Abstract

Under proteotoxic stress, some cells survive whereas others die. Mechanisms governing this heterogeneity in cell fate are unknown. We report that condensation and phase transition of heat-shock factor 1 (HSF1), a transcriptional regulator of chaperones1,2, is integral to cell fate decisions underlying survival or death. During stress, HSF1 drives chaperone expression but also accumulates separately in nuclear stress bodies (foci)3–6. Foci formation has been regarded as a marker of cells actively upregulating chaperones3,6–10. Using multiplexed tissue imaging, we observed HSF1 foci in human tumors. Paradoxically, their presence inversely correlated with chaperone expression. By live-cell microscopy and single-cell analysis, we found that foci dissolution rather than formation promoted HSF1 activity and cell survival. During prolonged stress, the biophysical properties of HSF1 foci changed; small, fluid condensates enlarged into indissoluble gel-like arrangements with immobilized HSF1. Chaperone gene induction was reduced in such cells, which were prone to apoptosis. Quantitative analysis suggests that survival under stress results from competition between concurrent yet opposing mechanisms. Foci may serve as sensors that tune cytoprotective responses, balancing rapid transient responses and irreversible outcomes.

Keywords: phase separation, multiplexed imaging, quantitative pathology, t-CyCIF, heat-shock response, HSP27, HSP70, heat shock factor 1, HSF1

When cells experience stress, HSF1 undergoes extensive phosphorylation, trimerizes, binds to heat-shock promoters and upregulates a transcriptional program consisting of chaperone genes11. This response increases protein folding capacity, rebalances protein homeostasis and supports cellular function12. The HSF1 nuclear stress bodies (foci)3–6 that also form in response to stress are dynamic structures that resolve as cells recover3,5,6. They do not form on HSP gene promoters but instead on DNA loci containing non-coding satellite III repetitive sequences5,6,13–16 and at pericentromeric regions17. While implicated in relocalization of splicing factors13, the functions of transcripts generated by satellite III and pericentromeric loci are not well understood. In bulk analyses, the formation of HSF1 foci correlates with a dramatic increase in chaperone gene transcription3,4,6,18. These observations have supported the prevailing view that the appearance of HSF1 foci is a sign of HSF1 activation6–9,18, consistent with the role for HSF1 in mediating cytoprotection. However, the connection between proteotoxic stress, formation of HSF1 foci and chaperone gene expression has not been subjected to rigorous single-cell analyses.

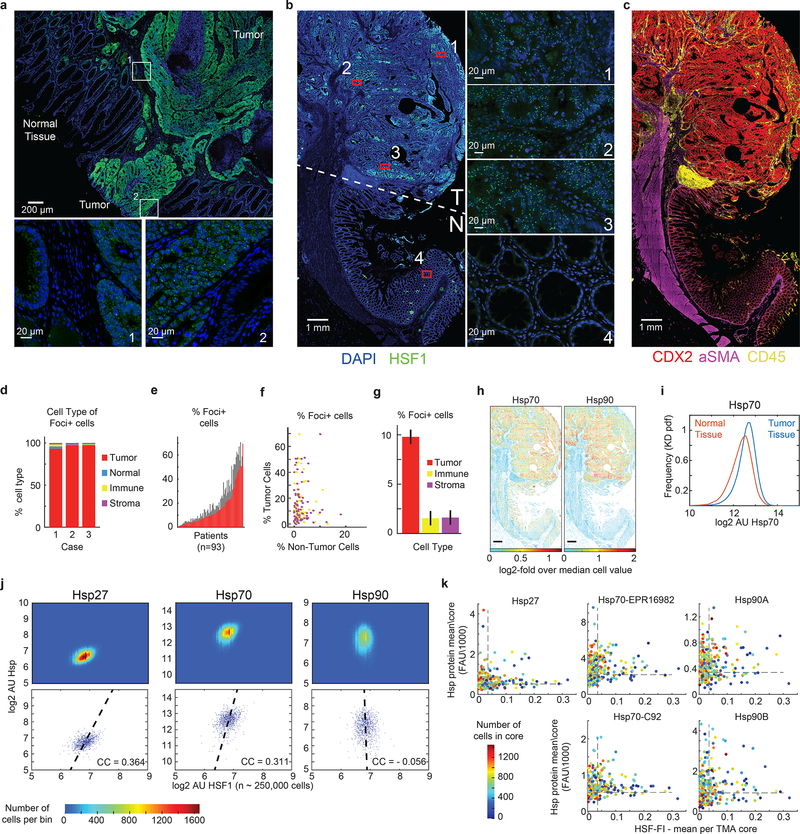

While examining surgical resections of human cancer using immunofluorescence microscopy, we observed that HSF1 localized to intranuclear foci in diverse cancers (Fig.1a; Extended-Data Fig.1a,b). Using multiplexed immunofluorescence imaging (t-CyCIF)19,20, we quantified the levels and localization of 10 stress-response proteins and lineage markers, including HSF1 and the HSP27, HSP70 and HSP90 chaperones. In both tissue and cultured cells, we quantified HSF1 localization to intranuclear foci using an “HSF1-Focus Index” (HSF1-FI); HSF1-FI ranges between 0 and 1 and represents the ratio between the amount of HSF1 signal measured within foci in individual nuclei relative to the total amount of nuclear HSF1 detected within the same cell.

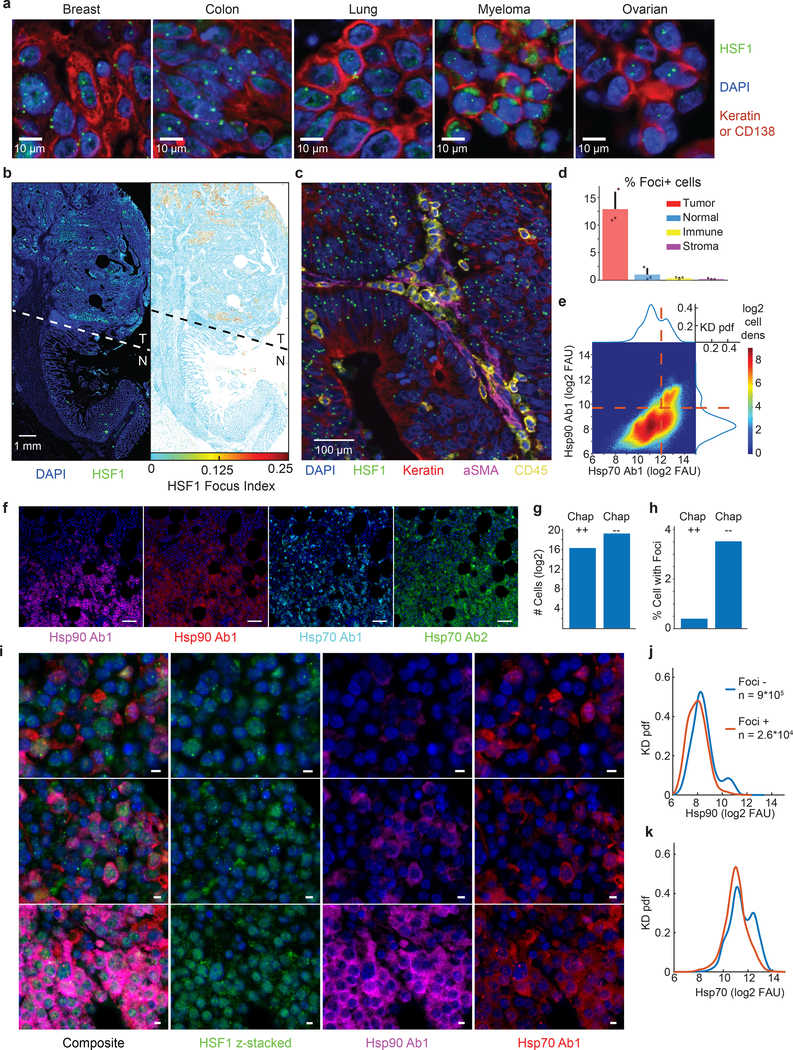

Figure 1. HSF1 foci are preferentially located in cancer cells in primary human tumors and are found in cells with low chaperone expression.

a. Composite images of t-CyCIF data of HSF1 (green), carcinoma marker pan-keratin (red) or myeloma marker CD138 (red) in a panel of cancer types. Similar observation of HSF1 foci were made in multiple patient samples per disease (n ~ 9 samples, see Source Data Figure 1 for exact numbers). b. Left, composite image of t-CyCIF data of HSF1 (green) and DAPI nuclear stain (blue) from a tissue section of colon adenocarcinoma with adjacent non-neoplastic colon tissue (T, tumor; N, normal). Right, 2D single-cell, spatially-averaged heat map of HSF1 foci from the t-CyCIF data. The color represents the HSF1 Focus Index (HSF1-FI, red high; blue low). c. Composite image of t-CyCIF data from colon adenocarcinoma showing nuclear stain (blue), HSF1 (green), keratin (red), αSMA (purple) CD45 (yellow). d. Quantification of t-CyCIF data from three whole tissue sections of colon adenocarcinoma indicating the percent of each cell type (tumor, normal, immune or stroma) classified as positive for HSF1 foci (average + SD, n = 3 patient samples, Foci+ cells defined as HSF1-FI > 0.05). e. 2D cell density map of single cell chaperone levels (~ 2*106 cells) from 9 myeloma patient samples analyzed by t-CyCIF. Dashed red lines represent the threshold set for defining cells positive for chaperone expression. f. Representative images of heterogeneity in chaperone levels in one of 9 myeloma patient tissues (scale bar 100μm). g. Bar graph of cells positive (Chap++) or negative (Chap--) for both Hsp70 Ab1 and Hsp90 Ab1 in 9 myeloma patient samples. h. Bar graph of cells positive for HSF1 foci (HSF1-FI > 0.05) with chaperone positive (Chap++) or negative (Chap--) cells from panel g. i. Representative images of HSF1 (green) and chaperones in one of 9 myeloma patient tissues (Hsp90 purple, Hsp70 red, scalebar 10μm). j and k. KD density of single cell chaperone levels comparing cells negative (red) and positive (blue) for HSF1 foci. See Source Data Figure 1 for details on samples, cell numbers and statistics.

In colon cancer resection specimens that we studied by t-CyCIF, the spatial distribution of cells with HSF1 foci was heterogeneous; clusters of tumor cells with high HSF1-FI were present adjacent to spatially distinct regions with low HSF1-FI (Fig.1b,c). Overall, ~13% of tumor cells were HSF1 foci-positive and ~95% of foci-containing cells were tumor cells (Fig.1d; Extended-Data Fig.1c,d). Analysis of a colon cancer tissue microarray comprising samples from 93 patients confirmed the non-uniform distribution of cells positive for HSF1 foci (Extended-Data Fig.1e), with foci largely restricted to tumor rather than stromal cells (Extended-Data Fig.1f–g). At the level of single tumor cells (n~250,000), we found chaperone levels positively correlated with total levels of nuclear HSF1 as postulated previously21 (Extended-Data Fig.1h–j; correlation coefficient (CC)>0.3). However, we did not observe a positive correlation between HSF1-FI and chaperone levels and in many cases, HSF1-FI was anti-correlated with chaperone protein expression (Extended-Data Fig.1k). In a cohort of nine myeloma/plasmacytoma samples, a malignancy that is highly dependent upon proteotoxic stress pathways, we also observed heterogeneous patterns of HSF1 foci formation and of HSP70 and HSP90 expression (Fig.1e–g; Extended-Data Fig.2). Myeloma cells expressing both HSP70 and HSP90 largely lacked HSF1 foci (Fig.1h–i). Congruently, cells containing HSF1 foci (HSF1-FI > 0.05) lacked HSP70 and HSP90 (Fig.1h–k; Extended-Data Fig.2).

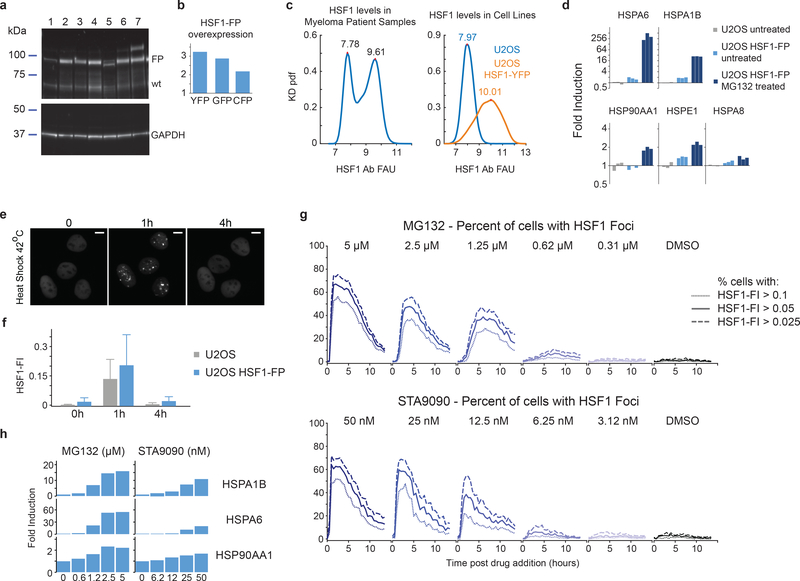

To study the relationship between HSF1 foci and chaperone expression, we tagged HSF1 with a yellow fluorescent protein (YFP) and introduced it into U2OS cells by lentiviral infection. The HSF1-YFP reporter protein was over-expressed relative to native HSF1, but the level of over-expression was similar to what was observed in tumor tissues (Extended-Data Fig.3a–c). Disruption of protein homeostasis by proteasome inhibition (MG132) or HSP90 inhibition (STA9090) triggered chaperone induction and foci formation. HSF1 accumulated in foci within 1–2 hours of adding drug and then re-mixed into the nucleoplasm over the next few hours (Fig.2a,b; Extended data Fig.3d–f; Supplementary Information Movie 1). The mean HSF1-FI, the frequency of cells containing foci and the amplitude of bulk chaperone-gene transcription measured by qPCR all increased with stress severity (Fig.2b; Extended-Data Fig.3g–h).

