Abstract

Background

Gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone agonist (GnRHa) is commonly used to switch off (down regulate) the pituitary gland and thus suppress ovarian activity in women undergoing in vitro fertilisation (IVF). Other fertility drugs (gonadotrophins) are then used to stimulate ovulation in a controlled manner. Among the various types of pituitary down regulation protocols in use, the long protocol achieves the best clinical pregnancy rate. The long protocol requires GnRHa administration until suppression of ovarian activity occurs, within approximately 14 days. GnRHa can be used either as daily low‐dose injections or through a single injection containing higher doses of the drug (depot). It is unclear which of these two forms of administration is best, and whether single depot administration may require higher doses of gonadotrophins.

Objectives

To compare the effectiveness and safety of a single depot dose of GHRHa versus daily GnRHa doses in women undergoing IVF.

Search methods

We searched the following databases: Cochrane Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group Trials Register (searched July 2012), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2012, Issue 7), MEDLINE (1966 to July 2012), EMBASE (1980 to July 2012) and LILACS (1982 to July 2012). We also screened the reference lists of articles.

Selection criteria

We included RCTs comparing depot and daily administration of GnRHa for long protocols in IVF treatment cycles in couples with any cause of infertility, using various methods of ovarian stimulation. The primary review outcomes were live birth or ongoing pregnancy, clinical pregnancy and ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS). Other outcomes included number of oocytes retrieved, miscarriage, multiple pregnancy, number of gonadotrophin (FSH) units used for ovarian stimulation, duration of gonadotrophin treatment, cost and patient convenience.

Data collection and analysis

Two review authors independently selected studies, extracted data and assessed study quality. For dichotomous outcomes, we calculated odds ratios (ORs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) per woman randomised. Where appropriate, we pooled studies.

Main results

Sixteen studies were eligible for inclusion (n = 1811 participants), 12 (n = 1366 participants) of which were suitable for meta‐analysis. No significant heterogeneity was detected.

There were no significant differences between depot GnRHa and daily GnRHa in live birth/ongoing pregnancy rates (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.31, seven studies, 873 women), but substantial differences could not be ruled out. Thus for a woman with a 24% chance of achieving a live birth or ongoing pregnancy using daily GnRHa injections, the corresponding chance using GnRHa depot would be between 18% and 29%.

There was no significant difference between the groups in clinical pregnancy rate (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.23, 11 studies, 1259 women). For a woman with a 30% chance of achieving clinical pregnancy using daily GnRHa injections, the corresponding chance using GnRHa depot would be between 25% and 35%.

There was no significant difference between the groups in the rate of severe OHSS (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.29 to 2.42, five studies, 570 women), but substantial differences could not be ruled out. For a woman with a 3% chance of severe OHSS using daily GnRHa injections, the corresponding risk using GnRHa depot would be between 1% and 6%.

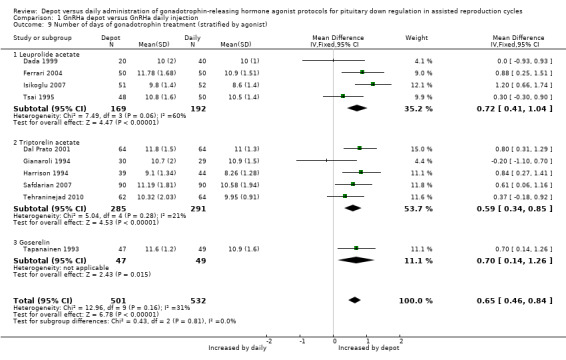

Compared to women using daily GnRHa, those on depot administration required significantly more gonadotrophin units for ovarian stimulation (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.26, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.43, 11 studies, 1143 women) and a significantly longer duration of gonadotrophin use (mean difference (MD) 0.65, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.84, 10 studies, 1033 women).

Study quality was unclear due to poor reporting. Only four studies reported live births as an outcome and only five described adequate methods for concealment of allocation.

Authors' conclusions

We found no evidence of a significant difference between depot and daily GnRHa use for pituitary down regulation in IVF cycles using the long protocol, but substantial differences could not be ruled out. Since depot GnRHa requires more gonadotrophins and a longer duration of use, it may increase the overall costs of IVF treatment.

Keywords: Female; Humans; Pregnancy; Delayed‐Action Preparations; Delayed‐Action Preparations/administration & dosage; Down‐Regulation; Drug Administration Schedule; Fertility Agents, Female; Fertility Agents, Female/administration & dosage; Fertilization in Vitro; Fertilization in Vitro/methods; Gonadotropin‐Releasing Hormone; Gonadotropin‐Releasing Hormone/agonists; Live Birth; Ovary; Ovary/physiology; Ovulation Induction; Ovulation Induction/methods; Pituitary Gland; Pituitary Gland/drug effects; Pituitary Gland/physiology; Pregnancy Rate; Randomized Controlled Trials as Topic

Plain language summary

Gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone agonist for improving fertility

Women undergoing in vitro fertilisation (IVF) need to take a series of hormones. The use of the drug GnRHa (gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone agonist) during one stage of this process increases the chance of pregnancy. There are several options for GnRHa use. Long courses of GnRHa can be given either as daily low‐dose injections, or using a single higher‐dose longer‐acting injection (depot version). The review of 16 randomised controlled trials found no evidence that depot versus daily GnRHa injections produce different rates of live birth/ongoing pregnancy, clinical pregnancy or ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS). However, substantial differences could not be ruled out. For example, for a woman with a 25% chance of achieving a live birth or ongoing pregnancy using GnRHa depot, the corresponding chance using daily injection would be between 16% and 30%. For a woman with a 25% risk of severe OHSS using GnRHa depot, the corresponding risk using daily injection would be between 4% and 89%. For a woman with a 25% chance of achieving a live birth or ongoing pregnancy using daily GnRHa injections, the corresponding chance using a depot injection would be between 19% and 30% . For a woman with a 25 % chance of severe OHSS using daily GnRHa injections, the corresponding chance using GnRHa depot would be between 9 % and 45 % . Depot GnRHa may increase the cost of an IVF cycle, because it lengthens the period to ovulation and requires the use of higher doses of other hormone drugs. The quality of the studies was unclear due to poor reporting, and only four studies reported live births.

Summary of findings

Summary of findings for the main comparison. GnRHa depot compared to GnRHa daily injection for pituitary down regulation in assisted reproduction cycles.

| GnRHa depot compared to GnRHa daily injection for pituitary down regulation in assisted reproduction cycles | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with pituitary down regulation in assisted reproduction cycles Settings: outpatients Intervention: GnRHa depot Comparison: GnRHa daily injection | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| GnRHa daily injection | GnRHa depot | |||||

| Live birth/ongoing pregnancy rate per woman Delivery of one or more living infants/pregnancy beyond 12 weeks of gestation | 24 per 100 | 23 per 100 (181 to 292) | OR 0.95 (0.7 to 1.31) | 873 (7 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2,3 | No differences in the results were detected on sensitivity analysis for adequate allocation concealment. OR 0.95 (0.64 to 1.41). 514 participants in 4 studies. |

| Clinical pregnancy rate per woman Identified by the presence of a gestational sac on ultrasonography or histopathological confirmation of trophoblast tissue | 30 per 100 | 29 per 100 (25 to 35) | OR 0.96 (0.75 to 1.23) | 1259 (11 studies) | ⊕⊕⊕⊝ moderate1 | No differences in the results were detected on sensitivity analysis for adequate allocation concealment. OR 0.96 (0.68 to 1.37). 574 participants in 5 studies. |

| OHSS incidence rates | 3 per 100 | 2 per 100 (1 to 6) | OR 0.84 (0.29 to 2.42) | 570 (5 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2,3 | |

| Miscarriage rates | 13 per 100 | 14 per 100 (9 to 22) | OR 1.16 (0.7 to 1.94) | 512 (9 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2,3 | |

| Number of oocytes retrieved | The mean number of oocytes retrieved in the control groups was 8 to 14 | The mean number of oocytes retrieved in the intervention groups was 0.11 higher (0 to 0.23 higher) | 1142 (11 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

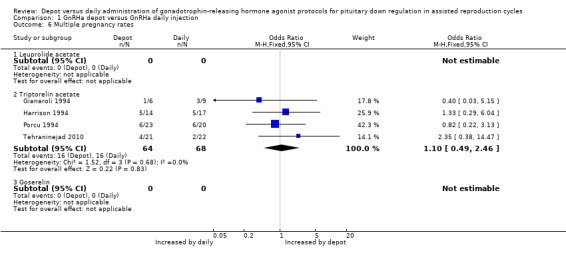

| Multiple pregnancy rates | 24 per 100 | 25 per 100 (13 to 43) | OR 1.1 (0.49 to 2.46) | 132 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2,3 | |

| Number of gonadotropin (FSH) units employed | The mean number of gonadotrophin (FSH) units employed in the control groups was 1260 to 3448 IU | The mean number of gonadotrophin (FSH) units employed in the intervention groups was 0.18 standard deviations higher (0.06 to 0.3 higher) | 1043 (11 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,4 | No statistical differences were detected for depot versus daily leuprolide acetate and goserelin. Only in the subgroup of triptorelin acetate depot GnHRa was increased: SMD 0.2 (0.04 to 0.37). | |

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; FSH: follicle‐stimulating hormone; GnRHa: gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone agonist; IU: international units; OHSS: ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome; OR: odds ratio; RR: risk ratio; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Most of the studies were classified as unclear risk of bias for all domains. 2 Total number of events is fewer than 300. 3 Number of studies is insufficient to assess publication bias. 4 Considerable differences detected in standard deviations among studies.

