Abstract

Aromatic hydrocarbons make up a large fraction of anthropogenic volatile organic compounds and contribute significantly to the production of tropospheric ozone and secondary organic aerosol (SOA). Four toluene and four 1,2,4-trimethylbenzene (1,2,4-TMB) photooxidation experiments were performed in an environmental chamber under relevant polluted conditions (NOx ~ 10ppb). An extensive suite of instrumentation including two proton-transfer-reaction mass spectrometers (PTR-MS) and two chemical ionisation mass spectrometers ( CIMS and I− CIMS) allowed for quantification of reactive carbon in multiple generations of hydroxyl radical (OH)-initiated oxidation. Oxidation of both species produces ring-retaining products such as cresols, benzaldehydes, and bicyclic intermediate compounds, as well as ring-scission products such as epoxides and dicarbonyls. We show that the oxidation of bicyclic intermediate products leads to the formation of compounds with high oxygen content (an O : C ratio of up to 1.1). These compounds, previously identified as highly oxygenated molecules (HOMs), are produced by more than one pathway with differing numbers of reaction steps with OH, including both auto-oxidation and phenolic pathways. We report the elemental composition of these compounds formed under relevant urban high-NO conditions. We show that ring-retaining products for these two precursors are more diverse and abundant than predicted by current mechanisms. We present the speciated elemental composition of SOA for both precursors and confirm that highly oxygenated products make up a significant fraction of SOA. Ring-scission products are also detected in both the gas and particle phases, and their yields and speciation generally agree with the kinetic model prediction.

1. Introduction

Aromatic compounds represent a significant fraction of volatile organic compounds (VOCs) in the urban atmosphere and play a substantial role in the formation of tropospheric ozone and secondary organic aerosol (SOA) (Calvert et al., 2002). Typical anthropogenic sources include vehicle exhaust, solvent use, and evaporation of gasoline and diesel-fuels. Toluene, the most abundant alkylbenzene in the atmosphere, is primarily emitted by the aforementioned anthropogenic processes (Wu et al., 2014). Toluene-derived SOA is estimated to contribute approximately 17 %–29% of the total SOA produced in urban areas (Hu et al., 2008). More highly substituted aromatic compounds make up another important group of aromatic compounds as they tend to have high SOA yields (Li et al., 2016) and account for a significant fraction of non-methane hydrocarbons in the industrialised regions of China (Tang et al., 2007; Zheng et al., 2009). 1,2,4-Trimethylbenzene (1,2,4-TMB) is chosen as a model molecule to study the oxidation of more substituted aromatic compounds (i.e. trimethylbenzenes).

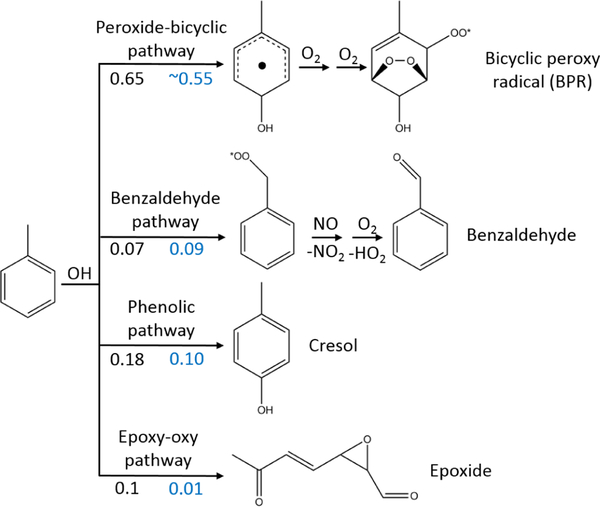

In the atmosphere, oxidation of aromatic hydrocarbons is primarily initiated by their reactions with hydroxyl radicals (OH) via H abstraction from the alkyl groups or OH addition to the aromatic ring (Fig. 1) (Calvert et al., 2002). The abstraction channels are relatively minor, leading to the formation of benzyl radicals and benzaldehyde with yields of ~ 0.07 in the case of toluene (Wu et al., 2014) and ~ 0.06 in the case of 1,2,4-TMB (Li and Wang, 2014). The OH adducts can react with atmospheric O2 via H abstraction to form ring-retaining phenolic compounds (i.e. cresols and trimethylphenols) (Jang and Kamens, 2001; Kleindienst et al., 2004). The phenol formation yield decreases for the more substituted aromatics: in case of toluene, the cresol yield is ~ 0.18 (Klotz et al., 1998; Smith et al., 1998), whereas for 1,2,4-TMB, the trimethylphenol yield is ~ 0.03 (Smith et al., 1999; Bloss et al., 2005). Both abstraction and phenolic channels lead to the formation of products retaining the aromatic ring.

Figure 1.

Major gas-phase oxidation pathways for aromatic hydrocarbons, using toluene as an example. Reaction yields for the oxidation pathways of toluene recommended by MCM v3.3.1 are shown in black (Bloss et al., 2005). The proposed yields from the present study are shown in blue. The yield of the peroxide-bicyclic pathway is calculated based on the yields of ring-scission products.

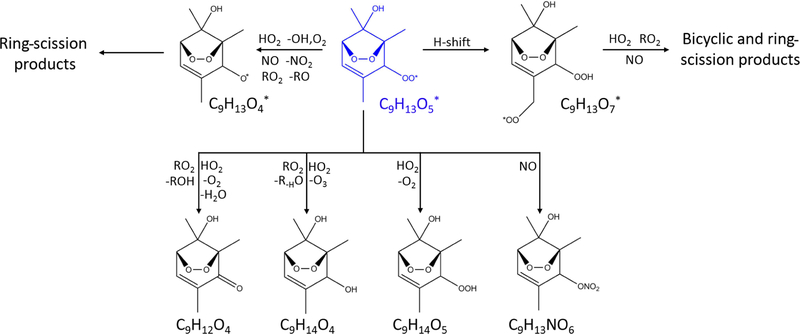

The OH adducts can also react with O2 through re-combination. In this case they lose aromaticity and form non-aromatic ring-retaining bicyclic peroxy radicals (BPRs). Under urban-relevant high-NO conditions BPRs also react with NO to form bicyclic oxy radicals that decompose to ring-scission carbonylic products such as (methyl) glyoxal and biacetyl. Recent theoretical studies have predicted new epoxy-dicarbonyl products that have not been reported in previous studies (Li and Wang, 2014, Wu et al., 2014). Reaction of BPRs with NO can also result in the formation of bicyclic organonitrates. In addition, BPRs react with HO2 and RO2, forming bicyclic hydroperoxides and bicyclic carbonyls respectively (Fig. 2). Finally, BPRs can undergo unimolecular H migration followed by O2 addition (auto-oxidation), leading to the formation of non-aromatic ring-retaining highly oxygenated organic molecules (HOMs) (Bianchi et al., 2019). Molteni et al. (2018) reported the elemental composition of the HOMs from a series of aromatic compounds produced under low-NO conditions. The auto-oxidation pathway might be more important for the substituted aromatics because of the higher yield of BPR formation and the larger number of relatively weak C–H bonds (Wang et al., 2017). Both ring-retaining and ring-scission compounds are expected to be low in volatility and contribute significantly to SOA (Schwantes et al., 2017). A number of major uncertainties remain in the model representation of the oxidation of aromatic compounds, including the overprediction of ozone concentration, the underprediction of OH production and the lack of detailed description of SOA formation (Birdsall and Elrod, 2011; Wyche et al., 2009).

Figure 2.

Oxidation pathways of bicyclic peroxy radicals in the OH-initiated oxidation of 1,2,4-trimethylbenzene. The starting radical Is shown in blue. Bimolecular reactions are from MCM v3.3.1 (Bloss et al., 2005) and Birdsall and Elrod (2011).

