Abstract

Malignant transformation of abdominal wall endometriosis lesions developed in a cesarean section scar is a rare event. Patients with uterine adenomyosis but without endometriosis can also develop abdominal wall malignant carcinoma after a gynecologic surgery. The treatment of abdominal wall clear cell adenocarcinoma combines tumor surgical excision with free margins, radiotherapy and chemotherapy. We report a case of clear cell carcinoma arising from an abdominal wall cesarean section scar in a patient without history of endometriosis.

Keywords: uterine adenomyosis, extra-pelvic endometriosis, adenomyosis malignant transformation, clear cell abdominal wall carcinoma, cesarean delivery scar endometriosis

INTRODUCTION

Pelvic endometriosis is a common disease affecting from 7 to 15% of women in reproductive age [1]. It is defined by the presence of aberrant endometrial glands and stroma outside the uterine cavity, and it can be found in intra- and extra-abdominal sites [1]. Abdominal wall endometriosis is a well-established entity, representing 1–2% of all endometriosis lesions, and it usually occurs after cesarean section [2]. Malignant degeneration of this lesion is very rare, and, in most cases reported in the literature, patients presented previous history of endometriosis.

To our knowledge, we report the first case of a clear cell carcinoma arising from an abdominal wall cesarean section scar in a patient without history of endometriosis, and in whom uterine adenomyosis was found in the surgical specimen.

