Abstract

Objective

To describe the clinical, serologic and histologic features of a cohort of patients with brachio-cervical inflammatory myopathy (BCIM) associated with systemic sclerosis (SSc) and unravel disease-specific pathophysiologic mechanisms occurring in these patients.

Methods

We reviewed clinical, immunologic, muscle MRI, nailfold videocapillaroscopy, muscle biopsy, and response to treatment data from 8 patients with BCIM-SSc. We compared cytokine profiles between patients with BCIM-SSc and SSc without muscle involvement and controls. We analyzed the effect of the deregulated cytokines in vitro (fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and muscle cells) and in vivo.

Results

All patients with BCIM-SSc presented with muscle weakness involving cervical and proximal muscles of the upper limbs plus Raynaud syndrome, telangiectasia and/or sclerodactilia, hypotonia of the esophagus, and interstitial lung disease. Immunosuppressive treatment stopped the progression of the disease. Muscle biopsy showed pathologic changes including the presence of necrotic fibers, fibrosis, and reduced capillary number and size. Cytokines involved in inflammation, angiogenesis, and fibrosis were deregulated. Thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1), which participates in all these 3 processes, was upregulated in patients with BCIM-SSc. In vitro, TSP-1 and serum of patients with BCIM-SSc promoted proliferation and upregulation of collagen, fibronectin, and transforming growth factor beta in fibroblasts. TSP-1 disrupted vascular network, decreased muscle differentiation, and promoted hypotrophic myotubes. In vivo, TSP-1 increased fibrotic tissue and profibrotic macrophage infiltration in the muscle.

Conclusions

Patients with SSc may present with a clinically and pathologically distinct myopathy. A prompt and correct diagnosis has important implications for treatment. Finally, TSP-1 may participate in the pathologic changes observed in muscle.

Brachio-cervical inflammatory myopathy (BCIM) is characterized by weakness of proximal muscles of the upper limbs and cervical flexor and/or extensor muscles.1 There are less than 30 cases described in the literature so far.1–3 In most of them, myositis was associated with other immune-mediated disorders such as myasthenia gravis, rheumatoid arthritis, or mixed connective tissue disease.

Systemic sclerosis (SSc) is an immune-mediated rheumatic disease characterized by fibrosis of the skin and internal organs and vasculopathy.4 The prevalence of musculoskeletal involvement in SSc is not completely known and varies from 13% to 96% depending on the series published.5–10 Muscle weakness in patients with SSc, when present, involves proximal muscles of the upper and lower limbs, and it is associated with higher disability, worse prognosis, and death.11 Brachio-cervical weakness is the presenting symptom in few patients with SSc.3,12

The pathogenic mechanism behind BCIM is unknown, but findings on muscle biopsies, consistent with a necrotizing myopathy associated with fibrosis, macrophage and B-cell infiltrates, and complement deposition, suggest that specific pathways—different from those of the other inflammatory myopathies—are likely involved.1,13

We report the clinical and pathologic features and response to treatment of a cohort of patients with BCIM associated with SSc from our center and the role of thrombospondin-1 (TSP-1) in the pathogenesis of this disease.

Methods

Patients

Muscle biopsies from patients with BCIM-SSc (n = 8), dermatomyositis (DM; n = 3), and immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy (IMNM; n = 3) were obtained for diagnostic purposes. Healthy muscle samples were obtained from patients undergoing orthopedic surgery. All patients with BCIM-SSc fulfilled the 2013 European League Against Rheumatism (EULAR) and American College of Rheumatology (ACR) classification criteria EULAR/ACR for SSc.14 Muscle strength before treatment and at last visit was studied using the Medical Research Council scale. We analyzed cervical flexion, bilateral shoulder abduction, bilateral elbow flexion, and bilateral elbow extension. The score was from 0 to 5 per each item, with a maximum accumulative score of 35 points. Genomic DNA was extracted and processed for human leukocyte antigen (HLA) genotyping as previously described.15

Standard protocol approvals, registrations, and patient consents

The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of the Hospital de la Santa Creu i Sant Pau in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration. Informed consent and the authorization to publish their photographs were obtained from participants.

Cytokine measurements

Serum samples were obtained from our cohort of patients with BCIM-SSc, patients with SSc with no evidence of muscle involvement (n = 4), and age and sex-matched controls (n = 23). Serum samples were analyzed using the Proteome Profiler Human XL Cytokine Array Kit (R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN) according to the manufacturer's protocol. Quantitative analysis of blotting spot was performed using Image Studio 5.2 (LI-COR, Lincoln, NE). TSP-1 levels were measured in serum samples using a commercial ELISA kit (R&D Systems).

Cell cultures

Human myoblasts and fibroblasts were isolated and cultured from control muscle biopsies and enriched using magnetic separation with CD56 magnetic beads (Miltenyi Biotec, Bergisch-Gladbach, Germany) as previously described.16 We analyzed the proliferation of fibroblasts incubated with 5 μg/mL of recombinant TSP-1 (R&D Systems) or serum from controls or patients with BCIM-SSc for 48 hours (dilution 1/6) by BrdU incorporation assay (Roche, Indianapolis, IN). The effect of TSP-1 in muscle differentiation was evaluated by the measurement of fusion index after 5 days with daily treatment of TSP-1 at 2, 5, or 10 μg/mL or serum from controls and patients with BCIM-SSc (dilution ¼) in Dulbecco's Modified Eagle Medium 2% fetal bovine serum. To measure whether TSP-1 and BCIM-SSc serum induced myotube hypotrophy, we added TSP-1 (20 μg/mL) or BCIM-SSc serum (dilution ¼) for 48 hours, and we compared myotube area using myosin heavy chain staining (clone MF20; Hybridoma bank, IA) with nontreated or control serum. We performed tube formation assays in human umbilical vein endothelial cells incubated with TSP-1 (10 μg/mL) or serum samples (dilution ½) from controls and patients with BCIM-SSc as previously described.17 Five pictures per well at different time points were analyzed using the Macro Angiogenesis Analyzer (Gilles Carpentier. Contribution: Angiogenesis Analyzer, ImageJ News, October 5, 2012) for NIH ImageJ 1.47v.