Summary of findings 2. Different doses of GnRHa depot compared to GnRHa daily injection for pituitary down regulation in assisted reproduction cycles.

| Different doses of GnRHa depot compared to GnRHa daily injection for pituitary down regulation in assisted reproduction cycles | ||||||

| Patient or population: patients with pituitary down regulation in assisted reproduction cycles Settings: outpatients Intervention: different doses of GnRHa depot Comparison: GnRHa daily injection | ||||||

| Outcomes | Illustrative comparative risks* (95% CI) | Relative effect (95% CI) | No of participants (studies) | Quality of the evidence (GRADE) | Comments | |

| Assumed risk | Corresponding risk | |||||

| GnRHa daily injection | Different doses of GnRHa depot | |||||

| Number of gonadotrophin (FSH) units employed ‐ half dose | The mean number of gonadotrophin (FSH) units employed in the control groups using half dose ranged from 1942 to 3448 IU | The mean number of gonadotrophin (FSH) units employed in the intervention groups using half dose was 0.24 standard deviations higher (0.11 lower to 0.6 higher) | 616 (5 studies) | ⊕⊝⊝⊝ very low1,2,3 | SMD 0.24 (‐0.11 to 0.6) | |

| Number of gonadotrophin (FSH) units employed ‐ full dose | The mean number of gonadotrophin (FSH) units employed in the control groups using full dose ranged from 1260 to 3195 IU | The mean number of gonadotrophin (FSH) units employed in the intervention groups using full dose was 0.28 standard deviations higher (0.11 to 0.45 higher) | 527 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,3 | SMD 0.28 (0.11 to 0.45) | |

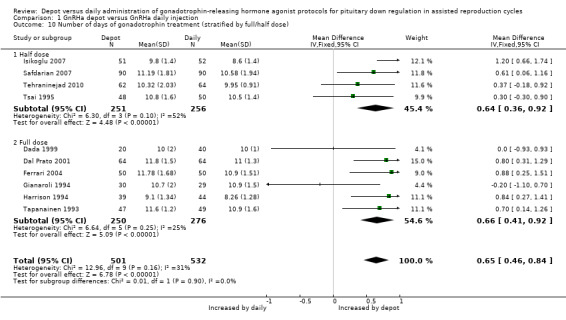

| Number of days of gonadotrophin treatment ‐ half dose | The mean number of days of gonadotrophin treatment in the control groups using half dose ranged from 8.6 to 10.58 days | The mean number of days of gonadotrophin treatment in the intervention groups using half dose was 0.64 higher (0.36 to 0.92 higher) | 507 (4 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| Number of days of gonadotrophin treatment ‐ full dose | The mean number of days of gonadotrophin treatment in the control groups using full dose ranged from 8.26 to 10.9 days | The mean number of days of gonadotrophin treatment in the intervention groups using full dose was 0.66 higher (0.41 to 0.92 higher) | 526 (6 studies) | ⊕⊕⊝⊝ low1,2 | ||

| *The basis for the assumed risk (e.g. the median control group risk across studies) is provided in footnotes. The corresponding risk (and its 95% confidence interval) is based on the assumed risk in the comparison group and the relative effect of the intervention (and its 95% CI). CI: confidence interval; FSH: follicle‐stimulating hormone; GnRHa: gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone agonist; IU: international units; SMD: standardised mean difference | ||||||

| GRADE Working Group grades of evidence High quality: Further research is very unlikely to change our confidence in the estimate of effect. Moderate quality: Further research is likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and may change the estimate. Low quality: Further research is very likely to have an important impact on our confidence in the estimate of effect and is likely to change the estimate. Very low quality: We are very uncertain about the estimate. | ||||||

1 Most of the studies were classified as having an unclear risk of bias for all domains. 2 Unexplained heterogeneity. 3 Considerable differences detected in standard deviations among studies.

Background

Description of the condition

Ovulation is regulated by the pituitary gland which is located near the base of the skull (hypothalamus). In vitro fertilisation requires that ovulation occurs in a controlled manner which facilitates retrieval of the mature eggs. In order to prevent uncontrolled or premature ovulation, drugs are used to 'switch off' (down regulate) the pituitary gland. Drugs commonly used for this purpose are gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone agonists (GNRHa). These drugs mimic the action of naturally produced gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone, but are more powerful. GNRHa causes a temporary rapid increase in the production of two other hormones (luteinising hormone (LH) and follicle‐stimulating hormone (FSH)), but after this brief surge the pituitary gland stops production and ovulation is prevented. Controlled ovulation is then stimulated by use of synthetic gonadotrophins. One of the most common side effects of fertility drugs is ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS), which can cause the ovaries to become swollen and painful.

Description of the intervention

Gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone (GnRH) is the main hypothalamic regulator for reproductive functions. In 1971, Andrew Schally and Roger Guillemin were the first to isolate, identify and synthesise GnRH, a discovery that earned them the Nobel Prize. The first step to increase GnRH activity (and thus create GNRHa) was to substitute the last peptide in the C‐terminal zone, glycine (Gly 10), by an ethylamine fused with proline, resulting in an agonist five times more potent than the original structure (Vickery 1987). The second major modification was to substitute the glycine in position 6 for a D‐aminoacid, thus reducing its enzymatic degradation. The substitution of several amino acids from the initial composition was the next step in the development of agonists with higher receptor affinity, reduced renal elimination and that were more resistant to proteolytic degradation (Néstor 1984).

How the intervention might work

Gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone agonists (GnRHa) have been widely used in cycles of in vitro fertilisation (IVF). In 1980, Rabin and McNeil (Rabin 1980) described the chance finding that continuous administration of GnRHa induced a state of down regulation of the pituitary gland, a condition that is similar to hypopituitarism in the reproductive axis, and consequently to hypogonadism. This finding opened new possibilities for clinicians who had been facing many difficulties in the treatment of women submitted to ovulation induction for IVF. Undoubtedly, one of the greatest frustrations was the occurrence of spontaneous onset of ovulation produced by the endogenous peak of LH, probably due to high estradiol levels, brought on by the use of clomiphene citrate or gonadotrophins (Van Uem 1986).

In addition to avoiding spontaneous ovulation by inhibiting the LH peak, which was the main objective of the IVF cycle (Porter 1984), several authors reported that the use of GnRHa increased the number of follicles retrieved, decreased cancelled cycle rates and led to a substantial increase in pregnancy rates (Fleming 1986; Meldum 1989; Testart 1993)

Among the various existing protocols for ovarian stimulation using GnRHa, the long protocol is associated with the best clinical pregnancy rate, according to a Cochrane review (Maheshwari 2011). The long protocol consists of GnRHa administration until the suppression of ovarian activity is evident, within approximately 14 days, at which time gonadotrophin administration can be initiated. The long protocol is subdivided into two types: one in which GnRHa administration starts on the first day of the cycle (follicular phase long protocol), and another in which it is administered in the middle of the previous luteal cycle (luteal phase long protocol).

In the IVF long protocol cycle there are two forms of GnRHa administration that can be used for pituitary down regulation: daily low‐dose injections or a single higher long‐acting dose (depot) of GnRHa. The main difference between these two approaches is in the GnRHa composition. GnRH analogues are synthetic peptide hormones conjugated to biodegradable polymers that are degraded in a regular and progressive way. These drugs are usually administered parenterally, either though subcutaneous or intramuscular injections. The onset and duration of effect of the drug depends on the molecular weight of the compound. Sustained‐release formulations consist of microcapsules containing several layers of a polymer matrix which degrade at different times, thus ensuring the continuous release of the active principle (Sanders 1984).

Why it is important to do this review

There is controversy as to which form of GnRHa administration is the most effective and safe. As pointed out by Oyesanya 1995, the use of a single dose of GnRHa would be more comfortable for women, eliminating the need for multiple injections and thereby facilitating this phase of IVF. On the other hand, Herman 1992 reported that depot GnRHa produced more intense corpus luteum inhibition, thus increasing miscarriage rates. Vauthier 1989 showed that cycles using depot GnRHa required more gonadotrophin for ovarian stimulation. In addition, they also observed lower estradiol levels and lower cleavage rates of pre‐embryos. However, these findings were not confirmed by the randomised study performed by Porcu 1994.

Although GnRHa has been used in IVF cycles for more than 10 years, there are still questions about which form of administration should be used (daily doses or a single depot dose) and consequently a more detailed analysis of the effectiveness and safety of GnRHa protocols is needed.

Objectives

To compare the effectiveness and safety of a single depot dose of GHRHa versus daily GnRHa doses in women undergoing in vitro fertilisation.

Methods

Criteria for considering studies for this review

Types of studies

Published and unpublished randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were eligible for inclusion.

We excluded non‐randomised studies (e.g. studies with evidence of inadequate sequence generation, such as alternate days), as they are associated with a high risk of bias. We also excluded cross‐over studies, as they are not a valid design in this context.

Types of participants

Couples with any cause of infertility undergoing IVF treatment cycles in combination with ovarian stimulation with human follicle‐stimulating hormone (hFSH) and/or human menopausal gonadotropin (hMG) and/or recombinant follicle‐stimulating hormone (rFSH) in IVF treatment cycles.

Biochemical pregnancies (i.e. those with only serologic confirmation) were not included in the analysis.

Types of interventions

Pituitary down regulation using depot GnRHa versus daily GnRHa in long protocols.

Long protocol is defined as GnRHa administration in either the follicular phase or in the middle of the previous luteal cycle until suppression of ovarian activity occurs.

Types of outcome measures

Primary outcomes

Live birth (defined as the delivery of one or more living infants) or ongoing pregnancy (defined as a pregnancy beyond 12 weeks of gestation) rate per woman (with preference given to live birth, where reported).

Clinical pregnancy rate per woman (clinical pregnancy is identified by the presence of a gestational sac on ultrasound or histopathological confirmation of trophoblast tissue, in the event of a miscarriage or ectopic pregnancy).

Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) rate per woman.

Secondary outcomes

Number of oocytes retrieved per woman

Miscarriage rate per pregnancy (miscarriage of any cause)

Multiple pregnancy rate per pregnancy

Cost analysis

Patient convenience

Number of gonadotrophin (FSH) units employed per cycle

Number of days of gonadotrophin treatment per cycle

Search methods for identification of studies

We searched for all published and unpublished RCTs in any available language comparing pituitary down regulation with depot GnRHa in long protocols versus pituitary down regulation with daily GnRHa doses in long protocols. Searching was originally performed in 1999. We performed an updated search in July 2012. Our search was performed in consultation with the Cochrane Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group Trials Search Co‐ordinator.

Electronic searches

For the identification of relevant studies, we developed detailed search strategies for each specific database. These were based on the search strategy developed for MEDLINE (OVID) and revised appropriately for each database. We searched the following databases: Cochrane Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group Trials Register (searched July 2012), Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2012, Issue 7), MEDLINE (1966 to July 2012), EMBASE (1980 to July 2012) and LILACS (1982 to July 2012). See Appendices for more details on search strategies. We searched these databases using the following subject headings and keywords: gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone agonist depot, fertilization in vitro, pituitary down regulation, leuprolide, goserelin, triptorelin, nafarelin, buserelin.

Searching other resources

We also searched the citation lists of relevant publications, review articles and included studies. We will perform updates at least once every two years. Even if no substantive new evidence is found and no major amendment is indicated, the date of the latest search for evidence will be made clear in this section of the review.

Data collection and analysis

We analysed data using Review Manager 5.1 (RevMan 2011).

Selection of studies

For the 2012 update, two review authors (LETA and LT) independently screened the titles and abstracts retrieved by the search strategy and selected the trials to be included in the review. Disagreements were settled by a third review author (MCRMA). We contacted study authors to clarify study eligibility or other details.

Data extraction and management

Two review authors independently extracted data from eligible studies (LETA and CRM). Review authors were not masked to the report authors, journals, date of publication, sources of financial support or results. Any disagreements were resolved through discussion or by seeking the opinion of a third review author. Data extracted included study characteristics and outcome data. For studies with more than one publication, we used the main trial report as a reference and derived additional details from secondary papers.

Assessment of risk of bias in included studies

Two review authors (LETA and CRM) independently assessed the included studies for risk of bias, using the Cochrane 'Risk of bias' assessment tool. We assessed the following domains: allocation (random sequence generation and allocation concealment); blinding of participants, personnel and outcome assessors; completeness of outcome data; selective reporting and other bias.

