Abstract

Background

Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) sexual and gender minorities (SGM) face unique challenges in mental health and accessing high-quality healthcare.

Objective

To identify barriers and facilitators for shared decision making (SDM) between AAPI SGM and providers, especially surrounding mental health.

Research Design

Interviews, focus groups, and surveys.

Subjects

AAPI SGM interviewees in Chicago (n=20) and San Francisco (n=20). Two focus groups (n=10) in San Francisco.

Measures

Participants were asked open-ended questions about their healthcare experiences and how their identities impacted these encounters. Follow-up probes explored SDM and mental health. Participants were also surveyed about attitudes towards SGM disclosure and preferences about providers. Transcripts were analyzed for themes and a conceptual model was developed.

Results

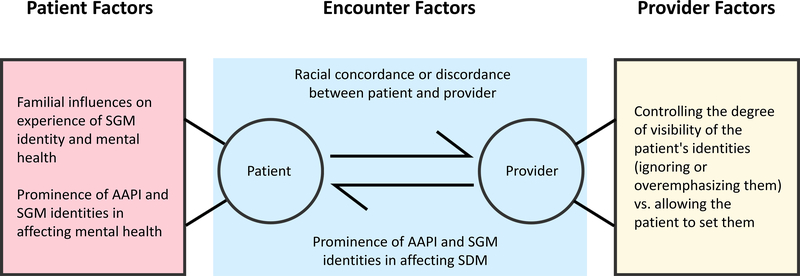

Our conceptual model elucidates the patient, provider, and encounter-centered factors that feed into SDM for AAPI SGM. Some participants shared the stigma of SGM identities and mental health in their AAPI families. Their AAPI and SGM identities were intertwined in affecting mental health. Some providers inappropriately controlled the visibility of the patient’s identities, ignoring or overemphasizing them. Participants varied on whether they preferred a provider of the same race, and how prominently their AAPI and/or SGM identities affected SDM.

Conclusions

Providers should understand identity-specific challenges for AAPI SGM to engage in SDM. Providers should self-educate about AAPI and SGM history and intracommunity heterogeneity before the encounter, create a safe environment conducive to patient disclosure of SGM identity, and ask questions about patient priorities for the visit, pronouns, and mental health.

Keywords: Sexual and Gender Minorities (SGM); Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ); Asian American and Pacific Islander (AAPI); shared decision making (SDM); mental health

INTRODUCTION

Asian American Pacific Islanders (AAPI) who are also sexual and gender minorities (SGM) experience compounded minority stress. 1,2 Minority stress causes mental health problems such as internalized homophobia, expectations of rejection, and poor coping mechanisms as a result of stigma, prejudice, and discrimination. 3 Mental health problems such as suicidality, depression, anxiety, substance misuse, and shame have been well-documented for both AAPI and SGM communities. 1,4–8 However, little research has analyzed the unique mental health needs of AAPI SGM individuals. These intersectional needs require understanding of how composite identities impact an individual, rather than each identity (race vs. gender vs. sexual orientation) independently. 9,10

Shared decision making (SDM) with AAPI SGM promises to be a critical tool for improving mental health.11 SDM is a model of patient-provider communication that has three domains: (1) information-sharing, (2) deliberation, and (3) decision making. 12 SDM improves chronic health outcomes such as diabetes and hypertension, but is underutilized with racial/ethnic minority patients. 13–19 In SDM, both provider and patient bring their own myriad identities, life experiences, health literacy, and power/status to the encounter, with varying levels of discordance.12 Adverse provider-patient interactions can worsen health outcomes, and conversely, strong communication and SDM can improve health outcomes and quality of care. Previous studies have not explored specific barriers and facilitators to effective SDM with AAPI SGM individuals.

We conducted interviews and focus groups with AAPI SGM to identify barriers and facilitators to effective SDM, particularly regarding mental health decisions, and developed a model highlighting patient, provider, and encounter-centered factors impacting SDM. We provide practical recommendations for providers who care for this patient population. Our hope is that increasing provider awareness and education about AAPI SGM will improve communication and reduce inequities in care and outcomes, especially surrounding mental health.

METHODS

Overview

In-person, semi-structured, in-depth interviews and focus groups were conducted with 50 people who identified both as Asian American/Pacific Islander and SGM. Twenty of these interviews occurred in Chicago; 20 interviews and two focus groups (10 participants total) occurred in San Francisco.