In the present work, we investigate detailed mechanisms of hydroxyl radical multigenerational oxidation chemistry of two aromatic hydrocarbons – toluene and 1,2,4-trimethylbenzene – under moderately high, urban-relevant NOx levels (~ 10ppbv). Laboratory experiments were conducted in an environmental chamber over approximately 1d of atmospheric-equivalent oxidation. We use three chemical ionisation mass spectrometry (CIMS) techniques (I− reagent ion, reagent ion, and H3O+ reagent ion) to characterise and quantify gas-phase oxidation products. In addition, CIMS and I− CIMS were used to detect particle-phase products. The goal of this work is to identify gas-phase pathways leading to the production of low-volatility compounds, which are important for SOA formation and support these identifications with CIMS data and a method to characterise the kinetics of an oxidation system.

2. Methods

2.1. Experimental design

All experiments were performed in a 7.5m3 Teflon environmental chamber (Hunter et al., 2014). Prior to experiments, the chamber was flushed and filled with purified air. During experiments the environmental chamber was operated in the constant-volume (“semi-batch”) mode, in which clean air (11–14Lmin−1) was constantly added to make up for instrument sample flow. The temperature of the chamber was controlled at 292±1K. All experiments were carried out under dry conditions (relative humidity, ±1%) to simplify gas- and particle-phase measurements. Higher RH can potentially shorten the lifetime of particle-phase hydroperoxides, epoxides, and organonitrates (Li et al., 2018) as well as affecting gas-particle partitioning kinetics and thermodynamics (Saukko et al., 2012).

We performed a series of photochemical experiments, in which toluene and 1,2,4-TMB were oxidised by OH (Table S1 in the Supplement). The experiments were carried out under high-NO conditions such that the fate of peroxy radicals was primarily determined by their reaction with NO (Seinfeld and Pandis, 2016). First, dry ammonium sulfate particles, used as condensation nuclei, were injected in the chamber to reach a number concentration of 2.5–5.7×104 cm−3. Seed particles were not injected into the chamber in two experiments. Hexafluorobenzene, (C6F6, which serves as a dilution tracer) was then added to the chamber. Next, nitrous acid (HONO) was injected as an OH precursor. HONO was generated in a bubbler containing a solution of sodium nitrite by adding 2–4μL of sulfuric acid via a syringe pump. Purified air that was subsequently injected at 15Lmin−1 carried HONO into the chamber, which resulted in a mixing ratio of 28–35ppbv (except for experiment 8 in which the initial HONO mixing ratio was 60ppbv). After the addition of the oxidant, the aromatic precursor (toluene or 1,2,4-TMB, Sigma-Aldrich) was added to the chamber by injecting 3μL of the precursor into a heated inlet. The initial mixing ratio of the precursor was 89ppbv in toluene experiments and 69ppbv in 1,2,4-TMB experiments. The reagents were allowed to mix for several minutes, after which the ultraviolet (UV) lights, centred at approximately 340nm, were turned on to start photolysis of HONO (resulting in the production of hydroxyl radicals and nitric oxide) and photooxidation of the precursor. During experiments, additional injections of HONO were added to the chamber in order to roughly maintain the OH levels. As a result, the mixing ratio of NO in the chamber during experiments was estimated to be ~ 0.3ppbv, whereas the NO2 mixing ratio was approximately 10ppbv (Fig. S2 in the Supplement). Measurements were conducted within several hours, corresponding to 14–16h of atmospheric-equivalent exposure (assuming an average OH concentration of 1.5×106 moleccm−3). Concentrations of O3 and HONO+NOx for a typical run are shown in Fig. S2.

2.2. Chamber instrumentation

The concentration of ozone (2B Technologies), relative humidity, and temperature were measured in the chamber. A 42i NOx monitor (Thermo Fischer Scientific) was used to measure the sum of concentrations of HONO and nitrogen oxides (NOx). Aromatic precursors as well as gas-phase oxygenated volatile organic compounds (OVOCs) were detected by chemical ionisation high-resolution time-of-flight mass spectrometry (CIMS) techniques: I− CIMS, CIMS and H3O+ CIMS. The I− CIMS instrument (Aerodyne Research Inc.) is described by Lee et al. (2014). CIMS and H3O+ CIMS were carried out using a mass spectrometer (PTR3, modes: H3O+ q(H2O)n, n = 0–1 (as PTR3 H3O+ O CIMS; IONICON Analytik) which was operated in two ionisation Breitenlechner et al., 2017) and •(H2O)n, n = 0–2 (as PTR3 CIMS; Hansel et al., 2018; Zaytsev et al., 2019). Switching between ion modes occurred every 5min. H3O+ CIMS was also conducted by a proton-transfer-reaction mass spectrometer (Vocus 2R PTR-TOF, Aerodyne Research Inc.; Krechmer et al., 2018). Each CIMS instrument used a 3/16” PFA Teflon sampling line of 1m in length with a flow of 2SLPM (standard litres per minute). The PTR3 and Vocus 2R PTR-TOF are designed to minimise inlet losses of sampled compounds (Krechmer et al., 2018; Breitenlechner et al., 2017); for more details see the Supplement. Detection efficiency and sensitivity of CIMS instruments depend critically on both the reagent ion and the measured sample molecule. The concentrations of aromatic precursors were measured by the Vocus 2R PTR-TOF, which was directly calibrated for the two compounds. Smaller, less oxidised molecules were primarily quantified by PTR-MS (PTR3 H3O+ CIMS and Vocus 2R PTR-TOF), whereas PTR3 CIMS and I− CIMS were mainly used for the detection of larger and more functionalised molecules. The PTR3 and I− CIMS instruments were directly calibrated for 10 VOCs with various functional groups (Tables S2 and S3). An average calibration factor was applied to other species detected by PTR-MS instruments, while collision–dissociation methods were implemented to constrain sensitivities of I− CIMS and CIMS (Lopez-Hilfiker et al., 2016; Zaytsev et al., 2019). Use of these methods and average calibration factors leads to uncertainties in estimated concentrations of detected compounds within a factor of 10. CIMS uncertainties are within a factor of 3, whereas I− CIMS is less certain. The majority of the analysis in this work relies on CIMS and PTR-MS data, while I− CIMS data are used as supporting measurements. Glyoxal was detected by laser-induced phosphorescence (Madison LIP; Huisman et al., 2008).

Total organic aerosol mass was measured using an Aerodyne aerosol mass spectrometer (AMS, DeCarlo et al., 2006), calibrated with ammonium nitrate and assuming a collection efficiency of 1. Particle-phase compounds were quantified using the FIGAERO-HRToF-I− CIMS (Lopez-Hilfiker et al., 2014) and a second PTR3 that could be operated in two positive modes as described above, which was equipped with an aerosol inlet comprising a gas-phase denuder and a thermal desorption unit heated to 180° (TD CIMS and TDH3O+ CIMS). At this temperature, all particles were evaporated while thermal decomposition of labile oxygenated compounds was relatively small (Zaytsev et al., 2019). Uncertainties of the particle-phase CIMS measurements are similar to the corresponding uncertainties of the gas-phase CIMS instruments.

2.3. Kinetic model

The Framework for 0-D Atmospheric Modelling v3.1 (F0AM; Wolfe et al., 2016) containing reactions from the Master Chemical Mechanism (MCM v3.3.1) (Jenkin et al., 2003; Bloss et al., 2005) was used to simulate the photooxidation of 1,2,4-TMB and toluene in the environmental chamber and to compare the modelled products with the measurements. Model calculations were constrained to physical parameters of the environmental chamber (pressure, temperature, photolysis frequencies, and dilution rate). The dilution term for volatile compounds was estimated based on the concentration of the dilution tracer, hexafluorobenzene. Injections of aromatic compounds and HONO were modelled as sources during the time of injection, and the chamber lights’ intensity was tuned to match the measured time-dependent concentration of aromatic precursors with the modelled values. As for semi- and low-volatile compounds, the wall deposition rate was estimated to be 5×10−4 s−1 using the “rapid burst” method described in detail by Krechmer et al. (2016).

