Abstract

Rationale:

Compromised protein quality control can result in proteotoxic intracellular protein aggregates in the heart, leading to cardiac disease and heart failure. Defining the participants and understanding the underlying mechanisms of cardiac protein aggregation is critical for seeking therapeutic targets. We identified ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 variant 1 (Ube2v1) in a genome-wide screen designed to identify novel effectors of the aggregation process. However, its role in the cardiomyocyte is undefined.

Objective:

To assess whether Ube2v1 regulates the protein aggregation caused by cardiomyocyte expression of a mutant αB crystallin (CryABR120G) and identify how Ube2v1 exerts its effect.

Methods and Results:

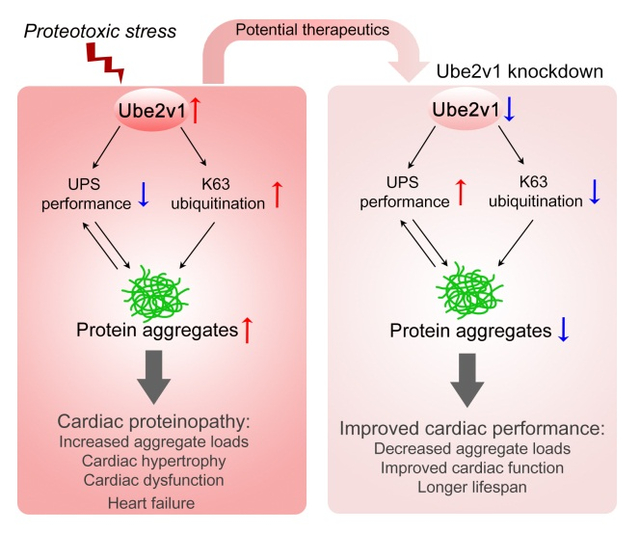

Neonatal rat ventricular cardiomyocytes (NRVMs) were infected with adenoviruses expressing either wild-type CryAB (CryABWT) or CryABR120G. Subsequently, loss- and gain-of-function experiments were performed. Ube2v1 knockdown decreased aggregate accumulation caused by CryABR120G expression. Overexpressing Ube2v1 promoted aggregate formation in CryABWT and CryABR120G-expressing NRVMs. Ubiquitin proteasome system (UPS) performance was analyzed using a UPS reporter protein. Ube2v1 knockdown improved UPS performance and promoted the degradation of insoluble ubiquitinated proteins in CryABR120G cardiomyocytes but did not alter autophagic flux. Lys (K) 63-linked ubiquitination modulated by Ube2v1 expression enhanced protein aggregation and contributed to Ube2v1’s function in regulating protein aggregate formation. Knocking out Ube2v1 exclusively in cardiomyocytes by using adeno-associated virus 9 (AAV9) to deliver multiplexed single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) against Ube2v1 in cardiac-specific Cas9 mice alleviated CryABR120G-induced protein aggregation, improved cardiac function and prolonged lifespan in vivo.

Conclusions:

Ube2v1 plays an important role in protein aggregate formation, partially by enhancing K63 ubiquitination during a proteotoxic stimulus. Inhibition of Ube2v1 decreases CryABR120G-induced aggregate formation through enhanced ubiquitin proteasome system performance rather than autophagy and may provide a novel therapeutic target to treat cardiac proteinopathies.

Keywords: Ube2v1, ubiquitin, proteasome, desmin-related cardiomyopathy, basic science, cell singaling, signal transduction

Subject Terms: Animal Models of Human Disease, Basic Science Research, Cell Signaling/Signal Transduction, Myocardial Biology

Graphical Abstract:

INTRODUCTION

Protein homeostasis is critical for the maintenance of cellular function and organismal viability.1 It involves multiple processes that coordinate protein synthesis, folding, disaggregation and degradation.2 The loss or imbalance of proteostasis causes the accumulation of misfolded and aggregated proteins with consequent proteotoxicity. Proteinopathies are now recognized as part of the pathology driving progression of an increasing number of disease states, including cardiovascular disease, type II diabetes, cancer, peripheral amyloidosis and neurodegenerative disease.3 However, no clinical therapy targeting proteinopathies is currently available for treating cardiac diseases. Toxic, pre-amyloid oligomers and protein aggregates have been identified in cardiomyocytes isolated from patients with hypertrophic, idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy and heart failure.4, 5 Subsequent to the perinatal period, cardiomyocytes become largely post-mitotic and possess limited replicative capacity. As such, over time they can accumulate misfolded protein aggregates, which can contribute to the progression of cardiac disease and heart failure.6–8 Thus, we hypothesize that therapeutic approaches targeted to reduce misfolded proteins or inhibit protein aggregation will slow the progression of cardiac proteinopathy and improve cardiac function.9–11

Multiple protein quality control (PQC) mechanisms modulate protein synthesis and stabilization, tightly orchestrating proteostasis to ensure cellular protein integrity.12, 13 PQC insufficiency allows misfolded proteins to undergo aberrant aggregation and the accumulation of misfolded and aggregated proteins further impairs PQC in a feedforward mechanism.14 The ubiquitin-proteasome system (UPS) and autophagy-lysosome pathway are two major proteolytic cascades to eliminate misfolded proteins, large aggregates and damaged organelles.7 Suppressing PQC by deleting a chaperone gene or blocking proteolysis results in cardiac dysfunction and heart failure.15, 16 Conversely, under proteotoxic stress, improving PQC by upregulating molecular chaperone activity or enhancing the UPS or autophagy can help remove misfolded or aggregated proteins and improve cardiac function and the probability of survival.17–22 Hence, controlling protein quality by improving ubiquitin proteasome functioning or autophagic flux is implicated as a potential strategy to treat cardiac proteinopathies.

The UPS is responsible for the degradation of ubiquitinated, misfolded and short-lived proteins. It requires three distinct enzymes, E1, E2 and E3 to covalently add ubiquitin to lysines of targeted proteins and the subsequent elongation of the growing poly-ubiquitin chain, which then serves as a signal for proteasome-mediated degradation.23 Ubiquitin conjugating enzyme E2 variant proteins are a distinct subfamily of the E2 protein family. They have sequence similarity to other E2s but lack the conserved cysteine residue that is critical for the catalytic activity of E2s.24 Ubiquitin conjugating enzyme E2 variant 1 (Ube2v1), also known as Uev1a, is a mammalian homolog of yeast MMS2 and a co-factor of ubiquitin conjugating enzyme E2 N (Ube2n).25 Several lines of evidence support a close correlation between Ube2v1 and carcinogenesis, suggesting that Ube2v1 can act as a potential proto-oncogene. For example, the Ube2v1-Ube2n enzyme complex promotes breast cancer metastasis.26 Inhibition of the Ube2v1-Ube2n complex can reduce proliferation and survival of large B-cell lymphoma cells in vitro,27 and also induces neuroblastoma cell death in vivo.28 However, whether Ube2v1 modulates UPS function in the heart is completely unknown.

Using a genome-wide short hairpin RNA screen, we sought novel genes that could prevent or clear proteotoxic aggregates in a proteotoxic model of desmin-related cardiomyopathy. Genetic studies linked this disease to mutations in a number of different genes including those encoding desmin, αB-crystallin (CryAB) and myotilin.29 The most common form of desmin-related cardiomyopathy results from a missense mutation, R120G, in CryAB (CryABR120G),30 and we have extensively characterized a mouse model in which CryABR120G is expressed specifically in cardiomyocytes.31 The disease is characterized by the presence of desmin- and other proteins forming electron-dense granulofilamentous aggregates in cardiomyocytes.32 The high throughput screen showed that Ube2v1 was one of the candidates that might regulate cardiomyocyte protein aggregation.33 Given that Ube2v1 is expressed at a relatively low level in the heart, this was unexpected and its cardiac function is largely unresolved. Here, we demonstrate that Ube2v1 modulates proteotoxic load in CryABR120G-based desmin-related cardiomyopathy, partially through K63 ubiquitination. We show that inhibition of Ube2v1 blocked CryABR120G-induced protein aggregate formation through improved UPS performance. AAV9-delivered single guide RNAs (sgRNAs) targeting to Ube2v1 effectively decreased cardiac aggregate loads and improved cardiac function in CryABR120G transgenic (Tg) mice, providing proof of principle for potential cardiac proteinopathy therapies.

METHODS

The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Full details of methods are described in the Online Supplement. Please see the Major Resources Table in the Supplemental Materials.

Animals.

Non-transgenic (Tg) and Tg mice with cardiomyocyte-restricted overexpression of CryABR120G have been described.31 Cardiac-specific Cas9 Tg mice with a TdTomato tag (Myh6-Cas9-TdTomato), a gift from Eric N. Olson, has been previously described.34 Both male and female mice were used interchangeably and grouped for treatment with no blinding but randomized in this study. No animals were excluded from analysis. All quantifications were performed by personnel blinded to mouse genotype and treatment. Animals were handled in accordance with the principles and procedures of the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. The Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital approved all experimental procedures.

Neonatal rat ventricular myocyte isolation.

Primary neonatal ventricular myocytes (NRVMs) were isolated from the ventricles of 1–2-day-old Sprague-Dawley rats as described previously.35

AAV production and delivery.

The DNA fragment containing 4 different sgRNAs against Ube2v1 driven by either the human or mouse U6 promoter (Online Figure VIA and VIB) was designed by the Transgenic Core at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center and synthesized by GenScript. The fragment was inserted into an AAV vector (Addgene plasmid #85451) and the recombinant genome was subsequently packaged into AAV capsid serotype-9. Infectious recombinant AAV vector particles were generated by Vigene Biosciences, indicated as AAV9-sgRNAv1.

Postnatal day 10 mice were administered 1×1012 viral genomes of AAV diluted in 30 μl PBS via i.p. injection. AAV9-GFP, which expressed GFP driven by the cytomegalovirus promoter, was used as a control.

Measurement of uniquitin proteasome system performance and autophagic flux.

NRVMs were infected with adenovirus containing the degron GFPu, an inverse reporter of the ubiquitin proteasome system.35 UPS performance was measured by quantitating fluorescence and by Western blot analysis of GFPu. To measure autophagic flux, NRVMs were infected with AdGFP-CryABR120G and then transfected with either scrambled or Ube2v1 siRNA. Cells were treated with Bafilomycin A1 (Sigma; B1793) at 50 nmol/L for 3 hours prior to harvest. Autophagic flux was determined by quantitating microtubule-associated light chain-II (LC3-II) using Western blots.

Cell fractionation.

NRVMs were lysed in CelLytic M buffer (Sigma) containing a protease inhibitor mixture (Roche). The cells were centrifuged and supernatants collected, constituting the soluble fraction. The pellets were dissolved in DNAse I (Roche), homogenized with a plastic pellet pestle, and gently sonicated, generating the insoluble fraction.

Statistical analysis.

Representative images were selected reflecting the average level of n=3–10 for each experiment. Each data point represents an independent biological sample. All parameters are presented as mean±SEM. Statistical analyses were performed using GraphPad Prism 8. Normal distribution was examined using the Shapiro-Wilk test. Data were analyzed using the unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test between 2 groups. For multiple comparisons, one-way or two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post hoc testing was used, and adjusted P-values for each comparison were reported. Kaplan-Meier survival curves using the Log-rank test were generated. Experiment-wide multiple test correction was not applied. A value of P<0.05 was considered statistically significant.

RESULTS

Ube2v1 expression in CryABR120G-expressing cardiomyocytes is enhanced and knockdown decreases aggregate formation.