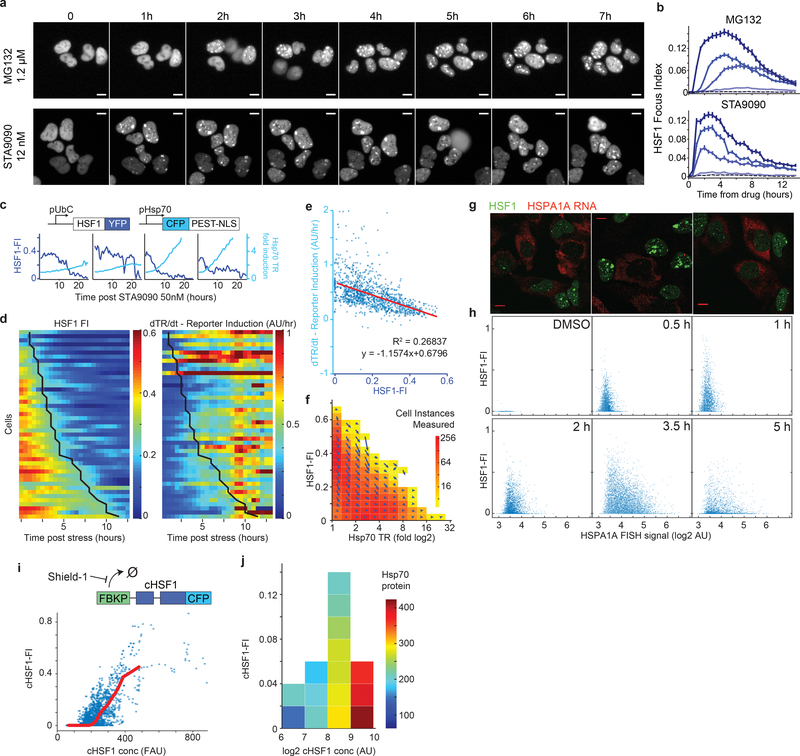

Figure 2. The dissolution of HSF1 foci promotes HSF1 transcriptional activity of heat-shock genes.

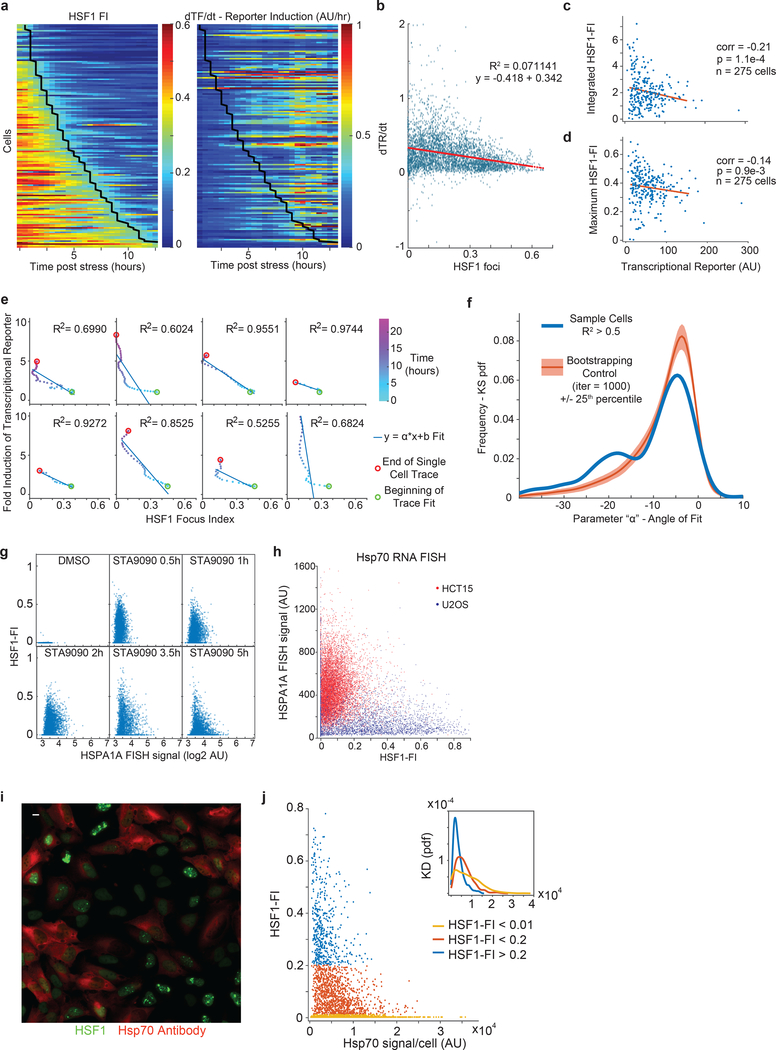

a. Time-lapse microscopy of U2OS HSF1-YFP cells treated with proteasome inhibitor MG132 and HSP90 inhibitor STA9090 (scale bar 10μm). b. Time-lapse microscopy average traces of single cells HSF1 Focus Index (HSF1-FI) in U2OS HSF1-YFP cells treated with proteotoxic compound gradients (darker color = higher dose; MG132: 5, 2.5, 1.25, 0.625, 0.312μM; STA9090: 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25, 3.12nM, DMSO control dashed line, 30 minutes intervals, mean +/− SEM, n ~ 260–550 cells, see Source Data Figure 2 for exact numbers). c-f. Time-lapse microscopy traces after 50nM STA9090. U2OS HSF1-YFP cells containing a transcriptional HSF1 reporter, a short-lived CFP driven by an HSP70 promoter. Similar results were observed in more than three independent experiments. c. Sample single-cell traces; dark blue, HSF1-FI and cyan, CFP fold induction. d. Time-lapse heatmaps for HSF1-FI and HSP70 Transcriptional Reporter (TR) induction (dTR/dt, time derivative); one cell per row. Cells shown have >5 fold CFP induction within 12 hours and max HSF1-FI > 0.25 (46 out of 158 cells, see Extended-Data Figure 4 for all traces). Black line, entry time of HSF1-FI < 0.2. e. Scatter plot of HSF1-FI versus dTR/dt from all instances from panel d (n=1170 cell instance measurements, red line = linear fit). f. Velocity plot: the blue arrow represents the direction and length of movement in the next time frames for HSF1-FI and TR. g-h. HSPA1A mRNA FISH (red) in U2OS HSF1-GFP (green) cells. g. Representative images (4.5 hours post 3μM MG132. scalebar 10μm). h. Single cell scatter plot timecourse (3.75μM MG132, n > 2000 cells per sample, see Source Data Figure 2 for exact numbers). i. Upper level, schematic of FKBP-cHSF1-CFP Shield construct (cHSF1). Lower level: plot of cHSF1-FI as function of total cHSF1 (all instances from n = 310 single cell traces). No exogenous stressors added. j. 2D histogram of single cells fixed and assayed by IF for cHSF1 concentration, cHSF1-FI and HSP70 protein after overnight incubation with 250nM Shield-1 (n = 2900 cells). No exogenous stressors added.

In single cells, we evaluated the relationship between HSF1-FI and HSF1 activity in three ways: i) with a stress-inducible HSP70 promoter (HSP70p) controlling expression of a CFP reporter, ii) with RNA-FISH for transcripts of endogenous HSPA1A, a well-characterized stress-inducible HSP70, and iii) with immunofluorescence for endogenous HSP70 protein (Fig.2; Extended-Data 4). After chemical perturbation with MG132 or STA9090, we tracked individual cells using time-lapse microscopy and recorded both HSF1-FI and reporter induction (n>200 cells). The levels of HSP70p reporter increased monotonically following exposure to stress but were negatively correlated with HSF1-FI (Fig.2c–e; Extended-Data Fig.4a–d); however, reporter production coincided temporally with foci resolution (Fig.2d,f; Extended-Data Fig.4e–f). With respect to endogenous mRNA production, a sharp increase in HSF1-FI preceded induction of HSPA1A mRNA. Moreover, in cells with increased HSPA1A mRNA expression, the extent of induction was anti-correlated with HSF1-FI at the single-cell level (Fig.2g–h; Extended-Data Fig.4g–h). Similar results were obtained for endogenous HSP70 protein; cells that had high HSF1-FI failed to efficiently induce HSP70 (Extended-Data Fig.4i–j). These data demonstrate that dissolution of HSF1 foci and not their formation correlated with HSF1 activity.

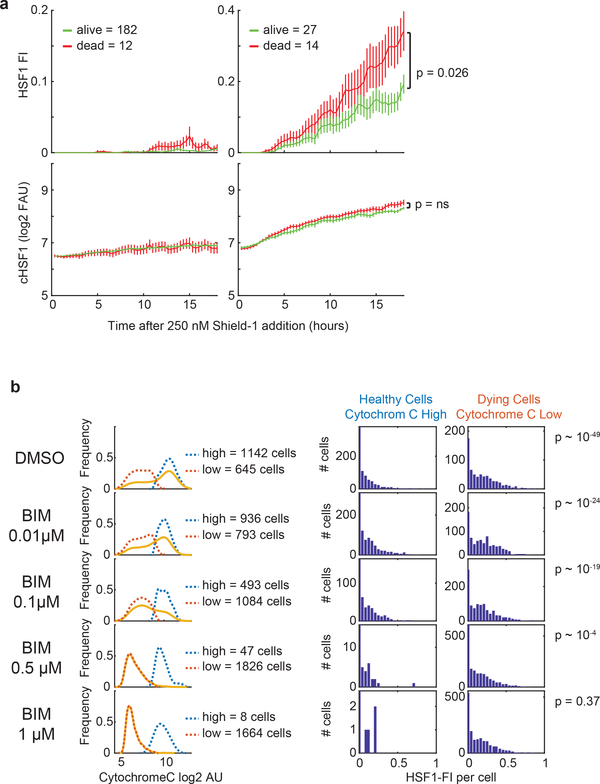

Proteotoxic stressors cause a wide range of physiological changes in cells, potentially representing confounding factors in our analyses. We therefore created a construct for increasing HSF1 levels in the absence of exogeneous stress. We used a destabilized FK506- and rapamycin-binding protein (FKBP) domain22 that regulates the induction of a constitutively active HSF1 (“cHSF1”) that spontaneously trimerizes and induces heat-shock gene transcription23. When cells were exposed to Shield-1, a cell-permeable FKBP ligand that stabilizes the destabilization domain, cHSF1 levels increased (Extended-Data Fig.3a), accumulating to different levels within cells. Past a critical concentration, numerous intranuclear cHSF1 foci formed (Fig.2i). Cells that accumulated more total cHSF1 expressed more HSP70. However, within groups of cells with comparable cHSF1 levels, ones with higher HSF1-FI expressed less HSP70 (Fig.2j). Thus, even without a stressor, formation of HSF1 foci is anti-correlated with chaperone expression.