2.4. Calculation of OH exposure and product yields

The OH concentration was determined using the decay of the aromatic precursor, accounting for losses from dilution. The mixing ratio of the aromatic VOC (ArVOC: toluene or 1,2,4-TMB) is given by the following kinetics equation:

| (1) |

where [ArVOC] is the time-dependent mixing ratio of the aromatic precursor, is the second-order rate constant for the ArVOC+OH reaction (ktoluene+OH = 5.63×10−12 cm3 molec−1 s−1 and k1,2,4-TMB+OH = 3.25×10−11 cm3molec−1 s−1 at 293K; Calvert et al., 2002), is the integrated OH exposure, kdilution is the unimolecular rate constant determining dilution, and t is the time since the beginning of irradiation by the UV lights.

Yields of first-generation products were determined based on the decay of the aromatic precursor, the rise of the product, and accounting for physical (dilution and chamber wall deposition) and chemical (reaction with OH, NO3, O3 and photolysis) losses. A correction procedure described in detail by Galloway et al. (2011) is applied to calculate product yields. This correction takes physical and chemical losses of products in the environmental chamber into account:

| (2) |

where is the corrected mixing ratio of the compound at measurement time i, Δt is time between measurements i and i −1, [X]i−1 is the measured product mixing ratio of measurement i −1, Δ[X]i is the observed net change in [X] that occurs over Δt, and kchemical loss and kphysical loss are the rate constants describing chemical and physical losses of the product respectively.

Yields of first-generation products were determined from the linear relationship between the amount of the corrected product formed and the amount of the primary ArVOC reacted:

| (3) |

where [X]corr is the amount of the corrected product formed, [ArVOC]reacted is the amount of the primary ArVOC reacted, and Y is the first-generation yield of the product.

2.5. Gamma kinetics parameterisation

Photooxidation products can be characterised not only by their concentration and yield, but also by their time series behaviour. In a laboratory experiment, the time series behaviour of a product is dependent on the kinetic parameters of the molecule: the relative rates of formation and reactive loss, and the number of reactions to create the product. We characterise time series behaviour of products using the gamma kinetics parameterisation (GKP), which describes kinetics of an oxidation system in terms of multigenerational chemistry. The detailed description of this parameterisation technique is given by Koss et al. (2019), so we include only a brief description here. A multigenerational hydroxyl radical oxidation system can be represented as a linear system of reactions:

| (4) |

where k is the second-order rate constant and m is the number of reactions needed to produce species Xm.

In laboratory experiments, oxidation reactions can be parameterised as a linear system of first-order reactions if reaction time t is replaced by OH exposure [OHexposure]t = . In this case, the time-dependent concentration of a compound Xm can be parameterised by (Koss et al., 2019):

| (5) |

where a is a scaling factor, k is the effective second-order rate constant (cm3 molec−1 s−1), m is the generation number, and [OHexposure]t is the integrated OH exposure (molecscm−3).

Equation (5) can be used to fit the observed concentration of a compound to return its parameters a, k, and m. The parameter m determines the number of reactions with OH needed to produce the compound, whereas the parameter k gives an approximate measure of the compound reactivity. We define “generation” here as the number of reactions with OH. At low generations (m = 1–2), the standard deviation of the fit is 0.1, while it can be higher (up to 0.8) at higher (3+) generations (Koss et al., 2019). Examples of fitted chamber measurements are shown in Fig. S3.

3. Results and discussion

Toluene and 1,2,4-TMB react with OH to form both ring-retaining (via benzaldehyde, phenolic, and bicyclic channels) and ring-scission (via bicyclic and epoxide channels) products. (These four channels are illustrated using the example of toluene in Fig. 1.) First- and later-generation gas- and particle-phase oxidation products are detected and quantified for both systems. In the following sections we compare products suggested by MCM and previous studies to corresponding molecular formulas detected by CIMS. In some cases, the ion identity is well established from previous research or because there are a limited number of reasonable structures (e.g. phenols, benzaldehydes, and ring-scission dicarbonyl products); in other cases, multiple isomers are possible, which could contribute to some differences between modelled and observed behaviour.

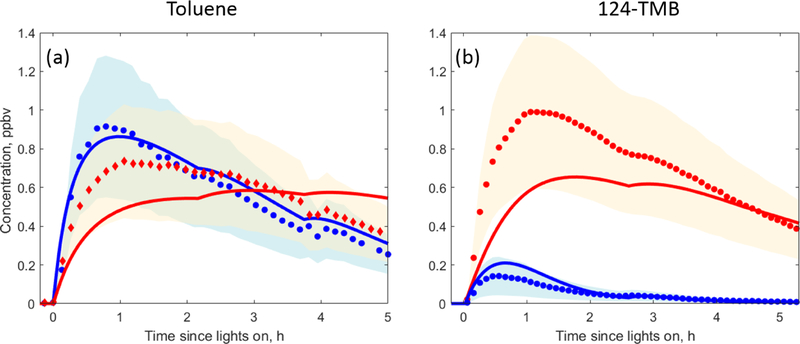

3.1. Products from benzaldehyde, phenolic, and epoxide channels

In the toluene experiments, the approximate yields of benzaldehyde and cresol (~ 0.10 and ~ 0.16 respectively) were calculated based on the decay of toluene measured by the Vocus 2R PTR-TOF, the rise of the two products measured by PTR3 H3O+ CIMS and CIMS (cresol was measured by H3O+ CIMS while CIMS was used for detecting benzaldehyde), and accounting for losses of cresol and benzaldehyde from wall deposition and reaction with OH and NO3 (Sect. 2.4). MCM v3.3.1 recommends a 0.07 yield of benzaldehyde and a 0.18 yield of cresol (total of all isomers) from OH-initiated oxidation of toluene. Benzaldehyde and cresol concentrations predicted by MCM agree within uncertainties with the PTR3 H3O+ CIMS and CIMS measurements, and the time series behaviour of measurements and kinetic model predictions is similar (Fig. 3a). In general, MCM predicts that phenolic and benzaldehyde channels are less important for more substituted aromatics (Bloss et al., 2005). Hence, the MCM-based kinetic model recommends a 0.06 yield of dimethylbenzaldehyde and a 0.03 yield of trimethylphenol from the OH-initiated oxidation of 1,2,4-TMB.The kinetic model predictions for the two products agree within uncertainties with the H3O+ CIMS measurements, and the time series behaviour is again similar (Fig. 3b). Phenols and benzaldehydes can further react within the MCM v3.3.1 scheme to form highly oxidised second-generation compounds. The importance of this pathway is discussed further in Sect. 3.2.1.

Figure 3.

MCM v3.3.1 predictions (solid lines) compared to H3O+ CIMS (circles) and CIMS (diamonds) measurements under high- NO oxidation of (a) toluene and (b) 1,2,4-TMB for phenols (red) and benzaldehydes (blue). The uncertainty in the H3O+ CIMS and CIMS measurements is shown using blue and red shading.

MCM v3.3.1 also includes an epoxy-oxy channel in which it predicts formation of non-fragmented linear epoxide-containing products (Fig. 1). The MCM-predicted yields of these species are 0.10 and 0.30 for toluene and 1,2,4-TMB systems respectively. The yields of these products observed with CIMS are significantly smaller (~ 0.01 in both systems). However, the observations are consistent with theoretical studies (Li and Wang, 2014; Wu et al., 2014) in which it has been shown that only a negligible fraction of the bicyclic radicals would break the O–O bond to form epoxide-containing products.

