Abstract

SARS main protease is essential for life cycle of SARS coronavirus and may be a key target for developing anti-SARS drugs. Recently, the enzyme expressed in Escherichia coli was characterized using a HPLC assay to monitor the formation of products from 11 peptide substrates covering the cleavage sites found in the SARS viral genome. This protease easily dissociated into inactive monomer and the deduced Kd of the dimer was 100 μM. In order to detect enzyme activity, the assay needed to be performed at micromolar enzyme concentration. This makes finding the tight inhibitor (nanomolar range IC50) impossible. In this study, we prepared a peptide with fluorescence quenching pair (Dabcyl and Edans) at both ends of a peptide substrate and used this fluorogenic peptide substrate to characterize SARS main protease and screen inhibitors. The fluorogenic peptide gave extremely sensitive signal upon cleavage catalyzed by the protease. Using this substrate, the protease exhibits a significantly higher activity (kcat=1.9 s−1 and Km=17 μM) compared to the previously reported parameters. Under our assay condition, the enzyme stays as an active dimer without dissociating into monomer and reveals a small Kd value (15 nM). This enzyme in conjunction with fluorogenic peptide substrate provides us a suitable tool for identifying potent inhibitors of SARS protease.

Keywords: SARS protease, Chymotrypsin, Cysteine protease, Fluorescence resonance energy transfer, Fluorogenic substrate, Inhibitor screening

Beginning in late 2002, approximately a thousand cases had been reported for patients mostly in China, Hong-Kong, Taiwan, and Canada, who showed the severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) and died due to the infection by human coronavirus [1], [2], [3], [4]. Since then, much effort has been devoted in sequencing the whole genome of the virus [5], [6], studying the origin of the virus by comparative genetics [7], [8], solving the crystal structure of the essential main protease and performing computer modeling for structure-based design of its inhibitors [9], [10], [11], and examining the mechanism of viral infection to identify the human receptor angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 for viral attachment [12], [13], [14]. The main protease which is responsible for maturation of polyproteins in the life cycle of the virus has been proposed as a key target for development of anti-SARS drug [9], [10], [11]. This protein is a chymotrypsin-like protease but uses a Cys rather than a Ser as the nucleophile in the active site, so it is also called chymotrypsin-like or 3C-like protease.

The main protease had been cloned and overexpressed by using Escherichia coli as a host for characterization, which contained the hexa-His tag in its C-terminus [15]. From this previous study, the enzyme existed as a mixture of monomer and dimer at 4 mg/mL (∼118 μM) protein concentration and exclusively monomer at lower protein concentration 0.2 mg/mL (∼6 μM) as revealed by analytical gel filtration. The deduced dissociation constant K d of the dimer was estimated to be 100 μM. It was concluded that only the dimer is active from the plot of the kinetic parameter k cat/K m versus the enzyme concentration [15]. The substrate specificity of the protease was established by measuring the kinetic parameters of the enzyme for the 11 peptides which are 11-amino acid long with sequences found as possible cleavage sites for the protease in the SARS genome. The best substrate TSAVLQSGFRK-NH2 displayed a k cat/K m=10.6 mM−1 min−1 (k cat=12.2 min−1 and K m=1.15 mM). These kinetic assays were performed using HPLC to monitor the cleavage of the peptide substrate into two product fragments. Due to the poor enzyme activity, the assay needed to be performed at micromolar enzyme concentration. It is impossible to obtain the tight-binding inhibitors with IC50 at nanomolar range using this assay format.

In this study, we have developed a 12-amino acid peptide substrate (TSAVLQSGFRKM) plus Lys and Glu for attachment of 4-(4-dimethylaminophenylazo)benzoic acid (Dabcyl) and 5-[(2-aminoethyl)amino]naphthalene-1-sulfonic acid (Edans) in N- and C-termini, respectively. The two fluorophores form a quenching pair and exhibit fluorescence resonance energy transfer (FRET) within the peptide [16], [17]. When the peptide is cleaved by the SARS main protease, the FRET disappears and the fluorescence increases. By monitoring the increase of the fluorescence, the enzyme activity can be detected at sub-nanomolar protein concentration with sufficient sensitivity. The screening for the nanomolar IC50 inhibitors thus can be performed at the very low enzyme concentration. This assay using fluorescence plate reader also offers the advantage of higher throughput over the HPLC assay.