Audio recordings were transcribed and a codebook was iteratively developed by team members reading transcripts for themes. The transcripts were coded using NVivo 11. After individual themes were identified and explored, an overarching model of factors affecting SDM for AAPI SGM patients was developed. This study was approved by the [Blinded] Institutional Review Board. Further methodological details based on the COnsolidated criteria for REporting Qualitative research (COREQ) are included in the appendix.

Eligibility Criteria and Recruitment of Participants

Recruitment occurred through purposive sampling without particular quotas for subpopulations.

Eligible individuals self-identified as AAPI, and were either men who have sex with men (MSM), men who have sex with both men and women (MSMW), women who have sex with women (WSW), women who have sex with men and women (WSWM), and/or identified as lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, or genderqueer. The Morten Group, a national consulting firm, recruited individuals in Chicago. In San Francisco, the Asian and Pacific Islander (API) Wellness Center, a community health and social services center that particularly serves the API SGM community, recruited AAPI individuals who were MSM, MSMW, gay or bisexual men, transgender, or genderqueer.

Data Collection

Interviews and focus groups were conducted in community or healthcare organizations from February 2016 – June 2017. Participants were asked open-ended questions about their healthcare experiences and how their identities impacted these encounters. Follow-up probes explored SDM and mental health. The interview guide was informed by our prior research,20 literature review, expert opinion, and community forums with SGM of color. Interviewers who identified as AAPI SGM were utilized to increase empathy, trust, comfort, and honesty within the interview. Interviews were audio recorded. Participants also completed a paper survey about healthcare utilization, perceptions of the healthcare setting, communication with providers, discrimination, experiences with and preferences for SDM, health behavior and status, and demographic information. “Health care providers” were defined as “doctors, nurse practitioners, physician assistants, psychologists, counselors, etc.” All participants received $40 as compensation, and focus group participants also received refreshments.

Data Analysis

Audio recordings of these interviews and focus groups were transcribed. The codebook was initially developed from questions and themes in the interview guide. The first 10 transcripts were coded by [blinded] and the codebook was amended iteratively to consensus to establish inter-coder reliability.

The remaining transcripts were each randomly assigned to two coders of the team (blinded). Repeat pairings of coders together was minimized to reduce coder bias. Team members coded the transcripts individually, then met in pairs to discuss until consensus. Final codes and transcripts were uploaded to NVivo 11. The team conducted secondary analysis inductively to identify major themes and recommendations for clinicians based upon these themes and quotations from the subjects. The team also developed a conceptual model for SDM between clinicians and AAPI SGM persons, building upon the model of Peek et al.12 We identified actionable recommendations for clinicians from both direct recommendations for providers from the participants as well as our own inductions from participant quotations.

RESULTS

Participants

Table 1 depicts participant characteristics, including racial/ethnic, gender, and sexual identities. Table 2 shows participants’ healthcare utilization, attitudes about LGBTQ disclosure, and preferences for providers.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics (N = 50)1

| n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Race/ethnicity | Asian/Asian American, not otherwise specified2 | 22 (44) |

| Chinese/Chinese American | 5 (10) | |

| Filipino/Filipino American | 6 (12) | |

| Multiracial/Multiethnic | 12 (24) | |

| Pacific Islander | 2 (4) | |

| Other | 3 (6) | |

| Gender3 | Cis man | 37 (74) |

| Cis woman | 3 (6) | |

| Gender non-conforming/Other4 | 4 (8) | |

| Trans man | 4 (8) | |

| Trans woman | 1 (2) | |

| Two-spirited | 1 (2) | |

| Asexual | 1 (2) | |

| Bisexual | 5 (10) | |

| Sexual orientation | Gay | 27 (54) |

| Queer5 | 16 (32) | |

| No labels | 1 (2) | |

| Educational attainment | Some college or 2-year degree | 11 (22) |

| 4-year college graduate | 28 (56) | |

| More than 4-year college | 7 (14) | |

| Missing | 4 (8) | |

| Employment status* | Employed full-time | 28 (56) |

| Employed part-time | 7 (14) | |

| Student | 8 (16) | |

| Unable to work/not employed | 7 (14) | |

| Missing | 4 (8) | |

| Annual individual income | <$10,000 | 7 (14) |

| $10,000-$39,999 | 12 (24) | |

| $40,000-$79,999 | 17 (34) | |

| >$80,000 | 3 (6) |

Totals may be greater than 100% because participants selected more than one response.