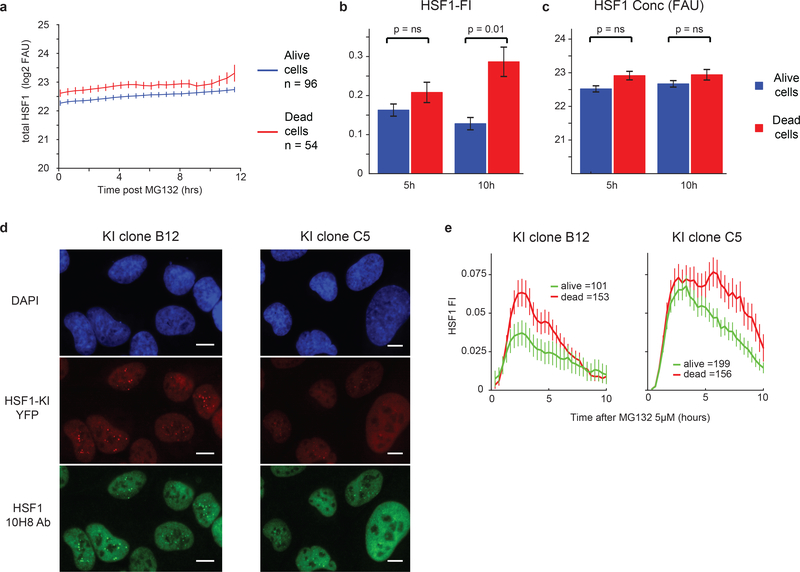

Because HSF1 foci negatively correlated with expression of chaperones, we hypothesized that cells in which foci persist should be more susceptible to stress. To test this hypothesis, we performed single-cell imaging (n~150) of cells exposed to MG132 and tracked individual cell fates over a 16-hour period (~40% died). Both surviving and dying cells formed foci, but cells in which foci dissolved were more likely to survive (Fig.3a; Extended-Data Fig.5a–c, p~10−2). We observed the same phenomenon in cells carrying an endogenous HSF1-YFP CRISPR knock-in fusion construct (Extended-Data Fig.5d–e). Moreover, cells in which cytochrome c translocated from mitochondria into the cytosol (a measure of mitochondrial outer membrane permeabilization, a key step in apoptosis induction, assayable by immunofluorescence microscopy) had higher HSF1-FI than cells in which cytochrome c remained mitochondrial (Fig.3b–c,p~10−49). Thus, cells with persistent foci were more likely to die by apoptosis. Notably, when formation of HSF1 foci was induced in the absence of stress using the FKBP fusion approach (Fig.2i), cells with higher HSF1-FI were more likely to die than cells with lower HSF1-FI (Extended-Data Fig.6a).

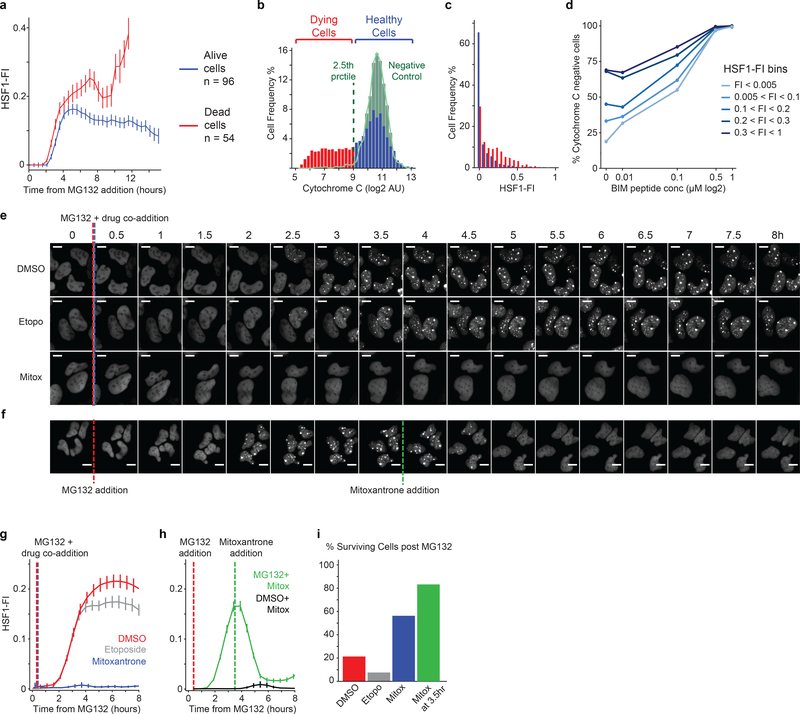

Figure 3. HSF1 foci triggered by proteotoxic stressors correlate with apoptotic death.

a. Time-lapse microscopy traces of HSF1 Focus Index (HSF1-FI) from single cells followed for 24 hours at 30-minute intervals following treatment with 2.5μM MG132 (mean +/− SEM). Cells are separated between those that died (red, n=54 cells, death time cutoff at 14 hours) and those that survived (blue, n=96 cells). b. Histogram of the distribution of cytochrome c in cells treated with MG132. Cells treated with 1.25μM MG132 for 8 hours were imaged for HSF1-YFP and then the cytochrome c levels were measured by immunofluorescence. The distribution of cytochrome c levels in control cells (green distribution and outline) was used to separate the stressed cells between a viable population of cells (blue, n = 1136 cells) and dying cells (red, n = 651 cells), which had released cytochrome c below the 2.5th percentile tail of the control distribution. c. In the same experiment shown in b, the distribution of HSF1-FI is shown in viable cells at 8 hours (blue) and in dying cells (red), two-sided KS test p-value ~ 10−49. d. % of cytochrome c negative cells in cell-bins separated by HSF1-FI levels following treatment with 1.25μM MG132 for 8 hours and then subjected to increasing concentrations of BIM peptide (n = 7165 cells total). e-i. U2OS HSF1-GFP cells treated with 2.5μM MG132 and either etoposide or mitoxantrone (20μM, see Source Data Figure 3 for validation and statistical details). e. Sample cell images from time-lapse imaging after drug co-addition (scale bar 10μm). f. Sample cell images from time-lapse imaging after mitoxantrone addition 3.5 hours after MG132 addition (scale bar 10μm). g-h. Single-cell HSF1-FI time dynamics after co-addition of 2.5μM MG132 and either etoposide or mitoxantrone 20μM (mean +/− SEM, n > 145 cells per condition, see Source Data Figure 3 for exact numbers). h. Single-cell HSF1-FI time dynamics with mitoxantrone addition after 3.5 hours of 2.5μM MG132 treatment (mean +/− SEM). i. Quantification of cell death during time-lapse imaging in panel g. after 22 hours of 2.5μM MG132.

To test if persistent HSF1 foci were associated with generation of pro-death signals, we measured the level of “apoptotic priming” at single-cell resolution24 by adding BIM BH3 peptide and measuring cytochrome c release. At equivalent concentrations of peptide, cells with higher HSF1-FI were more likely to release cytochrome c than those with lower HSF1-FI (Fig.3d; Extended-Data Fig.6b). Thus, cells with high HSF1-FI were more primed to undergo apoptosis.

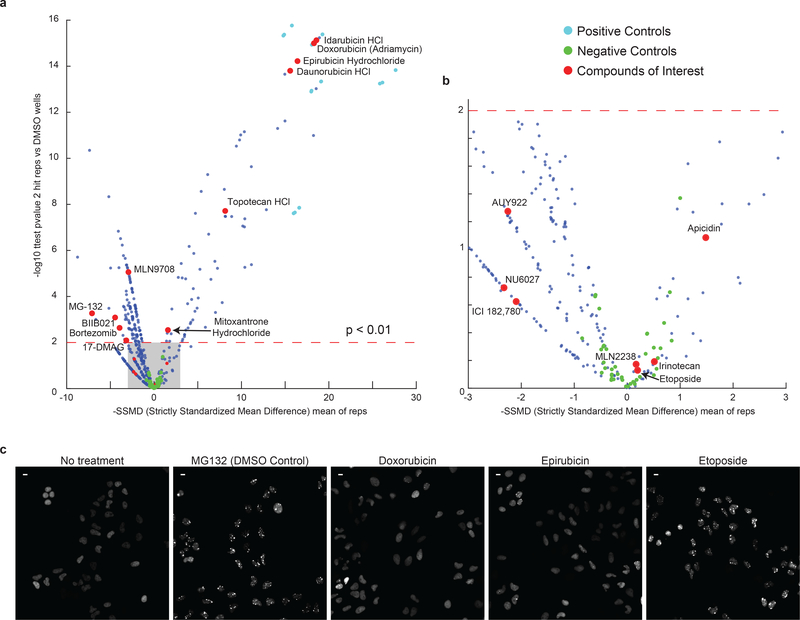

Using a chemical screen (Extended-Data Fig.7), we identified six topoisomerase inhibitors that prevented foci formation, potentially by modulating HSF1-DNA interactions2,16. We picked one compound that effectively prevented foci formation (mitoxantrone) and a functionally related but structurally distinct compound (etoposide) that did not and confirmed the screening results. By time-lapse imaging, we observed that mitoxantrone effectively prevented foci formation (Fig.3e,g) and also dissolved foci when applied after foci had formed (Fig.3f,h). This treatment rescued cells from MG132 cytotoxicity whereas etoposide enhanced death (Fig.3i). Cells can therefore be protected from apoptosis by small molecules such as mitoxantrone that antagonize focus formation.

The link between apoptosis and persistent HSF1 foci led us to investigate their biophysical properties. We triggered focus formation in two ways: using the FKBP/Shield-1 system (Fig.2i) and by treating cells with MG132. Time-lapsed imaging showed that foci that formed following cHSF1 induction were mobile and fluid, undergoing fusion, fission and necking (Fig.4a; Supplementary Information Movie 2). Following MG132 exposure, foci were initially small and spherical but gradually collided, coalesced and enlarged, eventually transitioning from rounded globular shapes into irregular structures. Such shape transitions are characteristic of phase-separated membrane-less bodies morphing from fluid to gel-like states (Fig.4b–d; Supplementary Information Movie 3)25.

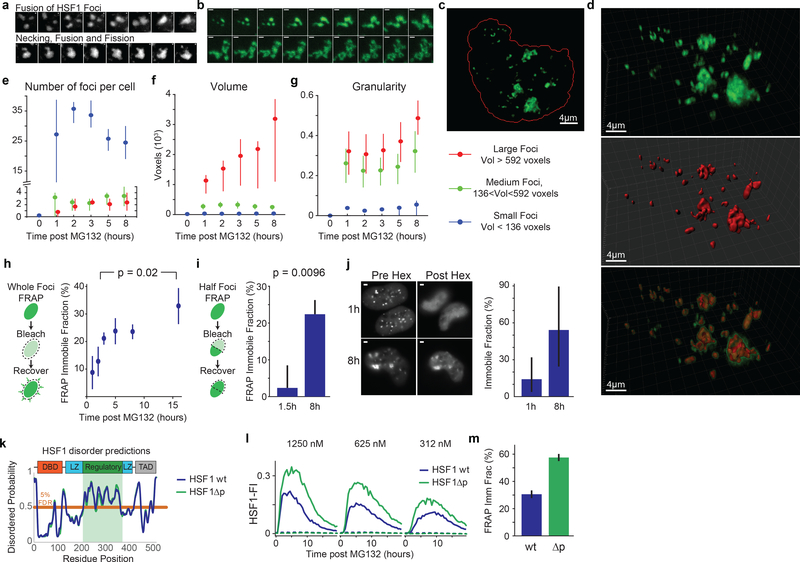

Figure 4. HSF1 foci are dynamics bodies that solidify within a few hours of stress.