Materials and methods

Materials. Fluorogenic peptide substrate Dabcyl-KTSAVLQSGFRKME-Edans was prepared by Biogenesis (Taiwan). The peptide was purified to a single peak by using HPLC. The plasmid mini-prep kit, DNA gel extraction kit, and Ni–NTA resin were purchased from Qiagen. FXa and the protein expression kit (including the pET32Xa/LIC vector and competent JM109 and BL21 cells) were obtained from Novagen. DTT was purchased from Pierce. 1-Hydroxypyridine-2-thione zinc was purchased from Sigma. All commercial buffers and reagents were of the highest grade.

Expression and purification of SARS main protease. The gene encoding SARS main protease was cloned from viral whole genome obtained from National Taiwan University [8] by using polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and the primers (forward primer 5′-GGTATTGAGGGTCGCAGTGGTTTTAGG-3′ and reverse primer 5′-AGAGGAGAGTTAGAGCCTTATTGGAAGGTAACACC-3′) into the pET32Xa/Lic vector using the same strategy as previously reported [18]. The recombinant protease plasmid was then used to transform E. coli JM109 competent cells that were streaked on a Luria–Bertani (LB) agar plate containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin. Ampicillin-resistant colonies were selected from the agar plate and grown in 5 mL LB culture containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin overnight at 37 °C. The correct construct was subsequently transformed to E. coli BL21 for protein expression. The 5-mL overnight culture of a single transformant was used to inoculate 500 mL of fresh LB medium containing 100 μg/mL ampicillin. The cells were grown to A 600=0.6 and induced with 1 mM isopropyl-β-thiogalactopyranoside. After 4–5 h, the cells were harvested by centrifugation at 7000g for 15 min.

The enzyme purification was conducted at 4 °C. The cell paste obtained from 2-L cell culture was suspended in 80 mL lysis buffer containing 12 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 120 mM NaCl, and 0.1 mM EDTA in the presence of 7.5 mM β-ME, 1 mM DTT plus 7.5 mM β-ME, 2 mM DTT, or 17.5 mM β-ME. French-press instrument (AIM-AMINCO spectronic Instruments) was used to disrupt the cells at 12,000 psi. The lysis solution was centrifuged and the debris was discarded. The cell free extract was loaded onto a 20 mL Ni–NTA column which was equilibrated with 12 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 120 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 5 mM imidazole containing different combinations of reducing agents (7.5 mM β-ME, 7.5 mM β-ME plus 1 mM DTT, 17.5 mM β-ME, or 2 mM DTT). The column was washed with 5 mM imidazole followed by 30 mM imidazole-containing buffer. His-tagged protease was eluted with 12 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 120 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 300 mM imidazole containing the aforementioned reducing agents. The protein solution was dialyzed against 2 × 2 L buffer (12 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 120 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and the reducing agents).

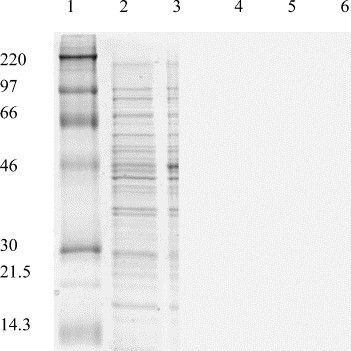

His-tagged protease was then digested with FXa protease to remove the tag and the mixture was loaded onto Ni–NTA. The untagged protease in flowthrough (12 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 120 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 5 mM imidazole containing the reducing agents) was highly pure according to SDS–PAGE (Fig. 1 ) and was dialyzed to buffer (12 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 120 mM NaCl, and 0.1 mM EDTA with reducing agents) for storage. The purified protein was confirmed by N-terminal sequencing and mass spectrometry. The enzyme concentration used in all experiments was determined from the absorbance at 280 nm.

