Summary

Annually, millions of Muslims embark on a religious pilgrimage called the “Hajj” to Mecca in Saudi Arabia. The mass migration during the Hajj is unparalleled in scale, and pilgrims face numerous health hazards. The extreme congestion of people and vehicles during this time amplifies health risks, such as those from infectious diseases, that vary each year. Since the Hajj is dictated by the lunar calendar, which is shorter than the Gregorian calendar, it presents public-health policy planners with a moving target, demanding constant preparedness. We review the communicable and non-communicable hazards that pilgrims face. With the rise in global travel, preventing disease transmission has become paramount to avoid the spread of infectious diseases, including SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome), avian influenza, and haemorrhagic fever. We examine the response of clinicians, the Saudi Ministry of Health, and Hajj authorities to these unique problems, and list health recommendations for prospective pilgrims.

Introduction

Hajj is the pilgrimage to Mecca and related holy sites. According to Islam, every physically able muslim must undertake the Hajj once in his lifetime. During Hajj, millions of Muslims retrace the footsteps of the Prophet Mohammed, undertaking identical rituals.

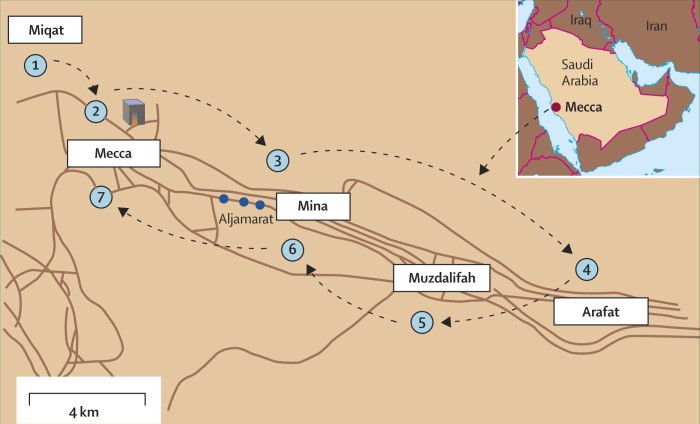

Hajj is performed in the 12th month of the Islamic (lunar) calendar. On arrival at Mecca, each pilgrim, makes seven circumambulations (Tawaf) around the Ka'aba (the building muslims consider the house of God). He then leaves for the Plain of Arafat, a few miles east of Mecca, where the Hajj culminates in the “Day of Standing”. The pilgrim makes overnight stops in Mina en route to Arafat, and in Muzdaliffah on return (figure 1 ). On returning to Mina, the pilgrim stops at Jamarat to stone the pillars that are effigies of Satan. The new Hajjee (a pilgrim who has completed the Hajj) then makes an animal sacrifice (usually by proxy) as thanks for an accepted Hajj. After a farewell Tawaf, the pilgrim leaves Mecca.

Figure 1.

The Hajj Journey

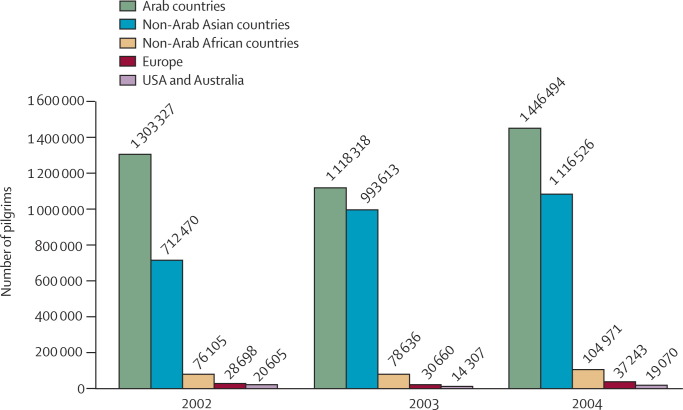

Mecca is also the setting for a smaller ritual called Umrah, performed year-round. Improved international travel renders Umrah also very congested, especially in the three months preceding the Hajj (figure 2 ). Many pilgrims also travel to Medina, north of Mecca, where the Prophet Mohammed is buried. Although the Medina visit is a non-essential part of the Hajj, millions complete this ritual.

Figure 2.

Numbers of pilgrims arriving from abroad for Umrah: 2002–04

This mass migration (figure 3 ) entails some of the world's most important public-health and infection-control problems.1 Although distances are small, the congestion of the Hajj (figure 4 ) poses high physical, environmental, and health-care demands. Not only that, the Hajj is marked on a lunar calendar, which is 10 days shorter than the Gregorian one. This continuous seasonal movement has implications for the spread of disease and other health risks, challenging public-health policy planners further. The severe congestion of people means that emerging infectious diseases have the potential to quickly turn into epidemics. With each Hajj, authorities refine the management of Hajj health procedures.2, 3, 4, 5, 6

Figure 3.

Numbers of pilgrims arriving for the Hajj from abroad: 2005

Figure 4.

Crowds at the Hajj

Extended stays at Hajj sites, extreme heat, and crowded accommodation encourage disease transmission, especially of airborne agents. Traffic jams, and inadequately prepared or stored food are added health risks. The advanced age of many pilgrims adds to the morbidity and mortality risks. Preparation is essential: the Neisseria meningitidis W135 outbreak in 2000–01 was an example of the epidemiological “amplifying chamber” that Hajj becomes.

