A new Director-General of WHO will be selected in May, 2017. Richard Horton and Udani Samarasekera asked the six candidates competing for the position about their candidacy.

The forthcoming election of the next Director-General of WHO comes at a critical moment not only for the world's only multilateral health agency but also for the precarious trajectory of global health itself. WHO is often criticised for failing to live up to the expectations of the health community. Sometimes, as in the case of how the agency managed the early stages of the Ebola virus outbreak, that criticism is justified. But WHO plays a vital and successful, and frequently neglected, part in setting norms and standards for health in countries. It has a powerful convening role. And, should a Director-General choose to do so, the agency has unprecedented authority to offer leadership in health.

As the world enters a new era—that of the Sustainable Development Goals—the Director-General has an essential voice in shaping the meaning of health in an era of human dislocation, pervasive inequality, mass migration, ecological degradation, climate change, war, and humanitarian crisis. Six excellent candidates for Director-General are standing. All have wide experience in health, as one would expect, but each offers a very different platform. Some candidates have formidable international experience in global health. Others have forged their reputations nationally. Some have strong technical credentials. Others offer political skills. Some come from countries that should be WHO's greatest concern. Others are from nations that are traditionally seen as donors. Some have expertise in what might be considered the traditional agenda of global health (infectious diseases and women's and children's health). Others bring experience of newer concerns. This great diversity of candidates is a strength. It allows the Executive Board of WHO in January, 2017, and then the World Health Assembly in May, to select a candidate based on a clear diagnosis of the global predicament for health and the solutions needed. To help clarify their experience, visions, and ideas, we invited each candidate to offer a brief manifesto and to answer a series of ten questions to illuminate their positions on what we see as some priorities for the organisation.

Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus

Ethiopia

© 2016 Photo courtesy of Dr. Tedros Adhanom

WHO has helped improve the health of people across the globe. More children live to celebrate their fifth birthdays, more women survive childbirth and have access to family planning, and significant progress has been made against infectious diseases.

Yet despite progress, daunting challenges lie ahead. Globalisation has made it easier for infectious pathogens to spark global pandemics that threaten lives and economic security. Antimicrobial resistance is rendering previously treatable diseases deadly. Ageing and unhealthy lifestyles are leading to non-communicable diseases, while injuries and health impacts of climate and environment change present a danger. Mass population movements also lead to global health challenges.

I envision a world in which everyone can lead healthy and productive lives, regardless of who they are or where they live. Achieving this vision and the Sustainable Development Goals requires a strong, revitalised WHO that is effectively managed, adequately resourced, results driven, and led with political acumen. We need a WHO that belongs to all of us equally, puts people first, and ensures health is at the centre of sustainable development efforts.

As Director-General of WHO, I would focus on five priorities:

-

(1)

Transforming WHO into a more effective, transparent, and accountable agency that is independent, science and innovation based, responsive and harmonised, with a shared vision at the headquarters, regional, and country levels. WHO has to strike a balance between bold reform and organisational stability to deliver results;

-

(2)

Advancing universal health coverage and ensuring all people can access the services they need without risk of impoverishment. This includes driving domestic resources for health, strengthening primary health care, and continuing to expand access to preventive services, diagnostics, and high-quality medicines for diseases like HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, diabetes, heart and chronic respiratory diseases, cancer, and mental health conditions;

-

(3)

Strengthening the capacity of national authorities and local communities to detect, prevent, and manage health emergencies, including antimicrobial resistance, and promote global health security;

-

(4)

Putting the wellbeing of women, children, and adolescents at the centre of the global health and development agenda and positioning health on the gender equality agenda;

-

(5)

Supporting national health authorities to better understand and address the health effects of climate and environmental change.

As Ethiopia's former Minister of Health and through my leadership at various global health initiatives, I have learned what it takes to create real and sustainable change. I led the revitalisation of weak health systems at Ethiopia's national and community levels; mobilised unprecedented human and financial resources; and catalysed large-scale responses to health emergencies. As Minister of Foreign Affairs, I have gained experience and skills in high-level political engagement, including with Heads of State, and played key roles in resolving conflicts and advancing regional integration. Last year, I helped find common ground between parties with polarised positions to forge the Addis Ababa Action Agenda for financing sustainable development.

My vision for WHO and for global health is ambitious, but achievable—and I am confident that I have the political and public health leadership skills, experience, and determination to deliver results.

(1) What would be your priorities as Director-General of WHO?

Tackling the biggest health challenges of the 21st century will require innovative solutions that defy “business as usual.” WHO will need to broaden and intensify its engagement with a wider range of stakeholders across the public, private, and civil society sectors. The agency should attract and retain global talent to make it more diverse and inclusive—and to ensure it has the expertise to lead from the front and the centre.

WHO must work with governments to build their national capacity for universal health coverage. Strong, resilient health systems—including infrastructure, workforce, and information systems—are essential to driving good health for all. It is through these systems that children are vaccinated, pregnant women receive antenatal care, and patients with HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, and other communicable diseases receive their treatments. It is also through these systems that diseases like heart and chronic respiratory diseases, diabetes, cancer, and mental health conditions can be prevented, detected early, and managed. WHO must also place women, children, and adolescents—alongside other vulnerable populations—at the centre of its work.

Finally, we must strengthen WHO's response to emerging threats, including disease outbreaks like Ebola, Middle East respiratory syndrome, and Zika, as well as the health effects of climate and environmental change. WHO must work to harmonise emergency responses across partners while bolstering front-line defences at the national and local levels.

(2) WHO cannot do everything. What should WHO not do?

WHO should not consider other global health players as competitors and should not do what others can do better. There are many players working to improve public health globally across government, private sector, civil society, and academia—what I like to call the extended WHO family. The health issues of today—such as non-communicable diseases, antimicrobial resistance, and health security—must be addressed across all sectors, not just the health sector. All partners have a role to play. For its part, WHO should act as a leader and a convener, directing collective efforts toward shared goals, ensuring that everyone is playing to their strengths, and preventing duplication of efforts.

(3) What are the three biggest threats to the health of peoples across the world?

In my opinion, the biggest immediate threat to health is inequitable access to basic health coverage around the world. An estimated 400 million people, many of them women and children, lack access to essential health services. Without ensuring this critical, basic level of coverage—including a strong health workforce and access to medicines—we cannot have a healthy and prosperous world.

Secondly, antimicrobial resistance and health emergencies, including infectious disease outbreaks, pose unprecedented threats. The Ebola crisis in west Africa showed us the dangers of being unprepared for such emergencies, and the Zika outbreak further highlights the need to invest in basic research on the human and environmental health nexus, better surveillance, and new vector control tools. Further, as the microbes that cause diseases like tuberculosis, malaria, syphilis, and gonorrhoea become increasingly resistant to current treatments, we move closer to a world in which we are no longer able to effectively treat everyday infections—threatening to set back a century of progress.

Thirdly, health impacts of climate and environmental change pose a long-term threat, including potential rises in communicable, non-communicable, and vector-borne diseases. Climate change and variations also impact many aspects of life that are inextricably linked to health, including food security, economic livelihoods, air safety, and water and sanitation systems.

(4) What would you do to tackle those threats?