Fig. 1.

SDS–PAGE analysis of the SARS main protease at different stages of purification procedure. Lane 1 represents the molecular mass markers which are 220, 97, 66, 46, 30, 21.5, and 14.3 kDa. Lanes 2 and 3 show the cell lysate without and with IPTG induction to overexpress SARS main protease with tag, respectively. Lane 4 is the tagged protease after Ni–NTA column chromatography. Lane 5 represents the protease treated with FXa to remove the tag. Two extra bands, intact protease and the tag at lower molecular mass, appear on SDS–PAGE. Lane 6 shows the purified untagged protease after using the second Ni–NTA column.

Activity assay of the protease using the fluorogenic substrate. The kinetic measurements were performed in 20 mM Bis–Tris (pH 7.0) at 25 °C. Enhanced fluorescence due to cleavage of the fluorogenic substrate peptide (Dabcyl-KTSAVLQSGFRKME-Edans) was monitored at 538 nm with excitation at 355 nm using a fluorescence plate reader (Fluoroskan Ascent from ThermoLabsystems, Sweden). The enzyme concentration used in measuring K m and k cat values was 50 nM and the substrate concentrations from 0.5- to 5-fold K m value were used. Substrate concentration was determined by using the extinction coefficients 5438 M−1 cm−1 at 336 nm (Edans) and 15,100 M−1 cm−1 at 472 nm (Dabcyl). The initial rate within 10% substrate consumption was used to calculate the kinetic parameters using Michaelis–Menten equation fitting by the KaleidaGraph computer program.

Enzyme concentration ranges of 5–150 or 50–3000 nM with 60 μM fluorogenic substrate were used to determine the apparent dimer–monomer dissociation constant K d. The K d values were obtained by fitting the plot of reaction rates versus enzyme concentration to the following equations assuming the dimer is active and the monomer is inactive [19].

| Kd=[M]2/[D], | (1) |

| [D]=1/8[Kd+4[E]t−sqrt(Kd2+8Kd[E]t)], | (2) |

| v=As{1/8[Kd+4[E]t−sqrt(Kd2+8Kd[E]t)]}. | (3) |

In these equations, [D] is the dimer concentration, [M] is the monomer concentration, the total enzyme concentration [E]t=[M]+2[D], v is the observed reaction rate, and As is the activity of dimer.

Gel filtration determination of protein form. The molecular species of the SARS protease was determined on a pre-packed Sephadex G-200 column (1 cm × 20 cm, Amersham–Pharmacia Biotech) by comparing the elution volume of the protease with those of protein molecular mass standards including aldolase (170 kDa), bovine serum albumin (67 kDa), ovalbumin (43 kDa), and chymotrypsinogen A (25 kDa). The same buffer used in Ni–NTA column was used to elute the proteins at a flow rate of 0.5 mL/min.

Inhibition assay. The IC50 value of 1-hydroxypyridine-2-thione zinc was measured in a reaction mixture containing 50 nM SARS protease, 6 μM fluorogenic substrate in a buffer of 12 mM Tris–HCl, pH 7.5, 120 mM NaCl, 0.1 mM EDTA, and 1 mM DTT plus 7.5 mM β-ME in the presence of various concentrations of the inhibitor which ranged from 0 to 50 μM. The fluorescence change resulted from the reaction was followed with time using the 96-well fluorescence plate reader. The initial velocities of the inhibited reactions were plotted against the different inhibitor concentrations to obtain the IC50 by fitting with the following equation:

| A(I)=A(0)×{1−[I/(I+IC50)]}. | (4) |

In this equation, A(I) is the enzyme activity with inhibitor concentration I; A(0) is the enzyme activity without inhibitor; and I is the inhibitor concentration.

