 18.6 (0.2) | 12.6 (0.1) |

| Total volume (mL) | 750 (25) | 700 (47) | 732 (9) | 731 (5) |

| Delivery time (s) | 3.64 (0.02) | 3.25 (0.02) | 2.34 (0.00) | 3.46 (0.00) |

Mean values with SD shown in parenthesis, n = 3.

Devices were operated with compressed air.

LPM, liters per minute (L/min).

N2L aerosol delivery

To maximize N2L aerosol delivery, performance of Case 4 was first assessed in connection with Cannulas 1 and 2 (with 2a outlet prongs) actuated directly into the NGI (Fig. 5a and Table 3). The inline DPI was actuated with the compressed air gas source with the powder chamber in the horizontal position. While the ED was not statistically different between the cannulas, Cannula 2a had depositional drug loss below 5%, which was significantly lower than Cannula 1 and was selected for additional testing. Due to a combination of cannula deposition and small increases in chamber and device losses, the overall cannula ED was observed to be 76.5% of the loaded dose. The presence of the cannula also increased the MMAD to 1.84 μm. It is not known if this increase in size is due to turbulent deposition of smaller particles in the aerosol size distribution.

Table 3.

Aerosolization Performance of the Case 4 Inline Dry Powder Inhaler with Different Outlet Nasal Cannulas

| Description | Cannula 1 | Cannula 2a |

|---|---|---|

| Cannula ED (%) | 75.1 (2.7) | 76.5 (0.7) |

| Chamber (%) | 11.9 (2.9) | 10.0 (1.2) |

| Device (%) | 6.9 (0.4) | 9.2 (0.5)* |

| Cannula (%) | 6.1 (0.7) | 4.3 (0.4)* |

| FPF<5μm/ED (%) | 88.6 (3.2) | 87.0 (3.8) |

| FPF<1μm/ED (%) | 17.3 (0.7) | 17.1 (0.1) |

| MMAD (μm) | 1.83 (0.01) | 1.84 (0.04) |

Mean aerosol characteristics with SD shown in parenthesis, n = 3.

Device was operated with compressed air.

p < 0.05 significant difference (t-test).

Aerosol delivery through the pediatric NT model, as shown in Figure 6a and b, with the Case 4 device and Cannulas 2a and 2b designs operated with the ventilation bag is presented in Table 4. Differences between Cannulas 2a and 2b (inward sloped prongs) were not significant; however, Cannula 2b appeared to reduced variability in filter delivery, likely because of improved positioning in the nostrils. Cannula 2b also satisfied the design criteria of <10% NT loss and ≥60% of loaded dose reaching the tracheal filter. Vertical operation with Cannula 2b had a minor effect on performance with tracheal filter delivery decreased to 56.7%.

Table 4.

Aerosolization and Lung Delivery Efficiency for Nose-to-Lung Administration (Case 4 Device, Cannula 2) Through the 5-Year-Old Pediatric Nose–Throat Geometry

| Description | Cannula 2a | Cannula 2b | Cannula 2b vertical |

|---|---|---|---|

| Chamber (%) | 15.5 (5.4) | 11.6 (1.4) | 12.4 (3.7) |

| Device (%) | 10.7 (1.0) | 10.3 (0.9) | 11.3 (2.3) |

| Cannula (%) | 5.1 (1.2) | 6.1 (1.0) | 7.2 (2.2) |

| Cannula ED (%) | 68.7 (5.5) | 71.9 (0.5) | 69.0 (3.6) |

| NT loss (%) | 7.6 (2.3) | 8.3 (1.2) | 7.4 (2.8) |

| Tracheal filter (%) | 58.8 (6.0) | 60.7 (1.2) | 56.7 (0.4) |

| Recovery (%) | 97.7 (2.7) | 97.1 (0.9) | 95.1 (1.5) |

Mean aerosol characteristics with SD shown in parenthesis, n = 3.

Device was operated with ambient air and ventilation bag.

NT, nose–throat.