Ten focus group participants and two individual interviewees grouped under Asian/Asian American, as there was no further specification.

Cis or cisgender refers to someone whose gender identity matches their sex assigned at birth. Trans or transgender refers to someone whose gender identity does not match their sex assigned at birth. Gender non-conforming or genderqueer or gender non-binary refers to those who identify as neither a man or woman. Two-spirited is an indigenous term referring to having both a masculine and feminine spirit.24 Transmasculine refers to someone who was assigned female at birth and identifies as more masculine than feminine. Transfeminine refers to someone who was assigned male at birth and identifies as more feminine than masculine.

One participant identified as female/nonbinary, one as gender non-conforming, one as genderqueer, and one as genderqueer and transmasculine.

From San Francisco focus group: two identified as “Bisexual, Pansexual, or Queer.”

Table 2.

Healthcare Utilization, Attitudes about Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer (LGBTQ) Disclosure, and Preferences for Providers1

| n (%) | ||

|---|---|---|

| Have regular provider | Yes | 35 (76) |

| No | 11 (24) | |

| Last seen provider2 | In the last six months | 26 (58) |

| In more than the last six months | 19 (42) | |

| Open about being LGBTQ with provider | Strongly agree/agree | 29 (63) |

| Neutral/disagree/strongly disagree | 14 (30) | |

| Don’t know/not applicable | 3 (7) | |

| Hide the fact that I am LGBTQ from provider because of how they react | Strongly agree/agree | 11 (24) |

| Neutral/disagree/strongly disagree | 31 (67) | |

| Don’t know/not applicable | 4 (9) | |

| Feel respected for being LGBTQ by provider | Strongly agree/agree | 22 (48) |

| Neutral/disagree/strongly disagree | 23 (50) | |

| Don’t know/not applicable | 1 (2) | |

| Actively seek out LGBTQ-friendly providers | Strongly agree/agree | 28 (61) |

| Neutral/disagree/strongly disagree | 17 (37) | |

| Don’t know/not applicable | 1 (2) | |

| Actively seek out health care professionals who match my race/ethnicity | Strongly agree/agree | 18 (39) |

| Neutral/disagree/strongly disagree | 28 (61) |

Data were unavailable for four participants.

One additional participant did not answer the survey question for when they last saw their provider.

Patient-centered factors impacting SDM

SGM identity and mental health in an AAPI family

Participants commented on the burden of familial expectations in AAPI cultures, and how providers who were not AAPI at times struggled with understanding this concept.

“The very few times [the provider] ever addressed the family issue, it’s always been like, ‘Why do you care what your family thinks?’…They didn’t really understand or grasp how deep [family’s] influence was. It was always like, I felt, especially in Asian cultures, it’s like family’s a very strong influence in our lives…I was like, ‘[laugh] Do you not get it?’.”

(Asian American gay/queer male)

The same participant explained that the intersection of their identities made them feel as though they were inadequately meeting the expectations of their immigrant parents, and that providers failed to thoroughly explore this issue.

“…Especially with my personal issues, it was a lot [about my] family, with immigrant parents. And then that on top of being queer…I had …very white therapists. And I think, again they were very like tiptoeing around the issue[s] of Asian-ness and sexuality.] Both at the same time…But when I talked to [the therapists] and I was like, ‘I feel like a failure in terms of me and my parents’ expectations,’ they never really got into that. They were just like, ‘Let’s go back to this thing.’”

(Asian American gay/queer male)

Another participant described the conflicting influences of their family and community’s beliefs on deciding a therapeutic regimen. Ultimately, treatment decisions made with their provider accounted for preferences based on both their Filipino and queer identities.