Statistics

Statistical analyses were performed with GraphPad Software (GraphPad Software, La Jolla, CA). The Fisher exact test, OR, and CI calculations were performed. Values are expressed as mean ± standard error of the mean of triplicates. Comparisons and multiple comparisons were made using the Mann-Whitney test or 2-way analysis of variance, respectively. Correlations were studied with the Pearson coefficient (r). Differences were considered significant when p < 0.05.

Data availability

Data presented in this study are available on reasonable request.

Supplementary methods (e-methods, links.lww.com/NXI/A213) can be downloaded. Primary and secondary antibodies used in the study are listed in table e-1. mRNA specific probes used for qPCR studies are listed in table e-2.

Results

Patients with BCIM-SSc present a homogeneous clinical picture

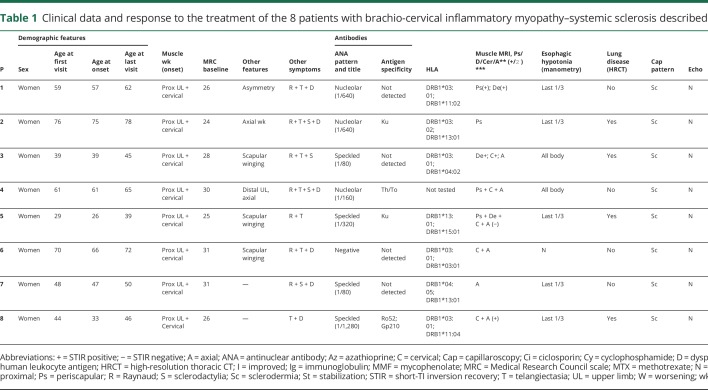

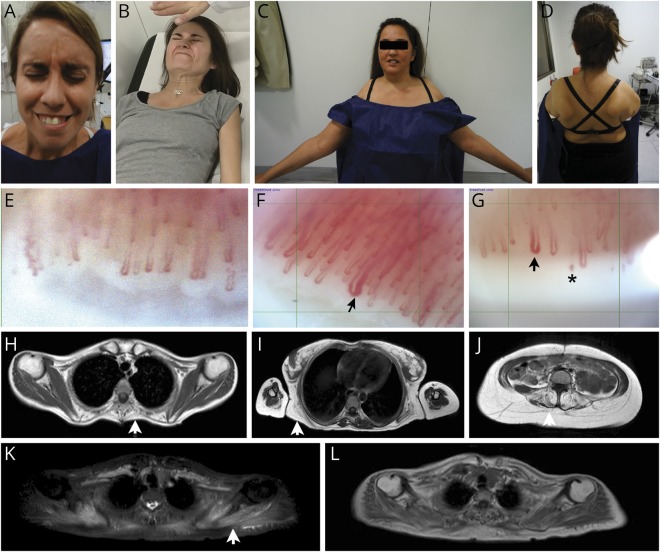

We studied 8 patients (all female), who were referred to our Unit because of subacute or chronic muscle weakness involving cervical and proximal muscles of the upper limbs (table 1). Six of the 8 had been diagnosed previously of muscle dystrophy based in the clinical and muscle biopsy results. However, next-generation sequencing studies did not identify any pathologic variant in 169 genes related to muscle dystrophy, and facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy had been ruled out using specific genetic testing. All patients but one had also Raynaud syndrome, and in all cases, concomitant telangiectasia and sclerodactilia were found (figure 1). All cases had pathologic nailfold videocapillaroscopy and hypotonia of the esophagus, and 50% of patients had interstitial lung disease by high-resolution thoracic CT, associated with a restrictive pattern in the lung function test. All these symptoms were identified after the first visit in our center, and none of the patients had a previous diagnosis of SSc. Muscle MRI demonstrated fatty replacement in cervical and periscapular muscles in all the cases. Short-TI inversion recovery muscles MRI sequences showed hyperintense signal in at least 1 muscle in 50% of the cases. Echocardiography was normal in all patients. HLA study showed a high prevalence of the allele HLA-DRB1*03:01 (4/7; OR = 4.2, CI = 2.29–7.7), and curiously, the other 3 patients were HLA-DRB1*13:01 (OR = 4.6, CI = 2.3–9.2). We detected antinuclear antibodies in serum in all patients but one, although the pattern and antigen specificity were variable, as shown in table 1. All patients but one had a good response to different regimens of immunosuppressors, which consisted in an improvement of muscle weakness or a stabilization of the disease. Table 1 illustrates the different treatment regimens used and the progression of the disease. It is noteworthy that none of the patients recovered muscle weakness completely; in fact, scapular winging, when present, did not improve, and therefore limitation to extend the arms persisted over time.

Table 1.

Clinical data and response to the treatment of the 8 patients with brachio-cervical inflammatory myopathy–systemic sclerosis described in this study

Figure 1. Clinical findings in patients with BCIM-SSc.

