Abstract

Sexually transmitted infections (STI), including Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae, have reached record high rates in the United States. Sexually transmitted infections disproportionately affect reproductive-aged women 15 to 44 years old, who account for 65% and 42% of the total reported C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae cases, respectively. Undiagnosed STIs can result in serious health complications that put women at an increased risk for pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, and tubal factor infertility. Many of these women are seen by physicians (e.g., obstetrician–gynecologists, family medicine doctors, pediatricians) or other clinicians (e.g., nurse practitioners, midwives, physician assistants) who care for women. These clinicians have the opportunity to help curb the continued increase in STI incidence rates with the implementation and use of expedited partner therapy. Expedited partner therapy is a proven effective health care practice that allows clinicians to give patients medications or prescriptions to distribute to their partners. Despite expedited partner therapy’s proven effectiveness, there are barriers to its implementation that must be understood in order to enhance STI treatment and prevention efforts. In this commentary, we discuss these barriers, and appeal to women’s health clinicians to implement or increase use of expedited partner therapy for the management of women with STIs and their sexual partners.

Précis:

Implementation of expedited partner therapy by women’s health clinicians will decrease the burden and effects of sexually transmitted infections and related morbidity in women.

Introduction

The incidence rates of sexually transmitted infections (STI), such as Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae, reached record highs in 2017 after demonstrated increases over the prior three years1. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), there were over 1.7 million reported cases of C. trachomatis and over 555,000 cases of N. gonorrhoeae in 2017—resulting in increases of 6.8% and 18.5%, respectively, since 2016.1

The majority of C. trachomatis infections affect young women (ages 15–24), who accounted for 45% of the total reported cases in 2017.1 Reproductive-aged women (ages 15–44) accounted for 65% and 42% of the total reported C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae cases, respectively, in 2017.1 The CDC estimates that the reported STI incidence rates are underestimated because many cases are undiagnosed, which may lead to STI-related sequelae. In women, undiagnosed, recurrent, or persistent STIs may result in deleterious reproductive health complications like pelvic inflammatory disease, ectopic pregnancy, tubal factor infertility, chronic pelvic pain, and HIV acquisition.1 Early data suggest that 40–70% of male partners are untreated.2 The sequelae of untreated STIs in men includes urethritis, scarring of the reproductive tract, epididymitis, and possible infertility. Rarely, disseminated gonococcal infection may occur.1

Reproductive Health Visits

With many reproductive-aged women receiving obstetrics and gynecology (OB/GYN) care, those visits are an opportunity to discuss sexual and reproductive health. OB/GYN care providers should improve and enhance their understanding of the impact that undiagnosed, persistent, or repeat STIs have on reproductive health. Emerging evidence demonstrates an increased risk of pelvic inflammatory disease among women with repeated C. trachomatis infections. In a retrospective cohort of military women, Bautista et al. found the hazard of pelvic inflammatory disease increased by 22% (95% CI = 13%, 32%, P<0.001) for each additional diagnosis of C. trachomatis compared to women with a single diagnosis.3 These findings make it imperative for clinicians to help reduce the incidence rates of STIs by providing education, screening, and treatment of the initial infection, and deploying efforts to prevent recurrent infections. Expedited partner therapy allows clinicians to give patients medications or prescriptions to distribute to their sexual partners. As a proven effective STI treatment and prevention strategy, expedited partner therapy has the potential to fill a needed gap in clinical practice. C. trachomatis incidence rates have grown significantly faster in expedited partner therapy prohibitive states compared to expedited partner therapy permissible states.4

The Practice of Expedited Partner Therapy

The CDC supports clinicians in the treatment of sexual partners of individuals diagnosed with C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoeae, as do the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, American Academy of Family Physicians, American Academy of Pediatrics, American Medical Association, and Society for Adolescent Health and Medicine. While expedited partner therapy is permissible in 43 states in the union and ‘potentially allowable’ in five states (SD, KS, OK, AL, NJ) and Puerto Rico, it is currently prohibited in South Carolina and Kentucky.2,5 Expedited partner therapy may also be used for trichomoniasis depending on state and local health department guidelines.2 However, the studies on expedited partner therapy for trichomoniasis are conflicting. While one randomized clinical trial (RCT) showed partner therapy decreased repeat infections among infected women,6 two other RCTs showed either no effect or borderline effect.7,8