Airflow conditions for compressed air and ventilation bag actuation are compared in Figure 7 and Table 5. Compressed air flow through the device produces a square waveform flow profile, as expected. For ventilation bag actuation, the flow profile quickly reaches a peak flow and then decelerates. Average flow metrics for these two approaches are compared in Table 5. It is observed that the ventilation bag has an average flow rate of approximately 2 LPM lower and delivers an air volume approximately 130 mL smaller than with compressed air. Nevertheless, device emptying and cannula deposition fractions are very similar for both modes of operation. This indicates that adequate air volume is available in both cases to empty the powder.

FIG. 7.

Measured flow rate waveforms for compressed air and ventilation bag gas sources.

Table 5.

Comparison of Flow Rate Data for the Inline Dry Powder Inhaler (Case 4) Operated with the Compressed Air Gas Source or Ventilation Bag

| Description | Compressed aira | Ventilation bag |

|---|---|---|

| Q90 (LPM) | 13.1 (0.1) | 13.7 (0.4) |

| Average (LPM) | 12.6 (0.1) | 10.6 (0.3) |

| Total volume (mL) | 731 (5) | 599 (19) |

| Delivery time (s) | 3.46 (0.00) | 3.37 (0.22) |

SD shown in parenthesis, n = 3.

Data from Table 2 is repeated for comparison.

Furthermore, standard deviation values of flow rate data (Table 5) produce coefficients of variation (∼3%) that are relatively small implying that operation with the ventilation bag is reasonably reproducible based on a single operator.

Oral aerosol delivery

Aerosolization performance for the Case 4 inline DPI connected to MP 1 and MP 2 is presented in Table 6. As shown in Figure 5b, the MP was positioned adjacent to the NGI inlet, and the DPI was actuated in the horizontal position with compressed air. Performance was not statistically different between the MP 1 and MP 2 designs. MP 2 was selected based on a lower trend in MP and powder chamber retention and slightly higher ED (78.1%). Compared with cannula performance, depositional loss was similar (∼5%), and measured MMAD exit size only varied by approximately 0.1 μm. This small increase in exit size may be due to turbulence-driven deposition.

Table 6.

Aerosolization Performance of the Case 4 Inline Dry Powder Inhaler with Different Mouthpieces

| Description | MP 1 | MP 2 |

|---|---|---|

| MP ED (%) | 76.3 (5.1) | 78.1 (4.0) |

| Chamber (%) | 9.6 (2.2) | 7.2 (2.4) |

| Device (%) | 6.7 (1.8) | 8.8 (1.2) |

| MP (%) | 7.4 (1.2) | 6.0 (1.5) |

| FPF<5μm/ED (%) | 88.9 (1.8) | 88.2 (0.4) |

| FPF<1μm/ED (%) | 21.7 (0.6) | 23.2 (0.4) |

| MMAD (μm) | 1.98 (0.04) | 1.92 (0.11) |

Mean aerosol characteristics with SD shown in parenthesis, n = 3.

Device was operated with compressed air.

Performance of the inline DPI (Case 4) with MP 2 connected to the pediatric MT geometry is presented in Table 7. When connected to the oral airway geometry, shown in Figure 6c and d, the MP deposition fraction was reduced below 5% and MT depositional loss was 6.6%, which was just below best case nasal deposition with cannula delivery (7.6%), and below the target value of 10%. Powder deposition was observed on the back of the pediatric throat indicating that an air jet exits the inline DPI outlet cannula, progresses through the MP and oral airway geometry, and strikes the back of the throat. Further reductions in MT deposition will likely require improved dissipation of this air jet effect. Tracheal filter delivery was 63.8% of the loaded powder, which was similar to N2L delivery and greater than the 60% target value.

Table 7.

Aerosolization and Lung Delivery Efficiency for Oral Administration (Case 4 Device, MP 2) Through the 5-Year-Old Pediatric Mouth–Throat Geometry

| Description | MP 2 |

|---|---|

| Chamber (%) | 11.2 (2.1) |

| Device (%) | 10.6 (1.5) |

| MP (%) | 4.6 (0.5) |

| MP ED (%) | 73.6 (0.5) |

| MT loss (%) | 6.6 (1.1) |

| Tracheal filter (%) | 63.8 (2.2) |

| Recovery (%) | 96.8 (3.1) |

Mean aerosol characteristics with SD shown in parenthesis, n = 3.