Through inclusive, engaging, and decisive leadership of WHO, I plan to address these threats by:

-

(1)

Helping countries expand their health coverage and protect hard-won gains—particularly as they tackle the dual burden of communicable and non-communicable diseases—and bolstering WHO's work to provide technical guidance. As countries identify unique strategies for strengthening their health systems, WHO should continue to provide technical support and guide national governments on building resilient health infrastructure, workforces, and information systems. While increasing our focus on emerging threats, including non-communicable diseases, health emergencies, and health impacts of climate and environmental change, we must also continue to improve maternal and child health and maintain a strong focus on HIV, tuberculosis, malaria, and eradication of polio;

-

(2)

Ensuring strong, coordinated, and rapid global responses to health emergencies, including antimicrobial resistance. This includes working with countries to ensure the implementation of the International Health Regulations and strengthening WHO's capacity to lead and foster multisectoral collaboration. We must bolster our front-line defence against public health threats by supporting the development of robust health systems, particularly at the primary health-care and community levels, that can prevent disease outbreaks or identify them early, when they can most easily be contained. WHO must champion a “One Health” approach and work with partners across the human and animal health and environmental sectors to coordinate a much bolder global response to antimicrobial resistance. This begins with following up on the commitments Member States made at last month's United Nations General Assembly meeting on antimicrobial resistance. We must also ensure developing countries have access to the newest medicines as they are developed;

-

(3)

Promoting evidence-based decision making and awareness for preventing, mitigating, and responding to the health impacts of climate and environmental change. We must develop transformative new policies and innovations, as well as community-based and multisectoral approaches, to meet these emerging challenges. We must also ensure that efforts to better understand and combat the health effects of climate and environment change are well financed.

(5) What does sustainable development mean to you, and how can WHO make the greatest contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals?

Sustainable development is about making investments that help people lead healthy and productive lives and, in the long term, create well-functioning communities and robust economies. It cannot be achieved without good health. When people are healthy, they are productive, and entire families, communities, and nations thrive. I saw the ripple effect of good health first-hand when I was Minister of Health of Ethiopia. Even with limited resources, we invested in critical health infrastructure, expanded the health workforce, and initiated pioneering financing mechanisms. These reforms helped provide tens of millions of Ethiopians with access to health services, setting us on a path to achieve ambitious health—and broader development—targets and sustain and build on our successes for years to come.

I believe the world's commitment to sustainable development—enshrined in the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—offers a unique opportunity to improve the lives of people everywhere. WHO must work alongside governments and regional organisations—in close collaboration with civil society, private sector, other UN agencies, donors, and other key stakeholders—to drive the implementation of the health objectives of the SDGs and help countries achieve their targets by 2030.

(6) WHO lost credibility over its handling of the Ebola virus outbreak. What must WHO do to rebuild the trust of governments and their citizens?

After the Ebola crisis, WHO launched serious reforms aimed at improving its ability to respond more rapidly and effectively to public health emergencies, whenever and wherever they may arise. I will implement those reforms with a sense of urgency to build confidence among governments and their citizens that we are committed to being the world's foremost technical and political leader on public health emergencies. I will focus on building systems that allow WHO to rapidly deploy resources and scale up to the appropriate level of response, as well as on creating flexible and reliable funding mechanisms to ensure that WHO's ability to pay never hinders its ability to respond. I will continue our work with governments to implement the International Health Regulations so health systems are in place to detect disease outbreaks early, when they are easiest to contain. With this focus on quick wins and medium-term and long-term results, I am confident that we can regain trust around the world.

(7) Does WHO need further reform? If so, what reforms would you implement?

To deliver results, we need a strong, effective WHO that works together at all levels—from Geneva to regional offices and national capitals to local communities. Reforming the organisation will require vigilance, adaptability, and continual reflection.

I am committed to reviewing and refining WHO's ongoing governance and managerial reforms. Striking a balance between reform and stability of the organisation, I will specifically focus on the following areas to deliver results: enhancing the predictability and flexibility of WHO's financing; attracting and retaining the best talent from all parts of the world by creating an engaging and motivating environment; fostering innovation; and improving institutional effectiveness, transparency, and accountability. I will seek innovative partnerships with state and non-state actors, as I strongly believe that effectively tackling the health threats of our time requires united forces.

(8) What are the biggest threats facing WHO in the next 5 years? How will you address these threats?

One of the biggest challenges the WHO faces is the lack of flexibility and predictability of its funding. The annual budget of the organisation is smaller than single medical centres in big economies, and much of its funding comes from voluntary, earmarked contributions. We must be more strategic with what has already been committed, with a focus on value for money, while also pursuing innovative financing solutions and dialogues with Member States and key non-state contributors. I will also establish an Inter-Ministerial Advisory Commission—composed of Ministers of Health, Finance and International Development—to solicit advice, innovative solutions, and recommendations on assessed financial contributions from Member States.

Another challenge is the difficulty of predicting health emergencies and public health threats and of ensuring the agency is prepared to mount rapid and appropriate responses to these threats. This is an area where WHO has begun implementing reforms, as evidenced by its new Health Emergencies Programme, which aims to help countries prepare for, prevent, respond to, and recover from emergencies quickly. I will implement and independently monitor this new programme, while engaging with new mechanisms like the recently established Global Health Crisis Taskforce.

In addition, WHO must attract and retain the best talent and determine the appropriate mechanisms for doing so inclusively. I plan to review, nurture, and refine WHO's ongoing governance and managerial reforms to create an engaging and motivating environment for staff. I will also bring my open-door approach to management to encourage transparency, communication, and collaboration across all levels of WHO.

(9) Should WHO be a leader in health or should it only respond to the wishes of Member States?

WHO has to do both. These roles are not mutually exclusive. WHO should respond to the requests of Member States based on their health priorities and needs. In addition, WHO and its Director General should also proactively put forward a vision that mobilises Member States and other stakeholders, including civil society and the private sector, to ensure the health of people everywhere.

(10) What unique skills would you bring to the job of WHO Director-General?

My career has given me a unique mix of political leadership experience and hands-on public health experience. Because I have worked at all levels—from the community to the highest levels of national and global governance—I understand the challenges faced at the local level and the changes that must be made at the national and global levels to address them and deliver results.

As Ethiopia's Minister of Health, I learned first-hand what it takes to revitalise a weak health system with limited resources. We created 3500 health centres and 16 000 health posts to improve access to basic health care across the country. We trained and deployed 38 000 health extension workers at the community level—a model that has been replicated in more than a dozen countries across Africa. We built 30 new medical schools, leading to a 20-fold increase in the number of doctors trained each year. And we tackled stock-outs of essential medicines, transformed weak information systems and poor health data collection, increased country ownership of health programmes, and encouraged more effective donor harmonisation. Together, these successes helped Ethiopia dramatically expand access to health services and meet ambitious health targets. Notably, we reduced child mortality by two-thirds, maternal mortality by 69%, HIV infections by 90%, malaria mortality by 75%, and mortality from tuberculosis by 64%.