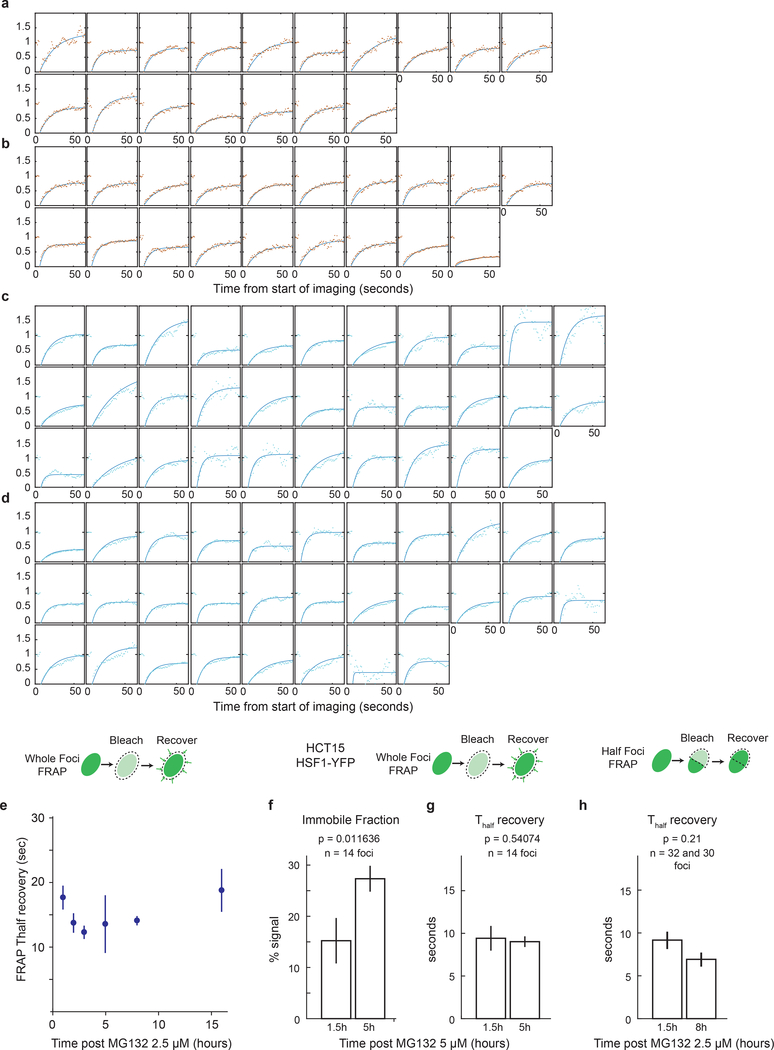

a. 3D rendered images of two FKBP-cHSF1-CFP foci undergoing fusion and fission following addition of the Shield-1 (time interval = 5 min, scale bar 1μm, no exogenous stressors, Supplemental Information Movie 2, n ~ 10 similar independent observations). b. Live cell time-lapse imaging of a single cluster of foci with deconvolved z-stacks of HSF1-GFP in live U2OS cells post 2.5μM MG132 (10 minutes interval, scale bar 1μm, see Supplemental Information Movie 3, n ~ 50 foci from 8 cells). c-g. Time course of U2OS HSF1-GFP cells post 2.5μM MG132 Z-stack, deconvolution and 3D rendering (377 cells in total, 550 foci per timepoint, see Source Data Figure 4 for exact numbers). c. Sample image, red line outlines nucleus. d. 3D view of cell from c. with surface rendering (red) of HSF1 foci (green) and overlay (Imaris software). e-g. Statistics on HSF1 foci, subdivided by foci size. e. Number of HSF1 foci per cell, f. foci volume g. granularity (mean +/− 25th percentile). h. Whole focus FRAP. Immobile fraction estimates after 2.5μM MG132 (mean +/− SEM, n = 28, 17, 27, 19, 19 and 10 foci, two-sided KS p-value). i. Half-focus FRAP. Immobile fraction estimates 1.5 and 8 hours after 2.5μM MG132 (mean +/− SEM, n = 32, 30 foci, two-sided KS p-value). j. Sample images and quantification of foci dissolution by 1,6-hexanediol post 10μM MG132 (n = 85, 103 cells, median +/− 25th percentiles, scale bar 2μm). k. Disorder probability prediction of wild type and mutant HSF1 (HSF1Δp, all serine residues in the regulatory domain replaced by alanines). Negative scores are indication of intrinsic disorder. l. Time-lapse microscopy traces of population HSF1-FI averages post MG132 in U2OS cells; comparison of wild type HSF1 with HSF1Δp (n > 1200 cells, see Source Data Figure 4 for exact numbers). Dashed lines are DMSO controls. m. Fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) of HSF1-CFP wild type and HSF1Δp, 5 hours after 5μM MG132 (n = 23, 27 foci, mean +/− SEM).

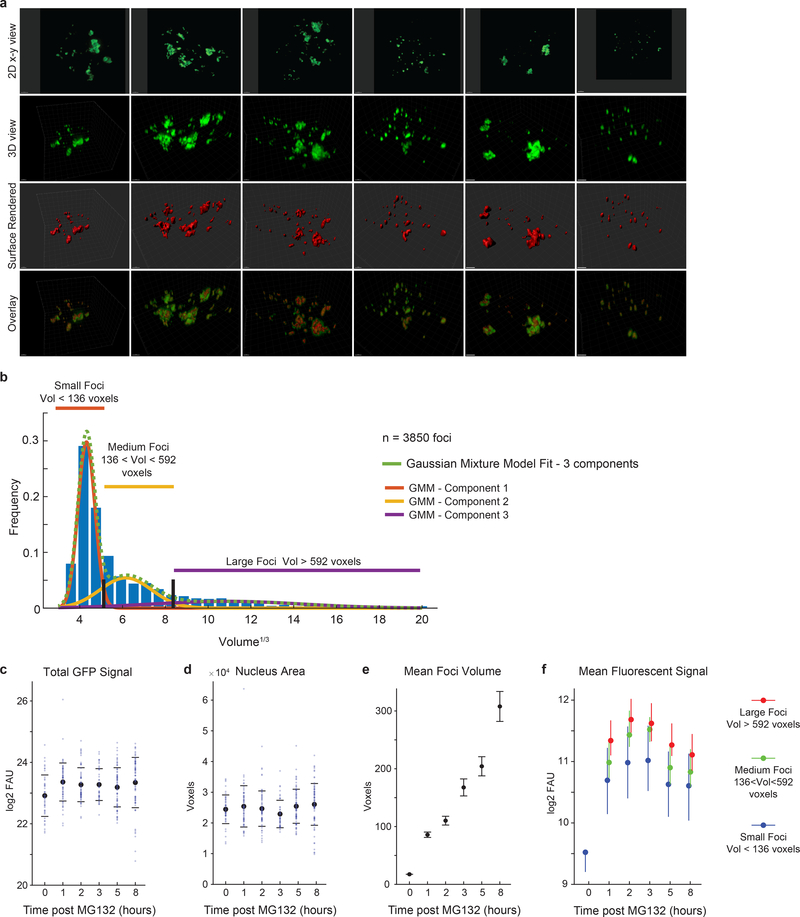

To characterize the number, size, sphericity and fusion of HSF1 foci as a function of time, we imaged foci at high resolution in 3-dimensions (Fig.4c–g; Extended-Data Fig.8a). Cells were treated with MG132 for different periods of time, fixed and then imaged; Z-stacks were collected and deconvolved to reconstruct the volumes of HSF1 foci. We observed that individual cells often had 20–30 HSF1 foci with dramatic heterogeneity in size and shape, consistent with prior reports6; we categorized foci as small, medium and large (Extended-Data Fig.8b). Total volume of foci per cell increased with increasing time of MG132 exposure. Small foci formed rapidly and then diminished in number starting two hours after MG132 exposure (Fig.4e). The number of medium-sized and large-sized foci quickly plateaued (Fig.4e), while their volume continued to increase (Fig.4f, Extended-Data Fig.8e,f). We conclude that small foci coalesce into larger foci, consistent with our live cell imaging data (Fig.4a–b). Furthermore, between 3 and 8 hours, focus granularity (a measure of 3-dimensional shape irregularity) increased substantially, particularly in large foci (Fig.4g), suggesting that HSF1 foci underwent a phase transition.

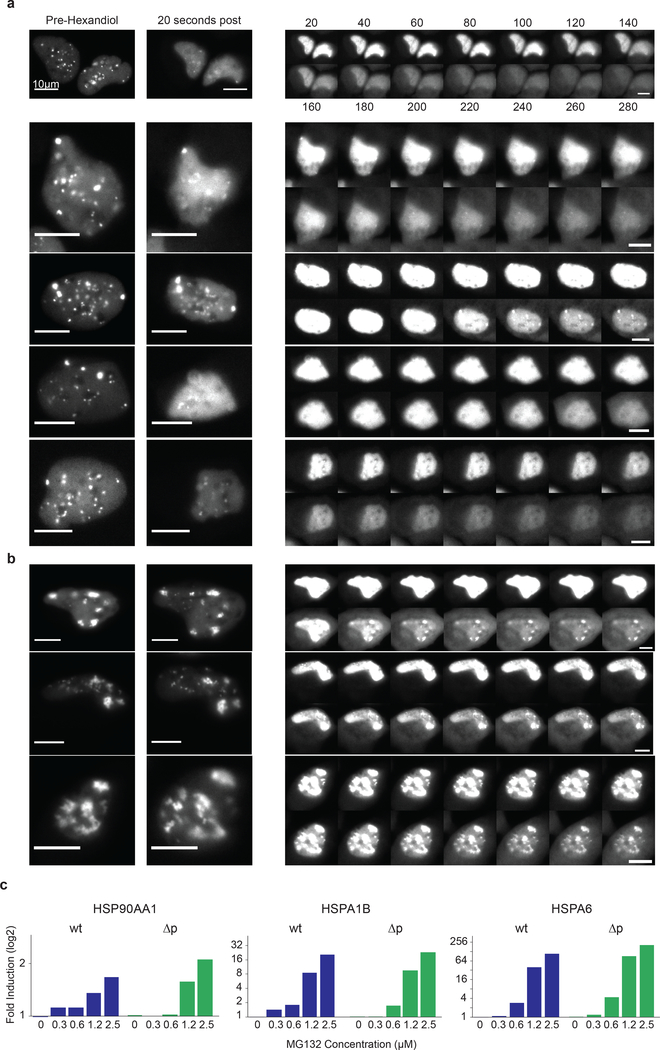

To probe the phase-transition hypothesis, we performed fluorescence recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) between 1 and 16 hours after adding MG132. Molecules restricted from exchanging freely, as measured by their movement away from photobleached areas, are quantified by the FRAP immobile fraction. One hour after adding MG132, the immobile fraction was <10%, demonstrating rapid re-mixing between foci and nucleoplasm (Fig.4h; Extended-Data Fig.9a–g). The immobile fraction gradually increased up to 40% at 16 hours demonstrating that HSF1 was progressively trapped within foci. To assess the motility of molecules within each focus, we bleached half a focus and measured recovery. Data were similar to those from FRAP on entire foci: reduced mobility of HSF1 molecules within condensates at later times after stress (Fig.4i; Extended-Data Fig.9h). These findings were supported by assessing the immobile fraction using 1,6-hexanediol, an aliphatic compound that disrupts hydrophobic interactions and dissolves liquid condensates but not solid protein assemblies26. One hour after MG132 addition, HSF1 foci were efficiently dissolved by 1,6-hexanediol (Fig.4j; Extended-Data Fig.10a), but, after 8 hours, the immobile fraction increased to 54% (Fig.4j; Extended-Data Fig.10b).

Intrinsically disordered domains have been implicated in phase-separation and formation of membrane-less compartments27. Most of HSF1 folds into structured domains, except for the regulatory domain (aa203–384)28. Upon stress, HSF1 is extensively phosphorylated on serine residues in this domain; events dispensable for chaperone induction3,29,30. To prevent phosphorylation, we mutated all 33 serine residues in the regulatory domain to alanine (“HSF1Δp”). The regulatory domain has a high predicted probability of being disordered and these mutations did not change the disorder probability (Fig.4k). HSF1Δp did not spontaneously form foci and did not have a dominant negative effect on transcription (Extended-Data Fig.10c). In cells treated with MG132 (312–1250nM), HSF1-FI was 50–80% higher for HSF1Δp than wild-type HSF1 (Fig.4l). Moreover, FRAP showed that the immobile fraction of HSF1Δp foci was nearly twice that of wild-type HSF1 (Fig.4m), suggesting that post-translational modifications can modulate HSF1 solidification.

Our data suggest that nascent HSF1 foci represent liquid-liquid phase condensates with dynamic properties. Foci dissolution in some cells coincides with activation of HSF1 transcriptional targets and cell survival; in other cells, HSF1 is sequestered within granular foci by a phase transition, thereby down-regulating HSF1 function. Cells with persistent HSF1 foci are primed for apoptosis, consistent with a role for foci in reducing cytoprotection by chaperones. The heterogeneity of HSF1 foci in human tumors suggests that most malignant cells may be devoid of inhibitory foci, consistent with prior evidence that HSF1 expression promotes tumorigenesis31,32.

While translocation of proteins between membrane-bound organelles is an established mechanism of biological regulation, protein phase separation into membraneless organelles is recently discovered33 with newly defined roles in transcriptional regulation34, DNA repair35, translational control36,37 and the cell cycle38. The connection between transport among organelles and function, however, is not always apparent particularly in the absence of single-cell approaches. In the case of HSF1, the similarity between the conditions and timescales for foci induction and for chaperone expression has led to the idea that HSF1 foci formation positively correlates with chaperone gene expression6–10. Indeed, recent evidence supports a role for yeast HSF1 in co-assembling with actively transcribed heat-shock genes into foci10. However, the situation appears different in human cells in which, unlike in yeast, HSF1 foci do not form at HSP promoters6,13,14,16,17. Instead of promoting chaperone expression, human HSF1 foci appear to negatively regulate HSP transcription and promote apoptosis, possibly because foci sequester HSF1 from HSP promoters but perhaps through other yet undiscovered mechanisms. Rather than simply marking cells destined for apoptosis, the kinetics of foci formation relative to chaperone gene induction and their reversibility support a functional connection between foci, chaperone gene regulation and death.

Our data support a model in which phase-separated HSF1 foci serve as ‘sensors’ regulating cell fate. Jolly et al. proposed HSF1 foci might serve as ‘central depots’ for dispensing transcriptionally competent HSF1 trimers6. Such membraneless organelles may make the biophysical properties of HSF1 sensitive to a wide variety of molecular events triggered by stress, including activation of protein kinases and myriad factors impacting cellular conditions36. The relationship between foci persistence and reduced chaperone production, present in both cell culture and human tissues, suggests an adaptive value for a mechanism that disables HSF1 under extreme conditions and results in heterogeneous cell fates. It has been proposed that heterogeneity in mechanisms regulating cell fate can increase the information content of signaling systems39. Sequestration of HSF1 in solidifying foci may mark cells with excessive proteotoxic damage; when the damage is too great, apoptosis ensues40. Exploiting biophysical properties of phase transitions may represent a general strategy to encode and decode information at the molecular level.

METHODS

Experimental models and subject details

Cell Lines

U2OS and HCT15 cells were grown in RPMI 1640 Medium with GlutaMAX Supplement with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin. 293T cells used for lentivirus production were grown in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium with 10% fetal bovine serum and 1% penicillin/streptomycin.