“Initially, when I sought treatment, I sought medication first, before I sought therapy. And I think a lot of that has to do with my Filipino perception – I come from a medical family – that medicine can make you better, and that medicine comes in the form of pills or liquids. And not really understanding that medicine can come in the form of therapy, as well… [The healthcare decisions my provider and I made together] filled my need as a Filipino to be on… this sort of physical medical intervention. And my need to talk things through, which is a lot of what is done in the queer community, by seeing my therapist. So having those dual processes happening was helpful …When I was an activist on the streets, I no longer wanted to be on medication, because I didn’t want to deal with that in case I ever got arrested. And so my queer community was very supportive of that decision, and really gave me the strength to find alternative means…that didn’t involve medication.”

(Filipino queer male)

Prominence of AAPI and SGM identities in affecting mental health

AAPI and SGM identities were often intertwined, sometimes compounding negative effects of dual minority statuses. For instance, one participant stated:

“A lot of my mental health issues stem from me being queer but in a Filipino family.”

(Mixed race queer male)

Another participant recounted how their AAPI father’s rejection of their SGM identity contributed heavily to the onset of depression.

“So when I told my dad I was gay…he was very upset. He wanted me to break up with my boyfriend…because he wasn’t very supportive of my decision to come out, I got into depression. And I told my dad and he took it as a joke. But when I started going to mental health counselors for help, and telling my dad how depressed I really was, he started to grasp the concept of how my mental health was really influenced.”

(Chinese-American gay man)

Provider-centered factors impacting SDM

Provider ignoring patient’s intersectional identities

Even after disclosure, some providers minimized their patients’ identities explicitly. In one case, the provider did not utilize the concepts presented to her by the patient. Instead she suggested that the patient’s issues could be rooted in causes unrelated to identity, which was off-putting to the patient.

“She’ll kind of reroute [issues] back to like it not having to do so much with identity, and having to do more with like, ‘Oh, well, maybe you’re feeling this thing because, you know, this person just wasn’t being that great of a friend to you.’…she won’t use the frameworks that I have come at her with to offer something helpful back to me…she won’t reference me being queer or a person of color or a biracial person to help me understand any of what I’m coming to her with, which is strange.”

(Biracial queer female)

When asked if health care providers talked to them differently about mental health based on their conception of the patient’s racial/ethnic background, gender identity, or sexual orientation, one participant answered:

“In the past, when I’ve not been satisfied with the care I was getting, [providers] never did. It was almost like those identities didn’t exist unless I talked about it. And so then it was a situation where it was up to me to bring it up and to talk about it rather than them recognizing it...I actually don’t think I’ve had an experience where… [my identities have] been taken into account…”

(Asian queer transgender male)

In one case, after being informed about the participant’s pronouns, the provider continued misgendering the patient as if they had not mentioned anything at all. They attributed this to the provider’s probable lack of experience and education surrounding trans patients.

“And I think I did come out…and said like, ‘I use he/him pronouns, or they/them.’…And it just didn’t register. And…the doctor said something about like, ‘As women we need to…’ And it just made me cringe…I remember specifically being like, ‘Why did you say that?’ And it would have been a reasonably understandable thing to say if I hadn’t said anything. But like, I did…I feel like maybe either she didn’t really [know] how to, or know that like, these are things you shouldn’t say, or had just like forgotten? Probably did not have much familiarity with trans patients.”

(Korean/Korean American gay/queer transgender male)

Provider overemphasizing patient’s intersectional identities

While some providers ignored the impact of participants’ identities on their mental health and SDM, other providers inappropriately attributed or overemphasized the role of their identities in their health-related concerns. Providers made identities more prominent than the patients desired in three ways.

First, providers with different identities than their patients eroded trust by unsuccessfully trying to relate to their patients. In an extreme example, a transgender male remarked that their cis male provider trivialized their difficult experience of finding an appropriate bathroom as a trans person.

“I was talking to him about using the bathrooms and like how difficult it was because back then I was…transitioning and couldn’t find the right bathroom. And he described an experience to me where …he was like…’the men’s bathroom in my office was used, so I used the women’s bathroom.’…It was like a total invalidation of my experience by bringing in his own experience that had like nothing to do with it. Because he’s not trans.”

(Asian queer transgender male)

Second, providers inappropriately focused on their patients’ SGM or AAPI identity, when their primary health concern was unrelated.

“I won’t want to focus on the trans part…unless it’s something that’s pertaining to my condition at that time.”

(Half Indian, half Asian-Indian transgender woman)

Third, providers would over-pathologize issues related to their identities, which one participant described as paternalistic and detrimental to their communication.