Expedited partner therapy is not intended as a first-line partner management strategy, but as a useful alternative when the partner is unable or unlikely to seek care in a timely fashion. Some of the reasons partners may not engage in care include: 1) lack of health insurance; 2) privacy/confidentiality concerns; 3) access to clinical care; and 4) cost or availability of prescription medications.9–11 Economic analysis indicates that expedited partner therapy is a cost-saving and cost-effective STI partner management strategy, specifically amongst adolescents.12 Several studies have demonstrated that expedited partner therapy is a safe and effective method of preventing persistent or recurrent STIs.4,13

Given limited financial resources and the increasing burden of STIs, clinicians or public health field investigators may not be able to notify sexual partners of possible C. trachomatis and N. gonorrhoeae exposure.14,15 As a result, many clinicians have resorted to standard partner referral for treatment of sexual partners, which relies on the index patient notifying their partner(s) about the newly diagnosed STI and the need for evaluation and treatment by a clinician. This is a suboptimal method for ensuring partner therapy, as it results in the treatment of only 36% of male partners in heterosexual relationships.2 Expedited partner therapy improves the notification of sexual partners and increases the confidence of the index partner that his or her partner(s) received treatment.13,16 There is an added benefit of patient privacy, as the index patient is not required to provide partner names and is able to obtain the needed number of expedited partner therapy prescriptions or medications for all partners. Despite the proven benefits of expedited partner therapy, however, small studies have shown low uptake in clinician usage,17,18 including Rosenfeld, et al., who found that about 11% of health care providers used expedited partner therapy consistently.17

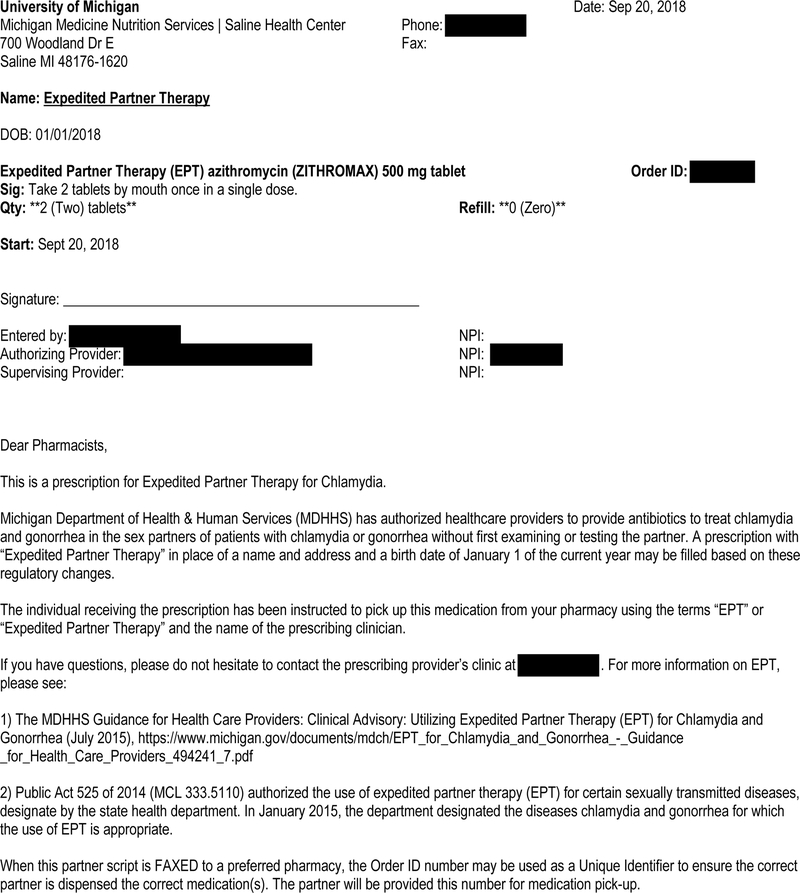

Expedited partner therapy can be delivered in one of two ways: 1) delivery of prescriptions to the sexual partner(s) by the index patient; or 2) delivery of medications to the sexual partner(s) by the index patient.19 Prescriptions may be delivered electronically or by fax to a preferred pharmacy. Each expedited partner therapy–permissible state issues guidance on the delivery of expedited partner therapy prescriptions. For example, in some states such as Michigan, “Expedited Partner Therapy” should be written on the name line and “January 1, of the current year” may be written on the date of birth line (Figure 1).20 Educational materials and resources related to STI screening, treatment, and possible drug-related adverse reactions should be delivered by the index patient or pharmacists at the time of medication pick-up. Pharmacists can play a key role in coordinating the delivery of expedited partner therapy and also have the opportunity to verify the sexual partner’s allergies and provide them with reproductive health education.21

Figure 1.