Human Tissue Sections

Formalin fixed, paraffin embedded (FFPE) tissue sections of colon adenocarcinoma, ovarian carcinoma, and plasmacytoma were retrieved from the archives of the Department of Pathology at Brigham and Women’s Hospital. Discarded human formalin fixed paraffin embedded tissue samples were used after diagnosis under protocol 2018P001627 (reviewed and managed by the Partners Healthcare Institutional Review Board at Brigham Health; protocol and approval available from author on request). Under this protocol, waiver of consent was authorized and granted by the IRB. The study is compliant with all relevant ethical regulations regarding research involving human tissue specimens. The Principal Investigator is responsible for ensuring that this project was conducted in compliance with all applicable federal, state and local laws and regulations, institutional policies and requirements of the IRB. Commercially available breast and lung carcinoma FFPE tissue sections were purchased from Pantomics, Inc.

Experimental methods

t-CyCIF

Tissue-based cyclic immunofluorescence (t-CyCIF) was performed as described19. In brief, the BOND RX Automated IHC/ISH Stainer was used to bake FFPE slides at 60°C for 30 minutes, to dewax using Bond Dewax solution at 72°C, and to perform antigen retrieval using Epitope Retrieval 1 solution at 100°C for 20 minutes. Slides underwent multiple cycles of antibody incubation, imaging, and fluorophore inactivation. All antibodies were incubated overnight at 4°C in the dark. See Supplementary Information Table 1 for the complete list of antibodies that were used. Slides were stained with Hoechst 33342 for 10 minutes at room temperature in the dark following antibody incubation in every cycle. Cover slips were wet-mounted using 200 μL of 10% glycerol in PBS prior to imaging. Images were taken using a GE IN Cell Analyzer 6000 and the following filter sets: ‘DAPI channel’ with 455-nm peak excitation/25-nm half-bandwidth, ‘488 channel’ with 525-nm peak excitation/10-nm half-bandwidth, ‘555 channel’ with 605-nm peak excitation/26-nm half-bandwidth, and ‘647 channel’ 706.5-nm peak excitation/36-nm half-bandwidth. Fluorophores were inactivated by submerging slides in a PBS solution with 4.5% H2O2 and 20 mM NaOH and placing them under an LED light source for 2 hours.

Plasmid Construction and Genome Editing

Plasmids were generated via Gateway Cloning (ThermoFisher) or Gibson assembly. Plasmid sequences were confirmed using Sanger Sequencing. To generate stable lines, constructs containing fluorescent tags were subcloned using DH5α competent cells into a vector for lentiviral production. Lentiviruses were packaged into 293T cells with a 3rd generation lentiviral system, and the supernatant was used to infect U2OS or HCT15 cells. The cells were selected with puromycin (10–50 μg/mL) or neomycin (400 μg/mL) for 14 days beginning 72 hours post-infection. See Supplementary Information Table 2 for details on plasmids used.

IDT GeneBlock technology was used to clone the HSF1Δp mutant.

Gene Block sequence: TGATGCTGAACGACgcTGGCgcAGCACATgCtATGCCCAAGTATgctCGGCAGTTCgCaCTGGAGCACGTCCACGGCgCtGGCCCCTACgCtGCtCCCgCaCCAGCaTACgctgctgCagcaCTCTACGCaCCTGATGCTGTGGCCgcagCTGGACCCATCATCgCaGACATCACCGAGCTGGCTCCTGCCgcaCCCATGGCCgCtCCCGGCGGGgctATAGACGAGAGGCCCCTAgCtgcagctCCCCTGGTGCGTGTCAAGGAGGAGCCCCCCgctCCGCCTCAGgcaCCCCGGGTAGAGGAGGCGgcTCCCGGGCGCCCAgCTgCaGTGGACACCCTCTTGgCaCCGACCGCaCTCATTGACgCtATCCTGCGGGAGgcTGAACCTGCCCCCGCagCtGTCACAGCaCTCACGGACGCtAGGGGCCACACGGACACCGAGGGCCGGCCTCCCgCaCCCCCGCCCACCgCtACCCCTGAAAAGTGCCTCgctGTAGCCTGCCTGGACAAGAAT

Time-lapse Microscopy Following Stress Perturbations

For time-lapse microscopy experiments, cells were seeded into 96 well glass bottom plates with 200 μL of media two days prior to imaging (Brooks Automation Inc. 96 Well Glass Bottom Black Plates (MGB09612LGL)). A 10 μL volume of stress perturbing molecules diluted in media was added to wells at various time points before imaging. MG132 was used at final concentrations ranging from 0.06 μM to 10 μM to induce proteasome inhibition. STA9090 (Ganetespib) was used at concentrations ranging from 6.25 nM to 500 nM to induce HSP90 inhibition. Time-lapse images were taken with the GE IN Cell Analyzer 6000, Perkin-Elmer Operetta High-Content Imaging System, or Nikon Eclipse Ti Live Cell Imaging System. Cells were kept in a controlled chamber of 37°C temperature and 5% CO2. Time intervals between images varied based on experiment, ranging from 5 to 30 minutes (exact intervals are noted in the Figure legends).

Tissue Culture Cell Fixation and Immunofluorescence

Standard fixation of cultured cells was performed with 4% paraformaldehyde diluted in phosphate buffer saline (PBS) for 10 minutes at room temperature (unless otherwise specifically specified).

After fixation cells were washed 3X with PBS, incubated in PBS 0.5% Triton X-100 (ThermoFisher Scientific, Cat# 85111) for 10 minutes at room temperature, washed 3X with PBS, incubated in blocking buffer (PBS 2% BSA, 0.1% Triton X-100) for 30 minutes at room temperature. Antibody incubation was performed in blocking buffer at 4°C overnight for primary antibodies (1:100 dilution) and 1 hour at room temperature for secondary antibodies (1:1000 dilution).

Western Blotting and Quantification

Standard laboratory Western Blotting techniques were used. Antibodies information and technical details can be found in Supplementary Information Table 1. PVDF membrane was probed overnight with primary antibodies (against HSF1 or GAPDH), stained overnight with fluorescently labelled secondary antibodies and imaged using a BioRad ChemiDoc MP Imaging System. Band quantification was performed in ImageJ software as follows. For each lane the tagged HSF1 band (~100kDa) was normalized to the respective GAPDH band intensity (both were first background subtracted). The signal from each lane was subtracted to the signal in lane 1 (no HSF1-FP lane; HSF1-Fluorescent Protein lane) and divided by the respective intensity value of endogenous HSF1 band (~72kDa).

qPCR of Heat Shock Genes

U2OS cells were treated with proteotoxic stressors and collected by cell scraping at specified times post treatment. Total RNA was isolated with QIAGEN RNeasy Mini Kit and synthesized to cDNA via reverse transcription. qPCR was used to quantify gene abundance of HSPA1B, HSPA6, and HSP90AA1 using SYBR Green dye. ACTB and GAPDH gene abundance were used to normalize qPCR signal and DMSO treated controls were used to calculate fold change of gene expression using the standard ΔΔCt metric. Primer sequences below:

| HSPA6: | [GATGTGTCGGTTCTCTCCATTG, CTTCCATGAAGTGGTTCACGA] |

| HSPA1A/B: | [TTTGAGGGCATCGACTTCTACA, CCAGGACCAGGTCGTGAATC] |

| HSP90AA1: | [AGGTTGAGACGTTCGCCTTTC, AGAGTTCGATCTTGTTTGTTCGG] |

| ACTB: | [CATGTACGTTGCTATCCAGGC, CTCCTTAATGTCACGCACGAT] |

| GAPDH: | [GGAGCGAGATCCCTCCAAAAT, GGCTGTTGTCATACTTCTCATGG] |

RNA-FISH

mRNA transcripts of HSPA1A were visualized using the Stellaris RNA fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) assay and protocol. Cells were grown on glass coverslips within 6 well low attachment plates and treated with 3.75 μM MG132 or 100 nM STA9090 for 0.5, 1, 2, 3.5, or 5 hours. Cells were then fixed with a formamide buffer solution and permeabilized with 70% ethanol. A custom probe set against the HSPA1A gene product was purchased from Stellaris (available upon request). FISH probes were diluted to a 125 nM concentration and incubated in a humidified chamber for 16 hours at 37°C in the dark. Nuclei were counterstained with a 5 ng/mL DAPI solution for 30 min at 37°C in the dark. Cells were mounted with Vectashield Mounting Medium and sealed with nail polish. HSF1 protein and HSPA1A transcript were imaged using DAPI, FITC and Cy5 channels on the GE IN Cell Analyzer 6000 imaging system with a 60X/0.95 NA objective.

Shield-1 Experiments

Live cell experiments were carried out in U2OS HSF1-mVenus (YFP) FKBP-cHSF1-TQ2 (CFP) cells in the presence of Shield-1 500 nM (Takara Bio USA Cat# 632189). For correlation with HSP70 protein expression cells were imaged after 20 hours in the presence of 250 nM Shield-1 followed by immunofluorescence against HSP70 (C92 antibody from Abcam).

Cytochrome C Experiments

U2OS HSF1-mEGFP cells were plated in 96 well plates 2 days prior to the assay and treated with 1.25 μM MG132 final concentration. After 8 hours the media from wells was replaced with MEB buffer (150 mM Mannitol, 10 mM HEPES-KOH pH 7.5, 50 mM KCl, 0.1% BSA, 5 mM succinate). This was repeated twice to remove any traces of cellular medium. Media was replaced with MEB buffer containing digitonin (0.002%) and different concentrations of 1 μM, 0.5 μM, 0.1 μM and 0.01 μM BIM per well in a total of 100 μL. The plate was incubated at 30ºC for 1 hour in an ambient air incubator. 50 μL of medium was aspirated from each well. Cells were fixed with formaldehyde to achieve a final concentration of 4% and incubated for 15 minutes followed by addition of 35 μL N2 buffer (1.7 M Tris, 1.25 M Glycine, pH 9.1) to quench formaldehyde and further incubation for 15 minutes at room temperature. Cells were stained with 1:1000 cytochrome c-AlexaFluor647 antibody and 1:2000 Hoechst-33342 (6 ng/μL final concentration) diluted in ISB (Intracellular Staining Buffer, 1% saponin, 10% BSA, 20% FBS, 0.02% sodium azide, PBS, sterile filtered and stored at 4°C). The plates were incubated overnight at 4°C. Plates were washed with PBS. Cells were imaged once live right before MEB buffer replacement (for HSF1 fluorescence and foci quantification) and then again after fixation and overnight staining (for cytochrome c abundance).

1,6-hexanediol Experiments

U2OS HSF1-mEGFP cells were grown in 96 well glass bottom plates for 2 days. Prior to imaging, the media was replaced with fresh RPMI media containing 10 μM MG132. At 2 or 8 hours post MG132 treatment, the media was replaced again with fresh media containing 10 μM MG132 and 10% 1,6-hexandiol (Sigma-Aldrich Cat# 240117). Cells were imaged once pre-media change and afterward for 10 minutes at intervals of 20 seconds. Nuclei and HSF1 foci were segmented manually using Fiji before media change and at 60 seconds (third timepoint) after 1,6-hexanediol addition. The immobile fraction was calculated on a single cells basis as the ratio of HSF1 in foci prior to 1,6-hexanediol addition over 60 seconds post.

Fluorescence Recovery after Photobleaching (FRAP)

FRAP experiments were performed at the Confocal Core at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, Boston, MA on the Zeiss LSM 800 with Airyscan Confocal Laser Scanner microscope with a 63X/1.43 NA oil objective using the Zen 2.3 software. The experiments were conducted within an environmental chamber at 37°C and 5% CO2. Single cells were imaged for a total of 65 seconds at a maximum rate of 1 frame/second. After 5 pre-bleach frames, the fluorescence signal from a user-defined region of interest (ROI) was bleached with 488 nm laser at 100% power. The signal from the bleached ROI and a neighboring normalization ROI was measured for 60 seconds afterwards. The ROI was defined as either a full HSF1 focus (“whole-focus FRAP”) or as half of the area of a single HSF1 focus (“half-focus FRAP”). At each time point, single cells were imaged sequentially. The foci signal was normalized to control for photobleaching effects. For the whole-focus FRAP the entire cell area was used to normalize the signal. For the half-focus FRAP, the unbleached area of the same focus was used for signal normalization. The immobile fraction and half-life recovery were calculated by least square fitting of an exponential curve f(t) = A(1-e−τt) to the normalized fluorescence recovery curve using MATLAB.

Disorder Probability Calculation

Disorder probabilities of amino acid sequences were computed using the PrDOS Protein Disorder prediction system (http://prdos.hgc.jp/cgi-bin/top.cgi) with a 5% false positive rate.

Image Analysis and Quantification

Image analysis was performed in MATLAB using custom codes (full codes available on GitHub https://github.com/santagatalab/). Below are descriptions of steps implemented by codes for each type of analysis.

Cell segmentation, Foci Segmentation and HSF1 Focus Index (HSF1-FI) Analysis

For live cell time-lapse, plate-based immunofluorescence, and RNA FISH image analysis, the following steps were performed.