Facial weakness (A), prominent cervical weakness (B), proximal upper limb weakness with deltoid atrophy (C), and bilateral scapular winging (D). Nailfold videocapillaroscopy: normal findings in healthy control (E), early active scleroderma pattern showing giant loops (arrow) in patient 1 and normal number of capillaries in patient 5 (F). Active scleroderma pattern showing giant loops (arrow), microhemorrhages (asterisk), and loss of capillaries in patient 1 (G). Muscle MRI: T1-weighted sequence shows fatty replacement of the periscapular muscles affecting rhomboid major (H), latissimus dorsi and serratus anterior (I), and lumbar paraspinal muscles (J). STIR sequence (K) shows signal enhancement in scapular muscles that appear normal in T1-weighted sequence (L). Arrow shows fatty replacement in thoracic paraspinal muscles (H), serratus Anterior (I) and Lumbar paraspinal muscles (J). Arrow shoes STIR + signal in periscapular muscles (K), which do not have fat replacement yet (L). BCIM = brachio-cervical inflammatory myopathy; SSc = systemic sclerosis; STIR = short-TI inversion recovery.

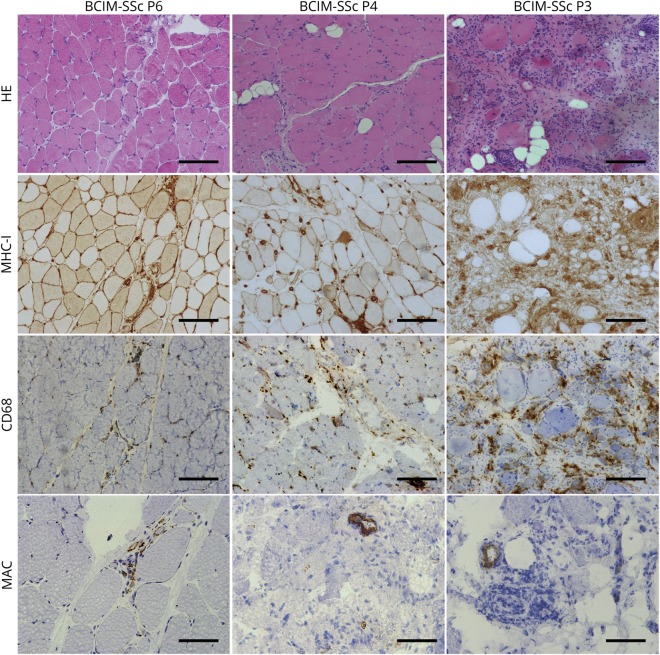

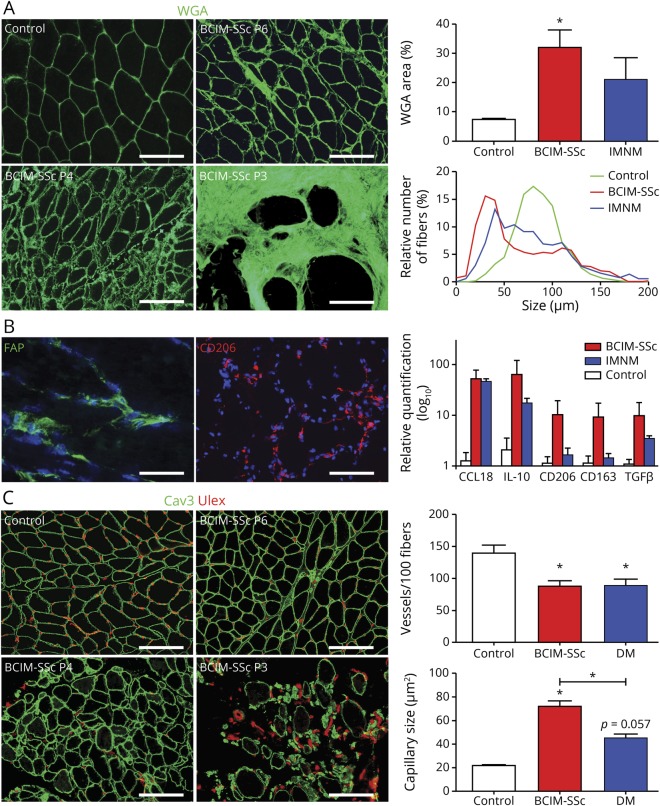

BCIM-SSc muscle biopsies show inflammation, fibrosis, and vasculopathy

Muscle biopsies showed increased myofiber size variability, abundant atrophic myofibers, and necrosis. Diffuse major histocompatibility complex class I expression and CD68 macrophages infiltrates were found in all biopsies (figure 2). CD20, CD4, and CD8 infiltrates were found in 3/8, 2/8, and 5/8 of the patients, respectively (figure e-1, links.lww.com/NXI/A210). Complement deposition (membrane attack complex) was observed in vessels in 50% of patients (figure 2). The quantification of pathologic findings showed a significant increase in fibrotic tissue and a significant decrease in myofiber size in patients with BCIM-SSc compared with controls. These changes were similar to those observed in some patients with IMNM (figure 3A). We identified fibroblasts positive for the fibroblast-activated protein embedded in the connective tissue. Macrophages were positive for CD206 marker, which are typically found in a profibrotic and necrotizing environment, and quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) showed the upregulation of the M2 markers CCL18, interleukin-10, CD206, CD163, and transforming growth factor beta (TGFβ) (figure 3B). The number of vessels was reduced, which was smaller in patients with BCIM-SSc compared with controls, similar to DM samples (figure 3C). There was a gradient in macrophage infiltration, fibrosis, and in the number of vessels related to the severity of the muscle disease (figures 2 and 3).

Figure 2. Histochemical and immunohistochemical analysis of muscle biopsies from patients with BCIM-SSc.

Representative pictures of HE, MHC-I, CD68, and MAC (C5b9) stainings in 3 patients with BCIM-SSc with mild (P6), moderate (P4), and severe (P3) muscle pathology are shown. Scale bar (HE, MHC-I, and CD68): 200 μm; scale bar (MAC): 100 μm. BCIM = brachio-cervical inflammatory myopathy; HE = hematoxilin-eosin; MAC membrane attack complex; MHC = major histocompatibility complex; SSc = systemic sclerosis.