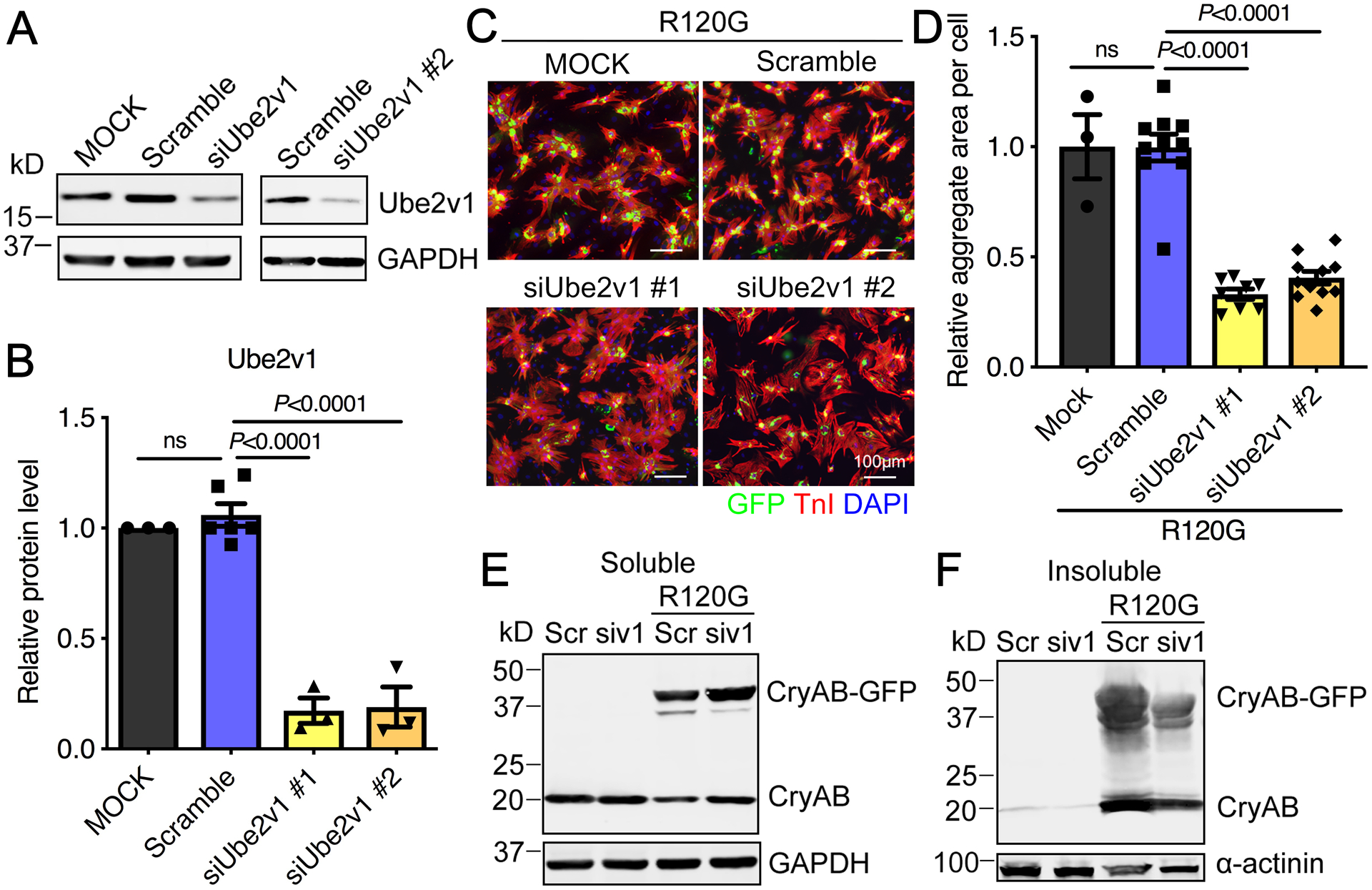

As reported previously, AdGFP-CryABWT infected cardiomyocytes showed diffuse GFP distribution, but AdGFP-CryABR120G infected cells exhibited large, GFP-positive aggregates that accumulate in the perinuclear region between 3–5 days (Online Figure I). Our previous screen, seeking novel gene products that affected aggregate formation in cardiomyocytes,33 showed that knockdown of the E2 ubiquitin conjugating enzyme Ube2v1 effectively decreased cardiomyocyte protein aggregation. We validated these initial data by preparing two different Ube2v1 siRNAs, siUbe2v1 #1 and #2, and transfecting them separately into NRVMs to test the knockdown efficiency. Both significantly reduced Ube2v1 protein levels (Figure 1A and 1B). To determine the effects of Ube2v1 knockdown on protein aggregate accumulation, we infected NRVMs with adenovirus encoding GFP-CryABR120G. siRNA was transfected 1-day post-infection and cells harvested 5 days later for GFP immunostaining in order to detect the protein aggregates. The immunostaining (Figure 1C) and quantitation data (Figure 1D) showed that knockdown of Ube2v1 using either siUbe2v1 #1 or #2 dramatically lowered aggregate loads caused by CryABR120G expression. Western blot analysis (Figure 1E), comparing lane 3 with lane 4, showed that soluble CryAB levels, indicating non-aggregation, were increased by Ube2v1 knockdown in the CryABR120G expressing cells. The amount of CryAB in the insoluble fraction, indicating aggregation, was dramatically reduced by Ube2v1 knockdown as well (Figure 1F). The data show that decreased Ube2v1 levels lead to decreased CryABR120G-induced protein aggregation.

Figure 1. Ube2v1 knockdown inhibits CryABR120G-induced protein aggregation.

A, Western blot analysis showed effective siRNA knockdown of Ube2v1 in NRVMs. GAPDH was used as a loading control. B, Data shown in panel A were quantitated. C, NRVMs were infected with AdGFP-CryABR120G and then transfected with either a scrambled siRNA (Scramble) or siRNAs to Ube2v1 as indicated. At 5 days post-infection, NRVMs were fixed and immunostained with troponin I (TnI; red) to identify the cardiomyocytes and DAPI (nuclear staining; blue). Scale bar=100 μm. D, Aggregates in NRVMs were quantitated using NIS-elements software. At least 100 cells per group were quantitated. E and F, siUbe2v1 #1 was transfected into NRVMs and Western blots used to quantitate CryAB protein in the soluble and insoluble fractions as indicated. GAPDH and α-actinin were used as loading controls as indicated. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparisons for B and D. Data are shown as mean±SEM. ns; non-significant (P>0.05). Scr; scrambled siRNA control, siv1; siUbe2v1. R120G; AdGFP-CryABR120G. MOCK; mock transfected cells.

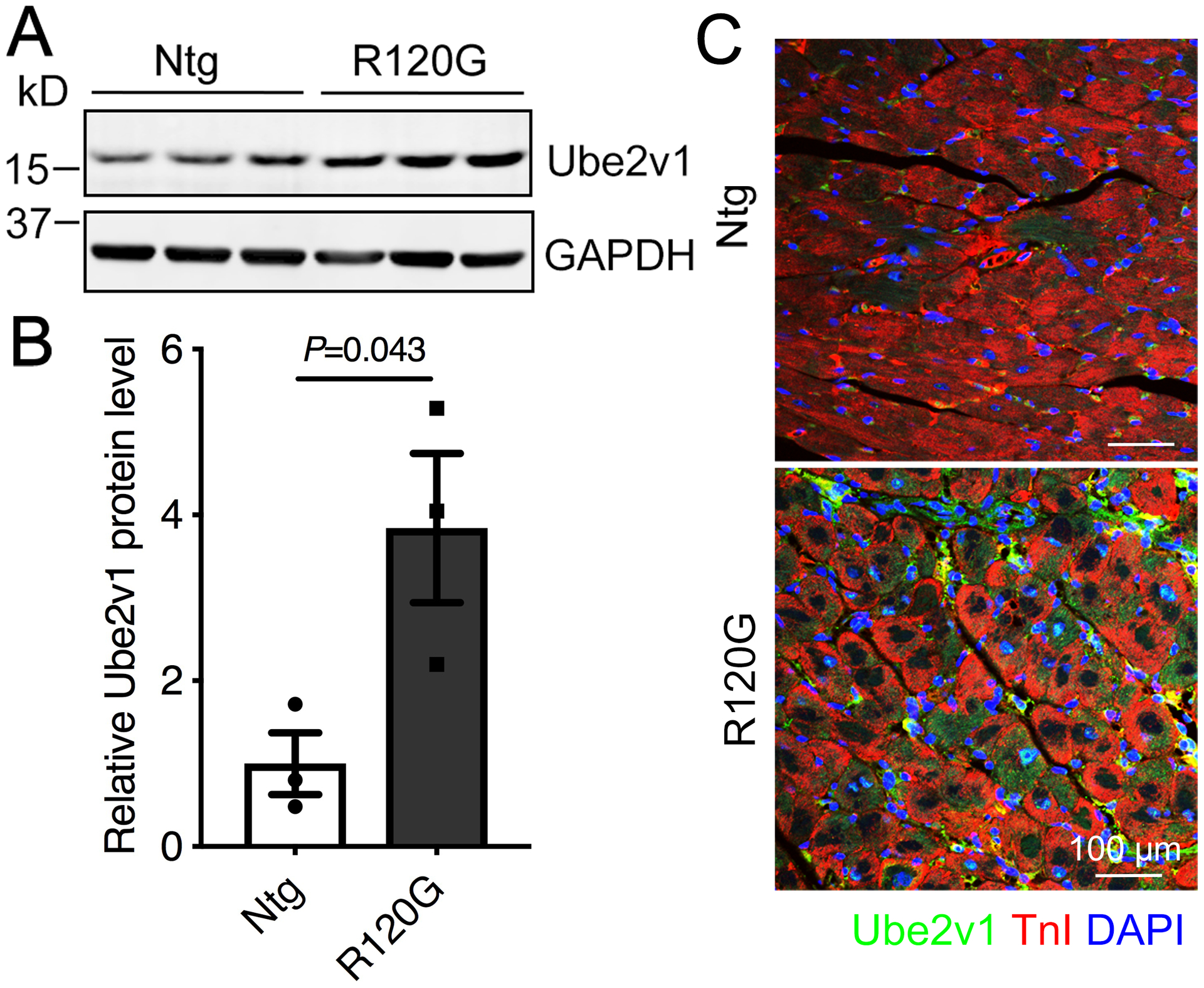

To evaluate the potential role of Ube2v1 in cardiac proteinopathy, we initially investigated Ube2v1 expression in the CryABR120G Tg mice. Western blots showed that Ube2v1 protein expression was significantly increased in 5-month old CryABR120G hearts, which are functionally impaired compared with non-Tg hearts (Figure 2A and 2B). Elevated Ube2v1 expression in 5-month old CryABR120G hearts was confirmed by immunostaining (Figure 2C). These data, while correlative, are consistent with the hypothesis that Ube2v1 expression may enhance proteotoxic aggregate formation and function in the progression of CryABR120G-induced cardiomyopathy.

Figure 2. The expression profile of Ube2v1 in CryABR120G hearts.

A, Western blot showing Ube2v1 expression levels in 5-month old CryABR120G hearts (n=3, two males and one female per group). GAPDH was used as a loading control. B, Density analyses of the complete Western blot data. C, A 5-month old heart section was immunostained with Ube2v1 (green) and the cardiomyocyte marker troponin I (TnI; red). Nuclei were counterstained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar=100 μm. Unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test for B. Data are shown as mean±SEM. Ntg; non-transgenic, R120G; CryABR120G transgenic.

Ube2v1 overexpression increases protein aggregate load and modulates ubiquitinated protein levels.