Measures of treatment effect

For dichotomous data (e.g. live birth rates) we used the numbers of events in the two groups to calculate Mantel‐Haenszel odds ratios (ORs). For continuous data (e.g. number of treatment days) we calculated standard mean differences (SMDs) or mean differences (MDs) between treatment groups. All outcomes are reported with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Unit of analysis issues

We analysed the primary outcomes per woman randomised. The outcomes miscarriage and multiple pregnancy were reported per pregnancy.

Some of the included studies reported our primary outcomes using other units of analysis (e.g. per cycle, per embryo transfer). These data were not included in the review because they referred only to selected subsets of participants, such as those who underwent repeated cycles, or those who underwent embryo transfer.

We reported and pooled the review outcomes number of gonadotrophin units used and number of days of gonadotrophin treatment, because all women underwent one treatment cycle. The studies that performed more than one cycle per woman were not included in the meta‐analyses.

Dealing with missing data

As far as possible, we analysed data on an intention‐to‐treat basis and made attempts to obtain missing data from the original trial lists. Where data were unavailable, we only analysed the available data.

Assessment of heterogeneity

We evaluated whether the clinical and methodological characteristics of the included studies were sufficiently similar for meta‐analysis to provide a clinically meaningful summary. We assessed statistical heterogeneity using the I2 statistic and the Chi2 test with P < 0.01 indicating significant heterogeneity.

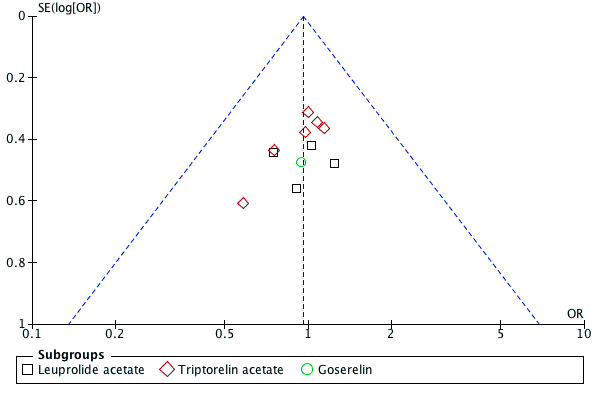

Assessment of reporting biases

In view of the difficulty of detecting and correcting for publication bias and other reporting biases, we aimed to minimise their potential impact by undertaking a comprehensive search for eligible studies and by paying attention to data duplication. We planned to use a funnel plot to explore the possibility of publication bias if sufficient studies (10 or more) were found for any of the primary analyses.

Data synthesis

If studies were sufficiently similar, we combined them using a fixed‐effect Mantel‐Haenszel model. We planned to use a random‐effects model if there was statistically significant heterogeneity. We stratified analyses according to the type of agonist used.

Subgroup analysis and investigation of heterogeneity

We conducted subgroup analysis to explore the effects of type of agonist. We also explored the effects of co‐intervention on the outcome clinical pregnancy.

For this 2012 update, we included the subgroup analysis of standard‐dose versus half‐dose GnRHa depot. The goal of this new subgroup analysis was to try to identify if lower doses of GnRHa depot caused less down regulation, and therefore would lead to the use of less gonadotrophin (FSH) units and fewer days of ovulation induction in IVF cycles.

If significant heterogeneity was detected, we planned to explore clinical differences between the studies by grouping them as follows:

-

By cause of infertility

Male infertility

Tubal factor

-

By type of ovulation induction

Human follicle‐stimulating hormone (hFSH)

Human menopausal gonadotropin (hMG)

Recombinant follicle‐stimulating hormone (rFSH)

Any association of these medications for ovulation induction

Sensitivity analysis

We conducted sensitivity analyses for the primary outcomes according to study quality, limiting analyses to studies that reported adequate allocation concealment. For the 2012 update, we also conducted a sensitivity analysis to examine the effect of pooling live birth and ongoing pregnancy data.

If significant heterogeneity had been detected, we planned to perform the following additional sensitivity analyses.

Excluding unpublished studies

Excluding studies published only as abstracts

Results

Description of studies

Results of the search

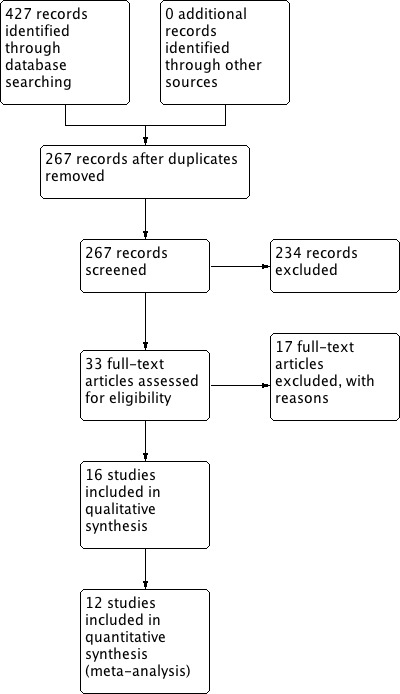

The 2012 search retrieved 427 citations. After screening the titles and abstracts of these citations, we selected 33 for full‐text reading, of which 17 were excluded and 16 matched the selection criteria and were included in the review (see Figure 1 for details of the study selection process). Seven new studies were included in this updated version of the 2004 systematic review (Ferrari 2004; Hsieh 2008; Isikoglu 2007; Porcu 1994; Porcu 1995; Safdarian 2007; Tehraninejad 2010). The review authors wrote to seven study authors to obtain more details on study characteristics and methodological quality that were unclear in the article. Only three of those contacted answered our enquiries (Dada 1999; Isikoglu 2007; Tsai 1995). However, the answers provided by Tsai were not sufficient to clarify our questions. See the tables Characteristics of included studies; Characteristics of excluded studies.

1.

Study flow diagram.

Included studies

Sixteen studies met the selection criteria (Dada 1999; Dal Prato 2001; Devreker 1996; Dor 2000; Ferrari 2004; Gianaroli 1994; Harrison 1994; Hsieh 2008; Isikoglu 2007; Librati 1996; Porcu 1994; Porcu 1995; Safdarian 2007; Tapanainen 1993; Tehraninejad 2010; Tsai 1995), but four studies were not suitable for meta‐analysis due to inappropriate reporting of data (Devreker 1996; Dor 2000; Librati 1996; Porcu 1995).

Study design and setting

Sixteen parallel‐design randomised controlled trials (RCTs) were included in the review. They randomised a total of 1811 women. Only 12 studies reported data suitable for meta‐analysis.

Participants

All participants were women undergoing IVF.

Interventions

Pituitary down regulation

Single depot dose of GHRHa

Seven studies used long‐acting leuprolide acetate to induce pituitary down regulation (Dada 1999; Ferrari 2004; Hsieh 2008; Isikoglu 2007; Librati 1996; Porcu 1995; Tsai 1995). Dada 1999, Ferrari 2004, Librati 1996 and Porcu 1995 used 3.75 mg (full dose); Tsai 1995, Hsieh 2008 and Isikoglu 2007 used 1.88 mg (half dose).

Eight studies used long‐acting triptorelin acetate (Dal Prato 2001; Devreker 1996; Dor 2000; Gianaroli 1994; Harrison 1994; Porcu 1994; Safdarian 2007; Tehraninejad 2010). Dal Prato 2001, Devreker 1996, Gianaroli 1994 and Porcu 1994 used 3.75 mg injections; Safdarian 2007 and Tehraninejad 2010 used a half dose (1.88 mg), Dor 2000 used 3.2 mg and Harrison 1994 used 3.0 mg to induce pituitary down regulation.

One study used 3.6 mg goserelin depot injections for pituitary down regulation (Tapanainen 1993).

Daily dose of GHRHa

Nine studies reported the use of short‐acting buserelin acetate for pituitary down regulation in the control group (Dada 1999; Devreker 1996; Dor 2000; Gianaroli 1994; Harrison 1994; Porcu 1995; Safdarian 2007; Tapanainen 1993; Tehraninejad 2010). However, there were differences regarding dosage and route of administration (see Characteristics of included studies ).

Dada 1999 also used nafarelin in the control group. The results of both short‐acting GnRHa groups used in this study (buserelin and nafarelin) were combined for the meta‐analysis.

Three studies used daily injections of triptorelin acetate in the control group (Dal Prato 2001; Librati 1996; Porcu 1994). Librati 1996 and Porcu 1994 used 0.1 mg/day and Dal Prato 2001 started with 0.1 mg daily and reduced the dose to 0.05 mg when ovulation induction started.

Daily injections of leuprorelin acetate for pituitary down regulation were reported by four studies (Ferrari 2004; Hsieh 2008; Isikoglu 2007; Tsai 1995). Ferrari 2004, Hsieh 2008 and Tsai 1995 used 0.5 mg/day, and Isikoglu 2007 started with 0.5 mg daily and decreased to 0.25 mg at ovulation induction.

Ovarian stimulation

Three studies used recombinant FSH for ovarian stimulation (Ferrari 2004; Hsieh 2008; Isikoglu 2007).

Five studies (Harrison 1994; Safdarian 2007; Tapanainen 1993; Tsai 1995; Tehraninejad 2010) used hMG for ovarian stimulation.

Six studies used hpFSH for ovarian stimulation (Dada 1999; Dal Prato 2001; Devreker 1996; Dor 2000; Porcu 1994; Porcu 1995).

One study stimulated the ovaries with a combination of HMG and hpFSH (Gianaroli 1994).

One study used hpFSH for ovarian stimulation in some participants and HMG in other women (Librati 1996).

Co‐interventions

Five studies reported co‐intervention with intracytoplasmic sperm injection (ICSI) (Dal Prato 2001; Hsieh 2008; Isikoglu 2007; Safdarian 2007; Tehraninejad 2010).

Outcomes

Primary outcomes

Five studies reported live birth rate (Dor 2000; Gianaroli 1994; Harrison 1994; Porcu 1994; Tapanainen 1993), but only four w ere included in the meta‐analysis. Four reported ongoing pregnancy (Dal Prato 2001; Devreker 1996; Isikoglu 2007; Tapanainen 1993), 13 reported clinical pregnancy rate (Dada 1999; Dal Prato 2001; Devreker 1996; Dor 2000; Ferrari 2004; Gianaroli 1994; Harrison 1994; Isikoglu 2007; Porcu 1994; Safdarian 2007; Tapanainen 1993; Tehraninejad 2010; Tsai 1995) and only five reported OHSS (Gianaroli 1994; Hsieh 2008; Safdarian 2007; Tapanainen 1993; Tehraninejad 2010).