Figure 3. Muscle biopsies from patients with BCIM-SSc are characterized by fibrosis, inflammation, and vasculopathy.

Amount of fibrotic tissue stained by WGA and muscle fiber size frequency were quantified and compared among controls, patients with BCIM-SSc, and patients with IMNM. Scale bar: 200 μm (A). Immunofluorescence of the FAP and CD206 in BCIM-SSc samples (scale bars: 100 μm and 200 μm, respectively) and qPCR gene expression analysis of muscle biopsies from patients with BCIM-SSc, patients with IMNM, and controls (B). Representative pictures of the quantification of the number and size of IM capillaries (Ulex) in control, BCIM-SSc, and dermatomyositis muscle biopsies. Three pictures of different patients with BCIM-SSc are shown with mild (P6), moderate (P4), and severe (P3) muscle pathology. Scale bar: 200 μm. *p < 0.05. BCIM = brachio-cervical inflammatory myopathy; DM = dermatomyositis; FAP = fibroblast-activated protein; IL = interleukin; IMNM = immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy; SSc = systemic sclerosis; TGF = transforming growth factor; WGA = wheat germ agglutinin.

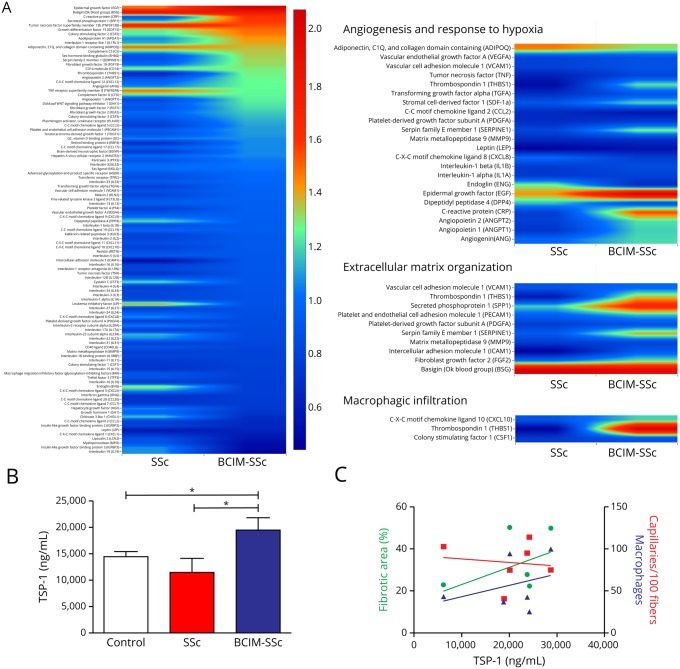

Circulating levels of TSP-1 are elevated in patients with BCIM-SSc and are associated with muscle pathologic findings

We examined the levels of 105 circulating cytokines in the serum of our cohort of patients with BCIM-SSc and compared them with patients with SSc with no myopathy and controls. We observed a cluster of deregulated cytokines in BCIM-SSc samples that are involved in angiogenesis and response to hypoxia (such as TSP-1, angiopoietin-2, and sCD105), extracellular matrix organization (such as TSP-1, fibroblast growth factor 2, and serpin), and macrophage infiltration (such as TSP-1 and CXCL10) (figure 4A). ELISA measurement confirmed that TSP-1, which participates in these 3 cellular processes, was significantly overexpressed in BCIM-SSc (figure 4B). qPCR showed high expression levels of TSP-1 in the BCIM-SSc muscle biopsies that, using immunohistochemistry, was found located in the extracellular matrix, in CD206+ macrophages, and in some vessels (figure e-2, links.lww.com/NXI/A211). Based in these results, we analyzed whether TSP-1 serum levels correlated with muscle pathology findings. Higher levels of TSP-1 were found in serum patients whose biopsies showed larger fibrotic areas, higher number of macrophages, and fewer capillaries (figure 4C). Overall, these results suggest that TSP-1 may participate in the muscle pathology of patients with BCIM-SSc.

Figure 4. TSP-1 is overexpressed in patients with BCIM-SSc, and it is related to muscle fibrosis, inflammation, and capillary loss.

Heatmap of the levels of cytokines measured by cytokine arrays in patients with BCIM-SSc and SSc normalized with healthy controls. Circulating molecules involved in angiogenesis, extracellular matrix, and macrophage infiltration are dysregulated in BCIM (A). TSP-1 levels measured by ELISA are overexpressed in patients with BCIM-SSc compared with patients with SSc and controls (B). TSP-1 levels positively correlate with fibrosis and number of macrophages in the muscle and negatively with the number of IM capillaries (C). *p < 0.05. BCIM = brachio-cervical inflammatory myopathy; SSc = systemic sclerosis; TSP-1 = thrombospondin-1.