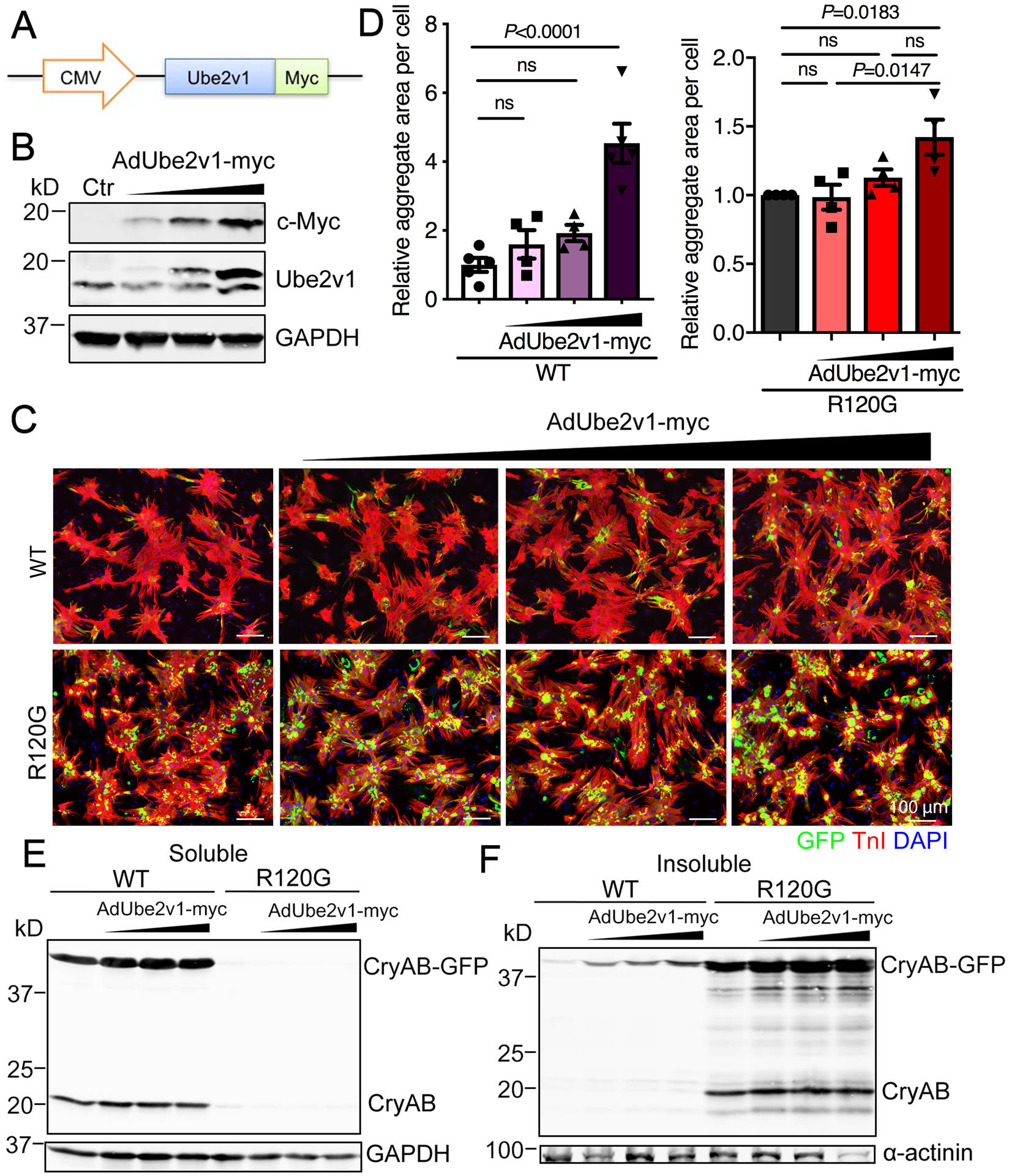

We then determined directly the consequences of increased Ube2v1 expression on protein aggregation. We generated Ube2v1 adenovirus containing a c-Myc-tag linked to a cytomegalovirus promoter to drive high levels of expression (Figure 3A). Western blot analysis showed dose-dependent protein levels (Figure 3B). The upper band in Panel B is the Ube2v1-myc fusion protein and it increases with increasing multiplicities of infection of the virus, while the lower band, representing endogenous Ube2v1, remains constant at all virus dosages. NRVMs were coinfected with Ube2v1-myc adenovirus and either GFP-CryABWT or GFP-CryABR120G. Five days later, we collected the cells and quantitated the CryAB-containing aggregates. Ube2v1 overexpression enhanced the aggregate content both in AdGFP-CryABWT- and AdGFP-CryABR120G-infected cells in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 3C and 3D), indicating that elevated Ube2v1 expression enhances CryAB-driven protein aggregation. To confirm this, we analyzed the soluble and insoluble protein fractions from Ube2v1 and CryAB infected cells by Western blotting with CryAB antibody. CryAB protein partitioned mainly in the soluble fraction derived from the CryABWT-infected cells. In contrast, CryAB protein from the CryABR120G-infected cells was essentially all in the insoluble fraction (Figure 3E and 3F), although Ube2v1 also led to detectable aggregates in the CryABWT infected cells (Figure 3F), consistent with a small number of visible aggregates (Figure 3C). Thus, enhanced Ube2v1 expression leads to increased aggegate formation in both normal and proteotoxic cardiomyocyte cultures.

Figure 3. Ube2v1 overexpression promotes protein aggregate formation.

A, Schematic representation of the recombinant adenovirus encoding Ube2v1-c-myc fusion protein. B, NRVMs were infected with AdUbe2v1-myc at different multiplicities of infection. The Western blot shows the protein expression levels of the c-Myc tag and Ube2v1. GAPDH was used as a loading control. C, NRVMs were coinfected with either AdGFP-CryABWT or AdGFP-CryABR120G and AdUbe2v1-myc. At 5 days post-infection, NRVMs were fixed and immunostained with troponin I (TnI; red) and DAPI (nuclear staining; blue). Scale bar=100 μm. D, Aggregates in NRVMs were quantitated using NIS-elements software. At least 100 cells per group were quantitated. E, Soluble CryAB expression was detected by Western blot. GAPDH was used as a loading control. F, Insoluble CryAB expression was detected by western blot after protein solubilization. α-actinin was used as a loading control. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparisons for D. Data are shown as mean±SEM. ns; non-significant (P>0.05). Ctr; non-infected cells, CMV; cytomegalovirus, WT; AdGFP-CryABWT, R120G; AdGFP-CryABR120G.

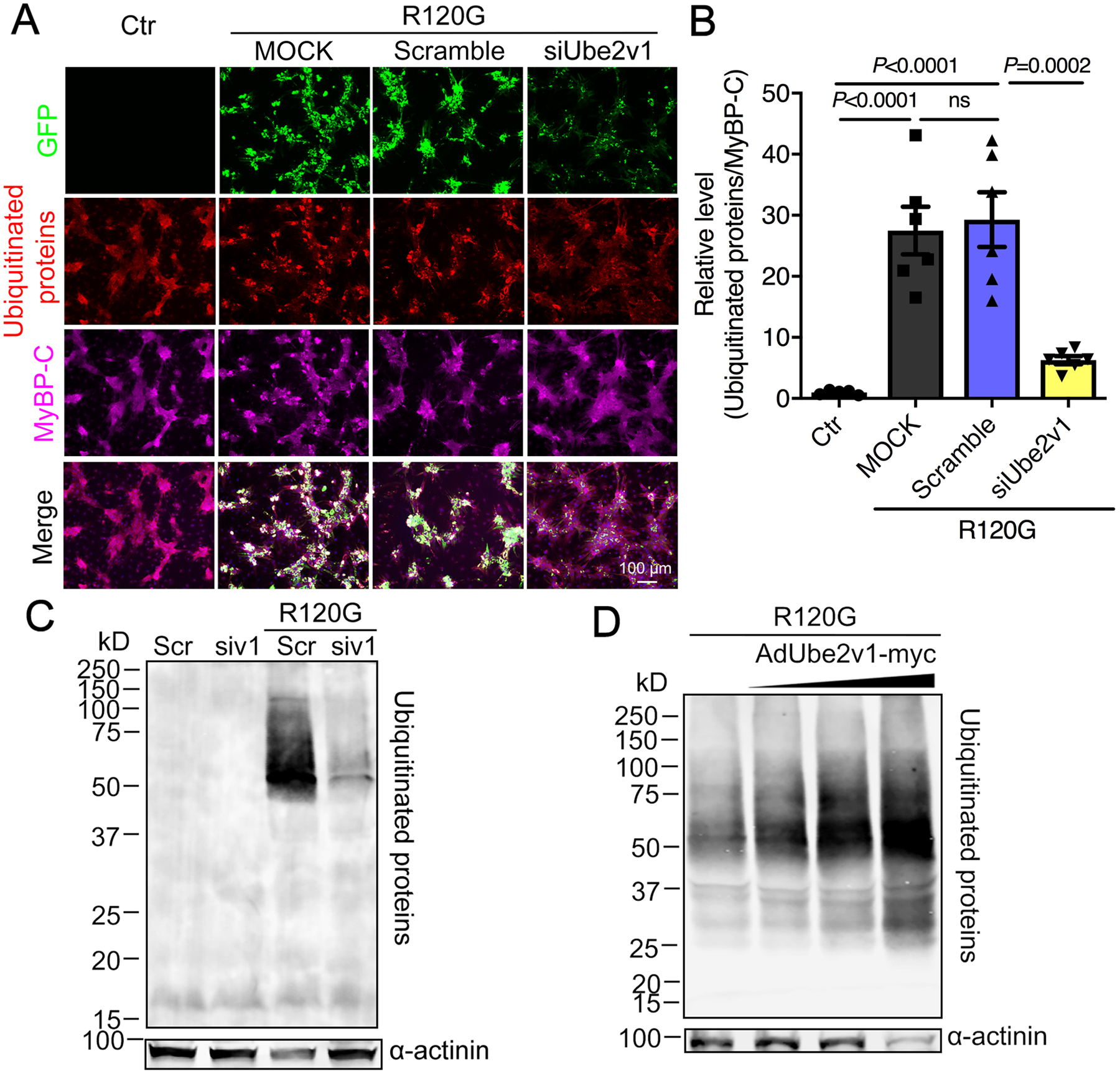

As CryABR120G is misfolded and large aggregates form, they can interfere with the proteasome, leading to proteasomal functional insufficiency and accumulation of ubiquitinated proteins in cardiomyocytes.36 As increased Ube2v1 levels increased CryABR120G-mediated aggregation, we hypothesized that it would also lead to increased levels of ubiquitinated protein as these would be unable to undergo normal processing through the proteasome. Conversely, Ube2v1 knockdown should decrease ubiquitinated protein load as large aggegate formation would be decreased, while misfolded, ubiquinated proteins would be rapidly degraded by the proteasome. CryABR120G-expressing cardiomyocytes were transfected with siUbe2v1 and the ubiquitinated proteins compared to the control, mock transfected, and si-scrambled RNA treated cells using immunofluorescent microscopy. siUbe2v1 knockdown effectively decreased overall ubiquitinated protein levels (Figure 4A and 4B). Similarly, ubiquitin conjugated protein levels in the insoluble fraction of CryABR120G infected cells were also significantly decreased by Ube2v1 knockdown (Figure 4C). Conversely, coinfection of NRVMs with CryABR120G- and Ube2v1-containing adenovirus resulted in a dose-dependent increase in the level of insoluble ubiquitinated proteins (Figure 4D). Thus, Ube2v1 expression affects overall protein aggregation while also leading to increased levels of ubiquitination in the cardiomyocytes, presumably because of the proteasome’s inability to process the aggregated ubiquitin-conjugated proteins.36

Figure 4. Ube2v1 impacts cardiomyocyte protein ubiquitination.