Through my engagement with global health initiatives, I have also gained invaluable experience in global health diplomacy. For example, as Chair of the Global Fund's board, I provided oversight on the organisation's comprehensive reform agenda. As Minister of Foreign Affairs, I brought together 193 UN Member States to agree to the Addis Ababa Action Agenda at the Third International Conference on Financing for Development in July, 2015. This was an historic milestone, forging a global partnership to achieve and finance the SDGs, including those related to health. In 2013, as Chair of the Executive Council of the African Union, I spearheaded the drafting of Agenda 2063, a global strategic framework aimed at accelerating Africa's economic, political, and social development through regional cooperation and solidarity. I also played a key role in resolving regional conflicts and overcoming political and cultural tensions that once impeded collaboration.

I am proud that my candidacy for WHO Director-General has been endorsed by the African Union. I am confident in my ability to lead WHO in a new era and serve as a champion for the health of all people, regardless of who they are or where they live.

Flavia Bustreo

Italy

© 2016 University of Essex

The greatest injustice of our time is that millions of adults, adolescents, and children around the world die unnecessarily from preventable causes for which there are evidence-based interventions. Millions more fail to reach their full potential for health and wellbeing, which also constrains their contributions to social and economic development. Many of the millions of refugees and internally displaced people in the world do not have access to basic services. Where is the equity for these people? Where is their human right to the highest attainable standard of health, as enshrined in the WHO Constitution and numerous human rights treaties?

In my life, I have been inspired by the transformative power of science, knowledge, and international partnerships in WHO's work that eradicated smallpox by 1980 and halved preventable maternal and child mortality during the Millennium Development Goals (MDGs). The collaborative efforts of WHO and partners have pushed through life-saving innovations such as the first-generation Ebola vaccine, and established the landmark WHO Framework Convention on Tobacco Control. We now have to channel this power to address critical inequities to realise the central promise of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs)—leave no one behind.

I can summarise my vision for WHO's work in five words: Equity, Rights, Responsiveness, Evidence, and Partnership. Five words, but charged with so much meaning and power for global health.

If we are serious about achieving SDG 3 through universal health coverage, we must unite around equity and rights, and use WHO's unparalleled convening power to bring together the scientific evidence and mobilise global partnerships. This will enable WHO to be more responsive to countries' needs related to current and emerging health threats, including non-communicable diseases and antimicrobial resistance. Most importantly, it will drive a sustained response to disease outbreaks and humanitarian emergencies, which deprive the most vulnerable of their health and their dignity. Currently, health has become an issue no national government can address alone, as the Ebola epidemic and increased migration have so acutely demonstrated. Global health security begins with intense surveillance in the most remote corners of the world, able to detect the appearance of new pathogens or the mutation of existing ones, but is only possible if governments collaborate with WHO to share the findings of this surveillance and act together in a WHO-coordinated response.

Fortunately, much of this is already beginning to happen. In my role as Assistant Director-General, Family, Women's and Children's Health at WHO, I worked closely with colleagues at WHO and the Office of the High Commissioner for Human Rights to set up the High-Level Working Group on Health and Human Rights, and will continue to support its work whole heartedly. The WHO Health Equity Monitor team working with global partners have developed resources to help countries assess inequalities and incorporate the results into planning. I was privileged to play a leading role in the collaborative effort to develop the Global Strategy for Women's, Children's and Adolescents' Health (2016–2030) launched by the UN Secretary-General and world leaders as a frontline implementation platform for the SDGs. With its predecessor strategy and accompanying Every Woman Every Child movement, it is one of the most powerful global health initiatives—raising more than US$60 billion since 2010, with multi-stakeholder efforts contributing to the unprecedented progress to end preventable mortality and promote health and wellbeing. And we can all see the huge potential in the landmark climate change agreement in Paris, where WHO's work with partners on the scientific evidence helped mobilise political commitment to explicitly recognise the links between climate change, equity, and the right to health in the agreement.

We need much more of this kind of concerted, high-level collaboration to embed equity and rights, responsiveness, evidence, and partnership at the core of global health and WHO's work. I am very proud that the Government of Italy presented my candidature for WHO Director-General so this can happen under my leadership for the benefit of the health and wellbeing of people in all countries.

(1) What would be your priorities as Director-General of WHO?

We need to drive progress towards achieving the health SDG as a cross-cutting driver of sustainable development, enhancing policies in other sectors that are crucial determinants of health and to which health contributes, for example education, energy, water, sanitation and hygiene, and infrastructure development.

We must expand universal health coverage for proven, evidence-based health interventions, building on the progress in HIV, malaria, tuberculosis, and MDG 4 and 5, with tools for assessing and treating newer global health priorities such as cancers and NCDs.

We must drive the reform of WHO to more effectively support Member States as they respond to health emergencies and outbreaks, such as the devastating Ebola outbreak, Zika, yellow fever, and the new threats of antimicrobial resistance.

We must address the impact of climate change on the health of citizens, mediated through the changing patterns of diseases vectors, disruption in access to food, safe water, and clean air. And make WHO, and the health sector as a whole, carbon neutral.

We need to prioritise the health of women, children, and young people everywhere—especially to reduce the impact of ill health due to migration and crises—improving their nutrition and wellbeing across the life course and addressing remaining gaps such as stillbirths.

We must maximise efforts to achieve equity using a human-rights-based approach in health and sustainable development.

(2) WHO cannot do everything. What should WHO not do?

WHO should not try to duplicate the functions of its Member States that are represented on the organisation's governing bodies by ministries of health. Countries should assess their own health needs and develop and implement their own plans to strengthen health systems and improve the health of citizens; the role of WHO is to support Member States in these efforts. WHO should lead global health and bring together all stakeholders, without duplicating what others can do.

(3) What are the three biggest threats to the health of peoples across the world?

At macro level the three biggest health threats are: (1) epidemics and humanitarian emergencies, which compound poverty and the striking inequities in income and social status across the world; (2) the slowness of the international community, to date, in recognising and addressing the strong links between ill health and climate change; (3) overlooking the demands and contributions of demographic changes in countries, most notably due to population ageing.

(4) What would you do to tackle those threats?

To respond to epidemics and humanitarian emergencies, WHO has currently embarked on significant reforms to become more operational, coordinate centrally in one programme, and strengthen surveillance and adherence to the International Health Regulations by Member States. I will advance the reform aggressively, adjusting to the findings of evaluations and maintaining a constant vigilance on the emergence of new threats and pathogens, such as antimicrobial resistance and the Zika virus.

In 2015, the WHO Executive Board endorsed a new work plan on climate change and health. We need to implement and further develop this work plan to ensure health is properly represented in the climate change agenda and to raise awareness of threats that climate change presents to human health. We also need to coordinate reviews of the scientific evidence on the links between climate change and health, and develop a global research agenda. Member States are working to reduce their health vulnerability to climate change, and to promote health while reducing carbon emissions; WHO must play an important role in supporting this activity.

Comprehensive public health action and investment to address population ageing is urgently needed around the new concept of functional ability (which is a product of a person's intrinsic physical and mental capacities and their interaction with environmental factors). Making these investments will have valuable social and economic returns, both in terms of the health and wellbeing of older people and in enabling their ongoing participation in society.

(5) What does sustainable development mean to you, and how can WHO make the greatest contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals?

The SDGs provide an opportunity for WHO to act on what the recent evidence clearly shows—that health and sustainable development are closely inter-related. Health contributes to social and economic development and other sectors contribute to health. WHO needs to amplify its ongoing work within health and with other sectors to tackle shared challenges and achieve common goals.