Communicable diseases

Meningococcal disease

The congestion of people during the Hajj promotes increased carrier rates of N meningitidis. Carrier rates of 80% have been reported in congested sections of Mecca.7 In 1987, after a large outbreak of meningococcal disease serogroup A in pilgrims, Saudi Arabian health authorities implemented three preventive strategies: (1) compulsory vaccination with bivalent A and C vaccine for all pilgrims; (2) annual vaccination campaigns for all living in high-risk areas (pilgrimage sites) or among high-risk groups; (3) compulsory oral ciprofloxacin to pilgrims from sub-Saharan Africa.2, 8, 9 By February 1999, with no evidence of ongoing epidemic meningococcal disease in Saudi Arabia, the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) lifted these requirements.10, 11 But in the subsequent Hajj seasons of 2000 and 2001, outbreaks of the disease affected 1300 and 1109 people, respectively. More than 50% of these cases were confirmed to be of N meningitides serogroup W135.2, 12

The rapidly changing pattern of meningococcal disease prompted the Saudi ministry of health to make recommendations (in 2001, in preparation for the 2002 Hajj season) for the prevention of meningococcal disease and other communicable diseases (table ).4, 6 All pilgrims and local at-risk populations must now be given the quadrivalent polysaccharide vaccine—Hajj visas cannot be issued without proof of vaccination.4 Concerns over the immunogenicity of the vaccine in children younger than 5 years, the lack of effect on carrier status, and the need for booster doses after 3 years limit the efficacy of existing preparations.13, 14, 15, 16 A conjugated quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine (Menactra) was only licensed recently in the USA in January, 2005, and should be more widely available by 2007. Because it elicits a T-cell dependent immune response it is expected to offer immunity for more than 8 years, and eliminate the threat of the disease in all ages during the Hajj because it prevents transmission of infection from person to person.17, 18

Table.

Preventive measures for Hajj-associated health risks

| Recommendations | |

|---|---|

| Before the Hajj | |

| General measures | Routine physical examination |

| Renew medications | |

| Carry a thermometer | |

| Carry a 3-day course of ciprofloxacin | |

| Carry loperamide | |

| Vaccinations | Polysaccharide quadrivalent meningococcal vaccine (>2 years of age)* |

| Polysaccharide monovalent A meningococcal vaccine (<2 years of age)* | |

| Influenza vaccine* | |

| Pneumococcal vaccine (age >65 years) | |

| HAV (all ages) for patients from developed countries with negative IgG for HAV | |

| HBV (all ages) | |

| Polio oral vaccination is given to all children <15 years from selected African and Asian countries*. | |

| Yellow fever vaccine for pilgrims from endemic areas* | |

| Other | Consider two-step purified protein dervative testing or |

| QuantiFERON tuberculosis assay for pilgrims from countries with low tuberculosis endemicity | |

| Consider pertussis acellular vaccine | |

| During the Hajj | |

| Facemask use* | |

| Adequate hydration | |

| Sunscreen | |

| Seek shade | |

| Perform rituals at night if possible | |

| Avoid severe crowds | |

| Hand hygiene | |

| Initiate self treatment as needed | |

| Continue usual medications | |

| After the Hajj | |

| Medical follow-up | |

| Early medical help | |

| Consider follow-up purified protein dervative testing or | |

| QuantiFERON for pilgrims from countries with low tuberculosis endemicity | |

Saudi ministry of health recommendations.

Respiratory tract infections

Researchers undertaking a prospective study in two hospitals during the Hajj identified respiratory disease as the most common cause (57%) of admission to hospital, with pneumonia being the leading reason for admission in 39% of all patients.19 Researchers investigating the pathogens causing respiratory tract infections during the Hajj, obtained 395 sputum samples from patients presenting with such disease.20 They recorded Haemophilus influenza, Klebsiella pneumoniae, and Streptococcus pneumoniae as the most common pathogens. Bacterial cultures were positive in 30% of all individuals sampled. The Advisory Committee on Immunization Practices recommends pneumococcal vaccination for all those older than 65 years, and for those younger than 65 years with co-morbidities.21

In a study of pathogens of community-acquired pneumonia during the 1994 Hajj,22 bacteriological diagnosis was confirmed in 46 (72%) patients. Mycobacterium tuberculosis was the most common pathogen identified (13 [20%] patients). If validated, this study could have important implications for diagnosis, treatment, and infection control of pneumonia at the Hajj. Until then, physicians should keep a high index of suspicion for tuberculosis in patients presenting with community-acquired pneumonia during the Hajj. The immune response to tuberculosis antigens with a whole blood assay (QuantiFERON TB assay) has been measured in Singaporean pilgrims before, and 3 months after the Hajj.23 Of 357-paired assays, 149 pilgrims had negative tests before the Hajj. But 15 (10%) of these had a substantial rise in immune response to the antigens during the Hajj. This rise indicates that pilgrims from low tuberculosis-endemicity should be screened with a two-step purified protein derivative or QuantiFERON-TB before the Hajj and 3 months after, to detect new conversions.24, 25, 26, 27 The prevalence of resistant tuberculosis is up to three times greater in Mecca and Medina than Saudi national averages.28, 29 This difference is due to the annual influx of pilgrims from areas of high tuberculosis-endemicity.30

The bulk of pilgrims now enter the region by air, often after long airplane journeys.31, 32 Despite several documented cases of tuberculosis acquired during air travel, the risk of such transmission remains low.33, 34 Specific data pertaining to Hajj travel do not exist.

Viral respiratory tract infections, particularly influenza, are common during the Hajj.20, 35, 36 Throat swabs from 761 patients with upper respiratory tract infections were positive for viral pathogens in 152 (20%), with influenza A and adenovirus being the most common.20 In another study,35 500 pilgrims with upper respiratory tract infection symptoms were screened by throat swabs for viral culture. 54 (10·8%) had positive cultures. Of these, 27 (50%) had influenza B, 13 (24·1%) had herpes simplex virus, seven (12·9%) had respiratory syncytial virus, four (7·4%) had parainfluenza, and three (5·6%) had influenza A. No enteroviruses or adenoviruses were detected, and no multiple infections were detected. Only 22 (4·7%) had received the influenza vaccine. When extrapolating their results to the total number of pilgrims in 2003, the researchers estimated there were 400 000 pilgrims with respiratory symptoms and 24 000 possible cases of influenza in that Hajj.