University of Michigan expedited partner therapy prescription from MiChart, the University of Michigan’s electronic medical record. Some text has been redacted for privacy.

All sexual partners in the past 60 days, or the most recent sexual partner(s) prior to diagnosis, should be considered at risk for infection and can be offered treatment.2 To help ensure that proper treatment was provided and that re-infection has not occurred, it is important to remember to retest women at three months.22 Of note, expedited partner therapy is not routinely recommended for use among men who have sex with men, or in the following situations: 1) when patients may be co-infected with syphilis or HIV; 2) in cases of suspected child abuse or sexual assault; 3) in situations where a patient’s safety is in question; 4) for partners with known allergies to STI treatment antibiotics; and 5) in cases of pharyngeal or rectal C. trachomatis or N. gonorrhoeae infection.2

The Expedited Partner Therapy Debate

Medical decision-making requires clinicians to continually weigh the benefits against the risks when offering STI management recommendations to patients—expedited partner therapy is no different. The expedited partner therapy debate includes a discussion of the following concerns: 1) the medical duty to treat an STI; 2) possible concerns related to intimate partner violence due to a recently diagnosed STI; and 3) concerns associated with providing care for an individual who has not been evaluated by a clinician (Table 1).

Table 1.

The Expedited Partner Therapy Debate

| Pros | Cons |

|---|---|

| Provides sexual partner treatment | Limited screening for STIs in sexual partners |

| Improved access to care and convenience for sexual partners | Limited provision of care for men in OB/GYN clinics |

| Decreased cost associated with recurrent and persistent STIs | Potential, albeit rare, severe, life-threatening allergic reactions |

| Decreased incidence of recurrent STIs | Pharmacists refusal to fill EPT prescription |

| Decreased STI-related morbidity* | Unclear payer† of partner therapy via EPT prescription |

| Targets male partners that are often asymptomatic and may not access care | Risk of intimate partner violence |

STI: sexually transmitted infection; EPT: expedited partner therapy

Pelvic inflammatory disease, infertility, chronic pelvic pain, ectopic pregnancy

Insurance vs. out-of-pocket

Adverse reactions are rare, as the recommended expedited partner therapy treatment regimens are highly effective single-dose medications.23 The majority are taken orally and the most commonly reported adverse reaction is mild gastrointestional intolerance.2,23,24 Severe reactions, including anaphylaxis, to medications prescribed as expedited partner therapy do not have reported percentages due to their rarity.25 California, the first state to implement the use of expedited partner therapy, created a hotline to report any allergic reactions, and none had been received as of January 2016.23

Amidst growing concern about drug-resistant N. gonorrhoeae infection, the CDC recommends dual therapy with ceftriaxone 250 milligrams intramuscularly plus azithromycin 1 gram orally for uncomplicated N. gonorrhoeae infections of the cervix, urethra, and rectum in the index patient. A dual regimen is also advised for expedited partner therapy, but it consists of an oral cephalosporin (cefixime 400 milligrams) plus azithromycin 1 gram orally.26 In 2017, susceptibility testing for ceftriaxone found 0.2% of isolates with an elevated minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC); for cefixime, there were 0.4% of isolates with an elevated MIC.1 Dual therapy helps to ensure a clinical cure, prevents further drug resistance, and is recommended for individuals diagnosed with N. gonorrhoeae infection, even if the C. trachomatis test was negative at the time of diagnosis.26

There are concerns regarding payment for expedited partner therapy medications. Most health insurance plans cover recommended preventive services, including annual HIV and STI testing, based on U.S. Preventive Services Taskforce recommendations.27,28 The medications for the sexual partner(s) can be self-paid by the index patient or the partner(s), but the pharmacy should not bill a partner’s medication under the index patient’s health insurance plan.