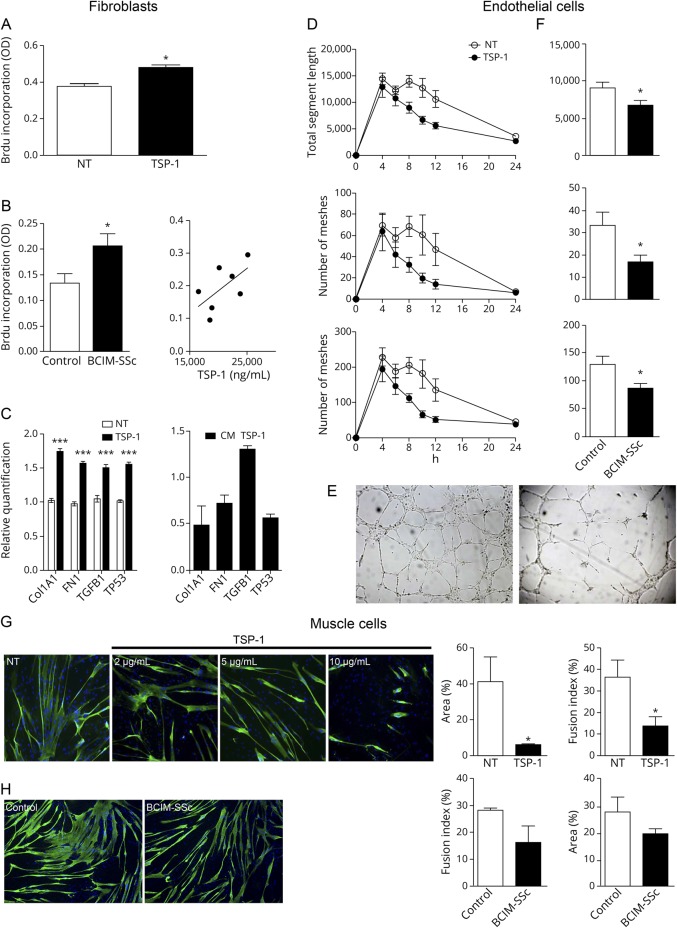

The effects of TSP-1 in human fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and muscle cells

We explored the role of recombinant TSP-1 and serum from BCIM-SSc in the expansion of fibrotic tissue. TSP-1 significantly increased the proliferation of human fibroblasts compared with nontreated cells (figure 5A). We observed the same effects when we incubated BCIM-SSc serum, and moreover, we found increased rates of fibroblast proliferation if TSP-1 serum levels were higher (figure 5B). qPCR studies showed that TSP-1 increased significantly the expression of the proliferation marker p53 and of the components of the extracellular matrix collagen I, fibronectin, and TGFβ. Moreover, TGFβ expression was also elevated when the supernatant of TSP-1–treated cells was transferred to untreated fibroblasts (figure 5C).

Figure 5. The effects of TSP-1 and BCIM-SSc serum in human fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and muscle cells.

Human fibroblasts cultured with recombinant TSP-1 increase cell proliferation (A). Serum from patients with BCIM-SSc increases fibroblast proliferation compared with serum from controls, and it is positively associated (r = 0.66; p = 0.1) with serum levels of TSP-1 (B). Gene expression analysis of fibroblasts incubated with TSP-1 (left) showing the upregulation of Collagen I (Col1A1), FN, TGFβ, and p53 (TP53). Supernatant of fibroblasts preincubated with TSP-1 (right) increases TGFβ gene expression (C). Time-lapse analysis of the tube formation assay with endothelial cells cultured with TSP-1 and measurements of total segment length, number of meshes, and junctions at different time points (D). Representative pictures of the tube formation assay without TSP-1 (NT; left) and the evident destruction of the vascular network with TSP-1 (right) (E). Tube formation assay performed with serum from healthy controls or patients with BCIM-SSc. Quantification of the parameters at 8 hours of culture is shown (F). Fusion index of differentiating myoblasts and area of mature myotubes were analyzed when TSP-1 (G) or serum from healthy controls or patients with BCIM-SSc was incubated (H). Data are represented as mean of at least 3 replicates ± standard error of the mean. *p < 0.05; ***p < 0.001. BCIM = brachio-cervical inflammatory myopathy; FN = fibronectin; NT = nontreated; SSc = systemic sclerosis; TGFβ = transforming growth factor beta; TSP-1 = thrombospondin-1.

We performed a tube formation assay using endothelial cells to analyze the effect of TSP-1 and BCIM-SSc serum in the formation of vascular network. Both untreated and cells incubated with TSP-1 showed formation of capillaries at 4 hours of culture. In the case of untreated cells, capillaries were stable until 12 hours of culture. In contrast, TSP-1 induced a rapid degeneration of the vascular network after 4 hours of culture (figure 5D) as shown in representative images (figure 5E). The addition of BCIM serum to the media produced similar results, we found a significant reduction of capillaries at 8 hours compared with controls (figure 5F).

When we studied the effect of TSP-1 or serum in muscle cells, we observed a significant reduction in the number and size of myotubes in a TSP-1 dose-dependent manner (figure 5G). When we incubated BCIM-SSc serum, we observed a similar trend, but differences were not statistically significant (figure 5H).

Effects of TSP-1 in vivo

Repeated intramuscular (IM) injection of TSP-1 in healthy mice induced a series of changes in skeletal muscle architecture. First, we observed persistent focal inflammatory infiltrates in the TSP-1–injected animals that were not present in the phosphate buffered saline-injected animals (figure e-3A, links.lww.com/NXI/A212). Flow cytometry confirmed the increased number of macrophages in the TSP-1–injected muscles that indeed showed markers of profibrotic M2 macrophages such as CD163 (figure e-3B). Quantification of fibrotic areas in the muscle showed a significant increase in the TSP-1–injected animals (figure e-3, A and C), whereas the quantification of the number of IM capillaries was not different from that observed in phosphate buffered saline-injected animals (data not shown). qPCR showed a significant upregulation of collagen III and interleukin-10, which participates in the switch of macrophages from M1 (proregenerative) to M2 (profibrotic). Moreover, we observed an upregulation of the endothelial marker Pecam1, which may reflect an early compensatory mechanism against vascular damage.