Results

Expression and purification of SARS main protease

SARS protease encoding gene was amplified using PCR method and inserted into commercial vector pET-32Xa/LIC for expression of the enzyme with thioredoxin, hexa-His tag, and FXa protease cleavage site on the N-terminus. The engineered plasmid in E. coli BL21 host cell under the control T7 promoter yielded large quantity of recombinant His-tagged SARS protease. The Ni–NTA column was employed for the His-tagged protease purification. After the tag cleavage by FXa protease, the mixture was loaded onto another Ni–NTA. The flowthrough thus contained highly pure untagged protease as shown by reducing SDS–PAGE (Fig. 1). Unlike the previously prepared SARS protease, which contains the C-terminal hexa-His tag, our SARS protease is intact without any tag. The final recovery yield for purified protein was approximately 50 mg/L culture, which is about 3- to 5-fold higher than 10 or 15 mg/L obtained by using the pET21a or PQE30 vector as described previously [15], [18].

Effect of reducing agents on enzyme activity

It is notable that the inclusion of β-ME or DTT with sufficient reducing power is required to obtain highly active protease. With only 7.5 mM β-ME presence during the purification, the enzyme activity was 3-fold lower. Addition of 2 mM DTT, 7.5 mM β-ME plus 1 mM DTT, or 17.5 mM β-ME during the purification was found sufficient to produce highly active enzyme with the Km=17±4 μM and the k cat=1.9±0.1 s−1 (see below). These values are significantly higher than reported values obtained from the SARS protease that contained C-terminal hexa-His tag and was purified under 7.5 mM β-ME [15].

Kinetic and equilibrium constants of the protease

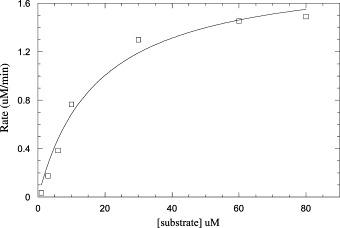

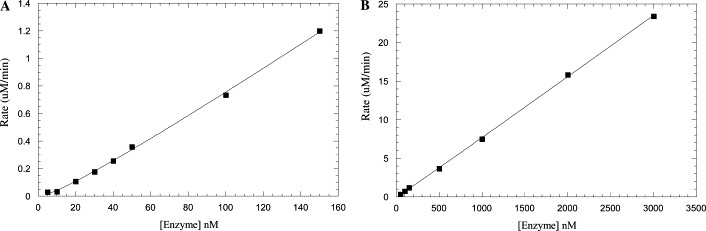

The peptide cleavage reaction of SARS main protease can be easily monitored in real time by using the fluorescence plate reader. For the fluorogenic substrate Dabcyl-KTSAVLQSGFRKME-Edans, the K m value was measured to be 17 ± 4 μM and the k cat value was 1.9 ± 0.1 s−1 (Fig. 2 ). The enzyme prepared and assayed under our conditions shows 9-fold larger k cat and 68-fold smaller K m values than the previously reported values of 12.2 min−1 and 1.15 mM, respectively [15]. By measuring the activity versus enzyme concentration as shown in Fig. 3A , the apparent K d value for the dimer–monomer equilibrium of our enzyme was measured to be 15 ± 4 nM. This is based on the same assumption that the dimer is active and monomer contains no enzyme activity as proposed previously [15]. At protein concentration 50–3000 nM (significantly larger than the K d value), the fitting curve is almost linear (Fig. 3B). Thus, the K d (15 nM) is 6.7 × 103 times smaller than that (100 μM) previously estimated from analytical gel filtration experiments [15]. The k cat/K m of protease with respect to the fluorogenic substrate Dabcyl-KTSAVLQSGFRKME-Edans is 0.11 μM−1 s−1, approximately 600 times larger than previously determined 10.6 mM−1 min−1 (=1.8 × 10−4 μM−1 s−1) using shorter and unlabeled TSAVLQSGFRK substrate and HPLC assay. However, by considering the K d (100 μM) assigned for the previous enzyme [15], the catalytic efficiency k cat/K m=1.4×103 mM−1 min−1 of that dimer is only about 4-fold smaller than our measured value.

Fig. 2.

Measurements of kinetic parameters of SARS main protease. The reaction initial rates of the protease under a variety of different substrate concentrations were plots against substrate concentrations to obtain the Vmax and Km values of the enzyme. KaledaGraph computer program was used to fit the kinetic data using Michaelis–Menten equation.