Dor 2000 randomised 48 women (24 in each group), but report data only for women who underwent oocyte retrieval; data are presented in percentages and the number of occurrences do not match. Two of the studies (Devreker 1996; Porcu 1995) reported no data per randomised woman. Devreker 1996 randomised 100 couples and 33 of them received a second cycle. The results reported in the study were for 133 cycles. Porcu 1995 randomised 117 women, yet published data on 126 cycles, leading to the impression that some women received more than one cycle. The analysis of more than one cycle per participant can result in a greater possibility of eventual biases.

Librati 1996 randomised 180 women and states that 20 of them withdrew. However, the only reason for withdrawal given by the author was that the participants did not obtain at least one embryo for transfer, which can be interpreted as an exclusion and not a withdrawal. Moreover, the author does not provide means and standard deviations, nor standard errors and all results are in percentages, making it difficult to know the exact number of occurrences.

Secondary outcomes

Fifteen studies reported the number of oocytes retrieved per woman (Dada 1999; Dal Prato 2001; Devreker 1996; Dor 2000; Ferrari 2004; Gianaroli 1994; Harrison 1994; Hsieh 2008; Isikoglu 2007; Librati 1996; Porcu 1994; Safdarian 2007; Tapanainen 1993; Tehraninejad 2010; Tsai 1995).

Miscarriage rate per pregnancy was reported by 13 studies (Dada 1999; Dal Prato 2001; Devreker 1996; Dor 2000; Gianaroli 1994; Harrison 1994; Hsieh 2008; Isikoglu 2007; Librati 1996; Porcu 1994; Safdarian 2007; Tapanainen 1993; Tehraninejad 2010).

Only two of the studies reported multiple pregnancy rates (Gianaroli 1994; Harrison 1994) and none reported patient convenience or cost. Other secondary outcomes of interest were reported by most of the studies.

One study reported side effects (Tapanainen 1993).

Sixteen studies reported the number of gonadotrophin (FSH) units employed per cycle (Dada 1999; Dal Prato 2001; Devreker 1996; Dor 2000; Ferrari 2004; Gianaroli 1994; Harrison 1994; Hsieh 2008; Isikoglu 2007; Librati 1996; Porcu 1994; Porcu 1995; Safdarian 2007; Tapanainen 1993; Tehraninejad 2010; Tsai 1995).

The number of days of gonadotrophin treatment per cycle was reported by 14 studies (Dada 1999; Dal Prato 2001; Devreker 1996; Dor 2000; Ferrari 2004; Gianaroli 1994; Harrison 1994; Isikoglu 2007; Porcu 1994; Porcu 1995; Safdarian 2007; Tapanainen 1993; Tehraninejad 2010; Tsai 1995).

For the same reasons mentioned in the primary outcomes, four studies (Devreker 1996; Dor 2000; Librati 1996; Porcu 1995) were not included in the meta‐analyses.

One study (Porcu 1994) reported the number of gonadotrophin (FSH) units employed per cycle and the number of days of gonadotrophin treatment per cycle only for women who went on to embryo transfer. Since women who did not have embryos transferred may have used too much or little gonadotrophin for ovulation induction by analogue type, either depot or daily protocol, it is impossible to evaluate them.

Excluded studies

Seventeen studies were excluded: see Characteristics of excluded studies.

Nine studies were not randomised controlled trials (Devroey 1994; Insler 1991; Lipitz 1989; Lorusso 2004; Oyesanya 1995; Ron‐El 1992; Schmutzler 1988; Sonntag 2005; Vauthier 1989).

Another two studies, identified as quasi‐randomised controlled trials, were also excluded (Geber 2002; Gonen 1991).

Two studies compared a group of women that used depot GnRHa with a group without GnRHa (Lopes 1986; Yang 1991).

One study (Dicker 1991) compared two different protocols for pituitary down regulation: one using depot GnRHa versus a control group that used depot GnRHa plus daily agonist concomitantly. Fábregues (Fábregues 1998) compared an ultra‐long protocol (four months using depot GnRHa before the IVF cycle) versus a long protocol. Hazout (Hazout 1993) compared an ultra‐short protocol (seven days using daily GnRHa starting on the second day of the cycle) versus a long protocol. Parinaud (Parinaud 1992) compared two short‐acting GnRHa.

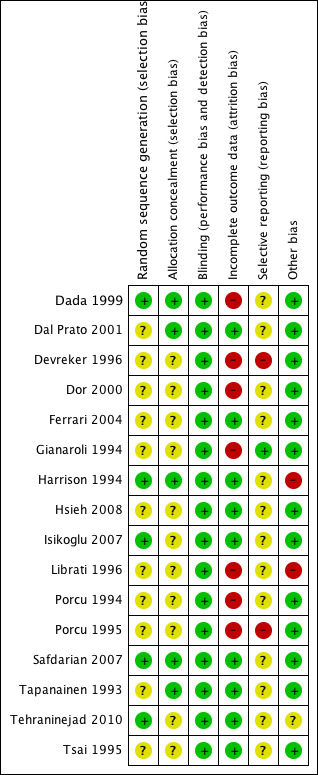

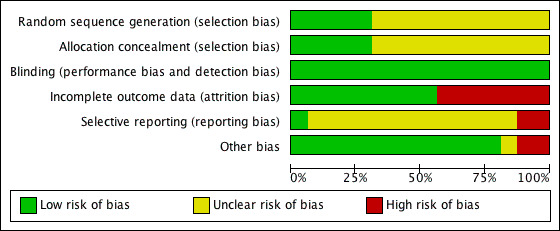

Risk of bias in included studies

2.

'Risk of bias' summary: review authors' judgements about each methodological quality item for each included study.

3.

'Risk of bias' graph: review authors' judgements about each risk of bias item presented as percentages across all included studies.

Allocation

Random sequence generation

Five studies reported acceptable methods of sequence generation and we classified them as having a low risk of bias for this domain. Three studies used a computer list (Harrison 1994; Isikoglu 2007; Safdarian 2007) and two studies used a random table (Dada 1999; Tehraninejad 2010). The other 11 studies did not report what methods were used and we classified them as having an unclear risk of bias.

Allocation concealment

Five studies were at low risk of bias for allocation concealment. Four used consecutively numbered, opaque, sealed envelopes (Dada 1999; Dal Prato 2001; Safdarian 2007; Tapanainen 1993) and one used a remotely located pharmacy for allocation concealment (Harrison 1994). Eleven studies were at unclear risk of bias because they did not report the allocation concealment method used (Devreker 1996; Dor 2000; Ferrari 2004; Gianaroli 1994; Hsieh 2008; Isikoglu 2007; Librati 1996; Porcu 1994; Porcu 1995; Tehraninejad 2010; Tsai 1995).

Blinding

Due to the nature of the primary outcomes of this review, it appears unlikely that lack of blinding was a source of bias, and we rated all studies as having a low risk of bias for this domain. In one study (Safdarian 2007) participants were kept blinded to the study drug and were instructed on how to prepare and administer the drug. No other studies reported blinding of participants, investigators or evaluators. Since the routes of administration and numbers of ampoules are different, it would have been very difficult to have participants and investigators blinded. We classified all 16 studies as having a low risk of bias for this domain.

Incomplete outcome data

Nine studies were at low risk of bias for incomplete outcome data, because all randomised women were included in the analysis or withdrawals were few and reasons were reported (Dal Prato 2001; Ferrari 2004; Harrison 1994; Hsieh 2008; Isikoglu 2007; Safdarian 2007; Tapanainen 1993; Tehraninejad 2010; Tsai 1995).

Seven studies were at high risk of bias for incomplete outcome data because they did not report the number of withdrawals (Dada 1999; Devreker 1996; Dor 2000; Gianaroli 1994; Librati 1996; Porcu 1994; Porcu 1995).

Selective reporting

Gianaroli 1994 was the only study that reported live birth, clinical pregnancy and OHSS (the primary outcomes of this review).

Thirteen studies were at unclear risk for selective reporting because they failed to report at least one of the following outcomes: live birth, ongoing pregnancy, clinical pregnancy or OHSS (the primary outcomes of this review) (Dada 1999; Dal Prato 2001; Dor 2000; Ferrari 2004; Harrison 1994; Hsieh 2008; Isikoglu 2007; Librati 1996; Porcu 1994; Safdarian 2007; Tapanainen 1993; Tehraninejad 2010; Tsai 1995).

Two studies were at high risk of bias because they reported none of the primary outcomes of this review (Devreker 1996; Porcu 1995).

Other potential sources of bias

One study (Tehraninejad 2010) was at unclear risk of bias due to inequality of the groups at baseline. There was a significant difference in the mean age of participants in the two groups, and older women tend to require more gonadotrophins for ovulation induction.

Librati 1996 was classified as having a high risk of bias due to the reasons already mentioned in 'Primary outcomes', and we considered Harrison 1994 as being at high risk of bias because it was funded by a pharmaceutical industry.

No other potential sources of bias were identified for the remaining 14 studies, which we classified as having a low risk of bias. Although most studies reported birth and pregnancy rates per cycle rather than per woman randomised, these data were not included in this review and were not regarded as a source of bias.

Across the studies, most information came from studies with an unclear risk of bias.

Effects of interventions

1 Gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone agonist (GnRHa) depot versus daily GnRHa administration

Primary outcomes

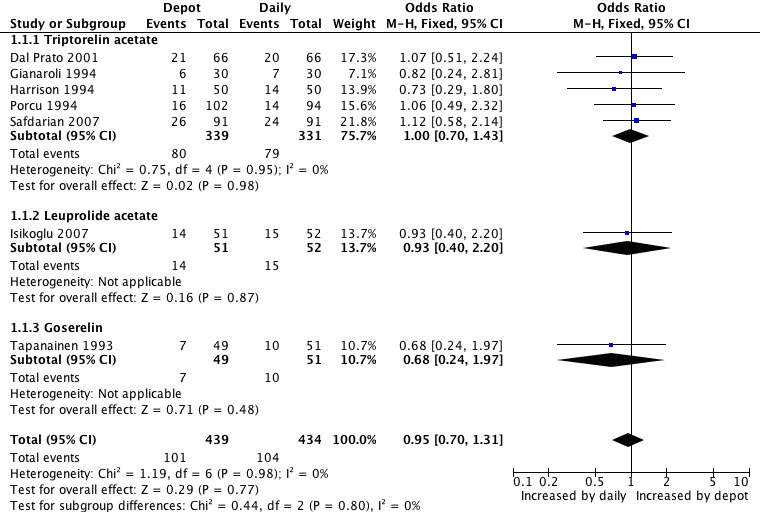

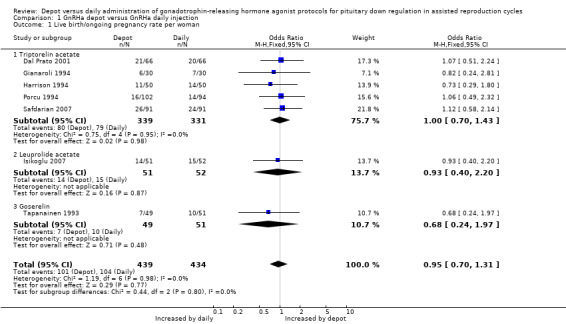

1.1 Live birth/ongoing pregnancy rates

Only four studies reported the primary outcome of live birth (Gianaroli 1994; Harrison 1994; Porcu 1994; Tapanainen 1993). There were no significant differences between the two groups (odds ratio (OR) 0.84, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.52 to 1.35, 100 women).