-

Nuclear segmentation

Mask creation using either DAPI stain or the HSF1 fluorescent signal on a tile-by-tile basis. Performance of segmentation as follows:- Background and flatfield correction by morphological manipulation (image opening and closing);

- Threshold estimation by fitting the non-background pixel distribution to a double normal distribution, then taking the mean and standard deviation (sigma) of the highest of the two gaussian fits and setting the threshold to 2 standard deviations below mean;

- Single-cell object detection by application of a gaussian filter and peak detection;

- Watershed transformation on thresholded image of objects determined in step c.;

- (Optional). Verification of watershed partition accuracy using solidity as an evaluation metric.

-

Foci segmentation

A foci mask is created as follows:- Application of spatial standard deviation filter to corrected images from (1) to detect changes in the signal intensity;

- Normalization of the spatial deviation to the original image (or to the square root of the original image) to obtain a spatial coefficient of variation (sCV image);

- Thresholding of sCV image to identify boundaries of localized intense signal, or foci, and fill holes with morphological manipulations;

- Intersection of the resulting foci segmentation with the nuclear segmentation image to attribute each focus to a single nucleus.

- An example of the resulting masks can be found in Source Data Extended-Data Figure 1.

-

Signal quantification

Using the masks generated in 1) and 2), calculation of single-cell signal from the fluorescence images as follows:- Nuclear Median Signal per Single Cell. Loading of fluorescent images and measurement of the median of the signal intensity in the segmented area for each nucleus;

- Cytoplasmic Median Signal per Single Cell. Creation of a cytoplasmic mask by dilating the nuclear mask and subtracting the nuclear portion, leaving a ring of pixels around the nucleus. Loading of fluorescent images and measurement of the median signal intensity for the cytoplasmic mask of each cell;

- HSF1 Foci Signal. Measurement of the total amount of HSF1 signal from both the total nuclear mask and the foci segmentation masks from the channel with tagged HSF1.

HSF1 Focus Index – HSF1-FI

The HSF1 Focus Index (HSF1-FI) is a single-cell metric used throughout the study. HSF1-FI is defined as the ratio between the HSF1 Foci Signal in the nucleus of a cell and the total HSF1 signal from the same cell. HSF1 foci positive cells are defined as cells for which the HSF1-FI is higher than a threshold (HSF1-FI threshold = 0.05 unless otherwise specified). The HSF1-FI index is a relative metric used to compare cells within the same experiment, not representing absolute values of HSF1 protein within foci.

Single-Cell Tracking from Live-Cell Imaging

The p53cinema MATLAB GUI (GitHub: https://github.com/balvahal/p53CinemaManual) developed by Jose Reyes and Kyle Karhohs in the laboratory of Galit Lahav, Systems Biology Department, Harvard Medical School was used to register single cells through time lapse images using nuclear centroid locations. The GUI was then used to inspect the morphology of each cell at every time point and mark the time point of cell death.

t-CyCIF Analysis

Analysis of t-CycIF data is divided into three major steps:

- Pre-processing of raw images into background corrected aligned stacks of images;

- For the colon tissue resection used in Figure 1, darkfield subtraction and flatfield correction was performed using BaSiC, a Fiji plugin developed at the Helmholtz Zentrum München - German Research Center for Environmental Health ICB Institute of Computational Biology, Quantitative Single Cell Dynamics Group (available at https://www.helmholtz-muenchen.de/icb/research/groups/quantitative-single-cell-dynamics/software/basic/index.html#c158341). For the TMA and the plasmacytoma/myeloma datasets the correction was done on a tile-by-tile basis using morphological image filtering in MATLAB.

- Images from each cycle were registered and stitched across cycles using the DAPI signal on a tile-by-tile basis using normxcorr2 function in MATLAB.

- Image Analysis. Segmentation of nucleus and cytoplasm, matching of cells between cycles of imaging, measurement of markers and HSF1 foci at single-cell level;

- The nuclear, cytoplasmic, and foci segmentation was performed as described above in the Cell segmentation, Foci Segmentation and HSF1 Focus Index (HSF1-FI) Analysis sections.

- The cells were matched using a nearest neighbor search (knnsearch function in MATLAB) and then checked for pixel area overlap of at least 50%.

- Data Analysis and Plotting. Cell type calling by thresholding of cell type specific markers (Pan-cytokeratin, CDX2, CD45, CD20, CD3D, IBA1), plotting variables, and calculating dependencies.

- Thresholding was performed by plotting estimated probability density function (ksdensity function in MATLAB) of log2 signal from all cells in the tissue section or all TMA cores and looking for a tail or bimodal division.

- Once the thresholds were identified the cell type calling for the colon tissue resection specimen was performed with the following criteria

- Cancer Cells = high Keratin AND high CDX2 AND nuclear Keratin < cytoplasmic Keratin;

- Immune Cells = low Keratin AND low CDX2 AND high CD45

- Stromal Cells = low Keratin AND low CDX2 AND high αSMA AND NOT Immune Cells

- Normal Cells = the tile of regions of normal tissue were manually defined by pathology review

- Once the thresholds are identified the cell type calling for the colon tissue microarray (TMA) was performed with the following criteria

- Cancer Cells = high Keratin AND high CDX2 AND nuclear Keratin < cytoplasmic Keratin;

- Immune Cells = low Keratin AND low CDX2 AND (high CD45 OR high CD20 OR high CD3D OR high IBA1)

- Stromal Cells = low Keratin AND low CDX2 AND high αSMA AND NOT Immune Cells

- Normal Cells = no normal cell gate was defined as the cores of the TMA are selected to within the tumor region of the resection specimen.

Z-stack imaging and 3D image analysis (deconvolution and surface rendering)

Image acquisition: For each timepoint, Z-stacks were acquired on a Deltavision Elite (GE Life Sciences). Samples were illuminated through a 60x/1.42NA objective lens with excitation light passing through a bandpass filter of 475/28. Fluorescence emission was collected through a bandpass filter of 525/48 and sampled on an Edge 5.5 sCMOS camera (PCO) at 108nm and 200nm in the lateral and axial axes respectively. To minimize spherical aberration, the immersion oil refractive index was matched until point spread functions from within the sample itself were approximately symmetrical as described by Hiraoka et al. Biophys, 1990. Z-stacks were deconvolved using the constrained iterative algorithm with an appropriately matched optical transfer function in SoftWorx (GE Healthcare).

Nuclei segmentation

A random forest model was trained on max projections of 6 datasets across different timepoints. The model included features such as image gradients, Laplacian of Gaussians (LoG), standard deviation, and entropy and was trained using PixelClassifier (https://hms-idac.github.io/MatBots/). From the class probability maps, a custom script was written in MATLAB 2018b (MathWorks) to identify local maxima as markers for watershed segmentation. Nuclei that were in contact with the image border were not considered for further analysis.

Foci detection

Within each segmented nucleus, we first identified the centroids for all foci. Foci that were larger than three times the limit of the theoretical resolution of the optical system were identified by background subtraction of the deconvolved images, Otsu thresholding, and calling the standard regionprops3 function in MATLAB. Objects that were closer to the 3-fold resolution limit were more accurately detected using a 3D point source detection algorithm developed by Aguet et al. Dev Cell 2013 on the raw images. We specified the standard deviation of the Gaussian filter as 1.5 and 2.1 pixels in the lateral and axial axes respectively after identifying the mean standard deviation of PSFs (point spread functions) from point sources in the one-hour datasets. The centroid positions of all foci were determined to subpixel accuracy.

Foci analysis

From the centroid positions, we calculated the volume and granularity for each focus from the standard regionprops3 function in MATLAB. All features were exported on a single foci basis to a comma separated file.

Surface rendering

The deconvolved images were imported into Imaris 9.0.2 (Bitplane) where foci were rendered using the surface module. Datasets were smoothed and background subtracted using filter sizes of 0.1 microns and 1 micron respectively.

Chemical Screen for HSF1 foci modifiers

To find a way to modify HSF1 foci, we performed a chemical screen. In a 96-well arrayed format, we treated our HSF1-GFP reporter cell line simultaneously with MG132 and 392 compounds from a cancer compound library (Extended-Data Fig. 7). A summary of the experimental and analytical details can be found in Supplementary Information Table 3. The list of compounds can be found in Supplementary Information Table 4. The screen results and the numerical data can be found in Supplementary Information Table 5 and 6. Among the compounds that enhanced foci formation were a number of proteasome and HSP90 inhibitors. Notably, of nine topoisomerase inhibitors (type 1 and 2) in the library, six prevented foci formation.

High Content Imaging Screen Setup

The chemical screen for HSF1 foci modifiers was conducted in collaboration with the Swanson Biotechnology High Throughput Sciences (HTS) Facility at the Koch Institute (KI), MIT. The MG132 addition, compound library pinning, cell incubation, cell fixation, nuclear staining and washing steps were performed at the KI HTS facility. The imaging was performed at the Laboratory for System Pharmacology (LSP), Harvard Medical School. Image analysis was performed by GG with a custom MATLAB pipeline freely available (image analysis details are included in a dedicated section of the Methods).

Compound library information

The Selleck Cambridge Cancer Library was provided and screened by the KI HTS Facility. The complete list of compounds is available in Supplementary Information Table 4. All compounds were used at single dose, final concentration of 10 μM. A total of 392 compounds were arrayed in 96-well plates, 80 compounds per plate and were tested in duplicate assay plates. Each plate contained 8 negative control DMSO wells. One plate was not treated with MG132 and used as positive control (no stress). Drugs were added to cell assay plates using a 250 nl pin transfer tool (V&P Scientific) mounted on the MCA96 head of a Freedom Evo 150 (Tecan) liquid handler. Cell staining was performed using a Biotek EL406 plate washer.

Experimental protocol

U2OS pUbC-HSF1-mEGFP cells were plated in 96-well glass bottom plates (Brooks Automation Inc. 96 Well Glass Bottom Black Plates MGB09612LGL). Cells were seeded at approximate density of 3,000 cells per well two days prior to treatment. The following protocol was performed on 11 plates total:

aspirate media

add 250 μL RPMI 1640 media with MG132 2.5 μM (one control plate was not treated with MG132)

transfer 250 nL of drugs at a stock concentration of 10 mM (1:1000 dilution, final assay concentration of 10 μM)

incubate for 3 hours at 37°C 5% CO2 incubator

aspirate media

add 50 μL of 2% paraformaldehyde in 1X PBS and incubate for 15 minutes at room temperature

add 300 μL PBS 1X

aspirate and add 300 μL PBS 1X

add 33 μL Hoechst-33342 at 60 ng/μL (5.55 ng/μL final concentration) and incubate for 10 minutes at room temperature

aspirate and add 300 μL PBS 1X

store at 4°C

Image Acquisition

Plates were imaged using, DAPI and FITC channels on the GE IN Cell Analyzer 6000 imaging system with a 20X 0.75 NA Plan Apo objective. For each well 36 non-overlapping fields of view were imaged (100 μm distance).

Data Analysis

For each well from the screen we obtained between 2,500 and 8,000 single-cell observations. The following measurements were extracted for each single cell: Nuclear Area, Solidity, DNA Content, Total HSF1 FAU, HSF1-FI.

From the single-cell distributions for each well (ie each compound replicate) we extracted the following summary statistics (presented in Table S3):

Cell Count, number of cells in each well,

Mean and Standard Deviation of Nuclear Area,

Mean and Standard Deviation of DNA Content,

Mean and Standard Deviation of Total HSF1,

Mean and Standard Deviation of HSF1-FI,

Plate Normalized HSF1-FI, Focus Index normalized by the mean of the negative controls in the specific compound plate (this normalizes plate-to-plate difference in detection and analysis),

-

SSMD, sample estimation of the Strictly Standardized Mean Difference, calculated with the following formula: ( Xi-<XNeg>) / (sN (2*(nN-1)/K)1/2)), where

Xi = sample mean HSF1-FI;

XNeg = sample mean HSF1-FI for negative control wells in plate (ie DMSO treated);

sN = sample standard deviation HSF1-FI for negative control wells in plate;

nN = number of negative control wells in plate;

K = nN – 2.48;

p-value, from two-sample t-test from ttest2.m function in Matlab comparing 2 sample wells to control wells from the same plate.

These statistics are included in Supplementary Information Table 5 and 6.

Results

The compound library included compounds shown to have anti-cancer activity independent of the pathway. It encompasses inhibitors of DNA/RNA synthesis (10), mTOR (10), HDAC (9), PI3K (8), JAK (7), CDK (7), Topoisomerase I (3), Topoisomerase II (6), Proteasome (4), Hsp90 (2) and a number other fundamental cellular pathways.

We found two classes of compounds for which multiple compounds were found as significant modifiers of HSF1 foci formation (Extended-Data Figure 7):

proteotoxic stressors significantly increased the mean HSF1-FI

topoisomerase inhibitors significantly decreased the mean HSF1-FI

Proteotoxic stressors increase the activation of HSF1. In Fig.2b we show that the amount of foci formation increases with stress severity. Hence increasing the burden of proteotoxic stress is expected to lead to higher HSF1-FI.