“On that list [the provider] wrote down included gender identity disorder……And I really didn’t feel like there was anything I could do to challenge that…her tone of voice suggested…’I’m the doctor. I decide what to put on my paperwork.’”

(Half Chinese, half white bisexual/pansexual transgender man)

Encounter-centered factors impacting SDM

Racial concordance vs. discordance between provider and patient

Many respondents preferred a racially concordant provider because they felt they would not have to explain certain parts of their experiences to them.

“I chose someone with an Asian American background, because I think there’s some commonalities among Asians in terms of lived experience.”

(API gay male)

Other participants preferred a provider of a different race than themselves. For instance, one participant stated:

“I don’t want to go to a doctor who shares the same race as I do, because I know Asians are usually more conservative. So when I have my care provider, I usually prefer white or non-Asians…I guess I probably have this trust issue.”

(Taiwanese gay male)

“[My primary care provider] kind of just assume[s] I’m heterosexual…and he’s a very old school Korean doctor.”

(Asian American gay/queer male)

Other participants expressed concerns about confidentiality, reasoning that if the provider was part of the same racial/ethnic community as the patient, family members may learn about sensitive information such as SGM identity.

“Well if the doctor is Filipino, I would generally avoid [talking about] the whole [SGM] identity, because even though they’re supposed to keep everything confidential, the reality is…being Filipino is a small world, at times. So one person knows and they’re Filipino, somehow it will be traced six degrees of separation. Kind of pretty much happens and gets back to my family.”

(Filipino American gay male)

A few of the participants mentioned how they have had or believe they would have positive experiences with providers who identify as both LGBTQ and as a person of color.

“I was recently able to have one [provider] who is part of the LGBT community and also a person of color. And so talking to them, there’s a lot of things that I didn’t have to explain. That they just immediately got and were able to explain to me why I was going through certain things.

(Biracial/mixed race queer genderqueer individual)

Prominence of AAPI and SGM identities in affecting SDM

Overall, participants reported that their AAPI identity impacted SDM more than did SGM status, but SGM identity was reported more often to negatively affect their mental health. SDM relies on information-sharing12, and AAPI identity is more visible than SGM identity. The ability to choose whether to share their SGM identity with their provider was described by one participant as a “privilege.”

“I’m very privileged in that I can choose to disclose and choose to not disclose for the gender identity and also for the sexual orientation. I don’t have the same power over race.”

(Asian American queer gender-conforming individual)

A feeling of respect for authority notable in AAPI culture may affect how some AAPI SGM approached SDM. One participant detailed a transition in their opinions on SDM that paralleled the evolution of their intersectional identities:

“I feel like because I come from a Filipino family, I have a lot of deference to professionals, and to people in power…And it wasn’t until later on…I started much more actively questioning the treatment. And I think that definitely stemmed from being queer and being exposed to a lot of queer politics and like queer self-determination, and queer ferocity, that I was able to draw upon and really just challenge my providers about the care I was getting.”

(Filipino queer male)

DISCUSSION

Key patient, provider, and encounter-centered factors affect SDM between clinicians and AAPI SGM around mental health issues. SDM was enhanced when providers recognized how patients’ mental health was impacted simultaneously by AAPI and SGM identities and understood how patients’ SGM identity and mental health intersected with family values. Some providers inappropriately dictated the visibility of patients’ multiple identities during the encounter; both under- and over-emphasizing identities degraded trust. Many participants preferred a provider who did not share their race due to concerns about confidentiality and AAPI providers reacting negatively to SGM disclosure. Several reported that their AAPI identity affected SDM more often than did their SGM identity due to its increased visibility compared to SGM identity. Because important variation in perspectives existed, providers should elicit the specific patient-centered factors relevant for each individual patient through clear communication. Making assumptions based on identities may lead to erroneous understanding of patients’ individual experiences and relationships to their identities.

We had previously used existing research, clinical, and personal experience to propose potential themes important for AAPI SGM populations regarding mental health decisions. 20 In a previous paper, we had hypothesized that racial and anti-SGM prejudice as well as isolation from both SGM and heterosexual AAPI communities would influence SDM.20 Our current study supports the importance of these factors. Of note, several respondents reported that a provider sharing a racial or SGM identity with them did not ensure high-quality communication and care.