Device was operated with ambient air and ventilation bag.

MT, mouth–throat.

Discussion

This study has developed an inline DPI with the potential to efficiently deliver pharmaceutical aerosols to the lungs of children while overcoming some of the current usage challenges associated with other powder delivery platforms. Considering aerosolization performance, the new inline device met all the initial targets, with Case 4 (operated horizontally) achieving 86.0% ED and a 1.7 μm mean MMAD. The FPFs <5 μm and <1 μm (based on ED) were 90.9% and 19.5%, respectively. Moreover, this performance was maintained when the inhaler was operated vertically. For comparison, the FPF of most commercial DPIs based on a size of <5 μm is in the range of 10%–45%.(57) With the inline device, the aerosol MMAD exiting the cannula and MP did increase slightly above the target of 1.75 μm. Targeted lung delivery efficiencies were also achieved with best-case tracheal filter doses of 63.8% and 60.7% for oral and N2L administration, respectively. In comparison, commercial inhalers when tested with pediatric inhalation profiles and a MT geometry consistent with a 5-year-old produced tracheal delivery fractions of 5%–22%.(13) Increasing pediatric subject inhalation conditions to a range of 6–14 years with a 1.5 L inhaled volume increased lung delivery efficiency to ∼30% with the Turbuhaler DPI.(58)

Operation of the inline DPI with positive pressure airflow may have multiple advantages, especially when employed with preschool age children. A significant concern with DPI use in children is generating sufficient airflow and inhaling consistently through the device over a period of months after initial training.(14,21,27,28,59,60) For trained children in a laboratory setting, Lexmond et al.(27) reported high intersubject variability among inhaled waveforms within each age group considered (e.g., 5–6 years) and across a range of ages between 5 and 12 years. The inline DPI operated with a positive pressure ventilation bag addresses the concerns of sufficient and consistent inhalation directly by providing both the aerosol and a full inhalation breath to the child. This approach also eliminates the issue of intersubject inhalation consistency, as the inhalation volume and flow rate can be defined. It is anticipated that correct inhalation usage can be best achieved by removing this responsibility from the child and giving it to the caregiver who is administering the treatment.

The use of positive pressure aerosol delivery can also be used to overcome a number of challenges identified by Lexmond et al.(27) It is expected that the MT obstructions observed in their in vivo study(27) were the result of negative pressure generated in the airway occurring during inhalation against a resistance. In contrast, the inline DPI provides positive pressure to the MT or nasal region, thereby not collapsing but possibly expanding these airways. In particular, expansion of the nares and pharynx may further improve aerosol delivery efficiency during N2L or oral administration, respectively. The positive pressure source prevents exhalation through the device. Exhalation into passive DPIs can prevent deaggregation of a single dose in capsule-based platforms or can degrade aerosolization of an entire drug reservoir in multidose devices. The device can also help to maintain a breath-hold by instructing the child to maintain a seal on the interface over a specified time period (e.g., 10 seconds).

Delivery of the aerosol with positive pressure airflow may also improve and potentially be used to target deposition in the lungs. As with the extrathoracic airways, positive pressure delivery will tend to increase airway size compared with negative pressure inhalation against a resistance. Increasing airway size may be beneficial for improving deep lung aerosol deposition and may help to improve delivery through constricted or partially occluded segments. The average conducting airway volume for a 5-year-old is approximately 46 mL. Administration of the aerosol with 750 mL of air should foster good delivery of the aerosol to all regions of the lungs. Reduced actuation volumes will need to be selected for younger children or could be used to limit deposition of the aerosol in the alveolar region. It is expected that the inline DPI will perform similarly with reduced actuation air volume considering that good performance was previously observed with a similar device and formulation operated with 10 mL air volumes delivered over five pulses.(1,12,31)

Use of a positive pressure gas source with the inline DPI enables N2L administration of the aerosol. For children who cannot form a seal on a MP, who are likely in the range of <5 years of age, N2L administration offers an option for the rapid delivery of DPI aerosols. For older children who can use a MP, N2L delivery provides an option for delivering the aerosol that may simultaneously treat the nose and lungs. As described in the Introduction section, clinical indications that may benefit from treatment of the nasal–lung airways in combination may include CF when nasal bacteria is suspected and asthma when nasal inflammation is present. The current deposition of approximately 7%–8% of the loaded dose in the nasal airways can be tuned to a desired drug mass by adjusting the aerosol particle size or flow rate. For surface active medications, such as inhaled corticosteroids, a targeted nasal dose may be sought to achieve uniform surface concentration of the drug throughout the nose and tracheobronchial airways.

