Summary

This paper is the first in a three-part series on preterm birth, which is the leading cause of perinatal morbidity and mortality in developed countries. Infants are born preterm at less than 37 weeks' gestational age after: (1) spontaneous labour with intact membranes, (2) preterm premature rupture of the membranes (PPROM), and (3) labour induction or caesarean delivery for maternal or fetal indications. The frequency of preterm births is about 12–13% in the USA and 5–9% in many other developed countries; however, the rate of preterm birth has increased in many locations, predominantly because of increasing indicated preterm births and preterm delivery of artificially conceived multiple pregnancies. Common reasons for indicated preterm births include pre-eclampsia or eclampsia, and intrauterine growth restriction. Births that follow spontaneous preterm labour and PPROM—together called spontaneous preterm births—are regarded as a syndrome resulting from multiple causes, including infection or inflammation, vascular disease, and uterine overdistension. Risk factors for spontaneous preterm births include a previous preterm birth, black race, periodontal disease, and low maternal body-mass index. A short cervical length and a raised cervical-vaginal fetal fibronectin concentration are the strongest predictors of spontaneous preterm birth.

This is the first in a Series of three papers about preterm birth

Introduction

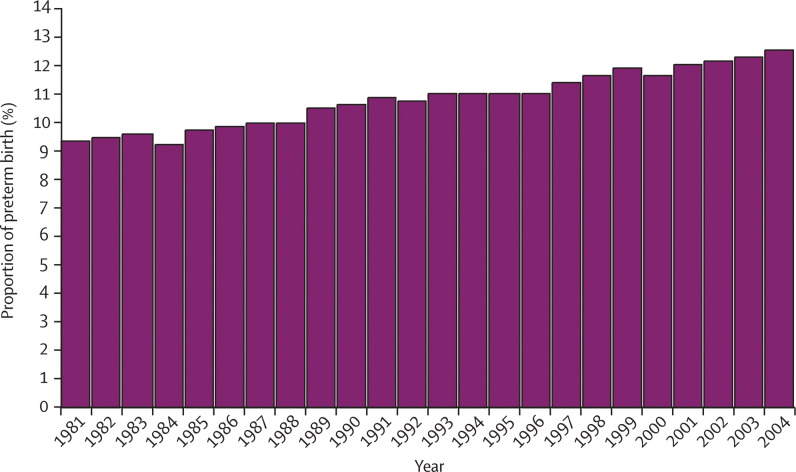

Preterm deliveries are those that occur at less than 37 weeks' gestational age; however, the low-gestational age cutoff, or that used to distinguish preterm birth from spontaneous abortion, varies by location. In the USA, the preterm delivery rate is 12–13%; in Europe and other developed countries, reported rates are generally 5–9%.1, 2 The preterm birth rate has risen in most industrialised countries, with the USA rate increasing from 9·5% in 1981 to 12·7% in 2005 (figure 1 ),2 despite advancing knowledge of risk factors and mechanisms related to preterm labour, and the introduction of many public health and medical interventions designed to reduce preterm birth.3 Potential methods used to reduce preterm birth will be discussed in the second paper in this series.4

Figure 1.

Percentage of all births classified as preterm in the USA, 1981–2004

Source: Martin JA, Kochanek KD, Strobino DM, Guyer B, MacDorman MF. Annual summary of vital statistics—2003. Pediatrics 2005; 115: 619–34.

Preterm births account for 75% of perinatal mortality and more than half the long-term morbidity.5 Although most preterm babies survive, they are at increased risk of neurodevelopmental impairments and respiratory and gastrointestinal complications. The outcome of preterm births will be discussed in detail in the third paper in this series.6 Here, we explore the epidemiology, causes, and mechanisms leading to preterm births.

Epidemiology

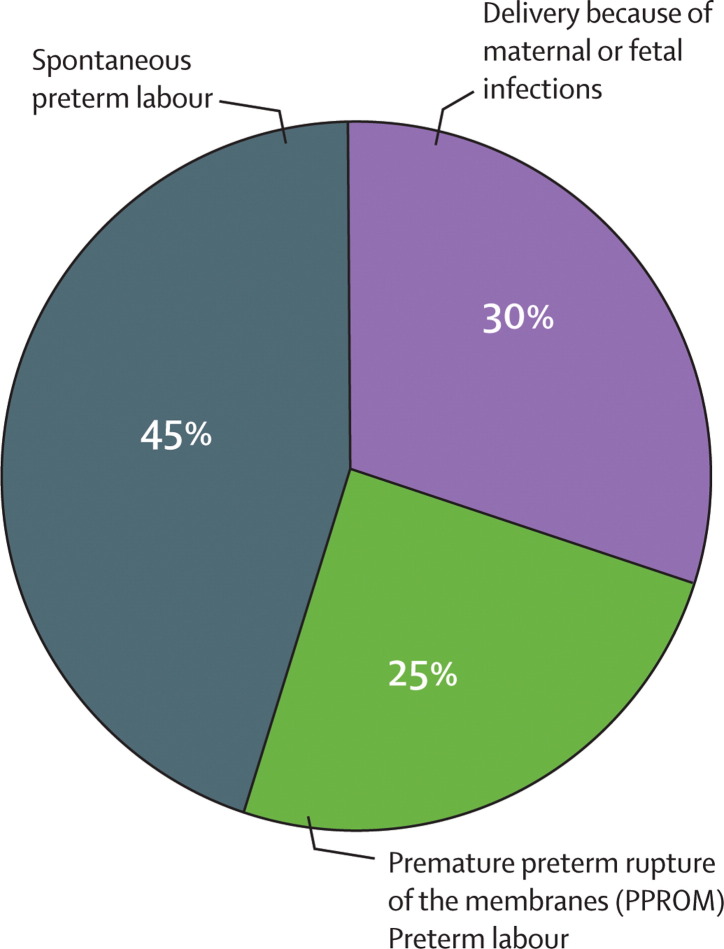

The obstetric precursors leading to preterm birth are: (1) delivery for maternal or fetal indications, in which labour is either induced or the infant is delivered by prelabour caesarean section; (2) spontaneous preterm labour with intact membranes; and (3) preterm premature rupture of the membranes (PPROM), irrespective of whether delivery is vaginal or by caesarean section (figure 2 ).7 About 30–35% of preterm births are indicated, 40–45% follow spontaneous preterm labour, and 25–30% follow PPROM; births that follow spontaneous labour and PPROM are together designated spontaneous preterm births. The contribution of the causes of preterm births to all preterm births differs by ethnic group. Spontaneous preterm birth is most commonly caused by preterm labour in white women, but by PPROM in black women.8 Preterm births can also be subdivided according to gestational age: about 5% of preterm births occur at less than 28 weeks' (extreme prematurity), about 15% at 28–31 weeks' (severe prematurity), about 20% at 32–33 weeks' (moderate prematurity), and 60–70% at 34–36 weeks' (near term).

Figure 2.