When these studies were pooled with four studies reporting ongoing pregnancy (Dal Prato 2001; Gianaroli 1994; Harrison 1994; Isikoglu 2007; Porcu 1994; Safdarian 2007; Tapanainen 1993) the combined ongoing pregnancy/live birth rate per woman was not significantly different in the 101/439 (23.0%) women using depot GnRHa than in the 104/434 (23.9%) women using daily GnRHa (OR 0.95, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.31, Figure 4; Analysis 1.1). There was no significant heterogeneity in this comparison (test for heterogeneity: Chi² = 1.19, df = 6, P = 0.98; I² = 0%).

4.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 GnRHa depot versus GnRHa daily injection, outcome: 1.1 Live birth/ongoing pregnancy rate per woman.

1.1. Analysis.

Comparison 1 GnRHa depot versus GnRHa daily injection, Outcome 1 Live birth/ongoing pregnancy rate per woman.

This means that for a woman with a 24% chance of achieving a live birth or ongoing pregnancy using daily GnRHa injections, the corresponding chance using GnRHa depot would be between 18% and 29%.

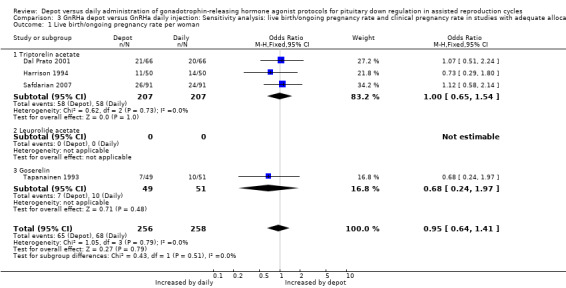

There were no significant differences between the studies according to type of agonist. Findings did not differ in the four studies that reported adequate allocation concealment (Dal Prato 2001; Harrison 1994; Safdarian 2007; Tapanainen 1993) (Analysis 3.1).

3.1. Analysis.

Comparison 3 GnRHa depot versus GnRHa daily injection: Sensitivity analysis: live birth/ongoing pregnancy rate and clinical pregnancy rate in studies with adequate allocation concealment, Outcome 1 Live birth/ongoing pregnancy rate per woman.

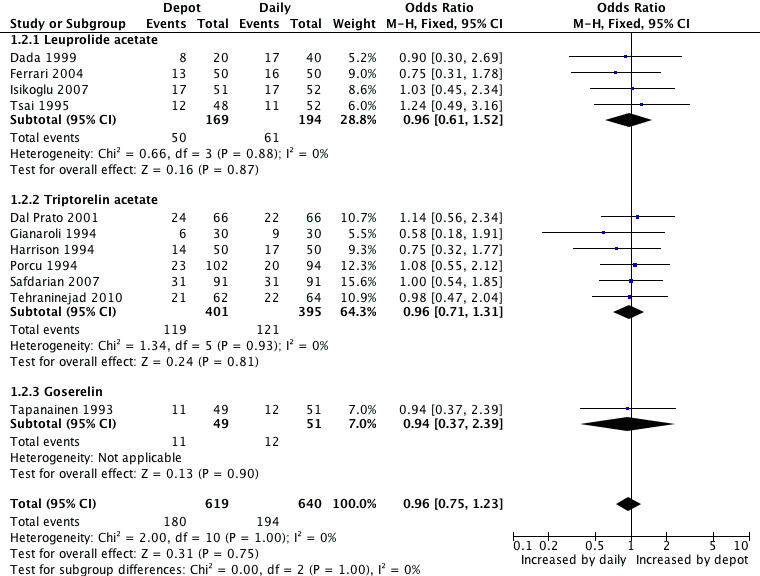

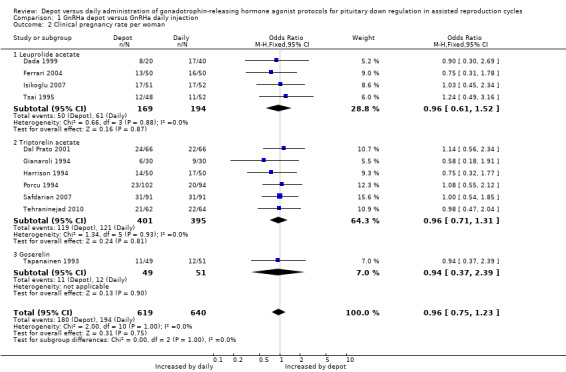

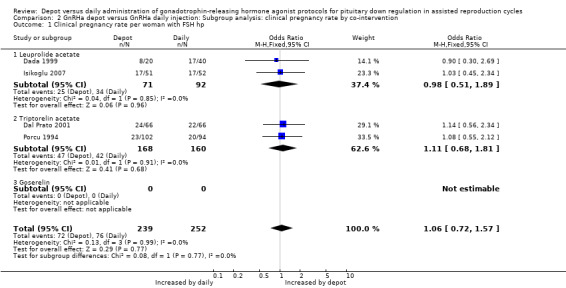

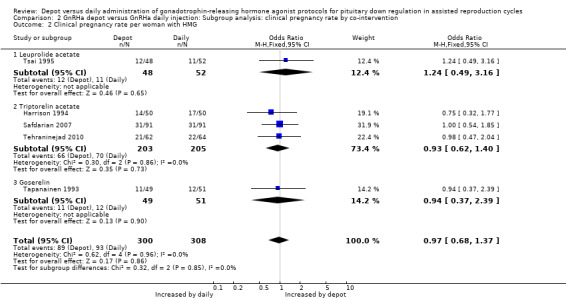

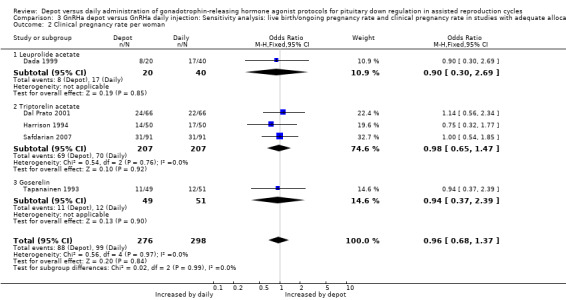

1.2 Clinical pregnancy rate per woman Eleven studies were included (Dada 1999; Dal Prato 2001; Ferrari 2004; Gianaroli 1994; Harrison 1994; Isikoglu 2007; Porcu 1994; Safdarian 2007; Tapanainen 1993; Tehraninejad 2010; Tsai 1995). The pregnancy rate per woman did not differ significantly in the 180/619 (29.0%) women using depot GnRHa compared to the 194/640 (30.3%) women using daily GnRHa (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.23, Figure 5; Analysis 1.2). There was no statistical heterogeneity in this comparison (test for heterogeneity: Chi² = 2.00, df = 10, P = 1.00; I² = 0%).

5.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 GnRHa depot versus GnRHa daily injection, outcome: 1.2 Clinical pregnancy rate per woman.

1.2. Analysis.

Comparison 1 GnRHa depot versus GnRHa daily injection, Outcome 2 Clinical pregnancy rate per woman.

This means that for a woman with a 30% chance of achieving a clinical pregnancy using daily GnRHa injections, the corresponding chance using GnRHa depot would be between 25% and 35%.

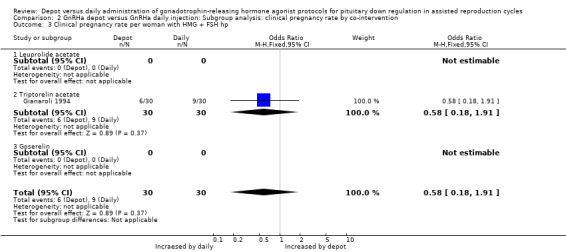

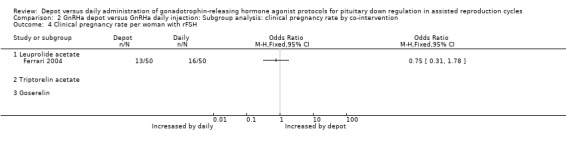

There were no evident differences for this outcome when it was analysed according to type of agonist, use of co‐interventions or quality of allocation concealment (Analysis 2.1; Analysis 2.2; Analysis 2.3; Analysis 2.4; Analysis 3.2).

2.1. Analysis.

Comparison 2 GnRHa depot versus GnRHa daily injection: Subgroup analysis: clinical pregnancy rate by co‐intervention, Outcome 1 Clinical pregnancy rate per woman with FSH hp.

2.2. Analysis.

Comparison 2 GnRHa depot versus GnRHa daily injection: Subgroup analysis: clinical pregnancy rate by co‐intervention, Outcome 2 Clinical pregnancy rate per woman with HMG.

2.3. Analysis.

Comparison 2 GnRHa depot versus GnRHa daily injection: Subgroup analysis: clinical pregnancy rate by co‐intervention, Outcome 3 Clinical pregnancy rate per woman with HMG + FSH hp.

2.4. Analysis.

Comparison 2 GnRHa depot versus GnRHa daily injection: Subgroup analysis: clinical pregnancy rate by co‐intervention, Outcome 4 Clinical pregnancy rate per woman with rFSH.

3.2. Analysis.

Comparison 3 GnRHa depot versus GnRHa daily injection: Sensitivity analysis: live birth/ongoing pregnancy rate and clinical pregnancy rate in studies with adequate allocation concealment, Outcome 2 Clinical pregnancy rate per woman.