The topoisomerase I and II inhibitors act via two main mechanisms of action: catalytical inhibition of enzyme function (Apicidin, Irinotecan and Etoposide) and DNA interaction (all others tested). The DNA intercalators were all able to significantly reduce the formation of foci, while the others did not have any effect. Most topoisomerase inhibitors are highly toxic to cells, so we opted to conduct follow up experiments using mitoxantrone, a less powerful inhibitor of HSF1 foci (still found as significant in the screen, p ~ 0.003) but less toxic to cells.

Code availability

MATLAB codes used to perform the t-CyCIF and live cell image analysis are available on GitHub: https://github.com/santagatalab. Live cell tracking was performed using the p53cinema MATLAB GUI (GitHub: https://github.com/balvahal/p53CinemaManual). The repositories are public, and the codes are freely downloadable from the GitHub website. Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Sandro Santagata (ssantagata@bics.bwh.harvard.edu).

Statistics Reporting and Reproducibility

All statistical analysis was performed in Matlab software (Mathworks). Data are plotted as mean ± standard error (s.e.m.), unless specified otherwise in Figures 1d and 4j. Statistical testing was performed using non-parametric Kolmogorov-Smirnov two-sided test with P = 0.05 as significance threshold. Multiple hypothesis testing correction was not indicated and not applied. The sample distributions were estimated with a kernel-density estimation function. In each figure legend, the range of number (n) of either image-analysis segmented objects, single cells, patient samples or biological repeats included in the final statistical analysis is indicated. Results was replicated in independent experiments at least 3 times or in 3 independent patient samples, whenever available; the exact number of the sample sizes can be found in the Source Data excel files included – sheet name “Statistics and Reproducibility”.

Data availability

The numerical data are available through the Synapse SAGE Bionetworks portal www.synapse.org (Synapse ID: syn20505972; DOI: http://doi.org/10.7303/syn20505972). Chemical screen results have been deposited in the NCBI PubChem Bioassay database, Assay ID (AID) 1347162; https://pubchem.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/bioassay/1347162. All other data supporting the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Extended Data

Extended Data Fig. 1.

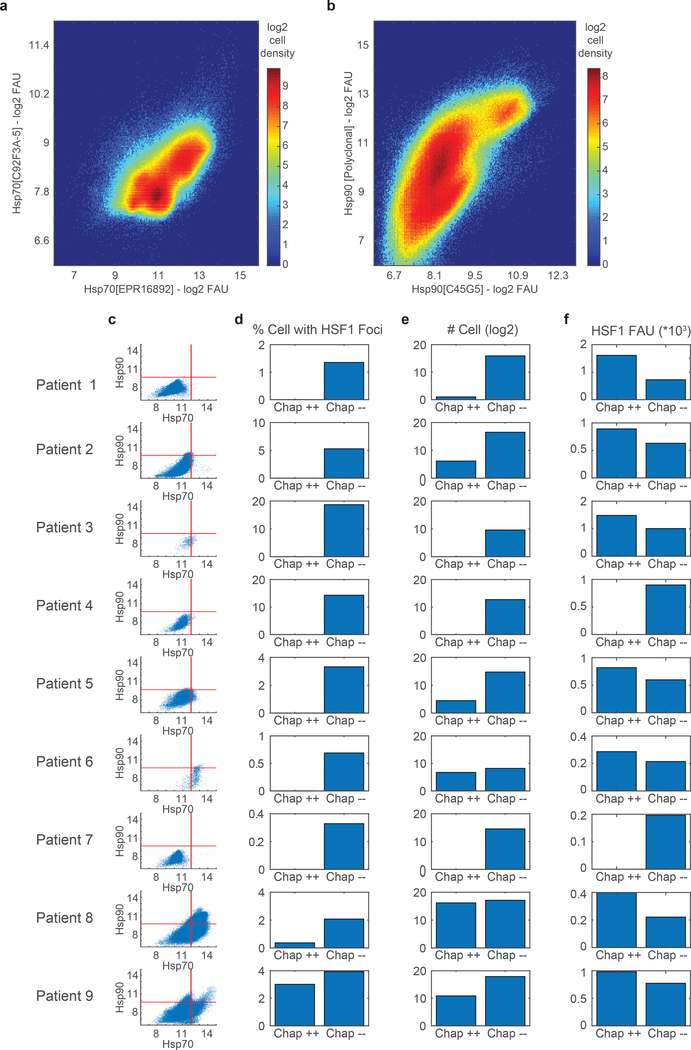

HSF1 foci quantification in colon adenocarcinoma tissues a-b. Composite images of immunofluorescence data of HSF1 (clone 10H8, green) and DAPI nuclear stain (blue) from a tissue sections of colon adenocarcinoma with adjacent non-neoplastic colon tissue. T, tumor; N, normal. a. Insets are two regions at the borders between tumor and normal tissue. b. Insets 1–3 tumor tissue, inset 4 normal colon tissue. c. High power composite image of t-CyCIF data showing CDX2 (red), αSMA (purple) CD45 (yellow). d. Quantification of t-CyCIF data from three colon adenocarcinoma whole tissue sections indicating the lineage of cells positive for HSF1 foci (“Foci+”, HSF1-FI > 0.05). e. Bar graph of Foci+ cells in colon adenocarcinoma cases (n = 93 patients; from tissue microarray (TMA); four cores per patient, average +/− SEM) from t-CyCIF data. f. Scatter plot of the frequency of Foci+ cells in tumor versus non-tumor compartments (CD45+ immune cells, yellow; αSMA+ stromal cells, purple). Each dot represents CD45 or αSMA data from a single core from TMA. g. Bar graph of Foci+ cells from t-CyCIF data from TMA (tumor, red; immune, yellow; stroma, purple, n = 87 patients, average + SEM). h. 2D single-cell, spatially-averaged heatmap of t-CyCIF data of HSP70 and HSP90 expression normalized over median expression (scalebar 1mm). i. Kernel density (KD) estimated frequency distribution plot of HSP70 chaperone protein expression in normal colon tissue (red) and adenocarcinoma tissue (blue) from t-CyCIF. j. Top, 2D density plot of HSF1 concentration versus chaperone proteins from t-CyCIF of colon adenocarcinoma in Figure 1b,c (n ~ 250,000 cells). Bottom, corresponding scatter plot (subsampling of 1,000 cells, one dot per cell; dashed line, linear fit). k. Scatter plot of mean HSF1-FI versus mean chaperone levels of the TMA (one dot per core; color represents the number of cells in core). Source data are provided in Source Data Extended Data Figure 1.

Extended Data Fig. 2.

HSF1 foci quantification in myeloma/plasmacytoma tissues a-b. 2D cell density plots of two antibodies against Hsp70 (a) and Hsp90 (b) protein from 9 patient samples of plasmacytoma/myeloma from Figure 1e–k. c-f. Statistics for each of the 9 plasmacytoma/myeloma patient samples. c. Single-cell scatter plot of signal from Hsp70 EPR16892 antibody versus Hsp90 C45G5 antibody. Red lines represent the threshold identified in Figure 1 for which cells were considered positive or negative for the corresponding chaperone protein expression. d. percentage of cells with HSF1 foci (HSF1-FI > 0.05) divided by cells positive or negative for both HSP70 and HSP90 chaperones (“Chap++” and “Chap--” respectively). e. Number of cells in each Chap++ and Chap-- category. f. Mean HSF1 levels per chaperone category. Source data are provided in Source Data Extended Data Figure 2.

Extended Data Fig. 3.

Time-lapse microscopy of tagged HSF1 in tissue culture cell lines a. Western blot on U2OS cell lines expressing fluorescent protein tagged HSF1. Lanes: 1) U2OS, 2) U2OS HSF1-mVenus, 3) U2OS HSF1-mEGFP, 4) U2OS HSF1-mTQ2, 5) U2OS HSF1Δp-mTQ2, 6)-7) U2OS HSF1-mVenus FKBP-cHSF1-mTQ2,6) no Shield-1, 7) 500nM Shield-1 for 24 hours. Top part of membrane, anti-HSF1 monoclonal antibody. Bottom part of membrane, anti-GAPDH antibody (see Source Data Extended Data Figure 3 for unprocessed blot image). b. Quantification of bands in lanes 2–4 from western blot image in a (see Methods for Quantification details). c. Left, kernel density estimate (KD) pdf of HSF1 antibody signal level in cells from 9 plasmacytoma/myeloma patient samples from Figure 1e–k (total of n ~ 2*106 cells). Right, KD pdf of HSF1 antibody level in U2OS (blue) and U2OS HSF1-mVenus cells (orange), n ~ 17,000 and 20,000 cells. d. Fold induction of HSPA1B, HSPA6, and HSP90AA1. Real-time PCR from bulk cell populations in U2OS, U2OS HSF1-mEGFP 3 hours post MG132 2.5uM (bars are biological replicates). e-f. Time-lapse microscopy of U2OS HSF1-mVenus cells treated with 42ºC temperature (scalebar = 10 μm) and quantification (n ~ 16,000–24,000 cells, median + 75th percentile, see Source Data Extended Data Figure 3 for exact cell numbers and single cell data). f. Single-cell HSF1-FI quantification. g. Dynamics of the percentage of cells with foci after proteotoxic stressor addition (U2OS HSF1-mVenus cells, live cell time lapse microscopy, 30 minutes intervals, n ~ 260 cells, see Source Data Extended Data Figure 3), using three different thresholds to HSF1-FI to define the foci positivity, 0.025, 0.05 and 0.1. h. Fold induction of HSP70 genes (HSPA1B, HSPA6) and HSP90AA1 using real-time PCR from bulk cell populations after gradient doses of MG132 and STA9090 (MG132: 5, 2.5, 1.25, 0.625 μM; STA9090: 50, 25, 12.5, 6.25 nM). Statistics and Source Data are provided in Source Data Extended Data Figure 3.

Extended Data Fig. 4.

Relationship between HSF1 foci and HSF1 transcriptional activity a. Time-lapse heatmaps for HSF1-FI and HSP70 Transcriptional Reporter (TR) induction dTR/dt time derivative (one cell per row, n=152 cells). Black line, entry time of HSF1-FI < 0.2 b. Scatter plot of HSF1-FI versus dTR/dt from all instances from panel a (n=3,400 cell measurements, red line = linear fit). c-d. Scatter plot of TR versus (c.) time-integrated and (d.) maximum HSF1-FI 6 hours post 50nM STA9090 (Pearson correlation, bootstrapping p-values). e. Single-cell trace examples of time relationship between HSF1-FI and TR. Each dot represents a single-cell measurement, the color represents the time post STA9090 50nM addition (starting 2 hours). Blue lines, linear fit y = α*x + β. f. Bootstrapping on parameter “α” in fits from panel e. Blue line, KD pdf of the α parameters from cells with R2>0.5. The matching between foci time dynamics and transcriptional reporter (TR) induction were randomly permuted 1,000 times. Red line, mean distribution of the α parameters for the permuted traces over all 1,000 permutations (light red area, 25th to 75th percentile). g. HSPA1A RNA FISH time course on U2OS HSF1-mEGFP cells post 100 nM STA9090 (n > 2200 cells per sample, see Source Data Extended Data Figure 4 for statistics details). h. RNA FISH for HSPA1A on HCT15 HSF1-mVenus cells and U2OS HSF1-mEGFP cells after proteasome inhibition (Bortezomib 100 nM, 4 hours post). i-j. Immunofluorescence on U2OS HSF1-GFP cells (HSF1 green, HSP70 red, clone C92F3A-5). 1 μM MG132 overnight treatment. scalebar = 10 μm and j. quantification. Yellow, HSF1-FI<0.01, n = 1430 cells. Red, 0.01 < HSF1-FI < 0.2, n = 1156 cells. Blue HSF1-FI > 0.2, n = 492 cells. Inset, KD estimated distributions (two-sided KS p-values: high vs medium focied cells, p~10−41, medium vs low focied cells, p~10−18). Source data are provided in Source Data Extended Data Figure 4.

Extended Data Fig. 5.

Relationship between HSF1 foci and cell death by time-lapse microscopy a. Time-lapse microscopy traces of HSF1-GFP cell concentration from single cells followed for 12 hours at 30-minute intervals post 2.5 μM MG132 (mean +/− SEM). Cells are separated between those that survived (blue, n = 96 cells) and those that died (red, n = 54 cells) as in Figure 3a. b-c. Bar graph of HSF1-FI (b) and HSF1 concentration (c) at 5 and 10 hours after 2.5 μM MG132 comparing cells that survive (blue) and cells that die (red) during the time lapse microscopy experiment in panel a. and Figure 3a (two-sided KS p-value with 0.05 significance threshold, mean +/− SEM). d. Immunofluorescence on U2OS cells with mVenus protein endogenously inserted in C-terminus of HSF1 genomic locus (HSF1-mVenusKI). Two independent clones (called “B12” and “C5”) were analyzed. Scalebar = 10 μm. e. Quantification of time-lapse microscopy on U2OS HSF1-mVenusKI clone B12 and C5 after 5 μM MG132. Red = cells that died during the 14 hours experiment (n = 153 cells and n = 156 cells), green = cells that survived (n = 101 cells and n = 199 cells, mean +/− SEM). Source Data are provided in Source Data Extended Data Figure 5.

Extended Data Fig. 6.