Sustainable development is self-perpetuating. In health terms, that means that every health intervention or programme should not only deliver benefits today, but also into the future. In the past, this is where the health community has often failed, saving a child's life with timely intervention during childbirth, but then not doing enough as that same child fell ill from a lack of essential nutrition or vaccines. Assuming the same child survived, they may have developed habits in adolescence that are associated with the burden of non-communicable diseases in adulthood, and may have experienced the lack of universal health coverage to support their healthy ageing. In this way, millions of people irretrievably lose the opportunity to achieve their full potential for health and wellbeing across their life.

A sustainable approach to health requires integrated health care across the life course, with support from sectors outside the health sector—such as water, sanitation, education, and finance—which can help create an enabling environment for health (a key ingredient for sustainability). This will entail a massive amount of cooperation between multiple partners and stakeholders. As WHO is ideally situated to facilitate and improve global cooperation on health, its greatest contribution to the SDGs may be as a facilitator of coordinated multi-stakeholder action.

(6) WHO lost credibility over its handling of the Ebola virus outbreak. What must WHO do to rebuild the trust of governments and their citizens?

The experience from the Ebola outbreak has highlighted the weaknesses of health system capacity in the three countries mostly affected, Guinea, Liberia, and Sierra Leone, but also the slow global response to prevent further spread of the outbreak. As noted earlier in answer 4, WHO has currently embarked on a significant reform to become more operational, coordinate centrally in one programme, and strengthen surveillance and adherence to the International Health Regulations by Member States. I will advance the reform aggressively, adjusting to the findings of evaluations and maintaining a constant vigilance on the emergence of new threats and pathogens, such as antimicrobial resistance and the Zika virus.

(7) Does WHO need further reform? If so, what reforms would you implement?

Further reforms are essential. WHO needs to get better at responding to health issues as they emerge and to the opinions and needs of the people it serves, and to become a more effective, transparent, and accountable organisation, with streamlined decision-making processes. Looking outwards, it needs to drive support for innovation and research—including through its normative standard setting function—in medical science, technology, policy, business, the social sciences, and health financing. It must strive to create an enabling environment for innovation and health by helping to match innovation to global health needs and mitigating the risks of innovation investment through forward-looking partnership models with Member States, the private sector and others, without compromising its integrity.

WHO's function as a knowledge provider and facilitator needs strengthening. The organisation must meet the knowledge needs of countries by facilitating global knowledge sharing and evidence synthesis and response to policy needs. And it needs to expand its own knowledge base, for example by understanding the changing funding landscape for the achievement of the highest attainable mental and physical health for citizens, especially the growing role of in-country financing.

(8) What are the biggest threats facing WHO in the next 5 years? How will you address these threats?

The biggest threat to WHO is that it fails to respond to the changing needs of Member States and their citizens. For example, low-income and middle-income countries are increasingly aiming to develop domestic sources of health funding. WHO needs to understand how this will change the global health landscape. To support WHO Member States in identifying and responding to epidemics and other public health threats, in the most effective and timely way possible, WHO needs to marshal its technical support across departments and set up strategic partnerships with other agencies and partners.

(9) Should WHO be a leader in health or should it only respond to the wishes of Member States?

WHO comprises both Member States and the secretariat. In my experience, Member States want WHO, as a collective, to provide leadership to implement the organisation's mandate in health, and to address health challenges that no single Member State can. This requires collective action, which Jamison et al. define as “an economically rational approach to provision of public goods from which all can benefit…international collective action responds to opportunities of which benefits cover many nations”. However, this is not to say that WHO should dictate to individual Member States. Rather it should use its unique capacity as a global convenor to generate consensus on which to base collective action. WHO should always bear in mind the priorities and wishes of Member States and their citizens, and their sovereign right to decide how national health policy is implemented.

(10) What unique skills would you bring to the job of WHO Director-General?

My unique position as the only WHO internal candidate is one of the key strengths as a candidate for the role of Director-General, and through my extensive work with governments and multi-stakeholder partnerships also clearly perceive global health issues from perspectives outside the organisation too. I believe that these twin perspectives are necessary to effectively lead WHO.

As the only WHO internal candidate, I bring in-depth management experience and extensive knowledge of the organisation—the pitfalls and dynamics and the strengths and weaknesses—and have driven reforms and innovation, mainstreaming of gender, equity, and human rights across the entire organisation. I have supported and collaborated closely with WHO staff, our most precious assets, hired real talents in the leadership of my team, and have demonstrated the ability to raise significant financial resources (my cluster is the best funded in WHO).

In addition, my experience as medical doctor and epidemiologist working in many countries, as well as the close engagement in multi-stakeholder partnerships, gave me the opportunity to learn how to clearly perceive global health issues from the perspective of external partners.

As a medical doctor and epidemiologist, I acquired first-hand experience of public health in numerous settings, including post-war, epidemics and outbreaks, and internal and external migration. I have contributed to setting up surveillance systems to detect pneumonia and diarrhoeal diseases in countries of the former Soviet Union, as well as the first global antimicrobial surveillance for drug resistance tuberculosis in the world, and response to meningitis and cholera outbreaks in Sudan.

Partners have valued my leadership skills to build partnerships, such as the creation and leadership of the Partnership for Maternal, Newborn and Child Health (PMNCH), and achieve consensus in complex, multi-stakeholder and multi-country contexts, and appreciated my political vision that has helped set far-reaching agendas for health, without settling for a minimum common denominator.

I have had the honour to work with the highest level of governments, presidents and prime ministers, ministers of health and finance, parliamentarians, to forge for example the G7 Muskoka initiative in 2010 and the African Union initiative on women's and children's health. My jobs outside of WHO—for example at the World Bank, at Gavi, and as an adviser to the Prime Minister of Norway—have given me a clear understanding of the arguments needed to prioritise investments in health and health systems both domestic and internationally. I have a track record of achieving increased political and financial commitments and setting up systems for accountability and transparency. These accomplishments have also been characterised by advocacy for greater participation of civil society, such as the Citizen Hearings for women's and children's health, and especially greater youth engagement in decision making for health.

I have been closely engaged with the scientific community and media through publishing in the medical, political, and foreign affairs journals, as well as in the mainstream media and social media from The Lancet to the Hindustan Times. In addition to almost 100 peer reviewed articles in leading scientific journals, book chapters, I have a regular blog with Huffington Post and a vibrant Twitter following.

In conclusion, I have proven unique skills and experience to harness the power of evidence and advocacy to mobilise political commitment and resources for health. I am honoured to put these skills and experience at the service of the global health community to take on this new challenge and to ensure that WHO can achieve the international commitment to the right to the highest attainable standard of health for all people.

Philippe Douste-Blazy

France

© 2016 Stephane Cardinale-Corbis/Contributor

As a candidate for Director-General of WHO, I wish to see WHO effectively fulfilling its mandate as the leading organisation in global health and consistently promoting health not only as a human right, but as the right choice for governments in a world of competing demands and interests. As Director General, I will be dedicated to working within the global system to finance and promote pragmatic, long-term solutions to the root causes of poor health and inequality, and to ensuring that action on health is a major driver of progress towards sustainable development as a whole.