This study indicates that using the best case inline DPI platform, high-efficiency N2L administration of a powder-based aerosol may be possible. Previous studies on N2L powder delivery have typically considered infant conditions and reported very low lung delivery efficiencies when an airway model is included.(5) Studies comparing oral vs. nasal aerosol administration in the same subject report that the nasal route reduces lung delivery efficiency by a factor of twofold.(61,62) In this study, MT depositional loss was very similar to nasal deposition. As both extrathoracic deposition values were low (<10%), lung delivery efficiency was not largely affected. Moreover, in vitro predictions of nasal depositional loss are consistent with other studies employing multiple pediatric nasal geometries.(47,63) For example, the d2Q impaction parameter for the 1.7 μm aerosol delivered at 15 LPM is approximately 40 μm2 LPM, which based on the study of Golshahi et al.(47) across 14 pediatric nasal models corresponds to nasal deposition in the range of approximately 0%–12%. The predicted value range of approximately 8% nasal deposition in this study is near the middle of the range presented by Golshahi et al.(47) In contrast, employing a typical DPI aerosol size of 6 μm at a flow rate of 15 LPM results in a predicted nasal deposition range of 25%–75% based on the data of Golshahi et al.(47) Reducing nasal depositional loss below 5% across multiple subjects will require a 1.3 μm aerosol or reducing the flow rate by approximately half.(47)

While a positive pressure approach provides a number of advantages in delivering powder-based aerosols to children, there are also some disadvantages including increased requirements of the caregiver and increased size of the device. A principle behind the positive pressure approach is removing the requirement for correct and reproducible inhalation from the child and placing this responsibility on the caregiver. Additional increased caregiver responsibilities include ensuring a seal with the MP or nasal cannula interface. It is expected that these interfaces will be easier to seal than a facemask and will provide more direct access (with less depositional loss) to the lungs. In using the oral interface, the caregiver should ensure that the child is inhaling to accept the incoming air and may need to pinch the nose to prevent aerosol from entering the nasal cavity. With the nasal interface, closure of the mouth should be verified. The ventilation bag should be operated with a firm typically one-handed squeeze such that it empties in ∼3 seconds with the current system. Only one actuation was required for the 10 mg powder mass considered in this study. While this approach does increase responsibilities of the caregiver, it is expected that these simple tasks can be better executed compared with requiring a child to use a conventional DPI. The benefit is likely improved and reproducible administration of the aerosol.

Another potential disadvantage of the inline DPI operated with positive pressure is the requirement for a ventilation bag and the associated increase in total device size. This concern may be reduced through the use of a collapsible ventilation bag (Fig. 8), which folds into a pocket-sized carrying case. The compressed volume is approximately equal to that of a metered dose inhaler (MDI) spacer. We view this increase in device size as an acceptable price for the potential to increase lung delivery efficiency to the lungs from 5% to 10% with conventional devices to 60%–70% (or higher with future optimization) as well as the improved usability and potential error elimination associated with positive pressure operation.

FIG. 8.

Images of the pediatric inline DPI system including (a) collapsible ventilation bag, (b) pediatric inline DPI with a size 0 capsule, and (c) nasal and oral interfaces.