3.2. Products from bicyclic pathway

3.2.1. Non-fragmented, ring-retaining products

Bicyclic peroxy radicals are formed through the addition of O2 to the OH adducts (Fig. 1). Starting from a generic aromatic compound CxHy, we expect the formation of BPRs with the formula CxHy+1O5. BPRs likely react with RO2, HO2, or NO, leading to the following products (Fig. 2) (Birdsall and Elrod, 2011): bicyclic carbonyls (CxHyO4), bicyclic alcohols (CxHy+2O4), bicyclic hydroperoxides (CxHy+2O5), and bicyclic organonitrates (CxHy+1NO6), as well as alkoxy radicals (discussed later). A number of oxygenated products are detected by CIMS including C7H8O4, C7H10O5, and C7H9NO6 in the toluene experiments, and C9H12O4, C9H14O4, and C9H13NO6 in the 1,2,4-TMB experiments (Table 3). As authentic standards are not available, these compounds were quantified using a voltage scanning procedure based on collision-induced dissociation (Sect. 2.2). The majority of OVOCs with high carbon numbers were detected at the maximum sensitivity, which was experimentally determined in each photooxidation experiment and depends on operational conditions of the CIMS instrument (Zaytsev et al., 2019) (Tables S4 and S5). A number of products with the same molecular formulas corresponding to bicyclic carbonyls (C7H8O4 and C9H12O4) and alcohols (C7H10O4 and C9H14O4) were also detected by I− CIMS and PTR-MS.

Table 3.

Kinetics fit of gas-phase highly oxygenated compounds detected in toluene (top five rows) and 1,2,4-TMB (bottom seven rows) oxidation experiments.

| Product formula | Generation parameter m | Kinetic parameter k (cm3 molec−1 s−1) |

|---|---|---|

| C7H8O4 | 1.5 | 1×10−11 |

| C7H10O5 | 1.5 | 1×10−11 |

| C7H8O6 | 1.6 | 1.1×10−11 |

| C7H9NO6 | 2.1 | 0.8×10−11 |

| C7H9NO8 | 2 | 0.9×10−11 |

| C9H12O4 | 1.5 | 1.8×10−11 |

| C9H14O4 | 1.6 | 1.7×10−11 |

| C9H14O5 | 1.8 | 1.9×10−11 |

| C9H12O6 | 1.8 | 1.4×10−11 |

| C9H13NO6 | 1.4 | 1.7×10−11 |

| C9H13NO7 | 2.1 | 2.3×10−11 |

| C9H13NO8 | 2.3 | 1.8×10−11 |

In MCM v3.3.1, the bicyclic peroxy radical undergoes analogous reactions: (1) it can react with HO2 to produce a hydroperoxide; (2) it can react with RO2 to produce an alkoxy radical, an alcohol, or a carbonyl; and (3) it can react with NO to produce an alkoxy radical or a nitrate. According to MCM, under relevant urban conditions BPRs nearly exclusively react with NO and HO2 and dominantly form alkoxy radicals which further decompose to smaller ring-scission compounds (Figs. 2, S4 and S5) (Sect. 3.2.3). In this study, the approximate lifetime of BPRs, calculated as inverse reactivity, is estimated to be ~ 5s for toluene and ~ 7s for 1,2,4-TMB. MCM v3.3.1 does not include the formation of the bicyclic carbonyl, C9H12O4, in the 1,2,4-TMB oxidation scheme, whereas in the case of toluene it predicts that a major fraction of bicyclic carbonyl C7H8O4 is produced as a second-generation product from the reaction of bicyclic hydroperoxide and organonitrate with OH. In contrast, the GKP fit based on the CIMS measurements implies that a significant fraction of the detected compounds is formed in the first generation in both systems (Table 3). These first-generation bicyclic carbonyls can be produced by the reaction of BPR with HO2 or RO2. In addition, MCM predicts a higher than observed concentration of bicyclic alcohol (C9H14O4 for the 1,2,4-TMB system) as the only channel present in the MCM-based kinetic model is a reaction of BPR with RO2, although it can also be produced via the BPR+HO2 pathway (Fig. 2). Finally, MCM v3.3.1 predicts that a notable fraction of BPR reacts with HO2 to form bicyclic hydroperoxide. CIMS measurements of C9H14O5 and C7H10O5 are less than the kinetic model prediction for each chemical system but agree within measurement uncertainties. The generation number m of C7H10O5 and C9H14O5 is approximately between 1.7 and 1.8 which suggests that a compound with the same molecular formula can be produced by more than one pathway with a different number of reaction steps. Birdsall and Elrod (2011) proposed that the BPR from several aromatic precursors reacting with HO2 can form an alkoxy radical and OH. Similarly, recent studies have shown that numerous peroxy radicals do not form a hydroperoxide in unity yield while reacting with HO2 (Praske et al., 2015; Orlando and Tyndall, 2012). Hence, we observe the formation of numerous highly oxygenated compounds with molecular formulas corresponding to bicyclic carbonyls, alcohols, organonitrates, and hydroperoxides via the peroxide-bicyclic channel under high-NO conditions.

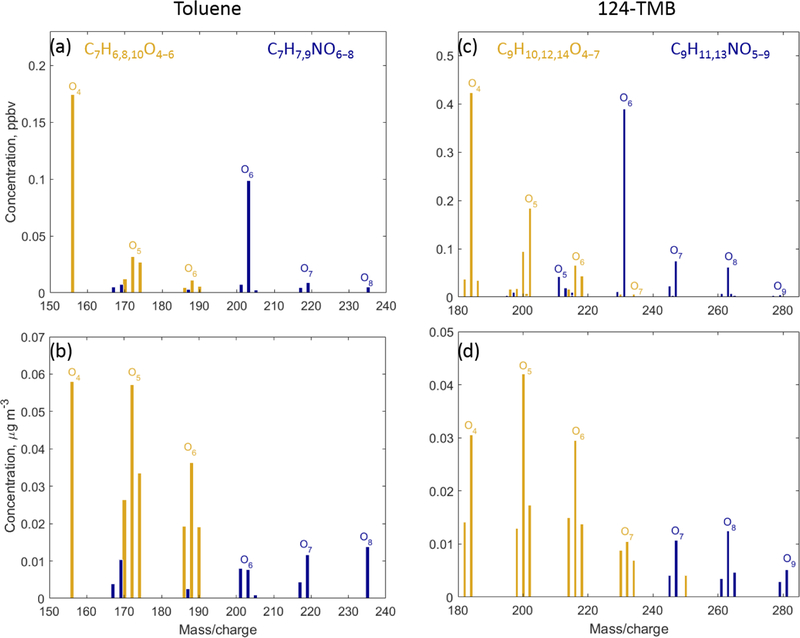

In addition to the formation of closed-shell products, bicyclic peroxy radicals can undergo isomerisation reactions to form more oxidised peroxy radicals (Fig. 2) (Wang et al., 2017; Molteni et al., 2018). These reactions are not included in MCM v3.3.1. These radicals can subsequently react with RO2, HO2, or NO leading to a series of more oxidised bicyclic products, so-called highly oxygenated molecules (HOMs): carbonyl (CxHyO6), alcohol (CxHy+2O6), hydroperoxide (CxHy+2O7), and nitrate (CxHy+1NO8). Several products with the aforementioned molecular formulas are detected by CIMS C7H9NO8 were detected by CIMS as • OVOC. (Fig. 4). In the toluene experiments, C7H8O6, C7H10O6 and In the 1,2,4-TMB experiments, C9H14O6 and C9H13NO8 were detected as • OVOC, while C9H12O6 was detected as both C9H12O6 (m/z 234.098) and as [(NH4) • (H2O) qC9H12O6]+ (m/z 252.108). The yield of molecules with a high O : C (greater than 0.44) ratio is larger in the case of 1,2,4-TMB compared with toluene. However, the gamma kinetics parameterisation suggests that none of these compounds are solely first-generation products (Table 3) which implies that there are multiple chemical pathways in which products with the same molecular formula (but potentially different structure) are formed. Some of the products can be produced in the bicyclic oxidation pathway of cresol or trimethylphenol resulting in the formation of alcohols (CxHy+2O5), hydroperoxides (CxHy+2O6) and nitrates (CxHy+1NO7). Formation of bicyclic alcohols and hydroperoxides from the phenolic channel is included in MCM v3.3.1. We conclude that although a plethora of compounds with a high O : C ratio was observed, only some of them are formed via first-generation isomerisation/auto-oxidation pathways. These findings underline the importance of phenolic and benzaldehyde channels for producing highly oxygenated compounds, especially for the less substituted aromatics given the high yields of phenols and benzaldehydes and their high reactivity.