Fig. 3.

Dependence of SARS protease reaction rate on enzyme concentration. The 5–150 nM SARS main protease as shown in (A) and 50–3000 nM as shown in (B) with 60 μM fluorogenic substrate were used to determine the Kd value of dimer–monomer equilibrium. From (A), the Kd was determined to be 15 ± 4 nM by fitting the data to Eq. (3) (see Materials and methods). At the protein concentrations from 50 to 3000 nM (significantly larger than the Kd value), the fitting curve is almost linear.

Gel filtration experiments

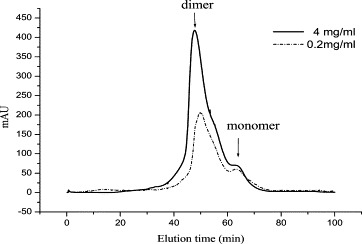

To see whether the SARS protease prepared in our hand stays as an active dimer with K d (15 nM) remarkably smaller than the previous value (100 μM), we have used gel filtration to monitor the form (dimer versus monomer) of the protease at the same concentrations used previously [15]. As shown in Fig. 4 , at the 0.2 mg/mL protein concentration, our SARS main protease shows a major peak corresponding to the dimer form. Under the same concentration of SARS protease, previous report showed that the enzyme was a monomer exclusively. At 4 mg/mL of our SARS protease, dimer was also found (Fig. 4) but previous enzyme displayed a mixture of monomer and dimer in this case. However, formation of a small shoulder (<5% of the total absorbance) at the position of monomer may be due to the partial dilution of the protein during the elution in the column or other impurity. Compared to previous protease, the SARS protease prepared by us shows greater tendency to form dimer, consistent with the much smaller K d value.

Fig. 4.

Gel filtration study of the SARS protease. At 0.2 (dot-and-dash line) and 4 mg/mL (solid line), the SARS protease shows a major peak corresponding to the dimer on the elution profile of gel filtration column chromatography. The arrows indicate the positions for dimer and monomer of the protease.

Use of the fluorogenic substrate to assay protease inhibitors

The highly active enzyme in conjunction with the sensitive fluorometric assay enables us to perform inhibitor screening using nanomolar SARS protease. Screening from a panel of compounds, we found that 1-hydroxypyridine-2-thione zinc exhibited 0.8 μM IC50 toward SARS protease by using this assay method. The zinc ion itself at this concentration does not inhibit the protease, indicating the specificity of the compound against the SARS protease. This assay was completed in a short period of time (10 min) using a 96-well fluorescence plate reader.

Discussion

In this study, we have prepared the SARS main protease with higher yield and activity compared to the previous one [15]. The enzyme activity is dependent upon the concentration of reducing agents used. The inclusion of 1 mM DTT in addition to 7.5 mM β-ME (or 2 mM DTT or 17.5 mM β-ME) is sufficient for optimal enzyme activity. Addition of excess DTT (10 mM) did not further increase the protease activity in our assay (data not shown). Since the enzyme is a chymotrypsin-like protease but uses Cys as the nucleophile to attack its substrate, the inclusion of the extra reducing agents may help to maintain the free thiol form of the active site Cys residue. However, it may also protect the correct protein conformation by preventing the formation of the incorrect disulfide bond in the enzyme. Indeed, the main protease contains 12 Cys residues, totally reduced without forming any disulfide linkage as revealed by its crystal structure [10]. The enzyme was prepared with 1 mM DTT in that structural study. This indicates that the reducing power higher than that of 1 mM DTT may be sufficient to yield fully active enzyme.