My vision for WHO is focused on three goals: reform, responsiveness, and results.

My reform agenda will begin with the development of a comprehensive organisational vision and strategy negotiated with Member States. This will ensure that WHO is focused on the most important challenges in global health today and has coherent plans to address them. Secondly, the organisation must function more cohesively, with continuous dialogue and clear lines of accountability between the Director-General, Regional Directors, and country offices. This cohesiveness can be achieved through strong political leadership and technical proficiency from headquarters, supported by more explicit delivery agreements between different levels of the organisation. Thirdly, WHO must be more proactive and strategic in its fundraising to ensure that it has more predictable and sustainable funding. Drawing upon my experience in innovative financing for development, I will work to develop new sources of revenue that supplement Member State contributions and non-core funding to support the essential, core functions of WHO.

Under my leadership, WHO will demonstrate a strong culture of responsiveness, especially with regard to health emergencies, drawing upon the difficult lessons of Ebola and other recent health crises. The world cannot afford and will not tolerate a WHO failure in this core area of its mandate. The Health Emergencies Programme (HEP) must be quickly scaled up, with clear lines of authority, effective functional links with other parts of the organisation, and a commitment to continuous learning and improvement. While the HEP is a major priority in creating a more responsive WHO, the organisation must exhibit a culture of responsiveness in all its work, including its action on non-communicable diseases and their social and environmental determinants, as well as its efforts to tackle new challenges posed by the HIV, tuberculosis, and malaria epidemics.

WHO must be more consistently focused on results. Its resources must be clearly directed to the global health priorities agreed to by Member States and the organisation needs to more consistently demonstrate that it is achieving impact. This can be done by ensuring a stronger emphasis on value for money, strengthening performance and management data, and linking the budget more closely to results and impact.

Finally, WHO must be focused on its core responsibilities at global and country levels. Its essential roles at the global level are to convene multiple stakeholders (including civil society and the private sector), build strong alliances to improve health outcomes and address the social, economic, and environmental determinants of health—especially for the poorest and most vulnerable—and to develop consensus on health policies, norms, and standards. At the country level, WHO must continue to be the organisation that Member States respect and depend on for the highest standards of evidence-informed guidance and advice, based on country needs and promoting country ownership.

As a physician and an experienced public sector manager and political leader, I believe I am well equipped to provide the leadership that will restore and maintain WHO's essential role in global health.

(1) What would be your priorities as Director-General of WHO?

As Director-General, I would specifically promote WHO leadership and action in the following five priority areas: (1) ensuring that WHO responds effectively to emerging and re-emerging infectious diseases; (2) tackling the unprecedented growth of non-communicable diseases; (3) bolstering health systems to implement universal health coverage; (4) increasing the availability, affordability and access to essential medicines; and (5) tackling the growing challenge of antimicrobial resistance.

Sustained attention to maternal and child health and increased attention to mental health will also feature prominently on my agenda.

(2) WHO cannot do everything. What should WHO not do?

WHO should remain an organisation that coordinates global health actors, develops consensus on health strategies, norms, and policies, and provides support to countries for their implementation. It should not itself act as an implementing or funding agency or engage in project management.

WHO should not impose on countries strategies or programmes that have been elaborated without their full participation, that are not likely to be funded, and/or that impose additional bureaucratic requirements on countries' health governance and systems.

Internally, WHO should avoid duplication of activities at different levels of the organisation and initiatives that are independent of the overall vision and strategy for the organisation that is agreed to by Member States. Clusters/departments should only be structured in such a way as to align with the organisational vision and strategy.

(3) What are the three biggest threats to the health of peoples across the world?

The three biggest threats to people's health globally are: (1) the persistent risk of emerging epidemics; (2) the increasing prevalence of non-communicable diseases, driven by social and environmental factors; and (3) diminishing global solidarity and attention to health and health commodities as global public goods, in the context of a globalisation that is largely market-driven and marked by growing global political tensions.

(4) What would you do to tackle those threats?

-

(1)

Scale up the Health Emergencies Programme and ensure that it has sustainable funding; strengthen surveillance and country and regional preparedness for disease outbreaks; integrate lessons from recent health crises; ensure strong coordination across the UN and effective partnership with non-government actors;

-

(2)

Ensure strong WHO leadership in response to NCDs with a clear recognition that over 90% of premature deaths from NCDs occur in low-income and middle-income countries; develop evidence based normative guidance with a strong focus on prevention and addressing major risk factors, including tobacco use and obesity; and

-

(3)

Provide strong political leadership to promote public health and access to medicines and other health commodities as global public goods within the context of universal health coverage, with a focus on building equitable, people-centred, and responsive health systems.

(5) What does sustainable development mean to you, and how can WHO make the greatest contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals?

Sustainable development is development that strikes an appropriate balance between different—and often competing—needs, while ensuring that all development efforts are as synergistic and mutually reinforcing as possible and that development efforts today do not compromise the choices available to future generations. Effective leadership by WHO within the sustainable development framework should not only focus on fighting diseases, promoting wellbeing, and strengthening health systems (SDG 3), but also link with and contribute to other key development goals such as progress against poverty, inequality, social exclusion, environmental degradation, and related determinants of health.

Key priorities for WHO in the context of the SDGs must include actively reviving mobilisation around global public goods that are key to sustainable development, implementation of universal health coverage, strengthening primary health care, and the effective implementation of the International Health Regulations. The SDGs also present an historic opportunity to further emphasise the importance of health within national development strategies and plans.

(6) WHO lost credibility over its handling of the Ebola virus outbreak. What must WHO do to rebuild the trust of governments and their citizens?

As noted in earlier responses, WHO must increase the effectiveness of its responses to health emergencies through fast and effective implementation of the Health Emergencies Programme. More generally, WHO must develop and promote a more strategic vision on health and serve as a tireless advocate for health in the face of competing interests. The organisation must continue to show leadership as the principal coordinating and convening body in health; support multi-stakeholder dialogue, including by showing increased openness to actors from civil society and the private sector; and remain the world's leading builder of consensus on evidence-based approaches and normative guidance.

(7) Does WHO need further reform? If so, what reforms would you implement?

As described in my overall vision at the beginning of this message, key reforms required are the development of an organisational vision and strategy negotiated with Member States; increased coherence and improved lines of accountability across the three levels of the organisation; more predictable and sustainable funding; and increased accountability through more effective linking of budget with performance, results and impact.

(8) What are the biggest threats facing WHO in the next 5 years? How will you address these threats?

The three biggest threats facing the organisation are: (1) loss of confidence in the organisation as a result of suboptimal performance and consequent decreases in funding; (2) institutional complacency and drift deriving from a lack of strategic vision and focus; and (3) as a result of (1) and (2), further fragmentation of the global health architecture.

As discussed in earlier responses, these threats need to be addressed by implementation of further reforms and development of a strategic vision and focus for the organisation negotiated with Member States.

(9) Should WHO be a leader in health or should it only respond to the wishes of Member States?

As the sole international organisation with universal legitimacy on global health, WHO should lead in developing a global vision to tackle the current and future challenges in global health. Political leadership and multi-stakeholder engagement are needed to build consensus among Member States and their citizens on that vision.