1.3 Ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome (OHSS) incidence

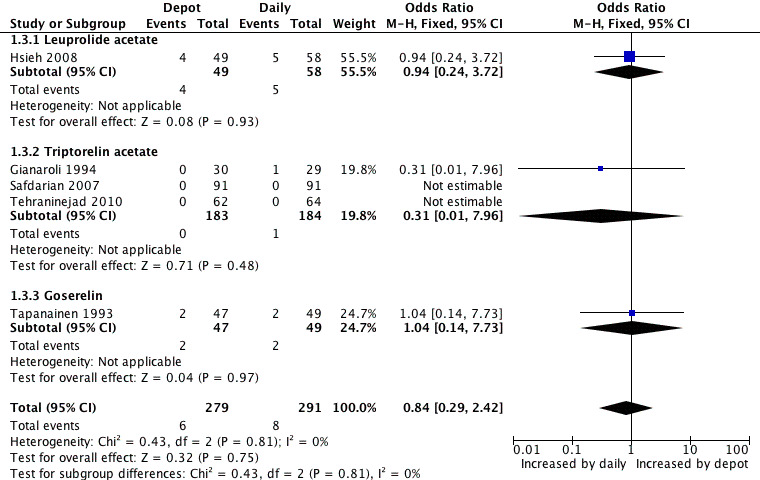

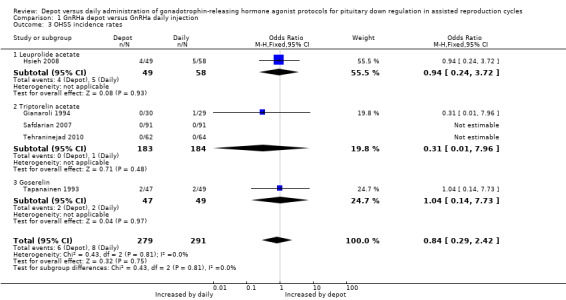

Only five studies were included in this analysis (Gianaroli 1994; Hsieh 2008; Safdarian 2007; Tapanainen 1993; Tehraninejad 2010). The incidence of severe ovarian hyperstimulation syndrome was not significantly different among women treated with depot GnRHa (6/279, 2.1%) compared to women who received daily GnRHa (8/291, 2.7%) (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.29 to 2.42, Figure 6; Analysis 1.3). Tehraninejad 2010 reported no OHSS in the two treatment arms of his study. There was no statistical heterogeneity in this comparison (test for heterogeneity: Chi² = 0.43, df = 2, P = 0.81; I² = 0%). This means that for a woman with a 3% risk of severe OHSS using daily GnRHa injections, the corresponding risk using GnRHa depot would be between 1% and 6%.

6.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 GnRHa depot versus GnRHa daily injection, outcome: 1.3 OHSS incidence rates.

1.3. Analysis.

Comparison 1 GnRHa depot versus GnRHa daily injection, Outcome 3 OHSS incidence rates.

No significant differences were detected when this outcome was analysed according to type of agonist or use of co‐intervention. Findings did not differ in the only two studies that reported adequate allocation concealment (Safdarian 2007; Tapanainen 1993).

Secondary outcomes

1.4 Number of oocytes retrieved

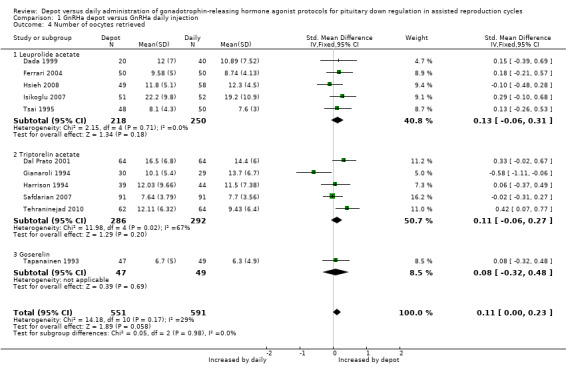

Eleven studies were included (Dada 1999; Dal Prato 2001; Ferrari 2004; Gianaroli 1994; Harrison 1994; Hsieh 2008; Isikoglu 2007; Safdarian 2007; Tapanainen 1993; Tehraninejad 2010; Tsai 1995). The mean number of oocytes retrieved was not significantly different in the 551 women using depot GnRHa compared to the 591 women using daily GnRHa (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.11, 95% CI ‐0.00 to 0.23, Analysis 1.4). There was no statistical heterogeneity in this comparison (test for heterogeneity: Chi² = 14.18, df = 10, P = 0.17; I² = 29%).

1.4. Analysis.

Comparison 1 GnRHa depot versus GnRHa daily injection, Outcome 4 Number of oocytes retrieved.

The findings did not change when we performed analyses according to type of agonist.

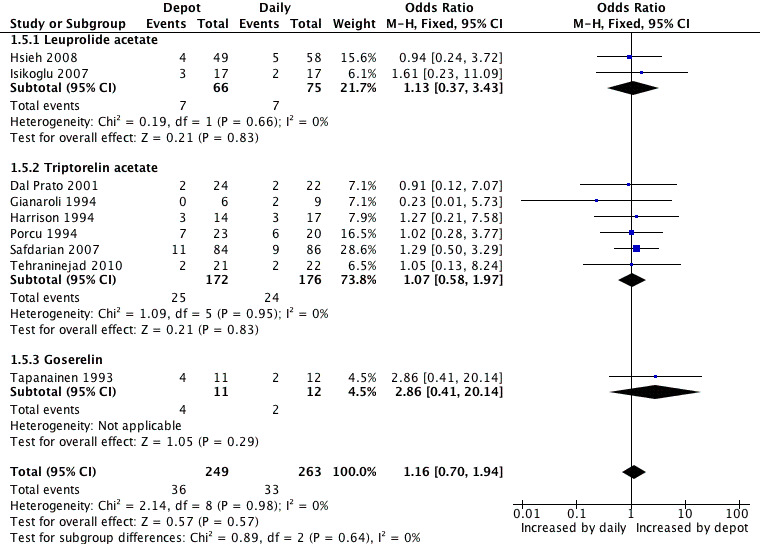

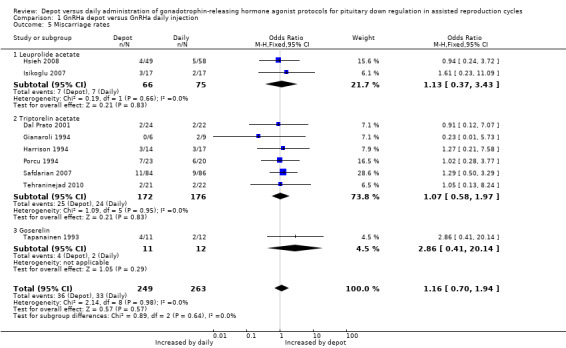

1.5 Miscarriage rates

Eight studies were included (Dal Prato 2001; Gianaroli 1994; Harrison 1994; Hsieh 2008; Isikoglu 2007; Porcu 1994; Safdarian 2007; Tapanainen 1993; Tehraninejad 2010). The miscarriage rate was 14.4% (36/249) (14.4%) in pregnancies conceived by women treated with depot GnRHa and 12.5% (3/263) among those that used daily GnRHa; this difference was not statistically significant (OR 1.16, 95% CI 0.70 to 1.94, Figure 7; Analysis 1.5). There was no statistical heterogeneity in this comparison (test for heterogeneity: Chi² = 2.14, df = 8, P = 0.98; I² = 0%).

7.

Forest plot of comparison: 1 GnRHa depot versus GnRHa daily injection, outcome: 1.5 Miscarriage rates.

1.5. Analysis.

Comparison 1 GnRHa depot versus GnRHa daily injection, Outcome 5 Miscarriage rates.

Analyses according to type of agonist resulted in the same findings.

1.6 Multiple pregnancy rates

Only four studies reported multiple pregnancy rates (Gianaroli 1994; Harrison 1994; Porcu 1994; Tehraninejad 2010). This rate was 16/64 (25.0%) in the group treated with depot GnRHa and 16/68 (23.5%) in the group given daily GnRHa (OR 1.10, 95% CI 0.49 to 2.46), a non‐significant difference. There was no statistical heterogeneity in this comparison (test for heterogeneity: Chi² = 1.52, df = 3, P = 0.68; I² = 0%).

There were no differences for this outcome when analysed according to type of agonist.

Cost

No studies reported this outcome.

Patient convenience

No studies reported this outcome.

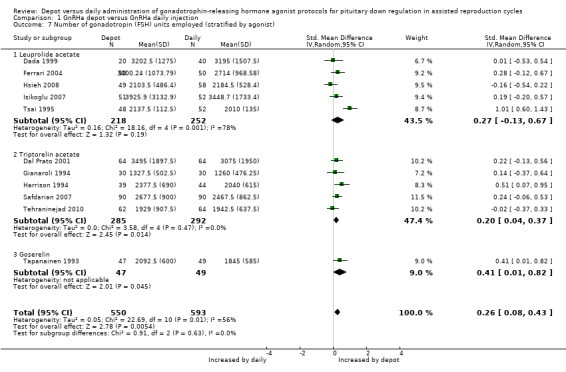

1.7 Number of gonadotropin (FSH) units employed (stratified by agonist)

Eleven studies were included (Dada 1999; Dal Prato 2001; Ferrari 2004; Gianaroli 1994; Harrison 1994; Hsieh 2008; Isikoglu 2007; Safdarian 2007; Tapanainen 1993; Tehraninejad 2010; Tsai 1995). Overall, significantly more gonadotrophin units were needed for ovarian stimulation in the 550 cycles using depot GnRHa compared with the 593 cycles using daily GnRHa (SMD 0.26, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.43, Analysis 1.7).

1.7. Analysis.

Comparison 1 GnRHa depot versus GnRHa daily injection, Outcome 7 Number of gonadotropin (FSH) units employed (stratified by agonist).

There was significant heterogeneity in this comparison (test for heterogeneity: Chi² = 22.69, df = 10, P = 0.01; I² = 56%). The probable cause for this heterogeneity is the study by Tsai 1995 which included 43‐year old women (poor responders) which significantly increased the standard deviation of the sample. When we excluded this study, the heterogeneity disappeared (test for heterogeneity: Chi² = 8.62, df = 9, P = 0.47; I² = 0%).

We identified no differences between the studies using different types of agonist.

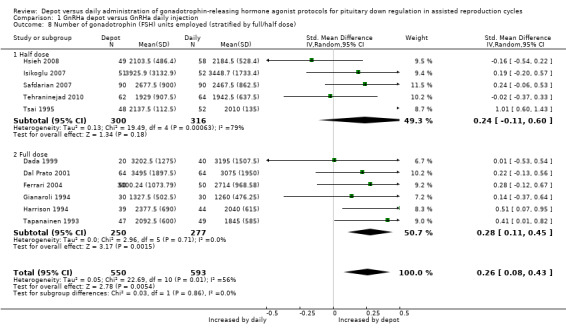

1.8 Number of gonadotropin (FSH) units employed (stratified by full/half dose)

1.8.1 Five studies reporting the use of half doses of depot GnRHa were included (Hsieh 2008; Isikoglu 2007; Safdarian 2007; Tehraninejad 2010; Tsai 1995). The number of gonadotropin units employed did not differ significantly in the 300 cycles using half‐dose depot compared with the 316 cycles using daily GnRHa (SMD 0.24, 95% CI ‐0.11 to 0.06, Analysis 1.8). There was statistical heterogeneity in this comparison (test for heterogeneity: Tau² = 0.13; Chi² = 19.49, df = 4, P = 0.0006; I² = 79%). Potential reasons for this heterogeneity were previously described (1.7 Number of gonadotropin (FSH) units employed).

1.8. Analysis.

Comparison 1 GnRHa depot versus GnRHa daily injection, Outcome 8 Number of gonadotrophin (FSH) units employed (stratified by full/half dose).

