Abstract

The prevalence of thyroid cancer, especially in women, is increasing dramatically. Therefore, patients often undergo thyroidectomy upon diagnosis. However, the cosmetic outcome after surgery is of particular concern for many patients. Thus, minimally invasive procedures for treating thyroid disease have been established in recent decades. Total endoscopic and robotic procedures have been slowly and successively introduced while meeting all oncological criteria. Our analysis of the advantages and disadvantages of scarless surgical procedures suggests that the cosmetic aspects of these surgeries will continue to become more important. This review assesses the recent findings regarding the roles of endoscopic and robotic procedures in thyroid cancer surgery.

Keywords: Scarless surgery, minimally invasive, robotic, thyroid cancer, gland surgery, endoscopic surgery

Introduction

Good health and an attractive appearance throughout life are valuable to many people in the 21st century.1 Most individuals believe that an attractive appearance is an external measure of their health. These individuals emphasize that a perfect appearance is evidence of a good health status and that a healthy human body should therefore contain no scars. Although scars can often be covered, this is sometimes problematic in the head and neck area. Some individuals consider that having a scar on the neck is unacceptable.

During the past several decades, the occurrence of thyroid cancer (TC) has increased dramatically, and it is now the fastest growing cancer in women,2–4 especially young women.5 However, the incidence of TC is also increasing in men.6

In this review, we discuss the current knowledge regarding surgical interventions for TC, including scarless surgery, and address the oncological aspects and future perspectives of endoscopic and robotic procedures in the surgical treatment of TC. We decided to perform a mini-review because of the amount of literature available regarding the changes in thyroid surgery procedures. Minimally invasive procedures for the management of TC are rather new and still debatable, resulting in limited numbers of articles on this topic.

Literature review and search strategy

PubMed, Medline, and the Cochrane Library were searched for relevant literature up to 28 February 2019. The key words used for the search strategy were “human,” “thyroidectomy,” “scarless surgery,” “endoscopic surgery,” “robotic surgery,” “TOETVA,” and “TORT.” The outcomes of interest were patient characteristics, adverse events and complications, the recurrence rate, and surgical completeness. The quality of the included studies was evaluated using the Newcastle–Ottawa scale.

Primary objectives

The primary objective was to determine whether endoscopic thyroidectomy (ET) and robotic thyroidectomy (RT) are safe and feasible in patients with TC. We also assessed which type of TC is most suitable for scarless surgery and which technique is the most highly recommended (endoscopic, transoral, or robotic).

Selection strategy

This review included studies that analyzed patients with TC who underwent open thyroidectomy (OT), total ET, or RT. The articles comprised case series, case control studies, meta-analyses, randomized controlled studies, and observational studies. The full article of each qualifying study was obtained.

Results

The initial search yielded 1,348 potentially relevant articles. Of these, 1,327 studies were excluded for the following reasons: non-English language, duplicates, mini-reviews, case reports, clinical images, letters to the editor, editorials, expert opinions, conference materials, and others. Twenty-one full-text articles were assessed for eligibility, but after further exclusion of some articles (case series of patients who had TC with secondary tumors and studies with overlapping patient cohorts), 17 articles were finally included in this mini-review.

Which type of TC is most suitable for scarless surgery?

Some authors have indicated that among all malignant thyroid tumors, the occurrence of well-differentiated TC characterized by a low risk of aggressiveness is showing the greatest increase.7 Mo et al.8 reported that because of easier access to thyroid ultrasound with subsequent fine-needle aspiration biopsy of newly discovered thyroid lesions, the detection rate of papillary TC (PTC) is increasing. In particular, the incidence of small PTC (largest dimension of ≤1.0 cm), also known as papillary thyroid microcarcinoma (PTMC), is predominantly increasing.9 Its predicted incidence rate for 2019 reached 26.9/100,000 per year in some populations.8 However, the clinical characteristics of PTC, such as its slow growth and excellent prognosis, make it suitable for remote-access endoscopic surgery. Additionally, such an approach is often in high demand by many patients because of the lack of a noticeable neck scar.7 Some authors have emphasized that female patients have played a main role in the rapid emergence and acceptance of ET.10 Additionally, Malandrino et al.11 noticed that unilateral PTMC, which is the most suitable tumor for endoscopic approaches, occurs more frequently in young women.