One application that may benefit from the positive pressure DPI is the administration of inhaled antibiotics to children with CF. Liquid formulations of antibiotics such as tobramycin inhalation solution (TIS) often require long delivery times, up to 20 minutes per dose,(64,65) not counting the additional time for necessary cleaning and disinfecting of the nebulizer. Dry powder delivery of inhaled antibiotics has the advantage of dramatically reducing treatment time.(65–67) For example, the TOBI Podhaler® with spray-dried PulmoSphere® tobramycin inhalation powder (TIP) is currently approved for use by CF patients older than 6 years.(65,67) The TIP treatment requires the inhalation of four capsules loaded individually into the device and inhaled separately, for a total loaded powder dose of 200 mg and requires approximately 6 minutes.(67) The inhaled volume for Podhaler operation is >1 L with one or two breaths required to empty each capsule.(67) Based on in vivo gamma scintigraphy data in a healthy adult patient population, the mean lung delivery efficiency was 34.2% of the loaded dose with MT deposition of 43.6%. There are currently no recommended devices for administering inhaled aerosols to children with CF 5 years old and younger, despite clear clinical efficacy of TIS in this age range.(68,69) The inline DPI may be used to fill this need. As a vibrating capsule is not required, the inline DPI can be filled with larger powder masses, provided that the inlet jet does not impinge on the powder bed.(30) Ideally, the inline DPI can be filled with a single dose that is efficiently delivered over one or more actuations, thereby significantly reducing the number of required delivery operations and administration time. This goal will require additional formulation work and device engineering, which are currently in progress.

Primary limitations of this study are the consideration of a limited number of devices and conditions as well as assessment in single airway geometries. An advantage of the inline DPI is flexibility in the hollow capillary configuration in terms of size and orientation. The consideration of four total devices is a relatively small set. However, these devices achieved the desired aerosolization for the test dose considered and demonstrated that performance was improved without the use of bypass air. Furthermore, the outlet jet did not result in excessive depositional loss in the cannula or MP. Further study is required to understand why the aerosol size increased in the cannula. Cases employing actuation with the ventilation bag were all conducted by the same person. Operation at different actuation pressures, within a reasonable range, should be explored considering that not all users will actuate the device the same. In this study, the powder fill mass of 10 mg was intended to be for general platform development. Additional device modifications will be required for optimal performance with smaller or larger powder masses. For significantly larger powder masses, an asymmetrical capsule chamber design may be adapted to prevent the inlet jet from impinging on the powder bed.

Considering analysis of performance, the use of a single oral and single nasal airway representative of a 5-year-old child is a limitation. These in vitro models are assumed to be reasonable representations based on comparisons with the mean anatomical data. However, both models are rigid and do not include the potential dynamic occlusion observed by Lexmond et al.(27) These models have not yet been compared with deposition in other models or in vivo depositional data across a range of subjects. In addition, significant intersubject variability is expected in the oral and nasal airways of children at all ages. Therefore, results from these models should be interpreted with caution. One reassuring comparison described earlier found that the nasal deposition predicted with the pediatric in vitro model was nearly in the middle of the range of potential values across 14 subjects(47) at the same impaction parameter.

In conclusion, this study has proposed and initially developed an inline DPI for delivering spray-dried formulations to children using positive pressure operation. High lung delivery efficiencies were observed based on tracheal filter doses with in vitro models of 60% or more for administration with nasal and oral interfaces. The device required 6 kPa pressure for operation, which resulted in good aerosolization of a 10 mg spray-dried formulation, and was easy to generate with a ventilation bag. Best performance of the device was observed without bypass flow, and the device could be operated horizontally or vertically. Operation of the device with positive pressure enabled effective N2L and repeatable aerosol administration with a DPI for the first time, which may be beneficial for subjects who are too young to use a MP or to simultaneously treat the nasal and lung airways. Additional expected advantages of positive pressure operation include delivery of a consistent inhalation each time the device is used, reduced potential to obstruct the upper airways, and prevention of exhalation through the DPI. These advantages are expected to make the device easier to use by children. Future studies are needed to optimize the device for use with other formulations, at different dose loadings and for different ages. The platform may be well suited to rapidly administer high-dose antibiotics to children with compromised lung function, as in the case of CF.

Acknowledgments

Research reported in this publication was supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HD087339 and by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the National Institutes of Health under Award Number R01HL139673. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Author Disclosure Statement

Virginia Commonwealth University is currently pursuing patent protection of devices and methods described in this study which, if licensed and commercialized, may provide a future financial interest to the authors.