CASE REPORT

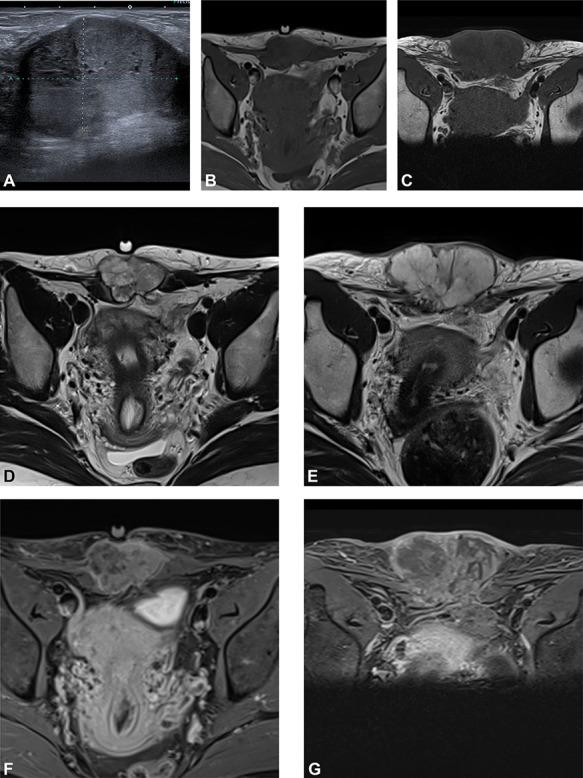

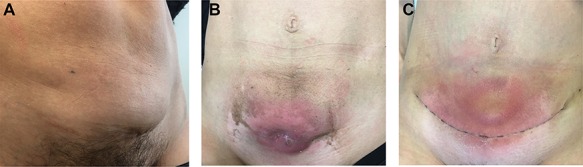

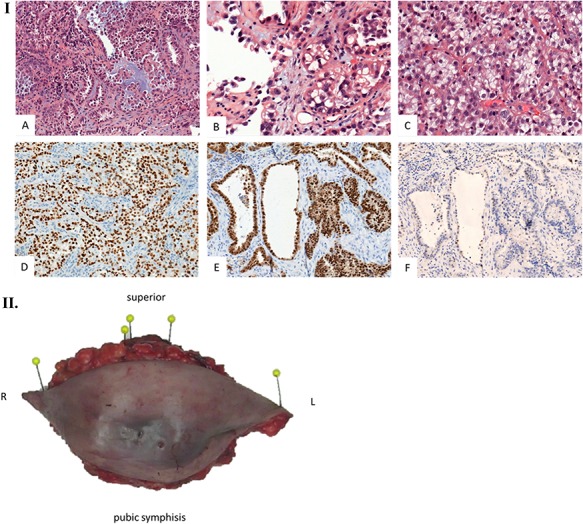

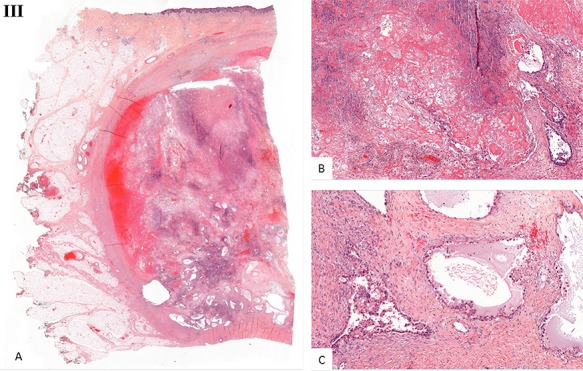

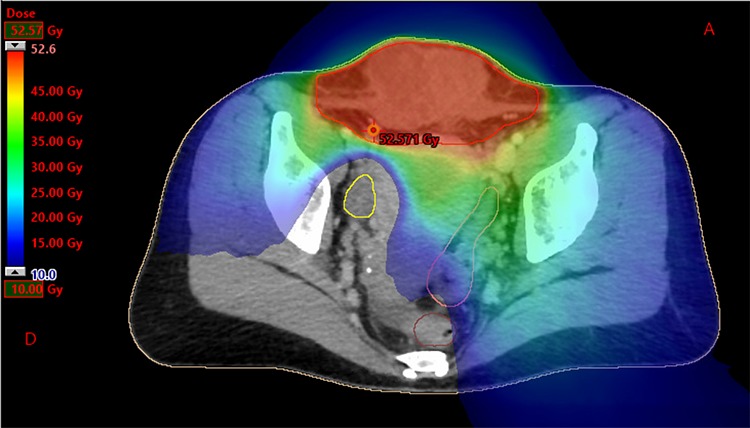

We present the case of a 44-year-old woman with no previous history of endometriosis, cancer or other relevant medical condition. She had two cesarean deliveries by a Pfannenstiel incision in 2004 and 2014. In May 2018, the patient presented a subcutaneous abdominal wall mass. The ultrasound described a 2-cm nodule compatible with an endometrioma developed on cesarean section scar. From January 2019, the patient reported a rapidly growing and painful mass, and the abdominal ultrasound confirmed a 45-mm well-defined mass showing acoustic enhancement with diffuse ground-glass echoes (Fig. 1A). The pelvic magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) confirmed an infiltrative heterogeneous lesion measuring 5 cm arising from the Pfannenstiel incision and partially involving rectus abdominis muscles (Fig. 1B,D,F). The MRI did not evidence other signs of pelvic or extra-pelvic endometriosis. The patient was referred to our comprehensive cancer center. Physical examination revealed an abdominal wall mass on the cesarean section scar, measuring around 6 cm (Fig. 2A). No abnormal findings were observed in pelvic examination. The ultrasound-guided biopsy revealed a clear cell carcinoma. Microscopic examination showed a malignant proliferation with glandular, nested and focal papillary patterns. Tumor cells had clear cytoplasm, with hyperchromatic nuclei and hobnail feature (Fig. 3I-A,B,C). They were strongly immunoreactive for CK7, PAX8 and HNF-1β (Fig. 3I-D,E). They were negative for calretinin, CK20, CK5/6, WT1, ER and PR. There was a wild-type pattern with anti-p53 antibody (weak and heterogeneous positivity) (Fig. 3I-F). A hysteroscopy and curettage showed a normal endometrium. Computed tomography of the chest, abdomen and pelvis did not evidence distant metastasis. After discussion at the tumor board, neoadjuvant radiation therapy before surgical excision was recommended due to rapid and extensive local progression. From March 2019 to May 2019, 50 Gy was delivered in 25 fractions to the abdominal wall tumor with helicoidal intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) using Tomotherapy® (Fig. 4). We tried to spare the right ovary from the irradiation fields, delivering a maximum dose of 5 Gy and a mean dose of 3.9 Gy. In June 2019, a wide surgical excision of the lesion (Fig. 3II) and abdominal wall reconstruction using a biological mesh, as well as total hysterectomy and bilateral salpingectomy, were performed. A careful inspection of abdominopelvic cavity was done during surgery, and no signs of endometriosis were found. Both ovaries were macroscopically normal.