The possible causes of more active SARS protease (mainly dimeric) compared to the previous one may be due to the use of the different fluorogenic substrates and the absence of any tag on our protein. The substrate we used contains Dabcyl and Edans FRET pair and the 12 amino acids of the protease’s preferred cleavage site plus two amino acids for linking with the fluorophores, which may increase the affinity (smaller K m value) of the substrate to the enzyme. The previously used peptide substrate only contains 11 amino acids (six in P and five in P′ positions). The hexa-His tag attached to C-terminus of the enzyme may also interfere with the enzyme activity (Chang et al., unpublished observation). The inclusion of anti-chaotropic agents (10% glycerol and 0.5 M Na2SO4) as used previously to promote dimer formation in human cytomegalovirus virus [20] in our buffer did not further increase the SARS protease activity since the protease already existed as a dimer under assay condition. The analytical ultracentrifugation measurements of the K d of the protease in solution also support our finding (Chang et al., personal communication).

As demonstrated in this study, our method of using fluorogenic substrate and fluorescence plate reader appears to be a convenient and suitable one for inhibitor assay. The protease prepared and assayed by us shows only 4-fold larger k cat/K m value for the active dimer but remarkably smaller K d of the dimer compared to the previously prepared enzyme [15]. From the 3-D structure of SARS protease, the N-terminus of one subunit makes close contact with the active site of the other subunit. The importance of the N-finger and dimerization is supported by the fact that a deletion mutant of the related TGEV main protease that lacks residues 1–5 is almost completely inactive [21]. However, the importance of the C-terminus in dimerization for 3CL protease has not been reported until now. In our solved X-ray structure of SARS protease (Wang et al., unpublished results), the C-terminus is indeed very close to the N-terminus. The distance between Phe3Cα and Ser301Cα is 11.5 Å (we cannot detect the electron density of first 2 amino acids in N-terminus and the last 5 amino acids in C-terminus). His-tag in the C-terminus may interfere with the dimer formation. Using our assay method with active enzyme and fluorogenic substrate, we have shown a sub-micromolar inhibitor as an example and other inhibitors will be reported elsewhere in detail. This sensitive method can be used in finding tight-binding inhibitors of nanomolar and smaller IC50 for SARS protease as leads for anti-SARS drug discovery.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a grant from National Science Council NSC92-2751-B-001-012-Y to P.H.L. Authors thank the technical assistance of Mr. Kuo-Kuei Huang. We also appreciate the unpublished data provided by Dr. Andrew H.-J. Wang and Dr. Gu-Gang Chang. We gratefully acknowledge the gifts of SARS viral cDNAs from National Taiwan University SARS team and Dr. Shin-Ru Shih at Chang-Gung University.

Footnotes

Abbreviations: SARS, severe acute respiratory syndrome; Dabcyl, 4-(4-dimethylaminophenylazo)benzoic acid; Edans, 5-[(2-aminoethyl)amino]naphthalene-1-sulfonic acid; FRET, fluorescence resonance energy transfer; PCR, polymerase chain reaction; Ni–NTA, nickel–nitrilotriacetic acid; Tris, tris(hydroxymethyl)aminomethane; EDTA, ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid; SDS–PAGE, sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, β-ME, β-mercaptoethanol; DTT, dithiothreitol; sqrt, square root.