A, NRVMs were transfected as indicated and subjected to immunohistochemical analyses using anti-ubiquitin (red) and anti-myosin binding protein C (MyBP-C) to detect the cardiomyocytes (purple). Scale bar=100 μm. B, Quantification of ubiquitinated protein levels in NRVMs using NIS-elements software. At least 100 cells per group were analyzed. C, Western blot showing insoluble ubiquitinated proteins. α-actinin was used as a loading control. Scr; scrambled siRNA control, siv1; siUbe2v1. D, Western blot showing insoluble ubiquitinated protein levels in NRVMs coinfected with AdUbe2v1-myc and AdGFP-CryABR120G. α-actinin was used as a loading control. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparisons for B. Data are shown as mean±SEM. ns; non-significant (P>0.05). Ctr; non-transfected cells, MOCK; mock transfected NRVMs, R120G; AdGFP-CryABR120G infected NRVMs.

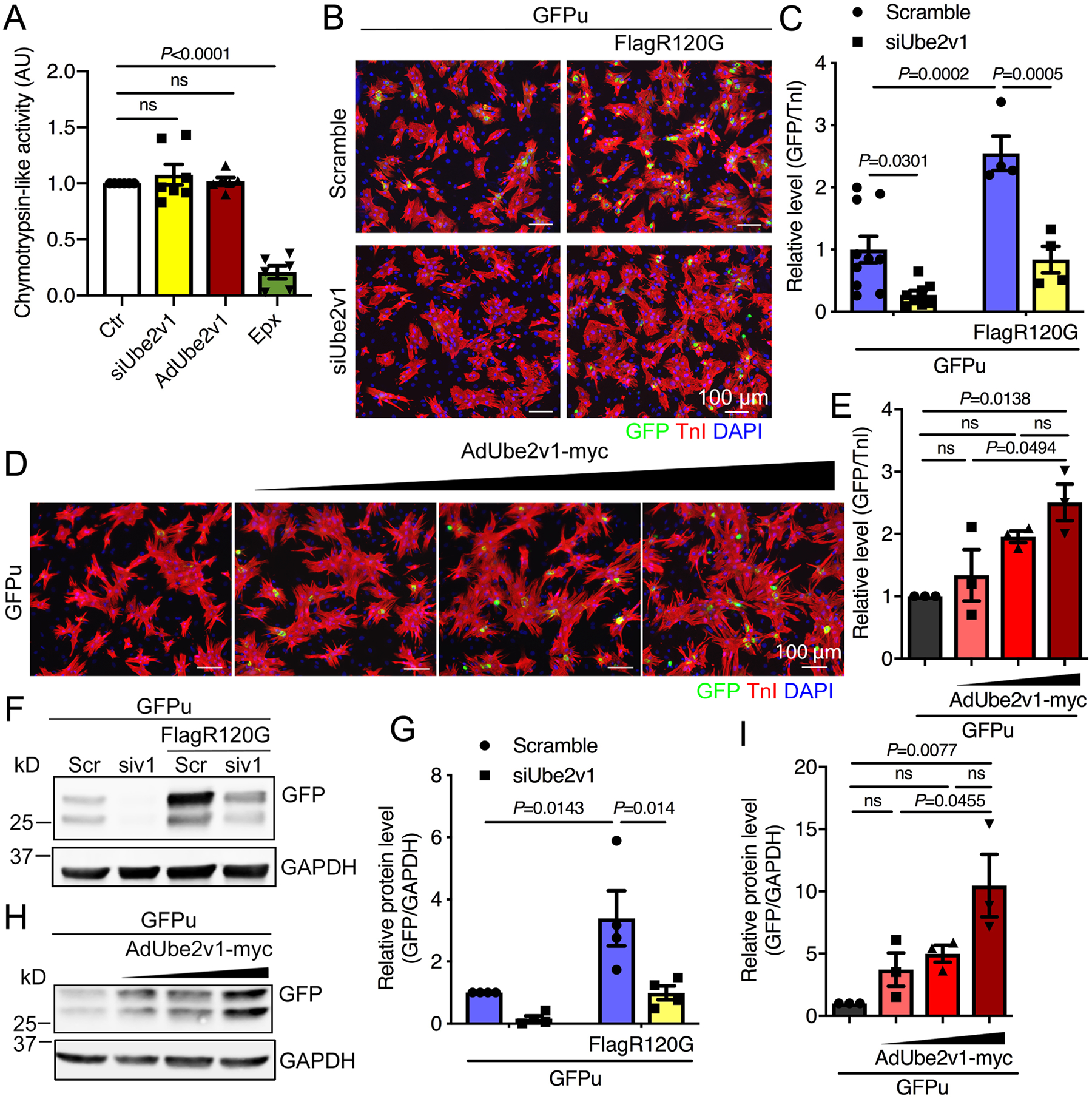

We directly tested the effect of Ube2v1 loss- and gain-of-function on proteasome-mediated proteolytic function in NRVMs. 20S proteasomal activity was assayed by determining chymotrypsin-like activity. Proteasomal activity was unaltered by Ube2v1 knockdown or overexpression (Figure 5A), while the selective proteasomal inhibitor, epoxomicin, effectively inhibited activity in the assay. We conclude that Ube2v1 does not act directly on core proteasomal function. An inverse reporter of the UPS consisting of a short degron, CL1 fused to the COOH-terminus of green fluorescent protein (GFPu), was then used to measure UPS performance by detecting GFPu levels.37 As this is an inverse reporter system, an increase in GFPu protein indicates decreased UPS performance.18 We coinfected NRVMs with adenoviruses containing the GFPu degron and a Flag tagged-CryABR120G together,38 or infected with only AdGFPu, and measured GFP levels directly using both immunofluorescent microscopy and Western blotting with anti-GFP. Ube2v1 knockdown markedly decreased the levels of GFP in both noninfected and AdFlag-CryABR120G-infected cardiomyocytes, indicating increased proteasomal flux by Ube2v1 inhibition (Figure 5B and 5C). Conversely, Ube2v1 overexpression increased the levels of GFP in a dose-dependent manner (Figure 5D and 5E). Western blots confirmed the immunohistochemical data for both the siRNA knockdown (Figure 5F and 5G) and the Ube2v1 overexpression experiments (Figure 5H and 5I).

Figure 5. Proteasomal activity is negatively affected by Ube2v1 expression.

A, Chymotrypsin-like proteasomal activity in NRVMs infected with Ad-Ube2v1. Epx; epoxomicin, AU; arbitrary unit. B, NRVMs were coinfected with an adenovirus vector expressing an inverse reporter of the UPS; AdGFPu, and adenovirus containing a Flag-tagged CryABR120G (AdFlag-R120G). NRVMs were subsequently transfected with scrambled (Scr) or Ube2v1 (siv1) siRNA and cultured for 4 days. Cells were fixed and immunostained with troponin (TnI) to identify the cardiomyocytes and the nuclei stained with DAPI. Scale bar=100 μm. C, Quantitation of GFP levels in NRVMs using NIS-elements software. At least 100 cells per group were quantitated. D, NRVMs were coinfected with AdGFPu and AdUbe2v1-myc. Five days later, cells were fixed and immunostained with TnI and DAPI. Scale bar=100 μm. E, Quantitation of GFP levels in NRVMs using NIS-elements software. At least 100 cells per group were quantitated. F and H, Western blots of GFP expression levels. GAPDH was used as a loading control. G and I, The Western blots were quantitated. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparisons for A, E and I. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparisons for C and G. Data are shown as mean±SEM. ns; non-significant (P>0.05). Ctr; untreated cells.

We also measured UPS performance using the selective proteasome inhibitor epoxomicin.39 NRVMs were infected with AdGFPu and then transfected with either scrambled or Ube2v1 siRNA. Subsequently, the transfected cells were treated with epoxomicin for 15 hours before fixation and immunostained to determine GFPu levels relative to TnI as a measure of proteasomal flux in cardiomyocytes. Inhibition of the UPS by epoxomicin abolished the effect that Ube2v1 knockdown had on GFPu degradation (Online Figure IIA and IIB). Taken together, the data show that cardiomyocyte UPS proteolytic performance independent of the proteasome’s intrinsic activity can be modified by manipulating Ube2v1 expression.

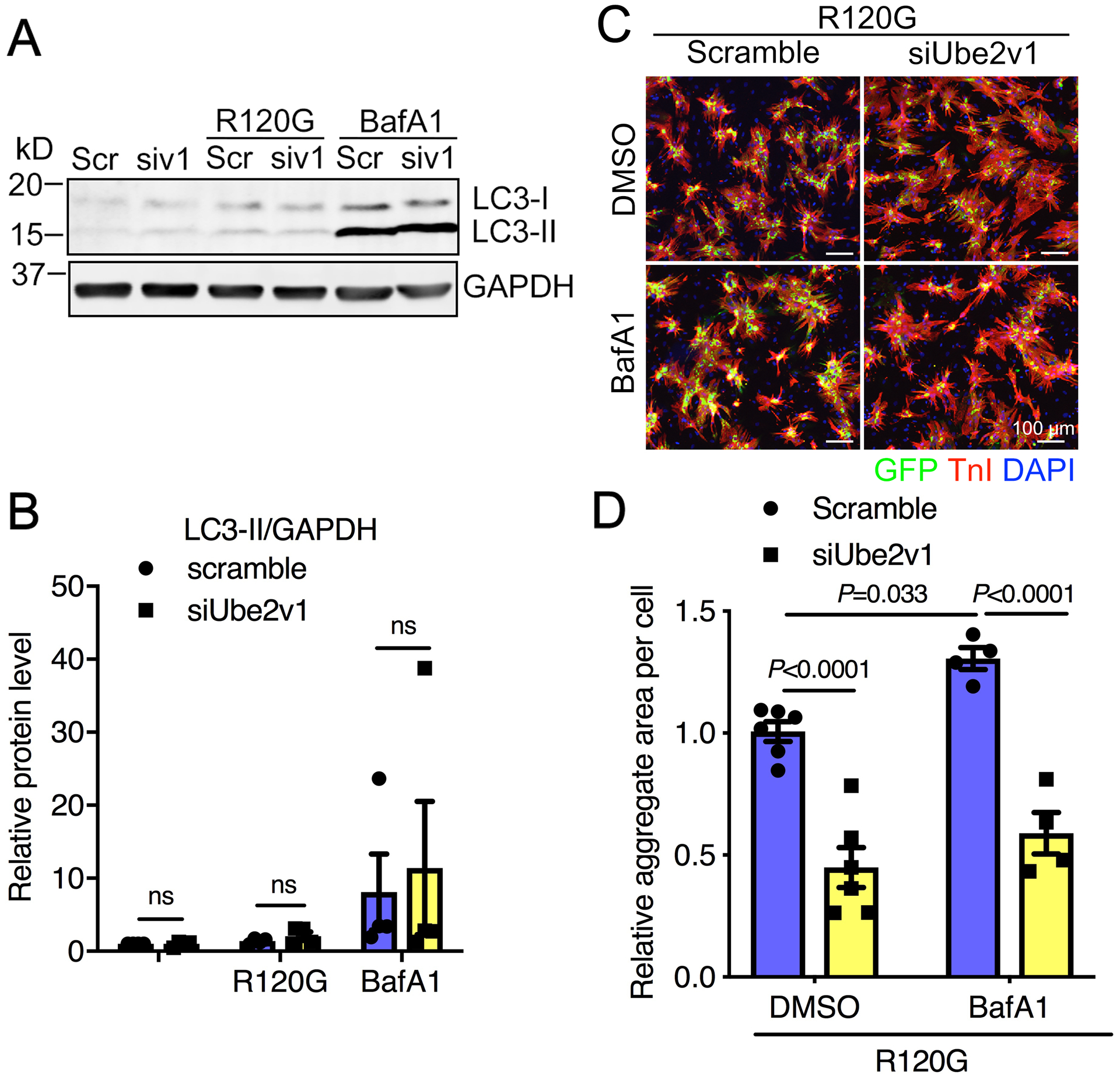

Autophagy is not affected by Ube2v1 knockdown.