Obstetric precursors of preterm birth

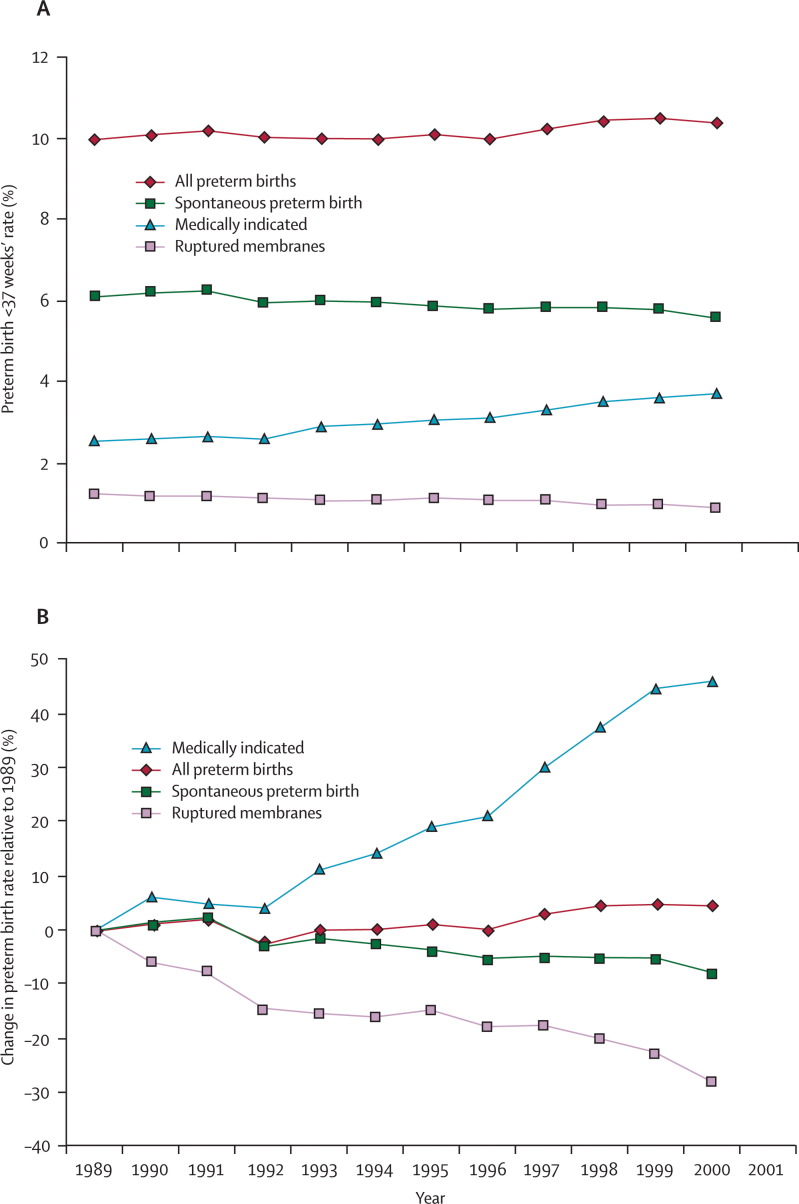

Much of the increase in the singleton preterm birth rate is explained by rising numbers of indicated preterm births (figure 3 ).9 A high number of preterm multiple gestations associated with assisted reproductive technologies is also an important contributor to the overall increase in preterm births. Singleton pregnancies after in-vitro fertilisation are also at increased risk of preterm birth.10 In the USA, increasing indicated preterm births mask a small, but important, reduction in spontaneous preterm births, especially in black women.11

Figure 3.

Temporal changes in singleton preterm births overall and temporal changes resulting from ruptured membranes, medically indicated preterm labour, and spontaneous preterm labour in USA, 1989–2000

A) Rates in each group by year. B) The percentage change in rates relative to 1989. Figure adapted from reference 9.

PPROM is defined as spontaneous rupture of the membranes at less than 37 weeks' gestation at least 1 h before the onset of contractions. The cause of membrane rupture in most cases is unknown, but asymptomatic intrauterine infection is a frequent precursor. Risk factors for PPROM are generally similar to those for preterm spontaneous labour with intact membranes, although infections and tobacco exposure play important parts.12 Most women with PPROM begin labour spontaneously within several days, but a small proportion of women remains undelivered for weeks or months. Since the membranes generally form a barrier to ascending infection, a common complication of PPROM is development of intrauterine infection and preterm labour.13

Preterm labour is usually defined as regular contractions accompanied by cervical change at less than 37 weeks' gestation. Pathogenesis of preterm labour is not well understood, but preterm labour might represent early idiopathic activation of the normal labour process or the results of pathological insults. A role for the fetus in determining the timing of the onset of labour has been proposed on the basis of studies in sheep.14 Ablation of the fetal hypophysis or adrenal glands, or both, prevents the initiation of parturition; thus fetal cortisol is central to labour initiation in sheep. The same mechanism might be implicated in parturition in women, as suggested by reports of protracted pregnancies with an anencephalic fetus.15 Theories proposed to explain the initiation of term labour are: (1) progesterone withdrawal, (2) oxytocin initiation, and (3) decidual activation. The progesterone withdrawal theory stems from studies in sheep.14, 16 As parturition nears, the fetal-adrenal axis becomes more sensitive to adrenocorticotropic hormone, increasing the secretion of cortisol. Fetal cortisol stimulates placental 17α-hydroxylase activity, which decreases progesterone secretion and increases oestrogen production. The reversal in the oestrogen/progesterone ratio results in increased prostaglandin formation, initiating a cascade of events that culminates in labour. In human beings, serum progesterone concentrations do not fall as labour approaches;16 however, because progesterone antagonists—such as RU486—initiate preterm labour and progestational agents prevent preterm labour, a decrease in local progesterone concentrations or in the number of receptors is a plausible mechanism for initiation of labour.16, 17, 18 Because intravenous oxytocin increases the frequency and intensity of uterine contractions, the assumption is that oxytocin plays a part in labour initiation. However, blood concentrations of oxytocin do not rise before labour and the clearance of oxytocin remains constant; thus oxytocin is unlikely to initiate labour.

An important pathway leading to labour initiation implicates inflammatory decidual activation.19 Although at term, decidual activation seems to be mediated at least in part by the fetal-decidual paracrine system (perhaps through localised decreases in progesterone concentration), in many cases of early preterm labour, decidual activation seems to arise in the context of intrauterine bleeding or an occult intrauterine infection.

Causes of preterm labour

Risk factors

Preterm labour is now thought to be a syndrome initiated by multiple mechanisms, including infection or inflammation, uteroplacental ischaemia or haemorrhage, uterine overdistension, stress, and other immunologically mediated processes.19 A precise mechanism cannot be established in most cases; therefore, factors associated with preterm birth, but not obviously in the causal pathway, have been sought to explain preterm labour. An increasing number of risk factors are thought to interact to cause a transition from uterine quiescence toward preterm labour or PPROM. Since many of the risk factors result in increased systemic inflammation, increasing stimulation of the infection or inflammation pathway might explain some of the increases in preterm births associated with multiple risk factors.20

Defining risk factors for prediction of preterm birth is a reasonable goal for several reasons. First, identification of at-risk women allows initiation of risk-specific treatment.21 Second, the risk factors might define a population useful for studying specific interventions. Finally, identification of risk factors might provide important insights into mechanisms leading to preterm birth. There are many maternal or fetal characteristics that have been associated with preterm birth, including maternal demographic characteristics, nutritional status, pregnancy history, present pregnancy characteristics, psychological characteristics, adverse behaviours, infection, uterine contractions and cervical length, and biological and genetic markers.21

Maternal risk factors

In the USA and in the UK, women classified as black, African-American, and Afro-Caribbean are consistently reported to be at higher risk of preterm delivery: preterm birth rates are in the range of 16–18% in black women compared with 5–9% for white women. Black women are also three to four times more likely to have a very early preterm birth than women from other racial or ethnic groups.22, 23 Part of the discrepancy in preterm birth rates between the USA and other countries might be explained by the high rate of preterm births in the USA black population. Over time, the disparity in preterm birth rates between black and white women has remained largely unchanged and unexplained, and contributes to a cycle of reproductive disadvantage with far-reaching social and medical consequences.24 East Asian and Hispanic women typically have low preterm birth rates. Women from south Asia, including the Indian subcontinent, have high rates of low birthweight caused by decreased fetal growth, but preterm delivery does not seem to be substantially increased. Other maternal demographic characteristics associated with preterm birth include low socioeconomic and educational status, low and high maternal ages, and single marital status.25, 26, 27 The mechanisms by which the maternal demographic characteristics are related to preterm birth are unknown.

Observational studies of the type of work and physical activity related to preterm birth have produced conflicting results.28, 29, 30, 31 Investigation of work-related risk is made difficult by confounding factors; however, even after accounting for population differences, working long hours and undertaking hard physical labour under stressful conditions are probably associated with an increase in preterm birth. The level of physical activity is not consistently related to the rate of preterm birth.

Whether differences in demographic, social, or economic risks, frequent absence of health insurance, and absence of a strong supportive economic and social safety net contribute to the disparity in preterm birth rates between the USA and other developed countries is unknown. Lower gestational age cutoffs for defining preterm birth used in the USA might explain part of the difference in preterm birth rates. What does seem clear, however, is that in many USA immigrant groups, the greater the length of time spent living in the USA, the higher the preterm birth rate; the explanation for this finding is also unknown.

There is a raised risk of preterm birth in pregnancies arising within close temporal proximity to a previous delivery.32 An interpregnancy interval of less than 6 months confers a greater than two-fold increased risk of preterm birth after adjustment for confounding variables.33 Furthermore, women whose first birth was preterm are far more likely to have a short interval than women who had a term first birth, thus compounding the risk. Although the mechanism is not clear, one potential explanation is that the uterus takes time to return to its normal state, including resolution of the inflammatory status associated with the previous pregnancy. Maternal depletion might be another cause because pregnancy consumes maternal stores of essential vitamins, minerals, and aminoacids. A short interval decreases the opportunity to replenish these nutrients.