A major concern of clinicians pertaining to the use of expedited partner therapy rests in liability and malpractice protection. The American Bar Association supports expedited partner therapy and the removal of legal barriers.29 A national review of expedited partner therapy malpractice litigation revealed that no active or pending lawsuits from a third party directed at clinicians have gone to court,30,31 although a lack of reported litigation does not mean liability claims have not occurred or been settled out of court. Furthermore, each state varies in protection, with some states explicitly protecting clinicians while others do not.5

Even after being provided with correct prescriptions, issues can occur once a sexual partner gets to the pharmacy.10 There is a concern that pharmacists who are unfamiliar or uncomfortable with expedited partner therapy prescriptions will refuse to fill them, which can lead to increased stigma and limited healthcare access for individuals seeking care.18 Clinicians must always consider the possibility of intimate partner violence with every case and address this as a priority, as over one-third of women will experience intimate partner violence in their lifetime.32 A small-sample study found that nearly one-third of clinicians had not considered the need to assess for intimate partner violence when providing STI treatment to their patients.32

Future Directions and Research Priorities

Optimizing the clinical implementation of expedited partner therapy will improve care for index patients and their sexual partners. The clinical trials demonstrating effectiveness of expedited partner therapy dispensed medications from clinical sites, whereas in clinical practice, the most common method of expedited partner therapy delivery is by prescription.9 The variance in research and clinical practice should be evaluated to understand how to best implement expedited partner therapy and support patients, along with their sexual partners, in STI treatment and prevention. Additional trials are needed to evaluate the process of prescribing, filling, and picking up electronic expedited partner therapy prescriptions given the increased use of electronic medical record (EMR) systems.33 Currently, some expedited partner therapy–permissible states are experiencing challenges tracking the use of expedited partner therapy by clinicans. This may be achieved successfully by integrating ‘EPT Smart Sets’ into EMRs to improve treatment delivery (Figure 1). Despite the need for additional research to address some clinical unknowns, expedited partner therapy should still be offered given its proven effectiveness and cost savings, and because patients prefer it.12

Call to Action: Reproductive Clinicians

It is imperative that a woman’s sexual health is assessed at each visit, specifically amongst those of reproductive age—15–44 years. An appropriate sexual history (e.g., the Five P’s: Partners, Practices, Prevention of pregnancy, Protection from STIs, and Past history of STIs) should be obtained by reproductive health clinicians.19 The answers to these questions will help to guide education on sexual health. During these visits, clinicians should be aware of their personal perspectives and judgments pertaining to STIs and the patient’s sexual behaviors in order to prevent stigmatization.34 STI-related stigma that individuals encounter from clinicians and their community may keep them from disclosing their sexual behaviors and practices, which may consequently prevent them from seeking and receiving the care and services they need.34 Improving the clinician-patient relationship will help to decrease STI-related stigma and the perceptions that inhibit quality care.

After obtaining a positive STI test result for a patient, clinicians should provide notification and treatment, discuss expedited partner therapy, and arrange for retesting. They may also offer support for notifying the patient’s sexual partner(s). Web-based platforms (e.g., www.inspot.org and www.stdcheck.com) may also offer assistance with anonymous notification of sexual partners. Collaboration with local public health departments along with community STI prevention organizations can be valuable in treating STIs. These community collaborations may help ease the burden by providing education and resources that may not be feasible for many reproductive clinicians to offer. The provision of barrier methods (e.g., male and female condoms) in the office, when permissible by state legislation or health system policies, may also prevent persistent or recurrent STIs. Finally, collaboration with local pharmacies is vital to the acceptance of expedited partner therapy in the community. Partnering with pharmacists may ensure that the allergies of sexual partners are verified, expedited partner therapy prescriptions are filled, and educational materials are provided.

Discussion

Those who provide reproductive healthcare to women serve an important role in safeguarding their health and curbing the increasing incidence of STIs in the United States. This can be achieved by protecting them from STI-related morbidity with appropriate screening and treatment of STIs using all currently available options, including expedited partner therapy.