Figure 1 illustrates the critical experiences, identities, and assumptions that a provider and an AAPI SGM patient bring to a healthcare encounter, building upon a more general model of SDM by Peek et al.12 The left rectangle includes key identity-related experiences of patients. The right rectangle highlights important provider perspectives on the patient and their intersectional identities. In the center are factors directly related to the encounter or exchange of information between the patient and provider.21 Provider assumptions about patient-centered factors may not be correct, as these factors may be invisible to the provider. Incorrect assumptions can degrade trust in the SDM process. Therefore, providers should be aware that family beliefs can influence patient experiences of mental health and SGM identity and should ask patients how their AAPI and SGM identities affect their mental health.

Figure 1.

Conceptual model for shared decision making between providers and Asian American Pacific Islander (AAPI) sexual and gender minority (SGM) patients.

Table 3 depicts our recommendations for the care of AAPI SGM patients, grouped into pre-encounter education, establishing safe space and encouraging disclosure of identities, and questions to ask during the encounter. Prior to the encounter, we recommend that providers educate themselves on the heterogeneity within AAPI and SGM communities, and the specific histories of AAPI and SGM populations. To establish a safe space for disclosure of identities, providers should convey nonjudgment, confidentiality, and openness to the patient’s disclosure on their own terms and timeframe.22 If patients disclose identities, one should react appropriately by neither shirking nor overcompensating, and being mindful of body language. To dispel any ambiguity, it is perhaps best to affirm their identities explicitly, such as with “Thank you for sharing that with me. I am here to support you and can do that best when I know as much about you as possible.” Finally, providers should allow patients to prioritize the issues they want to address during the encounter, inquire about and use their pronouns, and check in regularly about mental health.

Table 3.

Recommendations for Providers Caring for Asian American Pacific Islander Sexual and Gender Minority Patients

| Domain | Recommendation | Patient perspectives |

|---|---|---|

| Pre-encounter education | Recognize heterogeneity within AAPI1 and SGM2 communities | “…And also understand that the LGBTQ3 community is just not under one umbrella…I mean, a queer Asian man is going to have a different experience from a queer black female.” (Queer multiracial Asian man) “…It’s one thing to be identified as Asian American, but there are still differences between like Southeast Asian, South Asian, and everything else as well too. So it’s not a one size fits all.” (Filipino American gay male) |

| Familiarize yourself with AAPI and SGM history and culture, and do not use your patients as learning tools | “Get themselves educated on cultures…at least 70 percent of them have never seen a transgender person in their lives…there are a lot of common threads that unite us all, and that is abuse, whether physical or mental…And I think, you know, understanding this (sic) issues that a transgender person faces before they even walk in the room.” (Half Indian, half Asian-Indian transgender woman) “Well she knows what gay means, and she knows what like bisexual means… [but not queer]. Do I really want to go to a therapist where like I have to spend half the time trying to teach them like what it is that my issues and such.” (Korean/Korean American gay/queer trans male) “They’re using me as a way to learn for themselves…Especially first year residents…How does a guy put a penis in another guy, doesn’t that hurt? These aren’t appropriate questions, who does that? …It’s basically irrelevant questions like either about my racial identity or my sexual identity.” (Mixed Filipino queer cis man) |

|

| Establishing a safe space and encouraging patient disclosure of identities | Help patients feel more comfortable about disclosure | “[The provider could say], ‘I’m open about your sexual identity. It’s an open space, and we’re not going to feel pressured if you don’t want to talk about it.’ (Chinese gay male) “Some people are not comfortable vocalizing [sexual orientation] …especially if they grew up in Asian country rather than in United States…so if they do have a written paper and just a checkmark to check it, that might be easier, especially in their language. If there is a language barrier, I think it would be much easier, so we don’t have to vocalize it.” (Asexual Asian trans male) Ensure confidentiality: “I’ve been to you 15 times but I still need to hear every single time that this is confidential.” (Asian American bisexual female) |

| React appropriately to your patient’s disclosure of SGM identity |

Neutral reaction: “I’d rather have almost like an anti-response than like a [disdainfully] ‘Oh, that…’ response, or [enthusiastically] ‘Oh, that!’ response, you know?” (Asian American gay male) Body language: “When they realized – when I finally disclosed that I was gay, usually their body language, how they reacted towards me, did change.” (San Francisco focus group participant) |