Discussion

In the present study, we describe a cohort of patients with a common clinical picture characterized by late-onset BCIM associated with SSc. These patients present not only muscle biopsy findings of an IMNM associated with an increase in fibrotic tissue but also a reduction of the number of vessels, which is frequently observed in the muscle biopsy of patients with DM. To further understand the pathologic process behind this syndrome, we have performed a series of experiments that led us to propose TSP-1 as a key factor involved in the development of the disease.

Muscle weakness preferentially involving cervical and proximal muscles of the upper limbs as an initial symptom is uncommon in neuromuscular disorders. The differential diagnosis should include hereditary but also acquired muscle disorders such as facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy, amyotrophic lateral sclerosis, and even myasthenia gravis.18,19 Inflammatory myopathies can also develop a similar phenotype, but in most patients with DM or polymyositis, weakness involves preferentially proximal muscles of the lower and upper limbs.20 Muscle weakness in patients with BCIM involves cervical muscles (extensor and/or flexor muscle) and proximal muscles of the upper limbs but can spread to other muscle groups involving paraspinal and respiratory muscles. The disease can sometimes progress slowly over several months, making the differential diagnosis with a muscle dystrophy more difficult. Patients with BCIM usually associate other inflammatory diseases such as rheumatoid arthritis, lupus, or mixed connective tissue disease, but the association with SSc has been reported in few cases only.1–3,12 Patients with SSc and myopathy have an important variability regarding clinical and histologic features. These patients may have just hyperCKemia or develop muscle weakness involving proximal muscles of the limbs. Muscle biopsy in these cases varies from the classic polymyositis phenotype to a fibrosing myopathy, including also nonspecific myositis or IMNM.11,13,21,22 This variability suggests that different mechanisms can be involved in the development of muscle damage in SSc. Our patients showed findings compatible with SSc: skin telangiectasia, Raynaud syndrome, esophageal dysfunction, and interstitial lung disease, and all of them fulfilled criteria for SSc.14 Muscle MRI showed fatty replacement in paraspinal and proximal muscles of the upper limbs, confirming that the development of symptoms was slowly progressive, although increase in short-TI inversion recovery signal was found in a few patients, suggesting the presence of active necrosis or inflammation in the muscle.23 The clinical picture of our patients was similar, suggesting a common pathophysiology, a notion that is reinforced by the muscle biopsy findings and the homogeneity of HLA haplotypes. HLA-DRB1*11 alleles have been associated with adult SSc in several studies within Caucasian populations, including Spanish populations.24 However, in our patients, we did not find these alleles, but we found a strong association with HLA-DRB1*03:01 (57.1%) and HLA-DRB1*13:01 (42.9%). The correct diagnosis of patients with BCIM as an acquired inflammatory myopathy is extremely important because the treatment can stabilize or improve muscle weakness and completely change progression of the disease, as we have observed in our cohort of patients (table 1).

All patients had a muscle biopsy showing necrosis, fibrosis, and reduced number of capillaries that ranged from mild to severe depending on the case. Our patients shared features with both IMNM (necrotic fibers and macrophages) and chronic DM and antisynthetase syndrome (fibrosis and damaged capillaries). In a thorough review by Stenzel et al.,25 antisynthetase syndrome is included as a subtype of IMNM with endo- and perimysial fibrous tissue. Also, overlap myositis is proposed as a fifth subtype of inflammatory muscle disease that is beginning to be recognized.20 We believe that our series of patients, with homogenous clinical features and a common HLA, could be classified in this subtype. We identified a deregulation of the expression of soluble factors involved in angiogenesis, macrophage infiltration, and extracellular matrix remodeling, which are common findings in the muscle biopsy of our patients. The vasculopathy observed in the muscle biopsies of patients with BCIM-SSc is supported by the different deregulated cytokines identified in our experiments. For example, we observed an upregulation of angiopoietin-2, which has been previously related to vessel destabilization26 and downregulation of sCD105, a marker of neovascularization, low levels of which are related to enhanced cellular responses to TGFβ.27 All patients had pathologic findings in nailfold videocapillaroscopy compatible with SSc. Nailfold videocapillaroscopy translates microvascular damage in SSc. We focused our attention on TSP-1 because (1) serum levels of this cytokine were increased in patients with BCIM-SSc; (2) there was a relationship between TSP-1 serum levels and macrophage infiltration, fibrotic replacement, and reduction of the number of vessels in the muscle biopsy; and (3) TSP-1 was increased in muscle samples of patients with BCIM-SSc.

TSP-1 is a matricellular protein mainly released by activated platelets, but, in an inflammatory context and in response to stress, it is also produced by other cells such as fibroblasts, endothelial cells, and macrophages.28–30 TSP-1 is involved in numerous biological processes through its direct binding to CD36 and CD47 receptors or directly modulating the function of soluble molecules such as vascular endothelial growth factor or activating latent TGFβ to promote fibrotic expansion31 as described in skin-derived fibroblasts from patients with SSc.32 Our results are in line with these observations, in which TSP-1 and serum from patients with BCIM-SSc enhanced proliferation and production of components of the extracellular matrix in skeletal muscle–derived fibroblasts. In vivo, IM administration of TSP-1 resulted in a mild increase in fibrosis 2 weeks after treatment. TSP-1 has an important regulatory role in the proliferation of endothelial cells, and it is therefore important for the capillarization process of the skeletal muscle. Accordingly, TSP-1 and serum of patients with BCIM-SSc disrupted vascular networks in vitro. However, our in vivo results did not show significant differences in the number of capillaries between TSP-1 injected and vehicle. These discrepancies may be explained by the fact that short-term delivery of TSP-1 is not enough to induce any pathologic change due to TSP-1 itself. In fact, other authors have shown that chronic delivery of TSP-1 decreased muscle capillarity in mice.33 In addition, macrophages are a source of TSP-1 that influence their own phenotype toward a profibrotic state and, in turn, promote macrophage recruitment.34–36 Consequently, IM injection of TSP-1 in healthy mice resulted in infiltration of M2 macrophages with a profibrotic phenotype. The relation between inflammation in skeletal muscle and TSP-1 has been also described in other muscle diseases.37,38 We reported that that absence of dysferlin, a protein involved in sarcolemma repair, leads to an upregulation of TSP-1.38 Muscle biopsy of patients with dysferlinopathy is characterized by inflammatory infiltrates of macrophages and necrotic fibers with mild upregulation of major histocompatibility complex class. We do not know the origin of TSP-1 upregulation in our patients with BCIM-SSc, but similarly to dysferlinopathy, it may contribute to the inflammation observed. Moreover, TSP-1 may have an impact in the muscle regeneration process, as we observed that it induces a reduction in the number and size of myotubes in vitro, and we observed a reduction in the myofiber size in the muscle biopsies of patients with BCIM-SSc. This potential role of TSP-1 has not been previously described and needs further studies, but the fact that higher TSP-1 levels are associated to lower muscle mass and higher macrophagic infiltration in dystrophic mice may also support our findings.39 Considering all these evidences, we believe that TSP-1 has an important role in the expansion of fibrotic tissue and may also participate in loss of capillaries and consequently muscle fiber damage in patients with BCIM-SSc.