Reviewed by:

Philip Kuehl

Anne Lexmond

References

- 1. Farkas D, Hindle M, and Longest PW: Development of an inline dry powder inhaler that requires low air volume. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2018;31:255–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Behara SRB, Longest PW, Farkas DR, and Hindle M: Development of high efficiency ventilation bag actuated dry powder inhalers. Int J Pharm. 2014;465:52–62 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Pornputtapitak W, El-Gendy N, Mermis J, O'Brein-Ladner A, and Berkland C: NanoCluster budesondie formulations enable efficient drug delivery driven by mechanical ventilation. Int J Pharm. 2014;462:19–28 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Feng B, Tang P, Leung SSY, Dhanani J, and Chan H-K: A novel in-line delivery system to administer dry powder mannitol to mechanically ventilated patients. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2017;30:100–107 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Laube BL, Sharpless G, Shermer C, Sullivan V, and Powell K: Deposition of dry powder generated by solovent in Sophia Anatomical infant nose-throat (SAINT) model. Aerosol Sci Technol. 2012;46:514–520 [Google Scholar]

- 6. Pohlmann G, Iwatschenko P, Koch W, Windt H, Rast M, Gama de Abreu M, Taut FJH, and De Muynck C: A novel continuous powder aerosolizer (CPA) for inhalative administration of highly concentrated recombinant surfactant protein-C (rSP-C) surfactant to perterm neonates. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2013;26:370–379 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Manion JR, Cape SP, McAdams DH, Rebits LG, Evans S, and Sievers RE: Inhalable antibiotics manufactured through use of near-critical or supercritical fluids. Aerosol Sci Technol. 2012;46:403–410 [Google Scholar]