1.8.2 Six studies reporting the use of full doses of depot GnRHa were included (Dada 1999; Dal Prato 2001; Ferrari 2004; Gianaroli 1994; Harrison 1994; Tapanainen 1993). Significantly more gonadotrophin units were needed for ovarian stimulation in the 250 cycles using standard depot GnRHa dose compared with the 277 cycles using daily GnRHa (SMD 0.28, 95% CI 0.11 to 0.45, Analysis 1.8).

1.9 Number of days of gonadotrophin treatment (stratified by agonist)

Ten studies were included (Dada 1999; Dal Prato 2001; Ferrari 2004; Gianaroli 1994; Harrison 1994; Isikoglu 2007; Safdarian 2007; Tapanainen 1993; Tehraninejad 2010; Tsai 1995). In the 10 studies that reported days of gonadotrophin treatment, the 501 cycles using depot GnRHa required a significantly longer duration of ovarian stimulation than the 532 cycles using daily GnRHa (mean difference (MD) 0.65, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.84, Analysis 1.9). There was no statistical heterogeneity in this comparison (test for heterogeneity: Chi² = 12.96, df = 9, P = 0.16; I² = 31%).

1.9. Analysis.

Comparison 1 GnRHa depot versus GnRHa daily injection, Outcome 9 Number of days of gonadotrophin treatment (stratified by agonist).

Significantly more days of gonadotropin treatment were needed for women receiving depot GnRHa, when analysed according to type of agonist used (Analysis 1.9).

1.10 Number of days of gonadotrophin treatment (stratified by full/half dose)

1.10.1 Four studies reporting the use of half doses of depot GnRHa were included (Isikoglu 2007; Safdarian 2007; Tehraninejad 2010; Tsai 1995). In the four studies that reported days of gonadotrophin treatment, the 251 cycles using half‐dose depot GnRHa required a significantly longer duration of ovarian stimulation than the 256 cycles using daily GnRHa (MD 0.64, 95% CI 0.36 to 0.92, Analysis 1.10). There was unexplained heterogeneity in this comparison (test for heterogeneity: Chi² = 6.30, df = 3, P = 0.10; I² = 52%).

1.10. Analysis.

Comparison 1 GnRHa depot versus GnRHa daily injection, Outcome 10 Number of days of gonadotrophin treatment (stratified by full/half dose).

1.10.2 Six studies reporting the use of full doses of depot GnRha were included (Dada 1999; Dal Prato 2001; Ferrari 2004; Gianaroli 1994; Harrison 1994; Tapanainen 1993). In the four studies which reported days of gonadotrophin treatment, the 250 cycles using full‐dose depot GnRHa required a significantly longer duration of ovarian stimulation than the 276 cycles using daily GnRHa (MD 0.66, 95% CI 0.41 to 0.92, Analysis 1.10). There was statistical heterogeneity in this comparison (test for heterogeneity: Chi² = 6.64, df = 5, P = 0.25; I² = 25%).

Discussion

Summary of main results

Sixteen studies, with a total of 1811 women, were included and analysed. We did not detect significant differences between depot gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone agonist (GnRHa) or daily GnRHa on long protocols for any of our primary outcomes: live birth/ongoing pregnancy rate per woman (odds ratio (OR) 0.95, 95% confidence interval (CI) 0.70 to 1.31), clinical pregnancy rate per woman (OR 0.96, 95% CI 0.75 to 1.23) and incidence of OHSS (OR 0.84, 95% CI 0.29 to 2.42), as well as number of oocytes retrieved, miscarriage rate and multiple pregnancy rate. However, the use of depot GnRHa for pituitary down regulation in in vitro fertilisation (IVF) cycles increased the number of gonadotropin (FSH) units employed (standardised mean difference (SMD) 0.26, 95% CI 0.08 to 0.43) and the duration of ovarian stimulation (mean difference (MD) 0.65, 95% CI 0.46 to 0.84), when compared with daily GnRHa injections.

As expected and as previously suggested by some authors, GnRHa causes extra‐pituitary side effects, including direct inhibition of ovarian steroidogenesis (Dor 2000; Gonen 1991; Lipitz 1989). In vitro studies have also shown that GnRHa can affect the differentiation of granulosa cells (Gaetje 1994; Gerrero 1993; Parinaud 1988; Uemura 1994), as well as GnRH receptor messenger ribonucleic acids in these cells (Minaretzis 1995; Peng 1994).

In subgroup analyses, we grouped studies according to the dose of depot GnRHa. A half‐dose injection, as compared to a full dose, seems to be equally effective in a pituitary down regulation (Balash 1992; Geber 2002; Isikoglu 2007). It is still unknown whether the use of half doses would also reduce the effects on ovarian tissue. Assuming that this would occur, the use of half doses would have the same effects as daily doses and we would therefore need a smaller dose of gonadotrophin for ovulation induction in IVF cycles. When we analysed a subgroup with full dose and half dose, we found no statistical difference in the number of units of gonadotrophins in the study group with half dose versus daily dose (SMD 0.24, 95% CI ‐0.11 to 0.06).

If one considers the cost of one IVF treatment cycle, when the long protocol is used for pituitary gland down regulation, the costs will certainly be higher for the women using depot GnRHa. Thus, if the costs of depot and daily GnRHa are similar and the outcomes are comparable, as indicated in this systematic review, anything that could be done to reduce the number of gonadotrophin ampoules used for each cycle should lead to a better cost‐benefit relation, in the long run (Devreker 1996; Wong 2001).

Overall completeness and applicability of evidence

Only four studies reported live birth rates and only seven reported ongoing pregnancy. Ideally, the take‐home baby rate per woman should be reported by all trials or, failing this, the ongoing/delivered pregnancy rate per woman randomised. Many studies only reported clinical pregnancy rates, which are not a long‐term outcome of interest to consumers.

No studies reported data on cost or patient convenience.

This review did not include any unpublished studies. Several pharmaceutical companies replied to our requests (AstraZeneca, Searly, Ferring and Pharmacia), but the studies sent by them had already been included in this review or excluded from it.

Of the 16 articles included, only one reported data on side effects (Tapanainen 1993). This study asked women to fill in a weekly subjective estimation scale for different side effects (ranging from 1 = absent to 5 = severe). The first questionnaire was answered before onset of treatment and the last form was filled in three weeks after oocyte retrieval. The following side effects were assessed: tiredness, depression, irritability, headache, nausea, swelling and abdominal pain. The author concluded that women in both groups had similar irritability, nausea and abdominal swelling. On the other hand, they also reported that during the first two to three weeks of treatment, women taking buserelin reported significantly more tiredness, depression, headache and abdominal pain than those given goserelin.

Two studies (Safdarian 2007; Tehraninejad 2010) only included participants aged under 36 and three studies (Dada 1999; Dal Prato 2001; Gianaroli 1994) only included those under 38 years of age. Most studies did not include women over 38 years of age, as older women have lesser ovarian reserve and consequently lower ovarian response. Therefore since it has been suggested that GnRHa interferes directly in steroid genesis, it would be important to investigate whether women over 38 years of age would benefit from the use of daily GnRHa (Dal Prato 2001; Geber 2002; Wong 2001).

Quality of the evidence

See Table 1; Table 2. Table were developed in GRADE PRO 2011.

We rated the quality of the evidence as low according to the GRADE PRO 2011 software we used, except for the primary outcome 'Clinical pregnancy rate per woman' that we classified as moderate. The study by Tsai 1995 is the probable reason for the large standard deviation between studies for the secondary outcome 'Number of gonadotropin (FSH) units employed', which led us to grade the evidence for this outcome as being of low quality. Tsai 1995 included 43‐year old women, who are poor responders and therefore need more FSH units for ovulation induction and thus significantly increase the standard deviation of that study (Table 1).

In the subgroup analysis of different doses of depot GnRHa (full dose and half dose) the quality of evidence was low for most of the outcomes. For the outcome 'Number of gonadotrophin (FSH) units employed ‐ half dose' the quality evidence was very low because of unexplained heterogeneity among the studies (Table 2).

Overall study quality was unclear due to poor reporting of methods, and only five studies clearly reported an adequate method of allocation concealment (Dada 1999; Dal Prato 2001; Harrison 1994; Safdarian 2007; Tapanainen 1993). A sensitivity analysis for the outcome 'Clinical pregnancy' including only these five studies reached the same conclusion, indicating no differences in favour of any of the interventions. For the 'Live birth/ongoing pregnancy' outcome only four studies reached the same conclusion of no differences in favour of any of the interventions (Dal Prato 2001; Harrison 1994; Safdarian 2007; Tapanainen 1993).

Potential biases in the review process

A limitation of this review is the lack of full data from all studies, despite our attempts to obtain missing information from primary study authors. The combination of live birth data with data on ongoing pregnancy could potentially influence the results, although findings were similar for these two outcomes. This is a reasonable approach until more studies report live birth as an outcome. The risk of publication bias is low (Figure 8). No other likely sources of biases in the review process were identified.

8.

Funnel plot of comparison: 1 GnRHa depot versus GnRHa daily injection, outcome: 1.2 Clinical pregnancy rate per woman.

Agreements and disagreements with other studies or reviews

We were careful in grouping the results according to the type of depot GnRHa used in the studies analysed. This approach is justified because in a previous study, in which cultured human luteinising granulosa cells were used, some but not all of the GnRHa tested affected estradiol secretion and cell surface morphology (Bussenot 1993).

No other review on this subject was found.

Authors' conclusions

Implications for practice.

There is insufficient evidence that the use of depot gonadotrophin‐releasing hormone agonist (GnRHa) is better or worse than daily GnRHa in the long protocol for pituitary down regulation for in vitro fertilisation (IVF) cycles. Therefore, clinicians should use GnRHa administration according to their preference.

The use of depot GnRHa for pituitary down regulation in IVF cycles requires more gonadotrophin units for ovarian stimulation than daily GnRHa injections, and is associated with a significantly longer duration of ovarian stimulation than daily GnRHa. However, these findings should be interpreted with caution because of the low quality of the evidence for most outcomes reported in this review.

Implications for research.

New randomised controlled trials of good quality are necessary to evaluate the effectiveness of depot GnRHa for pituitary down regulation in IVF cycles compared with daily GnRHa. The primary outcome should be live birth; patient convenience and costs should also be assessed. Studies are also needed to determine whether differences in the number of gonadotrophin ampoules required significantly influence cost‐effectiveness.

What's new

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 3 July 2012 | New citation required but conclusions have not changed | We carried out a new search on 3 July 2012. Seven new trials were added (Ferrari 2004; Hsieh 2008; Isikoglu 2007; Librati 1996; Porcu 1994; Safdarian 2007; Tehraninejad 2010) totaling 1811 participants, but the conclusions did not change. |

| 3 July 2012 | New search has been performed | Two new co‐authors were added (Leopoldo Tso and Cristiane R Macedo). Seven new trials were added. There were no changes to the conclusions. |

History

Protocol first published: Issue 4, 2000 Review first published: Issue 3, 2002

| Date | Event | Description |

|---|---|---|

| 10 November 2008 | Amended | Converted to new review format. |

| 17 November 2004 | New citation required and conclusions have changed | Substantive amendment. One new quasi‐randomised trial was excluded from the review. |

Acknowledgements

The review authors wish to express their gratitude to Prof. Dr. Vilmon de Freitas (in memoriam) and to Prof. Dr. Luiz Eduardo Vieira Diniz for their constant encouragement and support throughout the development of this systematic review, and to Rubens Albuquerque for assistance with the English version of this study.