The benefit of influenza vaccination was assessed in an unmatched case-control study on pilgrims of the 2000 Hajj.37 In 820 patients and 600 controls, the adjusted vaccine efficacy against clinic visits for influenza-like illness was 77% (95% CI 69–83), and that against receipt of antibiotics was 66% (54–75). The Saudi ministry of health recommends influenza vaccination to pilgrims, especially those with underlying comorbidities (table), and the vaccine is mandatory for all healthcare workers working in Mecca and Medina.

The ministry also recommends the use of facemasks during the Hajj, to reduce the airborne transmission of disease. Compliance with this recommendation has been poor: during the 1999 Hajj, only 24% of pilgrims wore face masks.38 Although there are few data for the effectiveness of facemask use in prevention of respiratory tract infections at the Hajj, it is a simple and inexpensive infection control measure.

Pertussis is another respiratory tract infection of concern. A prospective seroepidemiological study determined the incidence of pertussis in 358 adult pilgrims.39 Five (1·4%) had acquired pertussis (defined as prolonged cough and a greater than four-fold increase in the level of immunoglobulin G to whole-cell pertussis antigen). Of the 40 pilgrims who had no pre-Hajj immunity to pertussis, three (7·5%) acquired pertussis. The investigators suggested the administration of acellular pertussis vaccine to pilgrims. Results of further large-scale studies will be needed before making the vaccine a general recommendation to all pilgrims.

Diarrhoeal disease

Traveller's diarrhoea is common during the Hajj, although few studies have documented its incidence and aetiology. In the 1986 Hajj, the most common cause of hospital admissions for pilgrims was gastroenteritis (n=381, 76·6%) with an incidence rate of 4·4 per 10 000. 41% (156) of these patients were older than 60 years.40 In a 2002 study, gastrointestinal disease ranked third (n=10, 6·3%) after respiratory system (n=91, 57%) and cardiovascular disease (n=31, 19·4%) as reasons for admission.19

Cholera, an acute bacterial enteric disease caused by Vibrio cholera accounted for several outbreaks after the Hajj in 1984–86.41, 42 According to the Saudi ministry of health, cholera has reached Hajj areas and caused epidemics recorded as far back as 1846. The last epidemic at the Hajj in 1989 affected 102 pilgrims (Saudi ministry of health, personal communication). Improved water supply and sewage systems have eliminated cholera outbreaks since then. However, sporadic cases of cholera have still been diagnosed in Saudi Arabia.43, 44

Hepatitis A is also common in Saudi Arabia,45, 46 and is the most frequent vaccine-preventable illness contracted by travellers. It is probably common during the Hajj, but, there are no data for this.

Food poisoning is another important cause of diarrhoea and vomiting during the Hajj.47 During the past 12 years, the number of reported cases of food poisoning has ranged from 44 to 132 in each Hajj season.

Prevention of diarrhoeal diseases includes education of the pilgrims regarding hand hygiene, avoidance of street vendor food (including ice), and avoidance of foods made with fresh eggs. Authorities do not allow pilgrims to carry food, except for canned food sufficient for 24 hours.6 The ministry of health mandates the surveillance of pilgrims arriving from cholera-affected countries (identified in weekly WHO reports). If suspected, samples are taken and those infected are quarantined. Contacts are also tested.6 Hepatitis A virus vaccine is recommended for pilgrims from developed countries—it is probably unnecessary for those from developing countries since they are likely to be immune because of childhood exposure. Travellers can be checked for hepatitis A virus immunoglobulin G (IgG) before administration of the vaccine, to avoid needless vaccination.48

Pilgrims must be educated about self-treatment of diarrhoeal disease. Adequate rehydration is vital. Self-administered antibiotics with an extended spectrum macrolide, azithromycin, or oral quinolone are probably indicated for moderate to severe travellers' diarrhoea (table).49, 50

Skin infections

Lengthy rituals of standing and walking, chafing garments, heat and diaphoresis all promote skin infection at the Hajj, and bacterial skin infections have been well described in Hajj pilgrims. One study included 1441 patients at an outpatient dermatology clinic in Mecca during two Hajj seasons.51, 52 Primary pyoderma (including impetigo), carbuncles, furuncles, and folliculitis were commonly seen. Secondary pyoderma complicated eczema. Other conditions included cutaneous leishmaniasis in two patients.

Pilgrims are barefoot in some holy areas. Standing on scorching marble in the midday sun can severely burn the soles of the feet.53, 54 New marble surfaces that do not absorb heat to the same degree have now been installed at the mosque. Pilgrims should keep their skin dry and use talcum powder to keep intertriginous areas intact. They must be vigilant of pain or soreness caused by garments. Exposed skin should be protected. Any pre-existing skin condition should be protected and medicated as appropriate and the pilgrim must travel with their usual medications and ointments, which are all permissible during the Hajj.

Orf is a viral disease of sheep and goats, caused by the parapox virus. Seasonal orf has been reported in abattoir workers. Human infection results from direct contact with infected animals, producing skin lesions. 13 cases of orf hand infection acquired by slaughtering sheep at the Hajj have been reported.55 Since few pilgrims perform the sacrifice themselves, the risk of infection is small.