Figure 4.

Mass spectra of compounds with high oxygen content (O : C > 0.44) from toluene (a, b) and 1,2,4-trimethylbenzene (c, d) detected by CIMS. Gas-phase mass spectra are shown in (a, c), and particle-phase mass spectra are shown in (b, d). Non-nitrogen-containing compounds are shown using yellow, and nitrogen-containing compounds are shown using blue.

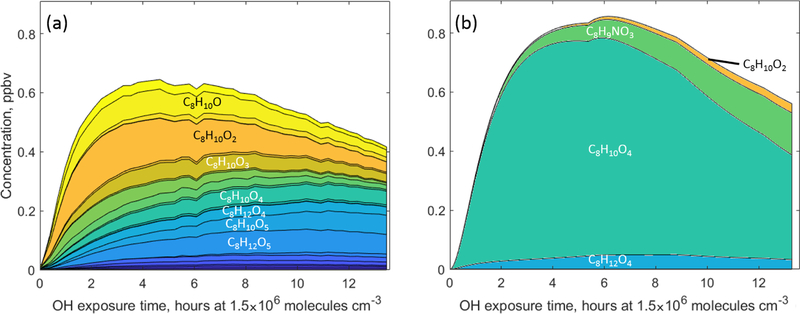

3.2.2. Fragmented ring-retaining products

In addition to non-fragmented functionalised C9 and C7 products possibly formed via the bicyclic channel, a variety of lower-carbon-containing (C8 and C6) products with fewer carbon atoms were also detected in both chemical systems. The total concentration of C8 components predicted by MCM v3.3.1 for 1,2,4-TMB is in good agreement with the CIMS and H3O+ CIMS measurements (less oxidised compounds, O : C < 0.25, were detected using H3O+ CIMS, whereas CIMS was used for more oxidised species), although the observed composition is distinctly different from the MCM prediction (Fig. 5). According to MCM, there are only four C8 products with mixing ratios at or above the parts per trillion (ppt) level. The most abundant predicted compound, bicyclic carbonyl (C8H10O4, MXYOBPEROH in MCM), is produced via the reaction of bicyclic nitrate C9H13NO6 with OH, whereas the second most abundant compound, dimethylnitrophenol (C8H9NO3, DM124OHNO2 in MCM), is formed in the benzaldehyde pathway. While all of the predicted products have been observed, CIMS and H3O+ CIMS also detect a plethora of C8 compounds not included in MCM. Furthermore, MCM only predicts a total of 0.16ppb for all C6 compounds in the toluene experiments, while the combined measured mixing ratio of 15 C6 compounds is ~ 0.5ppb (Fig. S6). The two most prominent C6 products recommended by MCM, C6H5NO3 and C6H6O2, are predicted to be formed in the benzaldehyde channel.

Figure 5.

The C8 gas-phase products (a) detected by H3O+ CIMS and CIMS and (b) predicted by MCM v3.3.1 during oxidation of 1,2,4-trimethylbenzene

There are several pathways that may lead to the formation of the fragmented ring-retaining C8 and C6 products. One of them is ipso addition followed by dealkylation (Loison et al., 2012). In their study of the dealkylation pathway in the OH-initiated oxidation of several aromatic compounds, Noda et al. (2009) showed the importance of this pathway and reported dealkylation yields of 0.054 for toluene. Similarly, Birdsall and Elrod (2011) determined a 0.047 yield of dealkylation products for toluene. Loison et al. (2012) reported a 0.02 yield of dealkylation pathway products from the hexamethylbenzene + OH reaction. However, in some studies, yields of dealkylation products have been found below 0.01 (Aschmann et al., 2010). While we cannot determine exact yields of observed dealkylation compounds as many of them are later-generation products, we estimate an overall amount of carbon of ~ 3 and ~ 5ppbC stored in C6 and C8 compounds for toluene and 1,2,4-TMB respectively, compared with 600ppbC in the system as a whole. Although observed concentrations of these products are not very high, a significant fraction (> 40%) of them are highly oxygenated products with an O : C ratio greater than 0.5. These products can effectively partition to the particle phase and contribute to SOA formation (Sect. 3.3).

3.2.3. Products from the ring-scission pathway

Recent theoretical studies suggest that the ring-scission pathway leads to a series of two ring-scission products such that the total number of carbon atoms present in the original aromatic compound is conserved in the two products (Wu et al., 2014; Li and Wang, 2014). In particular, a toluene study by Wu et al. (2014) predicted significant yields of 1,2-dicarbonyls and a range of C4 and C5 products. Those larger compounds include dicarbonyls (butenedial C4H4O2 and methylbutenedial C5H6O2), which had already been detected in previous experimental studies (Calvert et al., 2002), and newly proposed epoxy-dicarbonyl products (epoxybutanedial C4H4O3 and methylepoxybutanedial C5H6O3). As for 1,2,4-TMB, Li and Wang (2014) also predict two groups of ring-scission products: (1) smaller 1,2-dicarbonyls such as glyoxal, methylglyoxal and biacetyl and (2) larger C5, C6 and C7 products. Similar to the toluene system, those larger compounds include dicarbonyls (C5H6O2, C6H8O2, and C7H10O2), which had previously been reported in numerous studies, and new epoxy-dicarbonyl products (C5H6O3 and C6H8O3). Some experimental studies reported that larger ring-scission products were found at systematically lower yields than the corresponding 1,2-dicarbonyl products (Arey et al., 2009). This result suggests that either the product pair carbon conservation rule is not followed or that the larger products undergo further photochemical or heterogeneous degradation in the environmental chamber.

A series of dicarbonyls were experimentally detected including glyoxal and methylglyoxal in the toluene experiments, and methylglyoxal and biacetyl in the 1,2,4-TMB experiments (Tables 1 and 2). Although a relatively small amount of glyoxal (2.5ppb) is predicted to be formed from the 1,2,4-TMB+OH pathway, observed amounts of glyoxal were below the limit of detection of the Madison LIP instrument (1ppb) suggesting that the glyoxal yield does not exceed 0.03 in this system. Measured glyoxal and methylglyoxal formation yields, combined with the biacetyl yield from the 1,2,4-TMB oxidation, indicate that under high-NO conditions the first-generation yield of all 1,2-dicarbonyls is ∼ 0.43 and ∼ 0.35 for toluene and 1,2,4-TMB respectively (Tables 1 and 2). For all 1,2-dicarbonyls the observed generation number m is greater than 1 and is consistent between the two systems, which suggests that these compounds are produced by more than one pathway with different numbers of reaction steps. In addition to the aforementioned 1,2-dicarbonyls, a series of dicarbonyls with a higher carbon number was observed in both systems (Tables 1 and 2).

Table 1.

Major toluene oxidation products measured by H3O+ CIMS and CIMS.

| Product name | Product formula | Generation parameter m | Kinetic parameter k (cm3 molec−1 s−1) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Glyoxal | C2H2O2 | 1.2 | 1.3×10−11 | 28% |

| Methylglyoxal | C3H4O2 | 1.3 | 1.1×10−11 | 15% |

| Butenedial | C4H4O2 | 0.8 | 2×10−11 | 8% |

| Methylbutenedial | C5H6O2 | 0.7 | 2×10−11 | 37% |

| Epoxybutanedial | C4H4O3 | 1.3 | 1×10−11 | 5% |

| Methylepoxybutanedial | C5H6O3 | 1.3 | 1×10−11 | 5% |

| Benzaldehyde | C7H6O | 1 | 1×10−11 | 9% |

| Cresol | C7H8O | 1 | 2.3×10−11 | 10% |

| Dicarbonyl epoxide | C7H8O3 | 0.9 | 2.2×10−11 | 1% |

Table 2.