|

| Questions to ask during the encounter | Ask the patient if they would like to set priorities at the beginning of the visit | “I guess a lot of it is timing in terms of this (sic) shared decisions like…what I struggled with is when I have a lot of things going on whether it’s family, my partner, or identities are just like a shitty day that I’m going through, which to focus my energy towards for that day. I can’t tackle it all at once. And in terms of making those decisions with my therapist, you know they are very aware…” (Mixed Filipino queer cis man) (therapist is Asian American and queer) |

| Ask for the patient’s pronouns and use them, and directly address and apologize for misgendering | “Just like slipping [pronouns] up. And they would just blame it [by providing an excuse like] because it’s like a legal thing…[it] really deterred me from even wanting to be within any type of healthcare in general.” (Pacific Islander, Asian queer male) | |

| Check in about mental health | “But if at the point where your physician knows that your sexuality is different – yeah, I think even more so at that point, I would like the physician to really push the envelope and then check in more often about mental health. Because the fact of the matter is, I do feel that being these minority identities, that we do face more challenges more often.” (San Francisco focus group participant) “You know like how they have that graph where it says, ‘How are you feeling today?’ Like your pain level to the like extremely painful? Well, they should have the same thing with, ‘How are you feeling mentally?’…The person who does triage, who takes your vitals, should then note that…The doctor sees that, without you having brought it up. I think that it should be part of the intake process.” (San Francisco focus group participant) |

Asian American Pacific Islander.

Sexual and Gender Minorities.

Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Queer.

Our study is limited because participants volunteered to participate and therefore participants reflect SGM individuals who were comfortable with discussing their identities. Study findings may not generalize to the experiences of the wider AAPI SGM community due to the sampling and limited geography for recruitment; however, generalizability was not the goal of our qualitative study in this understudied population. Exploration of immigration experiences and acculturation may have been limited because most of our participants were U.S. citizens, who may have distinct experiences than those of non-US citizen immigrants. While there are certainly several other factors, e.g. socioeconomic status, that affect SDM in clinical settings, we focus on AAPI and SGM identities as they have particularly powerful, stigmatizing effects,20,23 and we also wanted to avoid covering multiple topics superficially. Although our interview guide included general, open-ended questions, it is possible that the more directed questions around bias towards AAPI and SGM identities led to overrepresentation of these themes. Also, we defined “provider” broadly and did not sub-analyze whether different provider types elicited differences in SDM. We did not distinguish specific SDM decisions from one another.

We have elucidated nuanced barriers and facilitators to effective SDM for AAPI SGM patients, and suggested strategies for providers to communicate better with this population. If providers actively change the many factors within their control, they can help uplift AAPI SGM patients and lessen their mental health distress. Understanding patients’ complex and intersectional stories, which fundamentally influence how they navigate the healthcare encounter, will aid providers in reducing health disparities of AAPI SGM patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

Funding: This project was supported by the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (IU18 HS023050). Ms. Bi and Drs. Laiteerapong and Chin were supported in part by the Chicago Center for Diabetes Translation Research (NIDDK P30 DK092949). Ms. Bi and Dr. Laiteerapong were also supported by the University of Chicago Bucksbaum Institute for Clinical Excellence. Dr. Laiteerapong was supported by American Diabetes Association (1–18-JDF-037). Ms. Polin was supported by the University of Chicago College Research Fellows Program.