Blood-borne diseases

Muslim men complete the Hajj by shaving their heads. Shaving can facilitate the transmission of blood-borne disease, including hepatitis B and C, and HIV.56 Official regulations mandate both testing of barbers for hepatitis B (HBV) and C (HCV), and HIV, and the use of disposable single-use blades.57 Unlicensed barbers operating at the Hajj, shave hair at the roadside with non-sterile blades that are re-used on several people. Data from 1999 for hepatitis serology in 158 Hajj barbers showed that seven (4%) were positive for HBsAg (hepatitis B surface antigen), 16 (10%) were HCV-positive, and one (0·6%) was positive for HbeAg (hepatitis B “e” antigen), indicating high infectivity.58 Saudi authorities continue to take an aggressive legislative stance to prevent unlicensed barbers from operating during the Hajj. All pilgrims need to be aware of these hazards and must be shaved only at designated centres. Since there are no published data to document the significance of head shaving in HBV transmission to pilgrims, and since the HBV vaccine series takes 6 months to complete, it is difficult to recommend the HBV vaccine to all pilgrims. Individuals who are counselled in sufficient time before the Hajj, and who can afford the vaccine cost, should take the HBV vaccine.

Emerging infectious diseases

Emerging infectious diseases—such as viral haemorrhagic fever (VHF) syndromes—are a special concern in Hajj health care. Rift Valley fever is a VHF that affects mainly livestock but also humans.59, 60, 61, 62, 63 Reports in September, 2000, first documented cases of the fever outside of Africa, in Saudi Arabia and Yemen.63, 64 This epidemic was of major concern for the Hajj.65 The ministries of health and of agriculture collaborated to restrict the entry of sheep to the holy sites from regions in Saudi Arabia endemic with the virus, and by launching an educational program for Mecca abattoir workers. No outbreaks of Rift Valley fever at the Hajj have yet been reported. Another new VHF caused by a flavivirus was isolated in 1995 from six patients from south of Jeddah.66 The pathogen has been identified as Alkhumra virus.67, 68 During the Hajj 2001, four cases were diagnosed in Mecca.69 So far, there have been 37 cases. Ebola virus is another cause of VHF that has caused several outbreaks in Africa. Saudi Arabia banned all Ugandan residents from attending the Hajj 2001 because of the concern over Ebola, which has killed more than 170 Ugandans.70, 71 This ban was lifted by the end of 2001 Hajj season.

Briefly in 2003, SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) presented a potentially enormous threat to Hajj pilgrims, particularly because the virus' spread could be facilitated by air travel.72, 73 The conditions of the Hajj could turn a single case of SARS into an epidemic of unprecedented scale. Saudi authorities implemented several strategies to prevent the entry of SARS, including delayed entry for pilgrims from countries reporting local SARS transmission: people from these countries would not be allowed to enter Saudi Arabia until 10 days had elapsed since they left their own country.74, 75 Thermal cameras in the Damam, Jeddah, and Riyadh international airports can now detect febrile patients. Laboratories are now equipped with PCR kits for identifying the SARS virus genome and immunofluorescence assays to detect antibodies to the SARS virus. In 2003, the ministry of health launched an educational campaign about infection control strategies for health-care personnel who might encounter SARS patients. So far, no cases of SARS have been reported in Saudi Arabia,76 and authorities do not believe that the virus presents any further concerns to the Hajj.

Avian influenza (H5N1) is of major global concern.77, 78, 79 The WHO reported 175 confirmed human cases of avian influenza A (H5N1) as of Mar 6, 2006, of whom 95 died. Although this number is low, this frequently mutating, highly virulent virus is a major threat to Hajj pilgrims. The Saudi Authorities have already restricted bird importation in order to prevent avian influenza entering the country. At present no vaccine exists.80

In November, 2004, a Sudanese child was diagnosed with polio one day after arrival in Saudi Arabia.6, 81 This case coincided with the diagnosis of another 104 cases in Sudan.81 In response, the Saudi ministry of health now stipulates that all visitors under the age of 15 years from countries reporting cases of polio will be required to show proof of vaccination to obtain visas for entry to Saudi Arabia. In addition, irrespective of previous immunisation status, polio vaccination at Saudi Arabian borders for people younger than 15 years arriving from those countries will be mandatory.4, 6 Although some believe that polio spreads to other countries by returning pilgrims, there is no evidence to support this belief.

Non-communicable diseases

Cardiovascular diseases

Cardiovascular disease is the most common cause (43%) of death during the Hajj.82 Many patients have cardiac arrests, outside hospitals, at Hajj sites. Although health-care response workers are ambulance-supported emergency medical service teams, pilgrims can rarely be resuscitated. Retrieving patients in “peri-arrest” from massive crowds is difficult, and can itself pose danger to others.

Hajj is arduous even for healthy adults—for those with pre-existing cardiac disease, the physical stress can easily precipitate ischaemia. The onus is on the pilgrim to avoid the Hajj if their cardiac status is precarious, and clinicians must encourage this preventative stance. Cardiac patients planning for the Hajj should consult with their doctors before the journey; ensure sufficient supply of, and compliance with, medications. They should avoid crowds, perform some rituals by proxy, and report to the closest health centre for any symptom indicating cardiac decompensation.

Trauma risks

Trauma is a major cause of morbidity and mortality at the Hajj. In a prospective study on 713 trauma patients, who were injured while performing Hajj, presenting to the emergency room, 248 (35%) were admitted to surgical departments and intensive care.83 The most common surgical presentations were orthopedic and neurosurgical.83 Trauma risks are not confined to holy sites themselves.84, 85 For a large part of the Hajj, pilgrims travel either by foot, walking through or near dense traffic, or in vehicles themselves. Extreme traffic build-up, poor compliance with seatbelts, and disordered traffic flow contributes to trauma risk. Motor vehicle accidents are inevitable, and contribute to casualties and deaths during the Hajj. The national database compiled by the Saudi National Committee for Traffic Safety recorded 267 772 motor vehicle accidents in Saudi Arabia, of which 4848 were fatalities. The highest incidence of accidents—94 699—was recorded in Mecca province indicating a very high risk of motor vehicle accidents in view of Mecca's relatively small size.