Speaking with a woman about her sexual health at every visit will encourage a healthy clinician-patient relationship and allow for increased education and screening opportunities. Offering expedited partner therapy to women as an STI treatment strategy may help decrease the likelihood of persistent or recurrent STIs, as well as STI-related morbidity. Clinicians should familiarize themselves with the permissibility of expedited partner therapy and the protections offered to them by referencing the legal status of expedited partner therapy in their state.5 As champions of reproductive healthcare, we must be willing to use all available tools—including expedited partner therapy—to protect women, or be prepared to treat the consequences they will face from the next report of record-breaking STI incidence rates.

Acknowledgments

Funding:

Cornelius D. Jamison received funding from the National Clinician Scholars Program and the United States Department of Veterans Affairs supporting his role as a National Clinician Scholar. Jenell S. Coleman received funding from the National Institutes of Health under grant R01 HD092013. The funders played no role in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the report; or the decision to submit the report for publication.

Footnotes

Financial Disclosure

Each author has confirmed compliance with the journal’s requirements for authorship.

The authors did not report any potential conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Sexually Transmitted Disease Surveillance 2017. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/std/stats17/. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- 2.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Expedited Partner Therapy in the management of sexually transmitted diseases. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/treatment/eptfinalreport2006.pdf. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- 3.Bautista CT, Hollingsworth BP, Sanchez JL. Repeat Chlamydia Diagnoses Increase the Hazard of Pelvic Inflammatory Disease among U.S. Army females: A Retrospective Cohort Analysis. Sex Transm Dis 2018;45(11):770–773. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mmeje O, Wallett S, Kolenic G, Bell J. Impact of expedited partner therapy (EPT) implementation on chlamydia incidence in the USA. Sex Transm Infect 2081;94(7):545–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Legal Status of Expedited Partner Therapy (EPT). Available at https://www.cdc.gov/std/ept/legal/default.htm. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- 6.Lyng J, Christensen J. A double-blind study of the value of treatment with a single dose tinidazole of partners to females with trichomoniasis. Acta Obstet Gynecol Scand 1981;60(2):199–201. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kissinger P, Schmidt N, Mohammed H, Leichliter JS, Gift TL, Meadors B, et al. Patient-delivered partner treatment for Trichomonas vaginalis infection: a randomized controlled trial. Sex Transm Dis 2006;33(7):445–50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Schwebke JR, Desmond RA. A randomized controlled trial of partner notification methods for prevention of trichomoniasis in women. Sex Transm Dis 2010;37(6):392–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Schillinger JA, Gorwitz R, Rietmeijer C, Golden MR. The expedited partner therapy continuum: a conceptual framework to guide programmatic efforts to increase partner treatment. Sex Transm Dis 2016;43(2S):S63–75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jamison CD, Chang T, Mmeje O. Expedited Partner Therapy: Combating Record High Sexually Transmitted Disease Rates. Am J Public Health 2018;108(10):1325–1327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Qin JZ, Diniz CP, Coleman JS. Pharmacy-level Barriers in Implementing Expedited Partner Therapy in Baltimore, Maryland. Am J Obstet Gynecol 2018;218(5):504.e1–504.e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gift TL, Kissinger P, Mohammed H, Leichliter JS, Hogben M, Golden MR. The Cost and Cost-Effectiveness of Expedited Partner Therapy Compared With Standard Partner Referral for the Treatment of Chlamydia or Gonorrhea. 2011;38(11):1067–1073. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Golden MR, Whittington WL, Handsfield HH, Hughes JP, Stamm WE, Hogben M, et al. Effect of expedited treatment of sex partners on recurrent or persistent gonorrhea or chlamydial infection. N Engl J Med 2005;352(7):676–685. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Golden MR, Hogben M, Handsfield HH, Lawrence JS, Potterat JJ, Holmes KK. Partner notification for HIV and STD in the United States: low coverage for gonorrhea, chlamydial infection, and HIV. Sex Transm Dis. 2003;30(6):490–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rahman MM, Khan M, Gruber D. A Low-Cost Partner Notification Strategy for the Control of Sexually Transmitted Diseases: A Case Study From Louisiana. Am J Public Health 2015;1675–1680. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Golden MR, Kerani RP, Stenger M, Hughes JP, Aubin M, Malinski C, et al. Uptake and population-level impact of expedited partner therapy (EPT) on Chlamydia trachomatis and Neisseria gonorrhoeae: the Washington State community-level randomized trial of EPT. PLoS Med 2015;12(1):e1001777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rosenfeld EA, Marx J, Terry MA, Stall R, Flatt J, Borrero S, et al. Perspectives on expedited partner therapy for chlamydia: a survey of health care providers. Int J STD AIDS 2016;27(13):1180–1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Taylor MM, Reilley B, Yellowman M, Anderson L, de Ravello L, Tulloch S. Use of expedited partner therapy among chlamydia cases diagnosed at an urban Indian health centre, Arizona. Int J STD AIDS 2013;24(5):371–374. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Clinical Prevention Guidance. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/clinical.htm. Retrieved October 1, 2018.