Therefore, drugs blocking TSP-1 could be a potential therapy in these patients.40 Although TSP-1 blockage demonstrated a reduction of fibrosis in animal models,40 nowadays there is no treatment designed to target TSP-1 in humans. Tumor necrosis factor (TNF) alpha upregulates the expression of TSP-1 in muscle cells,37 and therefore, it would be beneficial for these patients. However, reports on the effect of TNF-alpha inhibitors (infliximab, adalimumab, and etanercept) in inflammatory muscle diseases indicate that they are not effective and may be deleterious.20

In summary, we described the clinical and pathologic findings of a cohort of patients with BCIM associated with SSc. Our data suggest that TSP-1 has an important role in the development of the disease, promoting fibrotic expansion, capillary dysfunction leading to myofiber damage.

Acknowledgment

The authors thank the patients participating in this project for their patience with us.

Glossary

- ACR

American College of Rheumatology

- BCIM

brachio-cervical inflammatory myopathy

- DM

dermatomyositis

- EULAR

European League Against Rheumatism

- HLA

human leukocyte antigen

- IMNM

immune-mediated necrotizing myopathy

- SSc

systemic sclerosis

- TGFβ

transforming growth factor beta

- TNF

tumor necrosis factor

- TSP-1

thrombospondin-1

Appendix. Authors

Study funding

This work was supported by FIS (PI18/1525) to J. Díaz-Manera and X. Suárez-Calvet and by FIS (PI15/1597) to E. Gallardo (Fondo Europeo de Desarrollo Regional [FEDER], Instituto de Salud Carlos III, Spain). X. Suárez-Calvet was supported by Sara Borrell postdoctoral fellowship (CD18/00195), Fondo Social Europeo (FSE), Instituto de Salud Carlos III (Spain). Funders did not participate in the study design.

Disclosure

The authors report no disclosures. Go to Neurology.org/NN for full disclosures.