Stampede is perhaps the most feared trauma hazard. Once started, little can be done to stop panic spreading through crowds, contributing to casualties, and all too often, fatalities.86 At the Hajj 2006, stampedes followed pilgrims tripping over fallen luggage, and resulted in 380 deaths and 289 wounded (panel ). Fatalities result from asphyxiation or head injury, neither of which can be attended to quickly in large crowds.

Panel. Chronicle of Hajj disasters.

1990: 1426 pilgrims killed by stampede/asphyxiation in tunnel leading to holy sites

1994: 270 killed in a stampede

1997: 343 pilgrims died and 1500 injured in a fire

1998: 119 pilgrims died in a stampede

2001: 35 pilgrims died in a stampede

2003: 14 pilgrims died in a stampede

2004: 251 pilgrims died in a stampede

2006: 76 pilgrims died after a hotel housing pilgrims collapsed; a stampede wounded 289, killing 380

No major disasters recorded in years not listed.

Particularly dangerous for stampedes is the Jamarat area, where crowds surge around the pillars.2 To reduce this crowding, the cylindrical columns have been replaced with elliptical ones, increasing the surface area available for stoning and dissipating intense crowd pressure surrounding each column. After the Hajj 2006 in January, work started on a new Jamarat project. A 4-level Jamarat bridge will be built at an estimated cost of $1·1 billion with a capacity of 5 million pilgrims over 6 hours. The 12 entrances and 13 exits will be supported with helipads, electronic surveillance, and shading and cooling mists. 80% of this new project will be ready for 2007 Hajj season.

The panel lists Hajj-related disasters. Each disaster results in policy change, and a redoubling of efforts—which have so far cost more than $25 billion to prevent future incidents.87

Fire-related injury

In 1997, fire devastated the Mina area when makeshift tents were set ablaze by open stoves, since banned at the Hajj. There were 343 deaths and more than 1500 estimated casualties.88 Since then all makeshift tents have been replaced by permanent fibreglass installations. At Hajj time, teflon-coated awnings are added, and the aluminum frames remain in place the rest of the year. No pilgrim is permitted to set up his own tent. Additionally, pilgrims are not allowed to cook food at Mina. Smoking is forbidden during the Hajj by Islamic teaching, thus reducing the risk of a naked flame. Continuous public education is being undertaken to further reduce fire risk.

Environmental heat injury

Heat exhaustion and heatstroke is a leading cause of morbidity and mortality during the Hajj, particularly in summer.89, 90 Temperatures in Mecca can rise higher than 45°C. Lack of acclimatisation, arduous physical rituals, and exposed spaces with limited or no shade, produces heatstroke in many pilgrims. Adequate fluid intake and seeking shade is essential. Supplicating pilgrims might not notice the dangers of extreme heat exposure until their symptoms are pronounced. Water mist sprayers operate regularly in the desert at Arafat, a time of high risk for heatstroke, when many stand for long hours during the day. Performing rituals at night, using umbrellas, seeking shade, and wearing high-SPF sunblock creams are all advisable and permissible during the Hajj. Children accompanying their parents must be especially protected. The timings of rites are flexible and acceptable at the pilgrim's convenience—it is key that pilgrims are aware of this since, through fear of committing errors, they might not make sensible choices in completing their rituals.

For the management of heatstroke, hospitals are equipped with special cooling units.91 Although the Hajj is not due to fall in the summer for several years, Saudi winters are warmer (25–30°C) than most pilgrims will be used to, and they must seek shade and drink plenty of fluid during their rites.

Occupational hazards of abattoir workers

Abattoir workers at the Hajj are exposed to unique traumatic risks. Over a million cattle are slaughtered each Hajj, up to half a million before noon on the 10th day of the Hajj.92 In one study, 298 emergency visits for hand injury were treated in Mecca over four Hajj seasons.93 More than 80% were injuries from animal slaughter; many avoidable injuries were sustained by lay people and not trained abattoir workers. Pilgrims need to be assured that professional slaughtering arrangements are easily available at the Hajj, and far safer.2

The future of the Hajj

The numbers of people undertaking the Hajj continue to grow, in spite of the past 4 years of regional turmoil. Overall, the Hajj remains surprisingly peaceful and organised, in view of its colossal scale.

But travellers to Mecca face specific environmental hazards, both through the physical environment, and through the unique microbiological setting created there during the Hajj. Years ago, the pilgrimage itself was arduous, and many died on the way. Now, however, the Hajj itself presents risks which, unanticipated, can lead to disease and death. Additionally, the potential for disease to spread is greater in our time of global travel.

Clinicians must be aware of risks and strategies to tackle them, many of which are simple measures, and can be undertaken both before departure and in the field. Doctors must also be aware of the risks posed by returned pilgrims, and be alert to reporting any post-Hajj illness.

Hajj management, even for a nation as well-resourced as Saudi Arabia, is an overwhelming task. International collaboration by planning vaccination campaigns, developing visa quotas, and arranging rapid repatriation are integral to managing health hazards at the Hajj.

Search strategy and selection criteria

We searched MEDLINE for the search terms “Hajj”, “pilgrimage”, “Makkah”, or “Mecca” between 1966 and 2006, concentrating on the latest publications. Some older publications were obtained from British Library archives in London, UK. We used the reference lists of articles identified by this strategy as further sources. Finally, we accessed official Saudi governmental statistics, with a particular emphasis on data from the Saudi Ministry of Health. Our search was restricted to papers published in English and Arabic.