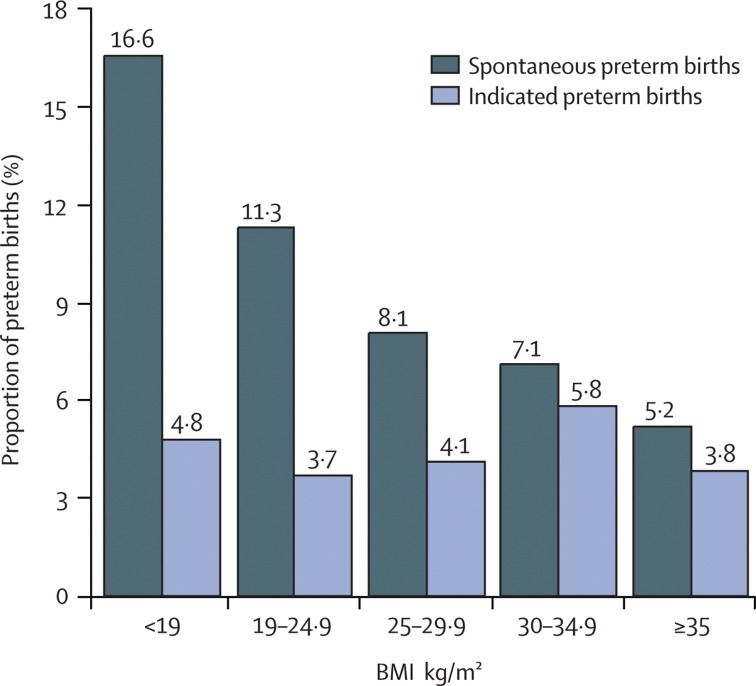

Nutritional status during pregnancy can be described by indicators of body size such as body-mass index (BMI), nutritional intake, and serum assessments for various analytes.34, 35, 36 For example, a low prepregnancy BMI is associated with a high risk of spontaneous preterm birth, whereas obesity can be protective (figure 4 ).35 Women with low serum concentrations of iron, folate, or zinc have more preterm births than those with measurements within the normal range.34, 36 There are many potential mechanisms by which maternal nutritional status might affect preterm birth—eg, spontaneous preterm birth can be caused by maternal thinness associated with decreased blood volume and reduced uterine blood flow.37 Thin women might also consume fewer vitamins and minerals, low concentrations of which are associated with decreased blood flow and increased maternal infections.37, 38 Obese women are more likely to have infants with congenital anomalies, such as neural-tube defects, and these infants are more likely to be delivered preterm.39 Obese women are also more likely to develop pre-eclampsia and diabetes, and have indicated preterm births associated with these disorders.

Figure 4.

Comparison of spontaneous and indicated preterm birth by maternal body-mass index (BMI)

Figure adapted from reference 35.

Pregnancy history

The recurrence risk in women with a previous preterm delivery ranges from 15% to more than 50%, dependent on the number and gestational age of previous deliveries. Mercer and colleagues40 reported that women with previous preterm deliveries had a 2·5–fold increased risk in their next pregnancy. The risk of another preterm birth is inversely related to the gestional age of the previous preterm birth. The mechanism for the recurrence is not always clear, but women with early spontaneous preterm births are far more likely to have subsequent spontaneous preterm births; women with indicated preterm births tend to repeat such births.41, 42 Persistent or recurrent intrauterine infections probably explain many repetitive spontaneous preterm births.41 The underlying disorder causing indicated preterm births, such as diabetes, hypertension, or obesity, frequently persists between pregnancies.

Pregnancy characteristics

Multiple gestations—accounting for only 2–3% of infants—carry a substantial risk of preterm delivery, and result in 15–20% of all preterm births. Nearly 60% of twins are born preterm. About 40% of twins will have spontaneous labour or PPROM before 37 weeks' gestation, with others having an indicated preterm delivery because of pre-eclampsia, or other maternal or fetal disorders. Nearly all higher multiple gestations will result in preterm delivery. Uterine overdistension, resulting in contractions and PPROM, is believed to be the causative mechanism for the rate of increased spontaneous preterm births.19

Vaginal bleeding caused by placental abruption or placenta preavia is associated with a very high risk of preterm delivery, but bleeding in the first and second trimesters that is not associated with either placental abruption or placenta preavia is also associated with subsequent preterm birth.43 Extremes in the volume of amniotic fluid—polyhydramnios or oligohydramnios—are associated with preterm labour and PPROM. Maternal abdominal surgery in the second and third trimesters can stimulate contractions culminating in preterm delivery. Maternal medical disorders, such as thyroid disease, asthma, diabetes, and hypertension, are associated with increased rates of preterm delivery, many of which are indicated because of maternal complications. History of cervical cone biopsy sample or loop electrocautery excision procedures secondary to premalignant cervical disorders have also been associated with an increase in spontaneous preterm delivery, as have various anomalies of the uterus itself—such as the presence of a septum.44

Mothers experiencing high levels of psychological or social stress are at increased risk of preterm birth (generally <2–fold) even after adjustment for the effects of sociodemographic, medical, and behavioural risk factors.45, 46 Furthermore, exposure to objectively stressful conditions, such as housing instability and severe material hardship, has also been associated with preterm birth.47 Although the mechanism underlying the association between psychological or social stress and increased risk of preterm birth is unknown, a role for corticotropin releasing hormone has been proposed. 48, 49, 50 Women exposed to stressful conditions also have increased serum concentrations of inflammatory markers—such as C-reactive protein—an observation not accounted for by other established risk factors for inflammation.51 These findings suggest that systemic inflammation might be a pathway by which stress could increase the risk of preterm birth.

Clinical depression during pregnancy has been reported in up to 16% of women, with up to 35% having some depressive symptoms.52, 53 Although the results are inconsistent, several reports suggest a relation (risks generally rose <2–fold) between depression and preterm birth.54, 55 Depression is associated with an increase in smoking, and drug and alcohol use; therefore, the relation between depression and preterm birth might be mediated by these behaviours.56, 57, 58 Nevertheless, in some studies that adjusted for smoking and drug and alcohol use, the association between depression and preterm birth persisted, suggesting that this relationship might be caused by more than confounding. Although, the mechanism(s) underlying the association of depression and preterm birth is unknown, there is an association between depressed mood and a reduction in natural killer cell activity, and higher plasma concentrations of proinflammatory cytokines and their receptors.59 Inflammation, therefore, might also partly mediate the relation between depression and preterm birth.

In the USA, about 20–25% of pregnant women smoke, and, of these, 12–15% continue throughout pregnancy.60, 61, 62 Tobacco use increases the risk of preterm birth (<2–fold) after adjustment for other factors.61, 62 The mechanism(s) by which smoking is related to preterm birth is unclear. There are more than 3000 chemicals in cigarette smoke and the biological effects of most are unknown;63 however, both nicotine and carbon monoxide are powerful vasoconstrictors, and are associated with placental damage and decreased uteroplacental blood flow. Both pathways lead to fetal growth restriction and indicated preterm births. Smoking is also associated with a systemic inflammatory response and can increase spontaneous preterm birth through that pathway.64, 65 Although heavy alcohol consumption has been associated with preterm birth, neither mild nor moderate alcohol use is generally regarded as a risk factor for preterm birth. Cocaine and heroin use have been associated with preterm birth in several studies.

Intrauterine infection is a frequent and important mechanism leading to preterm birth.66, 67 The mechanisms by which intrauterine infections lead to preterm labour are related to activation of the innate immune system.68 Microorganisms are recognised by pattern-recognition receptors—eg, toll-like receptors, which in turn elicit the release of inflammatory chemokines and cytokines—such as interleukin 8, interleukin 1β, and tumour necrosis factor (TNF) α. Microbial endotoxins and proinflammatory cytokines stimulate the production of prostaglandins, other inflammatory mediators, and matrix-degrading enzymes. Prostaglandins stimulate uterine contractility, whereas degradation of extracellular matrix in the fetal membranes leads to PPROM.67, 68

Microbiological studies suggest that intrauterine infection might account for 25–40% of preterm births;67 however, 25–40% might be a minimum estimate because intrauterine infection is difficult to detect with conventional culture techniques.69 Several investigators have shown additional microbial footprints in the amniotic cavity by using molecular microbiological techniques70, 71, 72—eg, women with a positive amniotic fluid Ureaplasma urealyticum PCR, but a negative culture, have similar rates of preterm birth to women with positive cultures for the same microorganism.73 Furthermore, since the rate of microbial colonisation of the chorioamnion is twice that seen in the amniotic cavity, rates of intrauterine infection based only on amniotic fluid cultures substantially underestimate the level of association.74

Accumulating evidence suggests that intra-amniotic infection is a chronic process.67 Women with positive U urealyticum amniotic fluid cultures or who are PCR-positive for U urealyticum at the time of midtrimester genetic amniocentesis often have spontaneous preterm labour or PPROM weeks after the procedure.75, 76, 77 Importantly, the earlier the gestational age at which women present with preterm labour, the higher the frequency of intrauterine infection.78, 79 At 21–24 weeks' gestation, most spontaneous births are associated with histological chorioamnionitis compared with about 10% at 35–36 weeks.78, 79

The microorganisms most commonly reported in the amniotic cavity are genital Mycoplasma spp, and, specifically, U urealyticum, but many other organisms have been identified.80, 81, 82, 83 Some common lower genital tract microorganisms, such as Streptococcus agalactiae, are rarely seen in the amniotic cavity before membrane rupture.67, 84 The genital mycoplasmas and other organisms detected in the uterus before membrane rupture are typically of low virulence, probably accounting for both the chronicity of intrauterine infections and the frequent absence of overt clinical signs of infection.67

Intrauterine infection can be confined to the decidua, extend to the space between the amnion and chorion, and reach the amniotic cavity and the fetus.67, 68 The amniotic cavity is usually sterile for bacteria, but the significance of microorganisms in the membranes is less clear. Bacteria have been cultured from the chorioamnion in 15% of non-labouring women with intact membranes undergoing indicated caesarean delivery.67 Fluorescence in-situ hybridisation with a DNA probe specific for conserved regions of bacterial DNA (the 16S ribosomal RNA) has detected bacteria in the membranes of up to 70% of women undergoing elective caesarean section at term.85 These findings suggest that the presence of bacteria in the chorioamnion alone cannot be sufficient to cause an inflammatory response, preterm labour, and preterm birth.85 Nevertheless, bacteria in the membranes and an associated inflammatory response in the amniotic fluid have been identified in more than 80% of women in early preterm labour with intact membranes who underwent caesarean section.68 Thus, bacterial infection probably predisposes to preterm birth.

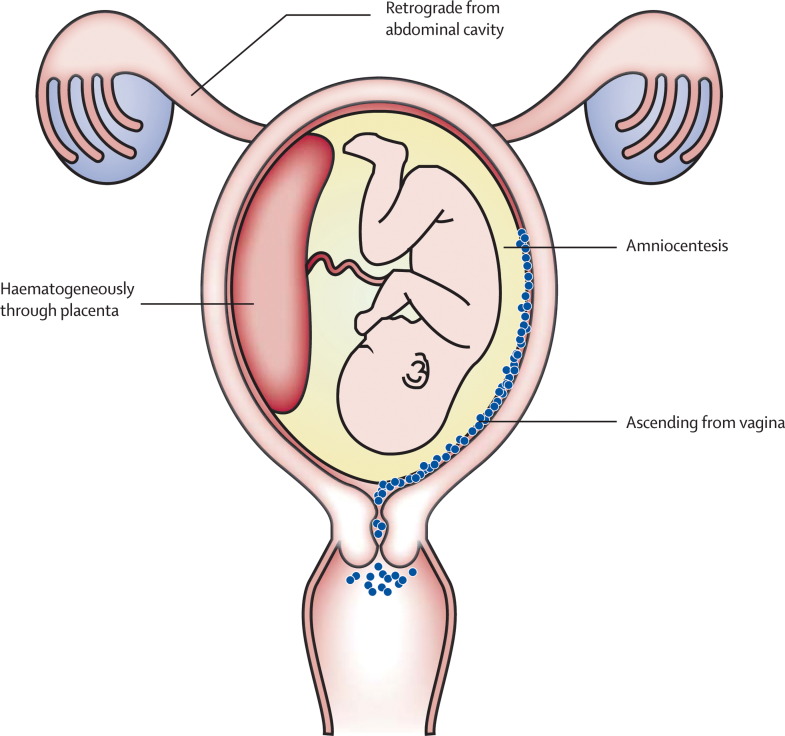

Microorganisms can gain access to the amniotic cavity by: (1) ascending from the vagina and the cervix; (2) haematogenous dissemination through the placenta; (3) accidental introduction at the time of invasive procedures; and (4) by retrograde spread through the fallopian tubes (figure 5 ).67, 86 The most common pathway is the ascending route. Although most investigators believe that ascent happens during the second trimester, the timing is unknown; some women have asymptomatic endometrial colonisation before pregnancy.87 Irrespective of when colonisation occurs, the hypothesis is that only when the membranes become tightly applied to the decidua at about 20 weeks' gestation, essentially forming an abscess, do colonised women become symptomatic and progress to early preterm birth.67

Figure 5.

Potential routes of intrauterine infection

The most advanced and serious stage of ascending intrauterine infection is fetal infection. Carroll and colleagues88 reported that fetal bacteraemia is present in 33% of fetuses with positive amniotic fluid cultures versus 4% with negative cultures. In another study, genital mycoplasma species were detected in 23% of umbilical cord cultures from infants born at less than 32 weeks' gestation.89 Both studies suggest that subclinical fetal infection is far more common than traditionally recognised. Microbial invasion of the amniotic cavity is frequently associated with intra-amniotic inflammation and a fetal inflammatory response.90, 91 The fetal inflammatory response has been linked to the onset of preterm labour, and fetal injury and long-term handicap—including periventricular leucomalacia, cerebral palsy, and chronic lung disease.92, 93, 94

Bacterial vaginosis—a disorder defined by a change in the microbial ecosystem of the vagina—is diagnosed clinically by the presence of clue cells, a vaginal pH greater than 4·5, a profuse white discharge, and a fishy odour when the vaginal discharge is exposed to potassium hydroxide.95 In the laboratory, bacterial vaginosis is defined by the Nugent criteria in which gram-stained smears are scored on the basis of numbers of lactobacilli, which tend to be low, and the presence of organisms resembling mobiluncus and bacteroides, the numbers of which tend to be high.96 A score of 7–10 is used to diagnose bacterial vaginosis, and has been associated with a 1·5-fold to 3-fold increase in the rate of preterm birth.97, 98 Black women in both the USA and the UK are three times more likely to have bacterial vaginosis than are white women, and this difference might explain 50% of the excess preterm births in black women.21, 99, 100 The mechanism by which bacterial vaginosis is associated with preterm birth is unknown, but microorganisms that cause the infection probably ascend into the uterus before or early during pregnancy.101, 102

Whether other genital infections are causally associated with preterm birth is not always clear.103, 104 For many infections, a range of associations has been reported, varying from none to strong. Women with genital infections generally have other risk factors, and many studies have not considered confounding variables. Nevertheless, trichomoniasis seems to be associated with preterm birth with a relative risk (RR) of about 1·3.105 Chlamydia is probably associated with preterm birth only in the presence of a maternal immune response, and most probably with a RR of about 2.106 Syphilis and gonorrhoea are probably associated with preterm birth with a RR of about 2.107 Vaginal group B streptococcus, U urealyticum, and M hominus colonisations are not associated with increased risk of preterm birth.103, 104

Several non-genital tract infections, such as pyelonephritis and asymptomatic bacteriuria, pneumonia, and appendicitis, are associated with, and probably predispose to, preterm birth.103, 108 Periodontal disease has received widespread scrutiny with some case-control studies suggesting an increased risk independent of other factors.109, 110 One potential explanation for the relation is that gingival crevice organisms, by way of maternal bacteraemia and transplacental passage, result in an intrauterine infection;111 however, after adjustment for other factors, periodontal disease associated with preterm birth was not related to increased intrauterine bacterial colonisation or histological chorioamnionitis.112 The biological pathway underlying the relation between periodontal disease and preterm births remains elusive.

Compared with bacterial infections, there is sparse evidence that viral infections predispose to preterm birth; however, when the mother is severely ill, such as with varicella pneumonia or severe acute respiratory syndrome, a preterm delivery might occur.113, 114 In several studies, the viral DNAs—identified by PCR techniques—in the amniotic fluid of asymptomatic women undergoing genetic amniocentesis were generally unrelated to subsequent preterm births;115 therefore, it seems unlikely that maternal viral infection plays an important part in preterm birth, but controversy persists, and with little information, further study is needed.116

Several studies have shown an association between uterine contraction frequency and preterm birth;117, 118, 119 however, uterine contractions do not predict preterm birth well in singletons because of the wide variation in frequency in normal pregnancy and the large overlap in frequency between women who do and do not deliver preterm.119 Newman and colleagues120 reported similar results in a study in twins; however, women admitted with a diagnosis of preterm labour, if they do not deliver, remain at increased risk of subsequent preterm labour and PPROM.

As labour approaches, the cervix shortens, softens, rotates anteriorly, and dilates. Both digital and ultrasound examinations of the cervix have shown that cervical shortening is a risk factor for preterm delivery.121, 122, 123 Ultrasound has proven especially useful in two circumstances: the first is in asymptomatic women, whereas the second is in those presenting with contractions. In asymptomatic women, at 24 weeks' gestation, a cervical length of less than 25 mm defines increased risk of preterm birth. The shorter the cervix, the greater the risk.122, 123 Women with preterm contractions often present a clinical dilemma, since nearly 60% of such women will, without treatment, deliver at term. Such women are usually observed for several hours before a decision is made to initiate tocolytic treatment, give corticosteroids, or discharge the patient. Cervical length can discriminate between women not in labour and those who carry a pronounced risk of early delivery. With a cervical length greater than 30 mm, the likelihood of delivering in the next week is about 1%, and most women can be safely discharged without treatment.124

Cervical insufficiency caused by congenital cervical weakness, surgery, or trauma has been implicated as causal for some preterm births; however, distinguishing cervical insufficiency from cervical shortening attributable to other causes has proven difficult, and the exact contribution to preterm birth is unknown.125

Biological and genetic markers

Biological fluids (eg, amniotic fluid, urine, cervical mucus, vaginal secretions, serum or plasma, or both, and saliva) have been used to assess the value of biomarkers for the prediction of preterm birth.21, 126 Cytokines, chemokines, oestriol, and other analytes have been assessed, and many, especially those related to inflammation, are associated with preterm birth. Studies of biomarkers have improved the understanding of the mechanisms of disease leading to spontaneous preterm birth, but few biomarkers have shown clinical usefulness.21 An important consideration is that, besides the specific nature of the analyte and its origin, an understanding of timing related to gestational age of collection and delivery is also necessary. For example, the concentration of matrix metalloproteinase-9 in serum rises substantially about 24 h before labour initiation.127 Such late prediction is of little value in prevention, but can aid in understanding the pathophysiology of preterm labour. Salivary oestriol concentration predicts late preterm birth quite well, but is not especially useful for the prediction of earlier preterm births.128 Prediction of late preterm births is of little importance because morbidity in these births is low.

The most powerful biochemical preterm birth predictor identified to date is fetal fibronectin—a glycoprotein that when present in cervicovaginal fluid is a marker of choriodecidual disruption.129 Typically, fetal fibronectin is absent from cervicovaginal secretions from 24 weeks' until near term; however, 3–4% of women undergoing routine screening at 24–26 weeks' are positive, and are at substantially increased risk of preterm delivery. For clinical care, an important characteristic of the fetal fibronectin test is its negative predictive value. In questionable cases of preterm labour, only about 1% of women with a negative test deliver in the next week.130

Each mechanism of disease responsible for preterm labour and PPROM has the potential for a genetic component. Women with sisters who gave birth preterm have an 80% higher risk of delivering preterm themselves.131 Grandparents of women having a preterm birth are significantly more likely to have been born preterm themselves.132 Genetic association studies have been used to identify single-nucleotide polymorphisms in several genes associated with preterm labour and PPROM.133, 134, 135 The fetal and maternal genotypes modify the risk of preterm delivery.135 A gene-environment interaction has been shown with maternal carriage of an allele of the TNFα gene and bacterial vaginosis.136 Although neither characteristic alone was associated with spontaneous preterm birth, the combination increased the risk of preterm birth. Similarly, maternal carriage of a polymorphism in the IL6 gene did not result in increased risk of spontaneous preterm birth for white or black women;137 however, black women who were carriers of the IL6 allele and had bacterial vaginosis had a two-fold greater risk of preterm birth than did those who carried the variant but did not have such infection. An interaction between maternal smoking and gene polymorphism on birthweight has also been described.138

The data provide evidence for gene-environment interactions in spontaneous preterm birth. Technological advances and completion of the HapMap project have made possible the conduction of whole-genome association studies;139 therefore, genetics is evolving from a candidate gene approach in which the DNA variants of biologically interesting genes are studied to a true genomic approach that aims to examine the entire genome. High-density arrays now allow simultaneous examination of 500 000 or more DNA variants in the same individual. Such studies have not been undertaken in relation to preterm birth.

The proteome is the entire set of proteins encoded by the genome, and proteomics is the study of the global set of proteins.140 Analysis of amniotic fluid and serum from women with preterm labour and PPROM has been undertaken to identify biomarkers for preterm labour and PPROM. In one study, bacteria were inoculated into the amniotic fluid of rhesus monkeys and the proteomic response monitored over time;141 several novel infection markers were identified. The same proteins were identified in amniotic fluid of pregnant women with chorioamnionitis-associated preterm labour. Thus, proteomic techniques can be used to identify biomarkers in women with premature labour and PPROM.

Additional research that clearly defines the mechanisms by which risk factors are related to preterm birth is crucial. Improved understanding of these mechanisms should allow clinicians to design appropriate interventions so that the incidence of preterm birth and related fetal and neonatal morbidity and mortality will be reduced.

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

Conflict of interest statement

References

- 1.Slattery MM, Morrison JJ. Preterm delivery. Lancet. 2002;360:1489–1497. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(02)11476-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hamilton BE, Martin JA, Ventura SJ. Births: preliminary data for 2005. Health E-Stats. Hyattsville, MD, 2006. http://www.cdc.gov/nchs/products/pubs/pubd/hestats/prelimbirths05/prelimbirths05.htm (accessed July 15, 2007). [PubMed]

- 3.Goldenberg RL, Rouse DJ. The prevention of premature birth. N Engl J Med. 1998;339:313–320. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199807303390506. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Iams JD, Romero R, Culhane JF, Goldenberg RL. The prevention of preterm birth. Lancet (in press).

- 5.McCormick MC. The contribution of low birth weight to infant mortality and childhood morbidity. N Engl J Med. 1985;312:82–90. doi: 10.1056/NEJM198501103120204. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Saigal S, Doyle LW An overview of mortality and sequelae of preterm birth from infancy to adulthood. Lancet (in press). [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Tucker JM, Goldenberg RL, Davis RO, Copper RL, Winkler CL, Hauth JC. Etiologies of preterm birth in an indigent population: is prevention a logical expectation? Obstet Gynecol. 1991;77:343–347. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ananth CV, Vintzileos AM. Epidemiology of preterm birth and its clinical subtypes. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;19:773–782. doi: 10.1080/14767050600965882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ananth CV, Joseph KS, Oyelese Y, Demissie K, Vintzileos AM. Trends in preterm birth and perinatal mortality among singletons: United States, 1989 through 2000. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;105:1084–1091. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000158124.96300.c7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jackson RA, Gibson KA, Wu YW, Croughan MS. Perinatal outcomes in singletons following in vitro fertilization: a meta–analysis. Obstet Gynecol. 2004;103:551–563. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000114989.84822.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Demissie K, Rhoads GG, Ananth CV. Trends in preterm birth and neonatal mortality among blacks and whites in the United States from 1989 to 1997. Am J Epidemiol. 2001;154:307–315. doi: 10.1093/aje/154.4.307. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mercer BM, Goldenberg RL, Meis PJ. The preterm prediction study: prediction of preterm premature rupture of membranes through clinical findings and ancillary testing. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;183:738–745. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.106766. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Romero R, Quintero R, Oyarzun E. Intraamniotic infection and the onset of labor in preterm premature rupture of the membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;159:661–666. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(88)80030-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Liggins GC, Fairclough RJ, Grieves SA, Forster CS, Knox BS. Parturition in the sheep. Ciba Found Symp. 1977;47:5–30. doi: 10.1002/9780470720295.ch2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Anderson AB, Laurence KM, Turnbull AC. The relationship in anencephaly between the size of the adrenal cortex and the length of gestation. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1969;76:196–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1969.tb05821.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sfakianaki AK, Norwitz ER. Mechanisms of progesterone action in inhibiting prematurity. J Matern Fetal Neonatal Med. 2006;19:763–772. doi: 10.1080/14767050600949829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Garfield RE, Gasc JM, Baulieu EE. Effects of the antiprogesterone RU 486 on preterm birth in the rat. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;157:1281–1285. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(87)80315-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Meis PJ, Klebanoff M, Thom E. Prevention of recurrent preterm delivery by 17 alpha–hydroxyprogesterone caproate. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:2379–2385. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa035140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Romero R, Espinoza J, Kusanovic J. The preterm parturition syndrome. BJOG. 2006;113:17–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF. Prepregnancy health status and the risk of preterm delivery. Arch Pediatr Adolesc Med. 2005;159:89–90. doi: 10.1001/archpedi.159.1.89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Goldenberg RL, Goepfert AR, Ramsey PS. Biochemical markers for the prediction of preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:S36–S46. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Goldenberg RL, Cliver SP, Mulvihill FX. Medical, psychosocial, and behavioral risk factors do not explain the increased risk for low birth weight among black women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1317–1324. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70048-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fiscella K. Race, perinatal outcome, and amniotic infection. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 1996;51:60–66. doi: 10.1097/00006254-199601000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Collins JW, Jr, Hawkes EK. Racial differences in post-neonatal mortality in Chicago: what risk factors explain the black infant's disadvantage? Ethn Health. 1997;2:117–125. doi: 10.1080/13557858.1997.9961820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Smith LK, Draper ES, Manktelow BN, Dorling JS, Field DJ. Socioeconomic inequalities in very preterm birth rates. Arch Dis Child Fetal Neonatal Ed. 2007;92:F11–F14. doi: 10.1136/adc.2005.090308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Brett KM, Strogatz DS, Savitz DA. Employment, job strain, and preterm delivery among women in North Carolina. Am J Public Health. 1997;87:199–204. doi: 10.2105/ajph.87.2.199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Thompson JM, Irgens LM, Rasmussen S, Daltveit AK. Secular trends in socio-economic status and the implications for preterm birth. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2006;20:182–187. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2006.00711.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saurel-Cubizolles MJ, Zeitlin J, Lelong N, Papiernik E, Di Renzo GC, Breart G, for the Europop Group Employment, working conditions, and preterm birth: results from the Europop case-control survey. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2004;58:395–401. doi: 10.1136/jech.2003.008029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Launer LJ, Villar J, Kestler E, de Onis M. The effect of maternal work on fetal growth and duration of pregnancy: a prospective study. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1990;97:62–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1990.tb01718.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pompeii LA, Savitz DA, Evenson KR, Rogers B, McMahon M. Physical exertion at work and the risk of preterm delivery and small-for-gestational-age birth. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1279–1288. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000189080.76998.f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Newman RB, Goldenberg RL, Moawad AH. Occupational fatigue and preterm premature rupture of membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2001;184:438–446. doi: 10.1067/mob.2001.110312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Conde-Agudelo A, Rosas-Bermudez A, Kafury-Goeta AC. Birth spacing and risk of adverse perinatal outcomes: a metaanalysis. JAMA. 2006;295:1809–1823. doi: 10.1001/jama.295.15.1809. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Smith GC, Pell JP, Dobbie R. Interpregnancy interval and risk of preterm birth and neonatal death: retrospective cohort study. BMJ. 2003;327:313. doi: 10.1136/bmj.327.7410.313. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tamura T, Goldenberg RL, Freeberg LE, Cliver SP, Cutter GR, Hoffman HJ. Maternal serum folate and zinc concentrations and their relationship to pregnancy outcome. Am J Clin Nutr. 1992;56:365–370. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/56.2.365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Hendler I, Goldenberg RL, Mercer BM. The preterm prediction study: association between maternal body mass index (BMI) and spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;192:882–886. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.09.021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Scholl TO. Iron status during pregnancy: setting the stage for mother and infant. Am J Clin Nutr. 2005;81:1218S–1222S. doi: 10.1093/ajcn/81.5.1218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Neggers Y, Goldenberg RL. Some thoughts on body mass index, micronutrient intakes and pregnancy outcome. J Nutr. 2003;133:1737S–1740S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1737S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Goldenberg RL. The plausibility of micronutrient deficiency in relationship to perinatal infection. J Nutr. 2003;133:1645S–1648S. doi: 10.1093/jn/133.5.1645S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Goldenberg RL, Tamura T. Prepregnancy weight and pregnancy outcome. JAMA. 1996;275:1127–1128. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Mercer BM, Goldenberg RL, Moawad AH. The preterm prediction study: effect of gestational age and cause of preterm birth on subsequent obstetric outcome. National Institute of Child Health and Human Development Maternal-Fetal Medicine Units Network. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:1216–1221. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70111-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Goldenberg RL, Andrews WW, Faye-Petersen O, Cliver SP, Goepfert A, Hauth JC. The Alabama preterm birth project: placental histology in recurrent spontaneous and indicated preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:792–796. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.05.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Ananth CV, Getahun D, Peltier MR, Salihu HM, Vintzileos AM. Recurrence of spontaneous versus medically indicated preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:643–650. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.05.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Krupa FG, Faltin D, Cecatti JG, Surita FG, Souza JP. Predictors of preterm birth. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2006;94:5–11. doi: 10.1016/j.ijgo.2006.03.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Jakobsson M, Gissler M, Sainio S, Paavonen J, Tapper AM. Preterm delivery after surgical treatment for cervical intraepithelial neoplasia. Obstet Gynecol. 2007;109:309–313. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000253239.87040.23. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Copper RL, Goldenberg RL, Das A. The preterm prediction study: maternal stress is associated with spontaneous preterm birth at less than thirty-five weeks gestation. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1286–1292. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70042-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Lobel M, Dunkerl-Schetter C, Scrimshaw SC. Prenatal maternal stress and prematurity: a prospective study of socioeconomically disadvantaged women. Health Psychol. 1992;11:32–40. doi: 10.1037//0278-6133.11.1.32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Farley TA, Mason K, Rice J, Habel JD, Scribner R, Cohen DA. The relationship between the neighbourhood environment and adverse birth outcomes. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2006;20:188–200. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.2006.00719.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Wadhwa PD, Culhane JF, Rauh V, Narve SS. Stress and preterm birth: neuroendocrine, immune/inflammatory, and vascular mechanisms. Matern Child Health J. 2001;5:119–125. doi: 10.1023/a:1011353216619. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Wadhwa PD, Culhane JF, Rauh V. Stress, infection and preterm birth: a biobehavioural perspective. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 2001;15:17–29. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-3016.2001.00005.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Challis JR, Smith SK. Fetal endocrine signals and preterm labour. Biol Neonate. 2001;79:163–167. doi: 10.1159/000047085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Sheldon J, Riches P, Gooding R, Soni N, Hobb JR. C-reactive protein and its cytokine mediators in intensive-care patients. Clin Chem. 1993;39:147–150. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gavin NI, Gaynes BN, Lohr KN, Meltzer-Brody S, Gartlehner G, Swinson T. Perinatal depression: a systematic review of prevalence and incidence. Obstet Gynecol. 2005;106:1071–1083. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000183597.31630.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Dayan J, Creveuil C, Marks MN. Prenatal depression, prenatal anxiety, and spontaneous preterm birth: a prospective cohort study among women with early and regular care. Psychosom Med. 2006;68:938–946. doi: 10.1097/01.psy.0000244025.20549.bd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Orr ST, Miller CA. Maternal depressive symptoms and the risk of poor pregnancy outcome: review of the literature and preliminary findings. Epidemiol Rev. 1995;17:165–171. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036172. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hoffman S, Hatch MC. Stress, social support and pregnancy outcome: a reassessment based on recent research. Paediatr Perinat Epidemiol. 1996;10:380–405. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3016.1996.tb00063.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Orr ST, James SA, Prince CB. Maternal prenatal depressive symptoms and spontaneous preterm births among African-American women in Baltimore, Maryland. Am J Epidemiol. 2002;156:797–802. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwf131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Schoenborn CA, Horm J. Negative moods as correlates of smoking and heavier drinking: implications for health promotion. Adv Data. 1993;236:1–16. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Zuckerman B, Amaro H, Bauchner H, Cabral H. Depressive symptoms during pregnancy: relationship to poor health behaviors. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;160:1107–1111. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90170-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Gennaro S, Fehder W, Nuamah IF, Campbell DE, Douglas SD. Caregiving to very low birthweight infants: a model of stress and immune response. Brain Behav Immun. 1997;11:201–215. doi: 10.1006/brbi.1997.0502. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Ebrahim SH, Floyd RL, Merritt RK, Decoufle P, Holtzman D. Trends in pregnancy related smoking rates in the United States, 1987–1996. JAMA. 2000;283:361–366. doi: 10.1001/jama.283.3.361. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Andres RL, Day MC. Perinatal complications associated with maternal tobacco use. Semin Neonatol. 2000;5:231–241. doi: 10.1053/siny.2000.0025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Cnattingius S. The epidemiology of smoking during pregnancy: smoking prevalence, maternal characteristics, and pregnancy outcomes. Nicotine Tob Res. 2004;6:S125–S140. doi: 10.1080/14622200410001669187. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Benowitz NL, Dempsey DA, Goldenberg RL. The use of pharmacotherapies for smoking cessation during pregnancy. Tob Control. 2000;9(suppl 3):iii91–iii94. doi: 10.1136/tc.9.suppl_3.iii91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Tracy RP, Psaty BM, Macy E. Lifetime smoking exposure affects the association of C-reactive protein with cardiovascular disease risk factors and subclinical disease in healthy elderly subjects. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 1997;17:2167–2176. doi: 10.1161/01.atv.17.10.2167. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Bermudez EA, Rifai N, Buring JE, Manson JE, Ridker PM. Relation between markers of systemic vascular inflammation and smoking in women. Am J Cardiol. 2000;89:1117–1119. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9149(02)02284-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Knox IC, Jr, Hoerner JK. The role of infection in premature rupture of the membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1950;59:190–194. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(50)90370-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC, Andrews WW. Intrauterine infection and preterm delivery. N Engl J Med. 2000;342:1500–1507. doi: 10.1056/NEJM200005183422007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Romero R, Espinoza J, Kusanovic JP. The preterm parturition syndrome. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;113:17–42. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01120.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Relman DA, Loutit JS, Schmidt RM, Falkow S, Tompkins LS. The agent of bacillary angiomatosis. An approach to the identification of uncultured pathogens. N Engl J Med. 1990;323:1573–1580. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199012063232301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Jalava J, Mantymaa ML, Ekblad U. Bacterial 16S rDNA polymerase chain reaction in the detection of intra-amniotic infection. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;103:664–669. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1996.tb09835.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hitti J, Riley DE, Krohn MA. Broad-spectrum bacterial rDNA polymerase chain reaction assay for detecting amniotic fluid infection among women in premature labor. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:1228–1232. doi: 10.1086/513669. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Gardella C, Riley DE, Hitti J, Agnew K, Krieger JN, Eschenbach D. Identification and sequencing of bacterial rDNAs in culture-negative amniotic fluid from women in premature labor. Am J Perinatol. 2004;21:319–323. doi: 10.1055/s-2004-831884. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Yoon BH, Romero R, Lim JH. The clinical significance of detecting Ureaplasma urealyticum by the polymerase chain reaction in the amniotic fluid of patients with preterm labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2003;189:919–924. doi: 10.1067/s0002-9378(03)00839-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Cassell G, Andrews W, Hauth J. Isolation of microorganisms from the chorioamnion is twice that from amniotic fluid at cesarean delivery in women with intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1993;168:424. [Google Scholar]

- 75.Cassell GH, Davis RO, Waites KB. Isolation of Mycoplasma hominis and Ureaplasma urealyticum from amniotic fluid at 16–20 weeks of gestation: potential effect on outcome of pregnancy. Sex Transm Dis. 1983;10:294–302. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Horowitz S, Mazor M, Romero R. Infection of the amniotic cavity with Ureaplasma urealyticum in the midtrimester of pregnancy. J Reprod Med. 1995;40:375–379. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Gray DJ, Robinson HB, Malone J. Adverse outcome in pregnancy following amniotic fluid isolation of Ureaplasma urealyticum. Prenat Diagn. 1992;12:111–117. doi: 10.1002/pd.1970120206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Russell P. Inflammatory lesions of the human placenta. I. Clinical significance of acute chorioamnionitis. Diagn Gynecol Obstet. 1979;1:127–137. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mueller-Heubach E, Rubinstein DN, Schwarz SS. Histologic chorioamnionitis and preterm delivery in different patient populations. Obstet Gynecol. 1990;75:622–626. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Watts DH, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. The association of occult amniotic fluid infection with gestational age and neonatal outcome among women in preterm labor. Obstet Gynecol. 1992;79:351–357. doi: 10.1097/00006250-199203000-00005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Gibbs RS, Romero R, Hillier SL. A review of premature birth and subclinical infection. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1992;166:1515–1528. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(92)91628-n. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Romero R, Sirtori M, Oyarzun E. Infection and labor. V. Prevalence, microbiology, and clinical significance of intraamniotic infection in women with preterm labor and intact membranes. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1989;161:817–824. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(89)90409-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Andrews WW, Hauth JC, Goldenberg RL. Amniotic fluid interleukin-6: correlation with upper genital tract microbial colonization and gestational age in women delivered following spontaneous labor versus indicated delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:606–612. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)90290-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Andrews WW, Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC. Preterm labor: emerging role of genital tract infections. Infect Agents Dis. 1995;4:196–211. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Steel JH, Malatos S, Kennea N. Bacteria and inflammatory cells in fetal membranes do not always cause preterm labor. Pediatr Res. 2005;57:404–411. doi: 10.1203/01.PDR.0000153869.96337.90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Gomez R, Romero R, Mazor M, Ghezzi F, David C, Yoon BH. The role of infection in preterm labor and delivery. In: Elder M, Romero R, Lamont R, editors. Preterm Labor. Churchill Livingstone; London: 1997. pp. 85–125. [Google Scholar]

- 87.Andrews WW, Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC, Cliver SP, Conner M, Goepfert AR. Endometrial microbial colonization and plasma cell endometritis after spontaneous or indicated preterm versus term delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2005;193:739–745. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2005.02.128. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Carroll SG, Papaioannou S, Ntumazah IL, Philpott-Howard J, Nicolaides KH. Lower genital tract swabs in the prediction of intrauterine infection in preterm prelabour rupture of the membranes. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 1996;103:54–59. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1996.tb09515.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Goldenberg RL, Andrews WW, Goepfert AR, et al. The Alabama preterm birth study: umbilical cord blood Ureaplasma urealyticum and Mycoplasma hominis cultures in very preterm newborns. Am J Obstet Gynecol (in press). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 90.Gomez R, Romero R, Ghezzi F, Yoon BH, Mazor M, Berry SM. The fetal inflammatory response syndrome (FIRS) Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:194–202. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70272-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Romero R, Gomez R, Ghezzi F. A fetal systemic inflammatory response is followed by the spontaneous onset of preterm parturition. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1998;179:186–193. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(98)70271-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Yoon BH, Romero R, Yang SH. Interleukin-6 concentrations in umbilical cord plasma are elevated in neonates with white matter lesions associated with periventricular leukomalacia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;174:1433–1440. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70585-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Yoon BH, Romero R, Park JS. Fetal exposure to an intra-amniotic inflammation and the development of cerebral palsy at the age of three years. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2000;182:675–681. doi: 10.1067/mob.2000.104207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Yoon BH, Romero R, Kim KS. A systemic fetal inflammatory response and the development of bronchopulmonary dysplasia. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:773–779. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70299-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Amstel R, Totten PA, Speigel CA. Nonspecific vaginitis: diagnostic criteria and microbial and epidemiologic associations. Am J Med. 1983;74:14–22. doi: 10.1016/0002-9343(83)91112-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Nugent RP, Krohn MA, Hillier SL. Reliability of diagnosing bacterial vaginosis is improved by a standardized method of gram stain interpretation. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:297–301. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.2.297-301.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Meis PJ, Goldenberg RL, Mercer B. The preterm prediction study: significance of vaginal infections. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;173:1231–1235. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)91360-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hillier SL, Nugent RP, Eschenbach DA. Association between bacterial vaginosis and preterm delivery of a low-birthweight infant. The vaginal infections and prematurity study group. N Engl J Med. 1995;333:1737–1742. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199512283332604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Goldenberg RL, Klebanoff MA, Nugent R. Bacterial colonization of the vagina during pregnancy in four ethnic groups. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1996;175:1317–1324. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(96)70617-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Fiscella K. Racial disparities in preterm births. The role of urogenital infections. Public Health Rep. 1996;111:104–113. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Krohn MA, Hillier SL, Nugent RP. The genital flora of women with intraamniotic infection. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1475–1480. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.6.1475. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Hillier SL, Krohn MA, Cassen E. The role of bacterial vaginosis and vaginal bacteria in amniotic fluid infection in women in preterm labor with intact fetal membranes. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;20:S276–S278. doi: 10.1093/clinids/20.supplement_2.s276. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Goldenberg RL, Culhane JF, Johnson DC. Maternal infection and adverse fetal and neonatal outcomes. Clin Perinatol. 2005;32:523–559. doi: 10.1016/j.clp.2005.04.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Goldenberg RL, Andrews WW, Yuan AC. Sexually transmitted diseases and adverse outcomes of pregnancy. Clin Perinatol. 1997;24:23–41. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Cotch MF, Pastorek JG, 2nd, Nugent RP. Trichomonas vaginalis associated with low birth weight and preterm delivery. Sex Transm Dis. 1997;24:353–360. doi: 10.1097/00007435-199707000-00008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Sweet RL, Landers DL, Walker C. Chlamydia trachomatis infection and pregnancy outcome. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1987;156:824–833. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(87)90338-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Donders GG, Desmyter J, De Wet DH. The association of gonorrhea and syphilis with premature birth and low birth weight. Genitourin Med. 1993;69:98–101. doi: 10.1136/sti.69.2.98. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Romero R, Oyarzun E, Mazor M, Sirtori M, Hobbins JC, Bracken M. Meta-analysis of the relationship between asymptomatic bacteriuria and preterm delivery/low birth weight. Obstet Gynecol. 1989;73:576–582. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Offenbacher S, Katz V, Fertik G. Periodontal infection as a possible risk factor for preterm low birth weight. J Periodontol. 1996;67:1103–1113. doi: 10.1902/jop.1996.67.10s.1103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Jeffcoat MK, Geurs NC, Reddy MS, Cliver SP, Goldenberg RL, Hauth JC. Periodontal infection and preterm birth: results of a prospective study. J Am Dent Assoc. 2001;132:875–880. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2001.0299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Offenbacher S, Jared HL, O'Reilly PG. Potential pathogenic mechanisms of periodontitis associated pregnancy complications. Ann Periodontol. 1998;3:233–250. doi: 10.1902/annals.1998.3.1.233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Goepfert AR, Jeffcoat M, Andrews WW. Periodontal disease and upper genital tract inflammation in early spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;104:777–783. doi: 10.1097/01.AOG.0000139836.47777.6d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Hardy JMB, Azarowicz EN, Mannini A. The effect of Asian influenza on the outcome of pregnancy. Baltimore 1957–1958. Am J Public Health. 1961;51:1182–1188. doi: 10.2105/ajph.51.8.1182. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Horn P. Poliomyelitis in pregnancy. A twenty-year report from Los Angeles County, California. Obstet Gynecol. 1955;6:121–137. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Wenstrom KD, Andrews WW, Bowles NE. Intrauterine viral infection at the time of second trimester genetic amniocentesis. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:420–424. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00210-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Srinivas SK, Ma Y, Sammel MD. Placental inflammation and viral infection are implicated in second trimester pregnancy loss. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:797–802. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.05.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Moore TR, Iams JD, Creasy RK, Burau KD, Davidson AL. Diurnal and gestational patterns of uterine activity in normal human pregnancy. Obstet Gynecol. 1994;83:517–523. doi: 10.1097/00006250-199404000-00006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Nageotte MP, Dorchester W, Porto M, Keegan KA, Jr, Freeman RK. Quantitation of uterine activity preceding preterm, term, and postterm labor. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1988;158:1254–1259. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(88)90353-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Iams JD, Newman RB, Thom EA. Frequency of uterine contractions and the risk of spontaneous preterm delivery. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:250–255. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa002868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Newman RB, Iams JD, Das A. A prospective masked observational study of uterine contraction frequency in twins. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;195:1564–1570. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.03.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Copper RL, Goldenberg RL, Davis RO. Warning symptoms, uterine contractions, and cervical examination findings in women at risk of preterm delivery. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1990;162:748–754. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(90)91000-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Iams JD, Goldenberg RL, Meis PJ. The length of the cervix and the risk of spontaneous premature delivery. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:567–572. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199602293340904. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Andrews WW, Copper RL, Hauth JC, Goldenberg RL, Neely C, DuBard M. Second-trimester cervical ultrasound: associations with increased risk for recurrent early, spontaneous delivery. Obstet Gynecol. 2000;95:222–226. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00483-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 124.Leitich H, Brumbauer M, Kaider A. Cervical length and dilation of the internal as detected by vaginal ultrasonography as markers for preterm delivery: a systematic review. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1999;181:1465–1472. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9378(99)70407-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 125.Iams JD, Johnson FF, Sonek J. Cervical competence as a continuum: a study of ultrasonographic cervical length and obstetric performance. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1995;172:1097–1103. doi: 10.1016/0002-9378(95)91469-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 126.Moawad AH, Goldenberg RL, Mercer B. The preterm prediction study: the value of serum alkaline phosphatase, alpha-fetoprotein, plasma corticotropin-releasing hormone, and other serum markers for the prediction of spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2002;186:990–996. doi: 10.1067/mob.2002.121727. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 127.Tu FF, Goldenberg RL. Prenatal plasma matrix metalloproteinase–9 (MMP-9) levels as predictors of spontaneous preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 1998;92:446–449. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(98)00222-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 128.Ramsey PS, Andrews WW. Biochemical predictors of preterm labor: fetal fibronectin and salivary estriol. Clin Perinatol. 2003;30:701–733. doi: 10.1016/s0095-5108(03)00109-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 129.Goldenberg RL, Mercer BM, Meis PJ, Copper RL, Das A, McNellis D. The preterm prediction study: fetal fibronectin testing and spontaneous preterm birth. Obstet Gynecol. 1996;87:643–648. doi: 10.1016/0029-7844(96)00035-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 130.Lu GC, Goldenberg RL, Cliver SP, Kreaden US, Andrews WW. Vaginal fetal fibronectin levels and spontaneous preterm birth in symptomatic women. Obstet Gynecol. 2001;97:225–228. doi: 10.1016/s0029-7844(00)01130-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 131.Winkvist A, Mogren I, Hogberg U. Familial patterns in birth characteristics: impact on individual and population risks. Int J Epidemiol. 1998;27:248–254. doi: 10.1093/ije/27.2.248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 132.Porter TF, Fraser AM, Hunter CY, Ward RH, Varner MW. The risk of preterm birth across generations. Obstet Gynecol. 1997;90:63–67. doi: 10.1016/S0029-7844(97)00215-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 133.Engel SA, Erichsen HC, Savitz DA, Thorp J, Chanock SJ, Olshan AF. Risk of spontaneous preterm birth is associated with common proinflammatory cytokine polymorphisms. Epidemiology. 2005;16:469–477. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000164539.09250.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 134.Menon R, Velez DR, Simhan H. Multilocus interactions at maternal tumor necrosis factor-alpha, tumor necrosis factor receptors, interleukin-6 and interleukin-6 receptor genes predict spontaneous preterm labor in European-American women. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2006;194:1616–1624. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2006.03.059. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 135.Crider KS, Whitehead N, Buus RM. Genetic variation associated with preterm birth: a HuGE review. Genet Med. 2005;7:593–604. doi: 10.1097/01.gim.0000187223.69947.db. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 136.Macones GA, Parry S, Elkousy M, Clothier B, Ural SH, Strauss JF., III. A polymorphism in the promoter region of TNF and bacterial vaginosis: preliminary evidence of gene-environment interaction in the etiology of spontaneous preterm birth. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 2004;190:1504–1508. doi: 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 137.Engel SA, Erichsen HC, Savitz DA, Thorp J, Chanock SJ, Olshan AF. Risk of spontaneous preterm birth is associated with common proinflammatory cytokine polymorphisms. Epidemiology. 2005;16:469–477. doi: 10.1097/01.ede.0000164539.09250.31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 138.Wang X, Zuckerman B, Pearson C. Maternal cigarette smoking, metabolic gene polymorphism, and infant birth weight. JAMA. 2002;287:195–202. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.2.195. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 139.Harvesting the fruits of the human genome. Nat Genet. 2001;27:227–228. doi: 10.1038/85763. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 140.Romero R, Espinoza J, Gotsch F. The use of high-dimensional biology (genomics, transcriptomics, proteomics, and metabolomics) to understand the preterm parturition syndrome. Br J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006;113:118–135. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2006.01150.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 141.Gravett MG, Thomas A, Schneider KA. Proteomic analysis of cervical-vaginal fluid: identification of novel biomarkers for detection of intra-amniotic infection. J Proteome Res. 2007;6:89–96. doi: 10.1021/pr060149v. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]