Autophagy is the other major proteolytic pathway that is compromised in the CryABR120G model.17 Previously, we demonstrated that upregulating autophagy effectively reduced protein aggregate loads, increased cell viability, and enhanced the probability of survival in CryABR120G Tg mice.20, 40 Therefore we wished to determine if Ube2v1 expression affected autophagic flux. Western blot analysis showed that the levels of the autophagic marker LC3-II were unchanged by Ube2v1 knockdown in normal NRVMs or when the cells expressed CryABR120G (Figure 6A and 6B), suggesting that autophagic flux was unaffected. We then treated the cells with the autophagosome-lysosome fusion inhibitor Bafilomycin A1 to determine if autophagic flux was affected,9 but could detect no differences in the scrambled versus siUbe2v1 transfected cells (Figure 6A and 6B). To confirm these results, we treated CryABR120G-expressing NRVMs with Bafilomycin A1. As expected, inhibiting autophagy significantly promoted the accumulation of protein aggregate loads (Figure 6C, Scramble panels). However, even when autophagy was inhibited, Ube2v1 knockdown blocked CryABR120G-induced protein aggregation (Figure 6C and 6D). We conclude that inhibition of Ube2v1 ameliorates CryABR120G-induced protein aggregate formation through enhanced UPS performance and that autophagy is not required for this to occur.

Figure 6. NRVM autophagic flux is not affected by Ube2v1 knockdown.

Cells were infected with AdGFP-CryABR120G and then transfected with scrambled (Scr) or Ube2v1 (siv1) siRNA. Subsequently, cells were treated with the lysosomal inhibitor Bafilomycin A1 (BafA1) at 50 nmol/L for 3 hours. A, Western blot showing microtubule-associated light chain-I and -II (LC3–1, LC3-II) levels. GAPDH was used as a loading control. B, The Western blot was quantitated. C, Cells were fixed and immunostained with troponin I (TnI) and DAPI. Scale bar=100 μm. D, Aggregates were quantitated using NIS-elements software. At least 100 cells per group were quantitated. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparisons for B and D. Data are shown as mean±SEM. ns; non-significant (P>0.05). R120G; AdGFP-CryABR120G infected NRVMs.

K63 ubiquitination is modulated by Ube2v1 andpPromotes CryABR120G protein aggregation.

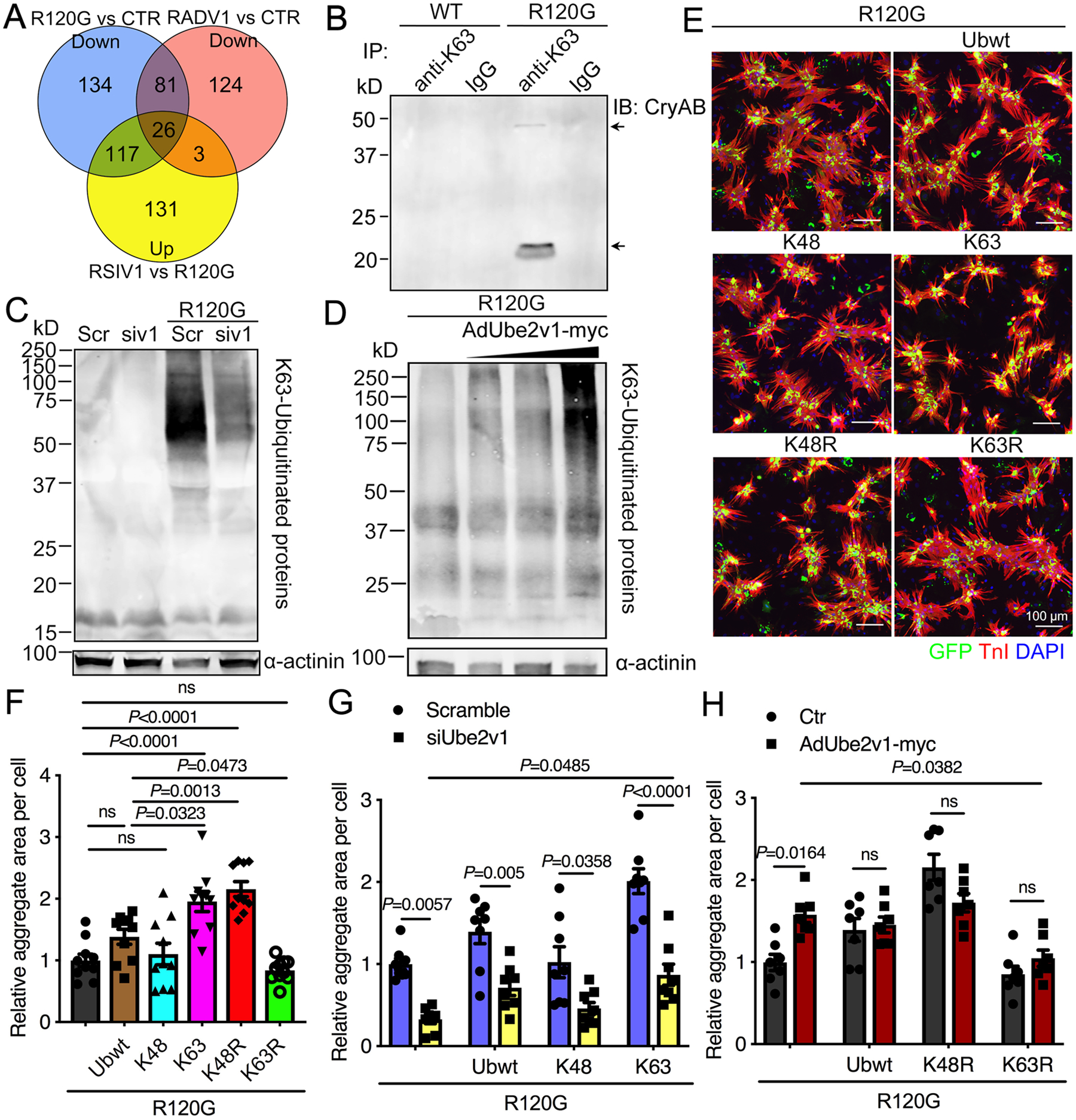

To explore potential underlying molecular mechanisms at the single gene expression level and potentially identify genes associated with the protein aggregation processes regulated by Ube2v1, we performed transcriptome analyses in untreated control (CTR), AdGFP-CryABR120G-infected (R120G), AdGFP-CryABR120G + siUbe2v1-treated (RSIV1), and AdGFP-CryABR120G + AdUbe2v1-myc-treated (RADV1) cells. Expression analyses and heat map visualization of transcripts associated with proteasomal function showed enhanced expression of proteasome-associated genes in AdCryABR120G-infected NRVMs (Online Figure IIIA and IIIB), consistent with a compensatory response to decreased proteasomal efficiency under proteotoxic stress. Ube2v1 knockdown in AdCryABR120G-infected NRVMs resulted in restoration of a gene expression profile of the proteasome gene family similar to untreated cardiomyocytes (CTR) (Online Figure IIIA), while overexpression of Ube2v1 in CryABR120G-expressing NRVMs resulted in a gene expression profile that mimicked the patterns observed for AdCryABR120G infection (Online Figure IIIB). Generally, the transcriptome of CryABR120G-expressing NRVMs showed significant differences compared with normal NRVMs. To define the effects on expression of Ube2v1 knockdown in CryABR120G-expressing cells, we compared the differential gene expression patterns between R120G versus CTR and RSIV1 versus R120G. The heat map showed that Ube2v1 knockdown resulted in a more normal expression pattern (Online Figure IVA). Of the 181 differentially expressed genes in these two comparisons (Online Table I), 37 genes that were upregulated in CryABR120G-expressing cells were downregulated by Ube2v1 knockdown (Online Figure IVB). Many of these genes encode proteins related to the regulation of signal transduction and anatomical structure size (Online Figure IVC). A total of 143 genes downregulated in CryABR120G-expressing cells were upregulated by Ube2v1 knockdown (Online Figure IVD). Many of these genes are related to programmed cell death, positive regulation of phosphate metabolism, regulation of blood vessel size, positive regulation of signaling, protein modification pathways and cardiovascular system development (Online Figure IVE). We also compared the gene expression patterns between R120G vs CTR and RADV1 vs CTR. The heat map revealed that Ube2v1 overexpression resulted in a gene expression profile that largely mimicked the patterns observed for AdCryABR120G-expressing NRVMs (Online Figure IVF). Of these 165 differentially expressed genes between these comparisons (Online Table II), 55 genes were upregulated (Online Figure IVG) and 107 genes were downregulated in both R120G- and RADV1-treated cells compared with CTR (Online Figure IVH). Bioinformatic analyses showed that genes with decreased expression were enriched for functional terms related to sprouting angiogenesis, positive regulation of signaling, regulation of the mitogen activated protein kinase cascade, regulation of the response to hypoxia, and developmental regulation (Online Figure IVI).

Comparing the 107 downregulated genes with the upregulated genes from RSIV1 versus R120G, we identified 26 overlapping genes that potentially could be regulated by Ube2v1 (Figure 7A). Kelch-like protein 40 (Klhl40) is involved in protein ubiquitination while OTU deubiquitinase 1 (Otud1) participates in the removal of ubuiquitin groups. Both Klhl40 and Otud1 expression are decreased in CryABR120G-expressing cells but expression is partially restored by Ube2v1 knockdown (Online Figure VA), while Ube2v1 overexpression has no the effect on CryABR120G-mediated expression changes for the two proteins (Online Figure VA). Intriguingly, Klhl40 was identified as a muscle-specific regulator, and its deletion led to sarcomere defects and muscle dysfunction.41 Otud1 specifically deubiquitinates K63-linked polyubiquitin chains.42 CryAB transcript and protein levels (Online Figure VA and VB) were not altered by manipulating Ube2v1 expression, consistent with the hypothesis that Ube2v1 may regulate protein aggregation via post-translational modification.

Figure 7. Ube2v1-regulated K63 ubiquitination promotes CryABR120G-induced protein aggregation.