- 8. Walenga RL, Longest PW, Kaviratna A, and Hindle M: Aerosol drug delivery during noninvasive positive pressure ventilation: Effects of intersubject variability and excipient enhanced growth. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2017;30:190–205 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Okuda T, Tang P, Yu J, Finlay WH, and Chan H-K: Powder aerosol delivery through nasal high-flow system: In vitro feasibility and influence of process conditions. Int J Pharm. 2017;533:187–197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Longest PW, Golshahi L, Behara SRB, Tian G, Farkas DR, and Hindle M: Efficient nose-to-lung (N2L) aerosol delivery with a dry powder inhaler. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2015;28:189–201 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Tang P, Chan HK, Rajbhandari D, and Phipps P: Method to introduce mannitol powder to intubated patients to improve sputum clearance. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2011;24:1–9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Farkas D, Hindle M, and Longest PW: Application of an inline dry powder inhaler to deliver high dose pharmaceutical aerosols during low flow nasal cannula therapy. Int J Pharm. 2018;546:1–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Below A, Bickmann D, and Breitkreutz J: Assessing the performance of two dry powder inhalers in preschool children using an idealized pediatric upper airway model. Int J Pharm. 2013;444:169–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Fink JB: Delivery of inhaled drugs for infants and small children: A commentary on present and future needs. Clin Ther. 2012;34:S36–S45 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Smaldone GC, Berg E, and Nikander K: Variation in pediatric aerosol delivery: Importance of facemask. J Aerosol Med. 2005;18:354–363 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. El Taoum KK, Xi J, Kim J, and Berlinski A: In vitro evaluation of aerosols delivered via the nasal route. Respir Care. 2015;60:1015–1025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Lin H-L, Harwood RJ, Fink JB, Goodfellow LT, and Ari A: In vitro comparison of aerosol delivery using different face masks and flow rates with a high-flow humidity system. Respir Care. 2015;60:1215–1219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Smaldone GC, Sangwan S, and Shah A: Facemask design, facial deposition, and delivered dose of nebulized aerosols. J Aerosol Med. 2007;20:S66–S77 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Ari A, Harwood R, Sheard M, Dailey P, and Fink JB: In vitro comparison of heliox and oxygen in aerosol delivery using pediatric high flow nasal cannula. Pediatr Pulmonol. 2011;46:795–801 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Everard ML: Inhaler devices in infants and children: Challenges and solutions. J Aerosol Med. 2004;17:186–195 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Devadason SG: Recent advances in aerosol therapy for children with asthma. J Aerosol Med. 2006;19:61–66 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lindert S, Below A, and Breitkreutz J: Performance of dry powder inhalers with single dosed capsules in preschool children and adults using improved upper airway models. Pharmaceutics. 2014;6:36–51 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Goralski JL, and Davis SD: Breathing easier: Addressing the challenges of aerosolizing medications to infants and preschoolers. Respir Med. 2014;108:1069–1074 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Smith IJ, Bell J, Bowman N, Everard M, Stein S, and Weers JG: Inhaler devices: What remains to be done? J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2010;23:S25–S37 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Fink JB: Inhalers in asthma management: Is demonstration the key to compliance? Respir Care. 2005;50:598–600 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Fink JB, and Rubin BK: Problems with inhaler use: A call for improved clinician and patient education. Respir Care. 2005;50:1360–1375 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Lexmond AJ, Kruizinga TJ, Hagedoorn P, Rottier BL, Frijlink HW, and De Boer AH: Effect of inhaler design variables on paediatric use of dry powder inhalers. PLoS One. 2014;9:e99304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Lexmond AJ, Hagedoorn P, Frijlink HW, Rottier BL, and de Boer AH: Prerequisites for a dry powder inhaler for children with cystic fibrosis. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0183130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Weers J, Ung K, Le J, Rao N, Ament B, Axford G, Maltz D, and Chan L: Dose emission characteristics of placebo PulmoSphere (R) particles are unaffected by a subject's inhalation maneuver. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2013;26:56–68 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Longest PW, and Farkas D: Development of a new inhaler for high-efficiency dispersion of spray-dried powders using computational fluid dynamics (CFD) modeling. AAPS J. 2018;21:25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Farkas D, Hindle M, and Longest PW: Efficient nose-to-lung aerosol delivery with an inline DPI requiring low actuation air volume. Pharm Res. 2018;35:194. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Adams RJ, Fuhlbrigge AL, Finkelstein JA, and Weiss ST: Intranasal steroids and the risk of emergency department visits for asthma. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2002;109:636–642 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Dixon AE: Rhinosinusitis and asthma: The missing link. Curr Opin Pulm Med. 2009;15:19–24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Aanæs K: Bacterial sinusitis can be a focus for initial lung colonisation and chronic lung infection in patients with cystic fibrosis. J Cystic Fibrosis. 2013;12:S1–S20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Bonestroo HJ, de Winter-de Groot KM, van der Ent CK, and Arets HG: Upper and lower airway cultures in children with cystic fibrosis: Do not neglect the upper airways. J Cystic Fibrosis. 2010;9:130–134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Robertson JM, Friedman EM, and Rubin BK: Nasal and sinus disease in cystic fibrosis. Paediatr Respir Rev. 2008;9:213–219 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Everard ML, Devadason SG, and LeSouef PN: In vitro assessment of drug delivery through an endotracheal tube using a dry powder inhaler delivery system. Thorax. 1996;51:75–77 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Son Y-J, Longest PW, and Hindle M: Aerosolization characteristics of dry powder inhaler formulations for the excipient enhanced growth (EEG) application: Effect of spray drying process conditions on aerosol performance. Int J Pharm. 2013;443:137–145 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Son Y-J, Longest PW, Tian G, and Hindle M: Evaluation and modification of commercial dry powder inhalers for the aerosolization of submicrometer excipient enhanced growth (EEG) formulation. Eur J Pharm Sci. 2013;49:390–399 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Longest PW, Son Y-J, Holbrook LT, and Hindle M: Aerodynamic factors responsible for the deaggregation of carrier-free drug powders to form micrometer and submicrometer aerosols. Pharm Res. 2013;30:1608–1627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Hindle M, and Longest PW: Condensational growth of combination drug-excipient submicrometer particles for targeted high efficiency pulmonary delivery: Evaluation of formulation and delivery device. J Pharm Pharmacol. 2012;64:1254–1263 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. Longest PW, and Hindle M: Numerical model to characterize the size increase of combination drug and hygroscopic excipient nanoparticle aerosols. Aerosol Sci Technol. 2011;45:884–899 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Longest PW, and Hindle M: Condensational growth of combination drug-excipient submicrometer particles: Comparison of CFD predictions with experimental results. Pharm Res. 2012;29:707–721 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Longest PW, Tian G, Li X, Son Y-J, and Hindle M: Performance of combination drug and hygroscopic excipient submicrometer particles from a softmist inhaler in a characteristic model of the airways. Ann Biomed Eng. 2012;40:2596–2610 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Tian G, Longest PW, Li X, and Hindle M: Targeting aerosol deposition to and within the lung airways using excipient enhanced growth. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2013;26:248–265 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Tian G, Hindle M, and Longest PW: Targeted lung delivery of nasally administered aerosols. Aerosol Sci Technol. 2014;48:434–449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Golshahi L, Noga ML, Thompson RB, and Finlay WH: In vitro deposition measurement of inhaled micrometer-sized particle in extrathoracic airways of children and adolescents during nose breathing. J Aerosol Sci. 2011;42:474–488 [Google Scholar]