Major 1,2,4-TMB oxidation products measured by H3O+ and CIMS.

| Product name | Product formula | Generation parameter m | Kinetic parameter k (cm3 molec−1 s−1) | Yield (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Methylglyoxal | C3H4O2 | 1.3 | 1.8×10−11 | 25% |

| Biacetyl | C4H6O2 | 1.3 | 2.2×10−11 | 10% |

| Methylbutenedial | C5H6O2 | 0.7 | 3.5×10−11 | 5% |

| Dimethylbutenedial | C6H8O2 | 0.9 | 4.1×10−11 | 40% |

| Trimethylbutenedial | C7H10O2 | 1 | 5.1×10−11 | 2% |

| Methylepoxybutanedial | C5H6O3 | 1.8 | 1.9×10−11 | n/a |

| Dimethylepoxybutanedial | C6H8O3 | 1.1 | 2.4×10−11 | 2% |

| Dimethylbenzaldehyde | C9H10O | 1 | 1.4×10−11 | 3% |

| Trimethylphenol | C9H12O | 1 | 3.5×10−11 | 2% |

| Dicarbonyl epoxide | C9H12O3 | 1 | 4×10−11 | 1% |

n/a=not applicable.

For all of these species (except trimethylbutenedial) the generation number m is slightly smaller than 1. Finally, ions corresponding to newly proposed epoxy-dicarbonyl products were also observed (Tables 1 and 2). However, the generation number m for these compounds is between 1 and 2, suggesting that there are multiple pathways resulting in compounds with those molecular formulas. Overall, we observed ∼ 0.45 and ∼ 0.47 yields of larger carbonyls in the toluene and 1,2,4-TMB experiments respectively.

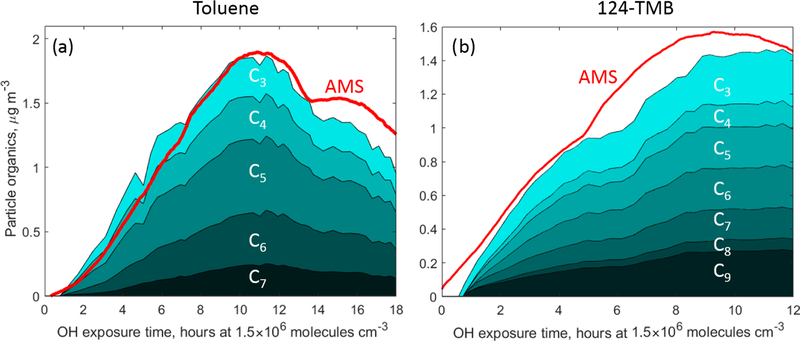

3.3. SOA analysis

The peak SOA concentration measured by CIMS was 1.8µgm−3 for the toluene oxidation experiment and 1.4µgm−3 for 1,2,4-TMB which is in good agreement with the AMS measurements (1.9 and 1.6µgm−3 respectively). Figure 6 depicts the relative distribution of carbon in the particle phase according to the carbon atom number nC for 1,2,4-TMB and toluene SOA respectively. The O : C ratios calculated from individual species measured from thermally desorbed SOA using NH+4 CIMS were ∼ 0.95 for toluene SOA and ∼ 0.7 for 1,2,4-TMB SOA. These ratios are in good agreement with the atomic O : C ratios measured by AMS (0.85 and 0.65 for toluene and 1,2,4-TMB SOA respectively) (Canagaratna et al., 2015).

Figure 6.

Total organics measured in the particle phase by CIMS and binned by the carbon atom number in (a) the toluene photooxidation experiment and (b) the 1,2,4-TMB photooxidation experiment. Total carbon measured by AMS is in red.

Products observed in the gas phase are compared to those detected in the particle phase to further understand the mechanism of SOA formation from aromatics precursors. A variety of ring-retaining products were observed in the particle phase for oxidation of 1,2,4-TMB and toluene: non-fragmented products (e.g. C9H12O4−6 for 1,2,4-TMB and C7H8O4−6 for toluene) and fragmentary products (e.g. C8H10O4−5 and C7H8O4−5 for 1,2,4-TMB and C6H6O4−5 for toluene). The same non-fragmentary ring-retaining oxidation products, detected by NH+4 CIMS in the gas phase and expected to be low in volatility, are detected in the particle phase (Fig. 4). Overall, ring-retaining products make up a significant fraction of the total 1,2,4-TMB SOA mass (∼ 25% for 1,2,4-TMB SOA and ∼ 30% for toluene SOA) (Fig. 6), even though the total concentration of these products in the gas phase is relatively small (∼ 2ppb for 1,2,4-TMB and ∼ 1ppb for toluene). Furthermore, numerous species corresponding to those of the ring-scission products were detected including C5H8O3, C4H6O3, and C3H4O2. It is likely that the concentration of larger ring-retaining products in the particle phase is underestimated due to their thermal fragmentation in the desorption unit inlet of the CIMS instrument (Zaytsev et al., 2019), although it should be noted that many highly oxygenated compounds were detected, e.g. C7H6O6 and C9H10O7. These findings underscore the importance of bicyclic, phenolic, and benzaldehyde channels for producing ring-retaining highly oxygenated compounds that comprise a significant fraction of SOA (more than 25%).

4. Conclusions and implications for the aromatic oxidation mechanism

In the present work, we studied the multigenerational photooxidation of two aromatic compounds (toluene and 1,2,4-trimethylbenzene) in an environmental chamber under relevant urban high-NO conditions. We identified a number of oxidation products based on their molecular formula and determined yields for certain first-generation products. We provided kinetic and mechanistic information on numerous products using a gamma kinetics parameterisation fit.

We compare and contrast observed products with predictions from the Master Chemical Mechanism (MCM v3.3.1), which provides explicit representation of chemical reactions that constitute the overall aromatic oxidation mechanism on the basis of the extensive body of existing experimental work. Laboratory studies are a vital support for the mechanism, and the agreement between these studies and the MCM output is one of the important criteria demonstrating the accuracy of the kinetic model prediction. MCM accurately predicts the overall presence and importance of the three major channels for the primary OH-initiated oxidation of aromatic compounds (peroxide-bicyclic, benzaldehyde, and phenolic). However, the epoxy-oxy channel appears to be overpredicted by the MCM-based kinetic model. In both systems we observed a variety of stable bicyclic products which underlines the importance of the bicyclic channel in the oxidation of aromatic compounds (Fig. 1). MCM correctly predicts the greater importance of the bicyclic pathway for the more substituted aromatics, although the speciated fate of BPRs is not entirely consistent with observations. In addition to bicyclic organonitrates, carbonyls and alcohols, we detect numerous compounds with molecular formulas corresponding to bicyclic hydroperoxides, which suggests that this class of products may be formed in the oxidation of aromatic molecules even under high-NO conditions. Recent studies (Molteni et al., 2018; Wang et al., 2017) suggest that bicyclic peroxy radicals can undergo isomerisation and auto-oxidation reactions, leading to the formation of HOMs. Furthermore, Molteni et al. (2018) report that the HOM yields from various aromatics are relatively uniform and are not linked to bicyclic peroxy radical or phenol formation yields. Here, we observe the formation of highly oxygenated compounds with a high O : C ratio (of up to 1.1) in both systems. However, the abundance of these compounds is greater in the case of 1,2,4-TMB for which the yield of the bicyclic peroxy radicals is higher (Fig. 4). Moreover, the observed kinetics of these compounds suggests that they might be produced by more than one pathway, including both the isomerisation/auto-oxidation reactions and further oxidation of phenols and benzaldehydes. Many of these compounds are low in volatility and comprise a significant fraction (more than 25%) of SOA mass, which was measured using AMS and TD- CIMS and the two measurements are in good agreement. These findings emphasise the significance of ring-retaining highly oxygenated products for SOA formation and provide further evidence that isomerisation and auto-oxidation reactions can be fast enough to compete with bimolecular reactions with NO and HO2 even under high-NO conditions (in this study the total BPR loss rate is estimated to be ∼ 0.1–0.2s−1; Figs. S4 and S5). A plethora of fragmentary ring-retaining products is observed in the gas phase in both systems, many of which are not present in the MCM, which underlines the importance of the fragmentation pathway in the oxidation of aromatic compounds. Numerous ring-scission products are detected, including C2–C7 dicarbonyls and C4−6H4−8O3 products, possibly epoxydicarbonyls. The kinetics of the ring-scission products (e.g. generation number m) is consistent between the two systems, which suggests that many of those carbonyls are produced in more than one pathway with a differing number of reaction steps with OH, and those pathways are similar between different aromatic systems.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements.