Conflict of interest statement

We declare that we have no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.Memish ZA. Infection control in Saudi Arabia: meeting the challenge. Am J Infect Control. 2002;30:57–65. doi: 10.1067/mic.2002.120905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Memish ZA, Venkatesh S, Ahmed QA. Travel epidemiology: the Saudi perspective. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;21:96–101. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(02)00364-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gatrad AR, Sheikh A. Hajj: journey of a lifetime. BMJ. 2005;330:133–137. doi: 10.1136/bmj.330.7483.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Health conditions for travellers to Saudi Arabia pilgrimage to Mecca (Hajj) Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2005;80:431–432. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Risk for meningococcal disease associated with the Hajj 2001. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2001;50:97–98. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Shafi S, Memish ZA, Gatrad AR, Sheikh A. Hajj 2006: communicable diseases and other health risks and current official guidance for pilgrims: Eurosurveillance Weekly, 2005; 10. http://www.eurosurveillance.org/ew/2005/051215.asp (accessed March 10, 2006) [DOI] [PubMed]

- 7.Al-Gahtani YM, El bushra HE, Al-Qarawai SM, Al-Zubaidi AA, Fontaine RE. Epidemiolological investigation of an outbreak of meningococcal meningitis in makkah (Mecca), Saudi Arabia, 1992. Epidemiol Infect. 1995;115:399–409. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800058556. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wilder-Smith A, Memish ZA. Meningococcal disease and travel. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;21:102–106. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(02)00284-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Memish ZA. Meningococcal disease and travel. Clin Infect Dis. 2002;34:84–90. doi: 10.1086/323403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Change in recommendation for meningococcal vaccine for travelers. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 1999;48:104. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.From the Centers for Diseases Control and prevention Change in recommendation for meningococcal vaccine for traveler. JAMA. 1999;281:892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Al-Mazrou YY, Al-Jeffri MH, Abdalla MN, Elgizouli SA, Mishskas AA. Changes in epidemiological pattern of Meningococcal disease in Saudi Arabia. Does it constitute a new challenge for prevention and control? Saudi Med J. 2004;25:1410–1413. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Balkhy HH, Memish ZA, Osoba AO. Meningococcal carriage among local inhabitants during the pilgrimage 2000–2001. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;21:107–111. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(02)00356-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Al-Mazrou Y, Khalil M, Borrow R. Serologic response to ACYW135 polysacharide meningococcal vaccine in Saudi children under 5 years of age. Infection and Immunity. 2005;73:2932–2939. doi: 10.1128/IAI.73.5.2932-2939.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khalil M, Al-Mazrou Y, Balmer P, Bramwell J, Andrews N, Borrow R. Immunogenicity of meningococcal ACYW135 polysacharide vaccine in saudi children 5 to 9 years of age. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2005;12:1251–1253. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.12.10.1251-1253.2005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jokhdar H, Borrow R, Sultan A. Immunologic hyporesponsiveness to serogroup C but not serogroup A following repeated meningococcal A/C polysacharide vaccination in Saudi Arabia. Clin Diagn Lab Immunol. 2004;11:83–88. doi: 10.1128/CDLI.11.1.83-88.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Menactra: a meningococcal conjugate vaccine. Med Lett Drugs Ther. 2005;47:29–31. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Harrison LH. Prospects for vaccine prevention of meninigococcal infection. Clin Microbiol Rev. 2006;19:142–164. doi: 10.1128/CMR.19.1.142-164.2006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Al-Ghamdi SM, Akbar HO, Qari YA, Fathaldin OA, Al-Rashed RS. Pattern of admission to hospitals during muslim pilgrimage (Hajj) Saudi Med J. 2003;24:1073–1076. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.El-Sheikh SM, El-Assouli SM, Mohammed KA, Albar M. Bacteria and viruses that causes respiratory tract infections during the pilgrimage (Haj) season in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Trop Med Int Health. 1998;3:205–209. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Whitney CG. Preventing pneumococcal disease. ACIP recommends pneumococcal polysacharide vaccine for all adults age ⩾65. Geriatrics. 2003;58:20–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Alzeer A, Mashlah A, Fakim N. Tuberculosis is the commonest cause of pneumonia requiring hospitalization during hajj (pilgrimage to Makkah) J Infect. 1998;36:303–306. doi: 10.1016/s0163-4453(98)94315-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wilder-Smith A, Foo W, Earnest A, Paton NI. High risk of Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection during the Hajj pilgrimage. Trop Med Int Health. 2005;10:336–339. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-3156.2005.01395.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al-Jahdali H, Memish ZA, Menzies D. Tuberculosis in association with travel. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;21:125–130. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(02)00283-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Al-Jahdali H, Memish Z, Menzies D. The utility and interpretation of tuberculin skin test in the Middle East. Am J Infect Control. 2005;33:151–156. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2005.01.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johnston VJ, Grant DG. Tuberculosis in travellers. Travel Med Infect Dis. 2003;1:205–212. doi: 10.1016/j.tmaid.2003.11.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mazurek GH, Jereb J, Lobue P, Iademarco MF, Mertchok B, Vernon A. Guidelines for using the QuantiFERON-TB Gold test for detecting Mycobacterium tuberculosis infection, United States. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2005;54:49–55. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Khan MY, Kinsara AJ, Osoba AO, Wali S, Samman Y, Memish Z. Increasing resistance of M tuberculosis to anti-TB drugs in Saudi Arabia. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2001;17:415–418. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(01)00298-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Al-Kassimi FA, Abdullah AK, Al-Hajjaj MS, Al-Orainey IO, Bamgboye EA, Chowdhury MN. Nationwide community survey of Tuberculosis epidemiology in Saudi Arabia. Tuber Lung Dis. 1993;74:254–260. doi: 10.1016/0962-8479(93)90051-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Memish ZA, Ahmed QA. Mecca bound: the challenges ahead. J Travel Med. 2002;9:202–210. doi: 10.2310/7060.2002.24557. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Driver CR, Valway SE, Morgan WM, Onorato IM, Castro KG. Transmission of Mycobacterium tuberculosis associated with air travel. Jama. 1994;272:1031–1035. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Ormerod P. Tuberculosis and travel. Hosp Med. 2000;61:171–173. doi: 10.12968/hosp.2000.61.3.1294. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Kenyon T, Valway SE, Ihle WW, Onorato IM, Castro KG. Transmission of multi-drug resistant Mycobacterium tuberculosis during long airplane flight. N Engl J Med. 1996;334:933–938. doi: 10.1056/NEJM199604113341501. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McFarland JW, Hickman C, Osterholm M, MacDonald KL. Exposure to Mycobacterium tuberculosis during air travel. Lancet. 1993;342:112–113. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Balkhy HH, Memish ZA, Bafaqeer S, Almuneef MA. Influenza a common viral infection among Hajj pilgrims: time for routine surveillance and vaccination. J Travel Med. 2004;11:82–86. doi: 10.2310/7060.2004.17027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Freedman DO, Leder K. Influenza: changing approaches to prevention and treatment in travelers. J Travel Med. 2005;12:36–44. doi: 10.2310/7060.2005.00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Mustafa AN, Gessner BD, Ismail R. A case-control study of influenza vaccine effectiveness among Malaysian pilgrims attending the Hajj in Saudi Arabia. Int J Infect Dis. 2003;7:210–214. doi: 10.1016/s1201-9712(03)90054-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Al-Shehry AM, Al-Khan AA. Pre-Hajj health related advice, Makkah. Saudi Epidemiol Bull. 1999;6:29–31. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Wilder-Smith A, Earnest A, Ravindran S, Paton NI. High incidence of pertussis among Hajj pilgrims. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;37:1270–1272. doi: 10.1086/378748. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Ghaznawi HI, Khalil MH. Health hazards and risk factors in the 1406 (1986) Hajj season. Saudi Med J. 1989;9:274–282. [Google Scholar]