From OT to ET

For some patients, high oncological safety and good cosmetic outcomes must be simultaneously achieved. Surgical procedures have been changing to meet these patients’ demands. Minimally invasive procedures were established in 1997, when Hüscher et al.12 first performed total ET. Other approaches were introduced thereafter.13–15 In 2009, the first reports of RT were presented.16,17 Since then, better clinical outcomes for RT than OT have been reported. The most important outcomes, especially for women, were better cosmetic results, shorter recovery periods, reduced neck pain and discomfort in swallowing, and a generally better quality of life after thyroidectomy.18–20 Other advantages of RT reported by many authors are improved access to a narrow space, magnified three-dimensional imaging, reduced effects of the surgeon’s tremor, improved ergonomics, a smaller “assistance factor,” and a superior range of motion.20–22 In some patients, even minimal incisions might be unacceptable, especially on exposed parts of the body. Therefore, neck and anterior chest wall approaches are commonly excluded because they result in a visible scar in a natural position.8 Although not scarless, other available procedures include the endoscopic bilateral axillo-breast approach (EBABA), anterior chest wall approach, modified axillo-breast approach, and mixed approaches.23–26 However, some authors have indicated that in some cases, even a small incision in the breast is unacceptable.27,28

From ET and RT to natural orifice transluminal surgery

Natural orifice transluminal endoscopic surgery (NOTES) was developed with the aim of avoiding even small skin incisions. At present, the most common NOTES procedure involves the use of transvaginal access. The acceptance of NOTES by women is high.29 The basic NOTES procedure for treatment of TC is transoral ET (TOET). 30 The surgeon may use the floor of the mouth for primary access or a completely vestibular approach; i.e., the TOET vestibular approach (TOETVA).5 Additionally, TOET seems to be the only procedure that can be called a “true scarless surgery.” The degree of cosmetic satisfaction after these procedures in many patients is high, but it might differ slightly according to the approach.31

Transoral, endoscopic, or robotic procedure?

Some authors have emphasized that EBABA, as an outside neck approach, is an alternative for select patients who are very concerned about scarless procedures and who are not qualified to undergo treatment with a transoral technique.31 Other authors have stated that EBABA is the most suitable approach for patients with larger thyroid tumors, toxic goiters, or low-grade TC.32 The currently recommended size of thyroid tumors that can be treated by scarless ET is 4 to 6 cm.10 However, some other authors have expressed doubts about the effectiveness, efficiency, and oncological safety of ET.33 In their opinion, all endoscopic techniques used in the treatment of TC should be critically evaluated. Others have clearly emphasized that ET has some limitations.34 In their opinion, ET restricts the motion of surgical instruments and provides a two-dimensional camera view. This is why RT has some advantages over ET. For example, the da Vinci Robotic System offers a highly magnified three-dimensional view, fine motor scaling, a tremor-free operation, and improved endo-wrist function.16,17,34

Thus, several studies have demonstrated the superiority of scarless procedures over open surgery.3,5,7,8,17,29–32,34,35 However, the most certain advantage is the lack of a neck scar; the other clinical outcomes remain debatable. For example, the oncological safety of EBABA or TOETVA for patients with PTC is still unknown, and there is no worldwide consensus on this type of surgery for the treatment of this malignancy.

Discussion

Despite many authors’ vast experience in performing robotic and endoscopic procedures, the role of total ET and RT in treating thyroid tumors remains controversial.3 Additionally, benign thyroid tumors and malignant lesions such as PTC have been treated using endoscopic and robotic techniques with ultimate success.17 Among all thyroid malignancies, only PTC seems to be the most suitable malignant tumor for treatment via endoscopic and robotic techniques. This type of TC has an excellent prognosis, and surgical treatment remains its primary and basic therapeutic method.

The choice for or against RT

With the popularity of endoscopic and robotic approaches because these procedures leave no neck scar, which is unfortunately present after classic procedures, modern technologies have been considered attractive alternatives to OT. When the da Vinci System was introduced for the first time in 2009, many potential advantages of RT were recognized.16,17 With this development, it became almost certain that this surgical direction would be quickly developed. Because of the many positive aspects of robotic approaches, such as the good cosmetic results and improved ergonomics, the da Vinci technique has been widely used.19 However, some opponents to the introduction of new techniques35,36 have highlighted the low morbidity rate and excellent results of OT as well as the longer operative time and higher cost of RT.

Is PTC the most suitable type of TC for ET and RT?