This work was supported by the Harvard Global Institute, the NSF award (AGS-1638672), and a Core Center grant (grant no. P30-ES002109) from the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences, National Institutes of Health. Abigail R. Koss acknowledges support from the Dreyfus Postdoctoral Program. Martin Breitenlechner acknowledges support from the Austrian science fund (FWF; grant J-3900).

Financial support. This research has been supported by the Harvard Global Institute, the National Science Foundation (grant no. AGS-1638672), the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (grant no. P30-ES002109), and the Austrian Science Fund (grant no. J-3900).

Footnotes

Data availability. Data used within this work are available upon request. Please email Alexander Zaytsev (zaytsev@g.harvard.edu).

Supplement. The supplement related to this article is available online at: https://doi.org/10.5194/acp-19–15117-2019-supplement.

Competing interests. The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Review statement. This paper was edited by Alexander Laskin and reviewed by two anonymous referees.

References

- Arey J, Obermeyer G, Aschmann SM, Chattopadhyay S, Cusick RD, and Atkinson R: Dicarbonyl Products of the OH Radical-Initiated Reaction of a Series of Aromatic Hydrocarbons, Environ. Sci. Technol, 43, 683–689, 10.1021/es8019098, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aschmann SM, Arey J, and Atkinson R: Extent of Hatom abstraction from OH+p-cymene and upper limits to the formation of cresols from OH+m-xylene and OH+p-cymene, Atmos. Environ, 44, 3970–3975, 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2010.06.059, 2010. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bianchi F, Kurtén T, Riva M, Mohr C, Rissanen MP, Roldin P, Berndt T, Crounse JD, Wennberg PO, Mentel TF, Wildt J, Junninen H, Jokinen T, Kulmala M, Worsnop DR, Thornton JA, Donahue N, Kjaergaard HG, and Ehn M: Highly Oxygenated Organic Molecules (HOM) from Gas-Phase Autoxidation Involving Peroxy Radicals: A Key Contributor to Atmospheric Aerosol, Chem. Rev, 119, 3472–3509, 10.1021/acs.chemrev.8b00395, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birdsall AW and Elrod MJ: Comprehensive NO-Dependent Study of the Products of the Oxidation of Atmospherically relevant Aromatic Compounds, J. Phys. Chem. A, 115, 5397–5407, 10.1021/jp2010327, 2011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bloss C, Wagner V, Jenkin ME, Volkamer R, Bloss WJ, Lee JD, Heard DE, Wirtz K, Martin-Reviejo M, Rea G, Wenger JC, and Pilling MJ: Development of a detailed chemical mechanism (MCMv3.1) for the atmospheric oxidation of aromatic hydrocarbons, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 5, 641–664, 10.5194/acp-5-641-2005, 2005. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Breitenlechner M, Fischer M, Hainer M, Heinritzi M, Curtius M, and Hansel A: PTR3: An instrument for Studying the Lifecycle of Reactive Organic Carbon in the Atmosphere, Anal. Chem, 89, 5824–5831, 10.1021/acs.analchem.6b05110, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calvert J, Atkinson R, Becker KH, Kamens R, Seinfeld J, Wallington T, and Yarwood G: The mechanisms of atmospheric oxidation of aromatic hydrocarbons, Oxford University Press, Inc., New York, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Canagaratna MR, Jimenez JL, Kroll JH, Chen Q, Kessler SH, Massoli P, Hildebrandt Ruiz L, Fortner E, Williams LR, Wilson KR, Surratt JD, Donahue NM, Jayne JT, and Worsnop DR: Elemental ratio measurements of organic compounds using aerosol mass spectrometry: characterization, improved calibration, and implications, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 15, 253–272, 10.5194/acp-15-253-2015, 2015. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeCarlo PF, Kimmel JR, Trimborn A, Northway MJ, Jayne JT, Aiken AC, Gonin M, Fuhrer K, Horvath T, Docherty KS, Worsnop DR, and Jimenez JL: Field-Deployable, High-Resolution, Time-ofFlight Aerosol Mass Spectrometer, Anal. Chem, 78, 8281–8289, 10.1021/ac061249n, 2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Galloway MM, Huisman AJ, Yee LD, Chan AWH, Loza CL, Seinfeld JH, and Keutsch FN: Yields of oxidized volatile organic compounds during the OH radical initiated oxidation of isoprene, methyl vinyl ketone, and methacrolein under high-NOx conditions, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 11, 10779–10790, 10.5194/acp-11-10779-2011, 2011. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hansel A, Scholz W, Mentler B, Fischer L, and Berndt T: Detection of RO2 radicals and other products from + cyclohexene ozonolysis with NH4 and acetate ionization mass spectrometry, Atmos. Environ, 186, 248–255, 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2018.04.023, 2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hu D, Bian QJ, Li TWY, Lau AKH, and Yu JZ: Contributions of isoprene, monoterpenes, beta-caryophyllene, and toluene to secondary organic aerosols in Hong Kong during the summer of 2006, J. Geophys. Res.-Atmos, 113, D22206, 10.1029/2008JD010437, 2008. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Huisman AJ, Hottle JR, Coens KL, DiGangi JP, Galloway MM, Kammrath A, and Keutsch FN: Laser-Induced Phosphorescence for the in Situ Detection of Glyoxal at Part per Trillion Mixing Ratios, Anal. Chem, 80, 5884–5891, 10.1021/ac800407b, 2008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hunter JF, Carrasquillo AJ, Daumit KE, and Kroll JH: Secondary Organic Aerosol Formation from Acyclic, Monocyclic, and Polycyclic Alkanes, Environ. Sci. Technol, 48, 10227–10234, 10.1021/es502674s, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang M and Kamens RM: Characterization of Secondary Aerosol from the Photooxidation of Toluene in the Presence of NOx and 1-Propene, Environ. Sci. Technol, 35, 3626–3639, 10.1021/es010676+, 2001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenkin ME, Saunders SM, Wagner V, and Pilling MJ: Protocol for the development of the Master Chemical Mechanism, MCM v3 (Part B): tropospheric degradation of aromatic volatile organic compounds, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 3, 181–193, 10.5194/acp-3-181-2003, 2003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kleindienst TE, Conver TS, McIver CD, and Edney EO: Determination of Secondary Organic Aerosol Products from the Photooxidation of Toluene and their Implications in Ambient PM2.5, J. Atmos. Chem, 47, 79–100, 10.1023/B:JOCH.0000012305.94498.28, 2004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Klotz B, Sorensen S, Barnes I, Becker K-H, Etzkorn T, Volkamer R, Platt U, Wirtz K, and Martin-Reviejo M: Atmospheric Oxidation of Toluene in a Large-Volume Outdoor Photoreactor: In Situ Determination of Ring-Retaining Product Yields, J. Phys. Chem. A, 102, 10289–10299, 10.1021/jp982719n, 1998. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Koss AR, Canagaratna M, Zaytsev A, Krechmer JE, Breitenlechner M, Nihill KJ, Lim CY, Rowe JC, Roscioli JR, Keutsch FN, and Kroll JH: Dimensionality-reduction techniques for complex mass spectrometric datasets: application to laboratory atmospheric organic oxidation experiments, Atmos. Chem. Phys. Discuss, , 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krechmer JE, Pagonis D, Ziemann PJ, and Jimenez JL: Quantification of Gas-Wall Partitioning in Teflon Environmental Chambers Using Rapid Bursts of Low-Volatility Oxidized Species Generated in Situ, Environ. Sci. Technol 50, 5757–5765, 10.1021/acs.est.6b00606, 2016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krechmer JE, Lopez-Hilfiker F, Koss A, Hutterli M, Stoermer C, Deming B, Kimmel J, Warneke C, Holzinger R, Jayne J, Worsnop D, Fuhrer K, Gonin M, and de Gouw J: Evaluation of a New Vocus Reagent-Ion Source and Focusing Ion-Molecule Reactor for use in Proton-TransferReaction Mass Spectrometry, Anal. Chem, 90, 12011–12018, 10.1021/acs.analchem.8b02641, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee BH, Lopez-Hilfiker FD, Mohr C, Kurten T, Worsnop DR, and Thornton J: An iodide-adduct high-resolution time-offlight chemical-ionization mass spectrometer: Application to atmospheric organic and inorganic compounds, Environ. Sci. Technol, 48, 6309–6317, 10.1021/es500362a, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li L, Tang P, Nakao S, and Cocker III DR: Impact of molecular structure on secondary organic aerosol formation from aromatic hydrocarbon photooxidation under low-NOx conditions, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 16, 10793–10808, 10.5194/acp-16-10793-2016, 2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Li Y and Wang L: The atmospheric oxidation mechanism of 1,2,4-trimethylbenzene initiated by OH radicals, Phys. Chem. Chem. Phys, 16, 17908–17917, 10.1039/c4cp02027h, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z, Smith KA, and Cappa CD: Influence of relative humidity on the heterogeneous oxidation of secondary organic aerosol, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 18, 14585–14608, 10.5194/acp-18-14585-2018, 2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Loison J-C, Rayez M-T, Rayez J-C, Gratien A, Morajkar P, Fittschen C, and Villenave E: Gas-Phase Reaction of Hydroxyl Radical with Hexamethylbenzene, J. Phys. Chem. A, 116, 12189–12197, 10.1021/jp307568c, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Hilfiker FD, Mohr C, Ehn M, Rubach F, Kleist E, Wildt J, Mentel Th. F., Lutz A, Hallquist M, Worsnop D, and Thornton JA: A novel method for online analysis of gas and particle composition: description and evaluation of a Filter Inlet for Gases and AEROsols (FIGAERO), Atmos. Meas. Tech, 7, 983–1001, 10.5194/amt-7-983-2014, 2014. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lopez-Hilfiker FD, Iyer S, Mohr C, Lee BH, D’Ambro EL, Kurtén T, and Thornton JA: Constraining the sensitivity of iodide adduct chemical ionization mass spectrometry to multifunctional organic molecules using the collision limit and thermodynamic stability of iodide ion adducts, Atmos. Meas. Tech, 9, 1505–1512, 10.5194/amt-9-1505-2016, 2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Molteni U, Bianchi F, Klein F, El Haddad I, Frege C, Rossi MJ, Dommen J, and Baltensperger U: Formation of highly oxygenated organic molecules from aromatic compounds, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 18, 1909–1921, 10.5194/acp18-1909-2018, 2018. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Noda J, Volkamer R, and Molina MJ: Dealkylation of Alkylbenzenes: A Significant Pathway in the Toluene, o-, m-, pXylene+OH Reaction, J. Phys. Chem. A, 113, 9658–9666, 10.1021/jp901529k, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orlando JJ and Tyndall GS: Laboratory studies of organic peroxy radical chemistry: an overview with emphasis on recent issues of atmospheric significance, Chem. Soc. Rev, 41, 6294–6317, 10.1039/c2cs35166h, 2012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Praske E, Crounse JD, Bates KH, Kurtén T, Kjaergaard HG, and Wennberg PO: Atmospheric Fate of Methyl Vinyl Ketone: Peroxy Radical Reactions with NO and HO2, J. Phys. Chem. A, 119, 4562–4572, 10.1021/jp5107058, 2015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saukko E, Lambe AT, Massoli P, Koop T, Wright JP, Croasdale DR, Pedernera DA, Onasch TB, Laaksonen A, Davidovits P, Worsnop DR, and Virtanen A: Humidity-dependent phase state of SOA particles from biogenic and anthropogenic precursors, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 12, 7517–7529, 10.5194/acp-12-7517-2012, 2012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schwantes RH, Schilling KA, McVay RC, Lignell H, Coggon MM, Zhang X, Wennberg PO, and Seinfeld JH: Formation of highly oxygenated low-volatility products from cresol oxidation, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 17, 3453–3474, 10.5194/acp-17-3453-2017, 2017. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seinfeld JH and Pandis SN: Atmospheric Chemistry and Physics: From Air Pollution to Climate Change, Wiley, Hoboken, NJ, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Smith DF, McIver CD, and Kleindienst TE: Primary Product Distribution from the Reaction of Hydroxyl Radicals with Toluene at ppb NOx Mixing Ratios, J. Atmos. Chem., 30, 209–228, 10.1023/A:1005980301720, 1998. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith DF, Kleindienst TE, and McIver DF: Primary Product Distributions from the Reaction of OH with m-, p-Xylene, 1,2,4- and 1,3,5-Trimethylbenzene, J. Atmos. Chem, 34, 339–364, 10.1023/A:1006277328628, 1999. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tang JH, Chan LY, Chan CY, Li YS, Chang CC, Wang XM, Zou SC, Barletta B, Blake DR, and Wu D: Implications of changing urban and rural emissions on non-methane hydrocarbons in the Pearl River Delta region of China, Atmos. Environ, 42, 3780–3794, 10.1016/j.atmosenv.2007.12.069, 2007. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Wu R, Berndt T, Ehn M, and Wang L: Formation of Highly Oxidized Radicals and Multifunctional Products from the Atmospheric Oxidation of Alkylbenzenes, Environ. Sci. Technol, 51, 8442–8449, 10.1021/acs.est.7b02374, 2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfe GM, Marvin MR, Roberts SJ, Travis KR, and Liao J: The Framework for 0-D Atmospheric Modeling (F0AM) v3.1, Geosci. Model Dev, 9, 3309–3319, 10.5194/gmd9-3309-2016, 2016. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wu R, Pan S, Li Y, and Wang L: Atmospheric Oxidation Mechanism of Toluene, J. Phys. Chem. A, 118, 4533–4547, 10.1021/jp500077f, 2014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wyche KP, Monks PS, Ellis AM, Cordell RL, Parker AE, Whyte C, Metzger A, Dommen J, Duplissy J, Prevot ASH, Baltensperger U, Rickard AR, and Wulfert F: Gas phase precursors to anthropogenic secondary organic aerosol: detailed observations of 1,3,5-trimethylbenzene photooxidation, Atmos. Chem. Phys, 9, 635–665, 10.5194/acp-9635-2009, 2009. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zaytsev A, Breitenlechner M, Koss AR, Lim CY, Rowe JC, Kroll JH, and Keutsch FN: Using collision-induced dissociation to constrain sensitivity of ammonia chemical ionization mass spectrometry (NH4 CIMS) to oxygenated volatile organic compounds, Atmos. Meas. Tech, 12, 1861–1870, 10.5194/amt-12-1861-2019, 2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zheng J, Shao M, Che W, Zhang L, Zhong L, Zhang Y, and Streets D: Speciated VOC emission inventory and spatial patterns of ozone formation potential in the Pearl River Delta, China, Environ. Sci. Technol, 43, 8580–8586, 10.1021/es901688e, 2009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.