(10) What unique skills would you bring to the job of WHO Director-General?

As a former minister of both Health and of Foreign Affairs, I will bring the strong political and diplomatic leadership skills that are essential to WHO at this key moment in its history and I will consistently make the political case for health as an investment in sustainable development, rather than an expense.

As a former mayor of Toulouse, I have managed an annual budget of US$1·5 billion and 30 000 employees, comparable to the budget and exceeding the workforce of WHO. I will bring strong administrative and management experience to this role.

As the Founder and Chair of UNITAID and the UN Secretary General's Special Envoy on Innovative Financing for Development, I have contributed to creating the first source of innovative finance for health, and I will bring a history and practice of innovation to the leadership of WHO.

David Nabarro

UK

© 2016 Anadolu Agency/Contributor

Our world is challenged by a changing climate, violent conflict, persistent poverty, and mass migration. The benefits of globalisation and new technologies remain unequally shared. As a result, people face an ever-growing avalanche of threats to their health. I have worked on such issues for over 40 years. As I see it, the need for a robust, reliable, and responsive WHO has never been more urgent.

I am honoured to be presented as a candidate for the position of Director-General. All my professional life I have been working in public health—as a community-based practitioner, educator, public servant, director, diplomat, and coordinator. In the past 12 years, successive Secretaries-General of the United Nations have entrusted me to lead collective action on pressing and complex challenges—responding to avian and pandemic influenza, promoting food security, ending malnutrition, combating Ebola, promoting the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, and advancing efforts relating to climate change.

I have the experience and skills needed to serve WHO as Director-General: I will focus on four key priorities:

-

(1)

Alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs). The 2030 Agenda offers a clear roadmap for a more peaceful, equitable, and prosperous future within communities and nations. Health is central to the achievement of the SDGs. As a result of my experience in the last year I am ready to ensure that WHO is well positioned for this new era: I will encourage horizontal, cross-disciplinary, intersectoral working that yields measurable results;

-

(2)

Transforming WHO to respond to outbreaks and health emergencies. In times of outbreaks and health emergencies, WHO is expected to exercise leadership by providing unparalleled technical expertise, while empowering others to act. I have led inter-agency efforts to combat disease threats and outbreaks (including malaria, avian influenza, Ebola, Zika, and cholera). In 2015–2016, I chaired the Advisory Group on the Reform of WHO's Work in Outbreaks and Emergencies. I am committed to completing the work needed to solidify WHO's capacity to respond to outbreaks and health emergencies.

-

(3)

Trusted engagement with Member States. National authorities have the primary responsibility to promote the health of their people, but health objectives cannot be achieved without the full engagement of people and civil society, as well as decisive leadership and strong commitment from governments. WHO needs to be a trusted partner of all governments while holding itself to the pledge that world leaders themselves made in the 2030 Agenda to leave no one behind. I have consistently sought to engage with Member States in ways that are respectful and reliable, consistent, transparent, and accountable.

-

(4)

Advancing people-centred health policies. Ever since the Primary Health Care Movement in the 1970s, WHO has advocated people-centred policies for health. Implementation depends on there being spaces in which organisations working for people's health engage openly with other stakeholders. It calls for consistent attention to the capabilities and circumstances of care providers. I continue to champion the interests of all who work to sustain people's health everywhere—including within households, communities, work-places, health-care facilities, and institutions.

(1) What would be your priorities as Director-General of WHO?

As the Director-General of WHO, I would ensure that WHO can deliver in four areas: (1) alignment with the Sustainable Development Goals; (2) transforming WHO to respond to outbreaks and health emergencies; (3) trusted engagement with Member States; and (4) advancing people-centred health policies.

The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development—with its focus on equity, inclusiveness, and leaving no one behind—builds on the spirit of Primary Health Care, championed by WHO's Member States for four decades. WHO's contribution to the SDGs should include: enabling all people everywhere to attain the highest possible standard of health; continuing attention to health's economic, social, political, and environmental determinants; completing the unfinished work for the Millennium Development Goals; addressing the growing challenge of non-communicable diseases; and ensuring universal access to effective health services, medicines, technologies, and financial protection. In all my work within the UN system I have encouraged horizontal, cross-disciplinary, intersectoral working and have advocated whole of government and whole of society approaches that will be needed to address the SDG health agenda.

Ensuring capacity to prepare for and respond to disease outbreaks and health emergencies will always be a key priority of WHO. It must do this in ways that are predictable, robust, and reliable, and that reflect the interests of all nations and peoples. This will include developing national capacities in line with the International Health Regulations; encouraging strategic research and innovation; urgent strategic action on antimicrobial resistance; giving special attention to the needs of vulnerable and threatened communities—including those who seek to move and take refuge so as to escape suffering; and reinforcing effective global responses to severe health crises. I intend to complete the work needed to secure WHO's credibility as an organisation with both the normative excellence and the operational agility needed to lead responses to health crises.

When engaging with Member States, WHO should be seen as the strategic leader, innovator, catalyst, and convener for people's health. WHO should do this in ways that reflect both current realities and the needs of coming decades. This requires a culture that constantly heeds the interests and concerns of Member States and their people; that leads through empowerment and example, that engages with all other actors and thought leaders committed to promoting health and health equity, and that encourages all concerned to trust the effectiveness and responsiveness of WHO.

In advancing people-centred health policies, WHO should serve as a champion for the interests, wellbeing, and capabilities of all health-care providers. WHO should intensify efforts to ensure the effectiveness of health caregivers, encouraging skills development and competency testing, and protecting the interests (and physical safety) of all who sustain people's health in households, communities, workplaces, health-care facilities, and institutions.

Community engagement and inclusive partnering will be critical for each and every one of these priorities. I have seen the importance of community ownership and engagement in all my professional work. I have seen how Ebola eventually caused families to change how they buried their dead, and appreciated the heartache caused by this profound change of practice. I see how Zika now challenges women to reconsider when they become pregnant. These decisions on how a person comes into the world, how they leave it, and how they are supported when they are ill are the most intimate decisions people make and often reflect firmly-held belief systems. That is why people and their representatives (civil society, faith leaders, traditional leaders, and women's groups) need to be engaged, and listened to, whenever health policies are being shaped and implemented.

Inclusive partnering means engaging in broad coalitions and nurturing movements for transformative change. It will require transparent handling of multiple interests and encourage guaranteed and inclusive involvement of less powerful but vitally important stakeholders—be they small nations, minority groups, people with special needs, or those who are so often neither seen nor heard, and are often left behind.

(2) WHO cannot do everything. What should WHO not do?

Policy decisions as to what WHO should (or should not) do will be made by Member States. In principle WHO has to be prepared to help countries address any threat to their people's health. Situations will arise when WHO takes the lead on specific issues. But usually WHO provides technical support to national authorities as they address specific health issues: in these situations WHO may also serve as a catalyst, facilitator, or convener. This calls for strategic leadership that is both confident and effective—to define priorities, support those responsible for implementation, and establish the roles of different actors.

Global stewardship is important. It means drawing on the strengths of all of WHO. As Director General, I will encourage each of the levels of WHO to contribute according to their respective strengths, ensuring clear delineation of responsibilities and accountability for the use of resources. I will do this at all times in conjunction with the Regional Directors and their teams.