- 41.Onishchenko GG, Lomov Iu M, Moskvitina EA. [Cholera in the Republic of Dagestan] Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol. 1995;(suppl 2):3–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Onishchenko GG, Lomov Iu M, Moskvitina EA. [The epidemiological characteristics of cholera in the Republic of Dagestan. An assessment of the epidemic-control measures] Zh Mikrobiol Epidemiol Immunobiol. 1995;(suppl 2):9–22. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Eltahawy AT, Jiman-Fatani AA, Al-Alawi MM. A fatal non-01 Vibrio cholerae septicemia in a patient with liver cirrhosis. Saudi Med J. 2004;25:1730–1731. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bubshait SA, Al-Turki K, Qadri MH, Fontaine RE, Cameron D. Seasonal, nontotoxogenic Vibrio cholera 01 Ogawa infections in the Eastern region of Saudi Arabia. Int J Infect Dis. 2000;4:198–202. doi: 10.1016/s1201-9712(00)90109-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Tufenkeji H. Hepatitis A shifting epidemiology in the Middle East and Africa. Vaccine. 2000;18(suppl 1):565–567. doi: 10.1016/s0264-410x(99)00468-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Memish Z, Qasim L, Abed E. Pattern of viral hepatitis infection in a selected population from Saudi Arabia. Mil Med. 2003;168:565–568. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Al-Mazrou YY. Food poisoning in Saudi Arabia. Potential for prevention? Saudi Med J. 2004;25:11–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Memish ZA, Oni GA, Bannatyne RM, Qasem L. The cost-saving potential of prevaccination antibody tests when impleminting mass immunization program. Mil Med. 2001;166:11–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Al-Abri SS, Beeching NJ, Nye FJ. Travellers diarrhea. Lancet Infect Dis. 2005;5:349–360. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(05)70139-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Ericsson C. Travellers diarrhea. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;21:116–124. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(02)00282-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Fatani MI, Bukhari SZ, Al-Afif KA, Karima TM, Abdulghani MR, Al-Kaltham MI. Pyoderma among Hajj Pilgrims in Makkah. Saudi Med J. 2002;23:782–785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Fatani MI, Al-Afif KA, Hussain H. Pattern of skin diseases among pilgrims during Hajj season in Makkah, Saudi Arabia. Int J Dermatol. 2000;39:493–496. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-4362.2000.00009.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Al-Qattan MM. The ‘Friday mass’ burns of the feet in Saudi Arabia. Burns. 2000;26:102–105. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(99)00097-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Fried M, Kahanovitz S, Dagan R. Full thickness feet burn of a pilgrim to Mecca. Burns. 1996;22:644–645. doi: 10.1016/s0305-4179(96)00048-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hawary MB, Hassanain JM, Al-Rasheed SK. Al-Qattan MM The yearly outbreak of Orf infection of the hand in Saudi Arabia. J Hand Surgery. 1997;4:550–551. [Google Scholar]