References

- 1.Pestronk A, Kos K, Lopate G, Al-Lozi MT. Brachio-cervical inflammatory myopathies: clinical, immune, and myopathologic features. Arthritis Rheum 2006;54:1687–1696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gao AF, Saleh PA, Kassardjian CD, Vinik O, Munoz DG. Brachio-cervical inflammatory myopathy with associated scleroderma phenotype and lupus serology. Neurol Neuroimmunol Neuroinflamm 2018;5:e410 doi: 10.1212/NXI.0000000000000410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Rojana-Udomsart A, Fabian V, Hollingsworth PN, Walters SE, Zilko PJ, Mastaglia FL. Paraspinal and scapular myopathy associated with scleroderma. J Clin Neuromuscul Dis 2010;11:213–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Denton CP, Khanna D. Systemic sclerosis. Lancet 2017;390:1685–1699. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.West SG, Killian PJ, Lawless OJ. Association of myositis and myocarditis in progressive systemic sclerosis. Arthritis Rheum 1981;24:662–668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Russell ML, Hanna WM. Ultrastructure of muscle microvasculature in progressive systemic sclerosis: relation to clinical weakness. J Rheumatol 1983;10:741–747. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Averbuch-Heller L, Steiner I, Abramsky O. Neurologic manifestations of progressive systemic sclerosis. Arch Neurol 1992;49:1292–1295. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hietaharju A, Jaaskelainen S, Kalimo H, Hietarinta M. Peripheral neuromuscular manifestations in systemic sclerosis (scleroderma). Muscle Nerve 1993;16:1204–1212. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Mimura Y, Ihn H, Jinnin M, Asano Y, Yamane K, Tamaki K. Clinical and laboratory features of scleroderma patients developing skeletal myopathy. Clin Rheumatol 2005;24:99–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Muangchan C, Canadian Scleroderma Research G, Baron M, Pope J. The 15% rule in scleroderma: the frequency of severe organ complications in systemic sclerosis: a systematic review. J Rheumatol 2013;40:1545–1556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Paik JJ, Wigley FM, Mejia AF, Hummers LK. Independent association of severity of muscle weakness with disability as measured by the health assessment questionnaire disability index in scleroderma. Arthritis Care Res (Hoboken) 2016;68:1695–1703. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garcin B, Lenglet T, Dubourg O, Mesnage V, Levy R. Dropped head syndrome as a presenting sign of scleromyositis. J Neurol Sci 2010;292:101–103. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Paik JJ. Myopathy in scleroderma and in other connective tissue diseases. Curr Opin Rheumatol 2016;28:631–635. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.van den Hoogen F, Khanna D, Fransen J, et al. 2013 classification criteria for systemic sclerosis: an American College of Rheumatology/European League against Rheumatism collaborative initiative. Arthritis Rheum 2013;65:2737–2747. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Martinez-Martinez L, Lleixa MC, Boera-Carnicero G, et al. Anti-NF155 chronic inflammatory demyelinating polyradiculoneuropathy strongly associates to HLA-DRB15. J Neuroinflammation 2017;14:224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pinol-Jurado P, Suarez-Calvet X, Fernandez-Simon E, et al. Nintedanib decreases muscle fibrosis and improves muscle function in a murine model of dystrophinopathy. Cell Death Dis 2018;9:776. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ladislau L, Suarez-Calvet X, Toquet S, et al. JAK inhibitor improves type I interferon induced damage: proof of concept in dermatomyositis. Brain 2018;141:1609–1621. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sasaki S, Iwata M. Motor neuron disease with predominantly upper extremity involvement: a clinicopathological study. Acta Neuropathol 1999;98:645–650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tawil R. Facioscapulohumeral muscular dystrophy. Handb Clin Neurol 2018;148:541–548. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Dalakas MC. Inflammatory muscle diseases. N Engl J Med 2015;372:1734–1747. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ranque B, Authier FJ, Le-Guern V, et al. A descriptive and prognostic study of systemic sclerosis-associated myopathies. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1474–1477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bhansing KJ, Lammens M, Knaapen HK, van Riel PL, van Engelen BG, Vonk MC. Scleroderma-polymyositis overlap syndrome versus idiopathic polymyositis and systemic sclerosis: a descriptive study on clinical features and myopathology. Arthritis Res Ther 2014;16:R111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diaz-Manera J, Llauger J, Gallardo E, Illa I. Muscle MRI in muscular dystrophies. Acta Myol 2015;34:95–108. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simeon CP, Fonollosa V, Tolosa C, et al. Association of HLA class II genes with systemic sclerosis in Spanish patients. J Rheumatol 2009;36:2733–2736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Stenzel W, Goebel HH, Aronica E. Review: immune-mediated necrotizing myopathies—a heterogeneous group of diseases with specific myopathological features. Neuropathol Appl Neurobiol 2012;38:632–646. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Reiss Y, Droste J, Heil M, et al. Angiopoietin-2 impairs revascularization after limb ischemia. Circ Res 2007;101:88–96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Li C, Hampson IN, Hampson L, Kumar P, Bernabeu C, Kumar S. CD105 antagonizes the inhibitory signaling of transforming growth factor beta1 on human vascular endothelial cells. FASEB J 2000;14:55–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.DiPietro LA, Polverini PJ. Angiogenic macrophages produce the angiogenic inhibitor thrombospondin 1. Am J Pathol 1993;143:678–684. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Dameron KM, Volpert OV, Tainsky MA, Bouck N. Control of angiogenesis in fibroblasts by p53 regulation of thrombospondin-1. Science 1994;265:1582–1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Phelan MW, Forman LW, Perrine SP, Faller DV. Hypoxia increases thrombospondin-1 transcript and protein in cultured endothelial cells. J Lab Clin Med 1998;132:519–529. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sweetwyne MT, Murphy-Ullrich JE. Thrombospondin1 in tissue repair and fibrosis: TGF-beta-dependent and independent mechanisms. Matrix Biol 2012;31:178–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mimura Y, Ihn H, Jinnin M, Asano Y, Yamane K, Tamaki K. Constitutive thrombospondin-1 overexpression contributes to autocrine transforming growth factor-beta signaling in cultured scleroderma fibroblasts. Am J Pathol 2005;166:1451–1463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Audet GN, Fulks D, Stricker JC, Olfert IM. Chronic delivery of a thrombospondin-1 mimetic decreases skeletal muscle capillarity in mice. PLoS One 2013;8:e55953. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mansfield PJ, Suchard SJ. Thrombospondin promotes chemotaxis and haptotaxis of human peripheral blood monocytes. J Immunol 1994;153:4219–4229. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Fordham JB, Hua J, Morwood SR, et al. Environmental conditioning in the control of macrophage thrombospondin-1 production. Sci Rep 2012;2:512. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Chen X, Yang B, Tian J, et al. Dental follicle stem cells ameliorate lipopolysaccharide-induced inflammation by secreting TGF-beta3 and TSP-1 to elicit macrophage M2 polarization. Cell Physiol Biochem 2018;51:2290–2308. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Salajegheh M, Raju R, Schmidt J, Dalakas MC. Upregulation of thrombospondin-1(TSP-1) and its binding partners, CD36 and CD47, in sporadic inclusion body myositis. J Neuroimmunol 2007;187:166–174. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.De Luna N, Gallardo E, Sonnet C, et al. Role of thrombospondin 1 in macrophage inflammation in dysferlin myopathy. J Neuropathol Exp Neurol 2010;69:643–653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Urao N, Mirza RE, Heydemann A, Garcia J, Koh TJ. Thrombospondin-1 levels correlate with macrophage activity and disease progression in dysferlin deficient mice. Neuromuscul Disord 2016;26:240–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Xie XS, Li FY, Liu HC, Deng Y, Li Z, Fan JM. LSKL, a peptide antagonist of thrombospondin-1, attenuates renal interstitial fibrosis in rats with unilateral ureteral obstruction. Arch Pharm Res 2010;33:275–284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data presented in this study are available on reasonable request.

Supplementary methods (e-methods, links.lww.com/NXI/A213) can be downloaded. Primary and secondary antibodies used in the study are listed in table e-1. mRNA specific probes used for qPCR studies are listed in table e-2.