(3) What are the three biggest threats to the health of peoples across the world?

-

(1)

Poverty, inequality, and weak governance: people's health is undermined if they do not have reliable access to adequate income, nutritious food, water, sanitation, and shelter. These factors are further exacerbated when there is conflict, political instability, fragility, abuse of human rights, and inequitable economic growth. In combination, these factors contribute to the breakdown of basic health systems, a lack of basic needs, inadequate financial protection and—inevitably—a further spiral of ill health and poverty.

-

(2)

Existing and emerging infections: outbreaks of infectious disease undermine economies, society, and stability: hence the need to promote health security, and reduce risks due to HIV/AIDS, malaria, tuberculosis, diarrhoeal diseases, and other existing infections. With hotter temperatures, heavier rainfall, increased urbanisation, and changes in livestock production, patterns of disease incidence alter. This results in increased risks of people being affected by vector-borne and zoonotic diseases with epidemic potential.

-

(3)

Low priority for health and health care: if health not given sufficient attention in global, national, and local governance and policy making, people are more likely to face serious illness and to become poorer as a result. This can be the case when levels of investment in health are low or inequitable; when competing economic interests undermine health; when there is no cross-sectoral action for health or when there is insufficient investment in opportunities for physical activity and nutrition among young people. Such policy deficits can increase risks of illness arising from climate change and undermine efforts to address NCD risk factors. Challenges will be even greater if there is insufficient attention to the growing threat of antimicrobial resistance.

(4) What would you do to tackle those threats?

Three elements are critical—the 2030 Agenda, the One Health Approach, and political advocacy.

The 2030 Agenda offers a framework for establishing positive linkages between health and the other Sustainable Development Goals. It will be important for WHO to ensure that attention is paid to health when policy makers take decisions on how they deal with migrants, how to conduct war, how they regulate the environment. WHO will need to encourage and support an all of government approach, making sure that ministries of health are working alongside ministries of sanitation, social welfare, and security.

Similarly, the One Health approach focuses on the issues that emerge at the interface between animals, humans, and the ecosystems in which they live. This is evolving into the concept of planetary health that seeks to integrate human health within ongoing dialogues on climate-compatible economic growth, resilient livelihoods, sustainable infrastructure, the future of land and oceans, urbanisation, and industrial development. Examination of the connections within different settings quickly exposes immediate or potential opportunities for health improvement through action in sectors and disciplines other than health.

Finally, WHO will always need to be an advocate for health outcomes: elevating and maintaining health as a priority on political agendas at all levels. In recent years, political groupings such as the African Union, Association of Southeast Asian Nations, the European Union, the G7 and the G20, as well as the United Nations, have increasingly focused on health as a priority. It is important that WHO plays its part in such settings to explain, interpret and be ready to advance issues as leaders provide political impetus for health. Antimicrobial resistance was highlighted in this way at the 71st UN General Assembly in New York in September, 2016.

(5) What does sustainable development mean to you, and how can WHO make the greatest contribution to the Sustainable Development Goals?

Sustainable development, as set out in the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development adopted by Member States, provides a universal framework to be pursued by all governments, businesses, civil society, and individuals everywhere. It is the plan for our common future—for people, planet, prosperity, and peace through partnership. Implementation of this agenda—in concert with other multilateral agreements on disaster risk, financing for development, climate change, migration, and antimicrobial resistance—can be expected to have a dramatic impact on people's abilities to be healthy and to access care in case of illness. This is a result of the connectedness of the 17 goals, though is explicitly set out in Goal 3 with its emphasis on universal health coverage.

As discussed above, WHO's contribution to the SDGs should include: enabling all people everywhere to attain the highest possible standard of health; continuing attention to health's economic, social, political, and environmental determinants; completing the unfinished work for the Millennium Development Goals; addressing the growing challenge of non-communicable diseases; and ensuring universal access to effective health services, medicines, technologies, and financial protection.

(6) WHO lost credibility over its handling of the Ebola virus outbreak. What must WHO do to rebuild the trust of governments and their citizens?

The cultural, institutional, and organisational changes needed in WHO have been clearly set out in the report of the Advisory Group on Reform of WHO's Work in Outbreaks and Emergencies, a group which I chaired from 2015–2016. The changes suggested in this report have been internalised within WHO—and will be progressively reflected in the performance of country, regional, and headquarters offices. Implementation has started: it needs to be sustained in a continuous and consistent way with the support of the Independent Oversight and Advisory Committee that will provide recommendation on options for improvement. Over time, as new levels of performance are achieved and benchmarked, credibility and confidence will return, additional funds will be mobilised and WHO's contribution to outbreak prevention, preparedness and response, as well as in health emergencies, will reach the standard required by Member States.

(7) Does WHO need further reform? If so, what reforms would you implement?

Looking ahead, I see WHO as a magnet that attracts talented people, builds their skills over time and deploys them in ways in which they can be most effective. This is increasingly being achieved through skilful, empowered, and accountable managers at all levels of the organisation. I see WHO as an organisation that increasingly manages scarce funds creatively, transparently and with clear lines of accountability. I would also like to see these features of the organisation better advanced, appreciated and understood—within and outside WHO.

All multilateral organisations need constant transformation to ensure that their systems, priorities and processes are responsive to the changing political, technological, environmental, social, cultural and economic contexts of people's lives. I expect WHO to remain an active player in the transformation of the wider UN system in line with the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, seeking ways to ensure the relevance of individual agencies as well as coherence of international systems as a whole.

There will be times when substantive transformation is needed to tune up a particular aspect of an organisation's performance. This occurred during the 2014–15 Ebola outbreak. WHO has been affected by the criticisms it received in relation to handling complex disease outbreaks. The flexibility and willingness of professionals inside and outside WHO—adjusting effectively to new ways of working—has shown that WHO can function as an organic and adaptable entity.

Member States will continue to debate ways in which the governance undertaken by the Executive Board and the World Health Assembly enables the Secretariat to be more effective and contributes to the global influence of the WHO as a whole. There will remain the constant challenge of aligning finance to desired outcomes. This will include ensuring that any trade-offs in ways resources are allocated reflect the interests of people who are at risk of ill health and for whom illness has the greatest consequences.

The Director-General is expected to steer the process of transformation, to affirm priorities and to encourage partnering when this can be helpful. When Director General I will encourage WHO personnel to develop the collective capabilities and confidence they need to see their organisation as a technical leader that contributes to better lives for everyone. WHO is now moving in the right direction: the challenge is to help all who are within or associated with it to recognise the contributions they make. They should come to appreciate that although these contributions are never as great as they would wish, they should be confident that they are organising and partnering in ways that have substantial impact for people in many different places. Through their inspiration and example, I expect that WHO senior managers will continue to lead the process of transformation, and be partners with the Director General in achieving even more.

(8) What are the biggest threats facing WHO in the next 5 years? How will you address these threats?

It is likely that WHO will experience five major threats to its effectiveness.

-

(1)

Finance: with significant fixed costs, the effects of inflation and a static budget, it is difficult to increase both efficiency and effectiveness without any reduction in the tasks being undertaken. Dependence on specified voluntary contributions is inevitable, though it is important to ensure that these do not encourage the organisation to pursue activities that might be better carried out by others or that divert resources from higher priority activities that are less well-funded. The financing reforms initiated by the current administration, which focus on alignment, transparency, and impact, are moving in the right direction and should be sustained.