Relationship between HSF1 foci and cell death a. Quantification of single-cell time-lapse microscopy on U2OS cHSF1-CFP after induction with 250 nM Shield-1. Upper panels, HSF1 Focus Index (HSF1-FI). Lower panels, total cHSF1 induction. Cell are divided between levels of total cHSF1 induction, on the left are cells with low induction level and on the right are cells with high induction levels. Red = cells that died during the 29 hours experiment n = 12 cells and n = 14 cells, green = cells that survived n = 182 cells and n = 27 cells (two-sided KS p-value with 0.05 significance threshold, 20-minute intervals, mean +/− SEM). b. BIM peptide titration on cells treated with 1.2 μM MG132. Cells increasingly lost more cytochrome c. Full cell distribution (yellow line) is divided into cells that released cytochrome c (“dying cells”, red dashed distribution) and cells that had not released cytochrome c (“healthy cells”, dashed blue line distribution). Histograms show the distribution of HSF1-FI in healthy (left column) and dying cells (right column). Across BIM concentrations, the foci levels in dying cells is higher than in healthy cells. Source Data are provided in Source Data Extended Data Figure 6.

Extended Data Fig. 7.

Small molecule imaging-based screen for HSF1 foci modifiers a. Summary scatter of Selleck Cambridge Cancer Library high content imaging screening results for changes in HSF1 foci. Each dot is a compound out of total of 392 compounds. Each compound was tested in duplicated wells each imaged in 36 non-overlapping fields. Total cell count per compound well varied between 2000 and 8000 cells (see Supplementary Information Table 3, 4 and 5 for compound details and full results). Compounds of interest (red dots) are either proteotoxic compounds or topoisomerase inhibitors. b. Zoomed in scatter of grey shaded area in a. c. Sample images from high content imaging screen (full single field displayed from one of two replicated wells, scalebar = 10 μm).

Extended Data Fig. 8.

High resolution 3-dimensional reconstruction of HSF1 foci in fixed cells a-f. Single cells statistics from U2OS HSF1-mEGFP cells fixed with paraformaldehyde at 6 time points from 0 to 8 hours after the addition of 2.5 μM MG132. Z-stacked images were deconvolved and both cells and HSF1 segmented. a. Deconvolved images of U2OS HSF1-mEGFP cell from z-stack imaging. Top row, x-y 2D view. Second row, 3-dimensional view of single cells with surface rendering in Imaris and their overlay (2 μm scalebar). A total of 377 cells analyzed. b. Histogram of cube root of foci volume for all foci in experiment from panel a (n = 3850 foci total). Color lines represent the 3-component Gaussian mixture model fitting of the histogram (green line global fit, orange, yellow and purple single component fits weighted by component contribution). The black lines represent the threshold identified by the GMM and used to separate foci between small (< 136 voxels) medium (between 136 and 592 voxels) and large foci (> 592 voxels). c-f. Single cells statistics. c-e. Blue, one dot per cell, n = 44, 67, 65, 44, 77 and 77 cells. Black, mean +/− SD. c. Total GFP signal. d. Nucleus area. e. Mean foci volume for all foci independent of size (n = 10, 2092, 2589, 1684, 2410, 2334 foci per time point, mean +/− SEM). f. Mean fluorescent signal of HSF1 foci subdivided by volume in large (red), medium (green) and small (blue) foci (mean +/− 25th percentile). Source data are provided in Source Data Extended Data Fig. 8.

Extended Data Fig. 9.

Tagged HSF1 FRAP traces and statistics a-d. Fluorescent recovery after photobleaching (FRAP) single-cell traces and exponential fits. Region of interest photobleached after 5 seconds from start of imaging. a-b. Whole focus FRAP traces after 2.5 μM MG132 treatment. a. 2 hours after treatment. b. 8 hours after treatment. c-d. Half-focus FRAP traces after 2.5 μM MG132 treatment. c. 1.5 hours after treatment. d. 8 hours after treatment. e. Whole focus FRAP Thalf recovery time estimates after 2.5 μM MG132 addition (mean +/− SEM, n = 28, 17, 27, 19, 19, 10 foci per time point). f-g. Whole focus FRAP on HCT15 HSF1-YFP parameter estimates 1.5 and 5 hours after 5 μM MG132 treatment. f. Immobile fraction and g. Thalf recovery time (n = 14 foci, two-sided KS p-value). h. Half-focus FRAP Thalf recovery time estimates 1.5 and 8 hours after the addition of 2.5 μM MG132 (mean +/− SEM, n = 30 and 32 foci per time point, two-sided KS p-value). Source Data are provided in Source Data Extended Data Figure 9.

Extended Data Fig. 10.

Further characterization of HSF1 foci solubility a-b. Sample images of time-lapse microscopy of U2OS HSF1-GFP cells after 10% 1,6-hexandiol addition (images acquired at 20 second intervals; cells were pre-stressed with 10 μM MG132) A total of 188 cells was imaged and analyzed. a. Example of cells in which most of the HSF1 foci burden rapidly dissolved after the addition of 1,6-hexandiol. The timescale of dissolution (20–30 seconds) is an order of magnitude faster than the timescale of cell membrane permeabilization (200–300 seconds). 1,6-hexanediol was applied one hour after addition of MG132 when most foci were liquid condensates (scalebar = 10 μm). b. Examples of cells showing that HSF1 foci are still visible after cell membrane permeabilization had occurred due to the addition of 1,6-hexandiol, which was applied eight hours after addition of MG132 when many foci were enlarged granular aggregates. See Figure 4 for quantification and statistics and Source Data Extended Data Figure 10 for details on cell numbers (scalebar = 10 μm). c. Fold induction of HSP90AA1 and inducible HSP70 genes (HSPA1B, HSPA6) using quantitative PCR from bulk cell populations after gradient doses of MG132 (2.5, 1.25, 0.62, 0.31 μM, median and standard deviation of 4 technical replicates). Blue bars = U2OS HSF1 wild type. Green bars = U2OS HSF1Δp mutant (both tagged with CFP). Source Data are provided in Source Data Extended Data Figure 10.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This work was supported by NIH grants R01-CA194005 (SS), U54-CA225088 (PKS, SS), R00-CA188679 (KS) and T32HL007627 (GG), the Ludwig Center at Harvard (PKS, SS) and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health Dean’s Fund for Scientific Advancement (K.S.). This work was supported in part by the Koch Institute Support Grant P30-CA14051 and the Dana-Farber/Harvard Cancer Center Support Grant # P30-CA06516 from the National Cancer Institute. We thank J Lin, J Muhlich for help with CyCIF imaging and analysis, D Landgraft, M Shoulders and G Lahav for providing reagents and S Alberti for helpful discussions. We thank the Koch Institute Swanson Biotechnology Center for technical support, specifically Jaime H. Cheah and Christian K. Soule in the High Throughput Sciences Facility and the Confocal Microscopy Core at Brigham and Women’s Hospital.

Footnotes

Competing Interests Statement

PKS is a member of the Scientific Advisory Board of RareCyte Inc.. PKS is also co-founder of Glencoe Software, which contributes to and supports the open-source OME/OMERO image informatics software used in this paper. S.S. is a consultant for RareCyte, Inc.. Other authors have no competing financial interests to disclose.

REFERENCES

- 1.Lindquist S The heat-shock response. Annu. Rev. Biochem 55, 1151–1191 (1986). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Vihervaara A & Sistonen L HSF1 at a glance. J. Cell. Sci 127, 261–266 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Sarge KD, Murphy SP & Morimoto RI Activation of heat shock gene transcription by heat shock factor 1 involves oligomerization, acquisition of DNA-binding activity, and nuclear localization and can occur in the absence of stress. Mol. Cell. Biol 13, 1392–1407 (1993). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cotto J, Fox S & Morimoto R HSF1 granules: a novel stress-induced nuclear compartment of human cells. J. Cell. Sci 110 (Pt 23), 2925–2934 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jolly C, Morimoto R, Robert-Nicoud M & Vourc’h C HSF1 transcription factor concentrates in nuclear foci during heat shock: relationship with transcription sites. J. Cell. Sci 110 (Pt 23), 2935–2941 (1997). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jolly C, Usson Y & Morimoto RI Rapid and reversible relocalization of heat shock factor 1 within seconds to nuclear stress granules. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 96, 6769–6774 (1999). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nonaka T, Akimoto T, Mitsuhashi N, Tamaki Y & Nakano T Changes in the number of HSF1 positive granules in the nucleus reflects heat shock semiquantitatively. Cancer Lett. 202, 89–100 (2003). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Au Q, Kanchanastit P, Barber JR, Ng SC & Zhang B High-content image-based screening for small-molecule chaperone amplifiers in heat shock. J Biomol Screen 13, 953–959 (2008). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Biamonti G & Vourc’h C Nuclear stress bodies. Cold Spring Harb Perspect Biol 2, a000695 (2010). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Chowdhary S, Kainth AS, Pincus D & Gross DS Heat Shock Factor 1 Drives Intergenic Association of Its Target Gene Loci upon Heat Shock. Cell Rep 26, 18–28.e5 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Li J, Labbadia J & Morimoto RI Rethinking HSF1 in Stress, Development, and Organismal Health. Trends Cell Biol. 27, 895–905 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Anckar J & Sistonen L Regulation of HSF1 function in the heat stress response: implications in aging and disease. Annu. Rev. Biochem 80, 1089–1115 (2011). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Metz A, Soret J, Vourc’h C, Tazi J & Jolly C A key role for stress-induced satellite III transcripts in the relocalization of splicing factors into nuclear stress granules. J. Cell. Sci 117, 4551–4558 (2004). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Rizzi N et al. Transcriptional activation of a constitutive heterochromatic domain of the human genome in response to heat shock. Mol. Biol. Cell 15, 543–551 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Jolly C et al. In vivo binding of active heat shock transcription factor 1 to human chromosome 9 heterochromatin during stress. J. Cell Biol 156, 775–781 (2002). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jolly C et al. Stress-induced transcription of satellite III repeats. J. Cell Biol 164, 25–33 (2004). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Eymery A, Souchier C, Vourc’h C & Jolly C Heat shock factor 1 binds to and transcribes satellite II and III sequences at several pericentromeric regions in heat-shocked cells. Exp. Cell Res 316, 1845–1855 (2010). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holmberg CI, Illman SA, Kallio M, Mikhailov A & Sistonen L Formation of nuclear HSF1 granules varies depending on stress stimuli. Cell Stress Chaperones 5, 219–228 (2000). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lin J-R et al. Highly multiplexed immunofluorescence imaging of human tissues and tumors using t-CyCIF and conventional optical microscopes. Elife 7, (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Du Z et al. Qualifying antibodies for image-based immune profiling and multiplexed tissue imaging. Nat Protoc 14, 2900–2930 (2019). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Calderwood SK & Gong J Heat Shock Proteins Promote Cancer: It’s a Protection Racket. Trends Biochem. Sci 41, 311–323 (2016). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Banaszynski LA, Chen L-C, Maynard-Smith LA, Ooi AGL & Wandless TJ A rapid, reversible, and tunable method to regulate protein function in living cells using synthetic small molecules. Cell 126, 995–1004 (2006). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Zuo J, Baler R, Dahl G & Voellmy R Activation of the DNA-binding ability of human heat shock transcription factor 1 may involve the transition from an intramolecular to an intermolecular triple-stranded coiled-coil structure. Mol. Cell. Biol 14, 7557–7568 (1994). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Deng J et al. BH3 profiling identifies three distinct classes of apoptotic blocks to predict response to ABT-737 and conventional chemotherapeutic agents. Cancer Cell 12, 171–185 (2007). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Mateju D et al. An aberrant phase transition of stress granules triggered by misfolded protein and prevented by chaperone function. EMBO J. 36, 1669–1687 (2017). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kroschwald S, Maharana S & Simon A Hexanediol: a chemical probe to investigate the material properties of membrane-less compartments. Matters 3, e201702000010 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang J et al. A Molecular Grammar Governing the Driving Forces for Phase Separation of Prion-like RNA Binding Proteins. Cell 174, 688–699.e16 (2018). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Neudegger T, Verghese J, Hayer-Hartl M, Hartl FU & Bracher A Structure of human heat-shock transcription factor 1 in complex with DNA. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol 23, 140–146 (2016). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guettouche T, Boellmann F, Lane WS & Voellmy R Analysis of phosphorylation of human heat shock factor 1 in cells experiencing a stress. BMC Biochem 6, 4 (2005). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Budzyński MA, Puustinen MC, Joutsen J & Sistonen L Uncoupling Stress-Inducible Phosphorylation of Heat Shock Factor 1 from Its Activation. Mol. Cell. Biol 35, 2530–2540 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Santagata S et al. High levels of nuclear heat-shock factor 1 (HSF1) are associated with poor prognosis in breast cancer. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 108, 18378–18383 (2011). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mendillo ML et al. HSF1 drives a transcriptional program distinct from heat shock to support highly malignant human cancers. Cell 150, 549–562 (2012). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Hyman AA, Weber CA & Jülicher F Liquid-liquid phase separation in biology. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol 30, 39–58 (2014). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]