- 48. Golshahi L, and Finlay WH: An idealized child throat that mimics average pediatric oropharyngeal deposition. Aerosol Sci Technol. 2012;46:i–iv [Google Scholar]

- 49. Delvadia R, Longest PW, and Byron PR: In vitro tests for aerosol deposition. I. Scaling a physical model of the upper airways to predict drug deposition variation in normal humans. J Aerosol Med. 2012;25:32–40 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Wei X, Hindle M, Kaviratna A, Huynh BK, Delvadia RR, Sandell D, and Byron PR: In vitro tests for aerosol deposition. VI: realistic testing with different mouth–throat models and in vitro—in vivo correlations for a dry powder inhaler, metered dose inhaler, and soft mist inhaler. J Aerosol Med Pulm Drug Deliv. 2018;31:358–371 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Phalen RF, Oldham MJ, Beaucage CB, Crocker TT, and Mortensen JD: Postnatal enlargement of human tracheobronchial airways and implications for particle deposition. Anat Rec. 1985;212:368–380 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Wachtel H, Bickmann D, Breitkreutz J, and Langguth P: Can pediatric throat models and air flow profiles improve our dose finding strategy. Respir Drug Deliv. 2010;2010:195–204 [Google Scholar]

- 53. Cheng YS: Aerosol deposition in the extrathoracic region. Aerosol Sci Technol. 2003;37:659–671 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Cheng YS, Zhou Y, and Chen BT: Particle deposition in a cast of human oral airways. Aerosol Sci Technol. 1999;31:286–300 [Google Scholar]

- 55. Xi J, and Longest PW: Transport and deposition of micro-aerosols in realistic and simplified models of the oral airway. Ann Biomed Eng. 2007;35:560–581 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. ICRP: Human Respiratory Tract Model for Radiological Protection. Elsevier Science Ltd., New York, 1994 [Google Scholar]

- 57. De Boer A, Hagedoorn P, Hoppentocht M, Buttini F, Grasmeijer F, and Frijlink H: Dry powder inhalation: Past, present and future. Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2017;14:499–512 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Ruzycki CA, Golshahi L, Vehring R, and Finlay WH: Comparison of in vitro deposition of pharmaceutical aerosols in an idealized child throat with in vivo deposition in the upper respiratory tract of children. Pharm Res. 2014;31:1525–1535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Tiddens HA, Geller DE, Challoner P, Speirs RJ, Kesser KC, Overbeek SE, Humble D, Shrewsbury SB, and Standaert TA: Effect of dry powder inhaler resistance on the inspiratory flow rates and volumes of cystic fibrosis patients of six years and older. J Aerosol Med. 2006;19:456–465 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Rubin BK, and Fink JB: Aerosol therapy for children. Respir Care Clin N Am. 2001;7:175–213 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Everard M, Hardy J, and Milner A: Comparison of nebulised aerosol deposition in the lungs of healthy adults following oral and nasal inhalation. Thorax. 1993;48:1045–1046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]