Footnotes

Disclosure: The authors declare that they do not have a conflict of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Sutter M, Perrin PB. Discrimination, mental health, and suicidal ideation among LGBTQ people of color. J Couns Psychol. 2016;63(1):98–105. doi: 10.1037/cou0000126 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Chen Y-C, Tryon GS. Dual minority stress and Asian American gay men’s psychological distress. J Community Psychol. 2012;40(5):539–554. doi: 10.1002/jcop.21481 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Meyer IH. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol Bull. 2003;129(5):674–697. doi: 10.1037/0033-2909.129.5.674 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Leong F, Leach M, Yeh C, Chou E. Suicide among Asian Americans: what do we know? What do we need to know? - PubMed - NCBI. https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/17554837. Accessed June 12, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 5.Augsberger A, Yeung A, Dougher M, Hahm HC. Factors influencing the underutilization of mental health services among Asian American women with a history of depression and suicide. BMC Health Serv Res. 2015;15:542. doi: 10.1186/s12913-015-1191-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.McDonald K Social Support and Mental Health in LGBTQ Adolescents: A review of the literature. Issues Ment Health Nurs. 2018;39(1):16–29. doi: 10.1080/01612840.2017.1398283 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Snyder SM, Hartinger-Saunders R, Brezina T, et al. Homeless youth, strain, and justice system involvement: An application of general strain theory. Child Youth Serv Rev. 2016;62:90–96. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.02.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ecker J, Aubry T, Sylvestre J. A Review of the Literature on LGBTQ Adults Who Experience Homelessness. J Homosex. December 2017:1–27. doi: 10.1080/00918369.2017.1413277 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Crenshaw K Demarginalizing the Intersection of Race and Sex: A Black Feminist Critique of Antidiscrimination Doctrine, Feminist Theory and Antiracist Politics. :31.

- 10.Kimberlé Crenshaw on Intersectionality, More than Two Decades Later. Columbia Law School; https://www.law.columbia.edu/pt-br/news/2017/06/kimberle-crenshaw-intersectionality. Accessed June 27, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Chin MH, Lopez FY, Nathan AG, Cook SC. Improving Shared Decision Making with LGBT Racial and Ethnic Minority Patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(6):591–593. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3607-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Peek ME, Lopez FY, Williams HS, et al. Development of a Conceptual Framework for Understanding Shared Decision making Among African-American LGBT Patients and their Clinicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(6):677–687. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3616-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Cooper LA, Roter DL, Johnson RL, Ford DE, Steinwachs DM, Powe NR. Patient-centered communication, ratings of care, and concordance of patient and physician race. Ann Intern Med. 2003;139(11):907–915. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Johnson RL, Roter D, Powe NR, Cooper LA. Patient race/ethnicity and quality of patient-physician communication during medical visits. Am J Public Health. 2004;94(12):2084–2090. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Peek ME, Odoms-Young A, Quinn MT, Gorawara-Bhat R, Wilson SC, Chin MH. “Racism in Healthcare: Its Relationship to Shared Decision-Making and Health Disparities: a response to Bradby.” Soc Sci Med 1982. 2010;71(1):13–17. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2010.03.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ratanawongsa N, Zikmund-Fisher BJ, Couper MP, Van Hoewyk J, Powe NR. Race, ethnicity, and shared decision making for hyperlipidemia and hypertension treatment: the DECISIONS survey. Med Decis Mak Int J Soc Med Decis Mak. 2010;30(5 Suppl):65S–76S. doi: 10.1177/0272989X10378699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stewart M, Brown JB, Donner A, et al. The impact of patient-centered care on outcomes. J Fam Pract. 2000;49(9):796–804. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Greenfield S, Kaplan SH, Ware JE, Yano EM, Frank HJ. Patients’ participation in medical care: effects on blood sugar control and quality of life in diabetes. J Gen Intern Med. 1988;3(5):448–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Stewart MA. Effective physician-patient communication and health outcomes: a review. CMAJ Can Med Assoc J J Assoc Medicale Can. 1995;152(9):1423–1433. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tan JY, Xu LJ, Lopez FY, et al. Shared Decision Making Among Clinicians and Asian American and Pacific Islander Sexual and Gender Minorities: An Intersectional Approach to Address a Critical Care Gap. LGBT Health. 2016;3(5):327–334. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2015.0143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.DeMeester RH, Lopez FY, Moore JE, Cook SC, Chin MH. A Model of Organizational Context and Shared Decision Making: Application to LGBT Racial and Ethnic Minority Patients. J Gen Intern Med. 2016;31(6):651–662. doi: 10.1007/s11606-016-3608-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cook SC, Gunter KE, Lopez FY. Establishing Effective Health Care Partnerships with Sexual and Gender Minority Patients: Recommendations for Obstetrician Gynecologists. Semin Reprod Med. 2017;35(5):397–407. doi: 10.1055/s-0037-1604464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Tan JY, Baig AA, Chin MH. High Stakes for the Health of Sexual and Gender Minority Patients of Color. J Gen Intern Med. 2017;32(12):1390–1395. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4138-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.