References

- 1.Drosten C., Gunther S., Preiser W., van der Werf S., Brodt H.R., Becker S., Rabenau H., Panning M., Kolesnikova L., Fouchier R.A., Berger A., Burguiere A.M., Cinatl J., Eickmann M., Escriou N., Grywna K., Kramme S., Manuguerra J.C., Muller S., Rickerts V., Sturmer M., Vieth S., Klenk H.D., Osterhaus A.D., Schmitz H., Doerr H.W. Identification of a novel coronavirus in patients with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1967–1976. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ksiazek T.G., Erdman D., Golsmith C.S., Zaki S.R., Peret T., Emery S., Tong S., Urbani C., Comer J.A., Lim W., Rollin P.E., Dowell S.F., Ling A.E., Humphrey C.D., Shieh W.J., Guarner J., Paddock C.D., Rota P., Fields B., DeRisis J., Yang J.Y., Cox N., Hughes J.M., LeDue J.W., Bellini W.J., Anderson L.J.A. A novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. N. Engl. J. Med. 2003;348:1953–1966. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa030781. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Fouchier R.A., Kuiken T., Schutten M., van Amerongen G., van Doornum G.J., van den Hoogen B.G., Peiris M., Lim W., Stohr K., Osterhaus A.D. Aetiology: Koch’s postulates fulfilled for SARS virus. Nature. 2003;423:240. doi: 10.1038/423240a. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Peiris J.S., Lai S.T., Poon L.L., Guan Y., Yam L.Y., Lim W., Nicholls J., Yee W.K., Yan W.W., Cheung M.T., Cheng V.C., Chan K.H., Tsang D.N., Yung R.W., Ng T.K., Yuen K.Y. Coronavirus as a possible cause of severe acute respiratory syndrome. Lancet. 2003;361:1319–1325. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13077-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Rota P.A., Oberste M.S., Monroe S.S., Nix W.A., Campagnoli R., Icenogle J.P., Penaranda S., Bankamp B., Maher K., Chen M.-H., Tong S., Tamin A., Lowe L., Frace M., Derisi J.L., Chen Q., Wang D., Erdman D.D., Peret T.C.T., Burns C., Ksiazek T.G., Rollin P.E., Sanchez A., Liffick S., Holloway B., Limor J., McCaustland K., Olsen-Rasmussen M., Fouchier R., Gunther S., Osterhaus A.D.M.E., Drosten C., Pallansch M.A., Anderson L.J., Bellini W.J. Characterization of a novel coronavirus associated with severe acute respiratory syndrome. Science. 2003;300:1394–1399. doi: 10.1126/science.1085952. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Marra M.A., Jones S.J.M., Astell C.R., Holt R.A., Brooks-Wilson A., Butterfield Y.S.N., Khattra J., Asano J.K., Barber S.A., Chan S.Y., Cloutier A., Coughlin S.M., Freeman D., Girn N., Griffith O.L., Leach S.R., Mayo M., McDonald H., Montgomery S.B., Pandoh P.K., Petrescu A.S., Robertson G., Schein J.E., Siddiqui A., Smailus D.E., Stott J.M., Yang G.S., Plummer F., Andonov A., Artsob H., Bastien N., Bernard K., Booth T.F., Bowness D., Czub M., Drebot M., Fernando L., Flick R., Garbutt M., Gray M., Grolla A., Jones S., Feldmann H., Meyers A., Kabani A., Li Y., Normand S., Stroher U., Tipples G.A., Tyler S., Vogrig R., Ward D., Watson B., Brunham R.C., Krajden M., Petric M., Skowronski D., Upton C., Roper R. The Genome sequence of the SARS-associated coronavirus. Science. 2003;300:1399–1404. doi: 10.1126/science.1085953. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ruan Y.J., Wei C.L., Ee A.L., Vega V.B., Thoreau H., Su S.T., Chia J.M., Ng P., Chiu K.P., Lim L., Zhang T., Peng C.K., Lin E.O., Lee N.M., Yee S.L., Ng L.F., Chee R.E., Stanto L.W., Long P.M., Liu E.T. Comparative full-length genome sequence analysis of 14 SARS coronavirus isolates and common mutations associated with putative origins of infection. Lancet. 2003;361:1779–1785. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(03)13414-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.S.H. Yeh, H.Y. Wang, C.Y. Tsai, C.L. Kao, J.Y. Yang, H.W. Liu, I.J. Su, S.F. Tsai, D.S. Chen, P.J. Chen, The National Taiwan University SARS Research Team, D.S. Chen, Y.T. Lee, C.M. Teng, P.C. Yang, H.N. Ho, P.J. Chen, M.F. Chang, J.T. Wang, S.C. Chang, C.L. Kao, W.K. Wang, C.H. Hsiao, P.R. Hsueh, Characterization of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus genomes in Taiwan: molecular epidemiology and genome evolution, Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 101 (2004) 2542–2547 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 9.Anand K., Ziebuhr J., Wadhwani P., Mesters J.R., Hilgenfeld R. Coronavirus main proteinase (3CLpro) structure: basis for design of anti-SARS drugs. Science. 