Appendices

Appendix 1. Search strategy 2012

Database: Cochrane Menstrual Disorders and Subfertility Group Trials Register

Search strategy: ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐

Keywords CONTAINS "GnRh" or "buserelin" or "Goserelin" or "leuprolide" or "leuprolin" or"nafarelin" or "triptorelin" or "Gonadotrophin releasing hormone" or "GnRH a" or "GnRH agonist" or "GnRH agonist short protocol" or "GnRH agonists" or "GnRH analog" or "GnRH analogue" or "GnRH analogues" or "GnRHa" or "GnRHa‐gonadotropin" or "Gonadorelin" or "Gonadotrophin releasing agonist" or "Gonadotrophin releasing hormones" or "gonadotrophins" or "gonadotrophin" or "gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist" or "deslorelin" or Title CONTAINS"GnRH agonists" or "GnRH analog" or "GnRH analogue" or "GnRH analogues" or "GnRHa" or "GnRHa‐gonadotropin" or "Gonadorelin" or "Gonadotrophin releasing agonist" or "Gonadotrophin releasing hormones" or "gonadotrophins" or "gonadotrophin" or "gonadotropin releasing hormone agonist" or "deslorelin"

AND

Keywords CONTAINS "IVF" or "ICSI" or "in‐vitro fertilisation " or "in vitro fertilization" or "in‐vitro fertilisation procedure" or "in‐vitro fertilisation techniques" or "intracytoplasmic morphologically selected sperm injection" or "intracytoplasmic sperm injection" or "intracytoplasmic sperm injection cycle" or "intracytoplasmic sperm injection techniques" or Title CONTAINS "IVF" or "ICSI" or "in‐vitro fertilisation " or "in vitro fertilization" or "in‐vitro fertilisation procedure" or "in‐vitro fertilisation techniques" or "intracytoplasmic morphologically selected sperm injection" or "intracytoplasmic sperm injection" or "intracytoplasmic sperm injection cycle" or "intracytoplasmic sperm injection techniques"

Database: Cochrane Central Register of Controlled Trials (CENTRAL) (The Cochrane Library 2012, Issue 7)

Search strategy: ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐ 1 exp gonadotropin‐releasing hormone/ or exp buserelin/ or exp goserelin/ or exp leuprolide/ or exp nafarelin/ or exp triptorelin/ (1625) 2 gonadotropin‐releasing hormone$.tw. (645) 3 buserelin.tw. (263) 4 goserelin.tw. (314) 5 leuprolide.tw. (367) 6 nafarelin.tw. (101) 7 triptorelin.tw. (147) 8 (Lupron or Eligard).tw. (30) 9 (suprefact or Suprecor).tw. (8) 10 synarel.tw. (3) 11 supprelin.tw. (0) 12 Zoladex.tw. (211) 13 GnRHa$.tw. (179) 14 (GnRH a or GnRH agonist$).tw. (1143) 15 deslorelin.tw. (8) 16 (Suprelorin or Ovuplant).tw. (0) 17 histrelin.tw. (0) 18 gonadotrophin releasing hormone$.tw. (272) 19 desensitization.tw. (784) 20 desensitisation.tw. (39) 21 exp Down‐Regulation/ (235) 22 Downregulation.tw. (184) 23 or/1‐22 (3751) 24 exp delayed‐action preparations/ or exp drug implants/ (4544) 25 delayed‐action.tw. (63) 26 depot.tw. (986) 27 implant.tw. (2038) 28 long term.tw. (28030) 29 depo.tw. (80) 30 (single adj2 dos$).tw. (17313) 31 (single adj2 administrat$).tw. (2190) 32 (single adj2 inject$).tw. (1183) 33 long act$.tw. (2718) 34 or/24‐33 (54403) 35 23 and 34 (769) 36 exp reproductive techniques, assisted/ or exp embryo transfer/ or exp fertilization in vitro/ or exp sperm injections, intracytoplasmic/ (1920) 37 assisted reproductive technique$.tw. (30) 38 (in vitro fertilization or in vitro fertilisation).tw. (1203) 39 (IVF or ICSI).tw. (1927) 40 or/36‐39 (3095) 41 35 and 40 (139) 42 limit 41 to yr="2004 ‐Current" (26) 43 from 42 keep 1‐26 (26)

Database: MEDLINE via OVID (1980 to 2012 Week 40)

Search strategy: ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐

1 exp gonadotropin‐releasing hormone/ or exp buserelin/ or exp goserelin/ or exp leuprolide/ or exp nafarelin/ or exp triptorelin/ (27540) 2 gonadotropin‐releasing hormone$.tw. (10001) 3 buserelin.tw. (1196) 4 goserelin.tw. (689) 5 leuprolide.tw. (1400) 6 nafarelin.tw. (241) 7 triptorelin.tw. (480) 8 (Lupron or Eligard).tw. (154) 9 (suprefact or Suprecor).tw. (22) 10 synarel.tw. (11) 11 supprelin.tw. (2) 12 Zoladex.tw. (365) 13 GnRHa$.tw. (1006) 14 (GnRH a or GnRH agonist$).tw. (3622) 15 deslorelin.tw. (160) 16 (Suprelorin or Ovuplant).tw. (15) 17 histrelin.tw. (37) 18 gonadotrophin releasing hormone$.tw. (2366) 19 desensitization.tw. (17847) 20 desensitisation.tw. (848) 21 exp Down‐Regulation/ (50235) 22 Downregulation.tw. (27787) 23 or/1‐22 (118161) 24 exp delayed‐action preparations/ or exp drug implants/ (37790) 25 delayed‐action.tw. (620) 26 depot.tw. (7790) 27 implant.tw. (62345) 28 long term.tw. (449541) 29 depo.tw. (1048) 30 (single adj2 dos$).tw. (65424) 31 (single adj2 administrat$).tw. (10074) 32 (single adj2 inject$).tw. (22983) 33 long act$.tw. (14821) 34 or/24‐33 (639901) 35 23 and 34 (7701) 36 exp reproductive techniques, assisted/ or exp embryo transfer/ or exp fertilization in vitro/ or exp sperm injections, intracytoplasmic/ (49267) 37 assisted reproductive technique$.tw. (863) 38 (in vitro fertilization or in vitro fertilisation).tw. (14941) 39 (IVF or ICSI).tw. (16484) 40 or/36‐39 (53981) 41 35 and 40 (484) 42 randomized controlled trial.pt. (388995) 43 controlled clinical trial.pt. (85371) 44 randomized.ab. (241793) 45 placebo.tw. (139188) 46 clinical trials as topic.sh. (163008) 47 randomly.ab. (173502) 48 trial.ti. (104412) 49 (crossover or cross‐over or cross over).tw. (50919) 50 or/42‐49 (798926) 51 (animals not (humans and animals)).sh. (3701883) 52 50 not 51 (734601) 53 41 and 52 (142) 54 (2004$ or 2005$ or 2006$ or 2007$ or 2008$ or 2009$ or 2010$ or 2011$ 2012$).ed. (6532265) 55 53 and 54 (54) 56 from 55 keep 1‐54 (54)

Database: EMBASE (1980 to 2012 Week 26)

Search strategy: ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐

1 exp gonadorelin agonist/ (9276) 2 gonadorelin.tw. (234) 3 exp buserelin/ or exp buserelin acetate/ (4497) 4 exp goserelin/ (5224) 5 exp leuprorelin/ (7675) 6 exp nafarelin acetate/ or exp nafarelin/ (1274) 7 exp triptorelin/ (3636) 8 gonadotropin‐releasing hormone agonist$.tw. (1696) 9 (buserelin or goserelin).tw. (2354) 10 (leuprolide or nafarelin).tw. (2106) 11 triptorelin.tw. (670) 12 (Lupron or Eligard).tw. (1571) 13 (suprefact or Suprecor).tw. (898) 14 synarel.tw. (299) 15 supprelin.tw. (43) 16 Zoladex.tw. (1862) 17 GnRHa$.tw. (1296) 18 (GnRH a or GnRH agonist$).tw. (4713) 19 deslorelin.tw. (175) 20 (Suprelorin or Ovuplant).tw. (23) 21 histrelin.tw. (67) 22 gonadotrophin releasing hormone agonist$.tw. (478) 23 desensitization.tw. (20403) 24 desensitisation.tw. (1205) 25 exp down regulation/ (85660) 26 Down‐Regulation.tw. (50374) 27 or/1‐26 (153524) 28 exp delayed release formulation/ (7727) 29 depot.tw. (10153) 30 delayed‐action.tw. (577) 31 implant.tw. (72402) 32 long term.tw. (565198) 33 depo.tw. (2598) 34 (single adj2 dos$).tw. (76816) 35 (single adj2 administrat$).tw. (12013) 36 (single adj2 inject$).tw. (24348) 37 long act$.tw. (19119) 38 or/28‐37 (765027) 39 exp infertility therapy/ or exp embryo transfer/ or exp fertilization in vitro/ or exp intracytoplasmic sperm injection/ (68652) 40 assisted reproductive technique$.tw. (1278) 41 (in vitro fertilization or in vitro fertilisation).tw. (18377) 42 (IVF or ICSI).tw. (23888) 43 or/39‐42 (73603) 44 27 and 38 and 43 (606) 45 Clinical Trial/ (867728) 46 Randomized Controlled Trial/ (324293) 47 exp randomization/ (58661) 48 Single Blind Procedure/ (16047) 49 Double Blind Procedure/ (109462) 50 Crossover Procedure/ (34246) 51 Placebo/ (200426) 52 Randomi?ed controlled trial$.tw. (76061) 53 Rct.tw. (9482) 54 random allocation.tw. (1151) 55 randomly allocated.tw. (17271) 56 allocated randomly.tw. (1811) 57 (allocated adj2 random).tw. (708) 58 Single blind$.tw. (12263) 59 Double blind$.tw. (128449) 60 ((treble or triple) adj blind$).tw. (270) 61 placebo$.tw. (175748) 62 prospective study/ (206989) 63 or/45‐62 (1255203) 64 case study/ (16016) 65 case report.tw. (226142) 66 abstract report/ or letter/ (835489) 67 or/64‐66 (1073067) 68 63 not 67 (1220198) 69 44 and 68 (242) 70 (2004$ or 2005$ or 2006$ or 2007$ or 2008$ or 2009$ or 2011$ or 2012$).em. (1685031) 71 69 and 70

Database: LILACS (1982 to 2012)

Search strategy: ‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐‐