Abstract

3C‐like (3CL) protease is essential for the life cycle of severe acute respiratory syndrome‐coronavirus (SARS‐CoV) and therefore represents a key anti‐viral target. A compound library consisting of 960 commercially available drugs and biologically active substances was screened for inhibition of SARS‐CoV 3CL protease. Potent inhibition was achieved using the mercury‐containing compounds thimerosal and phenylmercuric acetate, as well as hexachlorophene. As well, 1–10 μM of each compound inhibited viral replication in Vero E6 cell culture. Detailed mechanism studies using a fluorescence‐based protease assay demonstrated that the three compounds acted as competitive inhibitors (K

i=0.7, 2.4, and 13.7 μM for phenylmercuric acetate, thimerosal, and hexachlorophene, respectively). A panel of metal ions including Zn2+ and its conjugates were then evaluated for their anti‐3CL protease activities. Inhibition was more pronounced using a zinc‐conjugated compound (1‐hydroxypyridine‐2‐thione zinc;  M) than using the ion alone (

M) than using the ion alone ( M).

M).

Keywords: SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; SARS-CoV, SARS coronavirus; Dabcyl, 4-(4-dimethylaminophenylazo)benzoic acid; Edans, 5-[(2-aminoethyl)amino]naphthalene-1 sulfonic acid; Severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus; Cysteine protease; Fluorescent assay; Inhibitor screening; Metal ion; Ki

1. Introduction

Beginning in Guangdon province of China in late 2002, severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) caused by a novel human coronavirus (CoV) subsequently spread to over 25 countries [1, 2, 3, 4]. Subsequent analysis of the virus has revealed features that may be used in preventative or therapeutic strategies. Analogous to the 3C proteases encoded by picornaviruses, a virally encoded 3C‐like (3CL) protease that functions in the maturation of viral polyproteins is essential for the completion of the SARS‐CoV life cycle [5]. It is a chymotrypsin‐like protease that uses a Cys rather than a Ser residue as the nucleophile in the active site. The 3CL protease contains an additional helical C‐terminal domain of about 100 residues, absent from the analogous picornavirus 3C and chymotrypsin, which is essential for enzymatic activity. Its removal obviates proteolytic activity, since this critical domain is responsible for the dimerization of the protease, which is a prerequisite for proteolytic activity [6]. Moreover, the active site of the SARS‐CoV 3CL protease comprises a catalytic dyad rather than a triad.

The SARS‐CoV 3CL protease represents an obvious and key target for anti‐SARS strategies. Crystallization of the protease [7, 8] has led to the identification of several candidate inhibitors in computer modeling studies [9, 10] and biological assays [11]. However, to date, a detailed exploration of inhibitor activity has been lacking. Previously, we developed a fluorescence‐based assay suitable to screen inhibitors of the protease in a high throughput format [12, 13]. We used this system presently to screen a compound library consisting of 960 mostly commercially available drugs and biologically active substances. In light of previous reports, we were interested in examining the influence of metal‐conjugated compounds on protease activity [14, 15, 16]. As reported in this paper, several compounds inhibit SARS‐CoV 3CL protease including Zn‐conjugated compounds.

2. Materials and methods

2.1. Materials

A fluorogenic peptide substrate (Dabcyl‐KTSAVLQSGFRKME‐Edans) and SARS‐CoV 3CL protease were prepared as previously reported [12]. The protease was stored in the buffer containing 12 mM Tris–HCl (pH 7.5), 120 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, 7.5 mM β‐ME, and 1 mM DTT at −70 °C before use. The compound library was obtained from The Genesis Plus Collection (MicroSource Discovery Systems, Inc., Gaylordsville, CT). Many of the 960 compounds collected in this library are compounds approved by the United States Food and Drug Administration (FDA).

2.2. Western immunoblotting analysis

The ability of the tested compounds to inhibit SARS‐CoV replication was assayed using Vero E6 cells. Cells were infected with SARS‐CoV in the presence or absence of the particular test compound and incubated for two days at 37 °C in an atmosphere of 5% CO2. After two days, cells were harvested and lysed. Equal amounts (10 μl) of cell lysate were boiled in a sample loading buffer (125 mM Tris–HCl, pH 6.8, 100 mM DTT, 2% SDS, 20% glycerol, and 0.005% bromophenol blue) for 5 min and then loaded onto an 8% SDS–polyacrylamide gel. After electrophoresis, the proteins were transferred onto a Hybond‐C extra membrane using a semidry apparatus (Amersham Biosciences, Buckinghamshire, UK). The membranes were blocked with Blotto/Tween blocking buffer (5 mM Tris, pH 7.4, 77 mM NaCl, 0.05% Tween 20, 2.5% skimmed milk, and 0.001% antiform A) and then incubated with BALB/c anti‐rS268, which is an anti‐spike polyclonal antibody [17]. The membrane was then washed with blocking buffer and further incubated with goat anti‐mouse HRP‐conjugated secondary antibody. The membrane was finally washed with blocking buffer and developed with ECL Western Blotting Detection Reagent (Amersham Biosciences).

2.3. Cytotoxicity assay

Cell viability was determined by the tetrazolium salts (MTS) assay that was conducted essentially as described [18]. This convenient method is based on the conversion of MTS to a chromatic, soluble formazan in living cells, via the mitochondrial enzyme NAD‐dependent dehydrogenase. MTS and phenazine methosulfate were purchased from Sigma Chemical Co. (St. Louis, MO) or Promega (Madison, WI) as powders and were prepared in Dulbecco's phosphate‐buffered saline. Measurements at each drug concentration were performed with three repeats.

2.4. Inhibitor assay

The enhanced fluorescence due to proteolytically catalyzed cleavage of Dabcyl‐KTSAVLQSGFRKME‐Edans was monitored at 538 nm with excitation at 355 nm using a fluorescence plate reader (Fluoroskan Ascent; ThermoLabsystems, Helsinki, FINLAND). Substrate concentration was determined from the extinction coefficient of 5438 M−1 cm−1 at 336 nm (Edans) or 15 100 M−1 cm−1 at 472 nm (Dabcyl). The fluorimetric assay was utilized to identify inhibitors of SARS‐CoV 3CL protease and determine their inhibition constants. K i measurements were performed at two fixed inhibitor concentrations of 2 and 5 μM or 3 and 5 μM. Substrate concentrations ranged from 8 to 80 μM in a reaction mixture containing 50 nM SARS‐CoV protease. Lineweaver‐Burk plots of kinetic data were fitted with the computer program KinetAsyst II (IntelliKinetics, State College, PA) by non‐linear regression to obtain the K i value for competitive and non‐competitive inhibitor using Eqs. (1) and (2), respectively.

|

(1) |

|

(2) |

In these equations, K m is Michaelis constant of the substrate, K i is inhibition constant, V m is maximal velocity, and [I] and [S] represent the inhibitor and substrate concentrations in the reaction mixture, respectively.

3. Results

3.1. Influence of 3CL protease inhibitors

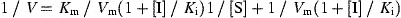

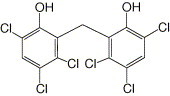

The compound library containing 960 compounds was screened for inhibition of the SARS‐CoV 3CL protease. Inhibition resulted from the application of the three hits, phenylmercuric acetate, thimerosal, and hexachlorophene. The influence of these compounds on viral protein production, as an indicator of replication, was then examined. As shown, Western blots revealed that 10 μM phenylmercuric acetate suppressed detection of the viral spike protein (Fig. 1 ). The actin level in Vero E6 cells treated with phenylmercuric acetate and then infected by SARS‐CoV was lower, indicating that at a concentration of 10 μM the compound might be toxic to the cells. The presence of 1 μM thimerosal diminished the detectable quantity of the spike protein by over 90 percent (Fig. 1). Similar observations were obtained using 10 μM hexachlorophene (Fig. 1). The latter two compounds displayed no apparent toxic effect, as evidenced by the unchanged actin levels. This hexachlorophene concentration also showed strong inhibition of cytopathic effect on virus‐infected Vero E6 cells (results not shown). No cytotoxicity was exhibited when Vero E6 cells were treated with 10 μM hexachlorophene (Fig. 2 ).

Figure 1.

Western blot analysis of the anti‐SARS‐CoV activity of three tested inhibitors. The inhibition of SARS‐CoV replication by the compounds is demonstrated by blocking the spike protein biosynthesis by the inhibitor. Actin serves as an indicator for cytotoxicity of the compounds. Phenylmercuric acetate is toxic to the Vero cells at the concentration of 10 μM but the other two compounds are not toxic at the concentrations tested. These inhibitors apparently work well in inhibiting the viral replication in the window of 1–10 μM.

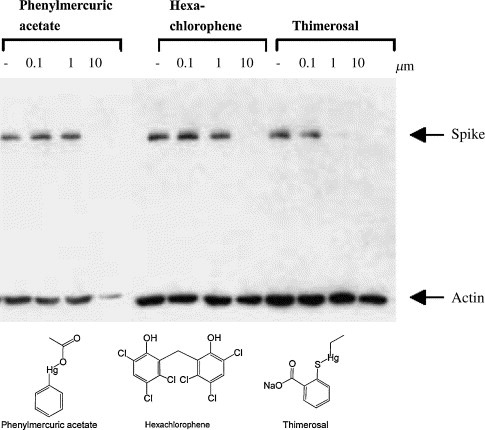

Figure 2.

The cytotoxicity assay. Hexachlorophene was found to possess potent anti‐SARS‐CoV activity at a concentration that did not cause cellular toxicity. The cellular toxicity evaluated by MTS assay reveals that with 100 μM hexachlorophene, approximately 50% of the Vero E6 cells are still alive.

3.2. Inhibitor assay using a fluorogenic substrate

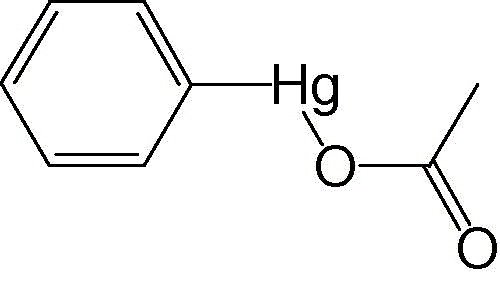

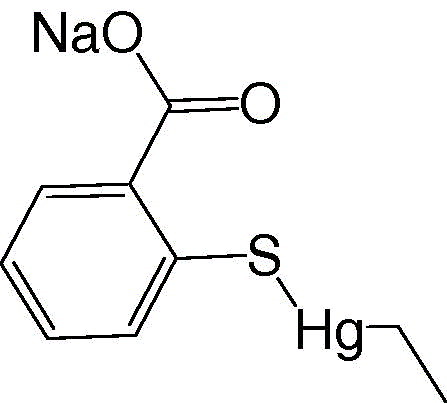

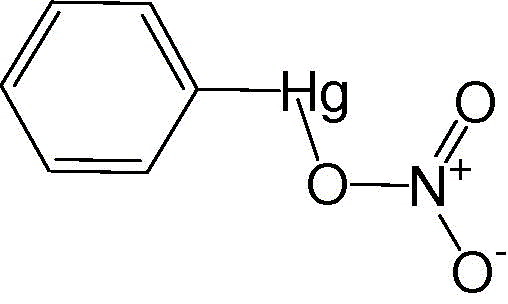

Determination of the K i values of phenylmercuric acetate, thimerosal, and hexachlorophene against 3CL protease indicated that these compounds were competitive inhibitors with K i values of 0.7 μM (phenylmercuric acetate), 2.4 μM (thimerosal), and 13.7 μM (hexachlorophene). Since mercury‐containing compounds such as phenylmercuric acetate and thimerosal may pose therapeutic hazards to a patient, we further evaluated a series of metal‐containing compounds (Table 1 ) and metal ions (Table 2 ). Paramount among these was a Zn‐conjugated compound.

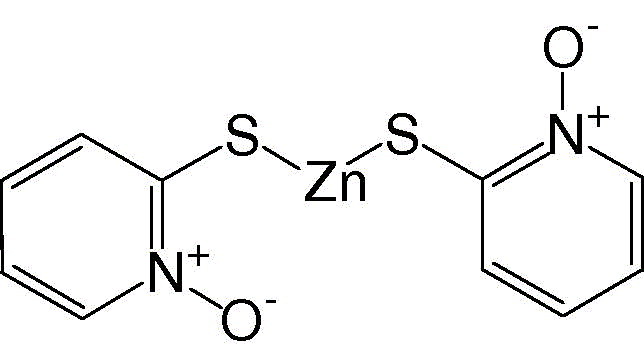

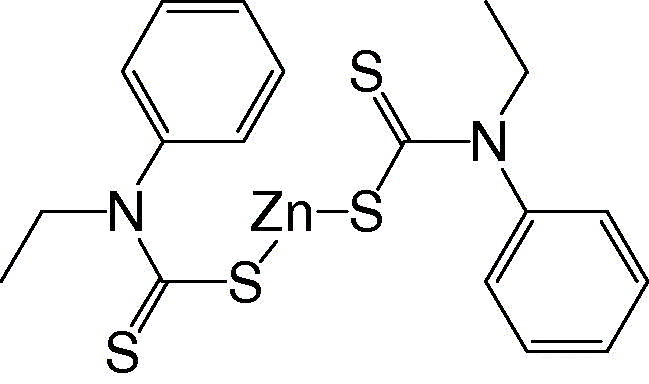

Table Table 1.

K i values and the structures of some inhibiotrs of SARS‐CoV 3CL protease

| Inhibitor | K i (μM) |

|---|---|

Phenylmercuric acetate

a

|

0.7 ± 0.3 |

Thimerosal

a

|

2.4 ± 0.2 |

Hexachlorophene

a

|

13.7 ± 0.4 |

Phenylmercuric nitrate

|

0.3 ± 0.3 |

1‐Hydroxypyridine‐2‐thione zinc

|

0.17 ± 0.07 |

N‐Ethyl‐N‐phenyldithiocarbamic acid zinc

|

1.0 ± 0.1 |

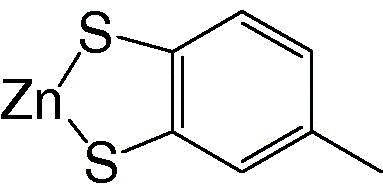

Toluene‐3,4‐dithiolato zinc

|

1.4 ± 0.2 |

Hits from 960‐compound library.

Table Table 2.

K i values of three metal ions in inhibiting the SARS‐CoV 3CL protease

| Metal ion | K i (μM) |

|---|---|

| Hg2+ | 0.5 ± 0.1 |

| Zn2+ | 1.1 ± 0.4 |

| Cu2+ | 4.9 ± 1.3 |

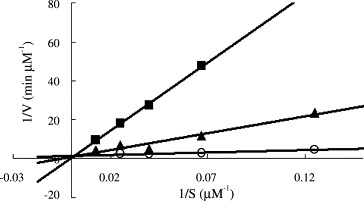

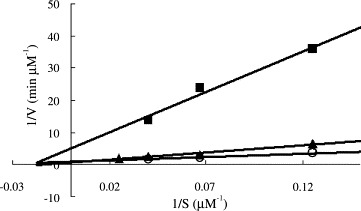

As shown in Fig. 3 , 1‐hydroxypyridine‐2‐thione zinc was a competitive inhibitor with a K i value of 0.17 μM. In contrast, Zn2+ acted non‐competitively against SARS‐CoV protease, with a 6‐fold larger K i value of 1.1 μM (Fig. 4 ). The indicated involvement of the organic moiety of the compound in inhibitory activity was supported by observations that N‐ethyl‐N‐phenyldithiocarbamic acid zinc and toluene‐3,4‐dithiolato zinc showed similar K i values (1.0 and 1.4 μM, respectively) to that of the Zn2+ (1.1 μM), whereas 1‐hydroxypyridine‐2‐thione zinc had a markedly smaller K i of 0.17 μM.

Figure 3.

The K i measurements of a selected SARS protease inhibitor 1‐hydroxypyridine‐2‐thione zinc. The enzyme activities were measured using 8–80 μM fluorogenic substrate in the absence (∘) or presence of 2 (▴) and 5 μM (■) inhibitor. The data were fitted with Eq. (1) using KinetAsyst II program to obtain the K i value (0.17 μM). The inhibition pattern indicates that 1‐hydroxypyridine‐2‐thione zinc is competitive with respect to the substrate.

Figure 4.

The K i measurements for zinc ion. The reaction velocities of SARS 3CL protease in the absence (∘) or presence of 3 (▴) and 5 μM (■) Zn2+ and various substrate concentrations ranged from 8 to 80 μM were used to determine the K i value (1.1 μM) of Zn2+ by fitting the data with Eq. (2) using KinetAsyst II program. The inhibition pattern indicates that zinc ion is non‐competitive with respect to the substrate.

3.3. Activity of niclosamide

Niclosamide, which is used in the treatment of parasitic disorders, shows promise as an inhibitor of SARS‐CoV replication [19]. It was then suggested to be a SARS‐CoV protease inhibitor on the basis of computer modeling [9]. However, presently, fluorimetric assay results were not indicative of any inhibitory effect of niclosamide against the protease (data not shown).

4. Discussion

In the present study, 960 commerically available drugs and biologically active substances, as well as metal‐conjugated compounds, were tested for their ability to functionally disrupt SARS‐CoV protease activity. The 3CL protease we prepared is dimeric in its functional form and is more active than the previously prepared 3CL protease [5, 11], by virtue of the absence of extra amino acids at the N‐ and C‐termini. Not only did the present study involve a more potent enzyme, but the enzyme activity was assessed in real‐time using a fluorogenic substrate [12]. These examinations have identified protease inhibition by some of the compounds tested. These effective compounds also suppress viral replication, correlative with their anti‐SARS‐CoV protease activity.

Two of these compounds, phenylmercuric acetate and thimerosal, are used as pharmaceutical excipients, and are widely used as antimicrobial preservatives in parenteral and topical pharmaceutical formulations [20]. In particular, phenylmercuric acetate is used as an antimocrobial preservative in cosmetics, as a bactericide in parenterals and eye‐drops, and as a spermicide. Another effective compound, hexachlorophene, is an antibacterial compound that is a common constituent of soaps and scrubs and is experimentally used as a cholinesterase inhibitor.

In addition to the anti‐viral activity of these commercially available compounds, several metallic species displayed potential against the SARS‐CoV protease. Several metal ions inhibit Cys protease via the interaction with a nucleophilic sulfur anion [14]. SARS‐CoV 3CL protease is also a Cys protease. Presently, seven transition metal ions were tested. While Hg2+, Zn2+ and Cu2+ were effective, Co2+, Mg2+, Mn2+, and Ni2+ did not inhibit 3CL protease activity. These metal ions are non‐competitive inhibitors by virtue of their size. They are too small to block substrate binding, despite being capable of interaction with the active site Cys residue. Phenylmercuric acetate and phenylmercuric nitrate are similar to Hg2+ in their inhibitory power. However, the observed markedly higher affinity of 1‐hydroxypyridine‐2‐thione zinc for the protease, compared to Zn2+, is consistent with the suggestion that the former is a more specific 3CL inhibitor. It is noteworthy that Zn‐containing compounds such as zinc acetate are added as a supplement to the drug for the treatment of Wilson's disease [21], indicating the safety of the ion for human use. More relevantly, zinc salts such as zincum gluconicum (Zenullose) may be effective in treating the common cold, a disease caused by rhinoviruses, without knowledge of the molecular target [22]. Thus, the present documentation of the anti‐SARS, sub‐micromolar K i action of Zn‐conjugated compounds provides a firm foundation on which to embark upon SARS therapeutic drug explorations.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a grant from National Science Council NSC92‐2751‐B‐001‐012‐Y to P.H.L. and NSC92‐2751‐B‐400‐006‐Y to X.C. and J.T.A.H.

Hsu John T.-A.,Kuo Chih-Jung,Hsieh Hsing-Pang,Wang Yeau-Ching,Huang Kuo-Kuei,Lin Coney P.-C.,Huang Ping-Fang,Chen Xin and Liang Po-Huang(2004), Evaluation of metal-conjugated compounds as inhibitors of 3CL protease of SARS-CoV, FEBS Letters, 574, doi: 10.1016/j.febslet.2004.08.015

References

- 1. Drosten C., Gunther S., Preiser W., van der Werf S., Brodt H.R., Becker S., Rabenau H., Panning M., Kolesnikova L., Fouchier R.A., N. Eng. J. Med., 348, (2003), 1967– 1976. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Fouchier R.A., Kuiken T., Schutten M., van Amerongen G., van Doornum G.J., van den Hoogen B.G., Peiris M., Lim W., Stohr K., Osterhaus A.D., Nature, 423, (2003), 240– [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Ksiazek T.G., Erdman D., Goldsmith C.S., Zaki S.R., Peret T., Emery S., Tong S., Urbani C., Comer J.A., Lim W., N. Eng. J. Med., 348, (2003), 1953– 1966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Peiris J.S., Lai S.T., Poon L.L., Guan Y., Yam L.Y., Lim W., Nicholls J., Yee W.K., Yan W.W., Cheung M.T., Cheng V.C., Chan K.H., Tsang D.N., Yung R.W., Ng T.K., Yuen K.Y., Lancet, 361, (2003), 1319– 1325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Fan K., Wei P., Feng Q., Chen S., Huang C., Ma L., Lai B., Pei J., Liu Y., Chen J., Lai L., J. Biol. Chem., 279, (2004), 1637– 1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Anand K., Palm G.J., Mesters J.R., Siddell S.G., Ziebuhr J., Hilgenfeld R., EMBO J., 21, (2002), 3213– 3224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Anand K., Ziebuhr J., Wadhwani P., Mesters J.R., Hilgenfeld R., Science, 300, (2003), 1763– 1767. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Yang H., Yang M., Ding Y., Liu Y., Lou Z., Zhou Z., Sun L., Mo L., Ye S., Pang H., Gao G.F., Anand K., Bartlam M., Hilgenfeld R., Rao Z., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 100, (2003), 13190– 13195. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Zhang X.W., Yap Y.L., Bioorgan. Med. Chem., 12, (2004), 2517– 2521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Jenwitheesuk E., Samudrala R., Bioorgan. Med. Chem. Lett., 13, (2003), 3989– 3992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Bacha U., Barrila J., Velazquez-Campoy A., Leavitt S.A., Freire E., Biochemistry, 43, (2004), 4906– 4912. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Kuo C.J., Chi Y.H., Hsu J.T.-A., Liang P.H., Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun., 318, (2004), 862– 867. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Wu C.Y., Jan J.T., Ma S.H., Kuo C.J., Juan H.F., Cheng Y.S., Hsu H.H., Huang H.C., Wu D., Brik A., Liang F.S., Liu R.S., Fang J.M., Chen S.T., Liang P.H., Wong C.H., Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA, 101, (2004), 10012– 10017. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Basak A., Toure B.B., Lazure C., Mbikay M., Chretien M., Seidah N.G., Biochem. J., 343, (1999), 29– 37. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Korant B.D., Kauer J.C., Butterworth B.E., Nature, 248, (1974), 588– 590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Merluzzi V.J., Cipriano D., McNeil D., Fuchs V., Supeau C., Rosenthal A.S., Skiles J.W., Res. Commun. Chem. Pathol. Pharmacol., 66, (1989), 425– 440. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wu H.S., Hsieh Y.C., Su I.J., Lin T.H., Chiu S.C., Hsu Y.F., Lin J.H., Wang M.C., Chen J.Y., Hsiao P.W., Chang G.D., Wang A.H.-J., Ting H.W., Chou C.M., Huang C.J., J. Biomed. Sci., 11, (2004), 117– 126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Cory A.H., Owen T.C., Barltrop J.A., Cory J.G., Cancer Commun., 3, (1991), 207– 212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wu C.J., Jan J.T., Chen C.M., Hsieh H.P., Hwang D.R., Liu H.W., Liu C.Y., Huang H.W., Chen S.C., Hong C.F., Lin R.K., Chao Y.S., Hsu J.T.A., Antimicrobial. Agents Chemother., 48, (2004), 2693– 2696. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Rowe R.C., Sheskey P.J., Weller P.J., Handook of Pharmaceutical Excipients. 4th Edn. (2003), Pharmaceutical Press ; [Google Scholar]

- 21. Brewer G.J., Johnson V.D., Dick R.D., Hedera P., Fink J.K., Kluin K.J., Hepatology, 31, (2000), 364– 370. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Mossad S.B., Q. J. Med., 96, (2003), 35– 43. [Google Scholar]