2003;300:1763–1767. doi: 10.1126/science.1085658. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yang H., Yang M., Ding Y., Liu Y., Lou Z., Zhou Z., Sun L., Mo L., Ye S., Pang H., Gao G.F., Anand K., Bartlam M., Hilgenfeld R., Rao Z. The crystal structures of severe acute respiratory syndrome virus main protease and its complex with an inhibitor. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA. 2003;100:13190–13195. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1835675100. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chou K.C., Wei D.Q., Zhong W.Z. Binding mechanism of coronavirus main proteinase with ligands and its implication to drug design against SARS. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2003;308:148–151. doi: 10.1016/S0006-291X(03)01342-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li W.H., Moore M.J., Vasilieva N., Sui J., Wong S.K., Berne M.A., Somasundaran M., Sullivan J.L., Luzuriaga K., Greenough T.C., Choe H., Farzan M. Angiotensin-converting enzyme 2 is a functional receptor for the SARS coronavirus. Nature. 2003;426:450–454. doi: 10.1038/nature02145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Dales N.A., Gould A.E., Brown J.A., Calderwood E.F., Guan B., Minor C.A., Gavin J.M., Hales P., Kaushik V.K., Stewart M., Tummino P.J., Vickers C.S., Ocain T.D., Patane M.A. Substrate-based design of the first class of angiotensin-converting enzyme-related carboxypeptidase (ACE2) inhibitors. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 2002;124:11852–11853. doi: 10.1021/ja0277226. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang L., Sexton D.J., Skogerson K., Devlin M., Smith R., Sanyal I., Parry T., Kent R., Enright J., Wu Q., Conley G., DeOliveira D., Morganelli L., Ducar M., Wescott C.R., Ladner R.C. Novel peptide inhibitors of angiotensin-converting enzyme 2. J. Biol. Chem. 2003;278:15532–15540. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M212934200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fan K., Wei P., Feng Q., Chen S., Huang C., Ma L., Lai B., Pei J., Liu Y., Chen J., Lai L. Biosynthesis, purification, and substrate specificity of severe acute respiratory syndrome coronavirus 3C-like proteinase. J. Biol. Chem. 2004;279:1637–1642. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M310875200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Matayoshi E.D., Wang G.T., Krafft G.A., Erickson J. Novel fluorogenic substrates for assaying retroviral proteases by resonance energy transfer. Science. 1990;247:954–958. doi: 10.1126/science.2106161. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Liang P.H., Brun K.A., Field J.A., O’Donnell K., Doyle M.L., Green S.M., Baker A.E., Blackburn M.N., Abdel-Meguid S.S. Site-directed mutagenesis probing the catalytic role of arginines 165 and 166 of human cytomegalovirus protease. Biochemistry. 1998;37:5923–5929. doi: 10.1021/bi9726077. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen Y.H., Chen A.P.-C., Chen C.T., Wang A.H.-J., Liang P.H. Probing the conformational change of Escherichia coli undecaprenyl pyrophosphate synthase during catalysis using an inhibitor and tryptophan mutants. J. Biol. Chem. 2002;277:7369–7376. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110014200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun H., Luo H., Yu C., Sun T., Chen J., Peng S., Qin J., Shen J., Yang Y., Xie Y., Chen K., Wang Y., Shen X., Jiang H. Molecular cloning, expression, purification, and mass spectrometric characterization of 3C-like protease of SARS coronavirus. Protein Expr. Purif. 2004;32:302–308. doi: 10.1016/j.pep.2003.08.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Khayat R., Batra R., Bebernitz G.A., Olson M.W., Tong L. Characterization of the monomer–dimer equilibrium of human cytomegalovirus protease by kinetic methods. Biochemistry. 2004;43:316–322. doi: 10.1021/bi035170d. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Anand K., Palm G.J., Mesters J.R., Siddell S.G., Ziebuhr J., Hilgenfeld R. Structure of coronavirus main proteinase reveals combination of a chymotrypsin fold with an extra alpha-helical domain. EMBO J. 2002;21:3213–3224. doi: 10.1093/emboj/cdf327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]