Figure 1.

(A) Preoperative ultrasound: ultrasound exam at diagnosis showing a well-defined mass with acoustic enhancement and diffuse ground-glass echoes. (B) Magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) findings: before neoadjuvant radiotherapy (B, D, F) and at the end of the treatment (C, E, G). MRI exams show a well-defined solid mass which presents iso-signal on T1WI (B, C), hyper signal on T2WI (D, E) and heterogeneous enhancement after gadolinium injection (F, G). This mass partially involves both rectus abdominis muscles. A progression, mainly due to necrosis, with an increased size after radiotherapy can be observed.

Figure 2.

Physical examination. (A) Before neoadjuvant radiotherapy: parietal mass measuring 6 cm at diagnosis and arising from cesarean delivery scar. (B) At the end of radiotherapy: parietal mass measuring 5 cm; a cutaneous fistula and grade 2 radiation-induced epidermitis were observed at the end of the treatment. (C) Postoperative course: after surgery, the patient presented a parietal seroma just above the scar.

Figure 3.

Histological examination. (I) Microscopic examination of the biopsy: A. Glandular and focal papillar pattern , HE stain x200 B. Hobnail morphology of tumoral cells, HE stain x400 C. Nests of neoplastic clear cells, HE stain x400 D. Nuclear immunoreactivity with anti-PAX8 antibody, x200 E. Nuclear immunoreactivity with anti-HNF-1β antibody, x200 F. Wild type pattern with anti-p53 antibody, x200. (II) Surgical specimen. Resection of the parietal mass with free margins after radiotherapy. (III) Microscopic examination of resected specimen: A. Nodular lesion involving dermis and hypodermis, HE x5 B. Hemorrhage, fibrotic and necrotic changes, HE x50 C. Microcystic predominant pattern, HE x100.

Figure 4.

Dosimetry with helicoidal tomotherapy. We can observe the delivered doses from 10 to 52.6 Gy, sparing the right ovary.

Gross histopathological examination revealed a nodular lesion involving the dermis and hypodermis, measuring 7 × 5 cm, with necrotic, hemorrhagic and fibrotic changes. Microscopic examination of the resected specimen showed a similar histopathology to the biopsy (Fig. 3III).

The case field was discussed in the French rare ovarian malignancy network (TMRO—Tumeurs Malignes Rares de l’Ovaire), and adjuvant treatment with chemotherapy was proposed. However, the patient refused any kind of adjuvant treatment. After a follow-up of 5 months, she was disease-free.

DISCUSSION

Malignant transformation of endometriosis lesions is rare, occurring in 1% of cases [1]. A review of the literature reported that malignant abdominal wall endometriosis concerns mostly clear cell and endometrioid carcinomas [3]. Many cases of adenocarcinoma arising from endometriosis in an extrauterine site have been reported in the literature since it was firstly described in 1925. Criteria for the diagnosis of a malignancy arising from endometriosis in the ovary were then established: (i) it should be clear evidence of endometriosis near the tumor; (ii) no other primary carcinoma should be identified and (iii) the presence of tissue resembling endometrial stroma surrounding characteristic epithelial glands is needed [4]. In our case, just the second and the third criteria were fulfilled. Nevertheless, multiple foci of adenomyosis were found in the myometrium.

Adenomyosis is a relatively frequent disease of unknown etiology, which is usually difficult to diagnose. There are very few cases in the literature describing a malignant transformation of adenomyosis. Etiology and prevalence of this transformation are unknown, and, although very rarely encountered, endometrioid adenocarcinoma is the most frequent histologic subtype arising from adenomyosis [5]. To our knowledge, there are very few cases in the literature reporting clear cell carcinoma arising from adenomyosis, and in all cases it was an intrauterine transformation without extra-pelvic disease [6]. In our case, we can hypothesize that clear cell carcinoma could have arisen from an iatrogenic transplantation of adenomyosis during cesarean delivery, with a posterior malignant transformation.