Because small PTCs, such as PTMCs, are treated by many surgeons via both endoscopic and robotic approaches,3,7,8,19,24,27,28 many patients with larger tumors (>1.0 cm) undergo treatment with scarless surgical procedures.16,17,19,34 Although OT is still one of the most common surgical procedures for treatment of thyroid gland pathologies, other techniques, such as ET and RT, have been gaining ground. Some authors have stated that the main reason for this might be that a cutaneous incision in the neck is required when performing conventional OT.3 For many patients, this scar is more important than the fact that OT is still a standard surgery for PTC with low morbidity and minimal mortality rates.3 However, endoscopic and robotic techniques have clearly allowed the simultaneous acquisition of good cosmetic effects and effective surgical resection. Aside from the longer time required by these procedures than by conventional thyroidectomy, the degree of cosmetic satisfaction is very high.31

Oncological effectiveness is one of the most important concerns in the treatment of all malignant tumors; the same applies to thyroid tumors. Although PTC has low aggressiveness and an excellent prognosis, high accuracy of lymphadenectomy, if required, is also critical. Chen et al.3 found no significant differences among ET, RT, and OT. Therefore, current evidence indicates that the level of completeness of oncological procedures using “modern methods” is high.

Postsurgical complications

Two of the most common and severe postsurgical complications of thyroid resection are recurrent laryngeal nerve paresis and hypocalcemia caused by hypoparathyroidism. Patients with unilateral recurrent laryngeal nerve palsy may not have serious respiratory difficulties; however, some problems with voice quality and hoarseness might be observed.37 Some previous studies showed no significant differences in the complication rates and postsurgical calcium levels between OT and “modern” techniques.38,39 Surgeons’ experience using RT and ET has become sufficient to produce a low complication rate and very high oncological efficacy rate. Some authors have added that using the da Vinci System in the treatment of PTC decreases the rate of complications without reducing oncological efficacy.40 It has also been reported that the outcomes of RT may be similar to those of OT, possibly even with better preservation of the parathyroid blood supply.40 With respect to postsurgical complications among the analyzed techniques, Lee et al.41 noted some benefits of RT. In their opinion, the 15-fold magnification in RT may increase the visibility of very small vessels, thus protecting the blood supply of the parathyroid glands. Additionally, monopolar hooks are no longer used, having been replaced by hot shears. Some authors have emphasized that this delicate instrument allows for more precise dissection.40 Moreover, in RT, the surgeon may control the traction force, while in OT, the surgeon does not have an absolute influence on assistance. According to some authors’ opinion, inadequate surgical manipulation of the recurrent laryngeal nerve, such as a too-high traction force, is the most common cause of injury to this nerve.42 These authors also emphasized that inappropriate actions by assistant surgeons during OT can be completely avoided in RT.42

Which patients choose scarless procedures?

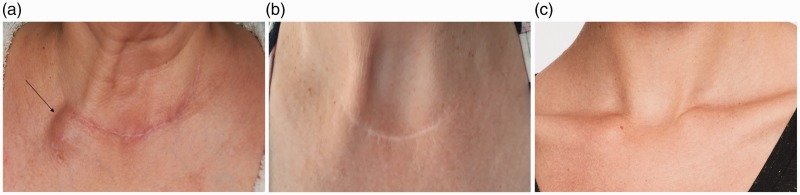

With respect to the demographic features of patients who undergo different types of surgery, RT and ET are mainly chosen by younger women, who may be more concerned with the cosmetic results.3,5,13,14 Our comparison of the demographic characteristics of patients who undergo thyroidectomy by different methods yielded very interesting results (Figure 1). We present the patients who underwent thyroidectomy due to PTMC. The patients (a) and (b) (Figure 1a,b) by the “conventional” approach and patient (c) (Figure 1c) by the TETVA. The cosmetic outcomes are obvious. Patients who undergo RT are younger, lower body mass index, undergo a higher proportion of hemithyroidectomy than total thyroidectomy, and have a lower stage of TC according to the eighth edition of the UICC/AJCC guidelines for PTC.42 In some authors’ opinion, the main cause of these differences is the greater desire to avoid a visible anterior neck scar in younger patients, especially younger women with smaller tumors without clinically evident lymph node metastases.34 However, the same authors confirm that the patients’ preferences and the rather strict indications for RT may cause selection bias. Randomized studies are strictly limited by financial issues. In almost all analyses, RT required a significantly longer time. According to many authors, the strongest contributing factors were the process of creating the flap and docking the robotic device,43–45 but others have added that the accumulation of experience and the learning curve also play roles.46

Figure 1.

Photographs of three women who underwent thyroidectomy due to papillary thyroid microcarcinoma (a) 12 and (b) 8 years previously by the “conventional” approach and (c) 2 years previously by the transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy vestibular approach. Eight years after the primary surgery in patient (a), thyroid cancer skin metastasis was identified (arrow). The cosmetic outcomes are obvious and can be compared in this figure, but the long-term oncological outcomes cannot yet be evaluated.

Conclusions

After analyzing all of the advantages and disadvantages of scarless surgical procedures, we assume that the cosmetic aspects of these procedures will become more important in future, including in surgery for TC. It seems that the achievement of “true” scarless procedures for select patients is the most likely direction of TC treatment.