- 20.Michigan Department of Health and Human Services Bureau of Local Health and Administrative Services Division of Health, Wellness and Disease Control STD Section -- July 2015 Guidance for Health Care Providers Expedited Partner Therapy (EPT) For Chlamydia and Gonorrhea. Available at: https://www.michigan.gov/documents/mdch/EPT_for_Chlamydia_and_Gonorrhea_-_Guidance_for_Health_Care_Providers_494241_7.pdf. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- 21.Hilverding AT, DiPietro Mager NA. Pharmacists’ attitudes regarding provision of sexual and reproductive health services. J Am Pharm Assoc (2003) 2017;57(4):493–497. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Chlamydial Infections in Adolescents and Adults. Available at https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/chlamydia.htm. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- 23.California Department of Public Health Sexually Transmitted Diseases (STD) Control Branch, California STD Controllers Association, California Prevention Training Center (CAPTC). Patient-Delivered Partner Therapy (PDPT) for Chlamydia, Gonorrhea, and Trichomoniasis: Guidance for Medical Providers in California. Available at:https://www.cdph.ca.gov/Programs/CID/DCDC/CDPH%20Document%20Library/ClinicalGuidelines_CA-STD-PDPT-Guidelines.pdf. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- 24.Maryland Department of Health and Mental Hygiene. Expedited Partner Therapy (EPT) for Chlamydia and Gonorrhea: Guide for Health Care Providers in Maryland. Available at: https://phpa.health.maryland.gov/OIDPCS/CSTIP/CSTIPDocuments/Maryland%20EPT%20Provider%20Guide_June%202016%20FINAL2.pdf. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- 25.Medscape. Drug information for Azithromycin, Cefixime, and Metronidazole. Available at: https://reference.medscape.com/drug/zithromax-zmax-azithromycin-342523#4. Retrieved August 3, 2018.

- 26.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. 2015. Sexually Transmitted Diseases Treatment Guidelines. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/tg2015/default.htm. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- 27.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. STD & HIV Screening Recommendations. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/prevention/screeningreccs.htm. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- 28.Kaiser Family Foundation. Payment and Coverage for Prevention of Sexually Transmitted Infections (STIs). Available at: https://www.kff.org/womens-health-policy/fact-sheet/payment-and-coverage-for-the-prevention-of-sexually-transmitted-infections-stis/. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- 29.American Bar Association. Resolution supporting removal of legal barriers to the provision of EPT, August 11–12, 2008. Available at: https://www.americanbar.org/content/dam/aba/directories/policy/2008_am_116a.authcheckdam.pdf. Retrieved November 14, 2018.

- 30.Arizona State University Sandra Day O’Connor College of Law, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Legal/Policy Toolkit for Adoption and Implementation of Expedited Partner Therapy. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/std/ept/legal/ept-toolkit-complete.pdf. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- 31.Legislature Nebraska. Senate Debate concerning EPT. Available at: http://update.legislature.ne.gov/?p=11069. Retrieved August 30, 2018.

- 32.Rosenfeld EA, Marx J, Terry MA, Stall R, Pallatino C, Borrero S, Miller E. Intimate partner violence, partner notification, and expedited partner therapy: a qualitative study Int J STD AIDS 2016;27(8):656–661. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Okah E, Arya V, Rogers M, Kim M, Schillinger JA. Sentinel Surveillance for Expedited Partner Therapy Prescriptions Using Pharmacy Data, in 2 New York City Neighborhoods, 2015. Sex Transm Dis 2017;44(2):104–108. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Ivanski C, Kohut T. Exploring definitions of sex positivity through thematic analysis. Can J Hum Sex 2017;26(3):216–225. [Google Scholar]