-

(2)

Locating and employing strategic leaders: WHO continues to depend on its human resources—maintaining a diverse pool of highly skilled and experienced experts who have the skills needed to work effectively with Member States. Volatile voluntary funding inevitably leads to widespread use of short-term hiring arrangements: this makes it difficult for managers to maintain these pools. Innovative means for accessing experts from national institutions (with appropriate geographical balance and diversity) should be sustained, with care to ensure they function within the WHO culture, norms, and operating procedures. Being a WHO staff member needs to be synonymous with both technical excellence and the ability to work effectively with national authorities.

-

(3)

Maintaining space for interaction, handling multiple interests, and sustaining integrity: multiple stakeholders are involved in global health. They include civil society networks, individual NGOs at international, national, and community level, professional associations, the media, think tanks, national and transnational corporations. They also now include articulate individuals and informal communities of advocates with strong voices and novel influence thanks to information technology, social media, and organisational skills. While this is a welcome development, this multiplicity of actors engage with WHO because they seek to influence decision making. This can be challenging both for WHO's Member States and for the Secretariat.

-

(4)

Governance: it is important to ensure the primacy of WHO's governors, the Member States, when policy decisions are made. It is also important to ensure that the expertise and independence of the Secretariat are protected when standard setting work is undertaken. And, given the increasing significance of multi-stakeholder working, it is important that safe spaces exist for all parties to interact. These spaces should enable the inclusion of those who might lack the power they need to ensure their voices are heard and presence is felt. I have substantial experience in partnering and fostering movements and appreciate the careful balance that is required to benefit from the work of multiple stakeholders, while maintaining the independence of the technical and normative functions that need to be undertaken from within the UN system.

-

(5)

Novel threats: the global health community has learnt to anticipate unexpected threats—whatever the cause. The transformation of WHO's work in outbreaks and emergencies will lead to a more predictable, agile, and effective capacity for action. This will always involve WHO working with other entities in ways that reflect comparative advantages. When an incident occurs and a response is triggered, pre-planned procedures should engage a broad range of operational entities, strategic partners and international political actors at the highest level. It is now well-recognised that simulations involving critical experts from within government, UN, NGOs, scientists, business, and media are invaluable. Results must be shared with world leaders at regular intervals so that they can appreciate states of readiness and institute necessary system changes to ensure that they are able to contain extreme threats to people's health and global stability.

(9) Should WHO be a leader in health or should it only respond to the wishes of Member States?

As strategic leader for world health, WHO needs to appreciate and be responsive to the needs of Member states and their people. This means that WHO needs to support national governments in the pursuit of health objectives, providing excellent technical advice, identifying gaps in national capacities, and engaging in political advocacy to ensure such gaps are addressed. At the same time, just as world leaders pledged to leave no one behind when they adopted the 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development, WHO must strive to listen and respond to all stakeholders, ensuring that the most vulnerable and those that are hardest to reach have access to quality health services.

In this context leadership is vital: it must be both strategic and sensitive. WHO's health leaders need to use diplomatic skills to broker constructive agreement and avoid gridlock when national interests diverge. They need to make it clear at the highest levels of government when States fail to honour international regulations in ways that impact on the health of their own or other populations. They need to use the power of evidence to hold up a mirror to states' performance. They should be ready to champion issues that are vital to the right to health while recognising that for some members these may be controversial. They must be able to accept criticism and acknowledge that their judgments will be questioned.

(10) What unique skills would you bring to the job of WHO Director-General?

I have extensive experience from work within communities in southeast Asia, east Africa, the Middle East, and Latin America. I have led a range of health and development initiatives, always analysing them from the perspective of their impact on the wellbeing of people, their households and their territories. I know the major organisations and players in global health, and have worked with many of them since their foundation. I have worked in senior positions within WHO and have experience of transforming work on outbreaks and emergencies. I offer a safe pair of hands in crises and am effective at bringing different actors together so they work in synergy. I have developed the ability to work with world leaders in fostering partnerships and collaborative environments through which diverse interests and actors come together in pursuit of common goals and measure their achievements. I enjoy that aspect of my work very much indeed.

My leadership within WHO has included roles on malaria control, environmental health, health emergencies, and the office of a previous Director-General. I understand the challenges of managing transformation in WHO and know that success calls for working effectively across all levels and elements of the organisation in ways that enable all to contribute effectively. I have senior management experience within a major donor government and understand the world of bilateral development agencies. As an adviser to successive Secretaries-General, I have become familiar with many aspects of the UN system and ways in which it can contribute to advancing personal, community, national, and international health. One of my main responsibilities over the past year has been to work with the heads of all the entities in the UN system as they work together for the Sustainable Development Goals and act on climate change. As Director-General, I will build on these relationships and seek to increase the extent to which the entire UN system focuses on people's health.

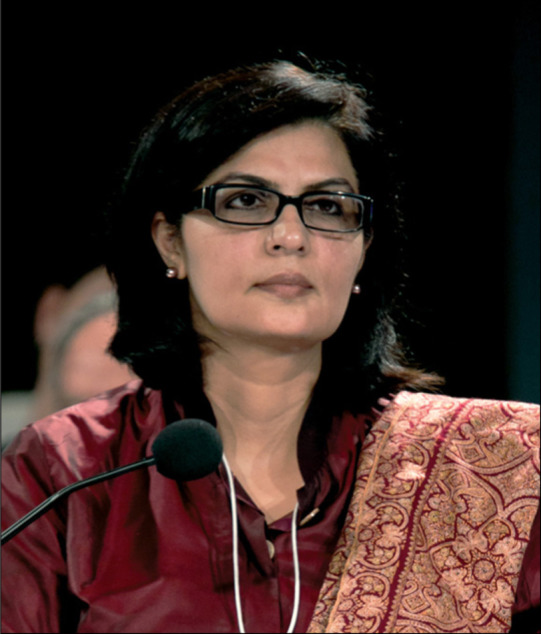

Sania Nishtar

Pakistan

© 2016 Benedikt von Loebell

As WHO nears its 70th anniversary, the mood is not yet celebratory. While some Member States still express support for and confidence in the organisation, others openly debate WHO's merits and consider the case for its continued survival. In a world brimming with unprecedented opportunity for health improvement, WHO faces structural limitations and reputational damage. The new Director-General must usher in an era of renewal.

Against this backdrop, I present my vision, centred on the firm belief that as the world's only universal multilateral agency in health, WHO has critical mandates and that its relevance matters deeply today in the face of several pressing health challenges, and my conviction that the organisation has the potential to re-emerge as the world's most trusted and leading health agency. My vision, therefore, focuses first on the need for WHO to reclaim its primacy and earn the world's trust as its lead health agency. Such renewal will not simply be a matter of reorganisation; it must run deeper and touch every aspect of the life of WHO. I pledge, therefore, to bring reforms to rapid fruition, to embrace meaningful and timely transparency, to institutionalise true accountability, to ensure value for money, and to drive a culture based on results and concrete delivery. These have featured saliently in my 10 Pledges, to achieve a renewed and reinvigorated WHO.