A, Venn diagram showing the total common gene numbers and the overlap as indicated. CTR; untreated, control NRVMs, RSIV1; AdGFP-CryABR120G infection followed by siUbe2v1 transfection, RADV1; coinfection with AdGFP-CryABR120G and AdUbe2v1-myc. B, NRVMs were infected with either AdGFP-CryABWT or AdGFP-CryABR120G, the cells lysed after 5 days and the protein lysates immunoprecipitated with K63-ubiquitinated antibody and subsequently immunoblotted with CryAB antibody. Normal IgG antibody was used as a control. C, Western blot showing insoluble K63-ubiquitinated proteins with α-actinin used as a loading control. Scr; scrambled siRNA control, siv1; siUbe2v1. D, Western blot showing insoluble K63-ubiquitinated protein levels in NRVMs coinfected with AdUbe2v1-myc and AdGFP-CryABR120G. α-actinin was used as a loading control. E, NRVMs were coinfected with AdGFP-CryABR120G and the different ubiquitin mutant adenoviruses. At 5 days post-infection, NRVMs were fixed and immunostained with troponin I (TnI; red) and DAPI (nuclear staining; blue). Scale bar=100 μm. F, Aggregates in NRVMs were quantitated using NIS-elements software. At least 100 cells per group were quantitated. G, Quantitation of aggregate area in NRVMs coinfected with AdGFP-CryABR120G and the different ubiquitin mutant adenoviruses as well as with scrambled (Scramble) or siUbe2v1. At least 100 cells per group were quantitated using NIS-elements software. H, Aggregates in NRVMs coinfected with AdGFP-CryABR120G and the different ubiquitin mutant adenoviruses as well as AdUbe2v1-myc were quantitated using NIS-elements software. At least 100 cells per group were quantitated. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparisons for F. Two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparisons for G and H. Data are shown as mean±SEM. ns; non-significant (P>0.05). WT; AdGFP-CryABWT, R120G; AdGFP-CryABR120G.

Ube2v1 is required for Ube2n-catalyzed K63-linked ubiquitination of target proteins but by itself, Ube2v1 lacks this function.26, 27 Moreover, K63-linked ubiquitination may promote the formation of intracellular protein inclusions associated with neurodegenerative diseases.43 To determine whether K63 ubiquitination is involved in the progression of cardiac protein aggregation in the CryABR120G cardiomyocytes, we compared CryAB K63 ubiquitination in CryABWT and CryABR120G NRVMs using co-immunoprecipation analyses. The data revealed that CryAB could be ubiquitinated via K63 linkage in CryABR120G infected cells, but not in CryABWT infected cells (Figure 7B, arrow), suggesting that CryAB was a direct target of K63 ubiquitination and K63 ubiquitination might be important for aggregate formation. Decreasing Ube2v1 expression by siRNA knockdown decreased insoluble K63 ubiquitinated proteins (Figure 7C) while Ube2v1 overexpression enhanced K63 ubiquitination levels in the insoluble fraction (Figure 7D). To determine if increased K63 ubiquination promoted protein aggregation, we constructed wild-type and K48, K63, K48R, K63R ubiquitin mutant adenoviruses (Online Figure VC). NRVMs were coinfected with GFP-CryABR120G adenovirus and adenoviruses containing the ubiquitin mutants. Immunostaining showed that K63 and K48R ubiquitin mutants significantly enhanced aggregate formation, while K63R showed decreased aggregation compared with wild-type ubiquitin (Figure 7E and 7F), indicating that K63 ubiquitination promotes formation of protein aggregates in the CryABR120G-infected NRVMs. Knocking down Ube2v1 in CryABR120G-expressing NRVMs significantly decreased aggregate formation regardless of wild-type or mutant ubiquitin expression (Figure 7G). Furthermore, in Ube2v1-deficient cells, K63 ubiquitination still increased aggregate loads compared with uninfected cells (Figure 7G). Overexpressing Ube2v1 increased protein aggregates, while K63R mutation inhibited Ube2v1 overexpression-promoted aggregate formation in CryABR120G-expressing cells (Figure 7H). Taken together, our data suggest that Ube2v1 mediates protein aggregate formation partially through K63 ubiquitination.

Ube2v1 deletion inhibits protein aggregation in the mouse heart, improves cardiac function, and prolongs lifespan.

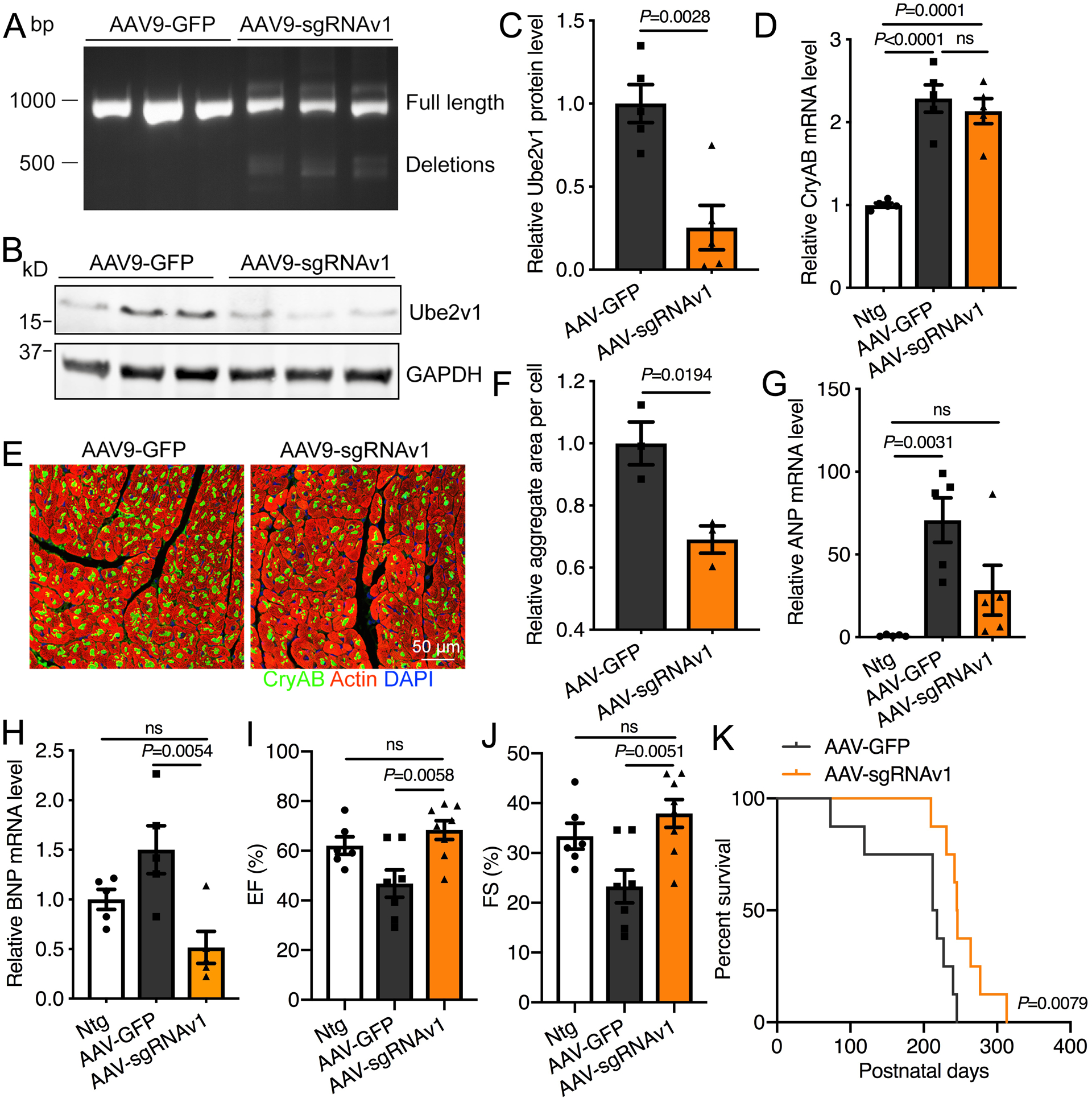

CryABR120G Tg mice were used to determine if the inhibitory effects of Ube2v1 on protein aggregation observed in vitro could be recapitulated in vivo. To delete Ube2v1 in the mouse heart, we utilized the CRISPR/Cas9 gene-editing platform to generate genomic deletions of specific exons for targeted gene correction.44 We designed 4 different gRNA sequences to bind sequences in two introns flanking exon 2 (Online Figure VIA) and made the corresponding AAV (Online Figure VIB). Cardiac-specific Ube2v1 knockout mice were generated by injecting AAV9-sgRNAv1 into Myh6-Cas9; CryABR120G double Tg mice at postnatal 10 day, and hearts were analyzed at different ages (Online Figure VIC). All the mice were healthy without any obvious cardiac abnormalities. As detected by touchdown PCR of the genomic DNA from these hearts, the expected genomic deletions were only present in AAV9-sgRNAv1 injected hearts (Figure 8A). Ube2v1 knockout efficiency was subsequently confirmed by Western blot with Ube2v1 antibody, with protein levels reduced by approximately 75% (Figure 8B and 8C). Consistent with in vitro data, CryAB mRNA levels in CryABR120G Tg mice were not altered by Ube2v1 deletion (Figure 8D). In the 9-week-old CryABR120G Tg mice, visible aggregates were immunostained with CryAB (Figure 8E). CryAB-positive aggregate areas were significantly decreased by Ube2v1 ablation (Figure 8E and F), indicating that Ube2v1 knockdown was also effective in vivo. Consistent with these data, we checked the molecular hypertrophic markers, atrial natriuretic peptide (ANP) and brain natriuretic peptide (BNP). Transcripts for both factors were increased in the CryABR120G hearts, while Ube2v1 knockdown decreased those RNAs to normal, or near normal levels (Figure 8G and 8H). To determine the impact of Ube2v1 ablation on cardiac function, echocardiography was performed at 6 months-of-age. Both ejection fraction and fractional shortening assessment showed cardiac function in CryABR120G Tg mice was significantly improved by Ube2v1 knockdown (Figure 8I and 8J). Ube2v1 deletion also prolonged the lifespan of CryABR120G Tg mice for one more month (Figure 8K). Collectively, our in vitro and in vivo experiments demonstrate that inhibition of Ube2v1 effectively lessens aberrant protein aggregation induced by CryABR120G, delaying the onset of cardiac failure and increasing lifespan in the face of a cardiac proteinopathy.

Figure 8. Knockout of Ube2v1 alleviates protein aggregation and normalizes cardiac function in CryABR120G Tg hearts.

A, Touchdown PCR across the exon 2 locus in heart-derived samples. The top band at 913bp represents the expected position of full-length PCR amplicons and the lower, 500 bp band represents the expected position of PCR products with deletions caused by the indicated sgRNA combinations. B, Western blot showing Ube2v1 knockout efficiency. C, Quantitation of the Western blot data. D, CryAB transcript levels were determined by real-time PCR. E, Representative images showing aggregates in the heart. Scale bar=50 μm. F, Aggregates in NRVMs were quantitated using NIS-elements software. At least 10 fields per group were quantitated. n=3 per group (two males and one female for AAV-GFP, one male and two females for AAV-sgRNAv1). G and H, The transcript levels of both ANP and BNP were determined by real-time PCR. n=5 per group (two males and three females per group). I and J, Measurement of ejection fraction (EF) (panel I) and fractional shortening (FS) (panel J) by echocardiography in 6-month old mice. n=6–8 per group (two males and four females for Ntg, three males and four females for AAV-GFP, three males and five females for AAV-sgRNAv1). K, Kaplan-Meier survival curves of R120G; Myh6-Cas9 mice injected with control AAV9-GFP or AAV9-sgRNAv1. n=8 per group (three males and five females for AAV-GFP, four males and four females for AAV-sgRNAv1). Unpaired, two-tailed Student’s t-test for C and F. One-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc multiple comparisons for D, G, H, I and J. Log-rank test for K. Data are shown as mean±SEM. ns; non-significant (P>0.05). Ntg; non-transgenic, AAV-GFP; R120G; Myh6-Cas9 mice injected with AAV9-GFP, AAV-sgRNAv1; R120G; Myh6-Cas9 mice injected with AAV9-sgRNAv1.