Declaration of conflicting interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest.

Ethics statement

All research was carried out in compliance with the Helsinki Declaration.

Funding

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

ORCID iD

Krzysztof Kaliszewski https://orcid.org/0000-0002-3291-5294

References

- 1.Gordon RA, Crosnoe R, Wang X. Physical attractiveness and the accumulation of social and human capital in adolescence and young adulthood: assets and distractions. Monogr Soc Res Child Dev 2013; 78: 1–137. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wiltshire JJ, Drake TM, Uttley L, et al. Systematic review of trends in the incidence rates of thyroid cancer. Thyroid 2016; 11: 1541–1552. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Chen C, Huang S, Huang A, et al. Total endoscopic thyroidectomy versus conventional open thyroidectomy in thyroid cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ther Clin Risk Manag 2018; 14: 2349–2361. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim H, Devesa SS, Sosa JA, et al. Trends in thyroid cancer incidence and mortality in the United States, 1974-2013. JAMA 2017; 317: 1338–1348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Camenzuli C, Schembri Wismayer P, Calleja Agius J. Transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy: a systematic review of the practice so far. JSLS 2018; 22: pii: e2018.00026. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Liu C, Chen T, Zeng W, et al. Reevaluating the prognostic significance of male gender for papillary thyroid carcinoma and microcarcinoma: a SEER database analysis. Sci Rep 2017; 7: 11412. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jongekkasit I, Jitpratoom P, Sasanakietkul T, et al. Transoral endoscopic thyroidectomy for thyroid cancer. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am 2019; 48: 165–180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mo K, Zhao M, Wang K, et al. Comparison of endoscopic thyroidectomy via a modified axillo-breast approach with the conventional breast approach for treatment of unilateral papillary thyroid microcarcinoma. Medicine (Baltimore) 2018; 97: e13030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hedinger C, Williams ED, Sobin LH. The WHO histological classification of thyroid tumors: a commentary on the second edition. Cancer 1989; 63: 908–911. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Johri G, Chand G, Gupta N, et al. Feasibility of endoscopic thyroidectomy via axilla and breast approaches for larger goiters: widening the horizons. J Thyroid Res 2018; 2018: 4057542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Malandrino P, Pellegriti G, Attard M, et al. Papillary thyroid microcarcinomas: a comparative study of the characteristics and risk factors at presentation in two cancer registries. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013; 98: 1427–1434. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hüscher CS, Chiodini S, Napolitano C, et al. Endoscopic right thyroid lobectomy. Surg Endosc 1997; 11: 877. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ohgami M, Ishii S, Arisawa Y, et al. Scarless endoscopic thyroidectomy: breast approach for better cosmesis. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2000; 10: 1–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang JK, Ma L, Song WH, et al. Quality of life and cosmetic result of single-port access endoscopic thyroidectomy via axillary approach in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma. Onco Targets Ther 2016; 9: 4053–4059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shimazu K, Shiba E, Tamaki Y, et al. Endoscopic thyroid surgery through the axillo-bilateral-breast approach. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2003; 13: 196–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee KE, Rao J, Youn YK. Endoscopic thyroidectomy with the da Vinci robot system using the bilateral axillary breast approach (BABA) technique: our initial experience. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2009; 19: e71–e75. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kang SW, Jeong JJ, Yun JS, et al. Robot-assisted endoscopic surgery for thyroid cancer: experience with the first 100 patients. Surg Endosc 2009; 23: 2399–2406. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bae DS, Woo JW, Paek SH, et al. Antiadhesive effect and safety of sodium hyaluronate-carboxymethyl cellulose membrane in thyroid surgery. J Korean Surg Soc 2013; 85: 199–204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lee J, Kwon IS, Bae EH, et al. Comparative analysis of oncological outcomes and quality of life after robotic versus conventional open thyroidectomy with modified radical neck dissection in patients with papillary thyroid carcinoma and lateral neck node metastases. J Clin Endocrinol Metab 2013; 98: 2701–2708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Patel D, Kebebew E. Pros and cons of robotic transaxillary thyroidectomy. Thyroid 2012; 22: 984–985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kuppersmith RB, Salem A, Holsinger FC. Advanced approaches for thyroid surgery. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2009; 141: 340–342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lee J, Kang SW, Jung JJ, et al. Multicenter study of robotic thyroidectomy: short-term postoperative outcomes and surgeon ergonomic considerations. Ann Surg Oncol 2011; 18: 2538–2547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hakim Darail NA, Lee SH, Kang S, et al. Gasless transaxillary endoscopic thyroidectomy: a decade on. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2014; 24: e211-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Gao W, Liu L, Ye G, et al. Bilateral areolar approach endoscopic thyroidectomy for low-risk papillary thyroid carcinoma: a review of 137 cases [published correction in Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech. 2015; 25: 373]. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2015; 25: 19–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Woo J, Kim SK, Park I, et al. A novel robotic surgical technique for thyroid surgery: bilateral axillary approach (BAA). Surg Endosc 2017; 31: 667–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Chang EHE, Kim HY, Koh YW, et al. Overview of robotic thyroidectomy. Gland Surg 2017; 6: 218–228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan Z, Gu JL, Han QB, et al. Comparison of conventional open thyroidectomy and endoscopic thyroidectomy via breast approach for papillary thyroid carcinoma. Int J Endocrinol 2015; 2015: 239610–239614. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ren XT, Dai Z, Sha HC, et al. Comparative study of endoscopic thyroidectomy via a breast approach versus conventional open thyroidectomy in papillary thyroid microcarcinoma patients. Biomed Res 2017; 28: 5315–5320. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lamm SH, Zerz A, Steinemann DC. Scarless surgery: a vision becoming reality? Praxis (Bern 1994) 2016; 105: 453–456. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Yang J, Wang C, Li J, et al. Complete endoscopic thyroidectomy via oral vestibular approach versus areola approach for treatment of thyroid diseases. J Laparoendosc Adv Surg Tech A 2015; 25: 470–476. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Mercader Cidoncha E, Amunategui Prats I, Escat Cortés JL, et al. Scarless neck thyroidectomy using bilateral axillo-breast approach: initial impressions after introduction in a specialized unit and a review of the literature. Cir Esp 2019; 97: 81–88. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Chand G, Johri G. Extracervical endoscopic thyroid surgery via bilateral axillo-breast approach (BABA). J Minim Access Surg 2019. doi: 10.4103/jmas.JMAS_260_18. [Epub ahead of print]. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Terris DJ. Surgical approaches to the thyroid gland: which is the best for you and your patient? JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2013; 139: 515–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Cho JN, Park WS, Min SY, et al. Surgical outcomes of robotic thyroidectomy vs. conventional open thyroidectomy for papillary thyroid carcinoma. World J Surg Oncol 2016; 14: 181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sun GH, Peress L, Pynnonen MA. Systematic review and metaanalysis of robotic vs conventional thyroidectomy approaches for thyroid disease. Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg 2014; 150: 520–532. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Jackson NR, Yao L, Tufano RP, et al. Safety of robotic thyroidectomy approaches: meta-analysis and systematic review. Head Neck 2014; 36: 137–143. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Wojtczak B, Sutkowski K, Kaliszewski K, et al. Voice quality preservation in thyroid surgery with neuromonitoring. Endocrine 2018; 61: 232–239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Seup Kim B, Kang KH, Park SJ. Robotic modified radical neck dissection by bilateral axillary breast approach for papillary thyroid carcinoma with lateral neck metastasis. Head Neck 2015; 37: 37–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kang SW, Park JH, Jeong JS, et al. Prospects of robotic thyroidectomy using a gasless, transaxillary approach for the management of thyroid carcinoma. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2011; 21: 223–229. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paek SH, Kang KH, Park SJ. A comparison of robotic versus open thyroidectomy for papillary thyroid cancer. Surg Laparosc Endosc Percutan Tech 2018; 28: 170–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lee KE, Kim E, Koo do H, et al. Robotic thyroidectomy by bilateral axillo-breast approach: review of 1,026 cases and surgical completeness. Surg Endosc 2013; 27: 2955–2962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Amin MB, Edge S, Greene F, et al. AJCC cancer staging manual. 8th ed New York, NY: Springer, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 43.Kwak HY, Kim HY, Lee HY, et al. Robotic thyroidectomy using bilateral axillo-breast approach: comparison of surgical results with open conventional thyroidectomy. J Surg Oncol 2015; 111: 141–145. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Son SK, Kim JH, Bae JS, et al. Surgical safety and oncologic effectiveness in robotic versus conventional open thyroidectomy in thyroid cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Ann Surg Oncol 2015; 22: 3022–3032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Lee SG, Lee J, Kim MJ, et al. Long-term oncologic outcome of robotic versus open total thyroidectomy in PTC: a case-matched retrospective study. Surg Endosc 2016. 30: 3474–3479. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Kim WW, Jung JH, Park HY. A single surgeon’s experience and surgical outcomes of 300 robotic thyroid surgeries using a bilateral axillo-breast approach. J Surg Oncol 2015; 111: 135–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]