- 56.Gatrad AR, Sheikh A. Hajj and risk of blood borne infections. Arch Dis Child. 2001;84:375. doi: 10.1136/adc.84.4.373h. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Al-Salama AA, El-Bushra HE. Head shaving practices of barbers and pilgrims to Makkah. Saudi Epidemiol Bull. 1998;5:3–4. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Turkistani A, Al-Rumikhan A, Mustafa T. Blood-borne diseases among barbers during Hajj 1999. Saudi Epidemiol Bull. 2000;7:1–2. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Flick R, Bouloy M. Rift valley fever virus. Curr Mol Med. 2005;5:827–834. doi: 10.2174/156652405774962263. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Al-Hazmi M, Ayoola EA, Abdulrahman M. Epidemic Rift valley fever in Saudi Arabia: a clinical study of severe illness in humans. Clin Infect Dis. 2003;36:245–252. doi: 10.1086/345671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Balkhy HH, Memish ZA. Rift Valley Fever: an uninvited zoonosis in the Arabian peninsula. Int J Antimicrob Agents. 2003;21:153–157. doi: 10.1016/s0924-8579(02)00295-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Jup PG, Kemp A, Grobbelaar A. The 2000 epidemic of Rift valley fever in Saudi Arabia: mosquito vector studies. Med Vet Entomol. 2002;16:245–252. doi: 10.1046/j.1365-2915.2002.00371.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Update : outbreak of Rift valley fever in Saudi Arabia. JAMA. 2000;284:2989–2990. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Outbreak of Rift Valley Fever in Yemen. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2000;49:1065–1066. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Fagbo SF. The evolving transmission pattern of Rift Valley fever in the Arabian Peninsula. Ann N Y Acad Sci. 2002;969:201–204. doi: 10.1111/j.1749-6632.2002.tb04378.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Zaki AM. Isolation of Flavivirus related to the tick-borne encephalitis complex from human cases in Saudi Arabia. Trans R Soc Trop Med Hyg. 1997;91:179–181. doi: 10.1016/s0035-9203(97)90215-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Memish Z, Balkhy HH, Francis C. Alkhumra haemorrhagic fever: case report and infection control details. Br J Biomed Sci. 2005;62:37–39. doi: 10.1080/09674845.2005.11978070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Charrel RN, Zaki AM, Attoui H. Complete coding sequence of the alkhumra virus, a tick-borne flavivirus causing severe hemorrhagic fever in humans in Saudi Arabia. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2001;287:455–461. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Madani TA. Alkhumra virus infection, a new viral hemorrhagic fever in Saudi Arabia. J Infect. 2005;51:91–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jinf.2004.11.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Outbreak of ebola hemorrhagic fever, Uganda, Aug 2000–Jan 2001. Can Communic Dis Rep. 2001;27:49–53. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Macdonald R. Ebola virus claims more lives in Uganda. BMJ. 2000;321:1037. doi: 10.1136/bmj.321.7268.1037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Wilder-Smith A, Freedman DO. Confronting the new challenge in travel medicine: SARS. J Travel Med. 2003;10:275–278. doi: 10.2310/7060.2003.2669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Vankatesh S, Memish Z. SARS: the new challenge to international health and travel medicine. Eastern Mediterranean Health Journal. 2004;10:655–662. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Madani TA. Preventive strategies to keep Saudi Arabia SARS-free. Am J Infect Control. 2004;32:120–121. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2003.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Memish Z, Wilder-Smith A. Global impact of severe acute respiratory syndrome: measures to prevent importation into Saudi Arabia. J Travel Med. 2004;11:127–129. doi: 10.2310/7060.2004.16954. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Global alert: Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome (SARS) Epidemiol Bull. 2003;24:1–5. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chotpitayasunondh T, Ungchusak K, Hanshaoworakul W. Human disease from influenza A (H5N1), Thailand, 2004. Emerg Infect Dis. 2005;11:201–209. doi: 10.3201/eid1102.041061. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Ku AS, Chan LT. The first case of H5N1 avian influenza infection in a human with complications of adult respiratory distress syndrome and Reye's syndrome. J Ped Child Health. 1999;35:207–209. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.1999.t01-1-00329.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Mounts AW, Kwong H, Izurieta HS. Case-control study of risk factors for avian influenza A (H5N1) disease, Hong Kong, 1997. J Infect Dis. 1999;180:505–508. doi: 10.1086/314903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Beigel JH, Farrar J, Han AM. Avian influenza A (H5N1) infection in humans. N Engl J Med. 2005;353:1374–1385. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra052211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Poliomyelitis outbreak escalates in the Sudan Wkly Epidemiol Rec. 2005;80:2–3. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Health statistics: Saudi Ministry of Health, 2005

- 83.Al-Harthi AS, Al-Harbi M. Accidental injuries during muslim pilgrimage. Saudi Med J. 2001;22:523–525. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Bener A, Jadaan KS. A perspective on road fatalities in Jeddah, Saudi Arabia. Accid Anal Prev. 1992;24:143–148. doi: 10.1016/0001-4575(92)90030-m. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Ansari S, Akhdar F, Mandoorah M, Moutaery K. Causes and effects of road traffic accidents in Saudi Arabia. Public Health. 2000;114(1):37–39. doi: 10.1038/sj.ph.1900610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Helbing D, Farkas I, Vicesk T. Simulating dynamical features of escape panic. Nature. 2000;470:487–490. doi: 10.1038/35035023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Bianchi RR. Guests of God: pilgrimage and politics in the islamic world. Oxford University Press; New York: 2004. pp. 7–21. [Google Scholar]

- 88.Australia EM. Safe and healthy mass gathering. In: Australia Emergency Management., editor. Australia Emergency Manuals series. Commonwealth of Australia; 1999. pp. 1–103. [Google Scholar]

- 89.Bouchama A, Knochel JP. Heat stroke. N Engl J Med. 2002;346:1978–1988. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra011089. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Merican MI. Management of heatstroke in Malaysian pilgrims in Saudi Arabia. Med J Malaysia. 1989;44:183–188. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Weiner JS, Khogali M. A physiological body-cooling unit for treatment of heat stroke. Lancet. 1980;1:507–509. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(80)92764-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Claire B. Sacred slaughter: the sacrificing of animals at the hajj and id-al-adha. J Cult Geog. 1987;7:67–88. [Google Scholar]

- 93.Rahman MM, Al-Zahrani S, Al-Qattan MM. “outbreak” of hand injuries during hajj festivities in Saudi Arabia. Ann Plast Surg. 1999;43:154–155. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]