DISCUSSION

Using an unbiased, total genome high throughput screening approach, we identified Ube2v1 as a potentially important effector in modulating protein aggregation.33 The screen identified several hundred candidates that significantly affected CryABR120G-induced protein aggregation in mouse cardiomyocytes.33 We chose multiple genes related to protein ubiquitination for validation, from which a specific ubiquitin conjugating E2 enzyme family, including Ube2v1, Ube2v2 and Ube2n attracted our interest. There are essentially no data bearing on these proteins’ cardiac function. However, the ubiquitin conjugating E2 enzyme Ube2n is known to mediate K63-specific protein ubiquitination and plays important roles in various cellular processes such as the inflammatory response.45 Ube2n requires Ube2v1 or Ube2v2 (MMS2) as a co-factor to exert its full activity,25, 27 but the full spectrum of actions that these proteins, or protein complexes can play is diverse and largely unexplored. For example, the heterodimer Ube2n-Ube2v1 is required for nuclear factor κB activation, whereas Ube2n-Ube2v2 is involved in the DNA damage response.46 It was recently reported that Ube2n overexpression increased the aggregation of mutant huntingtin and depletion of Ube2n attenuated huntingtin aggregation, suggesting a critical role for Ube2n in this neurodegenerative disease,47 while other studies have implicated Ube2v1 as a potential proto-oncogene.26 Our data confirm Ube2v1 can modulate CryABR120G-induced protein aggregation in both cardiomyocyte cell cultures and in the intact heart, improving cardiac function during the mid-stage of adulthood and significantly prolonging life during proteotoxic disease, although all the mice eventually succumb to cardiac failure. K63-linked ubiquitination was positively modulated by Ube2v1 and accompanied increased protein aggregation. Enhanced UPS performance by Ube2v1 knockdown augmented degradation of the misfolded, ubiquitinated proteins. However, the direct mechanistic relationship between K63 ubiquitination and UPS performance remains undefined.

Enhanced aggregation by CryABR120G expression is largely blocked by Ube2v1 knockdown, while overexpression of Ube2v1 promoted aggregate formation. Our current study shows that, in the CryABR120G model, Ube2v1 knockdown is therapeutically effective in inhibiting protein aggregation and cardiomyocyte hypertrophy, leading to a relative improvement in cardiac function, despite continuing CryABR120G-expression. Different forms of protein ubiquitination target proteins to different fates.48 For example, K48-linked polyubiquitination of target proteins is the canonical signal for their degradation by the proteasome.49 UPS-mediated protein degradation requires two main steps: protein polyubiquitination and subsequent proteasomal cleavage.50 We showed that Ube2v1 knockdown decreased ubiquitinated protein conjugate levels in CryABR120G expressing NRVMs in the absence of altered proteasome activity. These data point to Ube2v1 knockdown exerting at least some of its effects by altering proteasomal flux in an as yet undefined manner. Consistent with this hypothesis, in transfected cells Ube2v1 overexpression resulted in increased GFPu levels, indicating impaired UPS performance. While it remains unclear as to how Ube2v1 affects UPS performance, Wang et al. previously showed that increased accumulation of CryAB aggregates, which is a consequence of increased Ube2v1 expression (Figure 3), inhibits proteasomal function, presumably by blockage of the entry pore.36 Therefore, it is likely that Ube2v1 exerts its effects on UPS performance indirectly. That is, knockdown of Ube2v1 decreases CryAB aggregation, largely normalized the expression levels of genes associated with proteasomal structure, and therefore maintained normal proteasomal flux.

Our existing data support the hypothesis that Ube2v1 is also a positive regulator of cardiac protein aggregation partially through K63 ubiquitination. The noncanonical K63-linked polyubiquitination of target proteins is usually associated with lysosome activity, intracellular signaling and DNA repair, contributing to the development of various disorders including cancer, diabetic nephropathy and neurodegeneration.43, 51–53 A lack of PIK3C3 (phosphatidylinositol 3-kinase catalytic subunit type 3, also known as Vps34) impaired endosomal sorting complexes required for transport-mediated protein sorting and autophagy by preventing K63-ubiquitinated CryAB from normal cargo sorting and degradation through autophagy.54 As a result, aggregates containing K63-ubiquitinated CryAB are formed, causing hypertrophic cardiomyopathy in the absence of Vps34.54 K63 ubiquitination also promoted the formation of inclusions and aggregates associated with neurodegenerative disorders. These aggregates may be selectively degraded via autophagy.43, 55 Consistently, CryAB was ubiquitinated via a K63 linkage in CryABR120G-expressing cardiomyocytes. As autophagic flux is impaired in the CryABR120G hearts, enhancing K63 levels led to aggregate accumulation. Importantly, Ube2v1 appears to function in K63 ubiquitination of CryAB, because knockdown of Ube2v1 disrupted K63 ubiquitination and inhibited K63’s effect on protein aggregation. Decreased Ube2v1 levels led to decreased K63-ubiquitinated protein, resulting in decreased aggregate load that, in turn, allowed proteasomal function to be better maintained in the face of continuing CryABR120G-induced proteotoxicity. It may be that Ube2v1 knockdown decreases protein K63 ubiquitination, potentially directing the cell’s degradative machinery away from the impaired autophagic pathway towards the UPS. That system might then be better able to handle the initial misfolded protein load, but formal testing of this hypothesis remains the subject of future experimentation.

The autophagic processes by which aggregates are cleared play an important role in cardiomyocyte protein quality control.9, 20 However, autophagic activity appears to be unaffected by Ube2v1 levels and does not contribute to the protective function of Ube2v1 knockdown against cardiomyocyte proteotoxicity. Decreased Ube2v1 inhibits CryABR120G-induced protein aggregation, which is associated with enhanced UPS performance and diminished K63-linked protein ubiquitination. Clinically, cardiac proteinopathy is apparent in patients with a subset of cardiac diseases, including desmin-related cardiomyopathy. If it is left untreated, increased proteotoxic stress leads to heart failure. In the present study, knocking out Ube2v1 improves cardiac outcomes in CryABR120G-induced cardiac proteinopathy. The AAV9-sgRNAv1 illustrates a proof of principle gene therapy approach for this proteinopathy and, if validated in larger animal models of proteotoxicity, could potentially become clinically relevant.

Supplementary Material

NOVELTY AND SIGNIFICANCE.

What Is Known?

Compromised protein structure and intracellular protein aggregates in the heart may lead to cardiac disease and heart failure.

Enhanced ubiquitin-proteasome system and autophagy can help to remove misfolded and aggregated proteins. One example is αB-crystallin (CryAB)R120G-based desmin-related cardiomyopathy.

Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 variant 1 (Ube2v1) forms a heterodimer with ubiquitin conjugating enzyme E2 N (Ube2n), which catalyzes synthesis of Lys (K) 63-linked ubiquitination in some cancer cell types.

What New Information Does This Article Contribute?

Myocardial Ube2v1 is increased in the mouse model of cardiac proteinopathy and positively regulates protein aggregation.

Ube2v1 modulates the ubiquitin-proteasome system performance separate from autophagy.

K63-linked ubiquitination is altered by the manipulation of Ube2v1 and contributes to protein aggregate formation.

Ube2v1 knockout by adeno-associated virus (AAV) 9-delivered single guide RNA improves cardiac outcomes in the mouse model of CryABR120G proteinopathy.

Cardiac proteinopathy is a feature of a large subset of heart diseases, including desmin-related cardiomyopathy. However, there is no current medical therapy targeting proteotoxicity to treat cardiac disease. Here, we identify a novel role of Ube2v1 in regulating protein aggregate formation both in cultured cardiomyocytes and in the intact heart. We report that Ube2v1 modulates ubiquitin proteasome system performance and K63-linked ubiquitination, contributing to the protein aggregation. We show a novel strategy of Ube2v1 knockout specially in cardiomyocytes by AAV9-mediated delivery. Ube2v1 deficiency reduces aggregate loads in the mouse model of CryABR120G induction and improves cardiac performance with increased lifespan in vivo. This effective gene therapy approach targeting Ube2v1 represents a new therapeutic strategy with clinical implications for the treatment of cardiac diseases with increased proteotoxic stress.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We would like to thank Sithara Raju Ponny (Division of Human Genetics at Cincinnati Children’s Hospital Medical Center) for the assistance with RNA sequencing data analysis.

SOURCES OF FUNDING

This work was supported by NIH grants P01HL69779, P01HL059408, R01HL05924, R011062927, a Trans-Atlantic Network of Excellence grant from Le Fondation Leducq (Robbins).

Nonstandard Abbreviations and Acronyms:

- AAV

adeno-associated virus

- AdGFPu

adenovirus containing GFPu

- AdGFP-CryABWT

adenovirus containing wild-type CryAB tagged with GFP

- AdGFP-CryABR120G

adenovirus containing CryABR120G tagged with GFP

- AdUbe2v1-myc

adenovirus containing Ube2v1 with c-Myc tag

- CryAB

αB-crystallin

- CryABWT

wild-type αB-crystallin

- CryABR120G

R120G mutation of αB-crystallin

- CTR

control

- DAPI

4’,6-diamidino-2-phenylindole

- GFP

green fluorescent protein

- GFPu

the degron tagged with GFP

- K63

lysine 63

- LC3-II

microtubule-associated light chain-II

- NRVMs

neonatal rat ventricular myocytes

- PQC

protein quality control

- RADV1

coinfection with AdGFP-CryABR120G and AdUbe2v1-myc

- RSIV1

AdGFP-CryABR120G infection followed by siUbe2v1 transfection

- Scr

scramble

- siRNA

small interfering RNA

- sgRNA

single guide RNA

- TnI

troponin I

- Ube2v1

ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme E2 variant 1

- UPS

ubiquitin-proteasome system

Footnotes

REFERENCES

- 1.Wyatt AR, Yerbury JJ, Ecroyd H, Wilson MR. Extracellular chaperones and proteostasis. Annu Rev Biochem. 2013;82:295–322 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Labbadia J, Morimoto RI. The biology of proteostasis in aging and disease. Annu Rev Biochem. 2015;84:435–464 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kim YE, Hipp MS, Bracher A, Hayer-Hartl M, Hartl FU. Molecular chaperone functions in protein folding and proteostasis. Annu Rev Biochem. 2013;82:323–355 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Sanbe A, Osinska H, Saffitz JE, Glabe CG, Kayed R, Maloyan A, Robbins J. Desmin-related cardiomyopathy in transgenic mice: A cardiac amyloidosis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004;101:10132–10136 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gianni D, Li A, Tesco G, McKay KM, Moore J, Raygor K, Rota M, Gwathmey JK, Dec GW, Aretz T, Leri A, Semigran MJ, Anversa P, Macgillivray TE, Tanzi RE, del Monte F. Protein aggregates and novel presenilin gene variants in idiopathic dilated cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2010;121:1216–1226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Gouveia M, Xia K, Colon W, Vieira SI, Ribeiro F. Protein aggregation, cardiovascular diseases, and exercise training: Where do we stand? Ageing Res Rev. 2017;40:1–10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang ZV, Hill JA. Protein quality control and metabolism: Bidirectional control in the heart. Cell Metab. 2015;21:215–226 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Pattison JS, Sanbe A, Maloyan A, Osinska H, Klevitsky R, Robbins J. Cardiomyocyte expression of a polyglutamine preamyloid oligomer causes heart failure. Circulation. 2008;117:2743–2751 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gupta MK, McLendon PM, Gulick J, James J, Khalili K, Robbins J. Ubc9-mediated sumoylation favorably impacts cardiac function in compromised hearts. Circ Res. 2016;118:1894–1905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Su H, Li J, Zhang H, Ma W, Wei N, Liu J, Wang X. Cop9 signalosome controls the degradation of cytosolic misfolded proteins and protects against cardiac proteotoxicity. Circ Res. 2015;117:956–966 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zheng H, Tang M, Zheng Q, Kumarapeli AR, Horak KM, Tian Z, Wang X. Doxycycline attenuates protein aggregation in cardiomyocytes and improves survival of a mouse model of cardiac proteinopathy. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2010;56:1418–1426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wang X, Robbins J. Heart failure and protein quality control. Circ Res. 2006;99:1315–1328 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sandri M, Robbins J. Proteotoxicity: An underappreciated pathology in cardiac disease. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2014;71:3–10 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Henning RH, Brundel B. Proteostasis in cardiac health and disease. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2017;14:637–653 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Ranek MJ, Zheng H, Huang W, Kumarapeli AR, Li J, Liu J, Wang X. Genetically induced moderate inhibition of 20s proteasomes in cardiomyocytes facilitates heart failure in mice during systolic overload. J Mol Cell Cardiol. 2015;85:273–281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hayashi M, Imanaka-Yoshida K, Yoshida T, Wood M, Fearns C, Tatake RJ, Lee JD. A crucial role of mitochondrial hsp40 in preventing dilated cardiomyopathy. Nat Med. 2006;12:128–132 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Pattison JS, Osinska H, Robbins J. Atg7 induces basal autophagy and rescues autophagic deficiency in cryabr120g cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2011;109:151–160 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gupta MK, Gulick J, Liu R, Wang X, Molkentin JD, Robbins J. Sumo e2 enzyme ubc9 is required for efficient protein quality control in cardiomyocytes. Circ Res. 2014;115:721–729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ranek MJ, Terpstra EJ, Li J, Kass DA, Wang X. Protein kinase g positively regulates proteasome-mediated degradation of misfolded proteins. Circulation. 2013;128:365–376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bhuiyan MS, Pattison JS, Osinska H, James J, Gulick J, McLendon PM, Hill JA, Sadoshima J, Robbins J. Enhanced autophagy ameliorates cardiac proteinopathy. J Clin Invest. 2013;123:5284–5297 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Duncan EJ, Cheetham ME, Chapple JP, van der Spuy J. The role of hsp70 and its co-chaperones in protein misfolding, aggregation and disease. Subcell Biochem. 2015;78:243–273 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Arosio P, Michaels TC, Linse S, Mansson C, Emanuelsson C, Presto J, Johansson J, Vendruscolo M, Dobson CM, Knowles TP. Kinetic analysis reveals the diversity of microscopic mechanisms through which molecular chaperones suppress amyloid formation. Nat Commun. 2016;7:10948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lim J, Yue Z. Neuronal aggregates: Formation, clearance, and spreading. Dev Cell. 2015;32:491–501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.van Wijk SJ, Timmers HT. The family of ubiquitin-conjugating enzymes (e2s): Deciding between life and death of proteins. FASEB J. 2010;24:981–993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Eddins MJ, Carlile CM, Gomez KM, Pickart CM, Wolberger C. Mms2-ubc13 covalently bound to ubiquitin reveals the structural basis of linkage-specific polyubiquitin chain formation. Nat Struct Mol Biol. 2006;13:915–920 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wu Z, Shen S, Zhang Z, Zhang W, Xiao W. Ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme complex uev1a-ubc13 promotes breast cancer metastasis through nuclear factor-small ka, cyrillicb mediated matrix metalloproteinase-1 gene regulation. Breast Cancer Res. 2014;16:R75. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pulvino M, Liang Y, Oleksyn D, DeRan M, Van Pelt E, Shapiro J, Sanz I, Chen L, Zhao J. Inhibition of proliferation and survival of diffuse large b-cell lymphoma cells by a small-molecule inhibitor of the ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme ubc13-uev1a. Blood. 2012;120:1668–1677 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cheng J, Fan YH, Xu X, Zhang H, Dou J, Tang Y, Zhong X, Rojas Y, Yu Y, Zhao Y, Vasudevan SA, Zhang H, Nuchtern JG, Kim ES, Chen X, Lu F, Yang J. A small-molecule inhibitor of ube2n induces neuroblastoma cell death via activation of p53 and jnk pathways. Cell Death Dis. 2014;5:e1079. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.McLendon PM, Robbins J. Desmin-related cardiomyopathy: An unfolding story. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2011;301:H1220–1228 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Willis MS, Patterson C. Proteotoxicity and cardiac dysfunction--alzheimer’s disease of the heart? N Engl J Med. 2013;368:455–464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wang X, Osinska H, Klevitsky R, Gerdes AM, Nieman M, Lorenz J, Hewett T, Robbins J. Expression of r120g-alphab-crystallin causes aberrant desmin and alphab-crystallin aggregation and cardiomyopathy in mice. Circ Res. 2001;89:84–91 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Maloyan A, Sanbe A, Osinska H, Westfall M, Robinson D, Imahashi K, Murphy E, Robbins J. Mitochondrial dysfunction and apoptosis underlie the pathogenic process in alpha-b-crystallin desmin-related cardiomyopathy. Circulation. 2005;112:3451–3461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.McLendon PM, Davis G, Gulick J, Singh SR, Xu N, Salomonis N, Molkentin JD, Robbins J. An unbiased high-throughput screen to identify novel effectors that impact on cardiomyocyte aggregate levels. Circ Res. 2017;121:604–616 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Carroll KJ, Makarewich CA, McAnally J, Anderson DM, Zentilin L, Liu N, Giacca M, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. A mouse model for adult cardiac-specific gene deletion with crispr/cas9. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2016;113:338–343 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Xu N, Bitan G, Schrader T, Klarner FG, Osinska H, Robbins J. Inhibition of mutant alphab crystallin-induced protein aggregation by a molecular tweezer. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen Q, Liu JB, Horak KM, Zheng H, Kumarapeli AR, Li J, Li F, Gerdes AM, Wawrousek EF, Wang X. Intrasarcoplasmic amyloidosis impairs proteolytic function of proteasomes in cardiomyocytes by compromising substrate uptake. Circ Res. 2005;97:1018–1026 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Dong X, Liu J, Zheng H, Glasford JW, Huang W, Chen QH, Harden NR, Li F, Gerdes AM, Wang X. In situ dynamically monitoring the proteolytic function of the ubiquitin-proteasome system in cultured cardiac myocytes. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2004;287:H1417–1425 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Sanbe A, Yamauchi J, Miyamoto Y, Fujiwara Y, Murabe M, Tanoue A. Interruption of cryab-amyloid oligomer formation by hsp22. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:555–563 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Meng L, Mohan R, Kwok BH, Elofsson M, Sin N, Crews CM. Epoxomicin, a potent and selective proteasome inhibitor, exhibits in vivo antiinflammatory activity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1999;96:10403–10408 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Zheng Q, Su H, Ranek MJ, Wang X. Autophagy and p62 in cardiac proteinopathy. Circ Res. 2011;109:296–308 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Garg A, O’Rourke J, Long C, Doering J, Ravenscroft G, Bezprozvannaya S, Nelson BR, Beetz N, Li L, Chen S, Laing NG, Grange RW, Bassel-Duby R, Olson EN. Klhl40 deficiency destabilizes thin filament proteins and promotes nemaline myopathy. J Clin Invest. 2014;124:3529–3539 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Yao F, Zhou Z, Kim J, Hang Q, Xiao Z, Ton BN, Chang L, Liu N, Zeng L, Wang W, Wang Y, Zhang P, Hu X, Su X, Liang H, Sun Y, Ma L. Skp2- and otud1-regulated non-proteolytic ubiquitination of yap promotes yap nuclear localization and activity. Nat Commun. 2018;9:2269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Tan JM, Wong ES, Kirkpatrick DS, Pletnikova O, Ko HS, Tay SP, Ho MW, Troncoso J, Gygi SP, Lee MK, Dawson VL, Dawson TM, Lim KL. Lysine 63-linked ubiquitination promotes the formation and autophagic clearance of protein inclusions associated with neurodegenerative diseases. Hum Mol Genet. 2008;17:431–439 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Ousterout DG, Kabadi AM, Thakore PI, Majoros WH, Reddy TE, Gersbach CA. Multiplex crispr/cas9-based genome editing for correction of dystrophin mutations that cause duchenne muscular dystrophy. Nat Commun. 2015;6:6244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Wu X, Karin M. Emerging roles of lys63-linked polyubiquitylation in immune responses. Immunol Rev. 2015;266:161–174 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Andersen PL, Zhou H, Pastushok L, Moraes T, McKenna S, Ziola B, Ellison MJ, Dixit VM, Xiao W. Distinct regulation of ubc13 functions by the two ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme variants mms2 and uev1a. J Cell Biol. 2005;170:745–755 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Yin P, Tu Z, Yin A, Zhao T, Yan S, Guo X, Chang R, Zhang L, Hong Y, Huang X, Zhou J, Wang Y, Li S, Li XJ. Aged monkey brains reveal the role of ubiquitin-conjugating enzyme ube2n in the synaptosomal accumulation of mutant huntingtin. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:1350–1362 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Clague MJ, Heride C, Urbe S. The demographics of the ubiquitin system. Trends Cell Biol. 2015;25:417–426 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Su H, Wang X. The ubiquitin-proteasome system in cardiac proteinopathy: A quality control perspective. Cardiovasc Res. 2010;85:253–262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang X, Pattison JS, Su H. Posttranslational modification and quality control. Circ Res. 2013;112:367–381 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Nathan JA, Kim HT, Ting L, Gygi SP, Goldberg AL. Why do cellular proteins linked to k63-polyubiquitin chains not associate with proteasomes? EMBO J. 2013;32:552–565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Yan K, Ponnusamy M, Xin Y, Wang Q, Li P, Wang K. The role of k63-linked polyubiquitination in cardiac hypertrophy. J Cell Mol Med. 2018;22:4558–4567 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pontrelli P, Conserva F, Papale M, Oranger A, Barozzino M, Vocino G, Rocchetti MT, Gigante M, Castellano G, Rossini M, Simone S, Laviola L, Giorgino F, Grandaliano G, Di Paolo S, Gesualdo L. Lysine 63 ubiquitination is involved in the progression of tubular damage in diabetic nephropathy. FASEB J. 2017;31:308–319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Kimura H, Eguchi S, Sasaki J, Kuba K, Nakanishi H, Takasuga S, Yamazaki M, Goto A, Watanabe H, Itoh H, Imai Y, Suzuki A, Mizushima N, Sasaki T. Vps34 regulates myofibril proteostasis to prevent hypertrophic cardiomyopathy. JCI Insight. 2017;2:e89462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Bhat KP, Yan S, Wang CE, Li S, Li XJ. Differential ubiquitination and degradation of huntingtin fragments modulated by ubiquitin-protein ligase e3a. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111:5706–5711 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Lim KL, Chew KC, Tan JM, Wang C, Chung KK, Zhang Y, Tanaka Y, Smith W, Engelender S, Ross CA, Dawson VL, Dawson TM. Parkin mediates nonclassical, proteasomal-independent ubiquitination of synphilin-1: Implications for lewy body formation. J Neurosci. 2005;25:2002–2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Duan Y, Ma G, Huang X, D’Amore PA, Zhang F, Lei H. The clustered, regularly interspaced, short palindromic repeats-associated endonuclease 9 (crispr/cas9)-created mdm2 t309g mutation enhances vitreous-induced expression of mdm2 and proliferation and survival of cells. J Biol Chem. 2016;291:16339–16347 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Sadayappan S, de Tombe PP. Cardiac myosin binding protein-c: Redefining its structure and function. Biophys Rev. 2012;4:93–106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.