The rarity of occurrence of this type of malignancy makes it difficult to generalize outcomes or to standardize treatment protocols. Lai et al. [7] reported their 15-year experience in the clinical management of patients with clear cell carcinoma of the abdominal wall. They proposed a primary surgical treatment with complete and wide excision, and free margins of the abdominal wall tumor and all intra-abdominal lesions evidenced on preoperative imaging, hysterectomy and bilateral inguinal lymph node dissection. [8] Complementary radiotherapy can be used when the disease is confined to the pelvis, and it may be combined with progestin therapy. In this case, the patient presented a rapid local invasion and tumoral board proposed a neoadjuvant radiation therapy in order to stabilize tumoral size and, therefore, to improve the quality of the resection, extrapolating the strategy from sarcoma’s management. The value of adjuvant platinum-based chemotherapy in preventing relapse is unknown; however, it is offered in most cases to prevent tumor recurrences.

In conclusion, we report the first case of extrauterine adenomyosis malignant transformation in a cesarean section scar in a patient without endometriosis. The etiopathology of this malignancy might be similar to the malignant transformation of endometriosis lesions in an abdominal wall scar, but to date this is only a hypothesis.

AUTHORS’ CONTRIBUTION

Anaïs Provendier: Conceptualization, data curation, methodology, writing—original draft. Martina Aida Angeles: Conceptualization, data curation, methodology, writing—original draft. Olivier Meyrignac: Conceptualization, data curation, methodology, imaging processing, writing—original draft. Claire Illac: Conceptualization, data curation, methodology, imaging processing, writing—original draft. Anne Ducassou: Conceptualization, data curation, methodology, writing—original draft. Carlos Martínez-Gómez: Conceptualization, data curation, methodology, writing—original draft. Laurence Gladieff: Conceptualization, project administration, methodology writing—review. Alejandra Martinez: Conceptualization, project administration, methodology writing—review. Gwénaël Ferron: Conceptualization, project administration, methodology writing—review.

PATIENT CONSENT

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the editor-in-chief of this journal on request.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

FUNDING

Martina Aida Angeles acknowledges the grant support from ‘la Caixa’ Foundation, Barcelona (Spain).

References

- 1. Varma R, Rollason T, Gupta JK, Maher ER. Endometriosis and the neoplastic process. Reproduction 2004;127:293–304 10.1530/rep.1.00020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Sergent F, Baron M, Le Cornec J, Scotté M, Mace P, Marpeau L. Malignant transformation of abdominal wall endometriosis: a new case report. J Gynecol Obs Biol Reprod 2006;35:186–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Heaps JM, Nieberg RK, Berek JS. Malignant neoplasms arising in endometriosis. Obstet Gynecol 1990;75:1023–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Sampson JA. Endometrial carcinoma of the ovary, arising in endometrial tissue in that organ. Arch Surg 1925;10:1–72. [Google Scholar]

- 5. Koshiyama M, Suzuki A, Ozawa M, Fujita K, Sakakibara A, Kawamura M, et al. . Adenocarcinomas arising from uterine adenomyosis: a report of four cases. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2002;21:239–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hirabayashi K, Yasuda M, Kajiwara H, Nakamura N, Sato S. Clear cell adenocarcinoma arising from adenomyosis. Int J Gynecol Pathol 2009;28:262–6 10.1097/PGP.0b013e31818e101f. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Lai YL, Hsu HC, Kuo KT, Chen YL, Chen CA, Cheng WF. Clear cell carcinoma of the abdominal wall as a rare complication of general obstetric and gynecologic surgeries: 15 years of experience at a large academic institution. Int J Environ Res Public Health 2019;16:pii: E552. 10.3390/ijerph16040552. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Hong SC, Khoo CK. An update on adenomyosis uteri. Gynecol Minim Invasive Ther 2016;5:106–8 10.1016/j.gmit.2015.08.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]